Abstract

Increasing evidence observed in clinical phenotypes show that abrupt breathing disorders during sleep may play an important role in the pathogenesis of sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS). The reported Brugada syndrome causing mutation R1512W in cardiac sodium channel α subunit encoded gene SCN5A, without obvious loss of function of cardiac sodium channel in previous in vitro study, was identified as the first genetic cause of Chinese SUNDS by us. The R1512W carrier was a 38-year-old male SUNDS victim who died suddenly after tachypnea in nocturnal sleep without any structural heart disease. To test our hypothesis that slight acidosis conditions may contribute to the significant loss of function of mutant cardiac sodium channels underlying SUNDS, the biophysical characterization of SCN5A mutation R1512W was performed under both extracellular and intracellular slight acidosis at pH 7.0. The cDNA of R1512W was created using site-directed mutagenesis methods in the pcDNA3 plasmid vector. The wild type (WT) or mutant cardiac sodium channel R1512W was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells. Macroscopic voltage-gated sodium current (INa) was measured 24 hours after transfection with the whole-cell patch clamp method at room temperature in the HEK293 cells. Under the baseline conditions at pH 7.4, R1512W (−175 ± 15 pA/pF) showed about 30% of reduction in peak INa compared to WT (−254 ± 23 pA/pF, P < 0.05). Under the acidosis condition at pH 7.0, R1512W (−130 ± 17 pA/pF) significantly decreased the peak INa by nearly 50% compared to WT (−243 ± 23 pA/pF, P < 0.005). Compared to baseline condition at pH 7.4, the acidosis at pH 7.0 did not affect the peak INa in WT (P > 0.05) but decreased peak INa in R1512W (P < 0.05). This initial functional study for SCN5A mutation in the Chinese SUNDS victim revealed that the acidosis aggravated the loss of function of mutant channel R1512W and suggested that nocturnal sleep disorders-associated slight acidosis may trigger the lethal arrhythmia underlying the sudden death of SUNDS cases in the setting of genetic defect.

Keywords: Brugada syndrome, forensic pathology, mechanism of death, sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome

1. Introduction

Sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), an entity with uncertain etiology, prevails predominantly in Southeast Asia and was named as Bangungut in the Philippines,[1] Lai Tai in Thailand,[2] Pokkuri in Japan,[3] and sudden manhood death syndrome in China.[4–6] SUNDS has unique clinical phenotype[1–5]: the vast majority of decedents were apparently healthy young males aged 20 to 40 years; death occurred during night sleep with typical symptoms of groaning, tachypnea, and abrupt tic of limbs; and comprehensive forensic autopsy examination revealed no morphological changes to explain the cause of death.

The clinical phenotype including ECG characteristics in SUNDS survivors indicated that SUNDS is similar to Brugada syndrome (BrS),[7] which is related to loss-of-function mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel α subunit.[8] Subsequently, with the identification of 3 SCN5A mutations in 3 of 10 probands with clinical evidence of SUNDS, SUNDS and BrS were thought most likely to be phenotypically, genetically, and functionally the same allelic disorder.[9] We initially performed molecular autopsy studies of SCN5A genes among a Chinese SUNDS cohort[4,10] and consequently confirmed the genetic association between BrS and SUNDS.

We formerly detected and determined the mutant R1512W in SCN5A to be the first genetic cause of Chinese SUNDS.[4,10] It was previously identified as a pathogenic SCN5A variant in 2 BrS patients from the Netherlands[11] and France,[12] respectively. However, the electrophysiological studies of this variant in hH1 (with Q1077 in SCN5A) background with heterologous expression systems did not show typical loss-of-function (decreased peak current) of sodium channels, and only manifested mild kinetics alterations (negative voltage shift of the steady-state activation and inactivation curves[11] or slow time constants of inactivation and recovery from inactivation[12]). Later, Ackerman et al[13] even found R1512W in 1 of 103 healthy Hispanics (unclear whether the variant carrier was truly healthy). All of these findings resulted in a conundrum and uncertainty in whether and how R1512W causes arrhythmia underlying BrS or SUNDS.

The abrupt breathing disorders in sleep (such as outbursts of tachypnea, strange groans or gasping, screams, and abnormal snores), observed to be the main clinical symptoms of SUNDS,[1–5] strongly suggest that sudden breathing abnormalities in nocturnal sleep may be a key trigger for SUNDS.[14,15] Sleep monitoring experiments revealed that nocturnal hypoxia might be the primary abnormality in SUNDS.[16] A population-based sleep investigation has indicated that the unique Hmong sleep disorders (a high prevalence of sleep apnea, sleep paralysis, and other rapid eye movement-related sleep abnormalities) may contribute to the high incidence of SUNDS in Hmong men in the United States.[17]

To address whether nocturnal breathing disorders associated with acidosis result in the significant loss-of-function of mutant cardiac sodium channel R1512W, which may account for sudden death of this SUNDS victim, we biophysically characterized this mutation under slight acidosis conditions in HEK293 cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples. All coding region exons and relevant exon–intron boundaries for corresponding candidate genes were PCR amplified. The PCR products were sequenced and analyzed as we previously described.[4,10,18–21] The principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. The project was approved for human research by the ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen University.

2.2. Plasmid constructions

R1512W was created in the SCN5A-Q1077del background (without Q1077, Genbank accession no. AY148488) using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as we previously reported.[22–26] The clone was sequenced to confirm the presence of the R1512W mutation and the absence of other substitutions that might occur during PCR.

2.3. Mammalian cell transfection

The pMaxGFP, with either the wild type (WT) or mutant channel R1512W in SCN5A, were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells with FuGENE6 reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) according to manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Electrophysiological measurements

Macroscopic voltage-gated sodium current (INa) was measured 24 hours after transfection with the whole-cell patch clamp method at room temperature (∼22°C) in the HEK293 cells under both normal pH and slight acidosis (extracellular and intracellular pH 7.0) conditions. The intracellular solution contained the following (in millimoles per liter): CsF 120, CsCl2 20, EGTA 2, NaCl 5, and HEPES 5, and was adjusted to pH 7.4 or 7.0 with CsOH. The extracellular solution contained the following (in millimoles per liter): NaCl 140, KCl 4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 0.75, and HEPES 5, and was adjusted to pH 7.4 or 7.0 with NaOH. Microelectrodes were manufactured from borosilicate glass using a puller (P-87, Sutter Instrument Co, Novato, CA). The resistances of microelectrodes ranged from 1.2 to 2.2 MΩ. Voltage clamp data were generated with pClampex 10.5 and analyzed using Clampfit 10.5 (Molecular devices corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). Membrane current data were digitalized at 100 kHz, low-pass filtered at 5 kHz, and then normalized to membrane capacitance. Standard voltage clamp protocols were used and data were measured and analyzed as described previously.[22–26]

The curves of activation were fit with a Boltzmann function: GNa = (1 + exp [V1/2−V]/K)−1, wherein V1/2 and K are the midpoint and slope factor, respectively. G/GNa = INa (norm)/(V−Vrev), wherein Vrev is the reversal potential and V is the membrane potential. Steady-state availability from inactivation was determined by fitting the data to the Boltzmann function: INa = INa-max (1 + exp [Vc−V1/2]/K)−1, wherein V1/2 and k are the midpoint and the slope factor, respectively, and Vc is the membrane potential. Late INa was measured as the mean current between 600 and 700 ms after the initiation of the depolarization from−140 to −20 mV for 750 ms.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All data points are reported as the mean value and the standard error of the mean (SEM). Determinations of statistical significance were performed using a Student t test for comparisons of 2 means or using analysis of one-way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni test for comparisons of multiple groups. Statistical significance was determined by a value of P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Case report of the SUNDS victim

A 38-year-old male without cardiac disease history was witnessed by his roommate to have sudden tachypnea and abrupt tic of limbs during sleep at 4 am in the morning. His roommate transported him immediately to a local hospital where he was identified and declared dead. The comprehensive gross and microscopic autopsies revealed no obvious pathological changes to explain the sudden unexpected death of this apparently healthy worker.[4] He did not have a family history of sudden cardiac death and was diagnosed as SUNDS.

3.2. Mutational analysis

Comprehensive open-reading frame/splice site mutational analysis for the SCN5A gene revealed a missense heterozygous variant (4534 C>T, R1512W). R1512W was absent in 230 reference alleles in the control group.[4] The subsequent mutational analysis for arrhythmia-associated genes (SCN1B-4B, MOG1, GPD1-L, RyR2, PKP2, KCNQ1, KCNH2, KCNE1, KCNE2, and DSP) did not show pathogenic rare variants in this case.[10,18–21] The follow-up genetic investigation for the parents of this case did not yield SCN5A-R1512W mutation.

3.3. Electrophysiology

Compared with Q1077 (hH1), the Q1077del cDNA reflects the most abundant alternatively spliced SCN5A transcript (∼65%) in human hearts.[22] We tested R1512W in the SCN5A-Q1077del background in HEK293 cells as in our previous functional studies of SCN5A.[22–26]

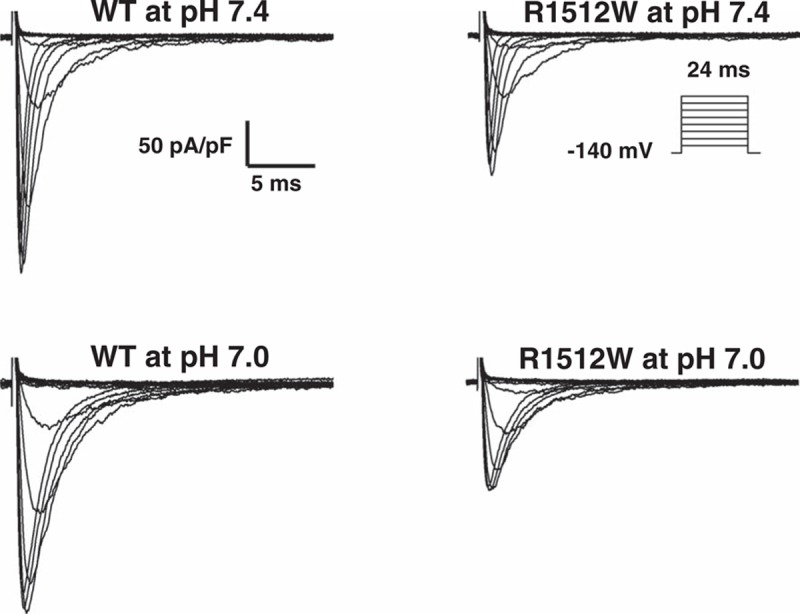

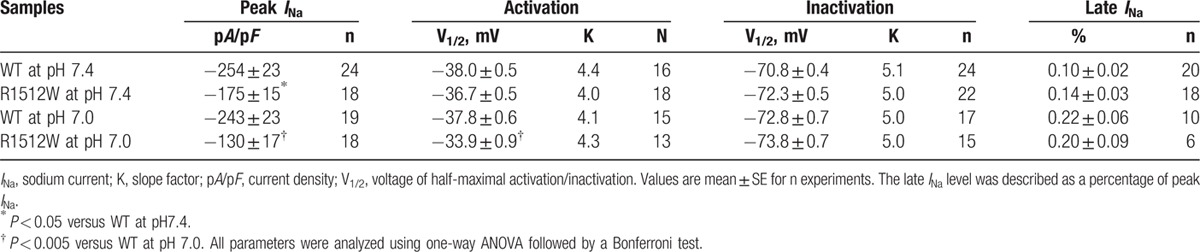

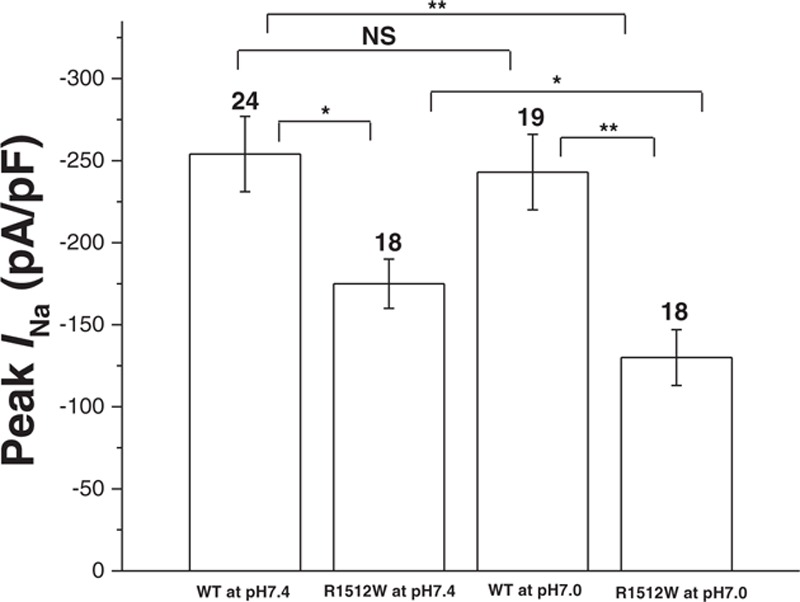

We recorded the biophysical characteristics under both baseline pH (7.4) and acidosis conditions (pH 7.0). Under baseline pH, compared to WT sodium channels (−254 ± 23 pA/pF), R1512W channels (−175 ± 15 pA/pF, P < 0.05) showed around 30% of reduction in peak INa (Fig. 1, Table 1). There were no obvious differences between WT and R1512W in late INa (Table 1). Under the acidosis conditions at pH 7.0 and compared with WT (−243 ± 23 pA/pF), R1512W (−130 ± 17 pA/pF, P < 0.005) showed significantly decreased peak INa of approximately 50% (Fig. 1, Table 1). Again, the late INa showed no significant differences between WT and R1512W (Table 1). The summary data for peak INa density (Table 1 and Fig. 2) showed that the acidosis at pH 7.0 did not affect the peak INa in WT (P > 0.05), but decreased the peak INa in R1512W (P < 0.05), compared to baseline conditions at pH 7.4.

Figure 1.

Representative whole-cell current traces in HEK 293 cells. Representative whole-cell current traces showing peak sodium current under both baseline (pH 7.4) and acidosis (pH 7.0) conditions in HEK293 cells expressing wild-type or mutant R1512W- SCN5A.

Table 1.

Biophysical properties of WT or variant sodium channel R1512W in HEK293 cells.

Figure 2.

Summary data for peak sodium current in HEK293 cells. Summary data of peak sodium current densities from each group. The number of tested cells is indicated above the bar. NS, no significant difference. ∗P < 0.05. ∗∗P < 0.005 (one-way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni test).

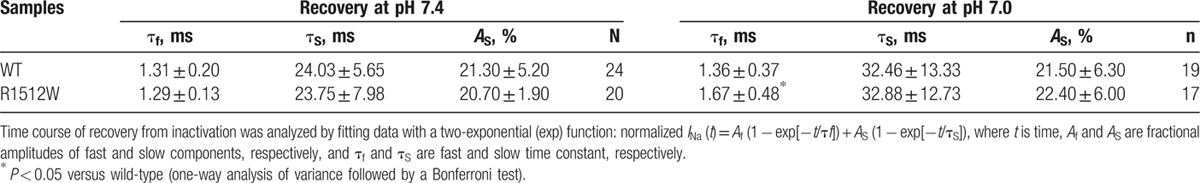

We analyzed the kinetic parameters of activation and inactivation at both baseline pH and pH 7.0 for WT and R1512W. There were no significant differences between any 2 groups in both activation and inactivation (Table 1). For recovery from inactivation, R1512W at pH 7.0 exhibited slower recovery from inactivation and had significantly larger fast time constants (τf) values compared with any other group (Table 2), suggesting that acidosis conditions interrupted the recovery from inactivation of R1512W channels. No significant difference of the fractional amplitudes of fast (Af) and slow (AS) components was observed between any 2 groups (Table 2, Af values not shown).

Table 2.

Recovery of WT or variant sodium channel R1512W in HEK293 cells.

4. Discussion

Although the SCN5A mutation R1512W was genetically linked with 2 separate BrS patients and 1 SUNDS victim, the reported absence of significant loss-of-function of this mutant sodium channel and the existence of this mutation in a “healthy” individual make it uncertain whether or not the mutation is truly pathogenic.

In this investigation, we provide the first evidences that R1512W resulted in statistically significant loss-of-function of sodium channels by decreasing peak INa by 30%. These biophysical findings definitely show that R1512W by itself exerts mild but actual effects on sodium channel function in the most abundant Q1077del-SCN5A background. There exists mRNA for 2 splice variants of SCN5A (containing or lacking a glutamine at position 1077) in the human heart at a ratio of about 1:2 (Q1077:Q1077del).[22] We previously identified that the function of INa for arrhythmia- and cardiomyopathy-associated variants[23–26] depends largely on the Q1077 or Q1077del splice variant background. Our data again suggest the utmost importance of characterizing putative arrhythmia variants in both backgrounds to determine their possible pathogenicity. Moreover, the significant dependence of electrophysiological characteristics on the Q1077/Q1077del backgrounds indicates possible splice variants-based regulatory mechanisms by which cardiac sodium channels maintain normal function.[25,26]

Plant et al,[27] Wang et al,[28] and we[25] have previously investigated the effects of intracellular acidosis on the late INa at pH 6.7 for SCN5A variants S1103Y, R680H, and S1103Y/R680H, respectively, and identified acidosis as an important etiologic factor by significantly increasing late INa. Considering that the SUNDS victim carrying R1512W might have involved slight acidosis because of his sleep breathing disorder before sudden death,[4] we characterized the biophysical phenotype of R1512W under both intracellular and extracellular acidosis at pH 7.0. Notably, the acidosis significantly aggravated the loss-of-function of R1512W channels (∼50% reduction in peak INa compared to WT at normal pH), whereas the WT channels remained intact under these conditions. These findings confirm the key role of environmental risk factors (such as acidosis, medications, hypokalemia, etc) in the occurrence of arrhythmia. The hypothesis that SUNDS may be a sleep and/or respiratory disorder-associated arrhythmia syndrome was conceived[4,14,15] and investigated[16,17] for decades in epidemiological studies. The significant different biophysical phenotype of R1512W between baseline and slight acidosis conditions strongly support the idea that nocturnal sleep breathing abnormalities-related acidosis may be a trigger for fatal arrhythmias in patients with pathogenic mutations in arrhythmia susceptibility genes.

The SCN5A gene is so far the most common BrS-susceptibility gene responsible for 20% to 30% of the disorder. Vatta et al[9] proposed SUNDS and BrS as the same allelic disorder based on genetic and functional studies of SCN5A mutations found in 3 of 10 SUNDS cases. In a much larger cohort of 123 SUNDS cases, we identified 10 putative pathogenic SCN5A variants and some arrhythmia-susceptible polymorphisms.[10] These studies implicated the important role of SCN5A in the pathogenesis of both BrS and SUNDS. However, according to regular biophysical study and/or the strict American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guideline definition,[29] many SCN5A rare variants or polymorphisms are not considered to be “pathogenic” or likely “pathogenic.” If environmental risk factors (such as acidosis) are involved in assessing the pathogenicity of SCN5A variants in specific individuals, there will probably be more SCN5A variants that would account for BrS and SUNDS.

The abnormal biophysical phenotype of R1512W identified in this study is a complimentary finding for previous studies, which confirmed R1512W as a BrS-causing variant. However, there were no distinct significant kinetic changes to explain the electrophysiological modifications of this variant. The mechanisms by which acidosis remarkably decreased peak INa may be related to slower recovery from inactivation. The limitations of this functional investigation include the in vitro nature of the study using “forced” expression of mutant sodium channel in noncardiac myocytes and the absence of genetic background for each specific patient. Thus, the detailed biophysical mechanisms for R1512W to cause BrS or SUNDS remain to be determined in mammalian cardiomyocytes and patient-specific inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes.

Under the condition of 60-minute no-flow ischemia, extracellular and intracellular pH in cardiac tissue have been reported to decrease below pH 6.0.[30] Sudden infant death syndrome is associated with sleep respiratory disorders wherein the arterial blood pH is found to be less than pH 7.0.[31] Although the clinical phenotype of breathing disorders (such as sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxia) is presumed to be a critical trigger for SUNDS[14–16] and the biophysical phenotype in vitro study suggests low pH can significantly change the function of mutant cardiac sodium channel underlying BrS,[31] the mechanism of how pH in vivo changes and how it affects life-threatening arrhythmia needs further investigation in both SUNDS and BrS patients.

In summary, we characterized in this study the first SCN5A variant in Chinese SUNDS victims. We revealed that this R1512W variant caused statistically decreased peak INa and that acidosis aggravated the loss of function of this mutant channel in the most common SCN5A background (Q1077del). Our data provide the biophysical evidence for the hypothesis that sleep breathing disorder-associated acidosis may be a trigger for the lethal arrhythmia underlying sudden cardiac death of SUNDS cases in the setting of genetic defect.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACMG = American College of Medical Genetics, BrS = Brugada syndrome, INa = voltage-gated sodium current, SUNDS = sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome, WT = wild type.

JZ, FZ, TS, and LH contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the Key Program (81430046) and General Program (81172901) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Cheng), and the grants R56 HL71092 & R01HL128076–01 from the National Institutes of Health of the United States of America (Makielski).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Aponte GE. The enigma of bangungut. Ann Intern Med 1960; 52:1258–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tungsanga K, Sriboonlue P. Sudden unexplained death syndrome in north-east Thailand. Int J Epidemiol 1993; 22:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katsuyuki Nakajima, Sanae Takeichi, Yasuhiro Nakajima, et al. Pokkuri death syndrome: sudden cardiac death cases without coronary atherosclerosis in South Asian young males. Forensic Sci Int 2011; 207:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng J, Makielski JC, Yuan P, et al. Sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in Southern China: an epidemiological survey and SCN5A gene screening. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2011; 32:359–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng J, Huang E, Tang S, et al. A case-control study of sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in the southern Chinese Han population. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2015; 36:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Q, Zhang L, Zheng J, et al. Forensic Pathological Study of 1656 Cases of Sudden Cardiac Death in Southern China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95 5:e2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sangwatanaroj S, Prechawat S, Sunsaneewitayakul B, et al. New electrocardiographic leads and the procainamide test for the detection of the Brugada sign in sudden unexplained death syndrome survivors and their relatives. Eur Heart J 2001; 22:2290–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizusawa Y, Wilde AA. Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012; 5:606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vatta M, Dumaine R, Varghese G, et al. Genetic and biophysical basis of sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), a disease allelic to Brugada syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 2002; 11:337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Tester DJ, Hou Y, et al. Is sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in Southern China a cardiac sodium channel dysfunction disorder? Forensic Sci Int 2014; 236:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rook MB, Bezzina Alshinawi C, Groenewegen WA, et al. Human SCN5A gene mutations alter cardiac sodium channel kinetics and are associated with the Brugada syndrome. Cardiovasc Res 1999; 44:507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deschênes I, Baroudi G, Berthet M, et al. Electrophysiological characterization of SCN5A mutations causing long QT (E1784K) and Brugada (R1512W and R1432G) syndromes. Cardiovasc Res 2000; 46:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackerman MJ, Splawski I, Makielski JC, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of cardiac sodium channel variants among black, white, Asian, and Hispanic individuals: implications for arrhythmogenic susceptibility and Brugada/long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm 2004; 1:600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vertes RP. A life-sustaining function for REM sleep: a theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1986; 10:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanchaiswad W. Is sudden unexplained nocturnal death a breathing disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 49:111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charoenpan P, Muntarbhorn K, Boongird P, et al. Nocturnal physiological and biochemical changes in sudden unexplained death syndrome: a preliminary report of a case control study. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1994; 25:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young E, Xiong S, Finn L, et al. Unique sleep disorders profile of a population-based sample of 747 Hmong immigrants in Wisconsin. SocSci Med 2013; 79:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, Zhao Q, Su T, et al. Postmortem molecular analysis of KCNQ1, KCNH2, KCNE1 and KCNE2 genes in sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in the Chinese Han population. Forensic Sci Int 2013; 231:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang L, Liu C, Tang S, et al. Postmortem genetic screening of SNPs in RyR2 gene in sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in the southern Chinese Han population. Forensic Sci Int 2014; 235:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Q, Chen Y, Peng L, et al. Identification of rare variants of DSP gene in sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome in the southern Chinese Han population. Int J Legal Med 2016; 130:317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L, Tang S, Peng L, et al. Molecular autopsy of desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 in sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome. J Forensic Sci 2016; 61:687–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makielski JC, Ye B, Valdivia CR, et al. A ubiquitous splice variant and a common polymorphism affect heterologous expression of recombinant human SCN5A heart sodium channels. Circ Res 2003; 93:821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan BH, Valdivia CR, Rok BA, et al. Common human SCN5A polymorphism have alterd electrophysiology when expressed in Q1077 splice variants. Heart Rhythm 2005; 2:741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan BH, Valdivia CR, Song C, et al. Partial expression defect for the SCN5A missense mutation G1406R depends on splice variant background Q1077 and rescue by mexiletine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006; 291:H1822–H1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng J, Tester DJ, Tan BH, et al. The common African American polymorphism SCN5A-S1103Y interacts with mutation SCN5A-R680H to increase late Na current. Physiol Genomics 2011; 43:461–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng J, Morales A, Siegfried JD, et al. SCN5A rare variants in familial dilated cardiomyopathy decrease peak sodium current depending on the common polymorphism H558R and common splice variant Q1077del. Clin Transl Sci 2010; 3:287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plant LD, Bowers PN, Liu Q, et al. A common cardiac sodium channel variant associated with sudden infant death in African Americans, SCN5A S1103Y. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:430–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang DW, Desai RR, Crotti L, et al. Cardiac sodium channel dysfunction in sudden infant death syndrome. Circulation 2007; 115:368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015; 17:405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.EI Banani H, Bernard M, Baetz D, et al. Changes in intracellular sodium and pH during ischaemia-reperfusion are attenuated by trimetazidine. Comparison between low- and zero-flow ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res 2000; 47:688–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters CH, Abdelsayed M, Ruben PC. Triggers for arrhythmogenesis in the Brugada and long QT 3 syndromes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2016; 120:77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]