Abstract

Background

Persons living with HIV are at a higher risk of cardiovascular disease despite effective antiretroviral therapy and dramatic reductions in AIDS-related conditions. We sought to identify the epidemiology of heart failure (HF) among persons living with HIV in the United States in an era of contemporary antiretroviral therapy.

Methods

Explorys is an electronic healthcare database that aggregates medical records from 23 healthcare systems nationwide. Using systemized nomenclature of medicine - clinical terms (SNOMED-CT), we identified adult patients (age > 18), who had active records over the past year (September 2014–September 2015). We described the prevalence of HF in HIV patients by demographics and treatment and compared them to HIV-uninfected controls.

Results

Overall, there were 36,400 patients with HIV and 12,208,430 controls. The overall prevalence of HF was 7.2% in HIV and 4.4% in controls (RR 1.66 [1.60–1.72], p<0.0001). The relative risk of HF associated with HIV infection was higher among women and younger age groups. Patients receiving antiretroviral therapy had only marginally lower risk (6.4% vs 7.7%, p<0.0001) of HF compared to those who were untreated. Compared to uninfected patients with HF, HIV patients with HF were less likely to receive antiplatelet drugs, statins, diuretics, and ACE/ARBs (p<0.0001 for all comparisons). For patients with HIV and HF, receiving care from a cardiologist was associated with higher use of antiplatelets, statins, betablockers, ACE/ARBs, and diuretics.

Conclusions

Persons with HIV are at higher risk for HF in this large contemporary sample that includes both men and women. Although the prevalence of heart failure is higher in older HIV patients, the relative risk associated with HIV is highest in young people and in women. HIV patients are less likely to have HF optimally treated, but cardiology referral was associated with higher treatment rates.

Keywords: HIV, heart failure, epidemiology

Introduction

With the advent of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV is now a chronic disease, with life expectancy approaching that of uninfected individuals[1]. Patients living with HIV remain at a higher risk of cardiovascular disease despite dramatic reductions in some AIDS-related conditions such as cardiomyopathy[2]. This residual risk in treated HIV infection may be mediated in part through chronic inflammation[3], similar to other inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Heart failure, a common end-result of cardiac disease, appears to be more common among mostly male HIV-infected veterans compared to matched uninfected controls[4]; however, the epidemiology of heart failure in a larger, more generalizable sample of HIV infected patients is unknown. In this report, we sought to estimate the prevalence of HF in patients with HIV and to identify disparities associated with care that might provide opportunities for care improvement.

Methods

Data source

Explorys (Explorys, Inc; Cleveland, Ohio) is a commercial cloud-based database that aggregates data from electronic health records of participating hospital systems. It currently encompasses 23 integrated health systems consisting of 360 hospitals, 315,000 providers, and over 50 million unique patients. It collects data through a healthcare gateway server behind the firewall of participating institutions[5]. The data are collected from billing inquiries, electronic health records, and laboratory systems.

These data aggregates are then de-identified, analyzed, normalized, and standardized into Unified Medical Language Systems (UMLS) ontologies to facilitate searching and indexing. Diagnoses are mapped into systematized nomenclature of medicine-clinical terms (SNOMED-CT) hierarchy, prescriptions mapped to RxNorm, and laboratory test observations mapped to logistical observation identifier names and codes (LOINC), established by the Regenstrief Institute.

The platform is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPAA) and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act standards; hence, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board under a pre-specified policy. The database rounds number of patients to the nearest 10 for an added data protection. This platform has been used for research purposes and has been validated in fields of orthopedics[6], hematology[7], surgery[8], gastroenterology[5], gynecology[9] among others.

Cohort selection and definitions

For the HIV-infected cohort, we selected all patients who were active within the last year (September 2014–September 2015) in the participating hospitals, who were at least 18 years of age and who had a diagnosis of “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection”. For controls, we selected the same age group and excluded patients with “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection”. We identified heart failure using the umbrella term “Heart Failure”. Other used terms correspond to their SNOMED-CT. For nadir CD4, we used the lowest recorded CD4 in Explorys (categorized by groups: <200, 200–500, >500) from 1999–2015.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as numbers and percentages. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to test for differences. Relative risks with 95% confidence intervals were used to report risk differences between compared groups. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Of the 12,244,830 adults who had active records within the past year, we identified 36,400 patients with HIV who fulfilled the selection criteria, and those were compared with 12,208,430 HIV-free controls. Baseline characteristics including distribution by age group are displayed in Table 1. Compared to controls, patients with HIV were more likely to be male, non-caucasian race, and have Medicare or Medicaid. Patients with HIV were more likely to have co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, and hepatitis B and C, They were also more likely to use tobacco, alcohol, cannabinoids, and cocaine.

Table (1).

Demographics and characteristics of study patients

| HIV+ (n=36400) |

HIV− (n=12,208,430) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | <0.0001 | ||

| <65 | 92.7% | 75.8% | |

| ≥65 | 7.3% | 24.2% | |

| Ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||

| Caucasian | 46.5% | 72.3% | |

| African American | 46.9% | 12.2% | |

| Asian | 4.3% | 5.1% | |

| Male (gender) | 68.8% | 40.8% | <0.0001 |

| Insurance type | 0.0% | 0.0% | <0.0001 |

| Private | 44.4% | 55.7% | |

| Medicare | 24.6% | 21.8% | |

| Medicaid | 24.1% | 9.9% | |

| Self Pay | 9.5% | 6.2% | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 17.6% | 13.0% | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 43.5% | 34.4% | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 5.7% | 3.5% | <0.0001 |

| Carotid artery disease | 1.3% | 2.1% | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral Vascular disease | 14.3% | 11.1% | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 9.5% | 8.5% | <0.0001 |

| Hepatitis C | 14.4% | 0.9% | <0.0001 |

| Hepatitis B | 4.8% | 0.2% | <0.0001 |

| BMI | <0.0001 | ||

| Normal [18.5–24.99] | 32.1% | 21.9% | |

| Overweight [25–30] | 31.4% | 26.7% | |

| Obese [>30] | 29.5% | 35.1% |

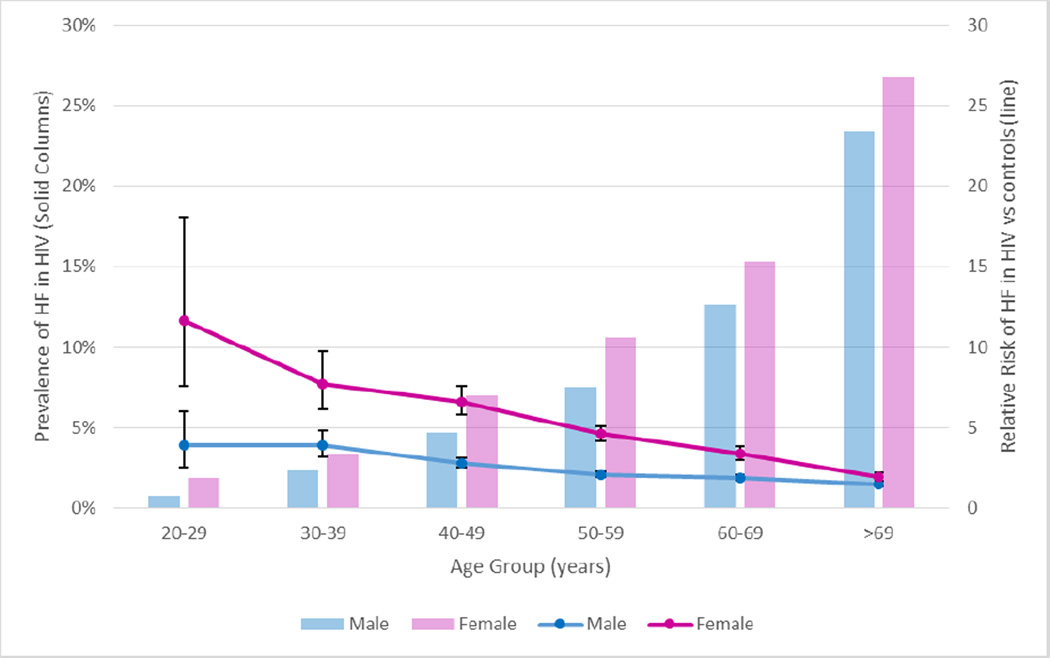

Overall, the prevalence of HF was 7.2% in HIV patients compared with 4.4% in controls [RR (95%CI) of 1.66 (1.60, 1.72); p<0.001]. The relative risk of heart failure associated with HIV infection was highest in the third decade of life (age group of 20–29 years) and decreased with age (Figure 1). Notably, the HIV-associated risk was higher among females [RR 2.28 (2.15, 2.42) vs. RR 1.27 (1.22, 1.33), female vs. male, p<0.001; Figure 1]—a finding that was consistent across all age categories.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of HF in HIV patients (solid columns) and relative risk of HF compared to uninfected controls (lines) by age group and gender

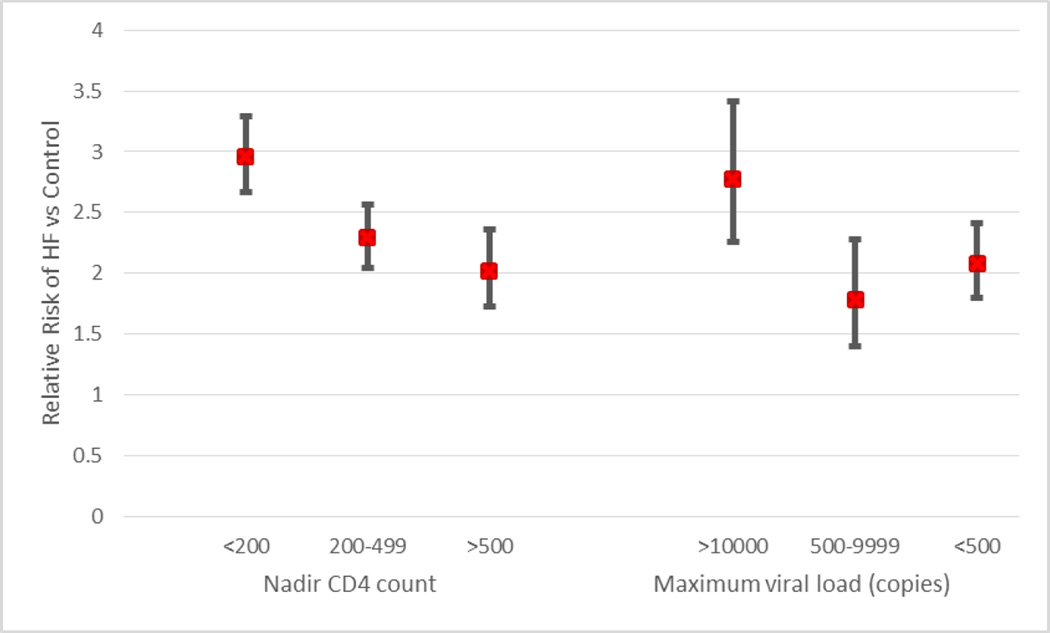

Among HIV-infected individuals with available CD4 counts (n=5700), HF prevalence (12.9% overall in this cohort) was highest among those with CD4 nadir <200 and the prevalence decreased gradually with increasing CD4 nadirs (10.0% in CD4 between 200 and 500, and 8.8% in those with CD4 >500). A similar trend was seen among patients with high HIV viral load and decreased with decreasing viral load, Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Relative Risk of HF by nadir CD4 count and maximum viral load

Among those with HIV infection, the risk was marginally lower in those who were prescribed ART within the last year compared to those who were off therapy [6.4% (6.0, 6.8) vs 7.7% (7.3, 8.0); ART vs. no ART, respectively; p<0.001). The prevalence of HF in patients with HIV was higher in those with CAD [37.9% (36.3, 39.5) vs. 4.0% (3.8, 4.3), CAD vs. no CAD; p<0.001) and in those with proteinuria [22.4% (20.3, 24.6) vs. 6.6% (6.4, 6.9), proteinuria vs. no proteinuria; p<0.001); however, the relative risk of HF associated with HIV infection was higher in patients without CAD [1.28 (1.22, 1.33) vs RR 2.12 (1.91, 2.01), CAD vs. no CAD; p<0.001] and in those without proteinuria [RR 1.37 (1.13, 1.24) vs. 1.58 (1.52, 1.64), proteinuria vs. no proteinuria; p<0.001]. The prevalence of HF was also highest in patients with stage V CKD compared to earlier stages of CKD [57.6% vs. 30.6%, stage 5 vs. stages 1–4; p<0.001].

Among those with HF, patients with HIV were less frequently prescribed diuretics (58.6% vs 68.8%, HIV vs. no HIV; p<0.001), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker (ACE/ARB) use (59.7% vs 62.0%, HIV vs. no HIV; p=0.015), antiplatelet therapy (55.5% vs 62.9%; p<0.001), and beta-blockers (65.8% vs 68.8%, HIV vs no HIV; p=0.001) but rates of cardiology visits were similar (66.2% vs 65.5%, HIV vs no HIV, p=0.5). Among those with HIV and HF, having a cardiology visit was associated with higher rates of diuretic use [RR 1.89 (1.73, 2.07)], ACE/ARB [RR 1.85 (1.69, 2.02)], beta-blockers [RR 1.82 (1.68, 1.97)], and antiplatelets [RR 2.06 (1.87, 2.28)].

Discussion

Our report provides a broad epidemiologic snapshot of the risk of heart failure among patients with HIV in the United States. Overall, the risk of heart failure was nearly two-fold higher in HIV patients compared with uninfected controls. This risk associated with HIV is present across a broad spectrum of age groups and for both males and females. Patients with HIV and HF may be undertreated for HF, but specialty cardiologist care is associated with higher rates of HF treatment.

Heart failure remains a significant cause of non-AIDS morbidity and mortality among patients with HIV. Theories regarding the excess risk of heart failure in this population include a direct effect of HIV on the myocardium, autoimmunity, chronic inflammation, coronary artery disease, or side effects of ART[10]; however, data from the modern era of effective ART are relatively limited. A recent meta-analysis found a prevalence of 8.3% (95%CI 2.2–14%) left ventricular systolic dysfunction and 43% (95% CI 31–55%) diastolic dysfunction among 2,242 subjects from 11 studies with >75% of subjects on combination ART[11]. The limited epidemiologic evidence for an elevated risk of clinical HF comes from the Veteran Aging Cohort Study Virtual Cohort (VACS-VC)[4]. In this study of 8486 HIV-infected patients, the hazard ratio for HF was 1.81 (95%CI 1.39–2.36)[4] after adjustment for traditional risk factors. Interestingly, this is very similar to our finding of RR 1.66 (1.60, 1.72). We further show that this risk is highest in younger patients and in females. Importantly, the HIV-associated increase in risk was highest in patients without coronary artery disease or proteinuria. While HIV infection is associated with higher risk of both myocardial infarction and kidney disease[12, 13], our findings would suggest that there are additional mediators of risk beyond these two important factors.

The gender difference in the risk of HF merits further comment. The overall burden of disease (AIDS and non-AIDS) is thought to be higher in females, and females may have less improvement with ART therapy[14]. Epidemiologic studies of the VACS cohort have evaluated risk of CVD separately for males and females. In a smaller number of 710 HIV infected and 1543 HIV uninfected female veterans followed from 2003 to 2009, HIV was associated with a higher risk of total CVD events [HR 2.8 (95% CI 1.7, 4.6)][15]. Although the number of events was small (n=86), over half were heart failure events. Furthermore, HIV infection was associated with higher incidence of HF excluding CVD [incidence rate ratio 2.5 (95%CI 1.5, 4.5)]. Our study confirms these findings in a larger and more contemporary population of HIV-infected women, and extends them by directly comparing the risk ratios between men and women. Further study is needed to confirm whether HIV is associated with a greater risk of HF in women compared to men and to explore gender differences in mechanisms of HIV-associated heart failure. Although women account for only 1 of 4 people living with HIV in the United States, they comprise greater than half of all infections globally[16]. Furthermore, eighty percent of women with HIV over 15 years old live in sub-Saharan Africa[16] where risk factors for HF may differ significantly from the USA or Europe.

In this study, patients with HIV were receiving different therapies for HF compared to those without HIV. Specifically, HIV infected patients were less likely to receive diuretics, ACE/ARB, beta-blockers, and antiplatelets compared to their HIV uninfected counterparts. Prior studies have suggested systematically lower use of aspirin[17, 18] and statins[19] for primary and secondary prevention in HIV patients compared to uninfected controls; however, this trend has been reversed in recent years in one integrated healthcare system, possibly due to heightened awareness of CVD risk among HIV providers[20]. Interestingly, patients who were referred to specialty cardiology care had higher treatment rates. We are unable to further explore the reasons for these treatment disparities, but there are several possible explanations. Our findings may reflect referral bias (e.g. patients with ischemic heart disease, systolic heart failure or more advanced heart failure may be more likely to be referred to cardiology) or confounding by indication (e.g. less ischemic heart disease in HIV patients leading to less statin and anti-platelet use). On the other hand, it is possible that some clinicians may be reluctant to treat HF and its risk factors in patients with HIV, because of concerns for drug interactions with HAART (especially statins). Patients with HIV, should receive guideline-directed medical therapy according to the AHA/ACC guidelines for heart failure management[21].

Our findings that HF prevalence is highest among those with lower nadir CD4 T-cell count and history of uncontrolled viremia are consistent with analyses of the Veterans Aging Cohort Study[4]. Similar findings have been described for coronary and cerebrovascular events in patients with HIV[20, 22, 23]. Uncontrolled viral replication is associated with chronic inflammation and immune activation, which may mediate the observed increase in cardiovascular events [23]. It is unclear, however, if interventions that aim to reduce chronic inflammation in this cohort will lead to reduction in risk of HF[3].

Limitations

This is a retrospective study of a large national registry. This study could not identify the etiology of HF, systolic or diastolic, ischemic or non-ischemic. We also could not ascertain to what degree the higher prevalence of HF was due to HIV infection itself or confounding factors (e.g smoking, alcohol, etc). Regardless, this study examines a very large sample size and should be considered as hypothesis generating. It is unlikely that such power could be reached in prospective studies.

Conclusions

Persons living with HIV are at higher risk for HF than the general population and HF prevalence is higher in older patients and females. The relative risk is highest among young patients and decreases with age. HIV-infected patients are less likely to have HF optimally treated with diuretics, statins, and antiplatelets. Cardiology referral was associated with higher treatment rates.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (K23 HL123341 to CTL).

Abbreviations

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- HF

Heart Failure

- CAD

Coronary Artery Disease

- ART

Antiretroviral Therapy

- RR

Relative Risk

- CI

Confidence Interval

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: No conflict of interest pertinent to this article.

Part of the contents of this manuscript were presented as a Rapid Fire oral presentation at the 19th Annual Scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America (September 26–29, National Harbor, MD).

References

- 1.Wada N, Jacobson LP, Cohen M, French A, Phair J, Munoz A. Cause-specific mortality among HIV-infected individuals, by CD4(+) cell count at HAART initiation, compared with HIV-uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2014;28:257–265. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemkens LG, Bucher HC. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1373–1381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serhal M, Longenecker C. Preventing Heart Failure in Inflammatory and Immune Disorders. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2014;8:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12170-014-0392-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt AA, Chang CC, Kuller L, Goetz MB, Leaf D, Rimland D, et al. Risk of heart failure with human immunodeficiency virus in the absence of prior diagnosis of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:737–743. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maradey-Romero C, Prakash R, Lewis S, Perzynski A, Fass R. The 2011–2014 prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the elderly amongst 10 million patients in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 doi: 10.1111/apt.13171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfefferle K, Gil K, Fening S, Dilisio M. Validation study of a pooled electronic healthcare database: the effect of obesity on the revision rate of total knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24:1625–1628. doi: 10.1007/s00590-014-1423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaelber DC, Foster W, Gilder J, Love TE, Jain AK. Patient characteristics associated with venous thromboembolic events: a cohort study using pooled electronic health record data. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2012;19:965–972. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanmugam VK, Fernandez S, Evans KK, McNish S, Banerjee A, Couch K, et al. Postoperative wound dehiscence: predictors and associations. Wound Repair Rege. 2015 doi: 10.1111/wrr.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Mete MM, St Clair C, Iglesia CB. Practice patterns of general gynecologic surgeons versus gynecologic subspecialists for concomitant apical suspension during vaginal hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. South Med J. 2015;108:17–22. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remick J, Georgiopoulou V, Marti C, Ofotokun I, Kalogeropoulos A, Lewis W, et al. Heart Failure in Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Future Research. Circulation. 2014;129:1781–1789. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerrato E, D'Ascenzo F, Biondi-Zoccai G, Calcagno A, Frea S, Grosso Marra W, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in pauci symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus patients: a meta-analysis in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1432–1436. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:614–622. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Althoff KN, McGinnis KA, Wyatt CM, Freiberg MS, Gilbert C, Oursler KK, et al. Comparison of risk and age at diagnosis of myocardial infarction, end-stage renal disease, and non-AIDS-defining cancer in HIV-infected versus uninfected adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:627–638. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackstock OJ, Tate JP, Akgun KM, Crystal S, Duggal M, Edelman EJ, et al. Sex disparities in overall burden of disease among HIV-infected individuals in the Veterans Affairs healthcare system. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(Suppl 2):S577–S582. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Womack JA, Chang CC, So-Armah KA, Alcorn C, Baker JV, Brown ST, et al. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease in women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001035. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HIV/AIDS JUNPo. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. The gap report. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suchindran S, Regan S, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK, Triant VA. Aspirin Use for Primary and Secondary Prevention in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:ofu076. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkholder GA, Tamhane AR, Salinas JL, Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Westfall AO, et al. Underutilization of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease among HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1550–1557. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freiberg MS, Leaf DA, Goulet JL, Goetz MB, Oursler KK, Gibert CL, et al. The association between the receipt of lipid lowering therapy and HIV status among veterans who met NCEP/ATP III criteria for the receipt of lipid lowering medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:334–340. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein DB, Leyden WA, Xu L, Chao CR, Horberg MA, Towner WJ, et al. Declining relative risk for myocardial infarction among HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative individuals with access to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1278–1280. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus JL, Leyden WA, Chao CR, Chow FC, Horberg MA, Hurley LB, et al. HIV infection and incidence of ischemic stroke. AIDS. 2014;28:1911–1919. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverberg MJ, Leyden WA, Xu L, Horberg MA, Chao CR, Towner WJ, et al. Immunodeficiency and risk of myocardial infarction among HIV-positive individuals with access to care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:160–166. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]