Abstract

Objective This study aims to assess head volume (HV) alterations at 11 to 14 weeks in fetuses with congenital heart defects (CHD).

Methods A retrospective case–control study on 100 normal and 26 CHD fetuses was conducted. The fetuses had a first trimester scan with volume data sets stored from which HV was calculated. The mean HV and HV as a function of crown–rump length (CRL) in normal fetuses were compared with established normograms. Mean HV, HV as a function of CRL, and HV/CRL were compared between normal and CHD fetuses. Nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test was used with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results Overall, 83 normal and 19 CHD fetuses were included. The mean HV and HV as a function of CRL in the normal fetuses were comparable to what has been established (p = 0.451 and 0.801, respectively). The mean HV was statistically smaller in fetuses with CHD, particularly those with hypoplastic left heart (HLH): 10.7 mL in HLH versus 13.0 mL in normal fetuses (p = 0.043). The HV/CRL was statistically smaller in fetuses with CHD (p = 0.01).

Conclusion Despite the small sample size, our case series suggests that alterations in HV may potentially be apparent as early as 11 to 14 weeks in CHD fetuses, particularly those with HLH. Larger prospective studies are needed to validate our findings.

Keywords: heart defects, first trimester, head volume alterations, 3D volumetry

Fetuses with congenital heart defects (CHD) may demonstrate adaptive changes in brain perfusion that result in brain growth modifications.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Donofrio et al described the brain-sparing effect in fetuses with CHD in 20031 where an autoregulatory circulatory adaptation occurs. The brain-sparing effect leads to enhanced brain perfusion as exemplified by changes in the cerebral to placental resistance ratio (CPR).1 The extent of the brain-sparing effect correlates with the underlying cardiac defect and is most notable in fetuses with a physiological single ventricle.1

Several studies have addressed and demonstrated progressive in utero alterations in fetal head development in fetuses with CHD as early as the second trimester extending into infancy.2 3 4 5 6 7 8 In addition, the head volume (HV) seems to have a predictive value when it comes to assessing the extent of neurological deficits present in affected fetuses well into adolescence.5 6 8 9 10 11 This has led to an increasing focus on the study of fetal brain volumetry3 4 7 8 12 13 and Doppler indexes, namely, the CPR (calculated as the ratio of the pulsatility index of the middle cerebral artery to that of the umbilical artery).1 2 4 7 8 The ultimate aim is to unravel the underlying mechanism and determine the timing of brain injury. Once this goal is accomplished, it may then become a possibility to tailor in utero interventions to minimize neurodevelopmental impairment in this at-risk population.1 4 11 12

Today, and with the ever increasing global implementation of first trimester screening, we have access to ≈70% of fetuses whose mothers present for nuchal translucency (NT) assessment,14 and the first trimester scan is no longer limited to screening for aneuploidy. Enabled by advancing sonographic technology, it has solidly evolved into the full anatomical survey at 11 to 14 weeks,15 16 inclusive of screening for cardiac defects.16 17 18 19 20 In addition, there has been significant evidence as to the importance of various sonographic markers such as the fetal NT,17 18 tricuspid regurgitation,21 ductus venosus flow,22 23 and cardiac axis24 for the early identification of fetuses at risk for CHD, providing further support to the importance of safeguarding the first trimester scan in the era of noninvasive prenatal testing.

As such, the aim of our study was to assess the presence of HV alterations in fetuses with CHD at 11 to 14 weeks.

Methods

This was a single-center retrospective case–control study, approved by our review board, on 100 normal fetuses and 26 fetuses with CHD presenting for routine first trimester screening at 11 to 14 weeks. The 100 normal fetuses were selected by creating a “query” using the Astraia software GmbH (München, Germany) on fetuses who were confirmed to be term-healthy live births at > 37 weeks of gestation, and who had undergone both a first and a second trimester scan at our center. The most recent 100 fetuses fulfilling the above criteria, at the time of data acquisition, were included in the analysis. Maternal body mass index was obtained. All fetuses had a transabdominal first trimester scan with the fetal crown–rump length (CRL), biparietal diameter (BPD), and NT measured among various parameters, and a comprehensive anatomical assessment performed with images stored. Volume data sets of the entire fetus were acquired and stored on all. The scans and volume analyses were performed by a single sonologist certified by the Fetal Medicine Foundation using 4 to 8 MHz convex high-resolution probes with two-dimensional and three-dimensional (3D) capabilities (GE Voluson 730 Expert and E8 ultrasound systems, Kretz, Zipf, Austria). From the stored images, the cardiac axis was measured retrospectively at the level of the four-chamber view. To calculate the HV, the plane of the BPD was reconstructed from the stored 3D volume data sets using rotation along the three axes. Virtual organ computer-aided analysis was subsequently activated, using manual trace at a rotational angle of 30 degrees along the Y axis, for HV calculation (Fig. 1). Fetuses with suboptimal volumes due to motion artifact and shadowing were excluded from the analysis. All controls had a normal second trimester scan by the same sonologist and a normal neonatal examination at birth. The fetuses with CHD were evaluated by a pediatric cardiologist, and the diagnosis was confirmed. In those fetuses with CHD, the presence of extracardiac anomalies was recorded, and the results of karyotype were obtained, when applicable. Live born fetuses with CHD were reevaluated by the same pediatric cardiologist at birth. Data were calculated and expressed in means and standard deviations of means. The mean HV, and HV as a function of the CRL in the normal fetuses were compared with what has been established by Falcon et al.25 The HV as a function of the CRL in fetuses with CHD (grouped as hypoplastic left heart [HLH] and other) was plotted against the normal fetuses. In addition, the HV/CRL was compared between normal fetuses and those with CHD (grouped as HLH and other). Nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for comparing the measurements. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

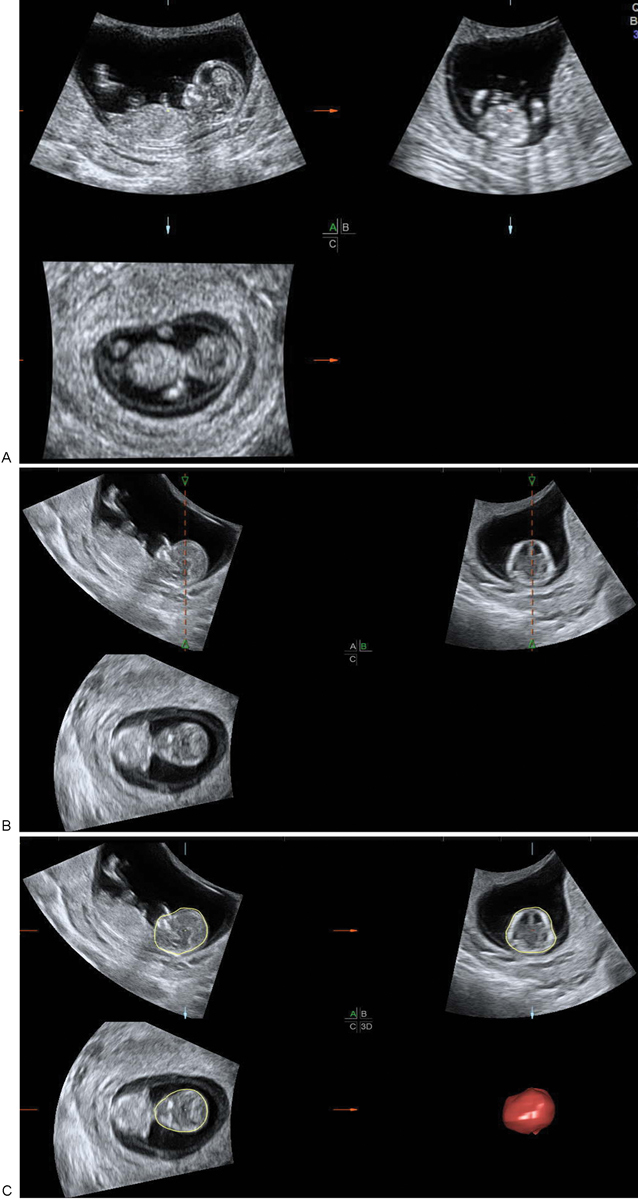

Fig. 1.

(A) Three-dimensional volume of a normal first trimester fetus at 12 weeks 4 days displayed in the three orthogonal planes. (B) The reference dot is moved to the fetal head and rotation is performed along the three axes to optimize the plane of the fetal biparietal diameter in plane B. Virtual organ computer-aided analysis is activated using plane B as the reference plane with a rotational angle of 30 degrees along the Y axis. (C) Upon completion of six manual traces at 30 degrees along the Y axis, the volume of the fetal head is automatically generated.

Results

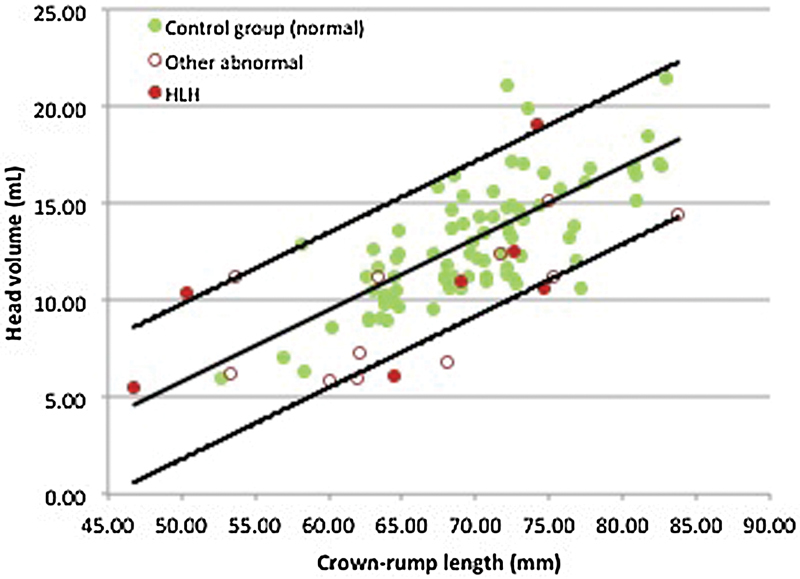

A total of 102 fetuses were included in the analysis: 83/100 (83%) of the normal fetuses and 19/26 (73%) of those with CHD. The remaining 17 normal fetuses and 7 fetuses with CHD were excluded from the analysis due to suboptimal volumes. Population demographics and results are presented in Table 1. The patient characteristics were similar in both the normal fetuses and those with CHD with a mean maternal body mass index of 25.1 versus 24.8 kg/m2 (p = 0.945); CRL of 69.4 versus 68.8 mm (p = 0.756); BPD 22.8 versus 20.6 mm (p = 0.061); and cardiac axis of 46.6 versus 59.1 degrees (p = 0.220), respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the NT between the normal fetuses and those with CHD with a mean of 1.7 versus 4.1 mm (p < 0.0001). The mean HV in normal fetuses was comparable to what has already been established by Falcon et al25 (p = 0.451). However, the HV was statistically smaller in fetuses with CHD, particularly those with HLH, with a mean HV of 10.7 mL in HLH versus 13.0 mL in the normal fetuses (p = 0.043), and the HV/CRL was statistically smaller in fetuses with CHD when compared with normal fetuses (p = 0.01) (Table 1). The normogram for the HV as a function of the CRL in the normal fetuses in this study was comparable to what has previously been established by Falcon et al25 (p = 0.801). Nonetheless, the HV as a function of the CRL revealed a significant difference between CHD fetuses and normal fetuses with a statistically smaller HV in fetuses with CHD. This was particularly applicable to fetuses with HLH (Fig. 2).

Table 1. Population characteristics.

| Characteristics | Control group (n = 83) | CHD group (n = 19) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLH (n = 7) | Other (n = 12) | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.1 ± 4.3 | 24.0 ± 2.6 | 25.2 ± 4.7 | 0.945 |

| Crown–rump length (mm) | 69.4 ± 6.6 | 65.0 ± 10.7 | 69.3 ± 9.2 | 0.756 |

| Biparietal diameter (mm) | 22.8 ± 2.0 | 20.6 ± 3.2 | 21.3 ± 3.2 | 0.061 |

| Nuchal translucency (mm) | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 1.7 | 4.5 ± 3.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiac axis (degrees) | 46.6 ± 10.0 | 59.1 ± 20.9 | 49.3 ± 25.6 | 0.220 |

| Head volume (mL) | 13.0 ± 3.1 | 10.7 ± 4.5 | 10.2 ± 3.7 | 0.043 |

| Head volume/crown–rump length | 18.4 ± 3.4 | 16.5 ± 5.4 | 15.1 ± 4.3 | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: CHD, congenital heart defects; HLH, hypoplastic left heart.

Note: Data are mean ± standard deviation (range). The p values were calculated using the nonparametric approach comparing all three columns.

Fig. 2.

Normogram of the fetal head volume as a function of the fetal crown–rump length for 83 normal fetuses (green circles) and 19 fetuses with congenital heart defects represented as those with a hypoplastic left heart (red circles) versus other (red open circles).

Even though there tended to be complex cardiac defects in certain cases, we grouped the CHD fetuses into five categories based on what was confirmed in the first and early second trimesters. This was secondary to having some fetuses undergo termination or suffer in utero demise before their second trimester scan. This was further affected by the fact that none of the families consented to a pathological examination as a result of cultural and religious beliefs. As a consequence, there were 7/19 (36.8%) fetuses in the HLH category; 6/19 (31.2%) fetuses in the ventricular septal defect/atrioventricular canal category; 3/19 (15.8%) fetuses in the hypoplastic right heart category; 2/19 (10.5%) fetuses in the heterotaxy/situs inversus category, and 1/19 (5.3%) fetuses in the tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) category. Karyotype was only available on 4/19 (21%) fetuses: 2 were euploid and 2 had trisomy 21. There were 5/19 (26.3%) fetuses with isolated CHD, another 5/19 (26.3%) fetuses with hydrops fetalis, and 9/19 (47.4%) fetuses with aneuploidy (n = 2) and other structural defects (n = 7). The structural defects included a case each of a neural tube defect, bladder outlet obstruction/sacral agenesis, left atrial isomerism, situs inversus, single umbilical artery, holoprosencephaly/proboscis, and omphalocele. Of the 19 fetuses, 2 were live born (10.5%). Termination of pregnancy was performed on 13/19 (68.4%). There was spontaneous in utero demise in 2/19 (10.5%). In addition, 2/19 (10.5%) were lost to follow-up. A complete summary of the 19 cases is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Detailed summary of the individual 19 cases of fetuses with congenital heart defects in ascending order according to head volume.

| Case | Congenital heart defect | Extracardiac findings | HV (mL) | CRL (mm) | HV/CRL | NT (mm) | BPD (mm) | CAx (degrees) | NB | TR | DVa (a/PI) | Karyotype | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C19 | Hypoplastic left heart | Neural tube defect | 5.51 | 46.80 | 11.77 | 3.00 | 17.40 | 64.36 | Not examined | TR | Not examined | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C17 | Tetralogy of Fallot | Hydrops fetalis | 5.83 | 60.00 | 9.72 | 11.70 | 17.40 | 51.49 | Absent | Normal | Not examined | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C11 | Atrioventricular canal | Hydrops fetalis | 5.94 | 61.90 | 9.60 | 10.00 | 19.70 | 30.99 | Not examined | Normal | PI = 1.8 | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| C6 | Hypoplastic left heart | Hydrops fetalis | 6.13 | 64.40 | 9.52 | 7.90 | 21.70 | 35.95 | Present | TR | Reversed-a wave | Unknown | Fetal demise in utero |

| C8 | Hypoplastic right heart | Omphalocele | 6.25 | 53.40 | 11.70 | 5.60 | 18.00 | 26.81 | Present | Normal | Not examined | Euploid | Termination of pregnancy |

| C18 | Atrioventricular canal | Hydrops fetalis | 6.79 | 68.00 | 9.99 | 9.40 | 20.10 | 38.18 | Absent | Not examined | PI = 3.1 | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| C7 | Ventricular septal defect | Holoprosencephaly/proboscis | 7.32 | 62.10 | 11.79 | 3.60 | 18.20 | 124.62 | Absent | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C10 | Hypoplastic left heart | None | 10.37 | 50.30 | 20.62 | 4.00 | 15.60 | 56.51 | Absent | Normal | PI = 1.4 | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C9 | Hypoplastic left heart | None | 10.60 | 74.60 | 14.21 | 3.70 | 23.80 | 40.3 | Present | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C12 | Hypoplastic left heart | Trisomy 21 | 11.02 | 69.00 | 15.97 | 4.80 | 19.70 | 13.15 | Present | TR | Not examined | Trisomy 21 | Termination of pregnancy |

| C1 | Ventricular septal defect | Trisomy 21 | 11.23 | 63.30 | 17.74 | 3.40 | 22.90 | 68.9 | Absent | Normal | Not examined | Trisomy 21 | Termination of pregnancy |

| C2 | Hypoplastic right heart | None | 11.23 | 75.20 | 14.93 | 2.20 | 23.30 | 41.84 | Present | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C4 | Atrioventricular canal | Hydrops fetalis | 11.24 | 53.70 | 20.93 | 3.25 | 20.20 | 84.98 | Present | Normal | Reversed-a wave | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C13 | Atrioventricular canal | None | 12.35 | 71.70 | 17.22 | 1.80 | 22.70 | 42.71 | Present | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Live birth |

| C3 | Hypoplastic left heart | None | 12.55 | 72.60 | 17.29 | 4.20 | 22.70 | 47.45 | Present | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

| C16 | Hypoplastic right heart | Single umbilical artery | 14.44 | 83.80 | 17.23 | 10.60 | 23.20 | 78.05 | Present | Normal | PI = 3 | Unknown | Fetal demise in utero |

| C15 | Dexterocardia | Situs inversus | 15.09 | 75.00 | 20.12 | 2.40 | 25.90 | 37.92 | Present | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Live birth |

| C5 | Heterotaxy | Left isomerism | 15.22 | 77.70 | 19.59 | 3.80 | 24.30 | 85.6 | Present | Normal | Reversed-a wave | Euploid | Termination of pregnancy |

| C14 | Hypoplastic left heart | Megacystis/sacral agenesis | 19.10 | 74.20 | 25.74 | 3.10 | 23.50 | 64.36 | Present | TR | Not examined | Unknown | Termination of pregnancy |

Abbreviations: BPD, biparietal diameter; CAx, cardiac axis; CRL, crown–rump length; DV, ductus venosus; HV, head volume; NB, nasal bone; NT, nuchal translucency; PI, pulsatility index; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

For the earlier part of the study, we were utilizing the a-wave in the evaluation of the DV flow, however, in the latter cases we were measuring the pulsatility index.

Discussion

There has been growing evidence in support of alterations in head size and brain development in fetuses with CHD commencing as early as the second trimester.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 One of the most recent reports by Schellen et al addresses the role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 20 to 34 weeks in the detection of brain alterations in fetuses with TOF, where they noted altered brain growth at ≤ 25 weeks with decreased volumes of gray and white matter, and increased cerebrospinal fluid spaces.7 Masoller et al reported their impressive data utilizing MRI, where they showed that fetuses with CHD had total brain volumes < 10th centile. In addition, Doppler indexes and cephalic biometry, at 19 to 24 weeks, served as independent predictors for abnormal brain development at birth.8 Most recently, Rychik et al noted progressive alterations in the BPD and head circumference of fetuses with HLH where before 28 weeks, the fetal BPD was low but the head circumference was normal. However, beyond 28 weeks, both BPD and HC diminished significantly.13 Of note is that all of the above studies were performed on fetuses with isolated CHD.

To our knowledge, our study provides the earliest evidence in support of potential HV alterations at 11 to 14 weeks in fetuses with CHD. Keeping in mind that only 26% of our fetuses had isolated CHD, our findings are contrary to what has been established in the second trimester and indicate that the fetal BPD is not significantly changed in the first trimester in the presence of CHD when compared with normal fetuses. This is in contrast to what has been reported by Masoller et al in a cohort of fetuses with various types of CHD,8 and Rychik et al who reported on fetuses with HLH.13 As such, the diminishing BPD noted in the second trimester may be a progressive change with advancing gestation and a potential sign of neurological impairment. This remains to be seen with future well-designed prospective studies that may serially follow fetuses with CHD from as early as when the diagnosis is made in the first trimester up until birth.

According to our data, there was a statistically significant difference in first trimester HV when comparing our CHD fetuses, particularly those with HLH, to their normal counterparts. This may indicate underlying brain volumetric changes that lead to a global decrease in HV without impacting the fetal BPD. Of note is that while Schellen et al described decreased volumes of gray and white matter in fetuses with TOF, commencing in the second trimester, there was concomitant increase in cerebrospinal fluid spaces,7 indicating complex changes in the developing fetal brain that cannot be easily assessed in the first trimester, and should be the focus of future research. This may be further complicated by variations in the response of the anterior and posterior cerebral circulation to hypoxia in cases with CHD,7 and preferential underlying genetic abnormalities that have the potential of negatively impacting the developing brain, and increasing its vulnerability to prenatal injury.1

There are several limitations to our study: first and foremost it is retrospective in nature with only 19 cases of CHD. Second, not all 19 fetuses with CHD were isolated cardiac findings. Only 5/19 (26.3%) of our fetuses had isolated CHD. Another 5/19 (26.3%) fetuses had hydrops fetalis, indicating cardiovascular decompensation. Of the remaining 9/19 (47.4%): 7 fetuses had other structural abnormalities, and 2 had trisomy 21. The presence of other structural abnormalities and underlying aneuploidies may have affected head volume. This is particularly applicable to the fetus with a neural tube defect, and the 2 fetuses with trisomy 21 given Falcon et al had shown a significantly smaller head volume in trisomy 21, trisomy 13, and Turner syndrome fetuses.25 Though there may have been missed diagnoses at this point in gestation, we have previously reported on a 70% first trimester detection rate for major structural abnormalities in the first trimester.15 Third, most CHD fetuses in this study were terminated, or suffered in utero demise, precluding a second trimester scan, and there were no postmortem examinations performed due to cultural and religious preferences. This resulted in grouping the CHD fetuses into five major cardiac subtypes. This study-limitation, resulting from early fetal loss and the absence of a postmortem examination, will likely affect similar future first trimester studies. As such, obtaining four-dimensional volumes of affected fetal hearts using spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) modality may help in offline evaluation and confirmation.26 In addition, this limitation may potentially be curtailed in centers of excellence through the postmortem utilization of high-field MR at 9.5 T,27 or microcomputed tomography,28 both of which have been shown to allow for detailed postmortem fetal cardiac assessment at 11–14 weeks. Fourth, we calculated HV and not brain volume and did not account for the cerebrospinal fluid spaces. Finally, and due to gestational age limitations, the Doppler indexes of the middle cerebral and umbilical arteries were not routinely obtained in this study and hence, the CPR was not available for analysis and correlation with the data.

The strength of our study is the fact that all scans were performed by a single sonologist at a single center with thorough documentation, and where outcome was available on the majority of the affected fetuses. In addition, there was confirmation by pediatric cardiology prenatally and postnatally, whenever possible. Though there was no intrarater variability assessment for the sonologist performing the scans, plotting the fetal HV against the CRL for the normal fetuses resulted in a similar normogram and a comparable mean HV to what has already been established by Falcon et al25 (p = 0.801 and 0.451, respectively), supporting the reliability of our methods and techniques. Our study also supports the important role of 3D ultrasound, in fetal brain assessment and volumetry, as a feasible, reliable, safe, and inexpensive modality that can be utilized as early as the first trimester.

Despite the various limitations and the small sample size, our case series suggests that HV alterations may potentially be present in fetuses with CHD as early as 11 to 14 weeks. Diagnosis precedes intervention; the earlier it may be secured, the higher the likelihood of understanding the underlying causative mechanisms, and the better the chance for early intervention to optimize the outcome of the affected fetuses. This may ultimately lead to earlier surgical29 30 31 32 and nonsurgical interventions8 12 33 34 35 to protect the neurodevelopment of fetuses with CHD. As such, our data highlight the need for larger prospective studies, on fetuses with isolated CHD, with the incorporation of Doppler parameters, to validate our findings.

As Donofrio and Massaro so elegantly stated in 2010: “In the future, fetal management and intervention strategies for specific defects may ultimately play a role to improve in utero hemodynamics and increase cerebral oxygen delivery to enhance brain growth and improve early neurodevelopment.”36

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to express their sincerest appreciation to Prof. Daniela Prayer for her encouragement, guidance, and critique.

Disclosures The authors have no disclosures.

Note

This work was presented orally at the AIUM Annual Convention; March 17–21, 2016; New York, NY.

References

- 1.Donofrio M T, Bremer Y A, Schieken R M. et al. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in fetuses with congenital heart disease: the brain sparing effect. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24(5):436–443. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-0404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg C, Gembruch O, Gembruch U, Geipel A. Doppler indices of the middle cerebral artery in fetuses with cardiac defects theoretically associated with impaired cerebral oxygen delivery in utero: is there a brain-sparing effect? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(6):666–672. doi: 10.1002/uog.7474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limperopoulos C, Tworetzky W, McElhinney D B. et al. Brain volume and metabolism in fetuses with congenital heart disease: evaluation with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Circulation. 2010;121(1):26–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masoller N, Martínez J M, Gómez O. et al. Evidence of second-trimester changes in head biometry and brain perfusion in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44(2):182–187. doi: 10.1002/uog.13373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khalil A, Suff N, Thilaganathan B, Hurrell A, Cooper D, Carvalho J S. Brain abnormalities and neurodevelopmental delay in congenital heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(1):14–24. doi: 10.1002/uog.12526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Rhein M, Buchmann A, Hagmann C. et al. Brain volumes predict neurodevelopment in adolescents after surgery for congenital heart disease. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 1):268–276. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schellen C, Ernst S, Gruber G M. et al. Fetal MRI detects early alterations of brain development in Tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(3):3920–3.92E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masoller N, Sanz-Cortes M, Crispi F. et al. Fetal brain Doppler and biometry at mid-gestation for the early prediction of abnormal brain development at birth in congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(1):65–73. doi: 10.1002/uog.14919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limperopoulos C, Majnemer A, Shevell M I, Rosenblatt B, Rohlicek C, Tchervenkov C. Neurodevelopmental status of newborns and infants with congenital heart defects before and after open heart surgery. J Pediatr. 2000;137(5):638–645. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limperopoulos C, Majnemer A, Shevell M I, Rosenblatt B, Rohlicek C, Tchervenkov C. Neurologic status of newborns with congenital heart defects before open heart surgery. Pediatrics. 1999;103(2):402–408. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donofrio M T, Duplessis A J, Limperopoulos C. Impact of congenital heart disease on fetal brain development and injury. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23(5):502–511. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834aa583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun L, Macgowan C, Sled J G. et al. OC01.01: Reduced fetal cerebral oxygen consumption is associated with smaller brain size in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(S1):1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rychik J, Liu X, Tian Z. OC03.01: Cephalic biometry and cerebrovascular resistance in the fetus with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(S1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvesen KÅ, Lees C, Abramowicz J, Brezinka C, Ter Haar G, Maršál K. Safe use of Doppler ultrasound during the 11 to 13 + 6-week scan: is it possible? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(6):625–628. doi: 10.1002/uog.9025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abu-Rustum R S, Daou L, Abu-Rustum S E. Role of first-trimester sonography in the diagnosis of aneuploidy and structural fetal anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29(10):1445–1452. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.10.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi A C, Prefumo F. Accuracy of ultrasonography at 11-14 weeks of gestation for detection of fetal structural anomalies: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(6):1160–1167. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyett J A, Perdu M, Sharland G K, Snijders R S, Nicolaides K H. Increased nuchal translucency at 10-14 weeks of gestation as a marker for major cardiac defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;10(4):242–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.10040242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyett J, Perdu M, Sharland G, Snijders R, Nicolaides K H. Using fetal nuchal translucency to screen for major congenital cardiac defects at 10-14 weeks of gestation: population based cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318(7176):81–85. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7176.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Rustum R S, Daou L, Abu-Rustum S E. Role of ultrasonography in early gestation in the diagnosis of congenital heart defects. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29(5):817–821. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sotiriadis A, Papatheodorou S, Eleftheriades M, Makrydimas G. Nuchal translucency and major congenital heart defects in fetuses with normal karyotype: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(4):383–389. doi: 10.1002/uog.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira S, Ganapathy R, Syngelaki A, Maiz N, Nicolaides K H. Contribution of fetal tricuspid regurgitation in first-trimester screening for major cardiac defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1384–1391. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821aa720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matias A, Huggon I, Areias J C, Montenegro N, Nicolaides K H. Cardiac defects in chromosomally normal fetuses with abnormal ductus venosus blood flow at 10-14 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;14(5):307–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14050307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timmerman E, Clur S A, Pajkrt E, Bilardo C M. First-trimester measurement of the ductus venosus pulsatility index and the prediction of congenital heart defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(6):668–675. doi: 10.1002/uog.7742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinkovskaya E S, Chaoui R, Karl K, Andreeva E, Zhuchenko L, Abuhamad A Z. Fetal cardiac axis and congenital heart defects in early gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):453–460. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falcon O, Cavoretto P, Peralta C FA, Csapo B, Nicolaides K H. Fetal head-to-trunk volume ratio in chromosomally abnormal fetuses at 11 + 0 to 13 + 6 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(7):755–760. doi: 10.1002/uog.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Votino C, Cos T, Abu-Rustum R. et al. Use of spatiotemporal image correlation at 11-14 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(6):669–678. doi: 10.1002/uog.12548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Votino C, Jani J, Verhoye M. et al. Postmortem examination of human fetal hearts at or below 20 weeks' gestation: a comparison of high-field MRI at 9.4 T with lower-field MRI magnets and stereomicroscopic autopsy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40(4):437–444. doi: 10.1002/uog.11191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombardi C M, Zambelli V, Botta G. et al. Postmortem microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) of small fetuses and hearts. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44(5):600–609. doi: 10.1002/uog.13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardiner H M. Head start for heart babies: perspectives on neurodevelopmental outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(6):616–617. doi: 10.1002/uog.7479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall A C, Levine J, Morash D. et al. Results of in utero atrial septoplasty in fetuses with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28(11):1023–1028. doi: 10.1002/pd.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tworetzky W, McElhinney D B, Marx G R. et al. In utero valvuloplasty for pulmonary atresia with hypoplastic right ventricle: techniques and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):e510–e518. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McElhinney D B, Marshall A C, Wilkins-Haug L E. et al. Predictors of technical success and postnatal biventricular outcome after in utero aortic valvuloplasty for aortic stenosis with evolving hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120(15):1482–1490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.848994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maulik P K, Darmstadt G L. Community-based interventions to optimize early childhood development in low resource settings. J Perinatol. 2009;29(8):531–542. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderveen J A, Bassler D, Robertson C MT, Kirpalani H. Early interventions involving parents to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes of premature infants: a meta-analysis. J Perinatol. 2009;29(5):343–351. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isaacs E B, Fischl B R, Quinn B T, Chong W K, Gadian D G, Lucas A. Impact of breast milk on intelligence quotient, brain size, and white matter development. Pediatr Res. 2010;67(4):357–362. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181d026da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donofrio M T, Massaro A N. Impact of congenital heart disease on brain development and neurodevelopmental outcome. Int J Pediatr. 2010;2010:13. doi: 10.1155/2010/359390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]