Abstract

Key points

Regulation of ion channel function during repeated firing of action potentials is commonly observed in excitable cells. Recently it was shown that muscle activity is associated with rapid, protein kinase C (PKC)‐dependent ClC‐1 Cl− channel inhibition in rodent muscle.

While this PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition during muscle activity was shown to be important for the maintenance of contractile endurance in rat muscle it is unknown whether a similar regulation exists in human muscle.

Also, the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition are unclear.

Here we present the first demonstration of ClC‐1 inhibition in active human muscle fibres, and we determine the changes in ClC‐1 gating that underlie the PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition in active muscle using human ClC‐1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

This activity‐induced ClC‐1 inhibition is suggested to represent a mechanism by which human muscle fibres maintain their excitability during sustained activity.

Abstract

Repeated firing of action potentials (APs) is known to trigger rapid, protein kinase C (PKC)‐dependent inhibition of ClC‐1 Cl− ion channels in rodent muscle and this inhibition is important for contractile endurance. It is currently unknown whether similar regulation exists in human muscle, and the molecular mechanisms underlying PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition are unclear. This study first determined whether PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition exists in active human muscle, and second, it clarified how PKC alters the gating of human ClC‐1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. In human abdominal and intercostal muscles, repeated AP firing was associated with 30–60% reduction of ClC‐1 function, which could be completely prevented by PKC inhibition (1 μm GF109203X). The role of the PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition was evaluated from rheobase currents before and after firing 1000 APs: while rheobase current was well maintained after activity under control conditions it rose dramatically if PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition had been prevented with the inhibitor. This demonstrates that the ClC‐1 inhibition is important for maintenance of excitability in active human muscle fibres. Oocyte experiments showed that PKC activation lowered the overall open probability of ClC‐1 in the voltage range relevant for AP initiation in muscle fibres. More detailed analysis of this reduction showed that PKC mostly affected the slow gate of ClC‐1. Indeed, there was no effect of PKC activation in C277S mutated ClC‐1 in which the slow gate is effectively locked open. It is concluded that regulation of excitability of active human muscle fibres relies on PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition via a gating mechanism.

Key points

Regulation of ion channel function during repeated firing of action potentials is commonly observed in excitable cells. Recently it was shown that muscle activity is associated with rapid, protein kinase C (PKC)‐dependent ClC‐1 Cl− channel inhibition in rodent muscle.

While this PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition during muscle activity was shown to be important for the maintenance of contractile endurance in rat muscle it is unknown whether a similar regulation exists in human muscle.

Also, the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition are unclear.

Here we present the first demonstration of ClC‐1 inhibition in active human muscle fibres, and we determine the changes in ClC‐1 gating that underlie the PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition in active muscle using human ClC‐1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

This activity‐induced ClC‐1 inhibition is suggested to represent a mechanism by which human muscle fibres maintain their excitability during sustained activity.

Abbreviations

- λ

fibre length constant

- 9‐AC

9‐anthracenecarboxylic acid

- AP

action potential

- D

fibre diameter

- Gm

membrane conductance per square centimetre of surface membrane

- GCl

chloride conductance

- KR

Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate solution

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMA

phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate

- Po

overall open probability of the ClC‐1 channel

- Pof

open probability of the fast gate

- Pos

open probability of the slow gate

- ri

intracellular resistance per unit fibre length

- Ri

specific cytosolic resistivity

- Rin

fibre input resistance

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- ΔV

magnitude of the membrane voltage response to constant current injections

- WT

wild‐type

Introduction

A hallmark of mature skeletal muscle fibres is an intrinsic high resting membrane conductance (G m) that effectively stabilizes the membrane potential and thereby greatly affects the excitability of muscle fibres. While G m reflects the function of both K+ and Cl− channels, ClC‐1 Cl− ion channels contribute 80–90% of G m and therefore have a prominent role in determining muscle excitability (Bryant & Morales‐Aguilera, 1971; Palade & Barchi, 1977; Kwieciński et al. 1984; Pedersen et al. 2005). Indeed, the importance of ClC‐1 channels is clearly demonstrated by the skeletal muscle hyperexcitability in patients suffering from myotonia congenita, a rare inherited disorder caused by loss of function mutations in the gene coding for ClC‐1 (McComas & Mrozek, 1968; Koch et al. 1992; Pusch, 2002).

The ClC‐1 channel is a member of a large gene family comprising Cl−‐selective channels and Cl−/H+ exchangers (Steinmeyer et al. 1991; Miller, 2006; Jentsch, 2008; Feng et al. 2010). The functional ClC‐1 channel is a homodimer with each subunit forming a separate ion conduction pathway (protopore) that, when open, allows Cl− to transverse the membrane (Dutzler et al. 2002). The opening and closing of the protopores are controlled by two distinct voltage‐gated mechanisms: Each pore has its own independent gate that is referred to as the ‘fast gate’ because its fast kinetics enable this channel to open in less than 1 ms at positive potentials. In addition, both pores can also be simultaneously gated by a gate that, due to its slower kinetics, is called the ‘slow’ gate (Saviane et al. 1999).

While a number of cellular signals can modulate ClC‐1 function, PKC has been shown to be a key regulator of ClC‐1 (Chen & Jockusch, 1999; Rosenbohm et al. 1999), presumably by phosphorylating one or more residues in the intracellular C‐terminal region of the channel (Hsiao et al. 2010). This PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 regulation was first discovered when phorbol esters were observed to greatly reduce G m in both mouse and rat muscle fibres (Brinkmeier & Jockusch, 1987; Bryant & Conte‐Camerino, 1991; Tricarico et al. 1991). Later, PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 regulation was shown to be involved in the G m reductions that can be induced by several drugs and hormones, including statin, angiotensin and ghrelin (Pierno et al. 2003, 2009; Cozzoli et al. 2014). A more physiological role of PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition was discovered when repeated firing of APs in rat muscle fibres were found to cause a more than 50% reduction in G m that was sensitive to PKC inhibition (Pedersen et al. 2009 a,b). These results additionally revealed that the PKC was activated by the Ca2+ released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which was taken to indicate the involvement of conventional PKC isoforms (Pedersen et al. 2009 b). The PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition was later shown to be important for maintenance of fibre excitability and function during intense activity in rat muscles (de Paoli et al. 2013). While it has also been reported that comparable ClC‐1 regulation is present in mouse muscle (Riisager et al. 2014), it is unknown whether similar PKC‐dependent regulation of ClC‐1 channels takes place in active human skeletal muscle. Based on this, the present study examined the regulation of ClC‐1 channels in active human rectus abdominis and intercostal muscles. The study further aimed to determine the molecular mechanism behind PKC‐induced regulation of ClC‐1 by exploring the effects of PKC activation on the fast and slow gating of human ClC‐1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

Methods

Ethical approval

Some of the experiments in this study were performed on isolated, intact human muscle fibres. The isolation and use of human skeletal muscle was approved by the Danish Ethics Committee, Region Midtjylland, Comité I (reference number 1‐10‐72‐20‐13). Experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects were informed of the purpose and risks, and provided informed consent. Part of the isolated muscle tissue from which bundles of muscle fibres were isolated for the present study was also the source for fibre bundles used in another project (Skov et al. 2015).

Isolation and preparation of human muscle tissue

Human abdominal muscle fibres were isolated as described elsewhere (Skov et al. 2015). In short, rectus abdominis muscle tissue was obtained from subjects admitted for planned aortic aneurysm surgery. Intact bundles of well‐defined muscle fibres measuring approx. 8 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm were isolated from patients during standard transverse laparotomy or longitudinal abdominal incision at the linea alba during open abdominal aortic aneurysm or thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery, respectively. The muscle fibres remained attached to the tendinous insertions at both ends.

Human intercostal muscle fibres were isolated from patients undergoing anterior thoracotomy in relation to lung surgery (non‐small cell lung cancer). Patients with a short, broad thoracic form (pyknic type) were not included to ensure appropriate length of the intercostal muscle fibres. The incision was made along the inframammary crease from sternal edge to anterior axillary line. Dissection of the soft tissues was continued to the pectoralis fascia. The caudal portion of the pectoralis muscle was mobilized off the ribs giving access to the fourth and fifth ribs. Laterally, serratus muscle was split along the course of its fibres. Diathermy was used for most of the dissection. The intercostal fibres were sampled in the area of the mid‐clavicular line, between the fourth and fifth ribs. The periosteum of the fourth and fifth ribs was incised longitudinally with a scalpel for a length of 2 cm. With a small periosteal elevator the external intercostal muscle was freed from both ribs and the muscle was divided with scissors along the course of its fibre. This ensured a well‐defined muscle specimen with the fibres attached to periosteum at both ends.

All tissue samples were placed in a Hepes‐based solution immediately after isolation. Hepes solution contained (mm): 5 Na‐Hepes, 122 NaCl, 9 HCl, 2.8 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.27 CaCl2, and 5.0 d‐glucose, pH 7.4. The samples were then transported to the laboratory (taking less than 30 min) where they were washed in standard Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate solution (KR) before bundles of muscle fibres were isolated and placed at resting length in an experimental chamber continuously perfused (25 ml min−1) with KR solution (pH 7.4) at 30°C containing (mm): 122 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.8 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.27 CaCl2, and 5.0 d‐glucose. KR solution was maintained at 30°C and continuously equilibrated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.4.

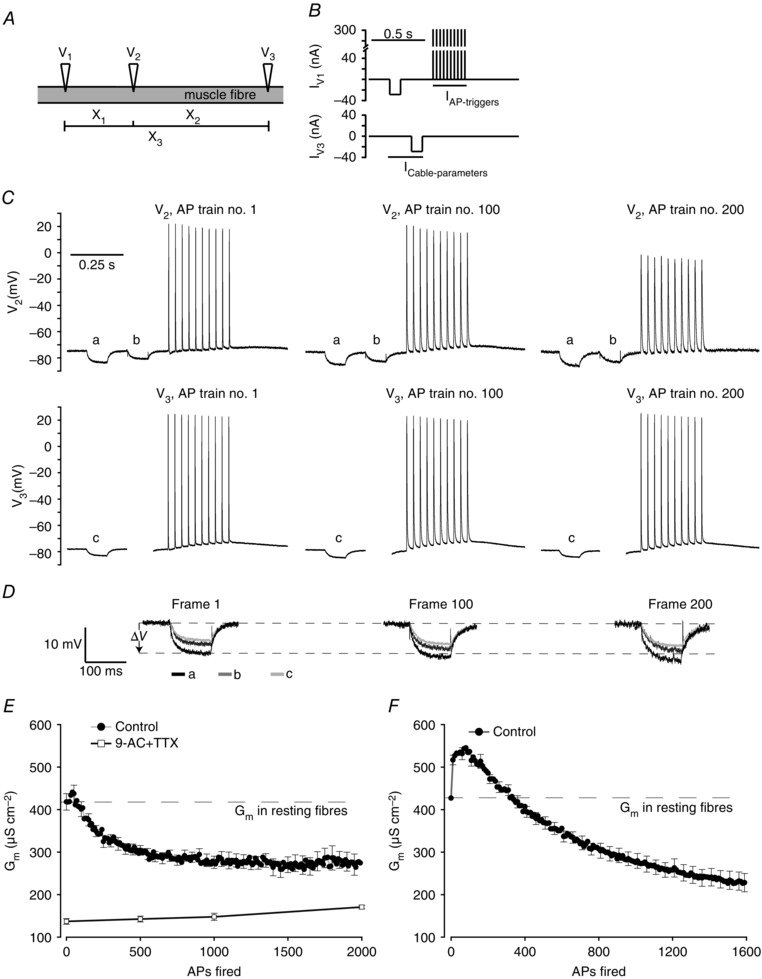

Measurement of cable parameters in human muscle fibres

Measurements of cable parameters from muscle fibres were performed using a previously described setup and method (Riisager et al. 2014). In short, to determine G m in AP‐firing fibres, three electrodes (V1–V3) were inserted into the same fibre with known inter‐electrode distances of 0.4–0.5 mm (V1–V2, X1) and 1.2–1.5 mm (V1–V3, X3). By keeping the distance of V2–V3 at approximately twice the V1–V2 distance (Fig. 1 A), and by switching the current injection between V1 and V3, this configuration made it possible to obtain the membrane potential responses to constant current injection at three inter‐electrode distances (a, b and c, Fig. 1 C) without moving the electrodes. The current injections used for determination of cable parameters had an amplitude of −30 nA and a duration of 100 ms. Trains of APs (30 Hz, 10 pulses per train) were triggered by injection of large‐amplitude currents through V1 (300 nA, 1 ms). Fibres with resting membrane potential that depolarized beyond −60 mV during experiments were omitted from analysis. To prevent muscle fibre contraction, the myosin–actin interaction was inhibited by 25 μm blebbistatin added to the perfusion solution (Pedersen et al. 2009 a). To calculate G m, the transfer resistance at the three inter‐electrode distances were plotted against inter‐electrode distance and fitted to a cable equation that applies to cells of infinite length with a membrane represented by a parallel resistor–capacitor circuit (Hodgkin & Rushton, 1946):

| (1) |

where ΔV(x) represents the steady‐state membrane potential deflection at position x in response to constant current injected at position x = 0.

Figure 1. Determination of Gm in human skeletal muscle fibres between intermittently fired trains of APs using three intracellular electrodes .

A, illustration of the positioning of three intracellular microelectrodes (V1, V2, V3) placed in an intact muscle fibre. This arrangement allowed three inter‐electrode distances to be identified (X1, X2, X3). All three electrodes recorded the membrane potential while V1 and V3 also injected current. B, one repetition of current injection through V1 (IV1) and V3 (IV3) consisting of small‐amplitude hyperpolarizing current pulses (−30 nA, 100 ms) used for determination of cable parameters (I Cable‐parameters) and a train of large‐amplitude depolarizing current pulses through V1 (300 nA, 30 Hz, 10 pulses, 1 ms) used to trigger APs (I AP‐triggers). C, membrane potential recordings from electrodes V2 and V3 during the first (AP 1–10), 100th (AP 991–1000) and 200th (AP 1991–2000) run of the current protocols in a representative human abdominal muscle fibre. D, enlargements of the voltage deflections shown in C that were used to determine cable parameters. E, average G m in human abdominal fibres during experiments as illustrated for the fibre in C and D in the absence (n = 18) or in the presence (n = 8) of 100 μm 9‐AC + 10 nm TTX. Each repetition of the current protocols gave one determination of cable parameters. F, changes in G m during repetitive excitations of AP trains (30 Hz, 10 pulses every 1.4 s) in human intercostal muscle fibres determined from measurements of R in using two intracellular electrodes placed at close proximity in the same fibre (Pedersen et al. 2009 b) (n = 8). n represents number of fibres and average data are presented as means ± SEM. For clarity, only every fifth error bar is shown.

From these fits, the input resistance (R in) and length constant (λ) were obtained and used to calculate the membrane resistance per unit length of fibre (r m) and the intracellular resistance per unit length of fibre (r i) by the following relations (Jack et al. 1975):

| (2) |

| (3) |

By assuming a constant internal resistivity (R i) of 156 Ω cm (adopted from Lipicky et al. 1971) and temperature correction using a Q 10 value of 1.37 (Hodgkin & Nakajima, 1972) the fibre diameter (D) and G m could be obtained from (Fink & Lüttgau, 1976):

| (4) |

| (5) |

In a series of experiments with intercostal muscles a two‐electrode technique was used. With this approach two electrodes were inserted at close proximity and from direct measurements of R in during the activity it is possible to estimate G m during AP firing (Pedersen et al. 2009 b). With this approach it is necessary to know G m in fibres not engaged in AP firing activity, which here was taken as the G m that was determined in the resting human abdominal muscle fibres (427 μS cm−2, Table 1) as this value is very similar to G m in human intercostal muscle fibres (Lipicky, 1979; Kwieciński et al. 1984). It has recently been shown that the two‐ and three‐electrode methods give very similar results (Riisager et al. 2014).

Table 1.

Cable parameters from human abdominal muscle fibres not engaged in AP firing activity

| Group | n | V m (mV) | λ (mm) | R in (MΩ) | D (μm) | G m (μS cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 67 | −74 ± 1 | 1.66 ± 0.04 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 69 ± 2 | 427 ± 16 |

| 1 μm GF109203X | 42 | −73 ± 1 | 1.65 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 72 ± 3 | 465 ± 28 |

| 100 μm 9‐AC + 10 nm TTX | 12 | −75 ± 1 | 3.45 ± 0.23 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 89 ± 4 | 131 ± 13 |

Electrophysiological parameters of skeletal muscle fibres from human abdominal muscle. λ and R in were determined using a three‐electrode method (Riisager et al. 2014): the magnitude of steady‐state voltage deflections in response to constant current injections, measured at 3 distances, were plotted against inter‐electrode distance and then fitted to a two‐parameter exponential decaying function whereby λ and R in could be obtained. G m and D were calculated from λ and R in using an assumed R i of 156 Ω cm. n represents number of fibres in each group and values are presented as means ± SEM.

Glass pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries and backfilled with 2 m potassium citrate (electrode resistances around 15 MΩ). Two electrodes were connected to a TEC‐05X two‐electrode clamp system (NPI, Tamm, Germany) while the third electrode was connected to a SEC‐05X single electrode amplifier system (NPI, Tamm, Germany). Experimental protocols for current injections and data acquisition were controlled using Signal 5 and a Power1401 interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Further analysis and fitting of data was done using scripts written in Signal 5.

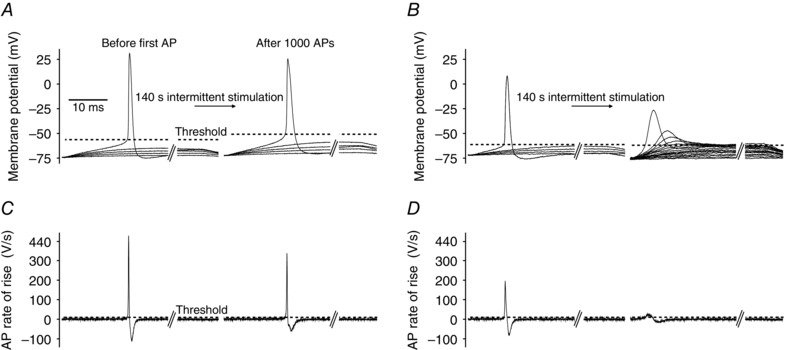

Muscle fibre excitability and action potential threshold

Fibre excitability was judged from measurements of rheobase currents determined as the minimum amplitude of 50 ms‐long depolarizing square current that was needed to trigger one AP in the impaled fibre. AP voltage threshold was judged from the rate of rise of the AP waveform, by determining the membrane potential at which the derivative of voltage with respect to time, dV/dt, exceeded 10 V s−1 (Novak et al. 2015).

Preparation of mRNA used for oocyte injection

cDNA of the human wild‐type (WT) ClCN1 gene was constructed in the pTLN vector (Tseng et al. 2007), and the corresponding C277S mutation was made using a polymerase chain reaction‐based QuickChange II site‐directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). mRNA of the desired construct used to inject oocytes was synthesized using a mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 transcription kit (Ambion) and confirmed by commercial DNA sequencing services.

Oocyte preparation and injection of mRNA

Mature female Xenopus laevis were anaesthetized with 0.15% tricaine methanesulfonate (Argent Labs, Redmond, WA, USA) buffered with NaHCO3 to the level of no responses to toe pinches, and a part of the ovarian lobe was removed from the abdominal cavity through a small, 0.5–1 cm, incision. Stage V–VI oocytes were isolated after deflocculating with 1 mg ml−1 type I collagenase in OR‐2 solution for 90 min and subsequent washing. OR‐2 solution contained (mm): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2 and 5 Na‐Hepes, pH 7.4 (pH titrated with NaOH). Oocytes were injected with 50 nl (corresponding to 3–5 ng) of human ClC‐1 mRNA dissolved in distilled water using an automated microinjector (Nanoliter Injector, WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) and incubated for 2–3 days at 19°C before two‐electrode voltage clamp experiments in ND96 solution containing (mm): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, and 5 Na‐Hepes, pH 7.4, plus 0.2 mg ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin (pH titrated with NaOH). The oocyte incubation medium was changed daily.

Two‐electrode voltage clamp measurements

Total membrane currents were measured from injected oocytes using a two‐electrode voltage clamp amplifier (OC‐725C, Warner Instruments/Harvard Apparatus, Hamden, CT, USA) at room temperature. Current acquisition and membrane potential control was performed using a Digidata 1322 A/D converter controlled by pCLAMP 9 (Axon Instruments/Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Data analysis was done offline using pCLAMP 9 and SigmaPlot 12.5 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Microelectrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries with a micropipette puller (PC‐10, Narishige, Amityville, NY, USA) and backfilled with 3 m KCl resulting in electrode resistances of 0.1–0.3 MΩ. During experiments oocytes were placed in a ∼1 ml recording chamber containing ND96.

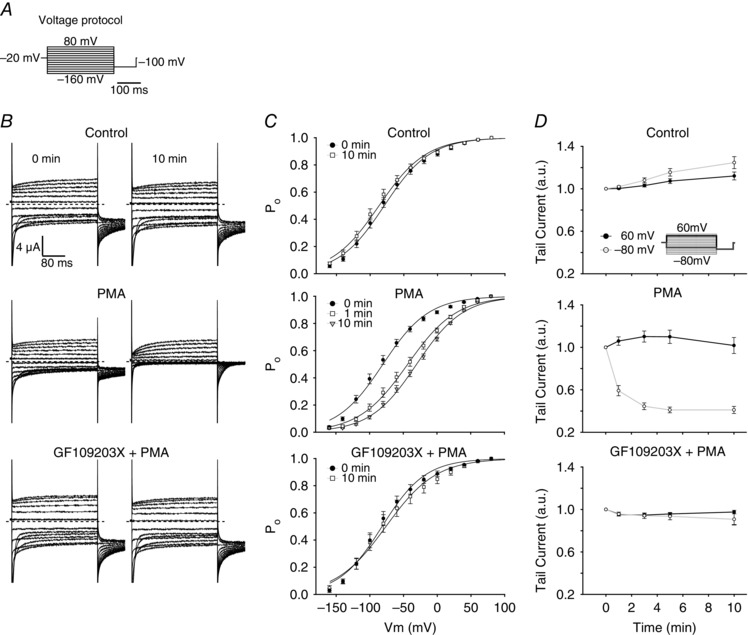

To activate currents, the membrane potential was stepped from a −20 mV holding potential to various test voltages ranging from +80 to −160 mV in 20 mV steps of 300 ms duration, followed by a 100 ms tail voltage at −100 mV (protocol A, see Fig. 4 A). In order to determine the relative overall open probability (P o), the initial tail current at the beginning of the tail voltage was for each oocyte determined by extrapolation of a double‐exponential function fitted to the current data for each test voltage. This initial current value was then normalized to the maximal value of the initial tail current obtained following the most positive test voltage. For each oocyte, the data were plotted as a function of test voltages and fitted to the following Boltzmann function:

| (6) |

Figure 4. Effects of PKC activation and inhibition on the open probability of human ClC‐1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes .

A, illustration of the voltage protocol used to evoke currents through ClC‐1 expressed in oocytes by the two‐electrode voltage clamp. The voltage protocol consisted of 300 ms test voltages between +80 and −160 mV from a holding voltage of −20 mV, followed by a tail pulse at −100 mV. B, representative whole cell current traces from oocytes expressing WT ClC‐1 channels before and 10 min after the incubation solution (ND96) was changed to contain: top panel, ND96 only (negative control); middle panel, ND96 + 200 nm PMA; bottom panel, ND96 + 200 nm PMA + 1 μm GF109203X. Oocytes treated with GF109203X were incubated in ND96 containing 1 μm GF109203X 60 min prior to start of experiment. Dashed lines represent zero current. C, plots of the initial tail currents normalized to the initial tail current at the most positive voltage step at the indicated time points. The normalized current reflects overall open probability of expressed ClC‐1 channels (P o) (top: n = 17, middle: n = 19, bottom: n = 6). Continuous lines represent fits of eqn (6) to the experimental data points. D, average values of the relative changes in initial tail currents following the +60 and −80 mV test voltages at the indicated time points after solution exchange. Data in C and D are given as means ± SEM. n represents the number of oocytes. a.u., arbitrary units.

where I min is a constant current offset, V 1/2 is the half‐maximal activation voltage, and k is a slope factor.

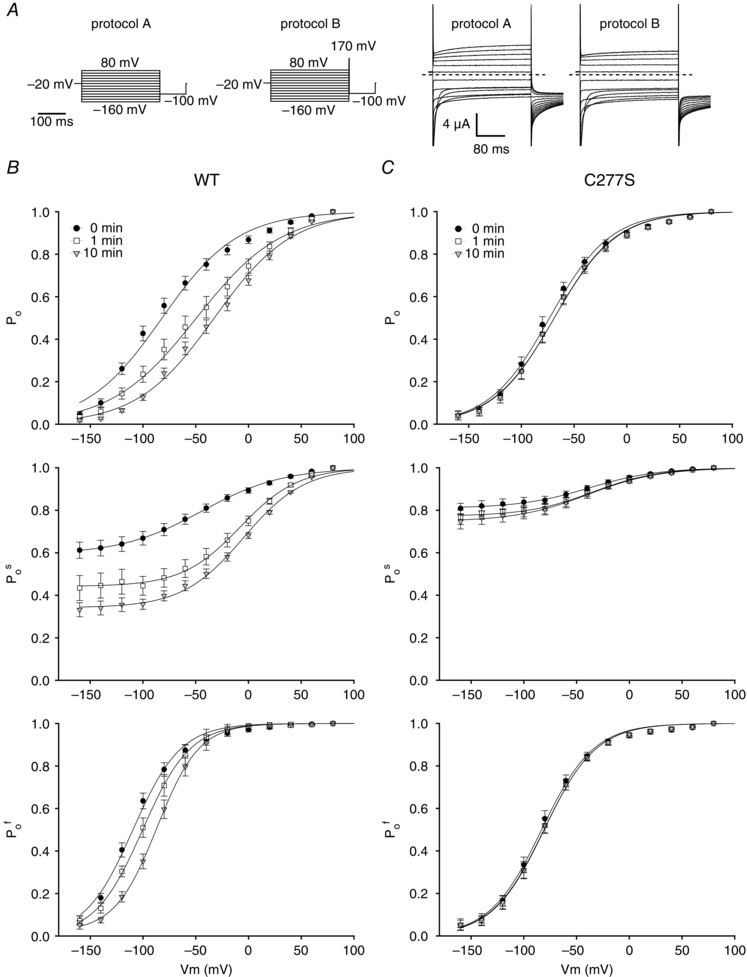

The open probability of the slow gate (P o s) was assessed using a protocol that was identical to protocol A (protocol B, see Fig. 5 A), except that a large but short voltage step was inserted between the test voltage and the tail voltage by setting the command voltage to +170 mV for 1 ms. During experiments, protocol B was applied immediately following protocol A. The rationale for inserting the short and strongly depolarizing pulse after the test voltage in protocol B was to maximize the open probability of the fast gate (P o f) while not altering the slow gate (Accardi & Pusch, 2000; Duffield et al. 2003; Bennetts et al. 2005). When this is obtained, P o f can be estimated by dividing the value of P o from protocol A by P o s from protocol B. To ensure that the fast gate was actually fully activated by the 1 ms strongly depolarizing command voltage inserted after the test voltage in protocol B the speed of the oocyte voltage clamp was evaluated from the time constant of the membrane charging (τ) as estimated from fits of the falling phase of the capacitive transients during the different voltage steps in the protocols. An average τ of 0.48 ± 0.04 ms (n = 17 oocytes) was estimated from oocytes expressing ClC‐1. With this time constant the membrane potential of the oocytes would have reached approximately 134 mV at the end of the 1 ms command pulse to +170 mV when applied from a holding potential of −120 mV and approximately 0.3 ms would have been spent above +100 mV. Since Accardi & Pusch (2000) have shown that the activation of the fast gate at +100 mV proceeds with a time constant of around 0.05–0.07 ms it must be expected that with 0.3 ms above +100 mV the fast gate would indeed be fully activated.

Figure 5. Effects of 200 nm PMA on fast and slow gating in WT and C277S ClC‐1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes .

A, voltage protocols used for direct measurements of overall (P o) and slow (P o s) gate open probability analysis (left panels). Protocols A and B differed by the inclusion of a 1 ms activation pulse to +170 mV after the test voltage. Also included are representative whole cell current traces elicited by protocols A and B in an oocyte expressing WT ClC‐1 (right panels). The 1 ms pulse included in protocol B fully activates the fast gate and the following initial tail currents recorded at −100 mV reflect only P o s. P o f was then obtained by dividing P o for a given test voltage by its corresponding P o s. Panels in B show the average effect of 200 nm PMA on relative changes in P o, P o s and P o f (top, middle and bottom) of expressed WT ClC‐1 at the indicated time points (n = 9). C, as B but for C277S (n = 9). Data in B and C are given as means ± SEM. n represents the number of oocytes.

Solution exchange

Solution exchange during oocyte experiments was achieved using a valve‐controlled perfusion system (VC‐8, Warner Instruments/Harvard Apparatus). In experiments using phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA) or PMA and GF109203X, the bath solution (ND96) was exchanged (at time 0) with ND96 containing 200 nm PMA or 200 nm PMA and 1 μm GF109203X, respectively. In control experiments the bath solution was exchanged (at time 0) with ND96 without additions.

Chemicals

All chemicals were of analytical grade. Bisindolylmaleimide I (GF109203X), Hepes, 9‐anthracenecarboxylic acid (9AC), phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA), 4α‐phorbol 12,13‐didecanoate (4αPDD; inactive phorbol ester), DMSO, collagenase type 1A (mix of Sigma and Life type 1A) and tetrodotoxin (TTX) were from Sigma‐Aldrich (Copenhagen, Denmark). Tricaine methanesulfonate was from Argent Chemical Laboratories, Inc. and blebbistatin from Toronto Research Chemicals Inc. (Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

Stock solutions of chemicals were prepared in DMSO and stored at –20°C. Total concentration of DMSO in solutions during experiments was less than 0.2%.

Statistical analysis

All average data are presented as means ± SEM. Significant difference between groups was ascertained using Student's two‐tailed t test for paired or non‐paired observations. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 regulation in human muscle fibres during AP firing activity

To determine whether ClC‐1 channels in human muscle fibres are regulated during muscle activity, G m was measured in human abdominal and intercostal muscle fibres during repetitive firing of APs. In these experiments, G m was measured using a three‐electrode method that enabled multiple cable parameters and AP waveforms to be determined during the activity (Riisager et al. 2014): three electrodes (V1, V2, V3) were inserted into the same fibre in such a way that it was possible to identify three different inter‐electrode distances (X1–X3, Fig. 1 A). When small‐amplitude currents (−30 nA, 100 ms) were injected through V1 and then through V3, it was possible to record voltage deflections to these currents at the three inter‐electrode distances, and then employ classic cable theory to calculate cable parameters, including G m. Immediately after the small‐amplitude current injected by V3, a train of 10 AP‐trigger pulses was delivered through V1 (30 Hz, 300 nA, 1 ms) (Fig. 1 B). During experiments the current protocols for V1 and V3 (Fig. 1 B) were repeated until 2000 AP‐trigger pulses had been applied. Figure 1 C illustrates membrane potential recordings from V2 and V3 in a representative human abdominal muscle fibre during the first, 100th and 200th run of the current protocols. In these experiments, voltage deflections to the small‐amplitude currents injections were larger at the 100th and 200th application of the current protocols when compared to the first application (Fig. 1 C). This increase in deflection size is most clearly illustrated in the enlarged voltage deflections shown in Fig. 1 D. When the deflections were used for calculation of cable parameters, the increments of the deflections were found to reflect a lowering of G m. The type of experiment illustrated in Fig. 1 A–D was repeated in 18 abdominal muscle fibres and the value of G m in between each AP train was determined. Collectively, these experiments showed that G m was reduced to a stable level after excitation of about 1000 APs (Fig. 1 E, filled circles), and after excitation of 2000 APs, the average G m from these 18 fibres was reduced by 34 ± 9%. Additionally, reduction of G m during AP firing activity was also observed in experiments with human intercostal muscle where triggering of 1600 APs was followed by a reduction of G m by 47 ± 5% (Fig. 1 F). In these fibres, however, a prominent but transient early rise in G m was observed after the first train of APs. To verify that the G m reduction during the repetitive AP firing reflected ClC‐1 regulation, experiments were repeated in the presence of the specific ClC‐1 blocker 9‐AC (Pedersen et al. 2009 b). In these experiments, a small concentration of the Na+ channel inhibitor TTX (10 nm) had to be added to the perfusion solution to avoid myotonic AP firing. At this concentration, TTX completely suppressed myotonia but full‐blown APs could still be triggered. Moreover, control experiments on rat muscles not treated with 9‐AC demonstrated that the addition of 10 nm TTX did not interfere with the excitation‐induced down‐regulation of G m (data not shown). In spite of this, when human abdominal fibres were pre‐treated with both 9‐AC and TTX the G m reduction during AP firing was completely absent, and instead G m was observed rather to slightly increase (Fig. 1 E, open squares).

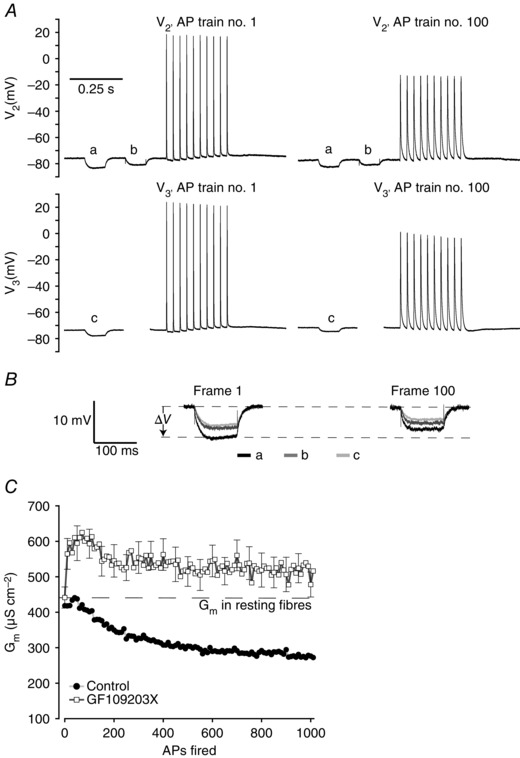

It has previously been demonstrated in rat muscle that ClC‐1 inhibition at the onset of AP firing involves activation of PKC (Pedersen et al. 2009 b). To explore for a similar role of PKC in human abdominal muscle fibres, experiments were next repeated in the presence of 1 μm of the PKC inhibitor GF109203X (Toullec et al. 1991). While GF109203X did not alter the cable parameters in muscle fibres before AP firing activity (Table 1), the recordings in Fig. 2 A and B show that the voltage deflections to the small‐amplitude current injections were actually reduced after the 100th application of the current protocol, indicating an increase in G m. This observation was confirmed in similar experiments on 16 abdominal fibres exposed to GF109203X, where G m on average was increased by 17 ± 6% after 1000 APs had been fired (Fig. 2 C). This clearly contrasted the decreased G m in control fibres and confirms that the ClC‐1 inhibition during AP firing activity indeed depended on PKC activation.

Figure 2. Three‐electrode determination of Gm and recordings of APs in PKC‐inhibited human abdominal muscle fibres .

A, representative recordings of the first (AP 1–10) and 100th (AP 991–1000) AP trains in a human abdominal muscle fibre in the presence of 1 μm PKC inhibitor (GF109203X). B, enlargements of the voltage deflections from the two runs of the current protocols shown in A that were used to determine cable parameters. C, average G m in human abdominal muscle fibres exposed to 1 μm GF109203X during excitation of 1000 APs as illustrated in A (n = 16). The comparable G m measurements from fibres without PKC inhibitor (Fig. 1 E) have been included to indicate the difference between the two experimental conditions. Average data are presented as means ± SEM.

PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition maintains excitability of human muscle fibres during AP firing activity

To explore the physiological role of the PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition during AP firing activity, the effects of PKC inhibition on rheobase current and AP threshold were determined in a subset of abdominal fibres at rest and immediately after firing 1000 APs. Rheobase current was determined by injection of single depolarizing current pulses with increasing strength until an AP was elicited (50 ms, steps of 5 nA starting at 10 nA, Fig. 3 A and B). The AP threshold was determined from the rheobase APs as the membrane voltage at the time point when the first derivative of the AP (dV/dt) exceeded 10 V s−1 (dashed line in Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Illustration of AP threshold determination in human abdominal muscle fibres .

Rheobase current was determined before and immediately after firing 1000 APs (using the protocols illustrated in Fig. 1 B) by injecting 50 ms‐long current pulses that rose progressively from 10 nA in 5 nA steps until an AP was elicited. A, membrane potential recordings from a representative abdominal fibre during rheobase current measurement before and after firing 1000 APs (every second current trace was omitted for clarity). Dashed lines illustrate AP threshold identified as the voltage at which the AP rate of rise exceeded 10 V s−1 (Novak et al. 2015). B, as A but in the presence of 1 μm GF109203X. C and D, first derivative (dV/dt) of the membrane voltage in A and B in which the APs were triggered. The time point when the membrane potential reached AP threshold was identified as the first time point when dV/dt exceeded 10 V s−1 (dashed line).

This analysis showed that compared to the resting condition, the average AP threshold in control fibres was depolarized by around 11 mV (P = 0.013, n = 6 fibres) immediately after the firing of 1000 APs, but despite this, the average rheobase current was lowered by 5 nA after the activity (45 ± 3 and 40 ± 4 nA, respectively, P = 0.332, n = 6 fibres). In contrast, when muscles were pre‐treated with 1 μm of the PKC inhibitor GF109203X the rheobase current was raised by almost 100% after the activity (from 66 ± 6 to 127 ± 11 nA, P = 0.001, n = 6 fibres). This clearly demonstrates that PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition is important for the maintenance of muscle fibre excitability during repeated firing of APs. However, in the experiments with PKC inhibition the rheobase current was assessed in a similar manner as in the control fibres, which means that the 50 ms‐long current injections were increased in steps of 5 nA starting from 10 nA. Due to the lack of PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition during the activity it was necessary to inject many more current steps before an AP was eventually triggered (Fig. 3 B, right panel). The many injections of fairly long‐duration currents most likely caused a progressive inactivation of Na+ channels, and this probably explains why it proved impossible to reliably analyse the AP threshold and AP characteristics from the GF109203X‐treated fibres after AP firing activity in these experiments.

To still explore whether the PKC inhibitor affected the AP characteristics, an analysis of the APs in the AP trains was performed. This approach was chosen because the APs in the trains were triggered by supra‐threshold current injections and this avoided the accumulating inactivation of Na+ channels imposed during the rheobase protocol. Table 2 summarizes the results from this analysis. Compared to the first AP in the first train (AP no. 1), AP no. 1000 was broader and had a lowered rate of rise both in the control and GF109203X‐treated fibres. No significant difference of AP no. 1 or AP no. 1000 was observed when comparing the AP characteristics between control and GF109203X‐treated fibres.

Table 2.

Effect of AP firing and PKC inhibition on AP characteristics from human abdominal muscle fibres

| Treatment | n | AP amplitude (mV) | AP rate of rise (V s−1) | AP half‐height width (ms) | G m (μS cm−2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP no. 1 | — | 18 | 89 ± 3 | 304 ± 24 | 1.14 ± 0.03 | 418 ± 19 |

| AP no. 1000 | — | 18 | 80 ± 3 | 195 ± 27 | 2.37 ± 0.15 | 267 ± 16 |

| P value | — | — | 0.00371 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| AP no. 1 | 1 μm GF | 16 | 88 ± 4 | 284 ± 34 | 1.32 ± 0.12 | 441 ± 30 |

| AP no. 1000 | 1 μm GF | 16 | 74 ± 4 | 158 ± 25 | 2.85 ± 0.3 | 516 ± 51 |

| P value | — | — | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0027 |

AP characteristics of AP no. 1 and AP no. 1000 excited in the human abdominal fibres. Values were determined using data from V3 during the recordings of G m and APs with the three‐electrode method. GF, PKC inhibitor GF109203X. Average values are presented as means ± SEM. A paired t test was used to test for significant differences between AP nos 1 and 1000. n represents the number of fibres.

PKC phosphorylation changes the open probability of ClC‐1 channels

To study the PKC‐dependent regulation of ClC‐1 channels in greater detail we heterologously expressed wild‐type human ClC‐1 in Xenopus oocytes. ClC‐1 function was examined by applying voltage protocol A (Fig. 4 A) at different time points, either during control experiments (Fig. 4 B–D, top panels), or after activation of PKC by 200 nm PMA (Fig. 4 B–D, middle panels). Figure 4 B shows recorded whole cell current traces elicited by the voltage protocol at the indicated conditions before and 10 min after solution exchange. For the two time points, the normalized values of the initial tail current, which represents P o, were then plotted as a function of the preceding test voltage (Fig. 4 C). The results from these experiments showed that under control conditions, the 10 min of incubation in control ND96 solution led to a small left shift in the half‐maximum activation voltage (V 1/2) from −79 ± 4 to −86 ± 5 mV (Fig. 4 C, top panel). In contrast, when PMA was added at time zero to activate PKC it led to a significant right shift in V 1/2 from −81 ± 4 mV to −29 ± 3 mV (Fig. 4 C, middle panel). This right shift could be almost completely prevented by pre‐incubating the ClC‐1‐expressing oocytes for 1 h with 1 μm GF109203X. In these oocytes, V 1/2 was changed from −82 ± 6 mV before addition of PMA to −76 ± 9 mV after 10 min of PMA exposure (Fig. 4 B–D, lower panels). In an additional control experiment an inactive analogue of PMA (1 μm of 4αPDD) did not change the activation voltage of the expressed ClC‐1 (data not shown). This confirmed that the PMA‐mediated effect is related to a specific activation of PKC.

In order to compare the results of PKC activation on ClC‐1 function in oocytes to the results obtained from human skeletal muscle fibres, Fig. 4 D also shows how the tail currents at a test voltage of −80 mV and 60 mV developed during the 10 min of incubation. These test voltages were chosen because they are close to the resting membrane potential and the membrane potential at the peak of the APs in the human abdominal muscle fibres, respectively. This analysis showed that the initial tail current following the 60 mV test voltage did not change when PKC was activated in the oocytes. In contrast, the current following the −80 mV test voltage was decreased by 59 ± 3% 10 min after addition of PMA (compare Fig. 4 D top and middle panels).

Effect of PKC activation on ClC‐1 fast and slow gating

In the final series of experiments, we analysed how the fast and the slow gates of ClC‐1 were affected by PKC activation. In order to separate the open probabilities of the fast and slow gates (P o f and P o s) we used the method described by Accardi and Pusch (2000), which takes advantage of the different kinetics of the gating mechanisms at very positive voltages. This was done using voltage protocols A and B (Fig. 5 A) in a subset of ClC‐1‐expressing oocytes. Results from these experiments are illustrated in the three panels of Fig. 5 B. They show how P o, P o s and P o f were altered in response to activation of PKC by 10 min exposure to 200 nm PMA. When comparing changes to P o s and P o f and taking into account both the changes in V 1/2 and the minimal open probability (P min) it is clear that the P o s was most pronouncedly affected by the PKC activation. Thus, as summarized in Table 3 the V 1/2 of P o s was right‐shifted by around 38 mV (P < 0.000001, n = 9 oocytes) while P min was reduced by around 26% (P < 0.00001, n = 9 oocytes) (Fig. 5 B, middle panel). This should be compared to a 20 mV right shift in V 1/2 of P o f (P < 0.00001, n = 9 oocytes) (Fig. 5 B, bottom panel). These results prompted a series of experiments using the C277S ClC‐1 mutant in which regulation of the fast gate is maintained while the slow gating is effectively locked open (Accardi et al. 2001). The results of this last series of experiments showed that the C277S mutation almost completely removed the effect of PKC activation (Fig. 5 C and Table 3). This suggests that the effect of PKC activation on ClC‐1 is predominantly mediated by the slow gate and that fast gate modulation by PKC depends on a functional slow gate.

Table 3.

Gating parameters for WT and mutant human ClC‐1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes

| Oocyte | P o V 1/2 (mV) | P o V 1/2 (mV) | P o f V 1/2 (mV) | P o f V 1/2 (mV) | P o s V 1/2 (mV) | P o s V 1/2 (mV) | P o s residual | P o s residual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treatment | 0 min | 10 min | 0 min | 10 min | 0 min | 10 min | (%) 0 min | (%) 10 min |

| Control (WT, n = 6) | −68 ± 4 | −76 ± 5* | −98 ± 3 | −104 ± 3 | −44 ± 6 | −42 ± 7 | 52 ± 4 | 55 ± 5* |

| P value | — | 0.001 | — | 0.102 | — | 0.499 | — | 0.025 |

| 200 nm PMA (WT, n = 9) | −83 ± 5 | −31 ± 5* | −110 ± 4 | −88 ± 4* | −44 ± 2 | −6 ± 2* | 59 ± 4 | 33 ± 2* |

| P value | — | <0.0001 | — | <0.0001 | — | <0.0001 | — | <0.0001 |

| 200 nm PMA (C277S, n = 9) | −74 ± 4 | −68 ± 4* | −83 ± 4 | −79 ± 3 | −37 ± 4 | −41 ± 2 | 81 ± 3 | 75 ± 3* |

| P value | — | 0.032 | — | 0.116 | — | 0.372 | — | 0.010 |

n represents number of oocytes and values are presented as means ± SEM. *Values significantly different from 0 min under the same conditions.

Discussion

ClC‐1 channel regulation during activity in human skeletal muscle

This study explored whether regulation of ClC‐1 channels occurs in human skeletal muscle fibres during activity as it has been established in muscles from rodents (Pedersen et al. 2009 a,b; Riisager et al. 2014). We employed electrophysiological methods with two or three intracellular electrodes in order to induce AP‐firing activity in the fibres and at the same time measure G m with a time resolution that is high enough to determine changes on a time scale of seconds (Riisager et al. 2014). The main findings were that AP‐firing activity in fibres from human abdominal and intercostal muscle was followed by a ClC‐1‐mediated down‐regulation of G m resembling the earlier findings in rodents. This demonstrates that activity‐mediated down‐regulation of chloride conductance (G Cl) is a common feature in human muscle and various mammalian species. Thus, our experiments showed that the average G m was reduced by 34 ± 9% (n = 18 fibres) and 47 ± 5% (n = 8 fibres) after reaching a stable level in AP firing in fibres from abdominal and intercostal muscles, respectively. This reduction is comparable to findings in rat and mouse soleus fibres where similar intensity and duration of AP firing activity induced a 61 ± 9% down‐regulation of G m (Pedersen et al. 2009 a). Repeating the experiments in human abdominal fibres exposed to saturating concentrations of the ClC‐1 inhibitor 9‐AC made it possible to estimate the average change in G Cl during the activity by subtracting the resulting 9‐AC‐insensitive G m from control measurements. From these data it is estimated that G Cl was reduced by 54 ± 2% in human abdominal muscle, which is almost equivalent to the reduction in rat fibres (Pedersen et al. 2009 a). The close correspondence between observations in rat and human muscles suggests that the PKC‐dependent signal transduction pathway involved in ClC‐1 inhibition may be initiated by AP‐mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release during activity, also in human skeletal muscle (Pedersen et al. 2009 b). Collectively, these observations show that onset of activity in human skeletal muscle triggers a pronounced reduction in G Cl that reflects underlying inhibition of ClC‐1 channels, and that it is comparable to reductions observed in active rat muscle.

The regulation of ClC‐1 is dependent on activation of PKC

Experiments conducted with the PKC inhibitor present clearly demonstrate that PKC activation was important for ClC‐1 regulation during AP firing. Thus, in contrast to the control situation, these experiments showed that G m was increased after firing 1000 APs. Furthermore, the results showed that incubation with 1 μm GF109203X did not change G m in abdominal muscle fibres before AP firing activity when compared to control fibres. This finding could suggest that at least in these human skeletal muscle fibres ClC‐1 channels are not inhibited by PKC at rest. However, in contrast to the control situation PKC‐inhibited fibres underwent a significant rise in G m already after firing one train of APs. In the intercostal fibres a similar rise was observed even in the control fibres but this rise was transient. It could be speculated that this rise in G m at the very beginning of AP firing could be due to a voltage‐dependent activation of the ClC‐1 channels as it was sensitive to 9‐AC in abdominal muscle. This voltage‐dependent ClC‐1 activation could lead to higher open probability during trains of APs, but the current data do not allow further clarification of this hypothesis.

The PKC‐dependent regulation of ClC‐1 maintains the excitability of active human skeletal muscle

To investigate whether the effect of ClC‐1 regulation during activity had any effect on the excitability of human skeletal muscle we analysed the rheobase current and AP threshold in a subset of fibres at rest and immediately after firing 1000 APs, both with and without PKC inhibition. This analysis showed that the average AP threshold in control fibres was elevated by around 11 mV (P = 0.013, n = 6 fibres) after firing 1000 APs. Despite this, the rheobase current did not change significantly (P = 0.33, n = 6 fibres) but had, contrastingly, a tendency to be lowered. This showed that the excitability of the fibres was well maintained after the AP firing. Repetitive firing of APs is known to be associated with an increase in extracellular K+ that has been suggested to threaten the excitability of the active muscle fibre because it can induce increased inactivation of voltage‐gated Na+ channels (for review see Sejersted & Sjøgaard, 2000). In this context, the well‐maintained excitability of the fibres after repetitive AP firing could indicate that the PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 inhibition is an important mechanism for protecting the fibre excitability when fibres are facing extended Na+ channel inactivation. This notion was further supported by the results from PKC‐inhibited fibres showing a close to 100% increase in rheobase current after the activity. Unfortunately the high rheobase current meant that many current steps with progressively increasing amplitude had to be injected to trigger an AP. This was likely to have caused progressive inactivation of Na+ channels, which resulted in sluggish APs with low peak when finally excited. For this reason it was not possible to reliably analyse the AP threshold and AP characteristics of the GF109203X‐treated fibres after the AP firing activity. Instead, AP characteristics were determined from APs from the first (AP no. 1) and the last train (AP no. 1000), which were triggered by supra‐threshold current injections. When compared to AP no. 1, AP no. 1000 was broader and had a lower rate of rise in both control and GF109203X‐treated fibres. There were, however, no significant differences between the control and PKC‐inhibited fibres at AP no. 1 or AP no. 1000 (Table 2).

PKC activation changes the open probability of human ClC‐1 expressed in oocytes

To further understand the mechanism behind PKC‐dependent ClC‐1 regulation, we next investigated how activation of PKC changed the voltage sensitivity of human ClC‐1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. This set of experiments demonstrated that the effect of 10 min of PKC activation by PMA resulted in a significant shift of the overall open probability of the channel towards depolarized potentials, an effect that could be almost completely blocked by GF109203X. While the channel P o was shifted the maximal current amplitude measured at the most positive test voltage was not changed during the first 10 min after addition of the PKC activator. On the other hand, our experiments showed that at a test voltage of −80 mV, which is comparable to the resting membrane potential of the human abdominal muscle fibres, the relative current amplitude was reduced by 59%, compared to before PKC activation. This finding shows that the reduction in G m during repetitive AP firing can be explained by PKC causing a depolarizing shift in the open probability of ClC‐1.

Effect of PKC activation on the slow and fast gate of human ClC‐1

Since the effect of PKC activation was shown to right shift the overall open probability of the ClC‐1 channels, we further examined the effect to deduce how it altered the voltage dependence of the individual slow and fast gating mechanisms. These results showed that PKC activation with PMA affected both gates although the largest effect appeared to be on the slow gate. Thus, the PKC‐dependent phosphorylation asserts its effect on ClC‐1 by shifting the P o s activation curve to the right by around 38 mV and simultaneously reducing the P o s minimal open probability by 26%. In addition to this, PKC activation caused the P o f activation curve to shift to the right by around 20 mV. When experiments were repeated with the C277S mutation, which has been shown to lock the slow gate in an open state while leaving the fast gate intact (Accardi et al. 2001), the effect of PKC activation was almost completely removed. This suggests that the effect of PKC activation on ClC‐1 gating is predominantly mediated by the slow gate and it also suggests that fast gate modulation by PKC depends on a functional slow gate.

Hsiao et al. (2010) have also reported that the ClC‐1 activation curve was shifted to the right when exposed to phorbol esters. Although they did not explore whether the effect is caused by changes in P o f or P o s, they did locate a PKC phosphorylation site on human ClC‐1 in the C‐terminal domain (residue 891–893) of the channel. Mutating one serine residue in this potential PKC phosphorylation site was shown to shift the ClC‐1 activation curve to the right (Hsiao et al. 2010) and simultaneously abolish the effect of phorbol esters. Interestingly, the right shifts of the activation curve of ClC‐1 caused by this serine mutation as well as by PKC modulation appear to be similar to those observed in two ClC‐1 mutants with C‐terminus truncations at the nearby region of the potential PKC phosphorylation site (K875X and R894X) (Hebeisen & Fahlke, 2005). These results are consistent with other studies showing that interactions between the cytoplasmic C‐terminal domain and the membrane resident pore region of the channel result in altered slow gating (Estévez et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2006; Bykova et al. 2006; Ma et al. 2011; Bennetts & Parker, 2013). On the other hand, Rosenbohm et al. (1999) reported that the application of phorbol ester did not affect the gating but changed the ion permeation through the pore of ClC channels expressed in mammalian cell lines. The reasons underlying the apparent discrepancy between the conclusion by Rosenbohm et al. (1999) and the results reported here and by Hsiao et al. (2010) are not clear at this moment. It is possible that different channel expression systems and recording techniques could cause the apparent discrepancy.

Our observation that the activation curve of ClC‐1 was shifted to the right by the phorbol ester‐induced PKC activation reproduced what was reported by Hsiao et al. (2010). Furthermore, the little effect of PKC activation on the C277S mutant is consistent with PKC predominantly affecting PKC gating rather than permeation. We therefore hypothesize that the effect of PKC phosphorylation results in a structural modification of the C‐terminal part of the two subunits that modulates their interaction with the channel pore region and thereby alters slow gating. In support of this hypothesis, similar phosphorylation‐induced conformational changes result in altered slow gating in the CLH‐3b channel, a member of the ClC anion channel family expressed in Caenorhabditis elegans (Yamada et al. 2013).

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, the present study is the first demonstration of ClC‐1 regulation in active human muscle. It provides a detailed description of the involvement of PKC and ClC‐1 in the down‐regulation of G m during AP‐firing activity in human skeletal muscle fibres. This regulation represents a mechanism by which working muscle fibres maintain their excitability which is important for upholding muscle function during physical activity in humans. Also, the present results give insight into how the PKC‐dependent phosphorylation of ClC‐1 channels changes the voltage‐dependent open probability of the channels through alterations of mostly the slow but also the fast gating of the channel.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and/or design of the experiments. A.R., F.V. d.P. and T.H.P. performed the experiments on human skeletal muscle and they collected and analysed the data. A.R. and W.‐P.Y. performed the experiments on oocytes and they collected and analysed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data. The article manuscript was drafted by A.R., O.B.N. and T.H.P., and was revised critically for important content by W.‐P.Y., T.‐Y.C. and F.V.d.P. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed. Experiments on human skeletal muscle were performed at the Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University. Experiments on oocytes were performed at the Centre for Neuroscience, University of California, Davis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Health Science, Aarhus University (A.R.), the Danish Medical Research Council (O.B.N.), the Novo Nordic Foundation (13143) (T.H.P.) and the National Institutes of Health (USA, R01GM065447) (T.‐Y.C.).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yawei Yu for help with oocyte recordings (University of California, Davis). Additionally, we thank M. Stürup‐Johansen and V. Uhre for skilled technical assistance (University of Aarhus).

References

- Accardi A, Ferrera L & Pusch M (2001). Drastic reduction of the slow gate of human muscle chloride channel (ClC‐1) by mutation C277S. J Physiol 534, 745–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accardi A & Pusch M (2000). Fast and slow gating relaxations in the muscle chloride channel CLC‐1. J Gen Physiol 116, 433–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetts B & Parker MW (2013). Molecular determinants of common gating of a ClC chloride channel. Nat Commun 4, 2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetts B, Rychkov GY, Ng H‐L, Morton CJ, Stapleton D, Parker MW & Cromer BA (2005). Cytoplasmic ATP‐sensing domains regulate gating of skeletal muscle ClC‐1 chloride channels. J Biol Chem 280, 32452–32458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmeier H & Jockusch H (1987). Activators of protein kinase C induce myotonia by lowering chloride conductance in muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 148, 1383–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant SH & Conte‐Camerino D (1991). Chloride channel regulation in the skeletal muscle of normal and myotonic goats. Pflugers Arch 417, 605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant SH & Morales‐Aguilera A (1971). Chloride conductance in normal and myotonic muscle fibres and the action of monocarboxylic aromatic acids. J Physiol 219, 367–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykova EA, Zhang X‐D, Chen T‐Y & Zheng J (2006). Large movement in the C terminus of CLC‐0 chloride channel during slow gating. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13, 1115–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MF & Jockusch H (1999). Role of phosphorylation and physiological state in the regulation of the muscular chloride channel ClC‐1: a voltage‐clamp study on isolated M. interosseus fibers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 261, 528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzoli A, Liantonio A, Conte E, Cannone M, Massari AM, Giustino A, Scaramuzzi A, Pierno S, Mantuano P, Capogrosso RF, Camerino GM & De Luca A (2014). Angiotensin II modulates mouse skeletal muscle resting conductance to chloride and potassium ions and calcium homeostasis via the AT1 receptor and NADPH oxidase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307, C634–C647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paoli FV, Broch‐Lips M, Pedersen TH & Nielsen OB (2013). Relationship between membrane Cl− conductance and contractile endurance in isolated rat muscles. J Physiol 591, 531–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffield M, Rychkov G, Bretag A & Roberts M (2003). Involvement of helices at the dimer interface in ClC‐1 common gating. J Gen Physiol 121, 149–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT & MacKinnon R (2002). X‐ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 Å reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature 415, 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estévez R, Pusch M, Ferrer‐Costa C, Orozco M & Jentsch TJ (2004). Functional and structural conservation of CBS domains from CLC chloride channels. J Physiol 557, 363–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Campbell EB, Hsiung Y & MacKinnon R (2010). Structure of a eukaryotic CLC transporter defines an intermediate state in the transport cycle. Science 330, 635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink R & Lüttgau HC (1976). An evaluation of the membrane constants and the potassium conductance in metabolically exhausted muscle fibres. J Physiol 263, 215–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebeisen S & Fahlke C (2005). Carboxy‐terminal truncations modify the outer pore vestibule of muscle chloride channels. Biophys J 89, 1710–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL & Nakajima S (1972). The effect of diameter on the electrical constants of frog skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 221, 105–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL & Rushton WA (1946). The electrical constants of a crustacean nerve fibre. Proc R Soc Med 134, 444–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao KM, Huang RY, Tang PH & Lin MJ (2010). Functional study of CLC‐1 mutants expressed in Xenopus oocytes reveals that a C‐terminal region Thr891‐Ser892‐Thr893 is responsible for the effects of protein kinase C activator. Cell Physiol Biochem 25, 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack JB, Noble D & Tsien R (1975). Electric Current Flow in Excitable Cells. Clarendon Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ (2008). CLC chloride channels and transporters: from genes to protein structure, pathology and physiology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 43, 3–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch MC, Steinmeyer K, Lorenz C, Ricker K, Wolf F, Otto M, Zoll B, Lehmann‐Horn F, Grzeschik KH & Jentsch TJ (1992). The skeletal muscle chloride channel in dominant and recessive human myotonia. Science 257, 797–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwieciński H, Lehmann‐Horn F & Rüdel R (1984). The resting membrane parameters of human intercostal muscle at low, normal, and high extracellular potassium. Muscle Nerve 7, 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipicky RJ (1979). Myotonic syndromes other than myotonic dystrophy In Handbook of Clinical Neurology, vol. 40, ed. Vinken PJ & Bruyn GW, pp. 533–571. Elsevier, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Lipicky RJ, Bryant SH & Salmon JH (1971). Cable parameters, sodium, potassium, chloride, and water content, and potassium efflux in isolated external intercostal muscle of normal volunteers and patients with myotonia congenita. J Clin Invest 50, 2091–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Rychkov GY, Bykova EA, Zheng J & Bretag AH (2011). Movement of hClC‐1 C‐termini during common gating and limits on their cytoplasmic location. Biochem J 436, 415–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComas AJ & Mrozek K (1968). The electrical properties of muscle fibre membranes in dystrophia myotonica and myotonia congenita. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 31, 441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C (2006). ClC chloride channels viewed through a transporter lens. Nature 440, 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak KR, Norman J, Mitchell JR, Pinter MJ & Rich MM (2015). Sodium channel slow inactivation as a therapeutic target for myotonia congenita. Ann Neurol 77, 320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade PT & Barchi RL (1977). Characteristics of the chloride conductance in muscle fibres of the rat diaphragm. J Gen Physiol 69, 325–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen TH, de Paoli F & Nielsen OB (2005). Increased excitability of acidified skeletal muscle: role of chloride conductance. J Gen Physiol 125, 237–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen TH, de Paoli FV, Flatman JA & Nielsen OB (2009. a). Regulation of ClC‐1 and KATP channels in action potential‐firing fast‐twitch muscle fibres. J Gen Physiol 134, 309–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen TH, Macdonald WA, de Paoli FV, Gurung IS & Nielsen OB (2009. b). Comparison of regulated passive membrane conductance in action potential‐firing fast‐ and slow‐twitch muscle. J Gen Physiol 134, 323–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierno S, Camerino GM, Cippone V, Rolland J‐F, Desaphy J‐F, De Luca A, Liantonio A, Bianco G, Kunic JD, George AL Jr & Conte Camerino D (2009). Statins and fenofibrate affect skeletal muscle chloride conductance in rats by differently impairing ClC‐1 channel regulation and expression. Br J Pharmacol 156, 1206–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierno S, De Luca A, Desaphy J‐F, Fraysse B, Liantonio A, Didonna MP, Lograno M, Cocchi D, Smith RG & Camerino DC (2003). Growth hormone secretagogues modulate the electrical and contractile properties of rat skeletal muscle through a ghrelin‐specific receptor. Br J Pharmacol 139, 575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M (2002). Myotonia caused by mutations in the muscle chloride channel gene CLCN1 . Hum Mutat 19, 423–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riisager A, Duehmke R, Nielsen OB, Huang CL & Pedersen TH (2014). Determination of cable parameters in skeletal muscle fibres during repetitive firing of action potentials. J Physiol 592, 4417–4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbohm A, Rüdel R & Fahlke C (1999). Regulation of the human skeletal muscle chloride channel hClC‐1 by protein kinase C. J Physiol 514, 677–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saviane C, Conti F & Pusch M (1999). The muscle chloride channel ClC‐1 has a double‐barreled appearance that is differentially affected in dominant and recessive myotonia. J Gen Physiol 113, 457–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sejersted OM & Sjøgaard G (2000). Dynamics and consequences of potassium shifts in skeletal muscle and heart during exercise. Physiol Rev 80, 1411–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skov M, De Paoli FV, Lausten J, Nielsen OB & Pedersen TH (2015). Extracellular magnesium and calcium reduce myotonia in isolated ClC‐1 chloride channel‐inhibited human muscle. Muscle Nerve 51, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmeyer K, Ortland C & Jentsch T (1991). Primary structure and functional expression of a developmentally regulated skeletal muscle chloride channel. Nature 354, 301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand‐Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E & Loriolle F (1991). The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem 266, 15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricarico D, Conte Camerino D, Govoni S & Bryant SH (1991). Modulation of rat skeletal muscle chloride channels by activators and inhibitors of protein kinase C. Pflugers Arch 418, 500–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng P‐Y, Bennetts B & Chen T‐Y (2007). Cytoplasmic ATP inhibition of CLC‐1 is enhanced by low pH. J Gen Physiol 130, 217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Rychkov GY, Hughes BP & Bretag AH (2006). Functional complementation of truncated human skeletal‐muscle chloride channel (hClC‐1) using carboxyl tail fragments. Biochem J 395, 89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Bhate MP & Strange K (2013). Regulatory phosphorylation induces extracellular conformational changes in a CLC anion channel. Biophys J 104, 1893–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]