Abstract

Canine deviation from its path of eruption is usually followed by either delayed or impaction of canine. One of the important and not so noticed reasons for canine displacement is formerly impacted central incisor. The difference in age of eruption of these two teeth is 4 years; however, the absence of maxillary incisor should be perceived with utmost conviction about impending canine displacement leading to its impaction as well. This case presents similar picture where composite, compound odontoma with respect to maxillary central incisor led to its impaction resulted in deviated path of eruption for erupting canine. This canine displacement to worsen prognosis ended up getting impacted if not dealt with cautiously in the later stages of occlusal development.

Keywords: Canine, central incisor, compound odontoma

Introduction

The spectacle of erupted lateral incisors associated with the nonappearance of one or both central incisors should always be deemed abnormal whether or not deciduous central incisor is still present The early diagnosis of condition to ascertain the reason for aberration is needed as impacted central incisors are usually first diagnosed at 7–8 years of age which is 4 years before eruption of permanent canines.[1] Thus, although a chronological hiatus of approximately 4 years separates the normal and the unaffected eruption times of the two teeth, their anatomic proximity invites investigation of an etiologic association.[2] The frequent disturbance of canine eruption on the ipsilateral side of formerly impacted central incisor has been reported in 41.3% cases.[3]

Among the rare causes which prevent eruption of the central incisors are odontomas. Odontomas are hamartomatous lesions rather than true neoplasms which are classified into compound and complex.[4] Compound odontomas are malformations in which all the tissues are in organized pattern giving resemblance to the tooth. These are variable in size and shape; however, whether they are complex or composite type, they usually have broader and wider cross-section and their presence will be more likely to impede the eruption of the central incisors than a supernumerary tooth.[5]

The aim of this article is to present (i) the successful treatment of a patient whose permanent maxillary central incisor was impacted and presented with compound composite odontoma and (ii) to draw attention with a diagnostic view toward the impending ipsilateral canine impaction.

Case Report

An 8.2-year-old female patient reported to the department of pediatric dentistry with a chief complaint of missing right upper central incisor. The family medical and dental histories were noncontributory. The parents were unable to recall any trauma to the oral cavity or head and neck region. Extraoral examination revealed bilaterally symmetrical face and straight facial profile. Intraoral examination revealed that the patient is in mixed dentition period with erupted permanent maxillary and mandibular central and lateral incisors, except for permanent maxillary right central incisor [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Intraoral photograph showing impacted permanent right central incisor and erupted permanent lateral incisors

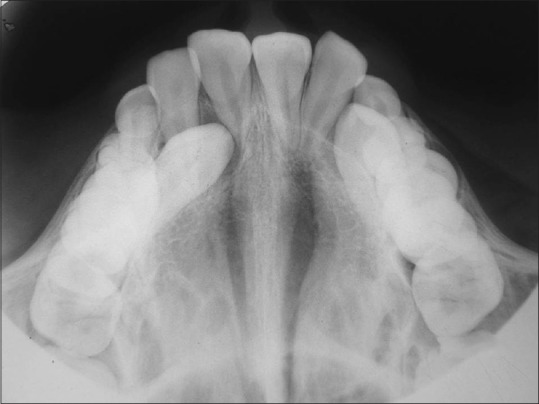

An intraoral periapical radiograph (Clark's technique) revealed the presence of two lesions of compound odontomas in the labial region of the right maxillary central incisors, and an upper anterior occlusal film [Figure 2] revealed two tooth-like structures of different shapes and sizes in relation to the crown of the impacted permanent maxillary right central incisor. They were surrounded by a well-circumscribed radiolucent zone. The permanent maxillary right central incisor was displaced and laid labially in relation to the apical third of the root of the permanent maxillary left central incisor.

Figure 2.

Maxillary occlusal radiograph showing incomplete root formation and two radio-opaque denticles overlying crown of unerupted tooth

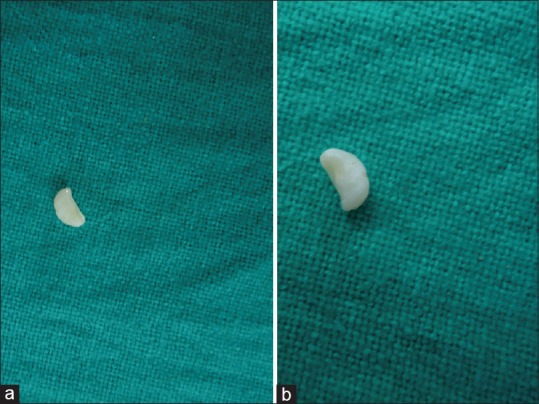

Upon the clinical and radiographic findings, a provisional diagnosis of a compound composite odontoma was made. It was decided to surgically enucleate the tumor and finally wait for the spontaneous eruption of impacted central incisor. Under local anesthesia, labial mucoperiosteal flap was elevated, the thin bone overlying was removed to extract the two tooth-like structures known as denticles, and the size of the denticles varied from 4 mm to 5 mm [Figure 3a and b]. The flap was closed and the healing was uneventful.

Figure 3.

(a) First tooth like denticle of size 4-5mm. (b) Second tooth like denticle of size 4-5mm with similiar structure

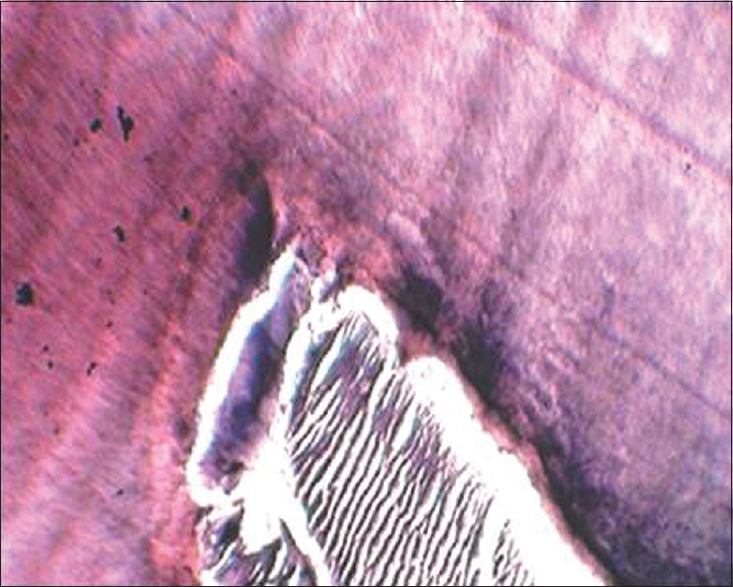

Histopathologically, the sections revealed miniature teeth containing dentin with normal arrangement of dentinal tubules, pulp, cementum, and periodontal ligament-like tissue. By correlating the clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings, a definite diagnosis of compound odontoma was made [Figure 4]. It was arranged for the patient to follow-up for the management of the impacted permanent central incisor.

Figure 4.

Enamel matrix adjacent to highly organized and differentiated dentin (H and E, ×40)

Discussion

Odontomas are relatively common odontogenic lesions, generally asymptomatic, and are rarely diagnosed before the second decade of life.[6] They frequently lead to impacted or delayed eruption of permanent teeth. Compound odontomas are usually located in the anterior sector of maxilla, over the crowns of unerupted teeth, or between the roots of erupted teeth.[6] The lesions are usually unilocular and contain multiple radiopaque, miniature tooth-like denticles. There are three main types of compound composite odontomas.[7] Denticular type composed of two or more separate denticles, each having a crown and a root or epithelial sheath of Hertwig with a distribution of dental hard tissues comparable to that found in a tooth. Particulate type composed of two or more separate masses or particles bearing no macroscopic resemblance to a tooth and consisting of hard dental tissues abnormally arranged. Denticulo particulate type – in this type, denticles and conglomerate masses or particles are present side by side. In the present case, the denticular type was identified as two separate denticles leading to impaction of the permanent central incisor.

There is more or less a standard protocol for the management of impacted central incisors that are anatomically normal in their development.[8] The recommended treatment is as follows:

Adequate space is prepared for the tooth in the arch

Cause of noneruption (usually a supernumerary or odontomas) should be eliminated.

Early diagnosis of the maxillary central incisor impactions with surgical removal of supernumerary tooth-coupled with adequate space is helpful in spontaneous eruption of the impacted maxillary central incisors.[9] If the impacted tooth is diagnosed at a later stage with its root completely formed or if present in the unfavorable position, combination of surgical and orthodontic treatment has to be carried out. If the root of the impacted tooth is still developing, the tooth may erupt normally; however, once the root apex has closed, the tooth has lost its potential to erupt.[10] In the present case, the root formation was not complete and tooth was expected to erupt spontaneously after the surgical removal of odontoma since adequate space to accommodate erupting incisor was present. At the end of the treatment, the patient showed normal clinical crown length with acceptable gingival contour due to spontaneous eruption.

Mills [11] advocated that exposure of the permanent tooth during the procedure to remove the supernumerary teeth should not be done and mechanotherapy to bring down the central incisor should be avoided as the teeth often erupt spontaneously with labial bony plate and good width of attached gingival. There is no attached gingiva gingival level discrepancy between adjacent teeth if the use of appliances in bringing down central incisors is avoided. Spontaneous eruption of impacted maxillary incisors occurs in 54–76% of cases when obstruction is removed and if there is enough space in the dental arch.[12] However, research data indicated that the spontaneous eruption of impacted maxillary incisor may take up to 3 years and sometimes, orthodontic treatment is necessary to achieve adequate alignment of the erupted tooth in the dental arch.[13,14] In this case, spontaneous eruption of tooth occurred within span of 1.3 years which is clinically acceptable time to achieve proper eruption timetable [Figures 5 and 6].

Figure 5.

Intraoral photograph showing erupted permanent right central incisor and patient is still in mixed dentition period

Figure 6.

Maxillary occlusal radiograph showing change in path of eruption of ipsilateral canine, and contralateral side,permanent canine if following normal path of eruption

As a general rule, treatment priority should be given to unerupted central incisor and all other procedures should be delayed until the incisors are in alignment.[5] While bringing the incisors into alignment, the eruption of ipsilateral canine has to be observed with long and careful follow-up so that the patient should be advised of the possibility of ectopic/impacted canines in the future and the need of the second surgical exposure of canine followed by mechanotherapy to guide the eruption of permanent canines. In the present case, patient followed during the eruption of permanent right central incisor, and during follow-up, it was seen that the expected Ugly Duckling stage picture could not be conceived from the intraoral view. Further, when justified radiographically [Figure 7], adjacent lateral incisor root was seen to be displaced distally when compared with the contralateral lateral incisor's normally positioned root, and therefore, the lateral incisor alters its (desirable) relationship with the adjacent canine at a very critical stage of the latter's development. An environment was created in which the lateral incisor root became an obstacle, leading to an altered mesial position of the canine. If we summarize, it would not be wrong to say that due to delayed eruption of the central incisor, there was a significant reduction in the arch's capacity to accommodate the canine leading to its impaction. Chaushu et al.[4] showed the same that whenever there is impacted central incisor, the adjacent lateral incisor root is displaced distally by a mean of 5 mm as compared with the contralateral lateral incisor's normally positioned root. Therefore, such an environment is created leading to impaction of canine.

Figure 7.

Intraoral periapical radiographs of the erupting central incisor and change in path of eruption of erupting canine during follow-up of 2 years. (a) Preoperative intraoral periapical radiograph showing impacted central incisor and presence of two tooth-like denticles. (b) After 1 year follow-up showing movement of impacted maxillary central incisor. (c) Intraoral radiograph showing 1. years of follow-up. (d) Radiograph showing complete eruption of impacted incisor after 2 years

Eruption time is the prime factor here, due to which the incisors and canine across the arch erupt synchronously and attain desired position which unfortunately does not happen in our area of interest. Impedance in the rate of incisor eruption has abstained the lateral incisor not to straighten in turn leading to malpositioning of ipsilateral canine. The association between the two conditions has been overlooked; their concomitant occurrence is regarded which in turn as coincidental and articles about them have largely been more for curiosity value. Although, as pediatric dentists, the focus of the treatment revolves around removal of compound odontoma and correction of impacted central incisor, no case report in the literature followed the case for so long to judge the fate of erupting ipsilateral canine.

Conclusions

The following findings have clinical relevance as follows:

Patients who require treatment for impacted incisors should be advised of the possibility of ectopic/impacted canines in the future and the need for careful follow-up.

Canine position should be regularly monitored after the removal of obstruction and during eruption of permanent central incisor.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995. pp. 531–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wasserstein A, Tzur B, Brezniak N. Incomplete canine transposition and maxillary central incisor impaction – A case report. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:635–9. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cawson RA, Binnie WH, Eveson JW. Clinical and Pathological Correlations. Hong Kong: Mosby-Wolfe; 1993. Color Atlas of Oral Disease; pp. 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaushu S, Zilberman Y, Becker A. Maxillary incisor impaction and its relationship to canine displacement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:144–50. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker A. Orthodontic treatment of impacted teeth. 3rd ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. Maxillary Central Incisors; pp. 70–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budnick SD. Compound and complex odontomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;42:501–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafer GW, Hine MK, Levy BM. A Textbook of Oral Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983. pp. 308–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houston WJ, Tulley WJ. A Textbook of Orthodontics. Bristol: John Wright; 1986. pp. 126–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smailiene D, Sidlauskas A, Bucinskiene J. Impaction of the central maxillary incisor associated with supernumerary teeth: Initial position and spontaneous eruption timing. Stomatologija. 2006;8:103–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokich VG, Mathews DP. Surgical and orthodontic management of impacted teeth. Dent Clin North Am. 1993;37:181–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills JR. Principles and Practice of Orthodontics. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garvey MT, Barry HJ, Blake M. Supernumerary teeth – An overview of classification, diagnosis and management. J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65:612–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason C, Azam N, Holt RD, Rule DC. A retrospective study of unerupted maxillary incisors associated with supernumerary teeth. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38:62–5. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1999.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witsenburg B, Boering G. Eruption of impacted permanent upper incisors after removal of supernumerary teeth. Int J Oral Surg. 1981;10:423–31. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(81)80079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]