Abstract

As recommended by most recent antiemetic guidelines, the optimal prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) requires the combination of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (RA) with an NK1-RA. Moreover, the major predictors of acute and delayed CINV include: young age, female sex, platinum- or anthracycline-based chemotherapy, nondrinker status, emesis in the earlier cycles of chemotherapy, and previous history of motion/morning sickness. Despite improved knowledge of the pathophysiology of CINV and advances in the availability of active antiemetics, an inconsistent compliance with their use has been reported, thereby resulting in suboptimal control of CINV in several cases. In this scenario, a new anti-emetic drug is now available, which seems to be able to guarantee better prophylaxis of CINV and improvement of adherence to guidelines. In fact, netupitant/palonosetron (NEPA) is a ready-to-use single oral capsule, combining an NK1-RA (netupitant) and a 5-HT3-RA (palonosetron), which is to be taken 1 hour before the administration of chemotherapy, ensuring the coverage from CINV for 5 days. We reviewed the role of NEPA in patients at high risk of CINV receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. In these patients, NEPA plus dexamethasone, as compared to standard treatments, achieved superior efficacy in all primary and secondary end points during the acute, delayed, and overall phases, including nausea assessment. Moreover, these results were also achieved in female patients receiving anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy. NEPA represents a real step forward in the prophylaxis of CINV.

Keywords: NEPA, netupitant, NK1, CINV, vomiting, risk factors

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is the most unpleasant side effect of treatment, and, in particular, nausea is still cited by patients as the one with the highest impact on their quality of life.1

Patients undergoing chemotherapy show three different types of emesis (acute, delayed, and overall), each having particular characteristics.1 In fact, acute emesis, which develops within 24 hours after the administration of chemotherapy, and delayed emesis, which develops 24 hours after chemotherapy and can persist for a number of days, are controlled by different pathways and need different pharmacological approaches.2,3

Modern prophylaxis of CINV includes the administration of a drug that inhibits serotonin (5-HT3 receptor antagonist [RA]), the major neurotransmitter responsible for acute nausea and vomiting in association with a drug that inhibits P-substance (NK1-RA), and the major neurotransmitter responsible for delayed nausea and vomiting.

The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/European Society for Medical Oncology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network4–6 recommend, for all patients with cancer receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) and for those at particular high risk receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC), the concomitant administration of an NK1-RA and a 5-HT3-RA in association with dexamethasone.

Prophylaxis of CINV and antiemetic drugs: 5-HT3-RA and NK1-RA

Two classes of antiemetics have helped to improve the control of CINV: 5-HT3-RA in combination with dexamethasone and NK1-RA. Both classes of drugs are available in oral and intravenous formulations and are usually administered together. In addition, a fixed combination in a single capsule has been recently developed (netupitant/palonosetron [NEPA]).7

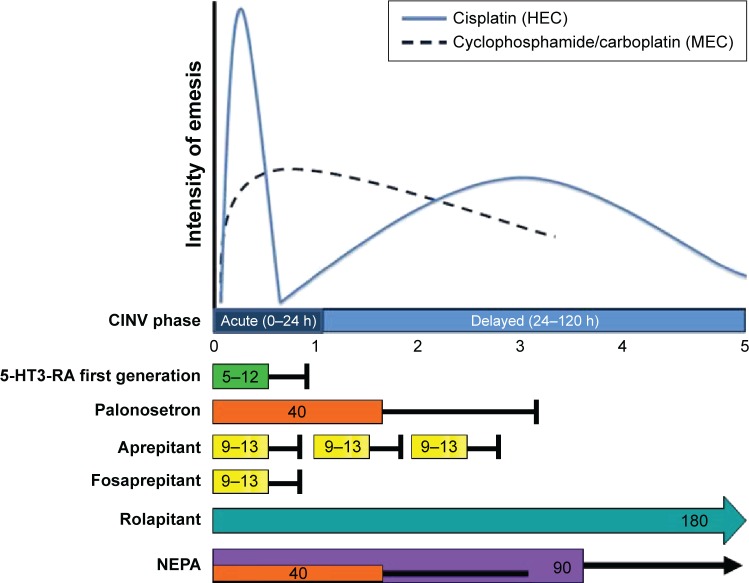

Figure 1 summarizes the half-life of different antiemetic drugs that are available (both 5-HT3-RA and NK1-RA) related to the intensity of emesis for HEC and MEC.8,9

Figure 1.

Intensity of emesis according to HEC and MEC.

Notes: Half-life (hours) of approved 5-HT3-RA and NK1-RA is reported. Half-life of first generation of 5-HT3-RA ranges from 5 hours to 6 hours for ondansetron and from 5 hours to 12 hours for granisetron.

Abbreviations: CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; HEC, highly emetogenic chemotherapy; 5-HT3-RA, 5-HT3 receptor antagonist; MEC, moderately emetogenic chemotherapy; NEPA, netupitant/palonosetron; NK1-RA, NK1 receptor antagonist; h, hours.

The aim of this review is to define the role of NEPA in the management of the prophylaxis of CINV by risk profile in patients with cancer.

5-HT3-RA

Serotonin RAs are essential drugs for the prophylaxis of CINV, having a major role in the prevention of the acute phase.10 5-HT3-RAs are classified into two well-defined classes characterized by pharmacological, pharmacodynamic, and clinical features:

First-generation 5-HT3-RA: ondansetron, dolasetron, granisetron, tropisetron.

Second-generation 5-HT3-RA: palonosetron.

Palonosetron (Aloxi©) is a 5-HT3-RA that, compared to the first-generation setrons, has a prolonged plasma half-life (40 hours vs 3–9 hours), a strong binding affinity to the receptor (100 times higher), and a specific interaction with it (allosteric cooperative and positive binding vs a simply competitive binding).11 As compared to old “setrons”, the pharmacological and pharmacodynamic features of palonosetron translate into a statistically significant clinical superiority, in the control of CINV for the whole duration of the period at risk (1–5 days), with a single administration on the day of the administration of chemotherapy.12–14

On the other hand, the first-generation 5-HT3-RAs require the administration of one or more doses to control acute emesis on day 1, and repeated administrations for the control of delayed emesis (on the following 2–6 days). The clinical superiority of palonosetron is also associated with an improved safety profile; in particular, unlike other setrons, the prolongation of the corrected QT (name for the measure of time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave on an electrocardiogram) (QTc) interval has never been reported.15–19

NK1-RAs

The introduction of NK1-RA has enhanced the efficacy of antiemetic prophylaxis above all to control vomiting in both the acute and the delayed phases. P-substance RAs are drugs recommended for the prophylaxis of delayed phase of CINV, which are always in association with 5-HT3-RAs, and they were approved for the prevention of CINV in both HEC and MEC.20,21 Safety profile of NK1-RA is well defined; the most frequent adverse events are fatigue and decrease in appetite.20,21

Aprepitant (Emend®) was the first approved P-substance RA in the NK1-RA class.20 Aprepitant requires three oral administrations: on day 1 before chemotherapy (outpatient regimen) and on days 2 and 3 (at home).20 Aprepitant has been shown to have a moderate inhibitory effect as well as a possible inductive effect on cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4. Due to this interaction, dexamethasone dosage should be decreased in combination with aprepitant: 12 mg instead of 20 mg.20

The intravenous formulation of aprepitant, fosaprepitant (FOS; Ivemend©), is administered in a single dose on day 1, but it requires the administration of multiple doses of dexamethasone on days 2–4.20 Safety profile of both oral and intravenous formulation is similar, except for the risk of infusion site reaction for FOS.22 FOS in combination with anthracycline-based chemotherapy (anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide [AC], FEC, R/CHOP) is associated with a frequent (>30%) and severe incidence of injection site reaction (deep vein thrombosis, phlebitis).23,24

No QTc prolongation, heart rate, or cardiac events have been detected with aprepitant or FOS use.

Rolapitant (ROL; Varubi©) is a highly selective long-acting NK1-RA (half-life 180 hours), and it is orally active. ROL is administered on day 1 only (two capsules of 90 mg each), before the administration of chemotherapy. However, multiple doses of dexamethasone on days 3–4 for HEC and multiple doses of oral 5-HT3-RA on days 2–3 for MEC are administered in the delayed phase.25 Both HEC and MEC pivotal studies have evaluated ROL in association with other antiemetic therapies during the delayed phase of CINV, and in the future studies it could be interesting to evaluate whether the long-acting ROL could spare the use of other antiemetic drugs in the days following chemotherapy.25,26 ROL is metabolized by CYP3A4, but it does not induce or inhibit it avoiding reduction in dexamethasone; however, it may have interaction with drugs metabolized by cytochrome CYP2D6. Due to this interaction, ROL is contraindicated in combination with thioridazine, since the combination may result in QT prolongation and torsade de pointes (a specific form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia occurring in the context of QT prolongation).26 In addition, the concomitant use of ROL and pimozide requires QT prolongation monitoring.26

NEPA

The fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron (Akynzeo©), also known as NEPA, is an association of netupitant (300 mg), a new NK1-RA, and palonosetron (0.50 mg).9 The two active principles act on the different pathways associated with CINV pathogenesis and are administered as a single capsule 1 hour before the chemotherapy cycle.27

Netupitant, the NK1-RA component of NEPA, is a new highly selective antagonist of the P-substance receptor that can saturate NK1 receptors up to 90% and has a long half-life (96 hours) as compared to aprepitant (9–13 hours).9

Palonosetron, the 5-HT3-RA component of NEPA, is able to inhibit cross-talk between 5-HT3 and NK1 receptors, thus inhibiting NK1-mediated response to P-substance stimulation.

The rationale for the combination of the two active principles of NEPA is based on their complementary action on NK1 receptor. The synergic effect on the inhibition of NK1-RA and the similar pharmacokinetics characteristics (long half-life) of NEPA emerged in in vitro studies and have been confirmed in clinical studies.28,29

NEPA, with respect to other single-day NK1-RAs such as FOS (single infusion) or ROL (two capsules on day 1), is a single capsule, is ready to use, and does not require multiple doses of dexamethasone or 5-HT3-RA on days 2–4. In particular, patients receiving HEC treated with FOS or ROL should receive five (FOS) or six (ROL) doses of dexamethasone in the delayed phase instead of the three doses required for NEPA. In particular, in the case of MEC, ROL requires four doses of 5-HT3-RA during the delayed phase, with respect to none required for FOS or NEPA.30

Recently, the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines published an expedited update to introduce the key recommendation of NEPA as antiemetic option for patients receiving HEC.31

CINV risk factors

Prognostic factors for CINV have been identified during the past decades.32 Recently, Warr published an exhaustive review on CINV prognostic factors highlighting those with well-established evidence as: type of chemotherapy, young age, female sex, previous nausea or vomiting for different causes (previous chemotherapy, pregnancy, or motion sickness), and alcohol consumption of <1.5 oz/d, and those with a limited or contradictory evidence as: anxiety, expectation, and concomitant use of opioid.33

Actually, antiemetic guidelines recommend the antiemetic prophylaxis regimen according to the type of chemotherapy, except for the combination of anthracycline and doxorubicin AC in patients with breast cancer.31 In fact, patients with breast cancer receiving AC-based chemotherapy are at particular risk of CINV due to the synergistic emetic effect of chemotherapy and patient risk factors, such as young female and no alcohol user.

The assessment of emetogenic potential and individual patient risk factors is essential to creating an emetogenic care plan that meets patient needs. Antiemetic therapy combined with individualized patient education, clear communication, and the management of expectations, positions patients to achieve optimal emetogenic control.34

Type of chemotherapy

Antiemetic prophylaxis guidelines for HEC and AC-based chemotherapy recommend the use of a triple combination of NK1-RA, a 5-HT3-RA, and dexamethasone.

Because of the use of different drugs on days following chemotherapy, patients with cancer need to take antiemetic drugs at home, increasing the risk of lack of compliance.26,35,36

In fact, an European study evaluating >1,000 patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy and antiemetic prophylaxis demonstrated that adherence to the prophylaxis of emesis, as recommended in guidelines, was very low in these patients and that low adherence was associated with the lack of control of CINV (P=0.008).37

The simplified antiemetic prophylaxis with NEPA, now available, gives the clinicians a therapeutic option ensuring optimal adherence to therapy, a key requirement to obtain the maximum efficacy in the prophylaxis of CINV.32

The single oral administration of a capsule of NEPA is the prerequirement for the maximum adherence to the prophylaxis of CINV in both acute and delayed phases, especially because this administration occurs 1 hour before chemotherapy under medical supervision.32

Efficacy of NEPA in preventing CINV induced by HEC has been evaluated in a formal pivotal study comparing the drug with palonosetron, which is known to be superior to all the first-generation 5-HT3-RAs. In this study, NEPA was statistically superior to palonosetron in preventing emesis and nausea, and in the use of rescue medication during acute, delayed, and overall phases as well.30 Tables 1 and 2 summarize the main results achieved by NEPA.38,39

Table 1.

Efficacy of NEPA vs PALO (control) during the first cycle of cisplatin-based HEC (pivotal study NETU-07-07)

| NETU-07-07; HEC | Complete responsea

|

No vomiting

|

No significant nauseab

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEPA (300 mg)

|

PALO (0.5 mg)

|

NEPA (300 mg)

|

PALO (0.5 mg)

|

NEPA (300 mg)

|

PALO (0.5 mg)

|

|

| N=135 | N=136 | N=135 | N=136 | N=135 | N=136 | |

| Acute (0–24 hours) vs control | 98.5% | 89.7% | 98.5% | 89.7% | 98.5% | 93.4% |

| P=0.007 | P=0.007 | P=0.050 | ||||

| Delayed (24–120 hours) vs control | 90.4% | 80.1% | 91.9% | 80.1% | 90.4% | 80.9% |

| P=0.018 | P=0.006 | P=0.004 | ||||

| Overall (0–120 hours) vs control | 89.6% | 76.5% | 91.1% | 76.5% | 89.6% | 79.4% |

| P=0.004 | P=0.001 | P=0.021 | ||||

Notes:

No vomiting and no use of rescue medication.

Visual analog scale score of <25 mm. Reproduced from EMA [webpage on the Internet]. Summary of Product Characteristics of NEPA®. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003728/WC500188432.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2016.30

Abbreviations: NEPA, netupitant/palonosetron; HEC, highly emetogenic chemotherapy; N, number of patients; PALO, palonosetron; NETU, Netupitant.

Table 2.

Efficacy of NEPA vs PALO (control) during the first cycle of anthracycline–cyclophosphamide-based MEC (pivotal study NETU-08-18)

| NETU-08-18; MEC | Complete responsea

|

No vomiting

|

No significant nauseab

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEPA (300 mg)

|

PALO (0.5 mg)

|

NEPA (300 mg)

|

PALO (0.5 mg)

|

NEPA (300 mg)

|

PALO (0.5 mg)

|

|

| N=724 | N=725 | N=724 | N=725 | N=724 | N=725 | |

| Acute (0–24 hours) vs control | 88.4% | 85.0% | 90.9% | 87.3% | 87.3% | 87.9% |

| P=0.047 | P=0.025 | P=ns | ||||

| Delayed (24–120 hours) vs control | 76.9% | 69.5% | 81.8% | 75.6% | 76.9% | 71.3% |

| P=0.001 | P=0.004 | P=0.014 | ||||

| Overall (0–120 hours) vs control | 74.3% | 66.6% | 79.8% | 72.1% | 74.6% | 69.1% |

| P=0.001 | P≤0.001 | P=0.020 | ||||

Notes:

No vomiting and no use of rescue medication.

Visual analog scale score of <25 mm. Reproduced from EMA [webpage on the Internet]. Summary of Product Characteristics of NEPA®. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003728/WC500188432.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2016.30

Abbreviations: MEC, moderately emetogenic chemotherapy; N, number of patients; NEPA, netupitant/palonosetron; ns, not significant; PALO, palonosetron; NETU, Netupitant.

Sex

Female sex is a well-known patient risk factor for CINV.34 NEPA in female patients with cancer receiving AC-based chemotherapy was statistically superior in complete response (no vomiting and no use of rescue medication) during the acute, delayed, and overall phases, as compared to palonosetron.

Moreover, NEPA results were also superior to those achieved by aprepitant plus ondansetron, above all in the control of delayed CINV.39,40 Although these data do not come from a randomized study (we are still lacking data from a head-to-head comparison between NEPA and any other NK1-RAs in the setting of AC), it is important to note that in pivotal studies, aprepitant in association with ondansetron was not statistically superior to the 5-HT3-RA in the prophylaxis of delayed CINV in the same setting.40

Based on the clinical evidence from pivotal studies, the European Medicine Agency has deemed it appropriate to clearly state the efficacy in the prophylaxis of CINV in both the acute and delayed phases in the therapeutic indications of NEPA.30–36

In patients with breast cancer, the role of NEPA could be important also because of its cardiac safety profile, since those patients are at high risk to develop cardiomyopathy related to breast cancer treatment (chemotherapy, target therapy, and radiotherapy). The cardiotoxic effect of NEPA was studied in a randomized, placebo-controlled study vs active comparator (moxifloxacin), as requested by the regulatory authorities, the US Food and Drug Administration/European Medicine Agency, based on The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use E14 guidelines.41 The study included 197 healthy volunteers randomly assigned to four treatment groups (placebo, 200 mg netupitant + 0.5 mg palonosetron [NEPA200/0.5], 600 mg netupitant + 1.5 mg palonosetron [NEPA600/1.5, ie, an over-therapeutic dose], and 400 mg of moxifloxacin).42

This study showed no significant effects of NEPA on QTc prolongation, heart rate, PR interval, QRS, and cardiac morphology as compared to placebo, even with higher than therapeutic doses.42

Previous nausea or vomiting

Patients may have experienced previous vomiting episodes due to different causes: previous chemotherapy, pregnancy, or motion sickness.33 In these cases, it could be helpful for physicians to review with patients those risk factors before starting chemotherapy. Assessing this risk, the physician could implement a more aggressive antiemetic prophylaxis due to a specific predisposition of the patient to nausea and vomiting.33,34

A general rule to obtain the best prevention of CINV is to implement the recommended antiemetic prophylaxis from the first chemotherapy cycle.4–6

The role of NEPA in this setting could help physicians to guarantee the highest patient compliance when an NK1-RA in combination with 5-HT3-RA is recommended, since the long half-life of the two components, netupitant and palonosetron, allows controlling acute and delayed CINV with a single oral administration on the first day of chemotherapy cycle.43

This results into a simplified dosage schedule as compared to the multiple administrations required by unfixed associations of 5-HT3-RA and NK1-RA agents currently available.43

Age and alcohol user

Younger patients are at increased risk of CINV and above all in the pediatric setting.33

NEPA is not indicated in pediatric patients and a specific role in this setting could not be evaluated.30 For young patients, not pediatric, as also for nondrinker patients, the role of NEPA could be related to the simplicity of its administration in a unique dose.28

Conclusion

The physiopathology of CINV is multifactorial, with a serotonin-mediated acute phase and a P-substance-mediated delayed phase. Consequently, the prophylaxis of CINV requires a multimodal therapeutic approach: a 5-HT3-RA drug for the control of the acute phase associated with an NK1-RA drug for the control of the delayed phase.1–3

The most influential national and international guidelines recommend the use of a triple combination of 5-HT3-RA, NK1-RA, and dexamethasone for the prophylaxis of CINV based on the emetogenicity of chemotherapy: patients receiving HEC or high-risk MEC.4–6

Major predictor factors of acute and delayed CINV were consistent with the published literature and included: young age, female sex, platinum or anthracycline-based chemotherapy, nondrinker status, emesis in the earlier cycles of chemotherapy, and previous history of motion/morning sickness.33 Patient risk factors can increase the emetogenic risk of chemotherapy agents as occurring in patients with breast cancer receiving AC-based chemotherapy.34 Guidelines categorize doxorubicin as an agent of moderate risk; however, the female sex, young age, and nondrinker status reclassified this chemotherapy regimen as high risk, in which a triple combination is recommended.4–6,34 Patient risk factors for CINV are changing the approach of antiemetic guideline recommendations and, probably, in the future, the assessment risk for CINV will be managed with an algorithm, in the same way in which currently we assess the risk of febrile neutropenia.34

In this changing scenario, another issue that physicians should manage is the adherence to antiemetic guideline recommendations. Despite improved knowledge of the pathophysiology of CINV and advances in the range of antiemetics, there was inconsistent compliance with their use.

It is well known that in Europe, adherence to the prophylaxis of emesis, as recommended in the guidelines, is very low, and this significantly correlates with the lack of the control of CINV (P=0.008).37

In this article, we reviewed the most relevant CINV risk factors and we defined the possible role of the new antiemetic drug, NEPA, which is a single oral dose, combining an NK1-RA and 5-HT3-RA, to be taken 1 hour before chemotherapy. NEPA ensures the coverage of the 5 days posttreatment, without any additional 5-HT3-RA or NK1-RA drug to be taken by patients at home for antiemetic prophylaxis.32–34

NEPA has consistently proven statistically more effective than palonosetron alone in obtaining complete response in patients treated with HEC or MEC.

The role of NEPA related to CINV risk factor could be summarized as follows:

Chemotherapy risk factor: In patients undergoing HEC, the single oral dose of NEPA achieved superior efficacy for all primary and secondary end points during the acute, delayed, and overall phases, including nausea assessment.

In patients with breast cancer receiving AC-based chemotherapy, a single dose of NEPA + dexamethasone achieved optimal control of CINV for 5 days after the administration of chemotherapy. No antiemetic therapy should be prescribed for these patients. Moreover, the cardiac safety of NEPA (no QT prolongation) is of particular relevance in this setting.

Overall, the advantage of using NEPA in the prophylaxis of CINV in patients at risk of CINV is its convenience: the ready-to-use single oral administration of a capsule of NEPA 1 hour before chemotherapy is an assurance of correct administration of both classes of active antiemetic agents under medical supervision.

On the other hand, the use of aprepitant, FOS, or ROL is associated with a higher number of drugs to be administered to patients during the 4 days after chemotherapy (Tables 3 and 4).44–51

Table 3.

Number of doses of antiemetic drugs required for the prophylaxis of CINV for patients with cancer receiving HEC

| Chemotherapy regimen | Antiemetic regimen | References | Antiemetic drug | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | N of doses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEC | NEPA + DEX | 38 | NEPA | X | 5 | ||||

| DEX | X | X | X | X | |||||

| HEC | APR + 5-HT3-RA + DEX | 45,46 | APR | X | X | X | 8 | ||

| Ondansetrona | X | ||||||||

| DEX | X | X | X | X | |||||

| HEC | FOS + 5-HT3-RA + DEX | 48 | FOS | X | 8 | ||||

| Granisetron | X | ||||||||

| DEX | X | X | XX | XX | |||||

| HEC | ROL + 5-HT3-RA + DEX | 50 | ROL | XX | 10 | ||||

| Granisetron | X | ||||||||

| DEX | X | XX | XX | XX |

Notes: Calculations of number of doses are based on pivotal studies of approved NK1-RAs.38,45,46,48,50

In both pivotal studies, ondansetron has been administered as a single 32 mg/iv dose. Actually, due to safety concerns (QT prolongation), this dosage should be split into three different doses (16 mg, 8 mg, 8 mg) during the first day of chemotherapy, according to ondansetron summary of product characteristics.

Abbreviations: APR, aprepitant; CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; DEX, dexamethasone; FOS, fosaprepitant; HEC, highly emetogenic chemotherapy; 5-HT3-RA, 5-HT3 receptor antagonist; iv, intravenous; N, number; NEPA, netupitant/palonosetron; NK1-RAs, NK1 receptor antagonists; QT, name for the measure of time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave on an electrocardiogram; ROL, rolapitant.

Table 4.

Number of doses of antiemetic drugs required for the prophylaxis of CINV in patients receiving MEC

| Chemotherapy regimen | Antiemetic regimen | References | Antiemetic drug | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | N of doses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEC-AC | NEPA + DEX | 39,44 | NEPA | X | 2 | ||||

| MEC non-AC | DEX | X | |||||||

| MEC-AC | APR + 5-HT3-RA + DEX | 40,47 | APR | X | X | X | 5 | ||

| MEC non-AC | Ondansetron | X | |||||||

| DEX | X | ||||||||

| MEC non-ACa | FOS + 5-HT3-RA + DEX | 49 | FOS | X | 3 | ||||

| Granisetron | X | ||||||||

| DEX | X | ||||||||

| MEC-AC | ROL + 5-HT3-RA + DEX | 51 | ROL | XX | 8 | ||||

| MEC non-AC | Granisetron | X | XX | XX | |||||

| DEX | X |

Notes: Calculations of number of doses are based on pivotal studies of approved NK1-RAs.39,40,44,47,49,51

Only non-AC, MEC study is available for FOS.

Abbreviations: AC, anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide; APR, aprepitant; CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; DEX, dexamethasone; FOS, fosaprepitant; 5-HT3-RA, 5-HT3 receptor antagonist; MEC, moderately emetogenic chemotherapy; N, number; NEPA, netupitant/palonosetron; NK1-RAs, NK1 receptor antagonists; ROL, rolapitant.

Finally, NEPA is effective and safe in both HEC and MEC and simplifies the therapy by reducing the number of single drug administrations needed, guaranteeing adherence to antiemetic guidelines, and consequently improving the control of CINV. Moreover, providing an effective antiemetic regimen, NEPA, may improve patient adherence to the chemotherapy regimen prescribed and foster completion of treatment.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Middleton J, Lennan E. Effectively managing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Br J Nurs. 2011;20(17):S7–S8. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.Sup10.S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson N. Optimizing treatment outcomes in patients at risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(3):309–313. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grunberg SM, Slusher B, Rugo HS. Emerging treatments in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2013;11(2 suppl 1):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. ESMO/MASCC Guidelines Working Group Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 5):v232–v243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basch E, Prestrud AA, Hesketh PJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(31):4189–4198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) [webpage on the Internet] Antiemetic Guidelines V2.2015. [Accessed January 11, 2016]. issued on 22 September 2015. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf.

- 7.Natale JJ. Reviewing current and emerging antiemetics for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. Hosp Pract (1995) 2015;43(4):226–234. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2015.1077095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rojas C, Slusher B. Pharmacological mechanisms of 5-HT3 an tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonism to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;684(1–3):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorusso V, Karthaus M, Aapro M. Review of oral fixed-dose combination netupitant and palonosetron (NEPA) for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Future Oncol. 2015;11(4):565–577. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navari RM. 5-HT3 receptors as important mediators of nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848(10 pt B):2738–2746. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navari RM. Palonosetron for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(17):2599–2608. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.972366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, et al. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(10):1570–1577. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenberg P, Figueroa-Vadillo J, Zamora R, et al. Improved prevention of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with palonosetron, a pharmacologically novel 5-HT3 receptor antagonist: results of a phase III, single-dose trial versus dolasetron. Cancer. 2003;98(11):2473–2482. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, et al. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celio L, Niger M, Ricchini F, Agustoni F. Palonosetron in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: an evidence-based review of safety, efficacy, and place in therapy. Core Evid. 2015;10:75–87. doi: 10.2147/CE.S65555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morganroth J, Parisi S, Spinelli T, Moresino C, Thorn M, Cullen MT. High dose palonosetron does not alter ECG parameters including QTc interval in healthy subjects: results of a dose-response, double-blind, randomized, parallel E14 study of palonosetron vs moxifloxacin or placebo; 14th ECCO; 23–27 September 2007; Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dogan U, Yavas G, Tekinalp M, Yavas C, Ata OY, Ozdemir K. Evaluation of the acute effect of palonosetron on transmural dispersion of myocardial repolarization. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(4):462–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yavas C, Dogan U, Yavas G, Araz M, Ata OY. Acute effect of palonosetron on electrocardiographic parameters in cancer patients: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(10):2343–2347. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonullu G, Demircan S, Demirag MK, Erdem D, Yucel I. Electrocardiographic findings of palonosetron in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(7):1435–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aapro M, Carides A, Rapoport BL, Schmoll HJ, Zhang L, Warr D. Aprepitant and fosaprepitant: a 10-year review of efficacy and safety. Oncologist. 2015;20(4):450–458. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojas C, Slusher BS. Mechanisms and latest clinical studies of new NK1 receptor antagonists for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: rolapitant and NEPA (netupitant/palonosetron) Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(10):904–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leal AD, Kadakia KC, Looker S, et al. Fosaprepitant-induced phlebitis: a focus on patients receiving doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(5):1313–1317. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundberg JD, Crawford BS, Phillips G, Berger MJ, Wesolowski R. Incidence of infusion-site reactions associated with peripheral intravenous administration of fosaprepitant. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(6):1461–1466. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2106-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujii T, Nishimura N, Urayama KJ, et al. Differential impact of fosaprepitant on infusion site adverse events between cisplatin- and anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(1):379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syed YY. Rolapitant: first global approval. Drugs. 2015;75:1941–1945. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA [webpage on the Internet] Summary of Product Characteristics of Varubi (rolapitant) [Accessed January 11, 2016]. Revised version: 09/2015. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206500s000lbl.pdf.

- 27.Errico A. Chemotherapy: NEPA-a single oral dose providing effective prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(7):377. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rojas C, Raje M, Tsukamoto T, Slusher BS. Molecular mechanisms of 5-HT(3) and NK(1) receptor antagonists in prevention of emesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;722:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas AG, Stathis M, Rojas C, Slusher BS. Netupitant and palonosetron trigger NK1 receptor internalization in NG108-15 cells. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232(8):2637–2644. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4017-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.EMA [webpage on the Internet] Summary of Product Characteristics of NEPA®. [Accessed January 11, 2016]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003728/WC500188432.pdf.

- 31.Lyman GH, Bohlke K, Khorana AA, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update 2014. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):654–656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan K, Jahn F, Aapro M. Recent developments in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a comprehensive review. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(6):1081–1090. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warr D. Prognostic factors for chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;722:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dranitsaris G, Mazzarello S, Smith S, Vandermeer L, Bouganim N, Clemons M. Measuring the impact of guideline-based antiemetic therapy on nausea and vomiting control in breast cancer patients with multiple risk factors. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(4):1563–1569. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2944-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.EMA [webpage on the Internet] Summary of Product Characteristics of IVEmend. [Accessed January 11, 2016]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000743/WC500037153.pdf.

- 36.EMA [webpage on the Internet] Summary of Product Characteristics of Emend. [Access January 11, 2016]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000527/WC500026537.pdf.

- 37.Aapro M, Molassiotis A, Dicato M, et al. PEER Investigators The effect of guideline-consistent antiemetic therapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): the Pan European Emesis Registry (PEER) Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):1986–1992. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hesketh PJ, Rossi G, Rizzi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of NEPA, an oral combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized dose-ranging pivotal study. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(7):1340–1346. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aapro M, Rugo H, Rossi G, et al. A randomized phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of NEPA, a fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(7):1328–1333. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warr DG, Hesketh PJ, Gralla RJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2822–2830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah RR. Drugs, QTc interval prolongation and final ICH E14 guideline: an important milestone with challenges ahead. Drug Saf. 2005;28(11):1009–1028. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spinelli T, Moresino C, Baumann S, Timmer W, Schultz A. Effects of combined netupitant and palonosetron (NEPA), a cancer supportive care antiemetic, on the ECG of healthy subjects: an ICH E14 thorough QT trial. Springerplus. 2014;3:389. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.EMA [webpage on the Internet] NEPA Public Assessment Report (EPAR-EMA) [Accessed January 11, 2016]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/003728/WC500188434.pdf.

- 44.Gralla RJ, Bosnjak SM, Hontsa A, et al. A phase III study evaluating the safety and efficacy of NEPA, a fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting over repeated cycles of chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(7):1333–1339. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD, et al. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer. 2003;97(12):3090–3098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hesketh PJ, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, et al. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin – the Aprepitant Protocol 052 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4112–4119. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rapoport BL, Jordan K, Boice JA, et al. Aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with a broad range of moderately emetogenic chemotherapies and tumor types: a randomized, double-blind study. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(4):423–431. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grunberg S, Chua D, Maru A, et al. Single-dose fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with cisplatin therapy: randomized, double-blind study protocol – EASE. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(11):1495–1501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinstein C, Jordan K, Green SA, et al. Single-dose fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a randomized, double-blind phase III trial†. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(1):172–178. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rapoport BL, Chasen MR, Gridelli C, et al. Safety and efficacy of rolapitant for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after administration of cisplatin-based highly emetogenic chemotherapy in patients with cancer: two randomised, active-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartzberg LS, Modiano MR, Rapoport BL, et al. Safety and efficacy of rolapitant for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after administration of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy or anthracycline and cyclophosphamide regimens in patients with cancer: a randomised, active-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]