Abstract

Problem addressed

In Canada, there are few health promotion programs for men, particularly programs focused on indigenous and other men marginalized by social and structural inequities.

Objective of program

To build solidarity and brotherhood among vulnerable men; to promote health through education, dialogue, and health screening clinics; and to help men regain a sense of pride and fulfilment in their lives.

Program description

The DUDES Club was established in 2010 as a community-based health promotion program for indigenous men in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood of Vancouver, BC. Between August 2014 and May 2015, 150 men completed an evaluation survey developed using a logic model approach. Responses were analyzed based on the 4 dimensions of the indigenous medicine wheel (mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual). Evaluation results demonstrated high participant satisfaction and positive outcomes across all 4 dimensions of health and well-being: 90.6% of respondents indicated that the DUDES Club program improved their quality of life. Participants who attended meetings more often experienced greater physical, mental, and social benefits (P < .05).

Conclusion

Findings indicate that this innovative model is effective in promoting the well-being of mainly indigenous men through culturally safe services in an urban community.

Résumé

Problème à l’étude

Au Canada, il existe peu de programmes pour promouvoir la santé des hommes, notamment des programmes à l’intention des autochtones et d’autres hommes qui sont marginalisés en raison d’injustices sociales et structurelles.

Objectif du programme

Développer un esprit de solidarité et de fraternité chez des hommes vulnérables; promouvoir la santé par l’éducation, et le dialogue, et par des cliniques de dépistage des problèmes de santé; et aider des hommes à retrouver un sens de fierté et d’accomplissement dans leur vie.

Description du programme

Le DUDES Club a été créé en 2010 sous la forme d’un programme communautaire pour promouvoir la santé des hommes autochtones du quartier Downtown Eastside de Vancouver, en Colombie-Britannique. Entre août 2014 et mai 2015, 150 hommes ont répondu à un questionnaire d’évaluation élaboré à l’aide d’un modèle logique. Les réponses ont été analysées en fonction des 4 dimensions de la roue de la médecine autochtone (mentale, physique, émotionnelle et spirituelle). Les résultats de cette évaluation ont révélé un haut niveau de satisfaction chez les participants et des issues positives dans les quatre dimensions de la santé et du bien-être : 90,6 % des répondants ont indiqué que le programme du DUDES Club avait amélioré leur qualité de vie. Les plus assidus aux réunions en avaient retiré les meilleurs avantages sur les plans physique, mental et social (P < ,05).

Conclusion

Ces observations indiquent qu’un tel modèle innovateur est un moyen efficace de promouvoir le bien-être chez les hommes, principalement chez les autochtones, au moyen de services culturellement sécuritaires au sein d’une communauté urbaine.

Compared with the general population, indigenous*1 peoples in Canada continue to experience considerably higher rates of mortality, morbidity, and preventable diseases.2,3 When it comes to mental health in particular, indigenous men are at greater risk of depression and suicide and suffer a disproportionate burden of other mental health issues compared with the general population.4–7 Further, men are generally less likely than women are to seek help with health issues and they face many barriers when accessing appropriate mental health services.8–11 As a result, men suffer in silence far too often.

Increasingly, it is recognized that persistent health and social disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous Canadians must be understood within the context of Canada’s colonial history (eg, residential schooling and the Sixties Scoop) and ongoing inequitable social determinants of health (eg, poverty, homelessness, systemic stigma, and discrimination).12–19

Despite this, there is a paucity of research on Canadian indigenous men’s mental health and the factors affecting access to and effectiveness of available services and supports. Research from Australia on Men’s Sheds, a nationwide community-based men’s health campaign, reveals there are many important factors to consider when implementing successful men’s health promotion programs.20–23 Furthermore, research indicates the importance of men’s-only spaces for health engagement, as outlined in an accompanying commentary in this issue (page 463).24 This article reports on the findings of a rigorous evaluation of the DUDES Club, a health promotion program designed to address the health needs of men, most of whom are indigenous, living in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) community of Vancouver, BC.

Program objective

The DUDES Club was established in 2010 by men living in the DTES community who believed there was a critical gap in men’s health services. This community is among one of the most adversely affected by the social determinants of health in Canada.25 As the DUDES Club slowly evolved, grassroots members developed 3 overarching objectives: to build solidarity and brotherhood between members; to promote men’s health through education, dialogue, and health screening clinics; and to enable men to regain a sense of pride and fulfilment in their lives. The DUDES Club is committed to carrying out its stated objectives in an inclusive, nonjudgmental, and holistic way. In fact, the DUDES Club is accepting of the full spectrum of the men’s community in the DTES (gay, transgender, 2-spirited, etc). The motto “Leave your armour at the door” provides an important foundation, as meetings are a safe place for men to shed their defences, be vulnerable, and open up to one another. Men have referred to meetings as a “sanctuary” to get away from the harsh realities of life in the DTES. Regardless of their current mental or physical state, members are welcome as long as they remain respectful and follow the code of conduct.

Program description

The DUDES Club meetings are held every 2 weeks in a drop-in space at the Vancouver Native Health Society, where men feel safe and other successful peer-support programs operate. On average, the club hosts 50 to 60 men with a core of volunteers who direct the activities and vision of the project. Volunteers receive modest compensation for their work, which can include cooking, serving, cleaning, facilitating activities, and planning meetings. As a large percentage of the members are indigenous, the club strives to create cultural safety by including indigenous perspectives such as medicine wheel teachings, regular participation of elders, and bringing in health care professionals who provide a culturally safe context for indigenous peoples. The meetings routinely start with an opening prayer led by a local Musqueam elder. The men then socialize and participate in various casual activities, followed by a hot meal. After the meal, an interactive health discussion is facilitated by a health care worker (mostly physicians, but occasionally a nurse or social worker), which allows men to ask questions about their health and to improve their health literacy and peer-support skills. Meetings always close with a prayer led by the DUDES Club elder. The DUDES Club represents somewhat of a paradigm shift in health care services to create a safe place where men can proactively address their health needs in a nonthreatening, inclusive environment. Thanks to grant support from the Movember Foundation, our research team has supported the successful establishment of 3 pilot sites in northern British Columbia: Prince George, Smithers, and Moricetown (First Nations reserve). Program evaluation is ongoing in those sites.

Program evaluation

Drawing on a mixed-methods design to assess the effectiveness of the program, our research team administered a program evaluation survey and conducted a series of ethnographic semistructured focus group interviews with DUDES Club members. Findings from our qualitative analysis, while rich in detail about themes such as trust and safety, are preliminary and will be presented elsewhere. From August 2014 to May 2015, 150 men, selected by convenience sampling, completed an evaluation survey under the supervision of our research assistant (to ensure comprehension and completion). Considering the transient nature of the DTES community, we believed that this sample size would provide robust data to capture the diversity of DUDES Club members’ perspectives. We were unable to find validated evaluation tools applicable to our program context; thus we generated our own evaluation survey, which was developed using a logic model approach.26 This survey was developed with critical input from a community advisory team made up of DUDES Club members, providers, community members, and elders. Indeed, the advisory team members’ experiential knowledge of the DUDES Club was essential in guiding how the research team theorized the plausible linkages among the program’s activity inputs, outputs, and outcomes. This process allowed the research team to capture relevant and valid success indicators and develop matching survey questions. The resulting questionnaire was pilot-tested with key DUDES Club members before being approved for use. Its final version consisted of 5 pages, covering key demographic factors and evaluation parameters that included both Likert scale and open-ended questions. The research team developed meaningful clusters from the survey questions to allow for more refined statistical analysis and relevant findings for program improvement. These clusters were based on the 4 dimensions of the medicine wheel (mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual) to honour indigenous approaches to health. Statistical analysis of survey variables was done using t tests and ANOVA (analysis of variance).

Results

Detailed demographic characteristics of members are shown in Table 1. Overall, DUDES Club members are mostly middle-aged indigenous men who are often living in unstable housing, unemployed, and estranged from their families. The demographic composition of the DTES community is well documented in the literature,18,25 which is why we only sought to record demographic characteristics that DUDES Club members thought would be meaningful to our program evaluation.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of DUDES Club members

| CHARACTERISTICS | VALUE |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| • Mean, y | 46.8 |

| • ≥ 40 y, % | 78.0 |

| • Range, y | 22–68 |

| Ethnicity, % | |

| • Indigenous | 63.3 |

| • White | 24.0 |

| • Other | 12.7 |

| Unstable housing, %* | 64.7 |

| Residence, % | |

| • Lives in DTES | 80.8 |

| • Has lived in DTES > 5 y | 60.6 |

| Unemployed in past 6 mo, % | 56.0 |

| Family status, % | |

| • Single | 73.8 |

| • Have children | 59.1 |

| • Living with children | 4.5 |

DTES—Downtown Eastside.

Unstable housing includes single-room occupancy hotels, shelters, and homelessness.

Univariate analysis demonstrated that the program was highly rated overall (Table 2). To stratify the data, responses were analyzed in 2 groups: those rating 4 or 5 out of 5 and those rating less than 4 out of 5. Using this approach, 96.0% of the men were either satisfied or very satisfied with the program, with 90.6% of respondents indicating that the DUDES Club program improved their quality of life. In terms of the cluster analysis (Table 3), mental wellness benefits had the highest mean score of 87.2% (4.36 out of 5), while spiritual wellness had the lowest mean score at 78.0% (3.90 out of 5). The physical health cluster had a mean score of 85.2% (4.26 out of 5).

Table 2.

Program satisfaction

| ELEMENT OF PROGRAM | SCORE ≥ 4 OUT OF 5, % | SCORE < 4 OUT OF 5, % |

|---|---|---|

| Overall program satisfaction | 96.0 | 4.0 |

| Improves quality of life | 90.6 | 9.4 |

| Helpfulness of health presentations | 85.3 | 14.7 |

| Increases health confidence | 83.6 | 16.4 |

Table 3.

Overall health cluster ratings

| HEALTH BENEFITS (SAMPLE SURVEY QUESTION) | CLUSTER RATING, % |

|---|---|

| Mental wellness benefits (eg, Attending the DC improves my life quality) | 87.2 |

| Effect on spiritual wellness (eg, Attending the DC supports my spiritual well-being) | 78.0 |

| Physical health: effects on thinking and behaviour (eg, Attending the DC makes me think about my health in a more proactive way) | 85.2 |

| Social support: connectedness and social belonging (eg, Attending the DC assists me in making new relationships and friendships with other men) | 82.9 |

| Indirect mental health effects: experiences of safety, trust, comfort (eg, I am attending the DC because it is a safe space to connect and share with each other) | 84.9 |

| Direct mental health effects: resilience, positive outlook, quality of life (eg, Attending the DC helps me when I feel down or blue) | 85.3 |

| Peer support (eg, Attending the DC helps me feel supported in my health by other men in the community) | 82.6 |

DC—DUDES Club.

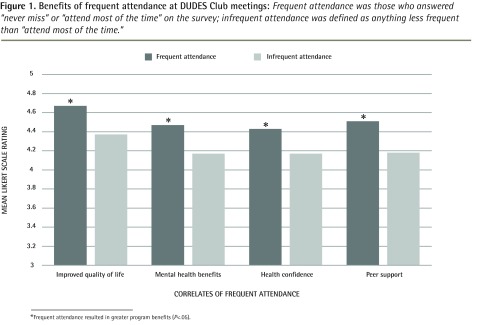

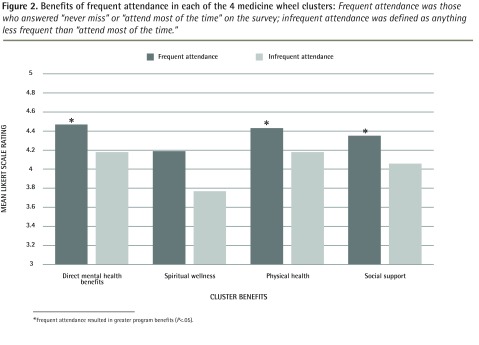

In the multivariate analysis, attendance emerged as a critical variable in our evaluation, underscoring the transience of the DTES community. Participants were asked to characterize their attendance since they first joined the DUDES Club (many men have been coming for years): 30.0% of our men identified their attendance as “never miss” or “attend most of the time,” while 30.7% attend “occasionally,” 32.7% have attended “only a few times,” and 6.7% indicated this was their “first time.” Unfortunately, we were unable to capture true attendance data owing to incomplete historical attendance records. We collapsed these 5 categories into 2 (“never miss” and “most of the time” vs “occasionally,” “only a few times,” and “first time”) in order to conduct our statistical analyses. In the absence of a control group, our program evaluation employed this approach to see if those who attended often derived more meaningful benefit from the program. We observed that men who attended more often scored higher on most survey variables, some examples of which are highlighted in Figure 1. This “dose-response” relationship was noted when comparing mean Likert scores on survey questions between the highest rating (5 out of 5) and lower rating (1 to 4 out of 5) groups. In this binary analysis, the strongest results demonstrated that for men who attend often, the DUDES Club provides a greater feeling of connectedness (P = .017) and improved quality of life (P = .017). Finally, the cluster analysis (physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of health) demonstrates this “dose-response” relationship across all clusters. However, only physical health, social health, and direct mental health benefits clusters achieved statistical significance, as shown in Figure 2. It was interesting to note that older men (≥ 40 years old) had more frequent attendance at DUDES Club meetings (P = .008).

Figure 1.

Benefits of frequent attendance at DUDES Club meetings: Frequent attendance was those who answered “never miss” or “attend most of the time” on the survey; infrequent attendance was defined as anything less frequent than “attend most of the time.”

*Frequent attendance resulted in greater program benefits (P<.05).

Figure 2.

Benefits of frequent attendance in each of the 4 medicine wheel clusters: Frequent attendance was those who answered “never miss” or “attend most of the time” on the survey; infrequent attendance was defined as anything less frequent than “attend most of the time.”

*Frequent attendance resulted in greater program benefits (P<.05).

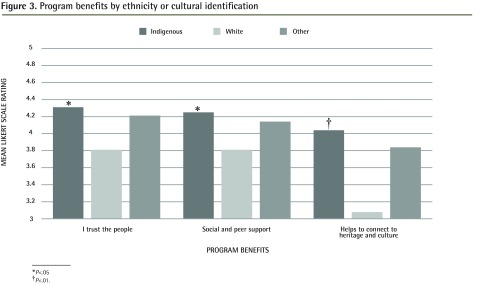

Considering that the DUDES Club is particularly focused on indigenous men and emphasizes indigenous approaches to health, we examined the influence of ethnicity and cultural identification on all variables in our evaluation survey. Figure 3 highlights salient findings where indigenous men responded more favourably to survey measures. In particular, feelings of trust (P = .037), supporting other men in their health (P = .07), and connecting with heritage and culture (P = .001) were significant outcome measures.

Figure 3.

Program benefits by ethnicity or cultural identification

*P<.05

P<.01.

Age was assessed with a cutoff of 40 years of age and older, compared with those younger than 40, and we found no noteworthy differences in survey responses. While older men attend more often, it seems our program has no additional benefit for them. Finally, we used one of our questions (How would you rate your overall health?) as an internal validation for sensitivity analysis. Men who rated higher on this question were not more likely to respond to other survey questions with a similarly high rating approach, thus minimizing the possibility of response bias.

We conducted a thematic analysis of the open-ended survey responses. The most common themes in these evaluation questions are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample open-ended evaluation survey questions and common themes in responses

| SURVEY QUESTIONS | COMMON THEMES |

|---|---|

| 13. Why do you attend the DC? | Food, friends, socializing, health information |

| 14. How does the DC compare with other groups in the DTES? | Men’s only, friendly and relaxed atmosphere, “good,” “better,” or “best” |

| 29. How could the DC be improved (give examples)? | Larger space, more frequent meetings |

DC—DUDES Club, DTES—Downtown Eastside.

Discussion

The DUDES Club addresses a critical gap in health services in the DTES community. The innovative model of engaging men in a safe space while honouring indigenous healing principles provides a unique balance of social supports and health services for a population at high risk of poor health and wellness.

As the evaluation survey findings reflect, DUDES Club members are highly marginalized by social and structural inequity (eg, poverty, homelessness). Despite these omnipresent barriers to accessing health and social services, participant satisfaction was documented across multiple aspects of the DUDES Club program. Indigenous participants in particular found increased feelings of trust, support, and connection to culture and heritage through participating in the program. This is a particularly salient finding considering the many barriers these men face when accessing health services and the reticence some have about developing therapeutic relationships.

Age of participants did not emerge as a significant variable, which is contrary to previous research indicating that older men in particular have difficulty accessing appropriate health care.27–29 As demonstrated by our DUDES Club model, older men can successfully engage in health care services when they are relevant, non-threatening, and guided with direct input from members. Further, considering the age range of our participants, older men were often able to provide guidance and mentorship to younger men in the community, further developing the peer-support elements of the program.

From an evaluation perspective, the most meaningful finding was the “dose-response” effect related to attendance. Participants who came more often rated more highly in all aspects of the evaluation clusters derived using the medicine wheel approach (ie, addressing physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional dimensions of self). Furthermore, frequent attendance led to significant effects on quality of life, mental health benefits, and health confidence (P < .05), regardless of ethnocultural background. Therefore, coming more often to DUDES Club meetings improved survey outcomes across all aspects of the indigenous medicine wheel. This “dose-response” effect can be explained through the combination of positive effects as rated by DUDES Club members and indicates that efforts to retain members will likely lead to considerable health improvements.

Thematic analysis of the open-ended questions indicate that men attend meetings because of the health information provided and that the men’s-only aspect is a unique feature of the club within DTES programming (Table 4). For these men, the club is clearly helping to fill an identified gap in community-based services.

Members attend the DUDES Club in large part to maintain and establish friendships (Table 4), which is evidence that the model successfully addresses its first pillar: to build solidarity and brotherhood among its members. As social support is an important determinant of health, these healing relationships between DUDES Club members contribute to the second pillar of health promotion.30 Further, the relaxed and friendly environment of the DUDES Club was repeatedly cited as a unique factor compared with other DTES programs (Table 4). This is important because stress is related to a series of negative health issues, especially in those made vulnerable by marginalizing social and structural forces.31 Thus, this environment is often seen to provide a “safe sanctuary” where men can find respite from the competing stresses they face and engage more meaningfully in critical health promotion services. In terms of explicit, tangible program improvements, members expressed interest in having a larger meeting space and more frequent meetings.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of this study is the lack of a validated evaluation tool for use in this population. However, through substantial collaboration with elders and community members, the survey provides meaningful results to help continually improve the program. Further, owing to the transient nature of the population, this evaluation was unable to capture responses from men no longer attending the DUDES Club, possibly resulting in an element of sampling bias. Recording and analyzing true attendance, while extremely time consuming, would have also provided the opportunity to create attendance cohorts within the study population and thus assess the longitudinal effects of the program. Our research team is considering that approach for further study.

Finally, while the use of self-report measures of health could be considered a limitation, research indicates that single-item measures of health are correlated with physician assessments of client morbidity.32 Further research could aim to use more traditional measures of health improvement such as medication adherence or the frequency and nature of and the quality of engagement with clinician visits.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, our evaluation indicates a consistently positive pattern of results across several different analyses. Specifically, it is important to note that we were able to demonstrate statistically significant differences even with high ratings across groups on multiple survey variables. These results provide promising support for the DUDES Club’s unique approach to overcoming barriers to health engagement among mostly indigenous men living in Vancouver’s DTES. The success of the DUDES Club is in large part owing to the hard work of a dedicated core group of community members and health professionals who collaborate to drive the ongoing planning and execution of meetings. Effective replication of this model would require a sustained commitment to supporting community-driven, culturally responsive programming in other settings. Family physicians are particularly well placed as community health partners to advocate for and assist in implementing innovative programs through dissemination and translation of findings such as these.33

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jonathan Berkowitz for his statistical support, Mr Bill Mussell for his expert knowledge of indigenous mental health issues, and Henry Charles for his role as Musqueam elder with the Dudes Club since 2011.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Compared with the general population, indigenous peoples in Canada continue to experience considerably higher rates of mortality, morbidity, and preventable diseases and a disproportionate burden of mental health issues. Further, men are generally less likely than women are to seek help with health issues and they face many barriers when accessing mental health services.

The DUDES Club is a community-based health promotion program largely for indigenous men in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood of Vancouver, BC, that aims to build solidarity and brotherhood among vulnerable men. Three pilot sites have also been established in northern British Columbia.

Biweekly drop-in meetings are a safe place for men to shed their defences, be vulnerable, and open up to one another, as well as to socialize and to improve their health literacy and peer-support skills. Results of an evaluation survey at the Vancouver site were overwhelmingly positive, indicating that the program improves the mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being of members.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Par rapport à la population générale, les autochtones du Canada présentent toujours un taux plus élevé de mortalité, de morbidité et de maladies évitables, et un taux disproportionné de problèmes de santé mentale. En outre, les hommes sont généralement plus susceptibles que les femmes de consulter pour des problèmes de santé mentale et ils font face à plusieurs obstacles lorsqu’ils veulent obtenir des services de santé pour ces problèmes.

Le DUDES Club (club des gars) est un programme communautaire qui veut améliorer la santé des hommes autochtones quartier du Downtown Eastside de Vancouver, et créer une solidarité et une fraternité entre des hommes vulnérables. Des programmes pilotes semblables ont été établis dans trois sites du nord de la Colombie-Britannique.

Lors de leurs réunions bihebdomadaires optionnelles, les hommes ont l’occasion de laisser tomber leurs hésitations, d’avouer leur vulnérabilité et de s’ouvrir les uns aux autres, mais aussi de socialiser et d’améliorer leurs connaissances sur la santé et leur capacité d’aider leurs semblables. Les résultats d’un questionnaire d’évaluation au site de Vancouver étaient en très grande majorité positifs, ce qui indique que le programme améliore le bien-être mental, physique, émotionnel et spirituel des membres.

Footnotes

In using the term indigenous, the authors intend the term to be inclusive of all aboriginal peoples in Canada: First Nations, Metis, and Inuit. A more extensive definition of indigenous can be found in the recently published Health and Health Care Implications of Systemic Racism on Indigenous Peoples in Canada.1

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept, design, or functioning of the program; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Indigenous Health Working Group . Health and health care implications of systemic racism on indigenous peoples in Canada. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson K, Cardwell N. Urban indigenous health: examining inequalities between indigenous and non-aboriginal populations in Canada. Can Geogr. 2012;56(1):98–116. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Susan W. The social distribution of distress and well-being in the Canadian aboriginal population living off reserve. Int Indig Policy J. 2011;2(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health Disparities Task Group of the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health and Health Security . Reducing health disparities—roles of the health sector: discussion paper. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2005. Available from: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/disparities/pdf06/disparities_discussion_paper_e.pdf. Accessed 2016 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirmayer LJ, Brass GM, Holton TL, Paul K, Simpson C, Tait CL. Suicide among aboriginal peoples in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gone JP. American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8(1):131–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127. Epub 2011 Dec 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mood Disorders Society of Canada . Quick facts: mental illness and addiction in Canada. Guelph, ON: Mood Disorders Society of Canada; 2009. Available from: www.mooddisorderscanada.ca/documents/Media%20Room/Quick%20Facts%203rd%20Edition%20Referenced%20Plain%20Text.pdf. Accessed 2016 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistics Canada . Access to a regular medical doctor, 2013. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2014. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-625-x/2014001/article/14013-eng.htm. Accessed 2016 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wide J, Mok H, McKenna M, Ogrodniczuk JS. Effect of gender socialization on the presentation of depression among men. A pilot study. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e74–8. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/57/2/e74.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2016 May 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien R, Hunt K, Hart G. “It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate”: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(3):503–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.008. Epub 2005 Feb 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brownhill S, Wilhelm K, Barclay L, Schmied V. ‘Big build’: hidden depression in men. Aust N Z J Entry. 2005;39(10):921–31. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reading CL, Wien F. Health inequalities and social determinants of aboriginal peoples’ health. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2009. Available from: http://ahrnets.ca/files/2011/02/NCCAH-Loppie-Wien_Report.pdf. Accessed 2016 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gone JP. A community-based treatment for Native American historical trauma: prospects for evidence-based practice. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4):751–62. doi: 10.1037/a0015390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patterson M, Somers JM, McIntosh K, Shiell A, Frankish CJ. Housing and support for adults with severe addictions and/or mental illness in British Columbia, 2007. Vancouver, BC: Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addictions; 2007. Available from: www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2007/Housing_Support_for_MHA_Adults.pdf. Accessed 2016 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldram JB. Aboriginal healing in Canada: studies in therapeutic meaning and practice. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smye V, Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Josewski V. Harm reduction, methadone maintenance treatment and the root causes of health and social inequities: an intersectional lens in the Canadian context. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mussell WJ. Warrior-caregivers: understanding the challenges and healing of First Nations men. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palepu A, Marshall BD, Lai C, Wood E, Kerr T. Addiction treatment and stable housing among a cohort of injection drug users. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyatt AE. Healing through culture for incarcerated aboriginal people. First Peoples Child Fam Rev. 2013;8(2):40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson NJ, Cordier R. A narrative review of Men’s Sheds literature: reducing social isolation and promoting men’s health and well-being. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21(5):451–63. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12019. Epub 2013 Jan 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isaacs A, Maybery D. Improving mental health awareness among rural aboriginal men: perspectives from Gippsland. Australas Psychiatry. 2012;20(2):108–11. doi: 10.1177/1039856212437256. Epub 2012 Mar 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams M. Raising the profile of aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s health: an indigenous man’s perspective. Aust Aborig Stud. 2006;2:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulman J, Hayes R. Mibbinbah and spirit healing: fostering safe, friendly spaces for indigenous males in Australia. Int J Mens Health. 2011;10(1):6–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogrodniczuk J, Oliffe J, Kuhl D, Gross PA. Men’s mental health. Spaces and places that work for men. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:463–4. (Eng), e284–6 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.City of Vancouver . Downtown Eastside local area profile 2013. Vancouver, BC: City of Vancouver; 2013. Available from: http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/profile-dtes-local-area-2013.pdf. Accessed 2016 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucher JA. Using the logic model for planning and evaluation: examples for new users. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2010;22(5):325–33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(6):574–82. doi: 10.1080/13607860600641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackenzie CS, Pagura J, Sareen J. Correlates of help-seeking and perceived need for mental health services among older adults in the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(12):1103–15. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackenzie CS, Reynolds K, Cairney J, Streiner D, Sareen J. Disorder-specific mental health service use for mood and anxiety disorders: associations with age, sex, and psychiatric comorbidity. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(3):234–42. doi: 10.1002/da.20911. Epub 2011 Nov 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization . Health impact assessment (HIA): the determinants of health. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en. Accessed 2016 May 2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thoits PA. Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1):S41–53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohrer JE, Young R, Sicola V, Houston M. Overall self-rated health: a new quality indicator for primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(1):150–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macaulay A. Improving aboriginal health. How can health care professionals contribute? Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:334–6. (Eng), 337–9 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]