Abstract

This paper evaluates how physicians use scientific and other forms of knowledge in different professional communities. We argue that because physicians will draw upon clinical research findings to improve their reputation with colleagues, and since the terms for accruing esteem in an academic hospital may differ depending on the dominant task structure of the organization, the form of knowledge that is therefore valued by physicians will vary with their hospital’s level of prestige. Social network and multivariate analyses are used to test this theory in six U.S. hospitals with varying levels of prestige. We find that in lower-prestige hospitals physicians can improve their reputation by reading a relatively broad range of scientific journals, whereas in higher-prestige hospitals esteem is allocated to those with a more elite medical school pedigree. Statistically significant differences also exist between hospitals in terms of whether work with patients is valued, with physicians who engage in more clinical activity in the highest-ranked hospitals receiving less esteem from their colleagues. We finish by discussing how the functioning of higher and lower prestige hospitals are interconnected in ways that sustain both the development of innovations and their widespread adoption.

Keywords: medicine, organizations, physicians, professions, social networks

Physicians are expected by patients to provide diagnoses and treatments that are based on scientific research. However, studies of how medical knowledge is shared and applied suggest that practitioners seeking this goal will experience two conflicting influences. On the one hand, physicians feel they must treat the patient in a way that reflects innovations in the scientific community, and sociologists have closely documented the uncertainty that accompanies their attempts at reaching this ideal (Parsons 1951; Fox 1959). On the other hand, physicians orient their behavior toward their colleagues at work and depend on one another to determine what is wrong with a patient, what can be done, and what should be done (Merton 1957; Becker et al. 1961; Bosk 1980).

Academic hospitals are a setting in which physicians most acutely confront this problem of embeddedness. Patients come to these centers with the expectation that they will be treated according to the latest medical research, as such hospitals widely advertise their physicians’ capacity to innovate in addressing the most challenging cases. Physicians in these centers are likely to participate in rituals (e.g., Grand Rounds and Mortality and Morbidity conferences) in which they learn new interventions to use with patients, analyze day-to-day diagnostic and therapeutic decisions, and engage in informal information exchange and collective decision-making processes (Bosk 1979; Anspach 1993; Jin 2005). These conferences often focus on a difficult case a professional has encountered in the hospital and are presented in the “n of 1” narrative structure (e.g., Hunter 1991). While such conferences may promote the translation of valuable new knowledge into practice, the fact that the problems discussed are solved by respected colleagues may also lead physicians to internalize local practice standards regardless of whether these standards are supported by the scientific literature. Given what we know about the importance of reputation in physicians’ decision making, then, it is not surprising that recent reports on “evidence-based medicine” from the medical community emphasize the unclear links in how scientific evidence is generated, diffused, and applied (Institute of Medicine 2000). It also follows that healthcare provision widely varies across organizations and regions (Wennberg 1999). Hospitals each contain their own social structures of reputation and expertise that influence how medicine is practiced, regardless of the guidelines and scientific research in a field.

To examine how this problem is overcome, this paper examines the behaviors and characteristics of physicians in higher- and lower-prestige academic hospitals that are associated with how esteem is cultivated. Such study of social status and people’s “ardor to be talked about,” their desire for reputation and honor, reaches at least as far back as Rousseau (1755). We define esteem as the evaluation of an individual’s relative performance of the tasks of a particular status position. Esteem is an important concept in a time when professional work is performed primarily in large organizations with high degrees of specialization and interdependence (Heinz et al. 2005). In medicine, physicians discuss their patients in collective and one-on-one exchanges and highly value each other’s advice and assistance. If one physician asks a colleague’s advice, this reflects the colleague’s strong reputation in this setting and claim to deference. These advice requests are desired because they will allow that physician to be able to elicit others’ assistance later (Blau 1955; Goode 1978). Furthermore, physicians seek colleagues’ recognition because it signifies that they are excelling in an activity that distinguishes their profession from others and thereby helps it retain control over its work jurisdiction (Abbott 1988). As inducement and reward, then, colleagues care about their reputation, regardless of their profession. But the importance that physicians, in particular, place on their relative standing in their workplace makes the study of esteem crucial in explaining how they are likely to use a new scientific finding or change their practice in other ways.

The dominant criteria that determine a physician’s esteem are likely to vary depending on the relative prestige level of his or her organization. This is because the dominant tasks of physicians vary according to their hospital’s prestige level. For example, prestigious academic hospitals attract patients with rare conditions, and their physicians also receive recognition for their research. Those hospitals may differ from lower-prestige hospitals across multiple other dimensions: the extent to which physicians value risk taking, the types of jobs sought by students being trained, and the amount physicians appreciate the importance of clinical tasks. Therefore, to capture the extent to which accessing scientific information is valued, we must identify how a physician gains esteem for allocating his time to accessing this information and compare the importance of this practice relative to other characteristics that might generate respect in the workplace, such as experience, medical school prestige, subspecialization, or amount of time allocated to clinical work.

Medical research on physicians’ decision making with patients has shown that doctors differ widely in the way they access, interpret, and apply clinical research findings. Yet these differences can also be understood by switching one’s perspective to consider evidence-based medicine as an act influenced by a physician’s colleagues as much as his patients. By doing so we contribute to recent research that has reexamined the interrelations between the medical profession and its bureaucratic contexts (Hafferty and Light 1995; Scott et al. 2000; Leicht and Fennel 2001), “evidence-based medicine” (Timmermans and Angell 2001), and we also extend recent efforts to account for and evaluate the effects of intra-professional stratification in medicine (Hoff 1999; Menchik and Jin 2006). By developing and testing a theory that links physicians’ reputations in the workplace to the position of their hospital in the medical system, we can also begin to build an empirical base for a theory of professional esteem more generally.

EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE AND PHYSICIAN ESTEEM

In this section we develop a theory of the relationship between physicians’ pursuit of scientific knowledge and their hospitals’ pursuit of prestige. Although many studies emphasize that physicians retrieve journal-based knowledge solely to treat their patients, we suggest they are also driven by the desire to be esteemed by their colleagues. A consequence of this is that the personal characteristics that drive physicians’ adoption of knowledge will also differ according to characteristics of the hospital in which they work. After arguing below that few studies demonstrate the factors that mobilize physicians’ use of new information, we show how the study of esteem can expose the relationship between the prestige of an organization and the pursuit of knowledge, and extend some relevant research questions.

The problem of evidence-based medicine

Even though basing medical care upon scientific grounds has historically underpinned physicians’ collective claim to authority (Freidson 1970; Starr 1982), the type of knowledge individual physicians use differs widely. Despite or due to this variation, a social movement and set of institutional pressures, emanating especially from researchers, have recently formed that strongly urges physicians to improve their ability to integrate their field’s most recent scientific findings into practice (Pope 2003). The concept of evidence-based medicine is usually framed as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (Sackett and Rosenberg 1995). Proponents of evidence-based medicine claim all physicians will improve their performance by searching and evaluating literature when they have questions about clinical diagnosis, prognosis, or management (Strauss and McAlister 2002). Although some members of the profession argue that the basic assumptions of the evidence-based medicine movement have been unproven and largely untested (British Medical Journal 2005), the movement’s central principles have received considerable attention; medical schools teach them, advocates continuously redefine them, and journals host debates on their merits. These scientific journals have been the primary locus for discussion and research around the application of scientific knowledge in practice; the number of articles with “evidence-based medicine” as a subject in the Medline database increased from 3 in 1993 to approximately 2,750 in 2003 (Jin 2005). While there is an obvious motivation for journals to encourage discussion on this particular subject of professional interest, the level of attention is similar to that of other institutions that have incorporated scientific findings into their processes of regulation. Managed care organizations develop physician practice guidelines based on clinical research findings and recommendations, and many federal “pay for performance” programs are beginning to make physicians’ compensation contingent on following these recommendations. Such knowledge even forms a standard that may be used in deciding whether physicians are culpable in malpractice proceedings (Hyams, Shapiro, and Brennan 1996).

On the social scientific side, we know a great deal about the resistance to evidence-based medicine with individual patients (e.g., Berkwits 1998; Armstrong 2002; Mykhalovskiy and Weir 2004). There are conflicting scientific findings on diverse subjects – from the use of beta blockers, to prostate cancer treatment, to hormone replacement therapy.1 Physician and patient decisions regarding these treatments are governed by quality-of-life concerns as much as by trial results. Physicians have limited time.2 Particular research methods, types of data, and approaches to analysis are considered rigorous by some, unconvincing by others. The contexts in which a study was designed may appear incompatible with those in which it will be applied. Finally, physicians may not believe the profile of patients in their workplace fits the profile of those used in the randomized clinical trial. These studies often conclude by contrasting the “art” of experience and embodied knowledge with the “science” of research findings, and they emphasize how the former type of knowledge trumps the latter in decision making.

Medical researchers’ studies of the actual use of scientific findings often attempt to isolate the specific effects of accessing new knowledge upon a physician’s practice. Yet they do not focus on the importance of personal characteristics and the behaviors of individual physicians, nor do they examine the salient pressures at work, considering instead the size of the group exposed to research findings and the country of origin of physicians using electronic tools (Smeele et al. 1999; Lagerlov et al. 2000). A further problem is that these studies emerge from relatively controlled circumstances that do not always reflect relevant pressures of career advancement and of patient care, examining physicians in detachment from others in their context. Researchers focus upon characteristics of the physician, such as gender, number of years since graduate school, and age, or the subjects that physicians use electronic resources to access. In these studies the little background information gathered is not used for explanation, but rather as a set of controls in assessing the independent effect of an educational intervention. Thus we know little about the use of scientific knowledge outside of controlled experimental conditions.

Despite previous work on the contemporary salience of evidence-based medicine in the profession of medicine, physicians’ uneven use of scientific evidence with their patients, and researchers’ attempts to change behavior, we still know little of the factors explaining why physicians retrieve knowledge in the first place. One way to see how evidence is valued in practice is to focus less on the way knowledge is consumed solely for patient treatment. Professionals care about their reputations, and the fact that they are normatively expected to advise their colleagues means that, in some circumstances, they may draw on this scientific literature in order to improve their reputations. The existence of fundamental uncertainties surrounding the application of this knowledge further strengthens this possibility. In the next sections we introduce the concept of esteem and describe how its underpinnings emerge through comparisons among colleagues.

Organizations and Esteem

Professionals consult with others they hold in high regard, and they want this recognition from colleagues for themselves. Because certain behaviors and characteristics of respected colleagues reflect – and concomitantly reinforce – the normative standards among a set of professionals with similar tasks, understanding how professionals are perceived in the workplace may be an important step in understanding the practices in which they engage.

Sociologists have long shown that people are motivated by status, prestige, and deference (Goldhamer and Shils 1939; Shils 1968; Goode 1978; Coleman 1990; Becker, Murphy, and Werning 2005). Recent research on influence systems has advanced our general understanding of status acquisition, demonstrating how individuals and their social groups allocate status depending on conclusions about nominal characteristics such as race or gender (Ridgeway 1991), capabilities in interaction (Ridgeway and Erickson 2000), and endorsements by trusted third parties (Podolny 2001; Gould 2002; Martin 2005; Berger and Fişek 2006). These studies show that when interactants are goal oriented, they develop guesses about others’ competence by watching their performance of the task at hand, concluding, for example, that an individual with notable wit, intelligence, or another valued resource is also representative of others who share characteristics with that individual. Further, we know that status acquisition also brings generalized power to a person who is perceived to have a relatively higher standing than others sharing his or her role (Coleman 1990). Consequently, status becomes convertible; once perceived as having high status, individuals can then hold forth on topics that may be of only marginal relation to the aspect of their identity initially responsible for improving their reputation, leading to wide-ranging influence (Parsons 1963).

Across workplaces we can expect that the terms for this local status, or what we call esteem, will vary. To develop the concept of esteem we focus upon a particular continuum within Goldhamer and Shils’s (1939) measure of status. This measure depends on the individual making a “status judgment” and on her knowledge of the characteristics of the person being judged. The person making the judgment has a set “hierarchy of values,” and the person to whom she assigns status exemplifies her most important value. If a person who ranks integrity high in her hierarchy of values feels a particular Supreme Court justice, for example, has a high level of integrity, she will grant that Supreme Court justice high social status. We argue that values underpinning esteem in an organization center around the tasks that must be performed by a group of practitioners. Studies of both medical and non-medical professionals have shown grounds for collegial control to be based on these tasks, as the control over the application of specialized expertise distinguishes a set of experts both from members of other professions and from the lay community at large (Freidson 1970; Abbott 1988; Mather, McEwen, and Maiman 2001). Based on this research, then, our definition of professional esteem assumes that performance on these tasks is at the apex of the hierarchy of values as described by Goldhamer and Shils and will therefore define the terms upon which a professional will evaluate her colleagues at work.

Although capturing the dynamics of esteem carries both theoretical and practical implications for understanding changes in professional practice in an organization, relatively little is known about how esteem is gained and lost in these contexts. Processes through which status is allocated across the legal profession have been studied extensively (e.g., Abbott 1981; Heinz and Laumann 1982; Sandefur 2001; Heinz et al. 2005). In addition, Shortell (1974) conducted an important analysis of status differences across members of medical subspecialties. Prestige is the respect that one receives from society in general (Goode 1978), and the seminal study of prestige in occupations remains Blau and Duncan (1967).

We have shown how recent studies of status strengthen our assumption that certain esteemed physicians specializing in internal medicine will motivate the behavior of their peers and also reinforce the value of studying these individuals to understanding the acquisition of scientific findings. In the next section we narrow our purview to arrive at research questions that explore the origins of this esteem and specifically connect its study in a hospital to a way of understanding the knowledge its doctors value.

Esteem within and between academic hospitals

Our analysis begins by examining the knowledge-related underpinnings of esteem across all of the hospitals in our sample and then focuses on how these differ for hospitals with varying levels of prestige. As discussed above, the normative expectation of physicians in an academic setting is that they give advice in everyday interactions. Yet there is some ambiguity as to the optimal type of advice provided; we do not know if the expertise that is valued will be of the evidence- or experience-based variety. We do not know if it will originate in experience working with the hospital’s usual patient base, or whether it stems from extra years of specialized training within internal medicine. This leads us to inquire into the terms for esteem in general: Are physicians more likely to value knowledge extracted from scientific resources, subspecialty training, experience in a common hospital, or frequent hands-on work with patients?

We also consider how these terms for esteem vary among academic hospitals with different levels of prestige. The literature on medical care and organizational prestige demonstrates that tasks in a hospital or any organization will vary depending on the community of patients served (Freidson 1960; Croog and Ver Steeg 1963; Kaluzny and Shortell 2006). Yet although all organizations depend on their environment for resources, higher-prestige organizations are able to better control this dependence (Perrow 1967), and thus might be able to focus on tasks involving research and discovery. Combining this work, then, leads us to the following question: how does the knowledge valued by physicians in a certain organization depend on factors that vary with the organization’s prestige?

DATA, METHODS AND MEASURES

Our data contain three principal features that make them unique for examining how scientific findings enter a professional setting. First, the survey (the Multicenter Trial of Academic Hospitalists) was distributed between July 2001 and June 2003 to all physicians working on the general medicine services at six U.S. academic medical centers of varying sizes and geographic locations and yielded a response rate of 69 percent (N=281). Whereas previous studies of scientific resources examined only one practice setting, our use of multiple hospitals allows for comparison across different organizations. Second, rather than being geared to the study of one particular question, the data questionnaire addresses several ways in which physicians gather information and interact. As the data contain extensive background information on respondents (including age, gender, experience in a hospital, medical school, percentage of time allocated to patient care, and subspecialization), they afford the possibility to take confounding influences into account. Third, the social network measure we develop to evaluate esteem can reveal potential channels through which information will flow in hospitals and specify the physicians facilitating its initial entrance.

Our definition of esteem requires that we study those who share a particular organizational role. Given the diversity of potential jobs in a hospital for those with a medical degree, in our data analysis we must specifically hold constant in our data analysis the standard against which one person judges another, assuming it to be shared among a set of individuals who engage in one type of professional task for similar amounts of time. Physicians must share a set of work tasks in order for their judgments of each other’s professional reputation to be considered commensurable; it is not useful to study the underpinnings of professional esteem in a community of professionals by comparing a full-time administrator with a full-time clinician, irrespective of common training. We thus restrict our analysis to the 126 physicians in our sample who spend on average at least 30 percent of their time in clinical work per month.3 In doing so we select approximately 45 percent of each department, an amount that provides us with a relatively reliable and stable measure of in-degree centrality (Costenbader and Valente 2003; Zemljica and Hlebecb 2005). After comparing the selected and missing physicians using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, we find those excluded in all settings have significantly lower esteem levels, a degree of relative marginalization that suggests they will be only minimally important for understanding the standard-setting actors in a department.

We developed our measure of esteem through the use of two work-related questions based on the Coleman, Katz, and Menzel (1966) study of the diffusion of tetracycline among physicians in four Illinois towns: “To what three attending physicians do you most often turn for advice and information?” and “With what three attending physicians do you most often discuss your cases in the course of an ordinary month?” Although the questions will likely restrict the possible set of physicians chosen to those considered accessible (and thus undersample intimidatingly exemplary individuals in an esteem hierarchy), our approach has an advantage over the ways of measuring workplace esteem that simply survey attitudes. Reports of past behavior signify a commitment on the part of the nominator, rather than preferences, ideals, or intentions. Further, those nominated are more likely to share tasks with the physicians who nominate them, an important condition for validity in our measure of esteem. These evaluations thus represent the presence and operation of what is thought to be of ultimate and determinative significance in a particular context. They also identify the power of the frequently nominated – those who nominate a physician are predisposed to comply with this individual’s advice before assistance is delivered (Blau 1955).

Social network analysis is used in our study to measure esteem. Our approach resonates with our colleagues’ use of network analysis to study health-related advice (e.g., Pescosolido 1992; Christakis 2000), knowledge diffusion among physicians (e.g., Coleman et al. 1966; Burt 1987), and the sentiments of an interdependent population of professionals (e.g., Scott 1961; Kim and Laumann 2003). Our relational measure of the esteem of individual i in hospital j (Cij) is a basic count of the number of colleagues who have claimed they most often choose that individual for clinical advice in the course of caring for patients hospitalized on the general medicine services. Specifically, we use in-degree centrality (Freeman 1979: 219), adjusted for the population size (the number of general medicine physicians at each hospital). This is the summation over all colleagues who choose individual i. Tkij=1 if individual i in hospital j is chosen by colleague k, and zero otherwise. The amount is then normalized in relation to the number of respondents in the individual’s hospital (Nj).

To determine whether esteem acquisition differs between organizations, we divide the six hospitals into two categories: higher and lower prestige. It is problematic to accurately assess a hospital’s overall reputation, because many have strengths concentrated in certain subspecialties. We thus developed our ranking by using the U.S. News and World Report’s “Honor Roll,” which lists the 17 hospitals with high scores in at least three sets of subspecialty rankings (2007).4 Since the three lower-prestige hospitals we studied were not in the top 16, we used the same publication’s medical school rankings (2007) to complete the list.5 In dividing the hospitals into two categories we were also able to align hospital reputations with rankings on another scale of prestige, related to the total funding allocated by the National Institutes of Health. Finally, our rankings were consistent with the only sociological study of medical school prestige of which we were aware, that of Cole and Lipton (1977). Table 1 illustrates how the six hospitals differ according to size, distance patients travel for care, complexity of patient base, research focus, and level of prestige.

Table 1.

Differences in Catchment Area, Research Focus, and Reputation Across Higher- and Lower-prestige Hospitals

| Hospitals (Means)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Higher Prestige | Lower Prestige | |

| Size (number of beds) | 636 | 542 |

| Percentage local patients* | 20.03% | 30.30% |

| Transplant services | 4.33 | 3.33 |

|

| ||

| NIH overall funding ranking (Ranked to 121) | 18.67 | 42.67 |

| NIH awards funding (2003) | $226,125,786 | $109,894,460 |

| NIH research funding (2003) | $198,764,726 | $92,723,509 |

|

| ||

| US News overall medical school ranking (100=best) | 88.5 | 73.5 |

| US News peer assessment medical school rank (5.0=best) | 4.5 | 3.65 |

| US News Honor Roll ranking (Top 17 hospitals) | 11.34 | Unranked |

| US News number of specialties ranked in top 50 | 13 | 6.5 |

= percent of patients from three closest zip codes that go to that hospital for treatment. Sources: American Hospital Directory, NIH 2003 Funding, US News & World Report

We also account for the differences in the way physicians may engage with the medical literature. Organizational sociologists have recently paid more attention to the forms and the extent of distribution of information in firms, identifying what have been called “information regimes” (e.g., Moldoveanu, Baum, and Rowley 2002; Stovel and Fountain 2006). The first information regime we examine involves using Medline (the tool most frequently used by physicians to search for findings [Bennett et al. 2004]), or another computer-based tool to search the medical literature based on specific keywords. The second involves reading across different medical journals. To measure these two information regimes we ask how many times respondents “performed a Medline or other computer-based literature search” during an average month and also the “number of journals [they] read regularly.” It is interesting to note the extremely low correlation (.08) we find between a physician’s level of Medline use and the breadth of journals he reads.

The physicians vary with regard to several characteristics that index the varieties of knowledge we discussed in the introduction and questions above. Experience in a setting of colleagues was measured by asking physicians how many years they had practiced in their current hospitals.6 We chose to include experience and exclude age in the regression due to the high correlation between these two variables (0.78), and the similar effects of either variable in the regression results. The experience variable also best accounts for common site-based knowledge. The prestige of the physician’s medical school was measured according to U.S. News and World Report’s “peer-review” rankings, which range from 1 to 5 (lowest-highest). The dummy category of “subspecialist” was created for physicians who indicated they had received training in internal medicine subspecialties (e.g., endocrinology, geriatrics, or infectious diseases). The proportion of time a physician spends doing clinical work was gathered by combining the percentages of total work time per week engaged in inpatient service, consultant work, and ambulatory care.

To assess physician characteristics that have the greatest influence on esteem, we employ multivariate negative binomial regressions with and without hospital-specific fixed effects. The negative binomial is appropriate for our outcome because of the shape of the distribution and the fact that it is a countable measure. We compare regression coefficients between hospitals by dividing the difference in coefficients by the square root of the sum of the two squared standard errors (Clogg, Petkova, and Haritou 1995). In our first regression we exclude fixed effects in order to explore the differences in the esteem distribution when stratifying by the prestige level of a hospital. For the remainder of the regressions we include hospital fixed effects to control for any difference across hospitals in other attributes (prestige, gender distribution, size, etc.) that we have not otherwise accounted for and could vary across hospitals and potentially confound our findings. For example, it may not be that variations in doctors’ journal readership affect esteem, but rather that esteem could be influenced by unobserved hospital characteristics that also vary by journal readership. Likewise, esteem might be driven by unobservables such as the level of patient acuity ordinarily confronted, money for attending conferences, or the presence and frequency of department rituals such as Grand Rounds where physicians can deploy knowledge and observe each other. Controlling for variation across hospitals in staffing is also important because of the possibility that some receive a high number of nominations in a hospital simply because their traits are more prevalent. Thus fixed effects are also important to ensure that nominations reflect esteem, rather than homophily, a potential alternative determinant of physicians’ nomination patterns.

RESULTS

This section describes basic differences in the hospitals we study and the characteristics and behaviors that are valued across and between physician networks. First, we present the summary statistics for the clinicians.

The most striking observation from this table is the difference across hospitals in the rates at which physicians draw from the literature. Higher-prestige hospitals house physicians who, on average, search for information using Medline five occasions more per month than those in lower-ranked hospitals. Larger standard deviations among individuals in higher-ranking hospitals also indicate a more pronounced division of labor there between high and low Medline users, suggesting a wide range between “power users” and other clinicians. For journal reading there appears also to be a division of labor in the high-prestige hospitals, although the effects are less pronounced.

There are also interesting and statistically significant differences in the types of work and career choices supported in each setting. Doctors at the higher-prestige hospital are on average four years younger and have spent four fewer years working at the hospital. This turnover rate may be attributed to the fact that more than twice as much grant funding is awarded there than in lower-ranked hospitals (Table 1.). This can likely explain why physicians in these sites devote approximately five percent less of their time devoted to clinical care.

The first model in Table 3 uses an ordinary least squares regression to show that the number of nominations by two otherwise identical doctors will receive differs across high- and low-prestige hospitals. If a physician is in a high-prestige hospital she will lose more than half of one colleague (0.61).7

Table 3.

Association of Physicians’ Information Collection Habits and Work Tasks with the Indegree Measure of Esteem

| Independent Variables: | All hospitals | Higher-prestige hospitals | Lower-prestige hospitals | t-statistic across hospital prestige groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Indegree Measure of Esteem | |||||

| Higher-Prestige Hospital | −1.363*** (−0.286) |

† | |||

| Number of journals read/month | 0.121* (0.051) |

0.113* (0.050) |

0.084 (0.047) |

0.245* (0.106) |

−1.39 |

| Number of times used Medline/month | 0.017 (0.012) |

0.013 (0.011) |

0.014 (0.012) |

0.009 (0.02) |

0.23 |

| Percent of time doing clinical work | −0.004 (0.006) |

−0.004 (0.006) |

−0.018* 0.007 |

0.013 (0.010) |

−2.45* |

| Prestige of medical school | 0.356 (0.184) |

0.452* (0.188) |

0.706*** (0.211) |

0.262 (0.321) |

1.16 |

| Experience in hospital | −0.03 (0.023) |

−0.033 (0.023) |

−0.042 (0.033) |

−0.021 (0.033) |

−0.45 |

| Subspecialist | −0.322 0.248 |

−0.4 (0.249) |

−0.583 (0.343) |

−0.391 (0.382) |

−0.37 |

| Male (=1) | 0.111 (0.244) |

0.168 (0.240) |

0.27 (0.301) |

−0.125 (0.351) |

0.85 |

| Constant | 0.675 (0.88) |

−1.24 (0.947) |

−1.592 (0.973) |

−0.817 (1.776) |

|

| Hospital fixed effects included? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 126 | 126 | 74 | 52 | |

p <.05;

p <.01;

p <.001 (two-tailed tests). Standard errors in parentheses

Fixed effects regressions do not use the dummy variable for the higher-prestige hospitals

The first model in Table 3 also indicates that, across all hospitals, those physicians who consult a greater number of journals are recipients of a higher level of esteem in the workplace. Yet with the exception of medical school prestige of individual physicians, none of the other variables are significant, and some of the variables that are not statistically significant suggest that experience and subspecialty training can lower one’s reputation. This addresses our first question above by showing that physicians are more likely to value knowledge extracted from scientific resources when this knowledge comes from reading across a range of journals.

However, it may be that the benefits of accessing scientific findings vary for physicians depending on their institutional context. We now turn to that question, introducing fixed effects to control for hospital characteristics, such as prestige. We run these regressions in the higher prestige and in the lower prestige hospitals, which allow us to essentially ask whether the association between scientific findings and esteem varies by organization.

The next three models include organization-specific fixed effects models, and show that reading across journals continues to improve one’s reputation in all hospitals. Looking closer at this valuation of journals tells a different story, however. The last two models can be interpreted as comparisons among doctors working in the same organization averaged over the three hospitals in the same prestige tier. In the third model we see that coefficients that represent journal reading diminish by approximately 0.03 and lose statistical significance in the high-prestige hospitals, suggesting that the effects in the first and second models are being driven by those hospitals in the lower echelon of the prestige distribution, for which the coefficient is large and statistically significant. Comparing the coefficients across prestige levels, we see that physicians in lower-prestige hospitals are able to gain one more colleague’s nomination for every four more journals they read, whereas physicians in high-prestige hospitals must read 12 more journals to receive one more nomination. These results provide evidence that the type of knowledge most likely to inform work in the lower end of the prestige spectrum is that extracted from reading multiple journals.

Yet interestingly, in higher-prestige hospitals it is not necessary to update one’s knowledge to improve one’s level of esteem. Here we again see the benefits of using fixed effects; since one might be concerned about a potential correlation between medical school and the prestige of one’s hospital, hospital fixed effects eliminate this potential bias from our estimates. Considering the significance of the medical school prestige variable in the higher-prestige hospitals, at first blush it seems that simply having attended an elite medical school will save a physician from having to read four journals a month. The story gets even more interesting when we compare across prestige strata, where we find the coefficient for having attended a prestigious medical school to be three times larger than in the lower-ranked hospitals. Pedigree purchases colleagues’ respect at the top but not at the bottom of the prestige order.

In these high-prestige centers the key to mobility is in reducing one’s patient load. The more time clinicians in higher-prestige hospitals allocate to patient care, the less esteem they attain. But in lower-prestige hospitals the focus on clinical work differs; here the effect of clinical work is either zero or positive. The results of a two-tailed t-test on this variable indicate the effect of conducting clinical work is significantly different between hospitals, suggesting very different appreciation of devoting oneself more intensely.

That the coefficients on the subspecialty variables are negative is also revealing of the type of expertise that is valued. Although these are not statistically significant, their negative direction and large magnitude is noteworthy. These results can be explained by the fact that all of these hospitals are academic centers where physicians are likely to think of themselves as responsible for publishing normative statements about the field. In other words, in these places it is possible to be a “pure” internist and still receive the esteem of colleagues because they act as a model to the rank and file in the community hospitals and private practice.

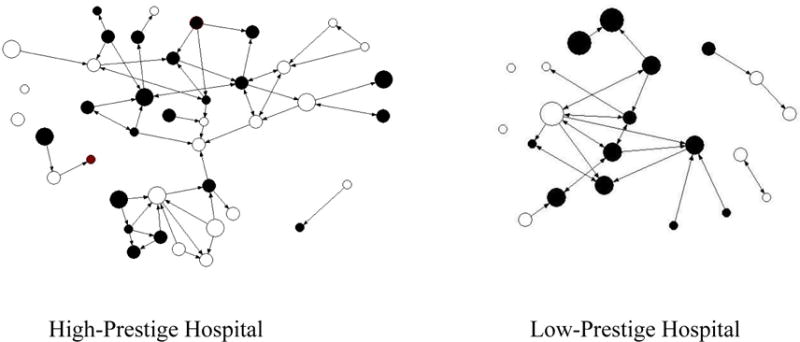

To gain an intuitive feel for the relationship between journal readership, amount of clinical work, and the distribution of esteem, consider the sociograms in Figure 1. Relations among physicians are represented by lines, with relational direction indicated by arrows, and the more highly nominated occupy more central positions. The size of the dots, or “nodes,” is scaled according to the number of journals a physician reads on a regular basis.

Figure 1. Journal Reading, Clinical Time, and the Distribution of Esteem in High- and Low-Prestige Hospitals.

Size of node is proportional to the number of different journals read by a physician.

○ = Low percentage of time spent in clinical work (the bottom half of clinicians in sample)

● = High percentage of time spent in clinical work (in the top half)

We see in these sociograms that those in the center of each hospital’s sociogram do indeed exemplify the characteristics of highly esteemed physicians reported in Table 3. In the high-prestige hospital we see that some small dots occupy the core of the discussion network, and there are many fairly large people who live on the periphery. The pattern is reversed in the lower-prestige setting, where the larger nodes receive many more nominations than the smaller ones, which are isolated on the margins of the sociogram.

Furthermore, in the lower-prestige hospital we see the centrality of those who spend a higher percentage of their time working with patients. Of the physicians cited at least three times in the low-prestige place, four out of five of them spend a high percentage of time conducting clinical work. In contrast, only three out of nine doctors in the high-prestige hospital allocate an above-average amount of time conducting clinical work.

In the higher-prestige hospitals esteem is concentrated in a handful of individuals, whereas it is distributed more evenly in the other settings. The pattern of association in the sociograms is supported by graphs of the distribution, which indicate the presence of several highly-nominated opinion leaders in each of these hospitals (available upon request).

That the largest dots have the most in-ties in the lower-prestige hospital helps strengthen the validity of our dependent variable; advisor nominations are based on one’s performance on the dominant tasks in a hospital. The relatively lower density of the low-prestige hospital network suggests that a randomly-selected doctor there will be at higher risk of using or hearing about an innovation more quickly.

Considering data in the tables and the figure, then, our assumption that esteem is tied to task structure is supported. At top places the focus is on removing doctors from the clinic so they can cash in on their pedigree by speaking at conferences and Grand Rounds and by publishing. Money to support the hospital comes in through grants. In the low-prestige centers the esteemed physicians sustain the patient base of the hospital by bringing in clinical dollars, and read across journals when treating these patients. In the final section we discuss the potential interconnection mediating the relationships between hospitals with these different task structures.

DISCUSSION

That terms for accruing esteem vary according to hospital prestige levels points towards two different logics for the entrance of knowledge into each type of organization. Physicians are likely to read a wider range of journals in the lower-prestige places. In the higher-prestige hospitals the valued currency is diminished, or at least selective, engagement in clinical work. Below we suggest how the different approaches to the use of knowledge support a division of labor with respect to knowledge use and production across organizations, and discuss the consequences of our findings for the understanding of intra-professional stratification.

The logic of organizational prestige and knowledge use suggests the existence of two “knowledge strata.” There is a statistically significant difference in the percentages of people with degrees from high-prestige medical schools in the higher- and lower-ranked hospitals. Based on our regression analyses, in the former set of hospitals the individuals with these high-prestige degrees are likely the ones attending conferences and being listened to by their colleagues. Influential people in the top hospitals, then, may tend to create and reinforce the adoption of knowledge developed and diffused in the high-prestige schools. In the bottom-ranked hospitals physicians value ideas derived from cross-journal reading. They are likely the consumers of the knowledge created at the top of the field. Our findings thus suggest the two organizational strata are interconnected in ways that sustain both the development of innovations and their widespread adoption.

This interdependence prompts another question: what then is the importance of interaction with patients? Although our data emphasizes professional dynamics of control, our findings also suggest how physicians’ work in accessing knowledge in low-prestige hospitals is required due to needs of its physicians for assistance in managing patients who independently retrieve health information. Lower-ranked hospitals have patients whose problems are more commonplace and who can thus feel able to be reasonably informed on, and confident intervening in the treatment of, their medical condition. It has long been the case that patients frequently access information through their social networks and by reviewing newspaper articles and television advertisements. More recently, websites and internet discussion groups are becoming a source of patient information. Here patients access clinical trials and innovative treatments advertised by pharmaceutical companies. Some argue that eased patient access to medical information will weaken physicians’ professional legitimacy (e.g., Hardey 1999; Nwosu and Cox 2000; Powell and Clarke 2002). Since patients often bring this information to the attention of their physicians, the opinion leaders in the clinic may thus be esteemed on the basis of their capacity to assist colleagues in asserting their authority with patients. Contrary to the way evidence-based medicine is often framed, then, physicians in lower-ranked hospitals may access increasingly technical scientific reports to bolster their recommendations and maintain clinical authority with patients who believe they have the capacity to develop expertise. In other words, evidence-based medicine might be used to move to a higher level of abstraction in order to preserve distance from these patients during clinical interactions and thus ensure that the knowledge used will be that which is created by their colleagues in the higher-prestige centers.

The results also offer insight into opportunities for mobility within an academic hospital. Given that the strongest source of esteem in the prestigious hospitals comes from the pedigree of a physician’s medical school, it is difficult to overcome deficits in such settings. There, esteem is largely ascribed, although it might be marginally raised by avoiding clinical work. In lower-ranked schools, those who have high levels of medical school prestige may carry the stigma of having underachieved relative to similarly-trained peers. Their capacity to improve their reputation may suffer from this potential loss of credibility. At the same time, mobility in lower-prestige hospitals may be more fluid since reading more journals is a goal that can be reached through effort and interest.

Other findings point toward the value of studying interactional factors to understand the use of knowledge, and indeed, suggest the initial puzzle focusing on local esteem and outside knowledge should be reframed. Since esteem is bound to doing the right amount of clinical work for one’s hospital, it may be fruitful to investigate whether and how scientific findings might be used by physicians to reinforce the strength of collegial relationships, especially in lower-ranked institutions. Because of the range of findings on any issue, it is possible that those who access research findings occupy a position from which they reassure colleagues that existing normative standards for practice are supported by the “scientific community.” And because the very existence of an evidence-based medicine movement suggests the contemporary unwillingness of many physicians to generalize across contexts, the information-seeking division of labor may facilitate physicians’ advice to colleagues that findings on a given topic are inconclusive. Their claims could be that their own and the trial’s patient populations are incommensurable or simply that the conditions of the hospital are inadequate to address a patient’s problem in a fashion that is fully in line with recommendations stemming from research findings. This is especially possible in lower-prestige hospitals, where clinical time is valued, as are relationships with colleagues who read multiple journals. Paradoxically, then, for some settings an emphasis upon evidence-based medicine could result in a strengthening of clinically produced information, a means through which local standards become warranted claims.

Our findings suggest other, more general lessons for the study of evidence-based medicine and practice variation. The reputational returns to journal reading suggest that the kind of evidence-based medicine advocated by researchers and discussed above is more likely to be employed at the lower end of the prestige spectrum. In particular, our findings suggest we should question the strong assumption stemming from medical sociology that the value of this knowledge should always be subordinate to forms involving personal experience (e.g., Miller 1970; Stelling and Bucher 1972). Experience does not seem to be important in either high- or low-prestige hospitals, and we see that in high-prestige hospitals a physician will be penalized by his colleagues the more time he spends in activities like clinical work. Thus, in some settings, resistance to a model of medicine informed solely by clinical encounters may actually increase the standing of a young physician. Therefore it is crucial to consider doctors’ contexts to understand whether characteristics we think of as “professional” in nature are indeed those orienting behavior. This insight is as relevant for studies in the sociology of medicine as it is for studies of medical care such as those conducted by Wennberg (1999) and those he has inspired. It suggests that the key to understanding practice variation is in comparing organizations of similar prestige.

The difference across organizations in the use of one form of knowledge, that originating in Medline and other computer-mediated resources, is a good example of how the organization moderates factors we think of as characteristic of the profession as a whole. Specifically, imbalance in the amount Medline is used offers some evidence that a “knowledge elite” exists among academic medical centers. Our results, however, somewhat differ from those expected by Eliot Freidson (1984). Freidson predicted that profession-wide standards for medical knowledge would be set by those whose authority derives from their administrative capacities. He argued that those governing professional associations such as the American College of Physicians or the American Medical Association would set the standard to which all practitioners should strive. The existence of a “knowledge elite” in medicine is signaled by the positive relationship between hospital prestige and the average rate of Medline use across settings (see Table 2). Top-ranked hospitals present themselves as developing and applying scientific research in order to be legitimized as institutions that are serious about the principles valued in a profession currently concerned with its scientific underpinnings.8 The importance of these rankings to peer institutions means that the leading hospitals will likely establish standards for information collection that will be emulated by lower-ranked rivals. Yet our analysis also implies that those lower-ranked hospitals will not easily adjust; despite the valuation of journal readership, the higher value placed on clinical work in those settings means that innovations may diffuse more slowly there between colleagues. Nonetheless, in terms of the time available to access and process scientific findings, the differences between the knowledge elites and those in other hospitals may grow over time, but their mutual dependence also means the distance might be marginal.

Table 2.

Differences Across Hospitals in Physicians’ Information Use, Demographic Characteristics, and Work Activities

| Variable | All hospitals | Higherprestige hospitals | Lower-prestige hospitals | p -value of hospital comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

||

| Number of times used Medline/month | 11.31 (11.23) |

13.03 (12.09) |

8.00 (8.18) |

0.045* |

| Number of journals read/month | 4.01 (2.68) |

3.97 (2.68) |

4.06 (2.49) |

0.108 |

| Percent of time doing clinical work | 65.83 (22.16) |

63.49 (21.48) |

68.77 (21.68) |

0.369 |

| Age | 42.52 (9.11) |

40.70 (9.10) |

44.49 (8.98) |

0.005** |

| Experience in hospital | 7.50 (6.66) |

5.75 (5.24) |

9.64 (7.57) |

0.016* |

| Prestige of medical school | 3.48 (0.72) |

3.73 (0.78) |

3.28 (0.64) |

0.008** |

| Subspecialist | 0.41 (0.50) |

0.39 (0.49) |

0.45 (0.50) |

0.088 |

| Male (=1) | 0.56 (0.49) |

0.55 (0.50) |

0.58 (0.50) |

0.212 |

| Observations | 126 | 74 | 52 |

p <.05;

p <.01 (two-tailed tests).

Our conclusions about the relationship between organization prestige and physician esteem are qualified by several limitations of the data. First, the wording of our social network measure limits the potential set of nominations. Because we ask physicians to name others to which they usually turn for advice, it is possible that certain physicians who would otherwise be designated as having high esteem are difficult to reach by colleagues for face-to-face or mediated consultation. We may also be undersampling weaker ties since the survey allows for only three nominations. Although this approach allows our results to be commensurable with studies that have previously used these questions (e.g., Coleman et al. 1966, Burt 1987), future work might draw from data that reveal instances of advice-giving such as through the use of email transcripts. Second, we know little about how different information regimes are employed in the contexts of everyday work. Since our data neither tells us the different explicit applications of cross-journal reading and Medline use, nor about the types of doctors who predominantly engage in one information regime or another, we can only infer how this knowledge relates to dominant tasks. Finally, we need to know more about physicians’ interpretations of the medical literature. Our data neither indicates how physicians interpret the knowledge they access, nor does it measure whether physicians reject findings, incorporate them into their work, or share them with colleagues. As Simmel (1965) put it, “cognitive representations of things are not poured into us like nuts in a sack” (290). Since we do not know what gets filtered in the initial retrieval or in conversations, we are limited in our ability to make concrete conclusions about diffusion, and of praxis – the ultimate goal of the evidence-based medicine movement. For this reason future sociological work on knowledge might capture this interaction with the literature.

With these results in mind, and returning to the puzzle presented at the beginning of the paper, we have seen that the idea that clinical and scientific communities necessarily come into conflict is misleading. Instead, the factors that bind colleagues in these organizational contexts appear to vary in ways that are complementary across organizations and may also offer insight into more macro-level changes in medical knowledge. Whereas the broad knowledge of evidence-based medicine is valued more in low-prestige hospitals than high-prestige ones, the focus in the high-prestige hospitals may be on innovation, the creation of new evidence and practices for others to follow. Individually, then, physicians in each knowledge strata can be concerned with attaining and maintaining esteem from colleagues, while collectively advancing their field as a whole. By so doing they can maintain professional autonomy from outside influences such as insurance providers, the medical industry, patients, and the state – stakeholders themselves seeking to structure the knowledge used in medical care.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the helpful suggestions of Andrew Abbott, Larry Casalino, Edward Laumann, Karen Lutfey, Andrew Papachristos, Bernice Pescosolido, Maria Porter, and the audience at the 2006 ASA and 2008 Academy Health annual meetings. Special thanks should also be given to site representatives of the Multicenter Trial of Academic Hospitalists for collecting the data used in this study, and especially to Tosha Wetterneck for her detailed comments. Data collection for this project was supported by Agency for Health Care Quality and Research (AHRQ) grant R01-HS10597. Dr. Meltzer would like to acknowledge financial support for this work by AHRQ through the Hospital Medicine and Economics Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics (CERT) U18 HS016967-01 (Meltzer, PI), the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator Program (Grant # 63910, Meltzer, PI), and a National Institute of Aging Midcareer Career Development Award K24-AG31326 (Meltzer, PI). Daniel Menchik would like to acknowledge support from the Oxford Institute of Ageing and the University of Chicago Center on the Demography and Economics of Aging.

Footnotes

Ioannidis (2005) shows that one-third of the most-cited studies on new drugs and treatments reported between 1990 and 2003 in the top three medical journals (New England Journal of Medicine, The Journal of the American Medical Association, and The Lancet) were eventually contradicted or corrected to report weaker findings.

Davidoff et al. (1995) estimate that physicians in general medicine would need to examine 19 articles a day, 365 days a year, to keep abreast of all medical advances reported in “primary” journals.

Percentages lower than this resulted in the inclusion of many physicians who were predominantly researchers or administrators. Percentages higher than this resulted in a very large reduction in power. As will be shown, the resultant average percentage of those doing clinical work differs by only two percent across settings, suggesting this cutoff did not have the uneven effects across contexts that might be expected when comparing organizations with differing levels of prestige.

A high score is three standard deviations away from the mean level of quality in a subspecialty.

The use of medical school rankings to denote the prestige of associated hospitals is further validated by their alignment with hospital rankings; the top 17 hospitals – including the three we label high-prestige – are consistently affiliated with the top medical schools.

To consider the proposition that small changes in amount of experience may influence esteem acquisition disproportionately, we tried logarithmic and exponential transformations for the experience and age variables. We found that these transformations did not change the sign or precision of these estimates or others in the regression.

This coefficient is a result of the same regression shown but in this case we controlled for the number of physicians in each hospital. This is necessary for talking about the number of colleagues instead of the proportion of physicians who nominated an individual relative to the hospital population.

Johns Hopkins Medicine has provided international leadership in the education of physicians and medical scientists, in biomedical research, and in the application of medical knowledge to sustain health care… Hopkins Medicine brings together the faculty physicians and scientists of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine with organizations, community physicians, nurses and other professionals… (http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org, accessed July 1, 2008).

In striking contrast, the front page of the lowest-prestige hospital in our study displays a picture of a nurse.

Contributor Information

Daniel A. Menchik, Department of Sociology, The University of Chicago

David O. Meltzer, Pritzker School of Medicine, The University of Chicago

References

- Abbott Andrew. Status and Status Strain in the Professions. American Journal of Sociology. 1981;86:819–835. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott Andrew. The System of Professions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Anspach Renée R. Deciding Who Lives: Fateful Choices in the Intensive Care Nursery. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong David. Clinical Autonomy, Individual and Collective: The Problem of Changing Doctors’ Behavior. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55:1771–1777. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary, Murphy Kevin, Werning Ivan. The Equilibrium Distribution of Income and the Market for Status. The Journal of Political Economy. 2005;113:282–310. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Howard, Geer Blanche, Hughes C Everett, Strauss Anselm. Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Nancy, Casebeer Linda, Kristofco Robert, Strasser Sheryl. Physicians’ Internet Information-Seeking Behaviors. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2004;24:31–38. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340240106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Joseph, Fişek M Hamit. Diffuse Status Characteristics and the Spread of Status Value: A Formal Theory. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;111:1038–79. [Google Scholar]

- Berkwits Michael. From Practice to Research: The Case For Criticism in an Age of Evidence. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:1539–1545. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau Peter. The Dynamics of Bureaucracy: A Study of Interpersonal Relations in Two Government Agencies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Blau Peter, Duncan Otis D. The American Occupational Structure. New York: John Wiley; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bosk Charles. Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bosk Charles. Occupational Rituals in Patient Management. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;303:71–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007103030203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Medical Journal. Editorial. British Medical Journal. 2005;38:7473. [Google Scholar]

- Burt Ronald S. Social Contagion and Diffusion: Cohesion versus Structural Equivalence. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92:1287–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis Nicholas. Social Networks and Collateral Health Effects. British Medical Journal. 2000;329:184–185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7459.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clogg Clifford, Petkova Eva, Haritou Adamantios. Statistical Methods for Comparing Regression Coefficients between Models. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100:1261–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cole Jonathan R, Lipton James. The Reputations of American Medical Schools. Social Forces. 1977;55:662–684. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James S. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James S, Katz Elihu, Menzel Herbert. Medical Innovation: A Diffusion Study. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Co; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Costenbader Elizabeth, Valente Thomas. The stability of centrality measures when networks are sampled. Social Networks. 2003;25:283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Croog Sydney, Steeg Donna Ver. The Hospital as a Social System. In: Freeman H, Levine S, Reeder L, editors. Handbook of Medical Sociology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1972. pp. 274–314. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff Frank, Haynes Brian, Sackett David, Smith Richard. Evidence Based Medicine: A New Journal to Help Doctors Identify the Information They Need. British Medical Journal. 1995;310:1085–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6987.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Renee C. Experiment Perilous: Doctors and Patients Facing the Unknown. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman Linton. Centrality in Social Networks: Conceptual Clarification. Social Networks. 1979;1:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson Eliot. Client Control and Medical Practice. American Journal of Sociology. 1960;65:374–82. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson Eliot. The Profession of Medicine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson Eliot. The Changing Nature of Professional Control. Annual Review of Sociology. 1984;10:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhamer Herbert, Shils Edward. Types of Power and Status. American Journal of Sociology. 1939;45:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Goode William J. The Celebration of Heroes. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gould Roger. The Origins of Status Hierarchies: A Formal Theory and Empirical Test. American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107:1143–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hafferty Fredric, Light Donald. Professional Dynamics and the Changing Nature of Medical Work. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:132–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardey Michael. Doctor in the House: The Internet as a Source of Lay Health Knowledge and the Challenge to Expertise. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1999;21:820–835. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz John, Laumann Edward O. Chicago Lawyers: The Social Structure of the Bar. Chicago: Russell Sage Foundation; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz John, Nelson Robert, Sandefur Rebecca, Laumann Edward O. Urban Lawyers: The New Social Structure of the Bar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff Tim. The Social Organization of Physician-Managers in a Changing HMO. Work and Occupations. 1999;26:324–351. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter Kathryn. Doctors’ Stories: The Narrative Structure of Medical Knowledge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams Andrew, Shapiro David, Brennan Troyen A. Medical Practice Guidelines in Malpractice Litigation: An Early Retrospective. Journal of Health, Politics, Policy and Law. 1996;21:289–313. doi: 10.1215/03616878-21-2-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Exploring the Map of Clinical Research for the Coming Decade. Washington D.C.: Board on Health Sciences Policy; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis John P. Contradicted and Initially Stronger Effects in Highly Cited Clinical Research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:218–228. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Lei. PhD dissertation. Department of Sociology, The University of Chicago; Chicago, IL: 2005. Stratification in the medical profession. [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzny Arnold, Shortell Steven. Creating and Managing the Future. In: Shortell, Kaluzny, editors. Health Care Management: Organization Design and behavior. New York: Thompson; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Harris H, Laumann Edward O. Network endorsement and social stratification in the legal profession. In: Buskens V, Raub W, Snijders C, editors. Research in the Sociology of Organizations. Amsterdam: JAI; 2003. pp. 243–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerlov Per, Veninga Catharina CM, Muskova Maria, Hummers-Pradier Eva, Stalsby Lundborg C, Andrew Marit, Haaijer-Ruskamp Flora. Asthma Management in Five European Countries: Doctors’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Prescribing Behaviour. European Respiratory Journal. 2000;15:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leicht Kevin, Fennell Mary. Professional Work: A Sociological Approach. Oxford: Blackwell; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martin John Levi. Is Power Sexy? American Journal of Sociology. 2005;111:408–446. [Google Scholar]

- Mather Lynn M, McEwen Craig A, Maiman Richard. Divorce lawyers at work. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Menchik Daniel, Jin Lei. When Do Physicians Follow Their Patients’ Orders?. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association; Montreal, Canada. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Merton Robert. Some Preliminaries to a Sociology of Medical Education. In: Merton Robert, Reader George, Kendall Patricia., editors. The Student-Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1957. pp. 2–77. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Steven. Prescription for Leadership: Training for the Medical Elite. Chicago: Aldine; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Moldoveanu Mihnea C, Baum Joel AC, Rowley Tim J. Information Strategies, Information Regimes, and the Evolution of Interfirm Network Topologies. In: Dansereau F, Yammarino FJ, editors. Research on Multilevel Issues. Vol. 2. Oxford UK: JAI/Elsevier; 2002. pp. 221–264. [Google Scholar]

- Mykhalovskiy Eric, Weir Lorna. The Problem of Evidence-based Medicine: Directions for Social Science. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59:1059–69. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu Uchenna C, Cox Becky. The Impact of the Internet on Doctor-patient Relationships. Journal of Medical Informatics. 2000;6:156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons Talcott. The Social System. New York: The Free Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons Talcott. On the Concept of Influence. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1963;27:37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Perrow Charles. A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Organizations. American Sociological Review. 1967;32:194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice. Beyond Rational Choice: The Social Dynamics of How People Seek Help. The American Journal of Sociology. 1992;97:1096–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Podolny Joel. Networks as the Pipes and Prisms of the Market. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;107:33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pope Catherine. Resisting Evidence: The Study of Evidence-Based Medicine as a Contemporary Social Movement. Health. 2003;7:267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Powell John, Clarke Aileen. The WWW of the World Wide Web: Who, What, and Why? Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2002;4:e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4.1.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway Cecilia L. The Social Construction of Status Value: Gender and other Nominal Characteristics. Social Forces. 1991;70:367–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway Cecilia L, Erickson Kristan G. Creating and Spreading Status Beliefs. American Journal of Sociology. 2000;106:579–615. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau Jean Jacques. Discourse on the Origin and the Foundations of Inequality Among Men. In: Gourevich V, editor. The Discourses and Other Early Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; [1755] 2006. pp. 113–222. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett David, Rosenberg W. The Need for Evidence-based Medicine. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1995;88:620–624. doi: 10.1177/014107689508801105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur Rebecca. Work and Honor in the Law: Prestige and the Division of Lawyers’ Labor. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:382–403. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Richard. PhD dissertation. Department of Sociology, The University of Chicago; Chicago, IL: 1961. Professional Workers in a Bureaucratic Setting. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Richard, Ruef Martin, Mendel Peter, Caronna Carol. Institutional Change and Healthcare Organizations: From Professional Dominance to Managed Care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shils Edward. Deference. In: Grusky DB, editor. Social Stratification: Class, Race and Gender in Sociological Perspective. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; [1968] 1994. pp. 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Shortell Steven. Occupational Prestige Differences Within the Medical and Allied Health Professionals. Social Science and Medicine. 1974;8:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(74)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmel Georg. Essays on Sociology, Philosophy, and Aesthetics. New York: Harper Torchbooks; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Smeele Ivo J, Grol Richard, van Schayck Constant, van den Bosch Robert, van den Hoogen Henk, Muris Jean. Can Small Group Education and Peer Review Improve Care for Patients with Asthma Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease? Quality in Health Care. 1999;8:92–98. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.2.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Stelling Joan, Bucher Rue. Autonomy and Monitoring on Hospital Wards. Sociological Quarterly. 1972;13:431–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stovel Katherine, Fountain Christine. Center for Statistics in the Social Sciences Working Paper #30. University of Washington; 2006. Hearing about a Job: A Simulation Model of Differential Information Flow and Job Matching. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss Sharon, McAlister Finlay. Applying the Results of Trials and Systematic Reviews to our Individual Patients. Evidence Based Mental Health. 2001;4:6–7. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.4.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans Stefan, Angell Allison. Evidence-Based Medicine, Clinical Uncertainty, and Learning to Doctor. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:342–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. News and World Report. The Top Hospitals and Medical Schools. 2007 Retrieved August 25, 2007 ( http://health.usnews.com/usnews/health/best-hospitals/honorroll.htm)

- Wennberg John M. Understanding Geographic Variations in Health Care Delivery. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;332:52–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemljica Barbara, Hlebecb Valentina. Reliability of measures of centrality and prominence. Social Networks. 2005;27:73–88. [Google Scholar]