Summary

Earlier age of drinking is a well-known predictor for a variety of adverse public health consequences in the United States and worldwide. In longitudinal research on early-onset drinkers, a great deal of attention has been paid to the identification of subgroups of individuals who follow similar sequential patterns of drinking behaviours. However, research on the sequential development of drinking behaviour can be challenging in part because it may not be possible to directly observe the particular drinking behaviour stage at a given point in time. To address this difficulty, one can use a latent class analysis (LCA) approach, which provides a set of principles for the systematic identification of homogeneous subgroups of individuals. We apply an LCA approach in an investigation of stage-sequential patterns of drinking behaviours among early-onset drinkers from early to late adolescence, using data from the ‘National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997.’ In this work, an identification procedure is used to sort different patterns of drinking behaviours into a small number of classes, based on responses to questions about drinking at each measurement occasion; with class assignment, next the class sequencing of early-onset drinkers over the entire set of time points is evaluated in order to identify two or more homogeneous subgroups. A condition to be satisfied is that all early-onset drinkers in a subgroup should exhibit a similar sequence of class memberships over time. This approach uncovers four common drinking behaviours in early-onset drinkers over three measurements from 1997 through 2003. The sequences of drinking behaviours can be grouped into three groups of sequential patterns representing the most probable progression of early-onset drinking behaviours.

Keywords: Early-onset drinker, Latent class analysis, Longitudinal data, Maximum likelihood, Stage-sequential process, Under-age drinking

1. Introduction

Alcohol is among the drugs most widely used by young people of ages between 12 and 20, in the United States (U.S.) and in many countries of the world (e.g., see Degenhardt et al. (2008)) For example, according to the recent Monitoring the Future study of school-attending youths in the U.S., the prevalence of drinking alcoholic beverages increased across age groups, from 32% among 8th graders (when most students are between 13 and 14 years old, depending on when the birthday occurs), to 53% among 10th graders (when most students are between 15 and 16 years old) and 66% among 12th graders (when most students are between 17 and 18 years old). In the survey, about 13% of 8th graders admitted getting drunk at least once during the year, and that number increased to 46% among 12th graders (Johnston et al., 2009). Among under-age drinkers 18–20 years old, more than 90% of the alcohol consumed is in the form of heavy episodic drinking (Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention, 2005), hereafter termed ‘binge’ drinking. Numerous studies have found that adolescent drinking may have profound individual and social consequences. Alcohol use in adolescence is associated with decreased learning and lower rates of school retention and graduation (Keeling, 2000), with violent and aggressive behaviours (White et al., 1999; Swahn et al., 2004), and with injuries and death caused by alcohol-related accidents (Hingson et al., 2005; Naimi et al., 2003). According to estimates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), each year during 2001–2005 heavy alcohol use resulted in an estimated 79–80 thousand deaths and 2.3 million years of potential life lost in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009).

According to the CDC 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 24% of high school students in the U.S. begin to drink alcohol before the age of 13. These very early onset drinkers are about three times more likely than their peers to consume five or more drinks on a regular basis (i.e., six times or more per month) by the time they are age 17 years old (e.g., see ‘binge’ drinking estimates from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Youth Online (2008)). Early-onset drinking is linked to a variety of other risky behaviours that have adverse health consequences. It seems that the earlier a youth begins to drink, the more likely it is that the youth will at some point experience alcohol dependence (Grant and Dawson, 1997; Hingson et al., 2006), have unintentional injuries (Hingson et al., 2000), drive after drinking (Lynskey et al., 2007; Zakrajseka and Shope, 2006), and engage in physical fights (Hingson et al., 2001).

The majority of prevention programs for under-age drinkers aim to find the time points or intervals in time that provide the best opportunities to slow the process of alcohol dependence or prevent the use of illegal drugs. Recently, prevention science is increasingly turning to the idea of stage-sequential process. A common theme of stage-sequential process is that, at any moment, individuals can be sorted into distinct qualitative stages, and they can change their stage membership over time. The idea of a stage-sequential process has motivated numerous studies on the initiation and progression of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among American youth (Chung et al., 2005; Collins et al., 1994; Kandel and Yamaguchi, 1993). In many familiar drug use and dependence studies, there are many dynamic variables that are best represented as a sequence of qualitative stages. For example, the acquisition of nicotine dependence is often depicted as a stage-sequential process that includes the initial trying of tobacco, experimentation and regular smoking before dependence (Flay, 1993; Leventhal and Cleary, 1980; Mayhew et al., 2000). The gateway theory, another example of a stage-sequential process, suggests that earlier experiences with alcohol or tobacco serve as a gateway through which many young people will pass before they first use illegal drugs (Chung and Martin, 2001; Collins, 2002; Guo et al., 2000; Kandel and Yamaguchi, 1993; Newcomb and Bentler, 1986). Knowledge regarding the stage-sequential process of early-onset drinking behaviours can inform prevention efforts because early-onset drinkers are at a higher risk of also becoming illegal drug users (Collins et al., 1994; Ellickson et al., 2003; Kandel and Yamaguchi, 1993; Yu and Williford, 1992). However, research on the stage-sequential development of early-onset drinking behaviours is challenging in part because there is no single widely accepted response variable for measuring youthful alcohol progressions over time. Furthermore, evidence suggests that the drinking behaviours of adolescents are different from those of their adult counterparts in terms of the diagnostic criteria originally developed for adult drinkers (Deas et al., 2000; Chung et al., 2002).

The latent class analysis (LCA) approach is perhaps the most straightforward mixture model now being used to identify mutually exclusive subgroups of individuals based on their responses to measured variables (called items). In LCA, associations among items are explained by positing the existence of one or more subgroups (i.e., classes) that are not observed directly (Clogg and Goodman, 1984; Goodman, 1974), and all the individual members in a latent subgroup are expected to have essentially the same responses to the items. In this paper, we use the LCA approach to identify subtypes of sequential patterns of alcohol use among early-onset drinkers on the basis of responses to alcohol-related items.

A number of methods for analyzing stage-sequential processes have been derived from the family of LCA by treating items as fallible indicators of unseen states that are subject to measurement error. These new methods include latent transition analysis (LTA) (Collins and Wugalter, 1992; Chung et al., 2008) and general growth mixture models (GGMM) (Muthén and Shedden, 1999; Muthén, 2004). In LTA, the measurement model at each point in time is specified with an LCA, and the stage-sequential development is summarized in terms of transition probabilities among latent classes over time. A transition across classes is typically represented with a first-order Markov chain, on the assumption that class membership at time t depends only on class membership at time t − 1. When there are data at three or more time points, however, it may be useful to check whether a small number of common patterns of the sequences of class membership can characterize the behaviour progression of most individuals. The GGMM approach allows one to identify such subgroups of individuals who share similar developmental trajectories of the behaviour observations on items over time. This modeling technique permits investigators to estimate latent trajectory classes and to examine their unique relations to covariates. The premise of the GGMM is that the patterns in the repeated behaviour observations reflect a small number of trajectories, each of which corresponds to a latent class identified by the initial level and trajectory shape of the observations on items over time. This method allows one to investigate common developmental patterns across multiple points in time, but it assumes that each subgroup has the same general underlying pattern of growth (e.g., linear or quadratic). The LCA approach has been used widely to identify patterns in the progression of adolescents’ use of various drugs, including alcohol (Lanza and Collins, 2006) and tobacco (Guo et al., 2009; Velicer et al., 2007), or to investigate patterns in the initiation and progression of drug-taking behaviours across a number of different drugs (Dierker et al., 2007).

In this study, we propose the use of latent class profile analysis (LCPA) to identify subtypes of sequential patterns of early-onset drinking behaviours, where the identification process is divided into two steps. In the first step, LCPA identifies discrete subgroups of early-onset drinkers who have similar drinking behaviours (manifest responses to items) at each measurement time. We will refer to the subgroups identified in this first step as classes. The class identification is done separately for each measurement occasion, but the meaning of underlying set of latent classes can be constrained to be invariant across time so as to aid interpretation of trend data. That is, the temporal stability of the meaning of latent class is necessary to assign a clear interpretation to trends in class prevalence and composition. For example, if the characteristics of Class 1 are allowed to vary over time, then the meaning of a statement such as ‘Membership in Class 1 increased from 40% among early adolescents to nearly 70% among mid adolescents’ becomes a dubious assertion, because Class 1 would be allowed to have very different meanings in early and mid adolescence. In the second step, we use LCPA to examine the early-onset drinkers’ class memberships over the entire set of time points in order to classify the population into two or more subgroups based on their class sequencing. We refer to the subgroups identified in the second step as class profiles or simply profiles. By applying an LCPA to the longitudinal study of early-onset adolescent drinking, all drinkers in a class at a certain point in time are expected to be homogeneous in terms of their drinking behaviours, and those individuals in a given class profile will have similar sequential patterns of class membership over time. We allow the probabilities for early-onset drinkers over the set of class profiles to be affected by covariates through a binary or polytomous logistic regression. As in classical logistic regression theory, the covariates are non-stochastic and are assumed to be known and fixed. We present a maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation of the LCPA using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977) implemented by the codes written in Intel(R) Visual Fortran 11.1 and R Version 2.11 (R Development Core Team, 2010).

We apply an LCPA to alcohol drinking behaviours as manifest in self-reported items drawn from the ‘National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997’ (NLSY97), a survey that explores the transition from school to work and from adolescence to adulthood in the United States (http://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsy97.htm). The NLSY97 was based on a sample of 8984 U.S. adolescents who were between the ages of 12 and 18 during the first survey in 1997. The sample considered in this study includes 4834 adolescents aged 12–14 as of 1997. Their drinking behaviours were tracked over the three survey waves in 1997 (Wave 1), 2000 (Wave 4), and 2003 (Wave 7), corresponding to early adolescence (ages 12–14), middle adolescence (ages 15–17), and late adolescence (ages 18–20), respectively. In the first survey year, 1997, adolescents were asked if they had ever drunk an alcoholic beverage (childhood sips were not included). The possible responses were binary (i.e., yes or no). Of the 4834 adolescents, 1416 answered “yes,” and they are identified as the early-onset drinkers who are of interest for this study. Note that the minimum legal drinking age in the United States is 21; the early-onset drinkers under study all had started to drink (more than a sip) by age 14 years, at least seven years before the legal drinking age.

2. Latent class profile analysis

2.1. Motivation

In an earlier study, standard LCA was used with repeated measures to identify common pathways through a stage-sequential process (Lanza and Collins, 2006). In that work, the authors studied patterns of heavy drinking in people between ages of 18 and 30 in order to investigate the relationship between college enrollment and the development of heavy drinking. The study used a binary indicator of heavy drinking at six different points in time, allowing a straightforward use of LCA to produce a set of classes, each of which was characterized by a particular sequence of responses to the item over time. This, however, was a special situation in which drinking behaviour was measured by just one item per time. In LCA models based on more than one survey item at each point in time, the interpretation of the results is much more complex. In particular, it is difficult to disentangle the substantive problem regarding the stage-sequential process of drinking behaviours because the resulting classes from the standard LCA contain information on two types of latent variables (i.e, the class and the class profile defined in Section 1) simultaneously. Although imposing restrictions on the parameters may allow for confirmatory tests concerning the stage-sequential process when using the standard LCA, it is difficult to impose plausible restrictions a priori in the absence of a well-established substantive theory.

As introduced in Section 1, latent class profile analysis (LCPA) is based on latent class theory, which posits that homogeneous subgroups of individuals (i.e., classes) can be identified by their responses to a set of measured items. At each measurement occasion, LCPA considers the joint distribution of items as a mixture of classes that are not directly observable. A fundamental issue in LCPA involves specifying the relationships among class memberships over multiple points in time in a flexible yet parsimonious way. Let Ct and cit denote, respectively, the latent class membership variable at time t and its observed value for the ith individual, with C nominal categories for t = 1, …, T. Here, the same set of C latent classes is postulated over time and the meaning of set of underlying classes can be invariant over time. If each individual’s class membership over time (i.e., cit) could be observed, we would like a joint model for class membership across T time points, , where all possible sequences of class membership can be re-expressed as frequencies in a contingency table with CT cells for n individuals. This table can produce a reasonable inference about the important aspects of the common progression of class membership over time. In ordinary LTA, the latent class variable at each occasion is linked by the marginal class prevalence at the initial time point and the following transition probabilities over two consecutive times (Collins and Wugalter, 1992; Chung et al., 2008). This mechanism allows individuals to move from one class to another under the assumption of a first-order Markov chain. It is also possible to incorporate a higher-order latent variable in order to investigate the stage-sequential process of class membership. For example, the “mover-stayer” model uses a second-order latent variable to identify two types of individuals—the movers and the stayers—based on their transition probabilities (Langeheine and van de Pol, 2002; Mooijaart, 1998). In the “mover-stayer” model, while restrictions on the transition probabilities are usually imposed for the stayers (e.g., the diagonal values are fixed to 1 in the matrix of transition probabilities), the transition probabilities for the stayers are estimated freely. Instead of considering the transition probabilities, LCPA identifies common pathways based on the joint frequencies of class membership over time. The details of the model and its underlying assumptions are described below.

2.2. Model

We define the categorical variable U to be the class profile membership, with possible values being S nominal categories, each representing one of the most common sequences of class membership that individual follows over time. The key feature of LCPA is that associations among class membership are assumed to arise over time because the population is composed of S different class profiles. However, an individual’s class membership—and therefore his or her class profile membership—is not directly observed; the class profile is a latent construct represented by a sequence of latent class memberships as in ordinary latent class theory.

Suppose we construct an LCPA model with C classes and S class profiles from a set of M items over T time periods. Let yit = (yi1t, …, yiMt)′ be a vector of discrete responses to M items given by the ith individual and used to measure latent class membership at time t, where each variable yimt can take values from 1 to rm for m = 1, …, M. Note that the items should be treated as categorical variable. If the ith individual’s sequence of class membership over time, c = (c1, …, cT), were observed, the joint probability that he or she belongs to the sequence c and the class profile s and provides responses yi = (yi1, …, yiT) (i.e., complete-data likelihood) would be

| (1) |

where I(y = k) is the usual indicator function which has the value 1 if y is equal to k and 0 otherwise. In (1), the following three sets of parameters are estimated:

ρmkt|ct = P(Ymt = k | Ct = ct) represents the probability of the response k to the mth item for a given class ct at time t;

represents the conditional probability of belonging to class ct at time t for a given class profile s; and

γs = P(U = s) represents the probability of belonging to the class profile s.

The ρ-parameter, which we call the primary measurement parameter, describes how individuals in each class tend to respond to the mth item at each occasion for m = 1, …, M. The primary measurement parameters can be constrained to be equal across occasions (i.e., ρmk1|c = ⋯ = ρmkT|c), so that the meaning of the classes is constrained over time. The η-parameter, which we refer to as the secondary measurement parameter, describes the relationship between a class ct at time t and a class profile s. An identified class profile can be interpreted via a set of estimated secondary measurement parameters as a specific individuals’ sequential pattern of class membership.

The marginal probability of item responses without regard for the latent variables (i.e., observed-data likelihood) is

| (2) |

The formulation of LCPA assumes the following: (a) the class profile membership U is related to the items (Y1, …, YT) only through the class membership (C1, …, CT); (b) the items Yt = (Y1t, …, YMt) are conditionally independent given a class membership ct at time t for t = 1, …, T; and (c) the class membership (C1, …, CT) is unrelated within a class profile s. The assumptions (b) and (c), called local independence by Lazarsfeld and Henry (1968), are the properties of LCPA that allow us to draw inferences about the unseen class and class profile variables. Note that the assumption (c) is required because the LCPA uses a joint model for class membership across T time points to classify latent-profiles. This assumption can be relaxed to some extent in the “mover-stayer” model, where changes in the class membership are identified by the second-order latent variable based on the transition probability. As with LTA, however, the “mover-stayer” model assumes that the class membership at time t depends only on class membership at time t − 1, given a second-order latent variable. The marginal prevalence of class membership at time t is not directly estimated in (2) but rather is a function of other parameters:

2.3. Latent class profile analysis with logistic regression

We now turn to an investigation of factors that might influence the sequential patterns of drinking behaviour among early-onset drinkers. A natural way to extend LCPA is to include factors suspected of playing a causal role in the drinking sequence and to investigate the relationship of these factors with the class profile membership. However, allowing primary or secondary measurement parameters to depend on covariates can be problematic. For example, if the secondary measurement parameters (i.e., η-parameters) are allowed to covary with covariates, those covariates may introduce associations between classes within a class profile, violating the local independence assumption. In such a model, the latent structure of a class profile might change as covariates are added or deleted; in some LCA software packages (e.g., LatentGold), covariates that are allowed to influence the latent structure are referred to as “active,” and covariates that are not allowed to influence the latent structure are referred to as “passive.” Then the composition of a class profile is no longer constant over the population, and the meaning of γs becomes unclear. Similar arguments can be applied to the primary measurement parameters (i.e., ρ-parameters). Thus we incorporate subject-specific covariates, allowing them to influence the class profile prevalence γs through a logistic regression, but measurement parameters are not allowed to vary along with these now “passive” covariates. Let xi = (xi1, …, xip)′ be a subject-specific p × 1 vector of covariates, either discrete or continuous. Then our model is

| (3) |

The probability of individual i being a member of class profile s is specified by the logistic link function,

| (4) |

where the coefficient vector βs = (β1s, …, βps)′ can be interpreted as the change in the log odds of belonging to a class profile s versus belonging to the referent class profile S (i.e., βS = 0) associated with a unit increase in the covariate. The first covariate will be a constant (i.e., xi1 = 1 for i = 1, …, n) to represent the intercept in the linear predictor; in this case, the model with p = 1 reduces to an LCPA without any covariates, as given in (2).

3. Parameter estimation and model diagnosis

3.1. EM algorithm

We use the EM algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977) to obtain ML estimates of the model parameters specified in (3). The E-step computes the conditional probability that an individual i belongs to the class profile s and the class sequence c = (c1, …, cT), given a set of item responses yi = (yi1, …, yiT) and covariates xi. The M-step maximizes the expected complete-data likelihood with respect to the model parameters. We can easily extend the EM algorithm to a model with missing observations on measurement items by using the missing at random (MAR) assumption (Rubin, 1987). Asymptotic standard errors for the estimated parameters can be calculated by inverting the negative Hessian matrix of the observed-data log-likelihood function upon convergence. The EM algorithm and the elements of the Hessian matrix of log-likelihood are detailed in the Appendix.

3.2. Model diagnosis and local identifiability

As with other statistical models, it is important to assess a latent class or profile model adequately at the outset since the model’s characteristics and performance have important ramifications for the analyses performed with the model. Selecting a model that does not adequately reflect the underlying latent structure can lead to incorrect inferences. If statistical criteria based solely on goodness-of-fit tests are used by themselves, the result is often to select models that are not substantively meaningful. Hence, the model should be chosen to capture the distinctive features of the data in as a parsimonious fashion, using a balanced judgment that takes into account both substantive knowledge and the objective measures available for assessing model fit.

The log-likelihood ratio statistic (LRT) is the standard way to assess goodness-of-fit; one compares the predicted response pattern frequencies with the observed frequencies appearing in the data. The asymptotic assumption for LRT generally does not hold because LCPA tends to involve large contingency tables with many degrees of freedom. In order to avoid giving up on the idea of an overall LRT test for goodness-of-fit, some have suggested alternatives in a mixture model (Rubin and Stern, 1994; Garrett and Zeger, 2000; Lo et al., 2001). For our example, we generated bootstrap samples of an LRT from the estimated LCPA model in order to determine the distribution of the LRT empirically (Langeheine et al., 1996). Bootstrap samples for an LRT that does not rely on any known distribution can be constructed in the following way: (a) Fit the LCPA model to the data set and obtain the observed LRT based on ML estimates; (b) draw a hypothetical new data set from the ML estimates; (c) fit the model to the simulated data set using the EM algorithm; and (d) compute the LRT based on output from (c). Repeating (b)–(d) many times (200 repetitions were used in our example) produces a bootstrap sample of the LRT. The area to the right of the observed LRT can be regarded as a bootstrap p-value.

When the data contain missing values, the LRT must be interpreted carefully. As noted by Little and Rubin (2002, Chap. 13), goodness-of-fit statistics are aggregated over the cross-classified contingency tables for all missingness patterns appearing in the data set. Models that fit well may have large values of LRT with missing values because LRT also detects departures from the (usually implausible) hypothesis of missing completely at random. To overcome this difficulty in our example, we adjust each LRT by removing the portion corresponding to the saturated model with missing data. Details of this adjustment are described by Schafer (1997, Sec. 8.5.2). The bootstrapping procedure should be slightly modified as well in order to adjust LRT for the bootstrap sample with missing data: In the generated data set, the missing values are assigned to the location where missing occurs in the original data set.

In our example, in order to avoid local maxima, we used 100 different sets of starting values and selected the solution with the best fit, which corresponded to the highest likelihood value. When we generated the bootstrap samples of an LRT, however, we used the ML solution (after applying the 100 different sets of starting values) as a set of starting values for each generated data set in step (b) because of the intensive computation necessary.

It is also important to examine the relative model fit versus models that are plausible. Relative model fit evaluates how well a model fits compared to another competing model. Measures that are based on information criteria such as AIC (Akaike, 1987) and BIC (Raftery, 1995; Schwarz, 1978) can provide appropriate decision rules when comparing models that have been estimated by likelihood-based methods. Although it is known to be asymptotically inconsistent, AIC is preferred over BIC in those cases where the model is complex with a relatively large number of parameters, which is the situation we encounter in this work (Lin and Dayton, 1997).

Model identification is required to estimate the parameters of an LCPA model correctly. A necessary but not sufficient condition for achieving model identification is that the number of parameters is smaller than the number of possible item-response patterns. For example, in the case of three binary items at three times, the number of possible response patterns is 29 = 512. Therefore, as many as 511 parameters can potentially be estimated in the model. However, it is impossible to say a priori whether or not this model is indeed identifiable. As discussed by McHugh (1956) and Goodman (1974), a singular Hessian matrix—or, equivalently, a Hessian matrix with negative eigenvalues—indicates the model is not locally identifiable for the given data. If the observed data log-likelihood is concave, the inverse of (−1 times) Hessian matrix of this log-likelihood will consistently estimate the covariance matrix for the ML estimates. A covariance matrix with “large” variances can indicate problems with model identifiability. In many cases, however, the Hessian-based variances are often questionable because the log-likelihood is not concave. For example, if any of the estimated measurement parameters is close to zero or to one—which is favorable from the measurement perspective—then we cannot estimate variances. In situations where some estimated parameters lie on the boundary, those values can be fixed to zero or one a posteriori in order to make the remaining parameters identifiable (Formann, 2003).

Although the derivatives are not difficult to calculate, the Hessian matrix for LCPA with covariates may have an unreasonably large dimensional structure. The LCPA model has an appealing marginalization property: Averaging over an arbitrary distribution for the covariates xi produces a marginal LCPA with identical values of measurement parameters (Bandeen-Roche et al., 1997). This marginalization property implies that the local identifiability of a logistic LCPA model can be assessed in two steps. In the first step, we check whether the marginal model is locally identifiable using the Hessian matrix of the LCPA model without covariates. In the second step, we evaluate the following two conditions: (1) the design matrix (x1, …, xn)′ should have full column rank; and (2) γs(xi) should not be zero for all s = 1, …, S for at least one individual. Bandeen-Roche et al. (1997) provide additional details on this marginalization property.

4. An analysis of ‘National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97)’ data

4.1. Data

As explained in the closing paragraph of Section 1, all drinkers under study are qualified as early-onset drinkers. To measure drinking behaviours in these early-onset drinkers we focused on three self-report items: The participants were asked (a) how many days they had had one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage during the last 30 days (Recent Drinking); (b) how many days they had had five or more drinks on the same occasion during the past 30 days (‘Binge’ Drinking); and (c) how many days they had had drinks right before or during school or work hours in the last 30 days (Drinking at School). The responses for Recent Drinking, ranging from 0 to 30 days, were reduced to a three-category indicator, and the recent drinking involvement of the participants was characterized as non-drinker (0 days of drinking), occasional drinker (1–5 days of drinking), or regular drinker (6 or more days of drinking). We chose to classify regular drinkers in this way because, on average, under-age drinkers in the United States drink five days per month (U.S. Department of Health Human Services, 2009). For diagnostic purpose, heavy episodic (binge) drinking often has been defined in relation to as four or more drinks in a row for women and five or more drinks in a row for men (Wechsler et al., 1994, 1995). A gender-specific measure of binge drinking was not available in NLSY97 and the use of different specifications for girls and boys creates some added complexity in the study of drinking behaviours. For these reasons, in this study, binge drinking refers to the same drinking experiences for male and female early-onset drinkers. For (b) Binge Drinking, respondents who had consumed five or more drinks on the same occasion at least one time in the last 30 days were characterized as binge drinkers. A binary indicator was also created for (c) Drinking at School. Respondents who had consumed alcoholic beverage right before or during school or work hours at least once in the last 30 days were placed into a Drinking at School group, while respondents without such drinking were put into a second, non-school-drinking group.

Using these three items (a)–(c) along with sex and race, we investigate the progression of early-onset drinking behaviours during adolescence by addressing such questions as (1) what kinds of classes can be identified as common drinking behaviours; (2) what is the prevalence of the various class memberships at each time point; (3) what kinds of class profiles can characterize the progression of drinking behaviours; (4) what is the prevalence of the identified class profiles; and (5) how strongly are potentially explanatory factors related to the sequential patterns of drinking behaviours. Of the 1416 early-onset drinkers, 1407 had completed data for the covariates, and we analyzed this sample of 1407 for the study. The percentage of participants missing a response to an item at ages 12–14, 15–17, and 18–20 was 0.1%, 8.2%, and 12.4%, respectively. Attrition clearly played a role in the drop-off, as the data were from 3- and 6-year follow-ups, but we speculate that the substantial increases in the amount of missing data at ages 15–17 and 18–20 were also due to sample selection effects: The early-onset drinkers may have been less likely than their counterparts who had not started drinking early to return for the subsequent surveys.

4.2. Model selection

The first and most crucial step in LCPA is to choose an appropriate number of classes and class profiles. As shown in the work of Bandeen-Roche et al. (1997), the marginalization property implies that we do not need to consider covariates when selecting the number of classes and class profiles. To keep the meaning and interpretability of classes stable over time, as previously discussed, we fitted LCPA models in which the primary measurement parameters were constrained to be equal over time. We began by fitting a series of two-class LCPA models where the pathways of the class membership were mapped onto between two and four profiles. Then we increased the number of classes and fitted three-class LCPAs with different number of profiles. This procedure was repeated until we reached a model with six classes and six profiles. Table 1 shows a series of LCPA models with evaluations based on the bootstrap p-value for goodness of fit and AIC.

Table 1.

Goodness-of-fit statistics for a series of LCPA models under the different number of classes and profiles

| Number of classes |

Number of profiles |

Number of parameters |

LRT | Bootstrap p-value |

AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | 15 | 812.81 | 0.000 | 12103 |

| 3 | 19 | 812.81 | 0.000 | 12111 | |

| 4 | 23 | 812.81 | 0.000 | 12119 | |

| 3 | 2 | 25 | 492.84 | 0.000 | 11803 |

| 3 | 32 | 452.99 | 0.025 | 11777 | |

| 4 | 39 | 447.16 | 0.015 | 11785 | |

| 5 | 46 | 445.64 | 0.020 | 11798 | |

| 4 | 2 | 35 | 449.80 | 0.005 | 11780 |

| 3 | 45 | 404.58 | 0.305 | 11755 | |

| 4 | 55 | 392.61 | 0.440 | 11763 | |

| 5 | 65 | 387.90 | 0.315 | 11778 | |

| 5 | 2 | 45 | 429.69 | 0.025 | 11780 |

| 3 | 58 | 375.52 | 0.375 | 11752 | |

| 4 | 71 | 357.65 | 0.585 | 11760 | |

| 5 | 84 | 347.64 | 0.595 | 11776 | |

| 6 | 2 | 55 | 421.65 | 0.015 | 11792 |

| 3 | 71 | 367.31 | 0.410 | 11770 | |

| 4 | 87 | 338.81 | 0.735 | 11773 | |

| 5 | 103 | 325.88 | 0.810 | 11792 | |

| 6 | 119 | 306.07 | 0.795 | 11804 | |

The AIC value of the five-class/three-profile LCPA (11752) was the smallest such value, and its bootstrap p-value also indicated adequate fit (0.375). As we discussed above, in the absence of strong prior beliefs, the number of classes should be chosen to strike a balance among parsimony, fit, and interpretability. Although the five-class/three-profile LCPA provided the smallest AIC value, this empirically superior model may not be substantively meaningful. Furthermore, the bootstrap p-value suggested that the data were adequately fitted under the more parsimonious model with a four-class structure. By contrast, all three-class LCPAs failed to show evidence for a good fit. Thus we focused on only the four- and five-class LCPA models and evaluated them by comparing the primary measurement parameters in order to select the number of classes.

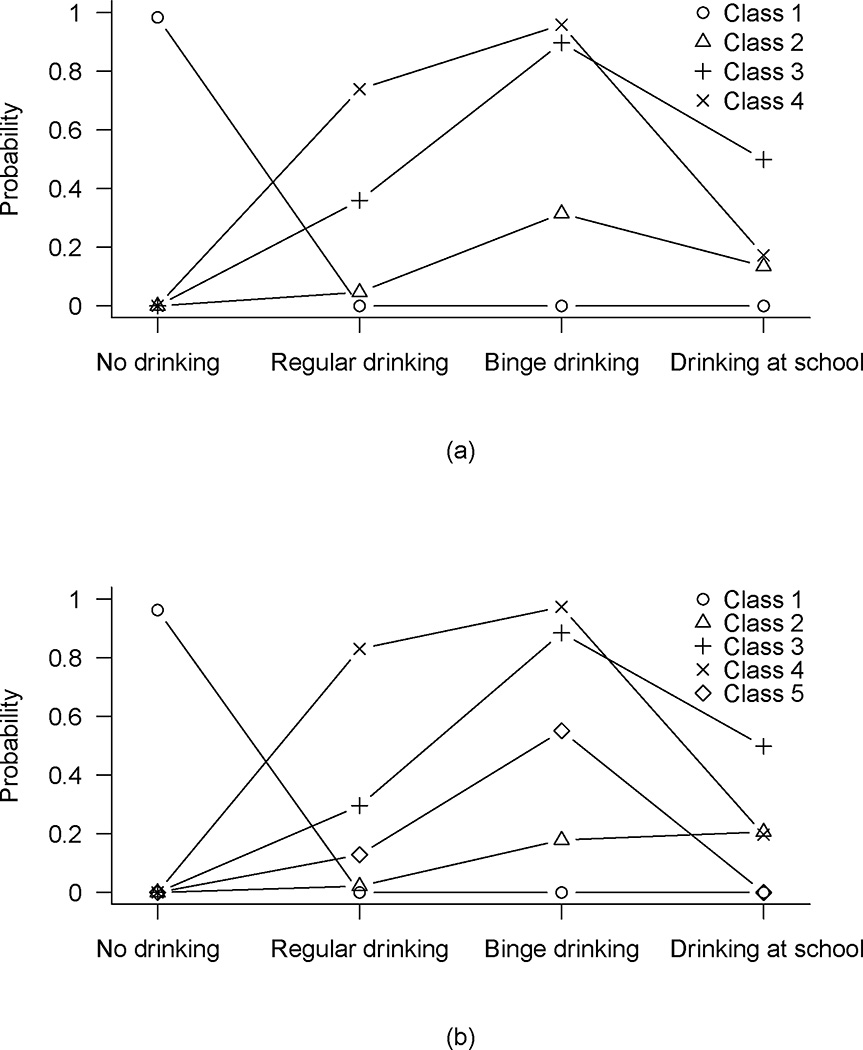

Plots of the estimated primary measurement parameters under the four-class and the five-class models are shown in Fig. 1. We selected the four-class/three-profile LCPA model and the five-class/three-profile LCPA model based on AIC, bootstrap p-value and the principle of parsimony. Exploring LCPA models with different numbers of profiles, we also found that the estimated primary measurement parameters were invariant across models with different number of profiles. In Fig. 1, the first and second points in the x-axis, “no drinking” and “regular drinking,” represent the categories of “no drinking in the last 30 days” and “drinking six or more days in the last 30 days” in the Recent Drinking item, respectively. As can be seen in Fig. 1(a), individuals in Class 1 have a high probability of “no drinking,” those in Class 2 have low probabilities for all items, those in Class 3 have higher probabilities of “binge drinking” and “drinking at school,” and those in Class 4 have higher probabilities for “regular drinking” and “binge drinking,” but a lower probability of “drinking at school” compared to those in Class 3. As shown in Fig. 1(b), an extra class (Class 5) appears under the five-class LCPA model. The item profile of this Class 5 is similar to the item profile of Class 3, and the estimated values of the primary measurement parameters for Class 5 are similar to those values for Class 2. The interpretation of the classes derives from their ordering with respect to primary measurement parameters. The substantive meaning of Class 5, however, is not clearly differentiated from the meanings of Class 2 and Class 3. Thus it is not clear that the five-class model offers additional insight when compared with the four-class model.

Fig. 1.

Estimated response probabilities for the drinking behaviours within each class (i.e., primary measurement parameters) under (a) the four-class/three-profile LCPA and (b) the five-class/three-profile model, where the primary measurement parameters have been constrained to be constant over time

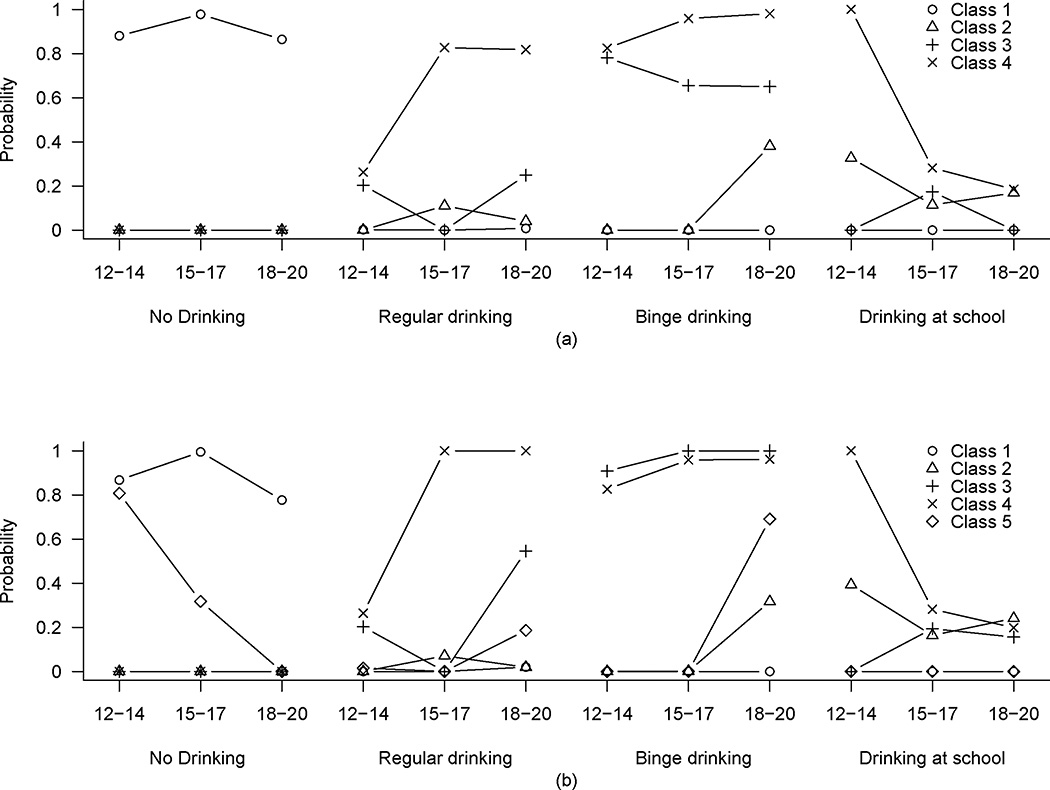

Furthermore, the primary measurement parameters of the four-class LCPA are more stable over time than those of the five-class model. Although primary measurement parameters can be constrained to be constant over time, if we allow them to vary, the amount that these parameters change over time may be evidence for the superiority of one model to the other. As explained in the Introduction section, if the primary measurement parameters fluctuate strongly over time, then it is difficult to assign a clear interpretation to classes and class profiles, because the interpretation of a class is derived from its ordering with respect to the primary measurement parameters. For example, the meaning of “the group of early-onset drinkers who remain in Class 5 over time” can be difficult to interpret if Class 5 has very different meanings in each survey year. Plots of the estimated primary measurement parameters for each item are shown for the unconstrained four- and five-class models in Fig. 2. The large fluctuations in “no-drinking” and “binge drinking” for Class 5 are the most troubling aspect of five-class model. Note that Class 5 is the extra class that appears when moving from the four-class model to the five-class model. Although we do see some increasing and decreasing trends in some classes for the items “regular drinking” and “drinking at school,” the overall picture that emerges from Fig. 2(a) is that the four-class LCPA is better behaved than the alternative five-class structure.

Fig. 2.

Estimated response probabilities for the drinking behaviours within each class (i.e., primary measurement parameters) under (a) the four-class/three-class profile LCPA and (b) the five-class/three-class profile LCPA, where the primary measurement parameters have been freely estimated over time

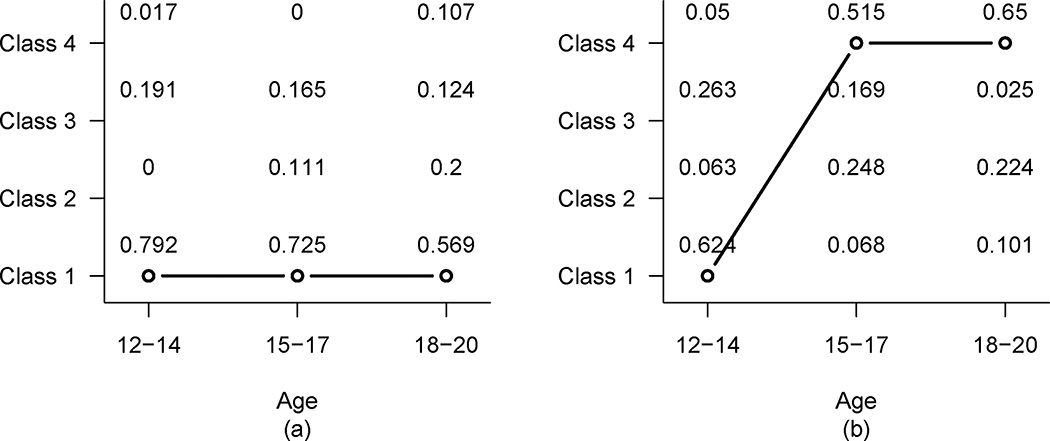

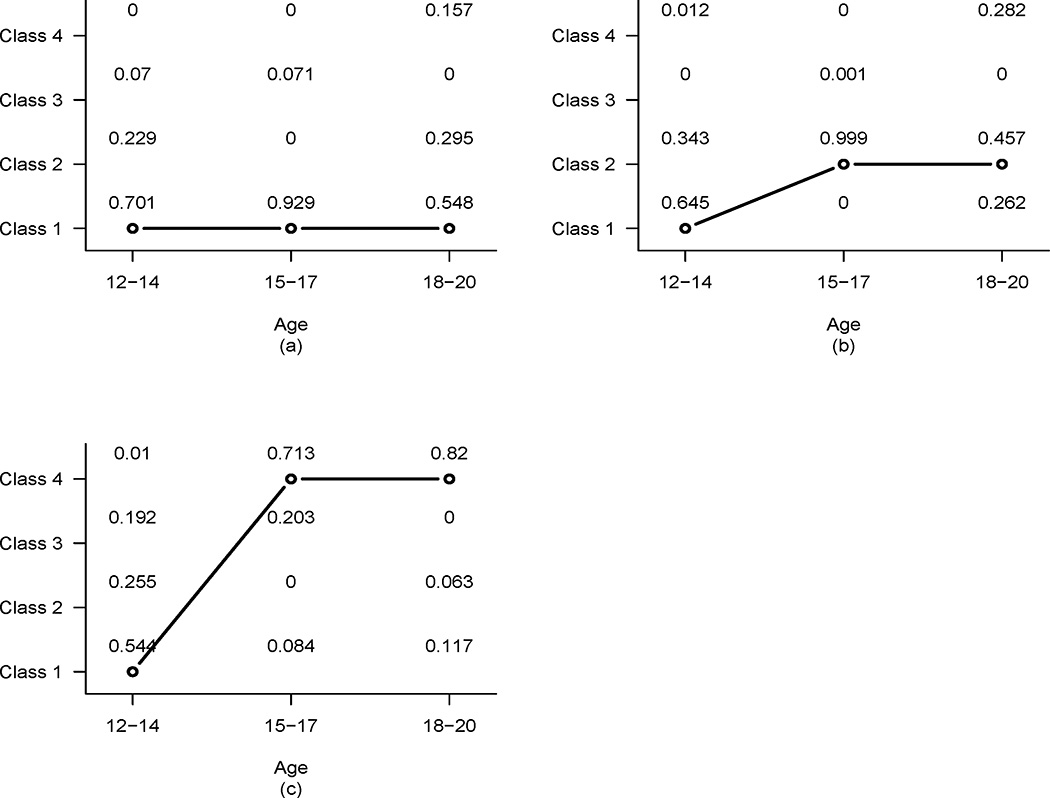

To select the optimum number of profiles, we studied a number of four-class LCPA models with differing numbers of profiles. As shown in Table 1, among the various four-class models, it was the model with three profiles that had the smallest AIC value. Therefore, we evaluated the more parsimonious four-class/two-profile LCPA by comparing its secondary measurement parameters with those under the four-class/three-profile LCPA. Fig. 3 shows the two sequential patterns of class membership along with their estimated secondary measurement parameters under the four-class/two-profile model; members in Profile 1 were Class 1 stayers, and Profile 2 contained early-onset drinkers who advanced over time from Class 1 to Class 4. In this figure, a straight line from one age group to another connects the largest value of the estimated secondary measurement parameters at each age group. Fig. 4 shows the results of moving to three profiles. The extra class profile consists of early-onset drinkers who advanced over time to Class 2, as shown in Fig. 4(b); this profile accounts for a rather large proportion of the sample (28.6%). The two-profile LCPA ignored this quite common sequential pattern, which has substantive meaning concerning the transition into recent drinking behaviour. Since the three-profile model provides a more distinct classification of sequential patterns of class membership and exhibits an empirical superiority to the two-profile LCPA based on goodness-of-fit statistics, we selected the four-class LCPA with three profiles.

Fig. 3.

Estimated probabilities of belonging to a specific class at a certain time point (i.e., secondary measurement parameters) for (a) Profile 1 and (b) Profile 2 under the four-class/two-profile LCPA model

Fig. 4.

Estimated probabilities of belonging to a specific class at a certain time point (i.e., secondary measurement parameters) for (a) Profile 1, (b) Profile 2, and (c) Profile 3 under the four-class/three-profile LCPA model

To investigate local identifiability for the selected model, we fixed some parameters in order to make the remaining parameters identifiable, as proposed by Formann (2003). Under the four-class/three-profile LCPA, the EM algorithm reached the final solution with 17 boundary estimates. The estimates of 6 primary and 11 secondary measurement parameters were less than 0.001. Hence, we set those parameters to zero a posteriori, reducing the number of parameters to be estimated to 28. The Hessian matrix in the ML solution was non-singular under this condition, and the maximum value of the Hessian-based variances was 0.016. Therefore, we concluded that the four-class/three-profile model under consideration was locally identifiable. Finally, we added sex (male/female) and race (white/black/hispanic/other) as covariates in order to investigate variations in the relative occurrence of class profile membership.

4.3. Parameter estimates

The estimated primary measurement parameters are presented in Table 2. For each given class, the two values under the “recent drinking” column provide the probabilities of having reported no drinking (0 days of drinking in the last 30 days) and regular drinking (6 or more days of drinking in the last 30 days). The other two columns show the probabilities of having reported “binge drinking” (five or more drinks at one time) and “drinking at school” (drinking right before or during school or work hours). Values close to zero or to one indicate a good measurement of the latent class. An inspection of the values in Table 2 indicates that these items are relatively good measures for a four-class LCPA model and that the estimated values together provide a meaningful interpretation for each class. Thus we propose that a useful group of classes consists of the “not current drinkers,” who have not been involved in any drinking in the previous 30 days; “light drinkers,” who drink but have no history of binge drinking or drinking at work or school; “occasional binge drinkers,” who take part in irregular binge drinking but do nor drink regularly; and “regular binge drinkers,” who both drink regularly and engage in binge drinking.

Table 2.

Estimated response probabilities to the drinking items for each class (i.e., primary measurement parameters) under the four-class/three-profile LCPA with logistic regression

| Class | Drinking items | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent drinking | Binge drinking |

Drinking at school |

||

| non-use | regular | |||

| Not current drinkers | 0.896 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Light drinkers | 0.000 | 0.074 | 0.341 | 0.110 |

| Occasional binge drinkers | 0.000 | 0.138 | 0.614 | 0.386 |

| Regular binge drinkers | 0.000 | 0.717 | 0.969 | 0.197 |

Although our selected LCPA imposes equality constraints on the primary measurement parameters, the class prevalence estimates vary freely by age group. Table 3 presents the estimated marginal probability of an early-onset drinker belonging to a particular class at each of the age groups. From this table, we can see that the prevalence of “not current drinkers” decreased from 0.712 among adolescents who were ages 12–14 in 1997 to 0.387 by the time they were 18–20 because of growth in the classes of “light drinkers” and “regular binge drinkers.” Interestingly, the prevalence of binge drinkers, as seen in the combined membership of “occasional binge drinkers” and “regular binge drinkers”, increased from 0.196 among adolescents who were ages 12–14 to 0.354 by the time they were 15–17; the prevalence then was levelled off at 0.372 by the time they were 18–20. The class of “occasional binge drinkers” disappeared, however, by the time the early-onset drinkers had reached late adolescence. This suggests that, among early-onset drinkers in the U.S., all binge drinkers who took part in irregular drinking when they were ages 15–17 advanced to the regular binge drinkers by the time they were ages 18–20. Early alcohol use may be associated with this particular pathway of binge drinkers, but our estimates are based only on a sample of early-onset drinkers; hence the extent to which the prevalence estimates based on this sample would generalize to adolescents who were ages 18–20 in the U.S. is unknown (Clearly, among later-onset drinkers in the U.S., there are some who engage in occasional binge drinking between age 18 and age 20, as in Wechsler et al. (1994)).

Table 3.

Estimated class prevalence proportions by age group under the four-class/three-profile LCPA with logistic regression

| Class | Age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 12–14 | 15–17 | 18–20 | |

| No current drinkers | 0.712 | 0.484 | 0.387 |

| Light drinkers | 0.093 | 0.162 | 0.241 |

| Occasional binge drinkers | 0.177 | 0.140 | 0.000 |

| Regular binge drinkers | 0.019 | 0.214 | 0.372 |

The secondary measurement parameters—that is, the conditional probabilities of class membership at each age group for a particular class profile—identify common sequential patterns of drinking behaviours. As shown in Table 4, among “non-drinking stayers” the probabilities of belonging to the class of “not current drinkers” are consistently higher than the probabilities of belonging to other classes (see the first row in Table 4), implying that early-onset adolescents in this profile are likely to remain as “not current drinkers” over time. The LCPA identified another two profiles of early-onset drinkers who tended to intensify their drinking habits over time. About 63.8% of adolescents aged 12–14 in the profile of “light drinking advancers” belonged to “not current drinkers” in 1997, but all of them advanced to “light drinkers” in 2000 (100%). By 2003, when they were 18 to 20, some of them had advanced even further to become “regular binge drinkers” (22.8%), although many others remained “light drinkers” (64.3%). The profile of “regular binge advancers” consists of early-onset adolescents who moved toward the “regular binge drinkers” class in their middle adolescence (55.4%) and stayed in that class in their late adolescence (82.7%).

Table 4.

Estimated probabilities of belonging to a specific class at a certain time point for each profile (i.e., secondary measurement parameters) and estimated profile prevalence under the four-class/three-profile LCPA with logistic regression

| Profile | Class | Age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12–14 | 15–17 | 18–20 | ||

| Non-drinking stayers (45.2%) |

Not current drinkers | 0.774 | 0.836 | 0.694 |

| Light drinkers | 0.068 | 0.000 | 0.271 | |

| Occasional binge drinkers | 0.158 | 0.164 | 0.000 | |

| Regular binge drinkers | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.035 | |

| Light drinking advancers (16.2%) |

Not current drinkers | 0.638 | 0.000 | 0.128 |

| Light drinkers | 0.343 | 1.000 | 0.643 | |

| Occasional binge drinkers | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Regular binge drinkers | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.228 | |

| Regular binge advancers (38.6%) |

Not current drinkers | 0.670 | 0.275 | 0.136 |

| Light drinkers | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.037 | |

| Occasional binge drinkers | 0.273 | 0.172 | 0.000 | |

| Regular binge drinkers | 0.041 | 0.554 | 0.827 | |

The most common profile is “non-drinking stayers” (46.9%), but 53.1% of the early-onset adolescents advance toward more higher levels of drinking, with 17.5% belonging to the profile of “light drinking advancers” and 35.6% being “regular binge advancers.” The estimated prevalences for the class profiles given in Table 4 were generated from a model that included the covariates. To obtain the prevalence estimates, we computed an average of the ML estimates for the subject-specific class profile probabilities over the entire sample,

Table 5 provides the estimated odds ratios and log-likelihood ratio-based significance levels for the regression coefficients. All covariates are significantly related with class profile membership at a 0.05 level based on the log-likelihood ratio statistic. The demographic factors tended to be related to class profile membership in the directions that we would expect. Speaking broadly, whites and males were more likely than their counterparts to belong to the profiles characterized by intensified drinking habits over time. As described in Subsection 3.1, the confidence intervals calculated by Hessian-based standard errors are given in Table 5. Both sex (being female) and race (being black) were associated with the likelihood of belonging to a particular profile versus the baseline profile (i.e., the profile of “non-drinking stayers”). By contrast, the demographic factor “hispanic” and “other race” did not have much of an association on the likelihood of belonging to the profiles characterized by intensified drinking habits over time.

Table 5.

Estimated odds ratios for the profiles and their 95% confidence intervals under the four-class/three-profile LCPA model (The profile of “non-drinking stayers” is the baseline)

| Covariate | Class profile | d.f. | Chi-square | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light drinking advancers |

Regular binge advancers |

||||

| Sex versus Male | |||||

| Female | 2.855 [1.301, 6.263] | 0.447 [0.305, 0.654] | 2 | 44.754 | < 0.001 |

| Race versus White | |||||

| Black | 0.275 [0.127, 0.597] | 0.191 [0.107, 0.339] | 6 | 71.784 | < 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.276 [0.060, 1.277] | 0.723 [0.422, 1.237] | |||

| Other race | 0.492 [0.129, 1.883] | 0.573 [0.251, 1.310] | |||

5. Discussion

This research has applied the LCPA for studying individuals’ sequential memberships in latent classes over time. LCPA examines the structure of individuals’ item responses and forms discrete classes in terms of their item response patterns. LCPA then examines individuals’ class memberships over the entire set of time points in order to sort out subgroups representing similar sequential patterns of class membership. We implemented the ML algorithm to estimate the unknown parameters via EM iterations. The results of our simulations (not shown here) suggested that this approach had good finite sample properties, especially in the situation where measurement parameters are strong (i.e., little bias in the parameter estimates, small root mean squared error and close to 95% coverage). For the models with weaker measurement parameters, however, increased sample size or an increased number of items, or both, were required to obtain consistent and efficient parameter estimates.

As an alternative to this ML estimation, Bayesian inference via Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) may be an attractive method of fitting an LCPA model. Bayesian methods open up new possibilities for model checking and fit assessment via the posterior check distribution, and they provide interval estimates without difficulty when hypothesis tests involving combinations of parameters are necessary to address specific research questions. However, new challenges, such as the label switching problem and subjectivity of the priors may emerge. With MCMC, the labeling problem causes dubious interpretation of long-run average of the output stream because the class labels may permute during the simulation run. This label switching phenomenon is evident in many applications, particularly with smaller samples, requiring an intelligent strategy for summarizing and interpreting the output stream. Recently, Chung et al. (2008) showed that the use of a data-dependent prior could reduce label switching in the Bayesian analysis for latent transition models by pre-classifying one or more individuals. They developed an automated dynamic algorithm to select individuals for pre-classification in latent transition models, and this method may be easily applicable to the LCPA model. In future work, we hope to explore the Bayesian approach for LCPA models. We expect that the ML and Bayesian approaches will display different strengths and weaknesses under different conditions.

LCPA is limited by the local independence assumption. Although the local independence assumption is the feature of LCPA that allows one to draw inferences about the latent variables, violations of this assumption may occur in many applications. When C classes exist, for example, violation of local independence can create the illusion that there are actually C + 1 (or more) classes, and C-class independent LCPA may provide poor fit. In our example, one of the five-class LCPAs provided the smallest AIC value, but the interpretation of the classes in this five-class structure was not substantively clear. This suggests that the four-class structure may be able to achieve empirical superiority when we accommodate local dependence under the four-class LCPA model. Under the traditional latent class model, local dependence can be formulated using a log-linear model (Espeland and Handelman, 1989) or a marginal model (Yang and Becker, 1997). Recently, Reboussin et al. (2008) proposed a locally dependent latent class model that used a pairwise odds ratio to quantify the local dependence between items. Although modeling the local dependence is beyond the scope of this study, strategies would be required to diagnose the adequacy of the local independence assumption for LCPA.

In our analysis using the NLSY97 data, we were able to identify plausible latent classes from items related to early-onset drinking behaviours. In addition, the LCPA model classified early-onset drinkers into subgroups of individuals who shared a similar progression in drinking behaviour during their adolescence. We estimated the effects of sex and race on the class profiles of sequential drinking patterns that had been identified. We offered supporting evidence for this latent structure not only by providing quantitative measures, but by noting the straightforward substantive interpretability of the structure. Several of the more important limitations of this data should be mentioned. For example, as noted in prior work (Anthony et al., 1999), there is a reliance upon self-report assessment in almost all longitudinal research on under-age drinking and other drug use, and that is true in this study as well. In theory, there are more valid alternatives to self-report assessment, such as toxicological assays to detect recent drinking, but in practice this approach has never been applied to large-sample longitudinal research with nationally representative samples such as NLSY97, mainly because of cost and logistical difficulties. Nonetheless, comparisons of self-reports about drinking with toxicological analyses indicate that evidence from anonymous and confidential population survey contexts is generally reliable. A more subtle limitation in self-report data from longitudinal studies involves a possible reactivity associated with repeated assessments, especially when the reassessments are made by the same survey staff members revisiting the participants over time; in this case the staff members may develop a social relationship with the participants that might induce socially desirable response that would not be present if different staff members were to make the assessments on successive occasions. Issues of this type have been reviewed more thoroughly by Anthony and colleagues (Anthony et al., 1999), among others. Fortunately, in this study, it was unusual for the same participant to be reassessed by the same staff member, and the self-report assessment method was designed to limit this source of measurement error. Another concern for self-report is that socially desirable responding regarding alcohol use may well change with maturation across adolescence. Specifically, self-report of younger adolescents (12–14 years old) regarding alcohol use could bias the results because they are probably less likely to admit to drinking as it is seen in the society as particularly “bad” in that age category. The social desirability bias is probably diminished by the time adolescents are 18–20 years old, as it is generally more culturally accepted to drink at this age and these same individuals may be more likely to be honest about their drinking.

The evidence used in this study was based upon longitudinal research about early-onset drinking behaviours, but researchers face the general issue of stage-sequential processes when dealing with many topics other than drinking, such as research on drug use (e.g., sequences from marijuana/cannabis to cocaine). The LCPA approach may also have applicability in longitudinal studies of the epidemiology of infectious diseases, cancer, and other chronic diseases as well as studies in psychiatric epidemiology (e.g., stage transitions from simple depression spells toward the more complex major depression syndromes with and without features of psychosis). Many of these investigations require methods that can identify pragmatically meaningful subgroups of individuals based on repeated measurements, and it is common for the repeated measurements to include some departure from perfect reliability. The LCPA model described in this research report should be well-suited for applications in longitudinal research on these topics as well.

In summary, this report has provided a thorough discussion of the specification, estimation, and application of the LCPA model. Our hope is that our demonstration using the data from the NLSY97 elucidates the model and that substantive practitioners will be able to use this demonstration in their own research. ML routines for latent Markov models, such as LTA and the “mover-stayer” model, are available in the software packages Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2007) and Latent GOLD (Vermunt and Magidson, 2005), and we believe that the results from our proposed LCPA model can be reproduced by those models. To this end, we have made the algorithms available in this manuscript, while the software was written in Intel Fortran and R code that is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant awards: 1 R21 DA025695 (Hwan Chung) and 5 K05 DA015799 (James C. Anthony).

Appendix

EM algorithm

The E-step computes the conditional probability that an individual i belongs to the class profile s and the class sequence c = (c1, …, cT), given a set of item responses yi = (yi1, …, yiT) and covariates xi,

| (5) |

The M-step maximizes the expected complete-data likelihood with respect to the model parameters. This likelihood can be written as

| (6) |

where θis = ∑c1 ⋯ ∑cT θi(s,c), and . The first sum in (6), which relates to the regression coefficients (i.e., the β-parameters), is the log-likelihood function for the multinomial logit model (Agresti, 2002), except that the unobserved counts for s are replaced by the fractional expectations ∑i θis. Updated estimates for the regression coefficients can be calculated with the standard Newton-Raphson method for multinomial logistic regression, provided that the computational routines allow fractional responses rather than integer counts. Because the primary and the secondary measurement parameters can be interpreted as parameters in a multinomial distribution when , and θis are known, we have

| (7) |

We can easily extend the EM algorithm to a model with missing observations on measurement items by using the missing at random (MAR) assumption (Rubin, 1987). In the E-step, the conditional probability of θi(s,c) is calculated only with the observed responses of yi. We denote to distinguish it from the previous θi(s,c) given in (5). The primary measurement parameter is then obtained from the provisional estimates by

| (8) |

where denotes the sets of individuals who respond to the mth item at time t, and denotes those who fail to respond to the mth item at time t. Because our data set contains missing observations on items, we will use (8) for our calculations.

The Hessian matrix for β

The elements in the diagonal blocks of the Hessian matrix for the regression coefficients given in (4) are

Where ; q, q′ = 1, …, p; s, s′ = 1, …, S − 1; and ζij = 1 if i = j and 0 otherwise.

Using the chain rule, the off-diagonal block of the Hessian matrix with respect to βs = (β1s, …, βps)′ and C − 1 free parameters in can be written as

| (9) |

for s = 1, …, S − 1; s′ = 1, …, S; and t = 1, …, T. In (9), is the vector of free parameters in , and GC consists of a (C − 1) × (C − 1) identity matrix in the first C − 1 columns and the vector of negative one in the last column (i.e., the Cth column). The elements of the H matrix given in (9) can be calculated as

where q = 1, …, p, s = 1, …, S − 1; s′ = 1, …, S; c = 1, …, C; and t = 1, …, T.

The off-diagonal block of the Hessian matrix with respect to βs and rm −1 free parameters in ρmt|c = (ρm1t|c, …, ρmrmt|c)′ is

| (10) |

for s = 1, …, S − 1; m = 1, …, M; t = 1, …, T; and c = 1, …,C. In (10), ψmt|c = (ρm1t|c, …, ρmrm−1t|c)′ is the vector of free parameters in ρmt|c. The elements of the U matrix given in (10) can be written as

where q = 1, …, p, s = 1, …, S − 1; m = 1, …, M; k = 1, …, rm; c = 1, …, C; and t = 1, …, T.

The Hessian matrix for β

Using the chain rule, the diagonal block of the Hessian matrix with respect to free parameters in and can be written

| (11) |

for s, s′ = 1, …, S; and t, t′ = 1, …, T. In (11), the elements of the R matrix are

Where ; c, c′ = 1, …, C; s, s′ = 1, …, S; and t, t′ = 1, …, T.

The off-diagonal block of the Hessian matrix with respect to the free parameters in and ρmt′|c′ can be written as

| (12) |

for s = 1, …, S; t, t′ = 1, …, T; m = 1, …, M; and c′ = 1, …, C. The elements of the A matrix in (12) can be written as

where c, c′ = 1, …, C; s = 1, …, S; t, t′ = 1, …, T; m = 1, …, M; and k = 1, …, rm.

The Hessian matrix for η

The diagonal block of the Hessian matrix with respect to the free parameters in ρmt|c and ρm′t′|c′ is

| (13) |

for m, m′ = 1, …, M; t, t′ = 1, …, T; and c, c′ = 1, …, C. The elements of the V matrix given in (13) can be calculated to be

Where ; m, m′ = 1, …, M; k = 1, …, rm; k′ = 1, …, rm′; t, t′ = 1, …, T; and c, c′ = 1, …, C.

Contributor Information

Hwan Chung, Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA; Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

James C. Anthony, Michigan State University, East Lansing, USA

Joseph L. Schafer, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, USA

References

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. Second. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Neumark YD, Van Etten ML. Do i do what i say? a perspective on self-report methods in drug dependence epidemiology. In: Stone AA, Turkkan JS, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman HS, Cain VS, editors. The Science of Self-Report: Implications for Research and Practice. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Miglioretti DL, Zeger SL, Rathouz PJ. Latent variable regression for multiple discrete outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1997;92:1375–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and suicide among racial/ethnic populations – 17 states, 2005–2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:637–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Lanza ST, Loken E. Latent transition analysis: inference and estimation. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:1834–1854. doi: 10.1002/sim.3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Park Y, Lanza ST. Latent transition analysis with covariates: Pubertal timing and substance use behaviors in adolescent females. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24:2895–2910. doi: 10.1002/sim.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS. Classification and course of alcohol problems among adolescents in addictions treatment programs. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1734–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS, Armstrong TD, Labouvie EW. Prevalence of dsm-iv alcohol diagnoses and symptoms in adolescent community and clinical samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:546–554. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clogg CC, Goodman LA. Latent structure analysis of a set of multidimensional contingency tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79:762–771. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM. Using latent transition analysis to examine the gateway hypothesis. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and Pathways of Drug Involvement: Examining the Gateway Hypothesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 254–269. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Graham JW, Long JD, Hansen WB. Crossvalidation of latent class models of early substance use onset. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1994;29:165–183. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2902_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Wugalter SE. Latent class models for stage-sequential dynamic latent variables. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1992;27:131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Deas D, P PR, Langenbucher J, Goldman M, Brown S. Adolescents are not adults: developmental considerations in alcohol users. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu W, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Anthony JC, Angermeyer M, Bruffaerts R, Girolamo G, Gureje O, Huang Y, Karam A, Kostyuchenko S, Lepine JP, Mora M, Neumark Y, Ormel JH, Pinto-Meza A, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Wells TTJE. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: Findings from the who world mental health surveys. PLOS Medicine. 2008;5:1053–1067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via em algorithm (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dierker LC, Vesela F, Sledjeskia EM, Costelloa D, Perrine N. Testing the dual pathway hypothesis to substance use in adolescence and young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective dtudy of public health problems sssociated with early drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111:949–955. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeland MA, Handelman SL. Using latent class models to characterize and assess relative error in discrete measurements. Biometrics. 1989;45:587–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR. Youth tobacco use: Risks, patterns, and control. In: Orleans C, Slade J, editors. Nicotine Addiction. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 360–384. [Google Scholar]

- Formann AK. Latent class model diagnosis from a frequentist point of view. Biometrics. 2003;59:189–196. doi: 10.1111/1541-0420.00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett ES, Zeger SL. Latent class model diagnosis. Biometrics. 2000;56:1055–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA. Exploratory latent structure analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika. 1974;61:215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Aveyard P, Fielding A, Sutton S. Using latent class and latent transition analysis to examine the transtheoreticalmodel staging algorithm and sequential stage transition in adolescent smoking. Substance Use and Misuse. 2009;44:2028–2042. doi: 10.3109/10826080902848665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Collins LM, Hill KG, Hawkins JD. Developmental pathways to alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2000;61:798–808. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeran T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among u.s. college students ages 1824: changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Jamanka A, Howard J. Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1527–1533. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R. Age of drinking onset and involvement in physical fights after drinking. Pediatrics. 2001;108:872–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. NIH Publication 09-7401. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Yamaguchi K. From beer to crack: developmental patterns of drug involvement. Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:851–855. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling RP. The political, social, and public health problems of binge drinking in college. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:195–198. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langeheine R, Pannekoek J, Pol Fv. Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in categorical data analysis. Sociological Methods and Research. 1996;24:492–516. [Google Scholar]

- Langeheine R, van de Pol F. Latent Markov chains. In: Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL, editors. Applied Latent Class Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 304–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM. A mixture model of discontinuous development in heavy drinking from ages 18 to 30: The role of college enrollment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:552–561. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld PF, Henry NW. Latent structure analysis. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Cleary PD. The smoking problem: A review of the research and theory in behavioral risk modification. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:370–405. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TS, Dayton CM. Model selection information criteria for non-nested latent class model. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1997;22:249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, Second edition. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Medell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, Health AC. Early-onset alcohol-use behaviors and subsequent alcohol-related driving risks in young women: a twin study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:798–804. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew KP, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:S61–S81. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RB. Efficient estimation and local identification in latent class analysis. Psychometrika. 1956;21:331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Mooijaart A. Log-linear and Markov modeling of categorical longitudinal data. In: Bijleveld CCJH, van der Kamp T, editors. Longitudinal Data Analysis: Designs, Models, and Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 318–370. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Nebury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the em algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks J. Binge drinking among us adults. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Frequency and sequence of drug use: a longitudinal study from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Drug Education. 1986;16:101–120. doi: 10.2190/1VKR-Y265-182W-EVWT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention. Drinking in America: Myhts, Realities and Prevention Policy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. In: Raftery AE, editor. Sociological Methodology 1995. Oxford: Blackwell; 1995. pp. 111–164. [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin BA, Ip EH, Wolfson M. Locally dependent latent class models with covariates: an application to under-age drinking in the usa. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A. 2008;171:877–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB, Stern HS. Testing in latent class models using a posterior predictive check distribution. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent Variables Analysis: Applications for Developmental Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. pp. 420–438. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Simon TR, Hammig BJ, Guerrero JL. Alcohol-consumption behaviors and risk for phusical fighting and injuries among adolescent drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:959–963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health Human Services. NIH Publication 04-5465. Wasington, DC: USDHHS; 2009. Understanding underage drinking. [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Redding CA, Anatchkova MD, Fava JL, Prochaska JO. Identifying cluster subtypes for the prevention of adolescent smoking acquisition. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent GOLD 4.0 user’s guide. Belmont, Massachusetts: Statistical Innovations, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272:1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]