Abstract

Background

Research examining substance users’ recovery has focused on individual-level outcomes while paying limited attention to the contexts within which individuals are embedded, and the social processes involved in recovery.

Objectives

This paper examines factors underlying African American cocaine users’ decisions to reduce or quit cocaine use and uses practice theory to understand how lifestyle changes and shifts in social networks facilitate access to the capital needed to change cocaine use patterns.

Methods

The study, an in-depth analysis of substance-use life history interviews carried out from 2010 to 2012, included 51 currently not-in-treatment African American cocaine users in the Arkansas Mississippi Delta region. A blended inductive and deductive approach to data analysis was used to examine the socio-cultural and economic processes shaping cocaine use and recovery.

Results

The majority of participants reported at least one lifetime attempt to reduce or quit cocaine use; motivations to reduce use or quit included desires to meet social role expectations, being tired of using, and incarceration. Abstinence-supporting networks, participation in conventional activities, and religious and spiritual practices afforded access to capital, facilitating cocaine use reduction and sobriety.

Conclusions

Interventions designed to increase connection to and support from non-drug using family and friends with access to recovery capital (e.g., employment, faith community, and education) might be ideal methods to reduce substance use among minorities in low-income, resource-poor communities.

Keywords: African Americans, capital, cocaine use, recovery without treatment, rural/urban differences, social networks, southern United States

Introduction

Research suggests 99% of cocaine use-dependent African Americans have achieved at least temporary remission at some point in their substance use history (Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). Although drug use treatment services are one way to achieve remission from alcohol and drugs, it is increasingly apparent that recovery without treatment is common and perhaps even more prevalent among ethnic and racial minorities than among Whites (Perron et al., 2009). Research consistently shows recovery without treatment is a pathway to remission from nicotine dependence, alcohol, and drugs (Cohen, Feinn, Arias, & Kranzler, 2007; Klingemann, Sobell, & Sobell, 2010; Sobell, Ellingstad, & Sobell, 2000). Despite evidence that contextual factors are linked to drug use and recovery (Page & Singer, 2010), few studies examine the social contexts within which individuals are embedded, or the social processes and valued resources involved in recovery (Granfield & Cloud, 2001).

Multiple studies underscore the importance of investigating the social and economic contexts of drug use to better understand how social networks shape substance use outcomes. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions, specifically poverty, underpin the formation and maintenance of social networks perpetuating high-risk behaviors (including drug use) among disadvantaged African Americans in the South (Adimora, Schoenbach, & Doherty, 2006; Williams & Latkin, 2007). Qualitative and ethnographic studies in impoverished Hispanic communities found family networks providing emotionally close relationships and instilling dependence and loyalty to the family put young people born into intergenerational, drug-using families at risk for heroin use (Garcia, 2010; Valdez, Neaigus, & Kaplan, 2008). Similarly, ethnographic work among Northern United States African Americans living in severely distressed inner-city households revealed that norms embedded within family networks, including behaviors that offer children little protection from exposure to violence and drug use, increased risk for cocaine use (Dunlap, 1992; Dunlap, Golub, & Johnson, 2006).

Changes in substance use outcomes are an essential aspect of the recovery process. However, as the above studies demonstrate, the context within which those changes occur is also important: “...recovery from addiction is more than the absence of substance use in an otherwise unchanged life” (Laudet & White, 2008, p. 3). Indeed, shifts from drug-using to non-drug using networks, and engagement with conventional life and non-drug using support networks are critical to the recovery process. Non-drug-using social networks facilitate substance users’ re-engagement with employment and religion, adherence to conventional social roles and expectations, and re-establishing meaningful social relationships and a greater sense of belonging (Granfield & Cloud, 2001). Accessing recovery capital, which includes internal (e.g., self-worth and self-meaning) and external (e.g., social support and religion) resources needed to initiate and maintain recovery from drug addiction, is a critical component of the recovery process (Granfield & Cloud, 2001; Hodge, Marsiglia, & Nieri, 2011; Laudet & White, 2008).

During this study, our focus was social network influence on cocaine use among African Americans in the Arkansas Mississippi Delta region. Cocaine use has increased substantially among African Americans in some of the poorest and most underserved areas of the U.S., including rural residents in the Arkansas Mississippi Delta region (Booth, Leukefeld, Falck, Wang, & Carlson, 2006). Rural Arkansas cocaine users have significantly lower treatment participation when compared with similar users in other rural areas (Carlson, Wang, Siegal, Falck, & Guo, 1994) and face multiple barriers to access formal drug treatment services (Sexton, Carlson, Leukefeld, & Booth, 2008). Additionally, African American cocaine users in the South may feel alienated from the dominant culture of recovery because programs do not typically involve support from others in the African American community (e.g., Black churches and leaders) (Emma J. Brown, Hill, & Giroux, 2004).

Historically, African Americans in disadvantaged neighborhoods in the South relied heavily on extended family and church-based networks for support and help with day-to-day living (Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2003). Not surprisingly, African Americans in the Arkansas Delta continue to rely on these networks by seeking informal help from clergy to reduce substance use (Cheney et al., 2014; Sexton et al., 2008). Despite the demonstrated reliance on social support in these communities, no published studies could be located regarding the role of social networks and their embedded resources/capital in substance use outcomes (e.g., controlled use and recovery) in this population. This paper fills this gap through an examination of the factors underlying African American cocaine users’ decisions to reduce or quit cocaine use, highlighting the role of resources/capital embedded within social networks in changing cocaine use patterns (Cheney et al., 2014; Sexton, Carlson, Siegal, Leukfeld, & Booth, 2006). Addressing this knowledge gap is needed to effectively design culturally sensitive interventions involving local support networks for implementation in low-income, predominantly African American communities where there has traditionally been a reliance on the family and church.

Practice Theory: Its Application to Reduced Use and Recovery

Bourdieu's (1977) notion of “capital,” including social (e.g., social support), economic (e.g., employment), and cultural (e.g., education) capital, is especially useful in building a theory regarding the effects of the social position and context in which substance users are embedded, and how these relate to the accumulation of resources or capital required for recovery. According to Bourdieu (1977), individual action is negotiated by the lifestyle, values, norms, and expectations of particular social groups (in this case, southern African Americans) and is constrained by institutional power structures, which influence social position and the acquisition of valued resources (or capital).

Access to employment and other resources, especially abstinence-supporting friends and family members, influences an individual's ability to reduce use and achieve sobriety (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2006; Granfield & Cloud, 2001). As Brown and Trujillo (2003) found, supportive, non-drug using social networks moderated the negative consequences of chronic substance use among African American cocaine users in the South. Others found greater amounts of “recovery capital” (defined as social support, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning, and 12-step affiliation), were linked to improved quality of life and reduced stress, and were critical components of sustained recovery over time among inner-city minority substance users with a history of illicit drug use (primarily crack, then heroin) (Laudet, Morgen, & White, 2006; Laudet & White, 2008).

These studies demonstrate how the personal, social, and economic resources tied to social position are central to recovery from substance use in urban populations. However, little is known regarding the effects on cocaine use outcomes in social networks among disadvantaged African Americans in rural areas such as the Arkansas Delta. Drawing on practice theory, we illustrate how substance use is entwined with social networks and capital and the influence of opportunity structures and the allocation of resources on an individual's ability to reduce use and/or achieve recovery.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting

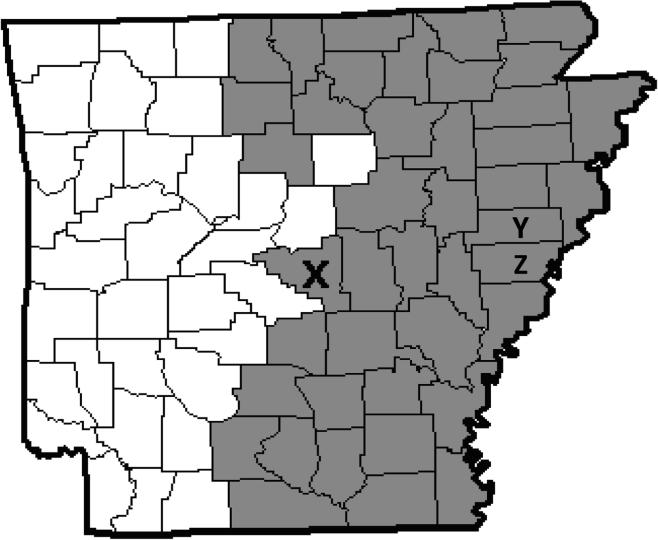

The study was conducted from 2010 to 2012 in urban and rural locations within Arkansas’ Mississippi River Delta Region in the southern U.S. The Mississippi Delta Region, which includes Arkansas and areas of seven other states, is an alluvial floodplain that was once one of the wealthiest regions of the U.S., particularly rich in cotton and hardwood lumber production (Saikku, 2010). The Arkansas Delta spans 250 miles north to south and as wide as 91 miles west of the Mississippi River. The Delta's population is ~441,000; 55.7% of whom live in urban and 44.3% in rural areas (DFA, 2011; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). In this study, we define the Arkansas Delta using the 42 counties targeted by the Delta Regional Authority, a federal agency working to stimulate economic development and improve the quality of life in the region (Allgov.com, 2015; “Consolidated Appropriations Act,” 2001; “Rural Development, Agriculture, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act,” 1989). Pulaski County (“X”), the urban setting where the City of Little Rock is located, and St. Francis (“Y”) and Lee Counties (“Z”), the rural settings, are in the Arkansas Delta Region (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mississippi Delta Region of AR. The grey areas are counties within the Delta Region; counties whose populations were specifically studied in this manuscript are indicated with X (Pulaski County), Y (St. Francis County), and Z (Lee County).

Near the turn of the 20th century, agricultural mechanization resulted in lower demand for farmers and labor which, coupled with limited economic and social opportunities, created significant disparities in this region (Stroud, 2014). Today, the Arkansas Mississippi River Delta Region is one of the most impoverished areas of the U.S. and is characterized by strained race relations, a stagnant economy, high unemployment, low incomes, and substantial emigration (Rogers, 2006; Stroud, 2014). According to 2012 county-level estimates, the percent of persons in the area who live in poverty ranges from 16% to 64% (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2013). In addition to social and economic disadvantage, Delta residents experience significant health disparity rates and limited healthcare resources (Felix & Stewart, 2005).

Study design and procedures

The analysis presented in this article is part of a sequential mixed-methods study of African American cocaine users’ perceived need for substance abuse treatment and HIV testing (Creswell, Klassen, Plano Clark, & Smith, 2011). In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted and collected data were used to develop structured questions and modify existing instruments subsequently administrated in a larger-scale, quantitative survey. In this paper, we report qualitative data findings only. The study received full ethical approval from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse issued a Certificate of Confidentiality. Participants were informed of the purpose of the study and assured that their participation was voluntary and their responses were confidential. All participants provided written informed consent.

To be eligible for the study, individuals had to: 1) be at least 18 years old; 2) be of African American race; 3) report non-injection cocaine use at least twice in the prior 30 days; 4) report no formal drug use treatment/counseling/self-help meeting attendance in the past 30 days; and 5) provide a verifiable residence address in one of the study counties.

Participants were recruited using the non-probabilistic Respondent-Driven Sampling (RDS; Heckathorn, 1997) method that is particularly useful to recruit “hidden populations” such as illegal drug users. RDS also produces a more representative sample of hidden populations than can be obtained through targeted or snowball sampling (Heckathorn, Semaan, Broadhead, & Hughes, 2002). Initial study participants (“seeds”) were identified through ethnographic mapping techniques (Carlson et al., 1994), which involved “hanging out” in cocaine using areas (e.g., motels and shelters), talking to community members about local cocaine use, establishing rapport with key informants, and meeting with treatment providers. Referral coupons were given to study seeds (i.e., participants who completed the semi-structured interview), and participants could receive $10 for each referral who completed an interview (to a maximum of three referrals).

Substance-Use Life History Interviews

Substance-use life histories with 51 African American current cocaine users were conducted by a medical anthropologist and medical sociologist (the first and last authors) who are trained extensively in conducting qualitative, in-depth interviews. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was used to elicit information on participants’ 1) perceptions of substance use in their communities; 2) cocaine use history; 3) attempts to cut down or stop cocaine use; 4) treatment experiences; 5) knowledge of formal treatment programs; 6) perceptions of treatment; 7) perceived need for treatment; and 8) substance abuse and HIV treatment preferences. Interviews, which lasted from 60 to 180 minutes (average = 90 minutes), were held in a private location inside study field offices at each of the rural counties or on the UAMS campus in Pulaski County. Participants received $60, ($50 plus $10 for travel expenses), for their participation in the study.

Fifty-one total participants between the ages of 18 to 61 (average 36.1) years completed the qualitative interviews. Men and women were nearly equally represented, and demonstrated similar cocaine-use patterns. The urban-rural split was also similar, though 26 participants were from one of the two rural counties and 25 were from the single urban county. The majority (43.4%) smoked crack cocaine; 35.2% snorted powder cocaine; 15.6% smoked and snorted cocaine; and, 5.8% snorted and swallowed cocaine. Most (56.9%) participants had accessed formal substance use treatment (e.g., 30-day residential treatment center) and/or participated in self-help recovery groups such as AA and NA (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of African American Cocaine Users in the Arkansas Delta

| Qualitative sample (n = 51) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Rural n = 26 (%) | Urban n = 25 (%) | Total n or mean (%) |

| Male | 13 (50.0) | 14 (56.0) | 27 (52.9) |

| Female | 13 (50.0) | 11 (44.0) | 24 (47.1) |

| Age | |||

| < 30 years | 12 (46.2) | 9 (36.0) | 21 (41.1) |

| ≥ 30 years | 14 (53.8) | 16 (64.0) | 30 (58.9) |

| Mean age | 34.9 | 37.3 | 36.1 |

| Cocaine use patterns | |||

| Smoke crack | 7 (26.9) | 15 (60.0) | 22 (43.5) |

| Snort | 12 (46.2) | 6 (24.0) | 18 (35.1) |

| Smoke/snort | 4 (15.4) | 4 (16.0) | 8 (15.7) |

| Snort/swallow | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.5) |

| Treatment/self-help | 15 (57.7) | 14 (56.0) | 29 (56.9) |

Analysis

After each interview, the recorded conversation was professionally transcribed, then imported into a qualitative data analysis software program (MAXQDA; VERBI Software, 2012). A blended deductive and inductive approach was used to analyze the qualitative data (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007). Two qualitative researchers (the first and last authors) used structural coding to identify all text linked to the interview guide, and line-by-line reading to identify emergent themes (Bernard & Ryan, 2010). A detailed codebook was developed, and the researchers independently applied the coding schema to identical units of analysis to assess inter-coder agreement (MacQueen, McLellan, Kay, & Milstein, 1998). Codes were discussed and revised until an acceptable inter-coder reliability of 80% was reached (Bernard, 2002). During the second phase of coding, the first author used axial coding (i.e., constant comparison) to better understand the relationships between themes, and began comparing and contrasting the concepts and the participants’ discussions to further define categories and their dimensions (Strauss, Corbin, & Others, 1990).

Findings

Nearly three-quarters of the participants (72%) reported at least one attempt in their lifetimes to reduce or quit cocaine use. Table 2 shows participants’ narratives to illustrate the motivational effects of social role expectations, feeling tired of using, and criminal justice involvement in changing cocaine use patterns. Most participants cited obligations to others (e.g., caretaker) and personal and social responsibility as the primary factors motivating them to reduce or quit cocaine use. Others discussed the negative consequences of drug-using lifestyles (e.g., instability, undignified behaviors, and poor health) as motivating factors. For some, involvement in the criminal justice system (e.g., incarceration including jail and prison sentences or time in juvenile detention, and/or probation) deterred participants from using and helped them reduce and/or quit cocaine use.

Table 2.

Narrative themes from qualitative interviews.

| Theme | Speaker | Narrative | Substance Use History |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quit or reduced cocaine use | |||

| Tired of Using | 56-year-old woman with 20-year-history of crack and powder cocaine use | I was just tired, just tired of waking up looking in my pocket, was nothing but lint: waking sometimes, outside on the street 'cause I had nowhere to sleep. . . . Having to sell your body to get that shit [cocaine]. I just got tired of it and couldn't do that shit no more. | Quit for more than two years |

| 25-year-old man with history of snorting power cocaine | I was having nose bleeds and stuff. I'd just be sitting there, I could be sitting at the dinner table and my nose would start bleeding. That's kind of embarrassing. [When asked if he was concerned about his health, he replied]. Yeah, I still think about that to this day. I don't want to die of a heart attack, 'cause I mean using cocaine, I don't want to be messed up in the head when I get old. . . 'Cause I know it's causing damage to my brain. | Cyclic pattern of reducing use and quitting | |

| 51-year-old man with 25-year-history of power and crack cocaine use | I can say that one of the things that helped me this last couple of months was the quality of the cocaine is just bad. That was another reason why I stopped. . . . Me being broke and the quality of the cocaine was just terrible. It wasn't getting me high no more. It was cut too bad. It was like it was half cocaine and half something else, and I just got tired of wasting my money on nothing. | Quit because of poor quality of cocaine | |

| Social role expectations | A 32-year-old woman with 10-year history of powder cocaine use | The only reason I did cut down was for the kids and those were my main reasons. I have 4 boys and 1 girl, and the only times I didn't get high was when I was pregnant with them. . . . Then my mom always having to take my kids because I was in trouble or something was going on and happening. It was just like I really need to cut down because if I don't I keep getting myself into these troubling situations that one day I'm not going to be able to get myself out of. And maybe will never see my kids again. | Quit snorting cocaine |

| 23-year-old woman with history of powder cocaine use | I wouldn't want to hurt my Momma to know that I do the cocaine. That would kill her, not just hurt my family period. | Reduced use | |

| 46-year-old woman with history of snorting powder cocaine and smoking crack cocaine | I did stop for like, I want to say, a couple of weeks, 'cause my daughter went to jail. I had my grandson. | Quit for a couple of weeks to fulfill obligations as primary caregiver | |

| 29-year-old man with history of smoking crack cocaine | I cut it back one [time] she wasn't going to continue to put up with it. 'Be with me and our child's on the way'. So I pulled back for her sake . . . | Reduced use to be a better partner and father | |

| 25-year-old man with history of snorting powder cocaine | Every month I got bills. . . So every month I go through a process where I know I can't smoke and snort this much this week or I got to spend money on bills. . . business always comes before pleasure. | Reduced use to be financially responsible | |

| 34-year-old man with history of smoking crack cocaine and snorting powder cocaine | I tried to stop. I tried my hardest because I wanted a job. | Quit for employment purposes | |

| Incarceration | 29-year-old man who served sentences in jail and prison | One reason I cut down was I got incarcerated a couple of times. And when you're incarcerated for a year or something like that, it really helps you to pull back on it. | Reduced and stopped use due to incarceration |

| 43-year-old man who served a nine-month sentence in the county jail and nine-month sentence in prison | The cravings kind of went down because you really don't want to mess with it [cocaine] in the prison because if you get caught that's more time. | Reduced use due to fear | |

| 22-year-old urban woman sentenced to two years in juvenile incarceration for selling cocaine | It [incarceration] made me stop it [using cocaine] at the time. I didn't have no access to it, so I didn't have no other choice but to stop. | Reduced use because had no access to cocaine | |

| 25-year-old man with 27-month prison sentence | I know that cocaine get out of your system in three days. Say, well let me snort this right here and go on and get the high that I need, that I want. And, you know, three days later it's gone out of my system, parole officer never know about it. . . . I'm clean if he [parole officer] asked me to piss in a [cup]. | Quit during prison sentence; controlled user during parole |

Social role expectations

Social role expectations (e.g., “I wanted a job.”) and participants’ desires to be better parents or caregivers (e.g., “I cut down for the kids.”) and responsible persons (e.g., “I got to spend money on bills.”) were commonly cited as reasons for reducing or quitting cocaine use. Several women discussed quitting cocaine use during pregnancy, including seeking support from partners and their family to maintain sobriety. Others talked about reducing use or quitting to prevent harming their children, to become more present in their children's lives, and to prevent hurting loved ones. For these participants, their obligation to others (e.g., children, parents, and family members) helped them reduce use or quit, however temporarily. Participants, including men and women, also talked about wanting to be responsible persons who adhere to social expectations, indicating that financial responsibilities such as “spend[ing] money on bills,” basic needs (e.g., food), or their family rather than on drugs as well as seeking employment motivated them to reduce use or quit cocaine.

Tired of using

Participants frequently discussed feeling tired of using drugs and the drug-using lifestyle (e.g., living an unstable life and engaging in behaviors such as robbing and/or having sex in exchange for drugs to support substance use). Participants discussed being tired of cocaine use effects on their physical and mental health (e.g., feeling weak, having little energy, having frequent nose-bleeds, and craving cocaine and then crashing) as reasons for reducing or quitting cocaine use. In some cases, being tired of living the drug-using “lifestyle” (e.g., hustling to buy drugs, avoiding police or dangerous situations) resulted in reduced use (e.g., cutting back from daily to weekend use), whereas others quit cocaine use for significant amounts of time (e.g., two years).

Criminal Justice Involvement

Several participants explained that involvement in the criminal justice system (e.g., incarceration, time in a juvenile correctional facility and treatment center, and random urine tests due to parole, probation, or monitoring by Child Protective Services) influenced changes in their cocaine use. Several stated incarceration forced them to quit cocaine use because they had no access to alcohol or drugs. Others recounted stories of cocaine access while incarcerated, but said fear of extended incarceration motivated them to abstain. Similarly, participants on probation talked about controlling their cocaine use to prevent “dirty urine,” minimizing the risk of breaking their probation.

Accessing Capital to Reduce and Quit Cocaine Use

Most participants accessed substance use treatment programs or self-help groups at some point in their lives. They also reported attendance helped them to quit or reduce cocaine use, at least temporarily, during their substance use history. But participants were clear that “rehab” was not necessarily “the answer.” Over a third (37.2%) discussed reducing use or quitting “cold turkey” on their own without formal treatment; however, for these participants (and others) access to social, economic, and/or cultural capital facilitated reduction in cocaine use and helped maintain sobriety. Table 3 outlines participants’ narratives, revealing the types of capital accessed through treatment or self-help groups, abstinence supporting networks, engagement in pro-social activities, and religious and spiritual practices.

Table 3.

Narrative themes in discussions of Recovery Capital from qualitative interviews.

| Theme | Speaker | Narrative | Recovery capital accessed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment or self-help groups | 48-year-old man with history of smoking crack cocaine; quit using for several years | I had a peace of mind [in drug treatment]. I was isolated with people doing the same thing I'm doing. Wasn't nobody passing no drugs, wasn't no alcohol, and they would let us go to church on Sundays and we had Sunday classes and even if you didn't want to go to church, whatever your higher power was you did that. |

Social (non-drug using social networks) Cultural (substance use education; religious classes) |

| Abstinence-supporting networks | 30-year-old man reduced cocaine use | They said if you want to wean yourself, you gotta take steps. First step, quit spending your money on it. Quit hanging around it. Second step, find you a job. Third step, don't do it no more. Fourth step, you off of it. |

Social (role models; non-drug using social network) Economic (employment) |

| A 26-year-old man reduced cocaine use | When I'm not using, they [his family] can see a change in me. A dramatic change as they say. That would make me feel good. That will drive me to try to do better, because it could have been worser. I could have [been] dead. I could have been in prison for the rest of my life. | Social (non-drug using family network) | |

| 32-year-old woman reduced and quit use during pregnancy | I just started day by day, real good support systems as far as the kids' fathers were concerned. Just trying to make sure I stayed [clean] . . . 'cause I have other illnesses [depression] as well...so just trying to make sure that I didn't get high and then have those illnesses on top of that and make the baby sick on top of that. They [kids' fathers] were really there and good support systems. | Social (supportive partners and family; obligation to be a conventional mother) | |

| Pro-social activities | 42-year-old urban woman significantly reduced use within past five years | I started going to CA [cocaine anonymous] meetings, trying to be around people that didn't use. Because I knew if I went around people that used, I was gonna use. . . I knew if I went around people that used, I was gonna use. . . Then I learned to just start doing things that normally [I] wouldn't do when I was using, like go to the movies, go out to eat, stuff like that, or even go to church. |

Cultural (CA knowledge; conventional and “normal” activities) Social (non-drug using social network) |

| 52-year-old man with history of smoking crack cocaine; quit for over six years | I moved to Dallas . . . I quit smoking. I had to change my life. | Social (non-drug using context) | |

| 46-year-old urban man reduced use | I say going to church with my friend that's a pastor now, and going to eat, doing the things that you supposed to do. |

Cultural (religious knowledge; conventional activities) Social (non-drug using friendship) |

|

| Religion and spirituality | 20-year-old woman; quit use during and after pregnancy | I put it in my head. And I prayed. Got on my knees to God. I don't need it. . . I got a baby. I have somebody else to look after; another person to care for, a whole 'nother life. | Social (divine support) |

| 51-year-old man with 25-year history of smoking crack cocaine; reduced use from daily to occasional use | Church, thinking about how God has spared me and give me a lot of chances and basically that's it. |

Cultural (religious knowledge) Social (divine support) |

|

| 41-year-old woman with 16-year history of crack cocaine use; quit using for four months | I asked the Lord to please do this for me, to take this taste [for drugs] away from me. | Social (divine support) |

Abstinence-supporting networks

Positive support systems, which encouraged participants to interact with non-drug–using friends, family members, and persons in recovery, were instrumental in participants’ ability to reduce cocaine use and/or achieve temporary recovery outside of rehab, or as several participants explained “on my own.” Many participants discussed reducing use or quitting by changing social groups (e.g., “Don't go around the same people”), staying close to home, re-locating, and spending time with non-drug using friends. Others expressed the critical influence of recovering community members in reducing use and recovery, and/or shared stories of close relatives, friends, and neighbors who “weaned themself off.” Recovering community members served as role models, providing strategies to reduce and quit cocaine use (e.g., removing oneself from drug-using networks, not purchasing cocaine, and finding employment). Non-drug using family members and partners played critical roles in bolstering self-esteem and encouraging cocaine use reduction and abstinence, especially during critical life stages (e.g., pregnancy).

Pro-social lives and activities

Participation in conventional, non-drug–using activities such as church, leisure-time activities, and living a “normal life” were also critical to reducing and maintaining changes in cocaine use. Many participants discussed engaging in activities they did not commonly do while using (e.g., going to the movies or eating out). Some completely removed themselves from drug-using networks, relocating to new places or moving-in with family to re-establish their lives and daily activities. Additionally, attending church and participating in faith-based activities, including Bible studies and choir, legitimized decisions to abstain from use and occupied time. Non-drug using social networks allowed participants to surround themselves with non-cocaine users, develop positive social support, and speak with ex-users, friends and family, and clergy about life stress and problems linked to cocaine use.

Religion and spirituality

Prayer, reading the Bible, and having faith in God and the divine were also important to participants’ experiences of reducing or quitting cocaine use. Participants discussed praying to God or the Lord when they craved cocaine, seeking guidance and encouragement through their faith. For some, prayer strengthened their relationship with the divine as well as their inner selves, ultimately giving them confidence and strength to resist temptation (e.g., free drugs) or cravings. Others believed divine intervention (e.g., God's ability to take away drug cravings) helped them reduce or quit cocaine use, with several participants citing they handed over their addiction to God believing that He would intervene and “take it away” (Anonymous, 2014).

Discussion

Historically a taboo topic in addiction treatment, recovery without treatment (also called natural recovery) questions the disease model of addiction and the underlying assumption that self-recovery is not possible (Burman, 1997; Chiauzzi & Liljegren, 1993). The majority of participants in this study (i.e., current non-intravenous cocaine users) described at least one lifetime attempt to reduce or quit cocaine use. More than half of the participants attended formal treatment programs (e.g., AA, NA) and/or self-help groups using the AA 12-step program (Anonymous Press, 2009). Treatment and self-help groups helped participants find supportive, non-drug using communities, but these formal services were not necessarily key in reducing or quitting cocaine use. Our findings reinforce that controlled use and recovery without treatment, albeit temporary in this sample, is a common and possibly natural progression of sustained cocaine use. In-depth analysis of participants’ substance-use life histories revealed that recovery without treatment largely coincided with lifestyle changes and shifting social relationships.

Participants sought out non-drug using social networks through their faith community, AA, or family and close friends; these social relationships facilitated engaging in pro-social lives and accessing resources (e.g., employment, religious knowledge, and positive support) needed to initiate cocaine use reduction and sobriety maintenance. Leading a pro-social life and adhering to conventional social roles, expectations, and dominant values (e.g., steady employment and stable living) offers recovering users capital to re-engage with “institutional life” such as work and religion (Dawson et al., 2006; Granfield & Cloud, 2001, p. 1554; Walters, 2000). Other participants found “leaving the scene” (i.e., a shift from drug-using networks to non-drug using networks and activities) was critical to recovery among persons in resource-poor communities where illicit drugs are increasingly available and there are barriers to accessing substance use services (Dickson-Gomez et al., 2011, p. 434). Our work corraborates previous research demonstrating that re-establishing abstinence-supporting networks and re-engaging in institutional life increases access to recovery capital which, among this sample of African Americans, involved positive social relationships, employment, religious and drug-use education, and divine support (see Table 3). Recovery capital allowed participants to lead healthier lifestyles, participate in leisure time activities, and assume valued social roles (Laudet & White, 2008).

Reliance on social support as gained through faith communities rather than formal treatment is particularly pronounced among racial and ethnic minorities in disadvantaged social contexts. Perron et al. (2009) found Whites accessed professional services (e.g., drug treatment programs) more often than African Americans who commonly participated in 12-step programs and relied on clergy to abstain from alcohol use. Addiction treatment has historically employed an acute care model involving brief individual-focused interventions, which may not be an ideal approach in minority communities. Rather, a broader perspective that situates the etiology of addiction in historical and cultural contexts (e.g., racism and disempowerment), draws on community resources and social relationships (e.g., kinship networks), and incorporates religious values (e.g., hope) in recovery services is likely a more appropriate recovery model (White & Sanders, 2004). Research shows that cocaine-using African Americans in the South want community-based programs involving others in the African American community, including ex-users, family, and churches (Brown et al., 2004).

Because African Americans, especially those in rural areas, often face personal, cultural, and structural barriers to accessing formal treatment programs, reducing or quitting cocaine use without formal treatment might be a more feasible alternative and may encourage reliance on existing networks of support. However, it is important to reiterate that structural and social inequalities, including differential access to quality education, employment and career opportunities, adequate housing, and healthcare, have greatly impacted the lives of African Americans in the Mississippi Delta (Rogers, 2006). Limited access to valued resources such as education, employment, and healthcare services signify what Bourdieu (1977) has identified as the daily struggle for capital or power. Therefore, because the social networks of African Americans in the South tend to be comprised of blood relatives and extended kin rather than persons of diverse social and economic backgrounds (Goldbarg & Brown, 2009), their access to recovery capital may be limited.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. Our sample included African American cocaine users who were actively using and not in treatment; therefore, our findings do not reflect the experiences and perspectives of persons in sustained recovery. Future work should aim to understand the role of recovery capital in long-term, continued sobriety from cocaine use. Furthermore, we did not collect systematic data on participants’ social networks nor resources embedded within them. Despite these limitations, the narratives of African Americans in this paper demonstrate that individuals’ abilities to access resources through their social ties influence substance use outcomes (i.e., reduced use and sobriety) in that those connected to network members with access to resources (e.g., jobs, housing, and social support) reduced cocaine use or achieved temporary sobriety. Studies using systematic methods to analyze social networks, such as social network analysis, are needed to fully understand social network influence in substance use outcomes and the role of recovery capital in mitigating reduced use and recovery (Valente, Gallaher, & Mouttapa, 2004).

Conclusions

“Natural” recovery from illicit drugs through changes in social networks is not well understood and represents a growing area of inquiry in drug abuse research (Williams & Latkin, 2007). African American substance users in the South would likely benefit from community-based substance use programs involving others in the African American community, including former users, family, and churches. Questions remain about the role of social networks (positive or negative) in cocaine use outcomes in this population, and how to engage recovering users, family, and the faith community in recovery efforts. Answering these questions requires investigating the social networks characteristic of both active and recovering cocaine users to compare and contrast network members (e.g., drug users, and abstinence supporters) and identify the resources available in these diverse social networks. Furthermore, studies using social network analysis are needed to provide critical insights regarding the development of network-level interventions (e.g., interventions that encourage African Americans to remove themselves from substance using social networks), and how best to implement them (e.g., work with network members who have access to resources) within low-income, high-risk communities.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA026837 to Dr. Tyrone Borders. At the time of the work Ann Cheney was a Scholar with the HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse, and Trauma Training Program (HA-STTP), at the University of California, Los Angeles; supported through an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R25 DA035692).

Glossary

- Arkansas Mississippi Delta region

A region along the eastern border of Arkansas next to the Mississippi River; one of the most impoverished areas of the United States; has a predominantly African American population

- Substance Use (SU)

The consumption of alcohol and/or drugs

- Recovery without treatment

Initiating and maintaining the recovery process without accessing formal drug treatment services or self-help 12-step groups; also referred to as “natural recovery,” “spontaneous remission,” “maturing out,” “unassisted recovery,” and “self-change.”

- Capital

Valued resources including social support (social capital), money (economic capital), and education (cultural capital); lifestyles, values, and norms of particular social groups shape perceptions of valued resources; capital access is constrained by social position and institutional power structures.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S39–45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgov.com. [07/28/2015];Delta Regional Authority. 2015 2015, 2015, from http://www.allgov.com/departments/independent-agencies/delta-regional-authority?agencyid=7307.

- Anonymous Press, T. Alcoholics Anonymous First Edition Reprint: By the Anonymous Press. The Anonymous Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration (Cartographer) Delta Region. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.dfa.arkansas.gov/Pages/Delta.aspx.

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology : qualitative and quantitative methods. AltaMira Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing qualitative data : systematic approaches. SAGE; Los Angeles [Calif.]: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Booth BM, Leukefeld C, Falck R, Wang J, Carlson R. Correlates of rural methamphetamine and cocaine users: results from a multistate community study. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(4):493–501. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Outline of a Theory of Practice (Vol. 16) Cambridge university press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Hill MA, Giroux SA. “A 28-Day Program Ain't Helping the Crack Smoker”—Perceptions of Effective Drug Abuse Prevention Interventions by North Central Florida African Americans Who Use Cocaine. J. Rural Health. 2004;20(3):286–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Trujillo TH. “Bottoming out?” Among rural African American women who use cocaine. J Rural Health. 2003;19(4):441–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman S. The challenge of sobriety: natural recovery without treatment and self-help groups. J. Subst. Abuse. 1997;9:41–61. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90005-5. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RG, Wang JC, Siegal HA, Falck RS, Guo J. An Ethnographic Approach to Targeted Sampling - Problems and Solutions in Aids-Prevention Research among Injection-Drug and Crack-Cocaine Users. Human Organization. 1994;53(3):279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney AM, Curran GM, Booth BM, Sullivan S, Stewart KE, Borders TF. The religious and spiritual dimensions of cutting down and stopping cocaine use: A qualitative exploration among African Americans in the south. Journal of Drug Issues. 2014;41(1):94–113. doi: 10.1177/0022042613491108. doi: 10.1177/0022042613491108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiauzzi EJ, Liljegren S. Taboo topics in addiction treatment. An empirical review of clinical folklore. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1993;10(3):303–316. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90079-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2-3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated Appropriations Act. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda (Maryland): 2011. pp. 2094–2103. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: the impact of transitional life events. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(2):195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson-Gomez J, Bodnar G, Guevara CE, Rodriguez K, De Mendoza LR, Corbett AM. With God's help i can do it: crack users? Formal and informal recovery experiences in El Salvador. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(4):426–439. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.495762. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.495762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E. Impact of drugs on family life and kin networks in the inner-city African-American single parent household. Drugs, crime, and social isolation: Barriers to urban opportunity. 1992:181–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, Golub A, Johnson BD. The Severely-Distressed African American Family in the Crack Era: Empowerment is not Enough. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2006;33(1):115–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix H, Stewart MK. Health Status in the Mississippi River Delta Region. South Med J. 2005;98(2):149. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000145304.68009.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A. The pastoral clinic: Addiction and dispossession along the Rio Grande. Univ of California Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goldbarg RN, Brown EJ. Gender, personal networks, and drug use among rural African Americans. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2009;30(1):41–54. doi: 10.2190/IQ.30.1.d. doi: 10.2190/IQ.30.1.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R, Cloud W. Social context and “natural recovery”: The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use & Misuse. 2001;36(11):1543–1570. doi: 10.1081/ja-100106963. doi: Doi 10.1081/Ja-100106963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations. Soc. Probl. 1997;44(2):174–199. doi: 10.2307/3096941. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD, Semaan S, Broadhead RS, Hughes JJ. Extensions of Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Injection Drug Users Aged 18–25. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(1):55–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1014528612685. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge DR, Marsiglia FF, Nieri T. Religion and Substance Use among Youths of Mexican Heritage: A Social Capital Perspective. Social Work Research. 2011;35(3):137–146. doi: 10.1093/swr/35.3.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann H, Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Continuities and changes in self-change research. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1510–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02770.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Morgen K, White WL. The role of social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning and affiliation with 12-step fellowships in quality of life satisfaction among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 2006;24(1-2):33–73. doi: 10.1300/J020v24n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, White WL. Recovery capital as prospective predictor of sustained recovery, life satisfaction, and stress among former poly-substance users. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(1):27–54. doi: 10.1080/10826080701681473. doi: 10.1080/10826080701681473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Hasin DS, de Los Cobos JP, Pines A, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C. Probability and predictors of remission from life-time nicotine, alcohol, cannabis or cocaine dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction. 2011;106(3):657–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03194.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen K, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis. Field Methods. 1998;10(2):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Page JB, Singer M. Comprehending drug use: Ethnographic research at the social margins. Rutgers University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perron BE, Mowbray OP, Glass JE, Delva J, Vaughn MG, Howard MO. Differences in service utilization and barriers among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites with drug use disorders. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-3. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers KL. Life and death in the Delta : African American narratives of violence, resilience, and social change. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rural Development, Agriculture, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Saikku M. Bioregional Approach to Southern History: The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta. Southern Spaces. 2010 Jan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton RL, Carlson RG, Leukefeld CG, Booth BM. Barriers to formal drug abuse treatment in the rural south: a preliminary ethnographic assessment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(2):121–129. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400621. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Ellingstad TP, Sobell MB. Natural recovery from alcohol and drug problems: methodological review of the research with suggestions for future directions. Addiction. 2000;95(5):749–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research. Vol. 15. Sage; Newbury Park, CA.: 1990. Others. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud HB. [07 28 2015];Mississippi Alluvial Plain. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. 2014 01/03/2014, 2015, from http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=444.

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US. [07/28/2015];2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. 2010 2015, from http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html.

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service [July 20, 2015];County-level Datasets -- Percent of total people in poverty, Arkansas (Dataset) 2013 http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-level-data-sets/poverty.aspx?reportPath=/State_Fact_Sheets/PovertyReport&stat_year=2013&stat_type=0&fips_st=05.

- Valdez A, Neaigus A, Kaplan CD. The Influence of Family and Peer Risk Networks on Drug Use Practices and Other Risks among Mexican American Noninjecting Heroin Users. J Contemp Ethnogr. 2008;37(1):79–107. doi: 10.1177/0891241607309476. doi: 10.1177/0891241607309476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Gallaher P, Mouttapa M. Using social networks to understand and prevent substance use: a transdisciplinary perspective. Subst. Use Misuse. 2004;39(10-12):1685–1712. doi: 10.1081/ja-200033210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software . MAXQDA, software for qualitative data analysis, 1989-2012. Sozialforschung GmbH; Berlin, Germany: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walters GD. Spontaneous remission from alcohol, tobacco, and other drug abuse: seeking quantitative answers to qualitative questions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26(3):443–460. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W, Sanders M. [January, 2, 2005];Recovery management and people of color. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Williams CT, Latkin CA. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, personal network attributes, and use of heroin and cocaine. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6 Suppl):S203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.006. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]