Abstract

The present study reports a case of electrical storm occurring in a 43-year-old woman with dilated cardiomyopathy. The patient suffered from a cardiac electrical storm, with 98 episodes of ventricular tachycardia rapidly degenerating to ventricular fibrillation in hospital. The patient was converted with a total of 120 defibrillations. Recurrent ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation was initiated by premature ventricular beats. The patient did not respond to the use of amiodaronum. However, the administration of esmolol stabilized the patient's heart rhythm. A moderate dose of the β-blocker esmolol, administered as an 0.5-mg intravenous bolus injection followed by an infusion at a rate of 0.15 mg/kg/min, inhibited the recurrence of ventricular fibrillation and normalized the electrocardiographic pattern. The results suggest that esmolol may be able to improve the survival rate of patients with electrical storm in dilated cardiomyopathy and should be considered as a primary therapy in the management of cardiac electrical storms.

Keywords: cardiac electrical storm, dilated cardiomyopathy, esmolol, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation

Introduction

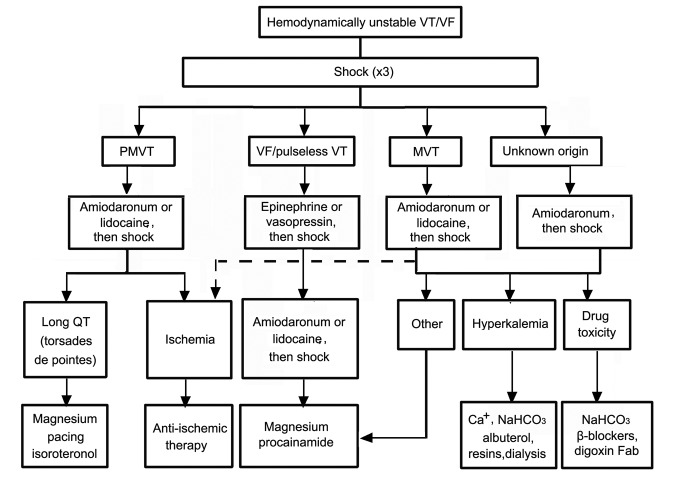

Electrical storm (ES) is a dramatic and life-threatening syndrome which is defined by three or more sustained episodes of ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), or appropriate shocks from an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator within 24 h (1–3). This pathology is may cause fatal arrhythmia in certain patients with severe heart disease (4,5). Once an electrical storm occurs, the control of ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation using standard treatment alone is difficult (6–9). A schematic of the emergent treatment of ventricular arrhythmias is shown in Fig. 1. ES can manifest itself during post-infarction ischemic heart disease, various forms of cardiomyopathy, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, or an inherited arrhythmic syndrome, such as Brugada syndrome (1,10–16). ES typically has a poor outcome (17). The intravenous injection of class III antiarrhythmic drugs, including, amiodaronum and nifekalant, is used initially to inhibit ventricular arrhythmia in the majority of patients (18,19). However, electrical storms can show resistance to, or not be affected by these drugs, which is a major problem in the application of emergency medical care (20,21). In the present study, a case of ventricular electrical storm in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy is reported, that was successfully treated by esmolol infusion.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the emergent treatment of VT/VF. VT, ventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; PMVT, polymorphic VT; MVT, monomorphic VT; Fab, fragment antigen binding compound.

Case report

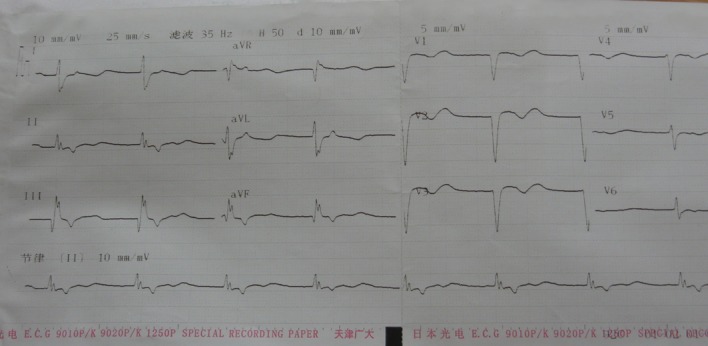

A 43-year-old woman was referred to the Department of Cardiology, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University (Jinan, China) on December 3, 2010. She underwent two defibrillator shocks within 24 h after having survived sudden cardiac death. The patient presented with a respiratory infection 20 days prior to admission. An intercritical electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded upon admission using a 6-channel ECG system (ECG-1250P; Nihon Kohden, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) which detected a sinus rhythm and intraventricular block (Fig. 2). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed markedly enlarged left ventricular end-diastolic dimension [76 mm; normal range (NR), 42.5±7.5 mm] and lowered left ventricular ejection fraction (18%; NR, 65±5%), mild mitral regurgitation and mild elevation of pulmonary arterial pressure (pulmonary artery mean pressure, 34 mm Hg; NR, 10±5 mmHg). Dilated cardiomyopathy is a myocardial disease characterized by dilatation and impaired contraction of the left ventricle or both ventricles (22). The patient presented with sudden arrhythmic death. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed dilated cardiomyopathy with severe global left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 18%. These symptoms excluded ischemic heart disease and led to a diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram showing sinus rhythm and intraventricular block.

Initial laboratory tests revealed hypokalemia (2.9 mmol/l; NR, 4.4±0.9 mmol/l), high serum B-type natriuretic peptide (739 pg/ml; NR, <100 pg/ml), normal magnesium levels, no hypercalcemia, and normal troponin I and creatine phosphokinase enzyme levels. Following admission, the patient was under close observation. Genetic testing was not performed, and the patient had no family history of dilated cardiomyopathy. Informed consent was obtained from the patient on the day of admission. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University.

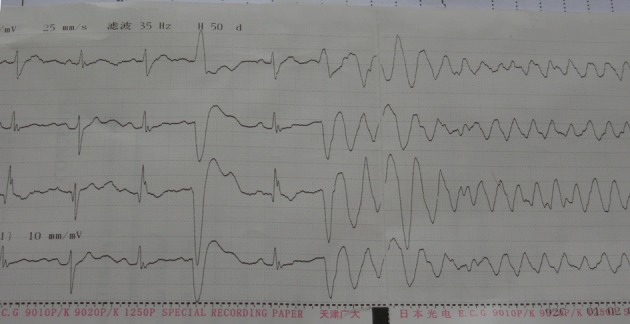

In the following duration of hospital stay, 40 episodes of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation occurred within 24 h; recurrent polymorphic non-sustained and sustained ventricular tachycardia, triggered by ventricular premature beat, appeared incessantly and degenerated into polymorphic sustained ventricular tachycardia (Fig. 3). Repeated electrical cardioversion procedures were performed (54 in total). Firstly, the patient was prescribed high-dose amiodaronum (2 mg/min; ivp; Sanofi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Paris, France), which is a class III antiarrhythmic drug, but gradual tapering of the amiodaronum infusion resulted in the recurrence of the electrical storm, which required frequent cardioversions. One day later, 58 episodes of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation occurred repeatedly, repeated electrical cardioversion procedures were performed (66 in total, indicating that the electrical storm exhibited resistance to amiodaronum. A number of clinical studies have demonstrated that β-blockers effectively suppress electrical storm (23–26); therefore, middle-dose esmolol (0.05–0.2 mg/kg/min; ivp; Oilu Pharmaceutical Co/. Ltd., Jinan, China), which is a β1-receptor blocker, was prescribed (20,21). Following an intravenous bolus injection of 0.5 mg esmolol, an infusion of esmolol at a rate of 0.15 mg/kg/min (ivp) was administered. No ventricular fibrillation occurred repeatedly during an interruption of the infusion for 24 h. The patient was free of ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, although the premature ventricular beats persisted for 2 weeks following the application of esmolol (Fig. 4). The patient received oral bisoprolol fumarate (β-blockade; 5 mg/day; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) to treat these premature ventricular beats until she was discharged on January 7, 2011.

Figure 3.

Electrocardiogram showing an episode of sinus rhythm with multiple ventricular premature beats spontaneously converted to ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation.

Figure 4.

Electrocardiogram following the infusion of esmolol; a reduction in the occurrence of ventricular fibrillation was recorded. Although the premature ventricular beats persisted for several hours with the same coupling interval, the patient was free of ventricular fibrillation.

During the treatment of the electrical storm, serum electrolytes (including Mg2+, K+ and Ca2+) were maintained at high levels by the infusion of intravenous electrolyte solution. When the acute phase of the electrical storm was controlled, the focus of treatment shifted toward maximizing heart-failure therapy and preventing subsequent ventricular arrhythmias. The patient was prescribed oral losartan (angiotensin receptor blocker; 50 mg/day; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland), oral bisoprolol fumarate (β-blockade; 5 mg/day), oral spironolactone (aldosterone antagonist; 20 mg twice daily), oral digoxin (digitalis; 0.125 mg/day; both Shanghai Xinyi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) furosemidum (loop diuretic; 40 mg twice daily; ivp; Shanghai He Feng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Following this, the patient discharged on January 7, 2011 in a hemodynamically stable condition.

Discussion

Typically, electrical storms have a poor prognosis; they are defined as three or more distinct episodes of ventricular fibrillation, or hemodynamically destabilizing ventricular tachycardia occurring within a 24-h period, typically requiring treatment with electrical cardioversion or defibrillation (4).

Enhanced sympathetic nerve activity is associated with episodes of ES (27,28) and β-blockade has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of recurrent VT and VF (25). For patients with acute myocardial infarction, the use of β-blockade decreases the risk of sudden death, as β-blockers reduce mortality by preventing VT and VF (26). β-blockers treatment should be limited in patients with labile hemodynamic compensation or severe reduction of LV function. An electrical storm in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy occurs rarely with only a few reported cases. Once non-ischemic cardiomyopathy occurs, the heart experiences structural changes. Fibrosis results in scarring, which leads to regions of conduction block; however, groups of myofibrils are able to survive, particularly those surrounding the border of the scar. Slow conduction through these regions can facilitate electrically stable reentry (29–32).

It is acknowledged that amiodaronum and β-blockers, particularly the former, are able to treat arrhythmia effectively in the majority of patients. The present study presents an organized approach for effectively evaluating and managing electrical storms. β-blocker administration has antiarrhythmic and antiadrenergic effect. Its administration should be limited in patients with severe reduction of LV function or haemodynamic instability. Esmolol is a selective ultra short β1 blocker. The present study presents esmolol for effectively managing electrical storms in dilated cardiomyopathy with severe reduction of LV function or haemodynamic instability. Firstly, a high dose of amiodaronum was prescribed to treat cardiac electrical storm in a patient experiencing dilated cardiomyopathy. However, when gradual tapering of the amiodaronum infusion did not arrest the electrical storm, and frequent cardioversions were required, esmolol was administered in a bolus injection, followed by an infusion. Following this, there were no further frequent repeats of ventricular fibrillation. This suggests that esmolol is effective in suppressing electrical storms, and that enhanced sympathetic nerve activity is involved in episodes of electrical storms (26,33).

In conclusion, the results strongly suggest that esmolol may improve the survival rates of patients experiencing electrical storms, and should be considered as a primary treatment option. However, as esmolol can exacerbate heart failure in patients with poor systolic function, its use in these patients should be closely monitored.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by The National Natural Science Funds for Young Scholar (grant no. 81200211), the Shandong Young Scientists Award Fund (grant no. BS2012SW003) and the Scientific and Technology Development program of Jinan (grant no. 20120144).

References

- 1.Conti S, Pala S, Biagioli V, Del Giorno G, Zucchetti M, Russo E, Marino V, Dello Russo A, Casella M, Pizzamiglio F, et al. Electrical storm: A clinical and electrophysiological overview. World J Cardiol. 2015;26:555–561. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i9.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sesselberg HW, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Zareba W, Daubert JP, Andrews ML, Hall WJ, McClinitic B, Huang DT. MADIT-II Research Group: Ventricular arrhythmia storms in postinfarction patients with implantable defibrillators for primary prevention indications: A MADIT-II substudy. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Exner DV, Pinski SL, Wyse DG, Renfroe EG, Follmann D, Gold M, Beckman KJ, Coromilas J, Lancaster S, Hallstrom AP. AVID Investigators: Electrical storm presages nonsudden death: The antiarrhythmics versus implantable defibrillators (AVID) trial. Circulation. 2001;103:2066–2071. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.16.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis JE, Curtis LA, Rashid H. Idiopathic cardiac electrical storm. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrouche NF, Verma A, Wazni O, Schweikert R, Martin DO, Saliba W, Kilicaslan F, Cummings J, Burkhardt JD, Bhargava M, et al. Mode of initiation and ablation of ventricular fibrillation storms in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1715–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koplan BA, Stevenson WG. Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:289–297. doi: 10.4065/84.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ECC Committee, Subcommittees Task Forces of the American Heart Association 2005 American Heart Association: Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2005;112:IV1–IV203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittadodla PS, Salen PN, Traub DM. Isoproterenol as an adjunct for treatment of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation storm in a pregnant woman. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:251.e3–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miwa Y, Ikeda T, Mera H, Miyakoshi M, Hoshida K, Yanagisawa R, Ishiguro H, Tsukada T, Abe A, Yusu S, Yoshino H. Effects of landiolol, an ultra-short-acting beta1-selective blocker, on electrical storm refractory to class III antiarrhythmic drugs. Circ J. 2010;74:856–863. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bänsch D, Oyang F, Antz M, Arentz T, Weber R, Val-Mejias JE, Ernst S, Kuck KH. Successful catheter ablation of electrical storm after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108:3011–3016. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103701.30662.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yusu S, Ikeda T, Mera H, Miyakoshi M, Miwa Y, Abe A, Tsukada T, Ishiguro H, Shimizu H, Yoshino H. Effects of intravenous nifekalant as a lifesaving drug for severe ventricular tachyarrhythmias complicating acute coronary syndrome. Circ J. 2009;73:2021–2028. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Remo BF, Preminger M, Bradfield J, Mittal S, Boyle N, Gupta A, Shivkumar K, Steinberg JS, Dickfeld T. Safety and efficacy of renal denervation as a novel treatment of ventricular tachycardia storm in patients with cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefanelli CB, Bradley DJ, Leroy S, Dick M, II, Serwer GA, Fischbach PS. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy for life-threatening arrhythmias in young patients. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2002;6:235–244. doi: 10.1023/A:1019509803992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatzoulis KA, Andrikopoulos GK, Apostolopoulos T, Sotiropoulos E, Zervopoulos G, Brili S, Stefanadis CI. Electrical storm is an independent predictor of adverse long-term outcome in the era of implantable defibrillator therapy. Europace. 2005;7:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meregalli P, Wilde A, Tan H. Pathophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome: Depolarization disorder, repolarization disorder, or more? Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bettiol K, Gianfranchi L, Scarfo S, Pacchioni F, Pedaci M, Alboni P. Successful treatment of electrical storm with oral quinidine in Brugada syndrome. Ital Heart J. 2005;6:601–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowey PR. An overview of antiarrhythmic drug management of electrical storm. Can J Cardiol. 1996;12:3B–8B. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Herendael H, Dorian P. Amiodarone for the treatment and prevention of ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:465–472. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurisu K, Hisahara M, Onitsuka H, Sekiya M, Ikeuchi M, Kozai T, Urabe Y. Nifekalant hydrochloride terminated electrical storms after coronary surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1637–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorajja D, Munger TM, Shen WK. Optimal antiarrhythmic drug therapy for electrical storm. J Biomed Res. 2015;29:20–34. doi: 10.7555/JBR.29.20140147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eifling M, Razavi M, Massumi A. The evaluation and management of electrical storm. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38:111–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, Maisch B, Mautner B, O'Connell J, Olsen E, Thiene G, Goodwin J, Gyarfas I, et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology task force on the definition and classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 1996;93:841–842. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva Marques J, Veiga A, Nóbrega J, Correia MJ, de Sousa J. Electrical storm induced by H1N1 A influenza infection. Europace. 2010;12:294–295. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balcells J, Rodriguez M, Pujol M, Iglesias J. Successful treatment of long QT syndrome-induced ventricular tachycardia with esmolol. Pediatr Cardiol. 2004;25:160–162. doi: 10.1007/s00246-003-0620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators: Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nademanee K, Taylor R, Bailey WE, Rieders DE, Kosar EM. Treating electrical storm: Sympathetic blockade versus advanced cardiac life support-guided therapy. Circulation. 2000;102:742–747. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.7.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lombardi F, Verrier RL, Lown B. Relationship between sympathetic neural activity, coronary dynamics and vulnerability to ventricular fibrillation induced by myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am Heart J. 1983;105:958–965. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zipes DP. Influence of myocardial ischemia and infarction on autonomic innervation of heart. Circulation. 1990;82:1095–1105. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.82.4.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hershberger RE, Morales A, Siegfried JD. Clinical and genetic issues in dilated cardiomyopathy: A review for genetics professionals. Genet Med. 2010;12:655–667. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f2481f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Streitner F, Herrmann T, Kuschyk J, Lang S, Doesch C, Papavassiliu T, Streitner I, Veltmann C, Haghi D, Borggrefe M. Impact of shocks on mortality in patients with ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy and defibrillators implanted for primary prevention. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolettis TM, Naka KK, Katsouras CS. Radiofrequency catheter ablation for electrical storm in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2005;46:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takigawa M, Noda T, Kurita T, Aihara N, Yamada Y, Okamura H, Satomi K, Suyama K, Shimizu W, Kamakura S. Predictors of electrical storm in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy - how to stratify the risk of electrical storm. Circ J. 2010;74:1822–1829. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burjorjee JE, Milne B. Propofol for electrical storm; a case report of cardioversion and suppression of ventricular tachycardia by propofol. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:973–977. doi: 10.1007/BF03016886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]