Abstract

Key points

Two functional abnormalities of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a 25% reduction of the single‐channel conductance (g) and a ∼13‐fold lower open probability (P o), were found with the R117H mutation that is associated with mild forms of cystic fibrosis.

Characterizations of the gating defects of R117H‐CFTR led to the conclusion that the mutation decreases P o by perturbing the gating conformational changes in CFTR's transmembrane domains (TMDs) without altering the function of the nucleotide binding domains (NBDs).

Nonetheless, gating of the R117H‐CFTR can be improved by a variety of pharmacological reagents supposedly acting on NBDs such as ATP analogues, or TMDs (e.g. VX‐770 or nitrate). These reagents potentiate synergistically R117H‐CFTR gating to a level that allows accurate assessments of its gating deficits.

Our studies not only elucidate the mechanism underpinning gating dysfunction of R117H‐CFTR, but also provide a mechanistic understanding of how VX‐770 ameliorates the gating defects in the R117H mutant.

Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by loss‐of‐function mutations of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene encoding a phosphorylation‐activated, but ATP‐gated chloride channel. In the current study, we investigated the mechanism responsible for the gating defects manifested in R117H‐CFTR, an arginine‐to‐histidine substitution at position 117 of CFTR that is associated with mild forms of CF. We confirmed previous findings of a 25% decrease of the single‐channel conductance (g) in R117H‐CFTR, but found a ∼13‐fold lower open probability (P o). This dramatic gating deficit is not due to dysfunctional nucleotide binding domains (NBDs) as the mutation does not alter the apparent affinity for ATP, and the mutant channels respond to ATP analogues in a similar manner as wild‐type CFTR. Furthermore, once ATP hydrolysis is abolished, the R117H mutant can be trapped in a prolonged ‘burst opening’ conformation that is proposed to be equipped with a stable NBD dimer. On the other hand, our results support the conclusion that the R117H mutation decreases P o by perturbing the gating conformational changes in CFTR's transmembrane domains as even when NBDs are kept at a dimerized configuration, P o is reduced by ∼10‐fold. Moreover, our data demonstrate that a synergistic improvement of R117H‐CFTR function can be accomplished with a combined regiment of VX‐770 (Ivacaftor), nitrate ion (NO3 −) and N 6‐(2‐phenylethyl)‐2′‐deoxy‐ATP (d‐PATP), which almost completely rectifies the gating defect of R117H‐CFTR. Clinical implications of our results are discussed.

Key points

Two functional abnormalities of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a 25% reduction of the single‐channel conductance (g) and a ∼13‐fold lower open probability (P o), were found with the R117H mutation that is associated with mild forms of cystic fibrosis.

Characterizations of the gating defects of R117H‐CFTR led to the conclusion that the mutation decreases P o by perturbing the gating conformational changes in CFTR's transmembrane domains (TMDs) without altering the function of the nucleotide binding domains (NBDs).

Nonetheless, gating of the R117H‐CFTR can be improved by a variety of pharmacological reagents supposedly acting on NBDs such as ATP analogues, or TMDs (e.g. VX‐770 or nitrate). These reagents potentiate synergistically R117H‐CFTR gating to a level that allows accurate assessments of its gating deficits.

Our studies not only elucidate the mechanism underpinning gating dysfunction of R117H‐CFTR, but also provide a mechanistic understanding of how VX‐770 ameliorates the gating defects in the R117H mutant.

Abbreviations

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- ECL1

first extracellular loop

- i

single‐channel current amplitude

- g

single channel conductance

- TMDs

transmembrane domains

- NBDs

nucleotide‐binding domains

- Po

open probability

- PKA

protein kinase A

- τo

mean open (burst) time

- τc

mean closed (interburst) time

- N

number of channels in the cell membrane

- r

rate constant

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF), the most prevalent life‐shortening genetic disorder in Caucasians (Riordan et al. 1989; Welsh & Smith, 1993), is caused by defective transepithelial salt and water transport due to mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that encodes an ATP‐gated anion channel (Gadsby et al. 2006). Although the high‐resolution structure of the whole CFTR protein has not been resolved (Rosenberg et al. 2004; Mio et al. 2008), the overall architecture of the CFTR protein can be divided into three major components based on their functional roles: a gated chloride permeation pathway (or pore) transporting anions constructed by the transmembrane domains (TMDs) (Bai et al. 2010; El Hiani & Linsdell, 2010), cytosolic gating machinery known as the nucleotide‐binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) where ATP binding and hydrolysis control the opening and closing of the gate (Gadsby et al. 2006; Jih & Hwang, 2012), and a regulatory (R) domain containing multiple consensus serine/threonine residues, phosphorylation of which by protein kinase A (PKA) is a prerequisite for the action of ATP (Gadsby & Nairn, 1999; Seibert et al. 1999). Normal operation of the CFTR channel and hence the CFTR‐mediated transepithelial anion transport plays a critical role in ion–fluid homeostasis across a variety of epithelia, including airways, reproductive tract, pancreas, intestine and sweat duct (Quinton, 1990). Therefore, patients with CF manifest symptoms reflecting multi‐organ dysfunction (Robertson et al. 2006).

So far, more than 2000 mutations in the CFTR gene have been linked to CF (www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/cftr). These mutations can be categorized into six classes by the types of cellular/molecular defects introduced (Welsh & Smith, 1993; Zielenski & Tsui, 1995; Haardt et al. 1999): impairment at the transcription/translation level (Class I), defective intracellular processing of the CFTR protein (Class II; e.g. F508del), gating abnormalities (Class III; e.g. G551D), diminished chloride conductance (Class IV; e.g. R117H), reduced CFTR transcription and synthesis (Class V), and decreased cell surface stability (Class VI). Generally speaking, mutations belonging to Classes I, II and III cause a more severe form of CF, whereas Class IV, V and VI mutations are associated with a milder phenotype. While this classification has been used for years and many mutations can be unambiguously categorized into certain classes, pinning a particular mutant into one single class can be problematic and imprecise in some cases. Take F508del‐CFTR as an example. This most common pathogenic mutation has been considered as a prototype for Class II mutations because the deletion of F508 results in protein folding defects, the consequence of which is retention of the mutant proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (Cheng et al. 1990; Denning et al. 1992; Lazrak et al. 2013). However, those F508del‐CFTR channels that escape trapping in the endoplasmic reticulum exhibit salient gating defects once they reach the plasma membrane (Dalemans et al. 1991), as well as an increased protein turnover (Lukacs et al. 1993). Multi‐faceted defects also occur in other pathogenic mutations such as R117H, which was conventionally sorted as a Class IV mutation, but previous studies also suggested gating anomalies (Sheppard et al. 1993; Zhou et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2014). Proper categorization of pathogenic mutations offers guidance for the development of therapeutics and the prognosis in CF. For example, drugs that help CFTR trafficking [i.e. correctors, e.g. VX‐809 (Van Goor et al. 2011)] target Class II mutations, whereas reagents that improve CFTR gating [i.e. potentiators, e.g. VX‐770 (Van Goor et al. 2009; Jih & Hwang, 2013)] are developed for Class III mutations. However, in practice, a combined regiment of correctors and potentiators is needed to overcome both trafficking and gating defects manifested in F508del‐CFTR (Wainwright et al. 2015; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01225211 and NCT01531673). Recent successes in clinical trials have established precedents for the application of this mutation classification‐targeted therapeutic strategy not only to patients carrying severe‐form mutations (e.g. G551D; Ramsey et al. 2011), but also those with mild‐form mutations such as R117H (Moss et al. 2015).

Arginine 117 is located in the first extracellular loop (ECL1) between the first and second transmembrane segments. Sheppard et al. (1993) were the first to report that the disease‐associated mutation R117H reduces the single‐channel conductance. In the same report, they also showed an open probability (P o) that is less than one‐third of that of the wild‐type with characteristic brief open time. Several follow‐up studies echoed these findings: a reduced conductance and flickering openings with R117H‐CFTR expressed in baby hamster kidney cells (Zhou et al. 2008) or Xenopus oocytes (Cui et al. 2014). Furthermore, Price et al. (1996) proposed that the charged residues including R117 in the ECL1 of Xenopus CFTR are involved in regulating CFTR channel gating. However, Hӓmmerle et al. (2001) reported that reconstituted R117H‐CFTR in lipid bilayers exhibits reduced single‐channel conductance without apparent gating abnormalities. This latter study raises an interesting puzzle of how a minute reduction of the single‐channel conductance without other functional/biochemical defects can account for the disease phenotype of an increased [Cl−]sweat (Wilschanski et al. 1995). While resolving this discrepancy is important, what is more interesting is to answer if and how a mutation at ECL1 can profoundly affect gating, which is thought to be controlled mainly by CFTR's NBDs (Gadsby et al. 2006). Indeed, Cui et al. (2014) suggest an abnormal function of NBDs associated with mutations at this very position.

In the current study, we first confirmed those observations reported by Sheppard et al. (1993): reduced single‐channel conductance and P o with R117H‐CFTR. However, we provided experimental evidence that the defective gating mechanism of R117H‐CFTR is unlikely to be caused by malfunctioned NBDs. Our data are more in line with the conclusion that the R117H mutation decreases P o by perturbing opening/closing of the gate in CFTR's TMDs with little alteration in NBD function. To more quantitatively assess R117H‐associated gating defects, we tested the effects of various pharmacological reagents that may target different domains of CFTR and hence affect different kinetic steps in CFTR gating. Indeed, our data show that VX‐770 (Van Goor et al. 2009; Jih & Hwang, 2013), ATP analogues (Miki et al. 2010) and nitrate (Yeh et al. 2015) exert complementary actions on R117H‐CFTR: the P o of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of all three reagents approaches that of WT channels. The clinical implications of our results for genotype–phenotype relationships in CF will be discussed.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. For transient expression of CFTR, cells were pre‐seeded into 35 mm tissue culture dishes 1 day before transfection. The CHO cells were then co‐transfected with CFTR‐cDNA (pcDNA 3.1 Zeo (+) vector; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and pEGFP‐C3 (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) using PolyFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. After transfection, cells were harvested and re‐seeded onto glass chips, and incubated at 27 ºC for at least 2 days before electrophysiological experiments were performed.

Mutagenesis

The R117H mutation was introduced into WT‐CFTR and E1371Q‐CFTR backgrounds with QuikChange XL kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the nucleotide sequences of the resulting mutants were verified by DNA sequencing (DNA core, University of Missouri).

Electrophysiological recordings

Glass chips carrying the transfected cells were transferred to a chamber located on the stage of an inverted microscope (IX50; Olympus, Tokyo, Japa). Patch‐clamp electrodes were made from borosilicate glass capillaries (Kimble & Chase, Vineland, NJ, USA) using a two‐step vertical micropipette puller (PP‐81, Narishige, Japan). The pipettes were polished with a homemade microforge to a resistance of 2 – 4 MΩ in the bath solution. Once the seal resistance reached > 40 GΩ, membrane patches were excised into an inside‐out mode. Subsequently, the pipette was moved to the outlet of a three‐barrel perfusion system and perfused with 25 IU PKA and 2 mM ATP until the CFTR current reached a steady state. Approximately 6 IU PKA was added to other ATP‐containing solutions to maintain the phosphorylation level as described previously (Jih & Hwang, 2013; Yeh et al. 2015). The membrane potential (V m) was held at −50 mV during recording unless noted otherwise. All solution changes were performed with a fast solution change system (SF‐77B; Warner Instruments, LLC, Hamden, CT, USA) with a dead‐time of ∼30 ms (Tsai et al. 2009).

CFTR currents were recorded at room temperature with a patch‐clamp amplifier (EPC9, HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany). Data were filtered online at 100 Hz with an eight‐pole Bessel filter (LPF‐8; Warner Instruments) and digitized to a computer at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. For recordings in excised inside‐out patches, we used a pipette solution containing (in mM): 140 N‐methyl‐D‐glucamine chloride (NMDG‐Cl), 5 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2 and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NMDG). Before patch excision, cells were perfused with a bath solution containing (in mM): 145 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 5 glucose, 5 HEPES and 20 sucrose (pH 7.4 with NaOH). After patch excision, the pipette was bathed in a perfusion solution containing (in mM): 150 NMDG‐Cl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 EGTA and 8 Tris (pH 7.4 with NMDG). For nitrate (NO3 −) experiments, NMDG‐Cl in the inside‐out perfusion was replaced with NMDG‐NO3.

Chemicals and solution compositions

Mg‐ATP, 2′‐deoxy‐ATP (d‐ATP), PPi (pyrophosphate) and PKA were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. N 6‐Phenylethyl‐ATP (P‐ATP) was purchased from Biology Life Science Institute (Bremen, Germany) and N 6‐(2‐phenylethyl)‐2′‐deoxy‐ATP (d‐PATP) was synthesized by the same institute. Stocks of all ATP analogues were dissolved in double distilled H2O. VX‐770, supplied by Vertex Pharmaceuticals (Abingdon, UK) and Dr Robert Bridges (Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, IL, USA), was dissolved in DMSO. Special cleaning procedures as described previously (Jih & Hwang, 2013) were undertaken to avoid cross‐contamination of VX‐770 due to its ‘stickiness’.

The concentrations of all stock solutions and the storage methods were described below: P‐ATP (50 mM, −70°C), d‐PATP (50 mM, −70°C), PPi (200 mM, −20°C), d‐ATP (100 mM, −20°C), MgATP (250 mM, −20°C) and VX‐770 (100 μM, −70°C). Before patch‐clamp experiments, reagents were freshly thawed and diluted to the desired concentration indicated in each figure using the perfusion solution and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NMDG.

Data analysis and statistics

Single‐channel amplitudes of WT‐CFTR were measured from all‐points histograms. But the same method cannot be used for R117H‐CFTR because most of the opening events are brief with little open‐channel noise to work with and/or are filtered out to appear as subconductance openings. To obtain the microscopic I–V relationship for R117H‐CFTR (see Fig. 2 B), we decided to estimate the maximal single‐channel amplitude (i Max = i o – i c) by handpicking the opening events with a duration > 100 ms and calculating the difference between the mean open‐channel current amplitude (i o) and the baseline current amplitude (i c) with Igor (version 4.07; Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). For single‐channel kinetic analysis, data were collected from patches with fewer than four opening events using a program developed by Dr Csanády (Csanady, 2000; Bompadre et al. 2005 a). Current traces were baseline‐corrected, idealized and fitted to a three‐state model C ↔ O ↔ C′, where C represents a closed state from which ATP acts to open the channel, O is the open state and C′ represents a short‐lived closed state within an open burst. Fitting the dwell‐time histograms of all conductance levels yields the rate constants (r): r CO, r OC, r OC′ and r C′O. Then, the mean open burst time (τo), the mean interburst time (τc) and open probability (P o) were calculated as:

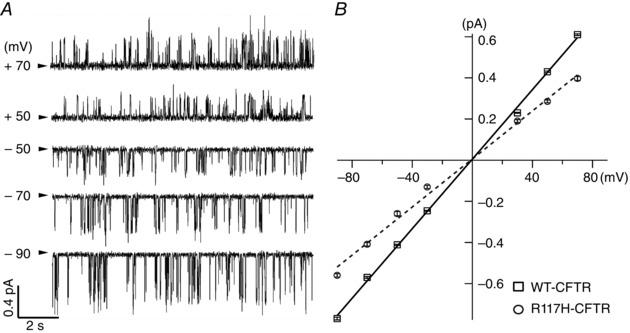

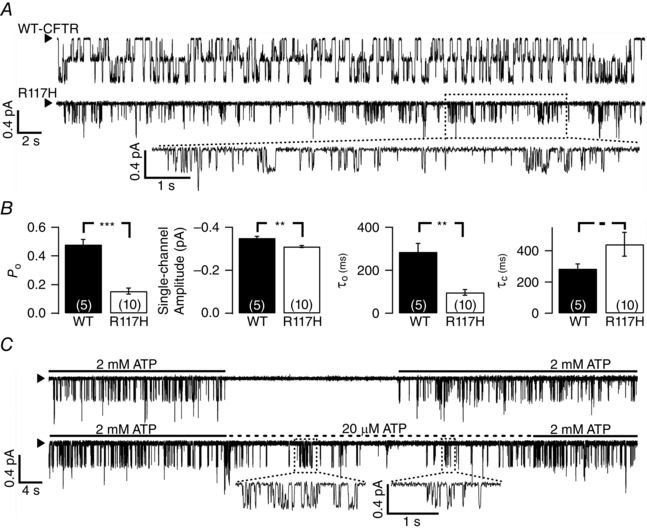

Figure 2. Decrease of the single‐channel conductance with R117H‐CFTR .

A, representative single‐channel current traces of R117H‐CFTR at different membrane potentials in the presence of 2 mM ATP. Single‐channel traces at −50 and +90 mV were analysed (P o_(−50 mV) = 0.16 ± 0.04; P o_(+90 mV) = 0.15 ± 0.04, n = 3; P = 0.47, paired t test). The arrowhead marks the baseline level (closed state). B, single‐channel I–V relationships for WT (black squares) and R117H‐CFTR (grey circles). Single‐channel amplitudes of R117H (i MAX) and WT‐CFTR were measured as described in the Methods. Fitting the data with a linear function yields a slope conductance of 6.08 ± 0.11 pS (n = 6) for R117H‐CFTR, which is ∼25% smaller than that of WT‐CFTR (8.02 ± 0.23 pS, n = 3).

Then, we followed the tradition of using the burst time (τb) to depict the ATP‐dependent mean open time (τo) and the interburst time (τib) for ATP‐dependent closed time (τc) (Csanady, 2000; Vergani et al. 2005; Tsai et al. 2010; Jih & Hwang, 2013).

While this program has been employed successfully for WT channels, for channels with very low activity, e.g. R117H‐CFTR, the number of channels in the membrane patch could not be ascertained and hence the program will overestimate the opening rate (r CO) as well as P o. However, this technical difficulty is partly overcome by our strategy of dramatically increasing P o with potentiators such as d‐PATP, VX‐770 and NO3 − applied together (see Fig. 12). While we used the same program to analyse the kinetics of R117H‐CFTR to make fair comparisons with the WT data, we are concerned if the simple C ↔ O ↔ C′ scheme used routinely for WT‐CFTR is applicable to R117H‐CFTR. To amend this potential technical issue, we employed classical single‐channel dwell‐time analysis for limited patches that contain only a single channel (see Fig. 9 for R117H and Fig. 10 for WT channels) with a home‐made program (Bompadre et al. 2005 a,b). If the C ↔ O ↔ C′ scheme is a valid but simplified gating scheme for CFTR gating, one expects to observe a single exponential distribution in the open dwell‐time histogram, but a double‐exponential distribution in the closed dwell‐time histogram. Indeed, the data presented in Figs 9 and 10 show just that.

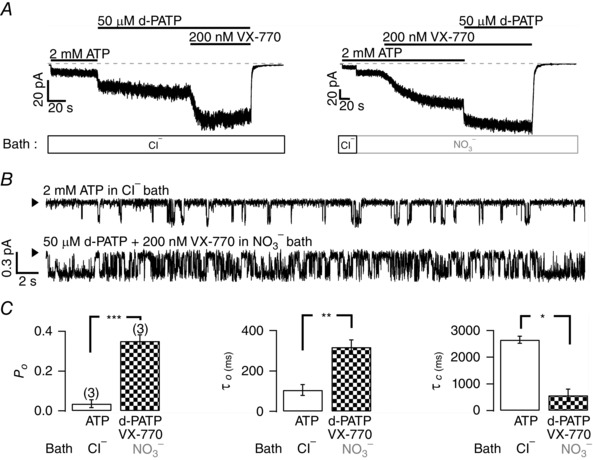

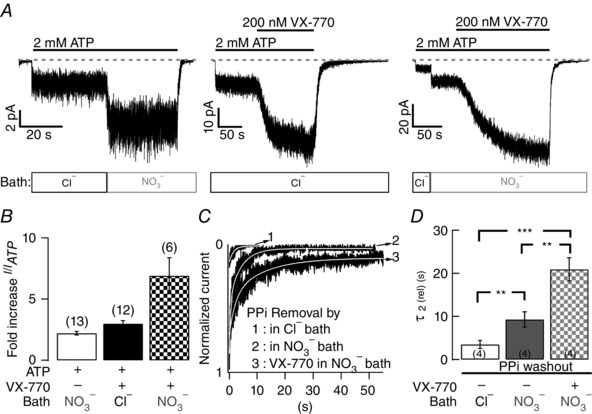

Figure 12. Near complete rectification of the gating defects of R117H‐CFTR by a combination of NO3−, VX‐770 and d‐PATP .

A, cooperative potentiation of R117H‐CFTR by d‐PATP, NO3 − and VX‐770. Representative macroscopic current traces showing an increase of d‐PATP‐activated R117H‐CFTR activity by VX‐770 in 154 mm Cl− bath solution (left panel), or a further enhancement of R117H‐CFTR activated with NO3 − plus VX‐770 by d‐PATP (right panel). B, single‐channel current traces for R117H‐CFTR in the presence of ATP alone or ATP plus all three potentiators (NO3 −, VX‐770 and d‐PATP). C, summary of single‐channel kinetics from three experiments. Of note, in the presence of all three potentiators, the P o of R117H‐CFTR reaches ∼ 75% of WT P o. ***P < 0.005; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05, two‐tailed, paired t test.

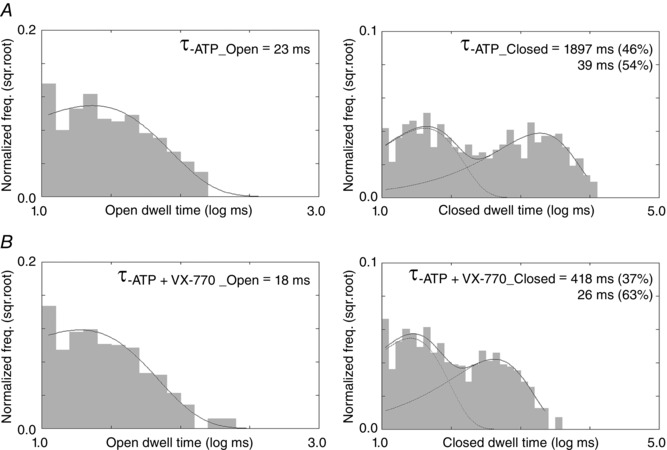

Figure 9. Effects of VX‐770 on single‐channel kinetics of R117H‐CFTR .

A, open dwell‐time and closed dwell‐time histograms of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of ATP alone. B, open dwell‐time and closed dwell‐time histograms of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of ATP plus VX‐770. Note the closed time distributions show two distinct components. Single‐channel dwell‐time analysis for data presented in Fig. 7A. Based on the closed‐time distributions, a delimiter of 160 ms was set for burst analysis. Results of burst analysis indicate that VX‐770 prolongs the burst time from 106 to 187 ms and shortens the interburst time from 1843 to 433 ms. This observation is qualitatively consistent with those presented in Fig. 7 B.

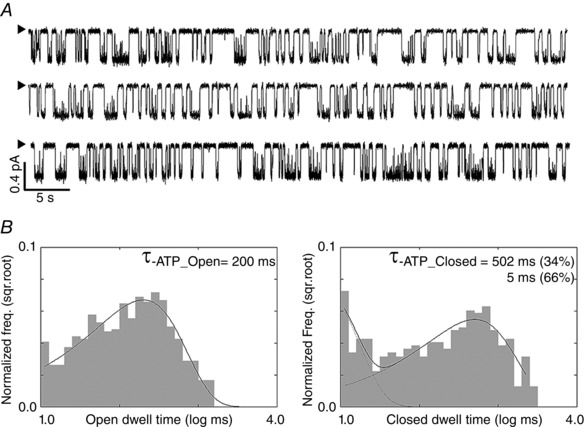

Figure 10. Single‐channel dwell‐time and burst analyses of ATP‐dependent gating of WT‐CFTR .

A, single‐channel current traces of WT‐CFTR in the presence of 2 mM ATP. To collect sufficient gating events for dwell‐time analysis, data from two different patches were pooled. B, open time and closed time histograms of WT‐CFTR. Mean open time as marked was obtained by fitting the histogram with a single exponential function. The closed time histogram can be fitted with a double exponential function to yield two closed time constants as indicated. Of note, the shorter closed time constant of 5 ms means a significant number of brief closings were missed due to the limited bandwidth of our recording. Nevertheless, burst analysis, carried out by using 30 ms as a delimiter, resulted in τburst = 386 ms and τinterburst = 480 ms, which are close to kinetic parameters reported previously for WT‐CFTR (Tsai et al. 2010). These results corroborate the conclusion that the R117H mutation decreases the rate of opening into the bursting state, and the duration the channel stays in the bursting state.

To obtain the parameters for intra‐burst kinetics (see Fig. 5 A and B) and ATP‐independent gating (see Fig. 6), we adopted a simple C ↔ O scheme in the Csanády program because no ATP is present in these two conditions. Here, the mean open time (τo) and the mean closed time (τc) are 1/r OC and 1/r CO, respectively.

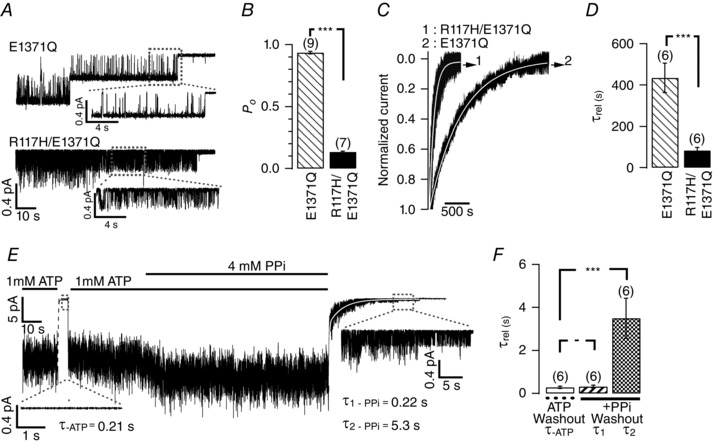

Figure 5. Abolition of ATP hydrolysis affects R117H‐CFTR gating .

A, single‐channel current traces of E1371Q‐CFTR and R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR in an ATP‐free solution. The traces encircled by the dashed grey boxes were expanded to show detailed gating transitions within a lock‐open state. B, comparison of the P o of E1371Q‐CFTR and R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR; data were obtained from the one single opening level in the absence of ATP. ***P < 0.005, one‐tailed, unpaired t test. C, representative macroscopic current decays recorded upon patch excision into an ATP‐free bath for E1371Q‐ (2) or R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR (1). Fitting the decay time course with a single exponential function (thin continuous line) yields a relaxation time constant (τrel) summarized in D. D, shortening of the relaxation time constant of E1371Q by the R117H mutation. *** P < 0.005, one‐tailed, unpaired t test. E, effects of PPi on R117H‐CFTR. A real‐time macroscopic R117H‐CFTR current trace showing a rapid monophasic current decay upon removal of ATP with a relaxation time constant of ∼0.2 s (white dashed line), but a biphasic current decay upon removal of ATP and PPi (white continuous line). Note characteristic flickering opening events (expanded trace) long after ATP washout similar to those shown in A. F, summary of relaxation time constants upon removal of ATP or ATP plus PPi for R117H‐CFTR. ***P < 0.005, two‐tailed, paired t test.

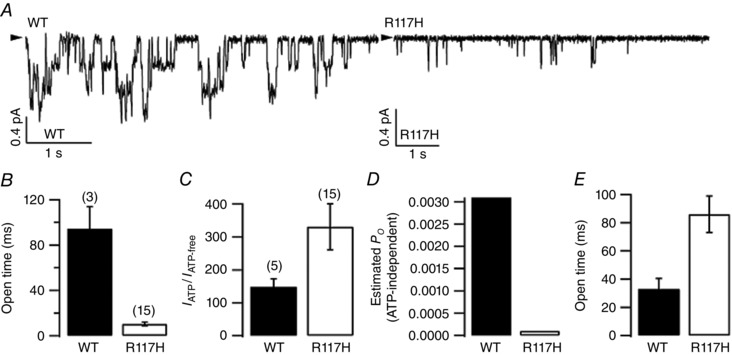

Figure 6. Effects of the R117H mutation on ATP‐independent gating .

To quantify ATP‐independent gating, macroscopic currents of phosphorylated CFTR channels were elicited with 2 mM ATP, followed by complete removal of ATP. To avoid dissociation of ATP from the catalysis‐incompetent site (Tsai et al. 2009, 2010), current traces within 10 s of ATP washout were collected and analysed. A, representative traces of WT‐ or R117H‐CFTR in the absence of ATP. B, open time constants for WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR in the absence of ATP. As described in the Methods, a simple C ↔ O scheme was used for kinetic analysis in recordings with a maximal number (N) of simultaneous opening steps ≤4. A near 10‐fold difference in the mean open time was noted. C, ratios of the mean current amplitudes before and after ATP removal (I ATP/I ATP‐free), representing the P o ratio for ATP‐dependent versus ATP‐independent gating. This result indicates that ATP‐independent gating is also reduced by the R117H mutation. D, estimated P o of ATP‐independent gating for WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR. As P o in the presence of 2 mm ATP (P o ATP) is known for WT as well as R117H channels, the P o for ATP‐independent gating (P o ATP‐free) can be calculated based on the formula: P o ATP‐free = P o ATP/(I ATP free/I ATP). E, calculated mean closed times in the absence of ATP for WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR. The mean closed time (τc) for ATP‐independent gating can be obtained from the equation: P o ATP‐free = τo/(τo + τc). Thus, the spontaneous ATP‐independent opening rate of R117H is ∼3‐fold slower than that of WT.

Other standard analyses such as measurements of macroscopic steady‐state current, curve fitting of macroscopic current decays with exponential functions, and curve fitting of the ATP dose–response relationship with the Hill equation were carried out with Igor.

Results are shown as mean ± SEM, and n represents the number of data points for each experiment. Student's t tests were performed using Excel (Microsoft). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

We investigated the gating abnormalities of R117H‐CFTR in excised inside‐out patches that have been exposed to PKA and ATP for tens of minutes to ensure that the channels are fully activated. Figure 1 A shows single‐channel activities of PKA‐phosphorylated wild‐type (upper trace) or R117H‐CFTR (lower trace) in the presence of 2 mM ATP. Two important differences are apparent from visual inspection of these traces. First, there is a different pattern of channel gating: while WT‐CFTR exhibits its characteristic burst opening events that last for hundreds of milliseconds (τo = 285 ± 39 ms, n = 5) and an open probability (P o) of 0.48 ± 0.04 (n = 5), most of the opening events for R117H‐CFTR are brief. Even with the expansion of the current trace (Fig. 1 A: dashed box), most of the observed opening events of R117H‐CFTR are shorter than 100 ms. When we assumed the number of active R117H‐CFTR channels is equal to the observed number of opening steps, the P o for this mutant CFTR, derived from the same analysis program used for WT channels, is ∼0.16 ± 0.02 (τo = 97 ± 14 ms, n = 10). In addition to gating anomalies, the second difference observed is a smaller single‐channel amplitude for R117H‐CFTR as reported previously (Sheppard et al. 1993; Hammerle et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2014).

Figure 1. Defective gating of R117H‐CFTR .

A, representative single‐channel current traces for WT‐CFTR and R117H‐CFTR. CFTR channels were pre‐activated by PKA‐dependent phosphorylation before they were exposed to a perfusion solution containing 2 mM ATP. An expanded trace of R117H‐CFTR in the dashed box shows more detail of individual opening events. The arrowhead in each trace represents the baseline level (closed state). B, comparisons of single‐channel kinetic parameters of WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005, one‐tailed, unpaired t test. C, ATP‐dependent gating of R117H‐CFTR. The upper panel shows that activated channels immediately return to the closed state upon removal of ATP. The lower trace shows a decrease of R117H‐CFTR activity when [ATP] is lowered to 20 μM. In the presence of 20 μM ATP, it is easier to discern bursts of brief opening events (dashed boxes) separated by prolonged interburst closures.

Figure 1 B summarizes the single‐channel kinetic parameters for WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR. Compared to that of WT‐CFTR, the P o of R117H‐CFTR is ∼3‐fold lower due to a shorter mean open time (τo) and a longer mean closed time (τc). Note that because the estimated P o for R117H‐CFTR is probably higher than the actual P o because of an underestimation of the number of active channels in the patch (see Figs 1 B, 4 B and 7 B), at this juncture our analysis inevitably underestimates the closed time constant. In addition to a shortened open time, the R117H mutation probably also decreases the opening rate, although the difference in the closed time constant between WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR is not yet statistically significant (Fig. 1 B). However, the difference shown in the single‐channel amplitude between WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR is consistent with that reported by Sheppard et al. (1993).

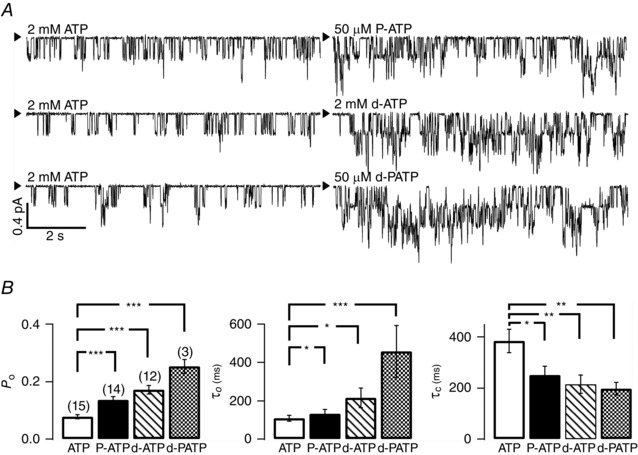

Figure 4. Potentiation of R117H‐CFTR activity by ATP analogues .

A, sample single‐channel recordings of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of ATP or various ATP analogues, P‐ATP, d‐ATP or d‐PATP. The arrowhead marks the baseline level (closed state). B, a summary of single‐channel kinetic parameters of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of ATP or ATP analogues. The gating effects of ATP analogues follow a sequence of efficacy of P‐ATP (50 μM) < d‐ATP (2 mM) < d‐PATP (50 μM). Note a P o of 0.08 ± 0.01 (n = 15) in the presence of ATP alone is lower than the value shown in Fig. 1 B due to an improved estimation of the number of channels in the patch. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005, one‐tailed, unpaired t test.

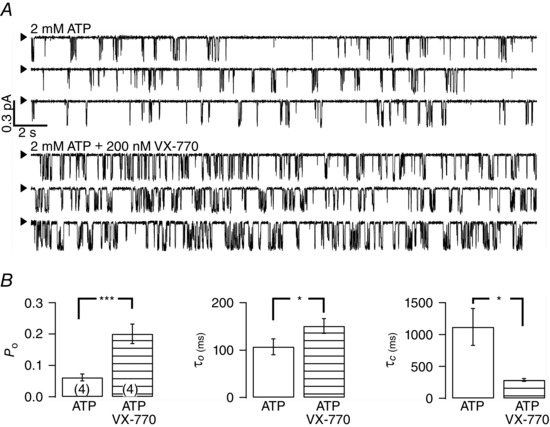

Figure 7. Potentiation of R117H‐CFTR gating by VX‐770 .

A, representative single‐channel recordings of R117H‐CFTR in the absence (upper panel) or presence of 200 nm VX‐770 (lower panel). The arrowhead indicates the baseline level (closed state). B, VX‐770 increases P o by prolonging the open time and shortening the closed time. Here again, the P o of 0.06 ± 0.01 in the presence of ATP alone is lower than the value shown in Fig. 1 B for the same reason described in the legend to Fig. 4. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.005, two‐tailed, paired t test.

Despite a lower P o, gating of R117H‐CFTR is ATP‐dependent as seen in Fig. 1 C. Removal of ATP results in a complete abolition of channel activity, which can be readily brought back by the re‐application of ATP. Although it is difficult to quantify ATP‐independent gating in patches with few channels, it appears that R117H‐CFTR rarely opens in the absence of ATP because this mutation increases the energetic barrier for gate opening in the absence of the ligand ATP (also see the first expanded trace in Fig. 5 E). The lower panel of Fig. 1 C shows a real‐time trace where [ATP] is reduced to 20 μM to prolong the ATP‐dependent closed events. Under this condition, one can more easily discern ‘burst opening’ behaviour (e.g. expanded traces in the dashes showing frequent openings interrupted by distinct closures). If we, for now, accept the expanded traces as individual open bursts, that means, compared to WT‐CFTR, the R117H mutant exhibits an unstable bursting open state that transits to a closed state repeatedly during an open burst. Furthermore, while within an open burst, the closures for WT‐CFTR are very brief, this is not the case for the R117H mutant. This interpretation will be revisited below.

First let us consider another possibility for this unusual ‘gating’ behaviour of R117H‐CFTR. It has been shown previously that some of the ‘closing’ events in an open burst for WT‐CFTR are attributed to pore blockade by bulky anions in the perfusion solution or inside the cell (Zhou et al. 2001). Thus, it is possible that the frequent interruptions of the open‐channel current of the R117H mutant are due to enhanced block by the mutation. As there is a strong voltage dependence for this kind of pore‐block mechanism, a straightforward way to test this idea is to examine the single‐channel behaviour at both negative and positive membrane potentials. As seen in Fig. 2 A, the gating behaviour of R117H‐CFTR does not change noticeably with respect to different holding potentials. Indeed, kinetic analysis of the data recorded at −50 and +90 mV show nearly identical P o (see legend to Fig. 2). Thus, the R117H mutation probably destabilizes the conformation of the open burst state, but stabilizes a closed state that is visited during an open burst. Figure 2 B shows a complete I–V relationship for R117H‐CFTR (circles and dashed line), which can be fitted nicely with a straight line with a slope of 6.08 (6.08 ± 0.11 pS, n = 6), which is ∼25% lower than that of WT‐CFTR (8.02 ± 0.23 pS, n = 3, squares and continuous line).

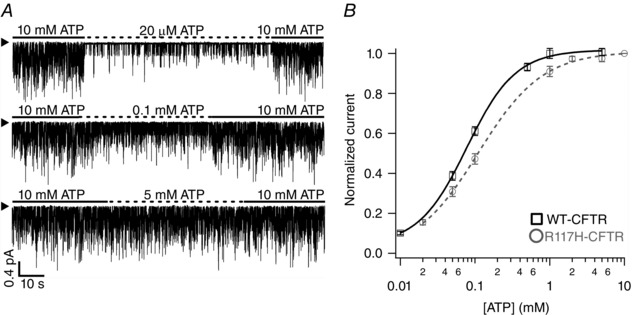

To further explore the mechanism of the gating defects associated with the R117H mutant, we next examined if the R117H mutation alters the sensitivity of the channel to ATP by exposing the channels to different concentrations of ATP, [ATP]. Figure 3 A shows the representative experimental protocols and results. Here 10 mM ATP was used as a reference concentration to normalize the current response to various [ATP]. While 20 μM ATP yields an activity that is much lower than that of 10 mM ATP, 0.1 mM seems to generate ∼50% of the activity seen at 10 mM ATP. Indeed, fitting the dose–response relationship with the Hill equation (Fig. 3 B) gives an EC50 of ∼0.11 mM ATP and a Hill coefficient of ∼1. These are very similar to the results with WT‐CFTR (Zhou et al. 2006).

Figure 3. [ATP]‐dependent gating of R117H‐CFTR .

A, representative R117H‐CFTR current traces at different ATP concentrations as marked. The arrowhead marks the baseline level (closed state). B, ATP dose–response relationship for R117H‐CFTR. Each data point represents mean ± SEM from eight patches; normalized current was defined by the equation Imeasured/I[ATP]max. The grey dashed line represents fitting of the data (R117H‐CFTR) with a standard Hill equation: Hill co‐efficient = 1.01; K 1/2 = 0.11 ± 0.01 mM. The fitted curve for the dose–response relationship of WT channels (black continuous line) is shown for comparison.

The observation that the R117H mutation poses minimal effects on CFTR's sensitivity to ATP suggests that the mutation may not affect the function of CFTR's NBDs. Indeed, Fig. 4 A illustrates significant enhancements of R117H‐CFTR channel activity by all three ATP analogues, P‐ATP, d‐ATP and d‐PATP, that have been shown previously to enhance gating of WT‐CFTR as well as disease‐associated mutants (Zhou et al. 2005; Bompadre et al. 2008; Miki et al. 2010; Tsai et al. 2010; Jih et al. 2011; Csanady et al. 2013). Kinetic analysis reveals that these analogues increase the P o of R117H‐CFTR by shortening the closed time and prolonging the open time, very similar qualitatively to their effects on WT channels. In addition, d‐PATP, which possesses the dual chemical features of P‐ATP and d‐ATP (Miki et al. 2010), is most effective in potentiating the activity of R117H‐CFTR (Fig. 4 B).

The current traces shown in Fig. 4 A also expose a technical difficulty commonly encountered in estimating the P o of R117H‐CFTR or any mutant channels with a much reduced P o (Bompadre et al. 2007). In all three traces, the maximal number of opening levels is two in the presence of ATP alone, whereas three levels of open‐channel currents can be discerned when the ligand was changed to any one of the ATP analogues. However, the P o for d‐PATP‐activated R117H‐CFTR remains lower than 0.3 (0.25 ± 0.02, n = 3). Thus, it is still possible that the number of active channels in the patch was underestimated, resulting in an overestimation of P o. Nonetheless, with an increase of P o, the error introduced when assigning the number of active channels is hence decreased. This may explain why the P o of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of ATP alone (Fig. 4 B: 0.08 ± 0.01, n = 15) in this series of studies is ∼6‐fold lower than that of WT channels (cf. Fig. 1 B).

While the data above suggest relatively intact NBDs in R117H‐CFTR, we were surprised that one recent report shows that AMP‐PNP, a non‐hydrolysable ATP analogue, fails to lock‐open R117A‐CFTR, and hence concludes a dysfunction of NBDs caused by the mutation (Cui et al. 2014). In an early report, Carson et al. (1995) showed an enhancement of macroscopic R117H‐CFTR currents by pyrophosphate (PPi), a phosphate analogue with similar actions on CFTR gating as AMP‐PNP, without characterizing its effects on gating kinetics. We first took a different approach to address this issue: by introducing the E1371Q mutation (Gadsby et al. 2006) into R117H‐CFTR, we effectively eliminated ATP hydrolysis. By examining the current relaxation upon excising the patch into an ATP‐free solution, we were able to observe the details of single‐channel current transitions at the very end of the current decay when there was only one channel remaining open. Figure 5 A shows a representative recording of E1371Q‐CFTR in the absence of ATP, where stepwise closures of two channels can be readily discerned. In the expanded trace, one can see that the channel spends most of the time in the open state with occasional brief closings, yielding a P o of 0.94 ± 0.01 (n = 9), τo of 486 ± 76 ms and τc of 29 ± 4 ms within a locked‐open burst (Fig. 5 B). In contrast, when a similar experiment was carried out with the double mutant R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR, during the prolonged, lock‐open burst, the channel spends most of the time in the closed state with occasional short openings, resulting in a P o of ∼0.1 (0.13 ± 0.02, n = 7), and τo = 12 ± 4 ms and τc = 85 ± 21 ms.

We next quantified the macroscopic current relaxation time courses for E1371Q‐ and R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR (Fig. 5 C). The current decays of E1371Q‐CFTR upon patch excision into an ATP‐free solution can be well fitted with a single exponential function (solid white lines overlapping the raw traces). Compared to E1371Q‐CFTR, macroscopic currents of the double mutant (R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR) decay at least 5‐fold faster (Fig. 5 D). This result suggests that the R117H mutation does not prevent the hydrolysis‐deficient CFTR from being locked into an ‘open burst’ state when the channel's activity does not need the continuous presence of ATP. However, the stability of this lock‐open state is compromised by the R117H mutation.

We next examined the effects of PPi on R117H‐CFTR. Figure 5 E shows a representative experimental result where PKA‐phosphorylated R117H‐CFTR channel currents were elicited with ATP alone; removal of ATP resulted in a rapid decay of the current with a time constant of 0.28 ± 0.05 s (n = 6). It was noted that in the absence of ATP (the first expanded trace), there are seldom any opening events despite the existence of plentiful channels in this patch. Detailed analysis of ATP‐independent gating indeed shows a difference between WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR (Fig. 6). Interestingly, application of PPi did increase the steady state currents (I PPi/I ATP = 1.57 ± 0.18, n = 6) and subsequent removal of ATP and PPi caused a biphasic current decay. Fitting the decay phase with a double exponential function (the second solid white curve in Fig. 5 E) yields a short time constant (τ1_PPi washout = 0.32 ± 0.07 s, n = 6) that is very similar to the one after removal of ATP (τ_ATP washout = 0.28 ± 0.05 s, n = 6; Fig. 5 F), and a long time constant of ∼3.5 s (τ2_PPi washout = 3.49 ± 0.05 s, n = 6) (vs. ∼30 s for WT‐CFTR in Tsai et al. 2009). The expanded trace at the end of the recording in Fig 5 E also shows repeated brief opening events after ATP/PPi has been long washed out similar to those observed for R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR (Fig. 5 A). Kinetic analysis of events of R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR within this prolonged burst yields a P o of ∼0.1 (0.13 ± 0.02, n = 7), and τo = 11.5 ± 3.6 ms and τc = 84.6 ± 4.2 ms.

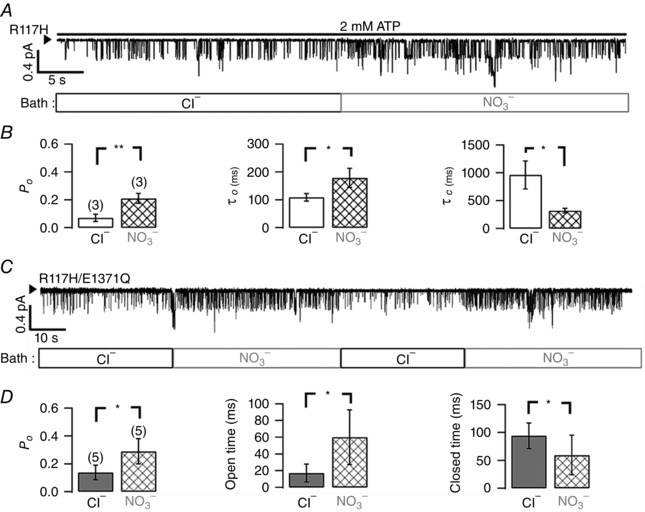

While the experiments so far demonstrate that gating of R117H‐CFTR is subjected to manipulations of NBD function, we next examined the effects of reagents that were proposed to affect the gating conformational changes of CFTR's TMDs, namely VX‐770 and nitrate (Jih & Hwang, 2013; Yeh et al. 2015). Figure 7 A shows single‐channel current traces of R117H before and after the application of VX‐770. Visual inspection of the raw traces reveals that in the presence of ATP alone, there exist numerous closed events that are longer than 1 s; however, in the presence of VX‐770, the prolonged closed events are shortened, whereas at the same time each apparent open burst seemed lengthened. Kinetic analysis of the data from R117H (n = 4) indeed shows an increase of P o by VX‐770 due to a decrease of τc and an increase of τo (Fig. 7 B). Similar observations at a microscopic level were made with nitrate (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Effects of nitrate on R117H‐CFTR gating .

A, representative single‐channel trace of R117H‐CFTR with 2 mM ATP in chloride or nitrate bath as indicated. B, nitrate increases the P o of R117H‐CFTR by prolonging the open (open burst) time and shortening the closed (interburst) time, effects similar to those of VX‐770 (cf. Fig. 7). **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05, two‐tailed, paired t test. C, single‐channel trace of R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR after ATP removal to show effects of nitrate on gating transitions in the absence of ATP. By eliminating ATP‐dependent events and ATP hydrolysis, we simplified our analysis to extract directly the open time and the closed time. D, nitrate increases the P o of R117H/E1371Q‐CFTR within a lock‐open burst by increasing the open time and decreasing the closed time, effects similar to those of nitrate on R117H‐CFTR. *P < 0.05, two‐tailed, paired t test.

As described in the Methods, although the program used routinely for WT channels (Csanady, 2000) is very valuable as it allows analysis of recordings containing multiple channels, we were concerned if the imposed C ↔ O ↔ C′ scheme is applicable to R117H‐CFTR. Data from a patch containing only one single channel as shown in Fig. 7 A, although rare, offer an opportunity to carry out classical single‐channel dwell‐time analysis by constructing open‐ and closed‐time histograms (Fig. 9). In the presence of ATP alone or ATP plus VX‐770, the open‐time histograms can be fitted with a single exponential function, but the closed‐time histograms show two apparent peaks. Using the value at the nidus of the two distributions in the closed‐time histogram as a delimiter (∼160 ms), we carried out single‐channel burst analysis and observed a prolongation of the burst time (from 106 to 187 ms) and a shortening of the interburst time (from 1843 to 433 ms) by VX‐770. These values, from a different kind of kinetic analysis, are not far from the numbers shown in Fig. 7 B, and hence reaffirm the conclusion that the R117H mutation decreases the opening rate as well as the open time. (Fig. 10 shows similar analysis for WT‐CFTR.) Furthermore, similar results from these two different analyses also strengthen our conclusion that VX‐770 improves R117H‐CFTR function by shortening the closed time and prolonging the open time, kinetic effects qualitatively similar to that of VX‐770 on WT channels (Jih & Hwang, 2013).

Figure 11 shows responses of macroscopic R117H‐CFTR currents to nitrate, VX‐770 or a combination of both reagents. As summarized in Fig. 11 B, the effect of VX‐770 plus nitrate on R117H‐CFTR is larger than the sum of effects from individual reagents. [Of note, a qualitatively similar observation was made previously for G551D‐CFTR, another disease‐associated mutation, by Yeh et al. (2015).] This synergistic effect can also be demonstrated by a different assay that measures the relaxation time constant of PPi‐locked open channels. As seen in Fig. 11 C, the current decay for PPi‐locked open R117H‐CFTR is prolonged by nitrate or nitrate plus VX‐770 (Fig. 11 D).

Figure 11. Synergistic effects of VX‐770 and nitrate on R117H‐CFTR gating .

A, enhancement of macroscopic R117H‐CFTR currents by nitrate, VX‐770 or a combination of both reagents in excised inside‐out patches. The open bars under the current traces mark the major anion present in the cytoplasmic solution: 154 mM Cl−; NO3 −: 154 mM NO3 − (also applicable to Fig. 12). The grey dashed line indicates the baseline level (closed state). B, summary of the potentiation effect represented as fold‐increase of the macroscopic currents shown in A. C, prolongation of the PPi‐lock open R117H‐CFTR by nitrate or nitrate plus VX‐770. The current decay phases upon removal of ATP and PPi in different conditions as indicated (1, Cl−‐containing perfusate; 2, NO3 −‐containing perfusate; 3, VX‐770 in NO3 −‐containing perfusate) are shown. Thin continuous line within each trace represents fits of the current decay with a double‐exponential function. D, summary of the second, longer relaxation time constants obtained from C. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005, two‐tailed, paired t test.

To strive for a better quantitative assessment of the gating defect associated with the R117H mutation, we tested the idea that the P o of R117H‐CFTR can be further augmented by adding VX‐770 or nitrate to d‐PATP, the most effective ATP analogue shown in Fig. 4. Indeed, Fig. 12 A shows that VX‐770 can increase macroscopic R117H‐CFTR currents elicited with d‐PATP and that d‐PATP also slightly increases currents potentiated with VX‐770 plus nitrate. With these results in mind, we then looked into single‐channel behaviour of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of all three reagents. As seen in Fig. 12 B, in the presence of ATP only, closed events longer than 1 s are often seen, indicating a prolonged closed time with the R117H‐CFTR. However, when all three reagents are present, a robust activity of the channel is seen, resulting in a P o of 0.35 ± 0.03 (n = 3), close to that of WT channels (Fig. 12 C). Thus, the technical issue discussed above is mitigated and a more accurate P o in the presence of ATP alone (0.035 ± 0.020, n = 3) – the presumed physiological condition – can be attained.

Discussion

In the current study, we first confirmed previous results that the arginine to histidine substitution at position 117 of CFTR, a mutation that is associated with mild‐form CF (Sheppard et al. 1993), affects both gating and ion conduction of the CFTR chloride channel. By characterizing in detail the response of R117H‐CFTR to ATP and its analogues, we demonstrated that this mutation might not affect nucleotide binding to the channel. In contrast to a recent report (Cui et al. 2014), our data also suggest that the NBDs in R117H‐CFTR can form a stable dimer once ATP hydrolysis is abolished. By examining the gating behaviour of hydrolysis‐disabled R117H‐CFTR, we conclude that the normally stable conformation of the open state with dimerized NBDs is destabilized by the mutation (see below for a more complete deliberation). Finally, by testing the gating effects of individual pharmacological reagents or a combination of drugs, we were able to push the P o of R117H‐CFTR to ∼75% of that of WT channels, and subsequently obtained a more accurate assessment of the gating abnormalities associated with this pathogenic mutation.

The gating defect associated with R117H‐CFTR poses two technical challenges for a better understanding of this gating abnormality. First, because of a much reduced P o, the probability of simultaneous opening of multiple channels in a recording system can be exceedingly low, resulting in an unavoidable underestimation of the number of active channels. This is probably the main reason why previous studies have cautiously refrained from giving a definitive value for P o or obtained a much lower reduction of P o (Sheppard et al. 1993; Hammerle et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2014). Sheppard et al. (1993) were the first to characterize R117H‐CFTR at the single‐channel level. Compared to WT‐CFTR, the mutant channel exhibits a smaller single‐channel amplitude and a lower open probability. Although this early study did not report gating kinetic parameters, their observation that R117H‐CFTR shows much shorter opening events was reproduced in the current study. However, it is not easy to explain why the same mutant exhibits different gating behaviour in reconstituted bilayers (Hammerle et al. 2001), although these characteristic gating anomalies of R117H‐CFTR were also seen with other mutations at the R117 position (e.g. R117C, R117L and R117P) in the same report. A recent paper also demonstrates similar gating anomalies with the R117A and R117E mutations (Cui et al. 2014).

Second, the brief openings seen with R117H‐CFTR also make it difficult to employ a commonly used kinetic analysis program that has been applied successfully for WT‐CFTR to extract kinetic parameters (Csanady, 2000). Although, for the sake of a fair comparison between WT‐ and R117H‐CFTR, this program was employed to analyse R117H‐CFTR data, we did realize its potential problems. While we caution our readers with this potential caveat, for whatever interpretations we intend to make, the raw current traces should always serve as our guide. Whenever possible, traditional single‐channel dwell‐time analysis will be carried out to offer additional evidence corroborating our conclusions (e.g. Figs 9 and 10).

Taking advantage of the pharmacological reagents and ATP analogues studied extensively over the years (Zhou et al. 2005; Miki et al. 2010; Tsai et al. 2010; Jih et al. 2011), we were able to dramatically potentiate the activity of R117H‐CFTR. Once the P o of this mutant CFTR can be increased to the level close to that of WT‐CFTR, assignment of the number of active channels in the patch can be done more accurately. Subsequently, the P o of R117H‐CFTR in the presence of ATP alone can be back calculated. This analysis provides critical information regarding the opening rate of the ATP‐gated R117H‐CFTR channel that is not easily assessed without an accurate estimation of the number of active channels. Figure 12 C shows that the gating defects of R117H‐CFTR include both a shortened open time and a prolonged closed time, echoing results from traditional single‐channel kinetic analysis (Figs 9 and 10). Importantly, these kinetic parameters derived from the analysis program for WT channels are reasonably agreeable with the gating behaviour seen with the raw trace (Fig. 12 B).

Our next goal is to grasp, on the basis of a recent gating model (Jih & Hwang, 2012), a molecular understanding of the gating defects induced by the R117H mutation, which may probably also be applicable to other pathogenic mutations at this position (e.g. R117C). It has been proposed that opening and closing of the gate in CFTR's TMDs are coupled respectively to ATP‐binding‐induced NBD dimerization and hydrolysis‐triggered NBD dissociation (Gadsby et al. 2006). Our recent studies not only suggest that this coupling between the gating cycle and ATP hydrolysis cycle is not as strict as once thought (Jih & Hwang, 2012), but also pinpoint the location of the gate in CFTR's TMDs (Gao & Hwang, 2015). Regardless of the exact nature of the coupling mechanism, it is generally accepted that once ATP hydrolysis is abolished, WT‐CFTR will stay in an open burst state for tens to hundreds of seconds (e.g. Fig. 5 A), and the long lifetime of this state at least partly reflects a stable NBD dimer (Gadsby et al. 2006; Mense et al. 2006; Jih & Hwang, 2012). For WT‐CFTR, the P o within such an open burst is close to unity as the gate is open for most of the time with occasional brief closures (Fig. 5 A and B). In contrast, under the same condition, we observed brief openings interrupted by relatively long closings with the R117H/E1371Q mutant (Fig. 5 A). Nonetheless, the fact that this bursting state does exist for a few seconds or tens of seconds in the complete absence of ATP suggests that a stable NBD dimer can be formed with the R117H‐CFTR. Once we accept this interpretation, it follows that the gate in R117H‐CFTR can easily close and stay closed for tens of milliseconds even with dimerized NBDs. In the context of the model proposed by Jih & Hwang (2012), it simply means that the R117H mutation shifts the opening/closing transitions of the gate in TMDs to the closed conformation. In other words, the R117H mutation destabilizes the open gate, but stabilizes the closed gate even when NBDs are kept in a dimerized form. This intrinsic effect of R117H on the gate in TMDs also explains why, in the absence of ATP when the NBDs are mostly in a partially separated form (Tsai et al. 2009, 2010), we rarely observed spontaneous ATP‐independent opening events (Fig. 6).

Despite a drastic perturbation of the stability of the gate in the TMDs of R117H‐CFTR, the mutant channel's activity remains ATP‐dependent. Furthermore, the P o of R117H‐CFTR can be effectively enhanced with ATP analogues (Zhou et al. 2005, 2006), which, by presumably facilitating the NBD dimerization steps that precede gate opening, can increase the opening rate (Fig. 4 B). On the other hand, by acting on the catalysis‐incompetent site (Zhou et al. 2006; Tsai et al. 2010), the analogue can also prolong the open burst of R117H‐CFTR (Fig. 4 B). For nitrate and VX‐770, as proposed previously (Jih & Hwang, 2013; Yeh et al. 2015), these two reagents can shift the gating transition of CFTR's TMDs towards the open channel conformations for WT as well as mutant CFTR, and hence increase the P o of R117H‐CFTR (Figs 7 and 8). As they bind to different sites in CFTR (Yeh et al. 2015), their synergistic effects on R117H‐CFTR gating were expected (Fig. 11 B). Then by acting on different sites or gating transitions, ATP analogues and nitrate/VX‐770 should also work independently and cooperatively (Fig. 12). Indeed, it is the presence of all three reagents that allows us to push the P o of R117H‐CFTR to ∼0.35 and thereby enables a more accurate assessment of the magnitude of its gating deficits.

Topologically, R117 is located at the ECL1 of CFTR. Several disease‐associated mutations have been identified in this region of the CFTR protein (Hammerle et al. 2001). Interestingly, unlike the most common pathogenic mutation F508del, these mutations do not cause trafficking defects; instead, gating and conductance defects were demonstrated. By quantitatively assessing both anomalies, we come to a conclusion that the gating defect contributes much more to the overall functional deficient in R117H‐CFTR than the reduction of single‐channel conductance. We therefore propose that it is more appropriate to sort R117H into Class III instead of Class IV mutations.

By integrating both gating and conductance defects, we can now calculate how much reduction of the overall transepithelial chloride flux is expected with the R117H mutation. As macroscopic chloride currents (I) carried by CFTR are determined by the number of channels in the cell membrane (N), the open probability (P o) of each channel and the single‐channel amplitude (i Max), we estimated that the R117H mutation decreases chloride flux by ∼17‐fold (25% reduction of i and 13‐fold decrease of P o). As the majority of patients carrying the R117H mutation are heterozygotes, the actual magnitude of the reduction of chloride flux in vivo will be ∼34‐fold if we assume the channels derived from the other allele are non‐functional. In contrast, our previous studies suggest that the G551D mutation, which causes a severe CF phenotype, results in a ∼120‐fold decrease of I. This difference in diminution of overall chloride flux between these two CF‐causing mutations may well explain their phenotypical differences: [Cl−]sweat ≅ 100 mmol/L for G551D‐carrying patients and 70–80 mmol/L for their counterparts carrying the R117H mutation (Wilschanski et al. 1995; Ramsey et al. 2011; Moss et al. 2015).

The observation that VX‐770 increases the P o of R117H‐CFTR by ∼3‐fold (Fig. 7) provides the underlying reason for recent success in a phase III clinical trial (NCT01614457; Moss et al. 2015); a 24 week treatment of patients carrying the R117H mutation significantly improved both respiratory symptoms and sweat chloride concentrations. Note, however, in those patients taking VX‐770 (ivacaftor), the sweat chloride remains above 60 mmol/L a threshold concentration considered pathognomonic. In addition, the improvement in lung function is somewhat limited, indicating a necessity for further enhancement of R117H‐CFTR activity. Indeed, the current report together with basic studies of CFTR gating mechanism (e.g. Jih et al. 2012) suggest insights into future development of therapeutic reagents that may complement the action of VX‐770.

Additional information

Competing interests

The current work is supported in part by Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. In total, 100% of Y.C.Y.’s effort and 5% of T.C.H.’s effort were financially supported by this funding source. No other financial relationships exist with any organization that might have an interest in the submitted work; no other relationships or activities exist that could appear to have influenced this submitted work.

Author contributions

T.C.H. designed and supervised the project. T.C.H. and Y. Sohma were also involved actively in writing, and revising the manuscript. Y.C.Y. performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper. Y.S. analysed and interpreted data.

Funding

The current work is supported in part by Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. It is also supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (NIHR01DK55835), the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Hwang15G0) and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 25293049, 15K15035.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cindy Chu and Shenghui Hu for their technical assistance and Dr Robert Bridges and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated for providing VX‐770.

This is an Editor's Choice article from the 15 June 2016 issue.

References

- Bai Y, Li M & Hwang TC (2010). Dual roles of the sixth transmembrane segment of the CFTR chloride channel in gating and permeation. J Gen Physiol 136, 293–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompadre SG, Ai T, Cho JH, Wang X, Sohma Y, Li M & Hwang TC (2005. a). CFTR gating I: characterization of the ATP‐dependent gating of a phosphorylation‐independent CFTR channel (ΔR‐CFTR). J Gen Physiol 125, 361–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompadre SG, Cho JH, Wang X, Zou X, Sohma Y, Li M & Hwang TC (2005. b). CFTR gating II: effects of nucleotide binding on the stability of open states. J Gen Physiol 125, 377–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompadre SG, Li M & Hwang TC (2008). Mechanism of G551D‐CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) potentiation by a high affinity ATP analog. J Biol Chem 283, 5364–5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompadre SG, Sohma Y, Li M & Hwang TC (2007). G551D and G1349D, two CF‐associated mutations in the signature sequences of CFTR, exhibit distinct gating defects. J Gen Physiol 129, 285–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MR, Winter MC, Travis SM & Welsh MJ (1995). Pyrophosphate stimulates wild‐type and mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl– channels. J Biol Chem 270, 20466–20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O'Riordan CR & Smith AE (1990). Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell 63, 827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanady L (2000). Rapid kinetic analysis of multichannel records by a simultaneous fit to all dwell‐time histograms. Biophys J 78, 785–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanady L, Mihalyi C, Szollosi A, Torocsik B & Vergani P (2013). Conformational changes in the catalytically inactive nucleotide‐binding site of CFTR. J Gen Physiol 142, 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Rahman KS, Infield DT, Kuang C, Prince CZ & McCarty NA (2014). Three charged amino acids in extracellular loop 1 are involved in maintaining the outer pore architecture of CFTR. J Gen Physiol 144, 159–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalemans W, Barbry P, Champigny G, Jallat S, Dott K, Dreyer D, Crystal RG, Pavirani A, Lecocq JP & Lazdunski M (1991). Altered chloride ion channel kinetics associated with the ΔF508 cystic fibrosis mutation. Nature 354, 526–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning GM, Ostedgaard LS, Cheng SH, Smith AE & Welsh MJ (1992). Localization of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in chloride secretory epithelia. J Clin Invest 89, 339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hiani Y & Linsdell P (2010). Changes in accessibility of cytoplasmic substances to the pore associated with activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. J Biol Chem 285, 32126–32140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC & Nairn AC (1999). Regulation of CFTR Cl– ion channels by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res 33, 79–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Vergani P & Csanady L (2006). The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis. Nature 440, 477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X & Hwang TC (2015). Localizing a gate in CFTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 2461–2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haardt M, Benharouga M, Lechardeur D, Kartner N & Lukacs GL (1999). C‐terminal truncations destabilize the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator without impairing its biogenesis. A novel class of mutation. J Biol Chem 274, 21873–21877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerle MM, Aleksandrov AA & Riordan JR (2001). Disease‐associated mutations in the extracytoplasmic loops of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator do not impede biosynthetic processing but impair chloride channel stability. J Biol Chem 276, 14848–14854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih KY & Hwang TC (2012). Nonequilibrium gating of CFTR on an equilibrium theme. Physiology (Bethesda) 27, 351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih KY & Hwang TC (2013). Vx‐770 potentiates CFTR function by promoting decoupling between the gating cycle and ATP hydrolysis cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 4404–4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih KY, Li M, Hwang TC & Bompadre SG (2011). The most common cystic fibrosis‐associated mutation destabilizes the dimeric state of the nucleotide‐binding domains of CFTR. J Physiol 589, 2719–2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih KY, Sohma Y & Hwang TC (2012). Nonintegral stoichiometry in CFTR gating revealed by a pore‐lining mutation. J Gen Physiol 140, 347–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazrak A, Fu L, Bali V, Bartoszewski R, Rab A, Havasi V, Keiles S, Kappes J, Kumar R, Lefkowitz E, Sorscher EJ, Matalon S, Collawn JF & Bebok Z (2013). The silent codon change I507‐ATC→ATT contributes to the severity of the ΔF508 CFTR channel dysfunction. FASEB J 27, 4630–4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs GL, Chang XB, Bear C, Kartner N, Mohamed A, Riordan JR & Grinstein S (1993). The ΔF508 mutation decreases the stability of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in the plasma membrane. Determination of functional half‐lives on transfected cells. J Biol Chem 268, 21592–21598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mense M, Vergani P, White DM, Altberg G, Nairn AC & Gadsby DC (2006). In vivo phosphorylation of CFTR promotes formation of a nucleotide‐binding domain heterodimer. EMBO J 25, 4728–4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H, Zhou Z, Li M, Hwang TC & Bompadre SG (2010). Potentiation of disease‐associated cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutants by hydrolyzable ATP analogs. J Biol Chem 285, 19967–19975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio K, Ogura T, Mio M, Shimizu H, Hwang TC, Sato C & Sohma Y (2008). Three‐dimensional reconstruction of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel revealed an ellipsoidal structure with orifices beneath the putative transmembrane domain. J Biol Chem 283, 30300–30310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss RB, Flume PA, Elborn JS, Cooke J, Rowe SM, McColley SA, Rubenstein RC, Higgins M & Group VXS (2015). Efficacy and safety of ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis who have an Arg117His‐CFTR mutation: a double‐blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 3, 524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MP, Ishihara H, Sheppard DN & Welsh MJ (1996). Function of Xenopus cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl channels and use of human–Xenopus chimeras to investigate the pore properties of CFTR. J Biol Chem 271, 25184–25191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM (1990). Cystic fibrosis: a disease in electrolyte transport. FASEB J 4, 2709–2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, Tullis E, Bell SC, Drevinek P, Griese M, McKone EF, Wainwright CE, Konstan MW, Moss R, Ratjen F, Sermet‐Gaudelus I, Rowe SM, Dong Q, Rodriguez S, Yen K, Ordonez C, Elborn JS & Group VXS (2011). A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med 365, 1663–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et al (1989). Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245, 1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MB, Choe KA & Joseph PM (2006). Review of the abdominal manifestations of cystic fibrosis in the adult patient. Radiographics 26, 679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MF, Kamis AB, Aleksandrov LA, Ford RC & Riordan JR (2004). Purification and crystallization of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). J Biol Chem 279, 39051–39057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert FS, Chang XB, Aleksandrov AA, Clarke DM, Hanrahan JW & Riordan JR (1999). Influence of phosphorylation by protein kinase A on CFTR at the cell surface and endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1461, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DN, Rich DP, Ostedgaard LS, Gregory RJ, Smith AE & Welsh MJ (1993). Mutations in CFTR associated with mild‐disease‐form Cl– channels with altered pore properties. Nature 362, 160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MF, Li M & Hwang TC (2010). Stable ATP binding mediated by a partial NBD dimer of the CFTR chloride channel. J Gen Physiol 135, 399–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MF, Shimizu H, Sohma Y, Li M & Hwang TC (2009). State‐dependent modulation of CFTR gating by pyrophosphate. J Gen Physiol 133, 405–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, Turnbull A, Singh A, Joubran J, Hazlewood A, Zhou J, McCartney J, Arumugam V, Decker C, Yang J, Young C, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M & Negulescu P (2009). Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX‐770. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 18825–18830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, Decker CJ, Miller M, McCartney J, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M & Negulescu PA (2011). Correction of the F508del‐CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX‐809. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 18843–18848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergani P, Lockless SW, Nairn AC & Gadsby DC (2005). CFTR channel opening by ATP‐driven tight dimerization of its nucleotide‐binding domains. Nature 433, 876–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright CE, Elborn JS, Ramsey BW, Marigowda G, Huang X, Cipolli M, Colombo C, Davies JC, De Boeck K, Flume PA, Konstan MW, McColley SA, McCoy K, McKone EF, Munck A, Ratjen F, Rowe SM, Waltz D, Boyle MP, Group TS & Group TS (2015). Lumacaftor‐Ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for Phe508del CFTR. N Engl J Med 373, 220–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MJ & Smith AE (1993). Molecular mechanisms of CFTR chloride channel dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. Cell 73, 1251–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilschanski M, Zielenski J, Markiewicz D, Tsui LC, Corey M, Levison H & Durie PR (1995). Correlation of sweat chloride concentration with classes of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene mutations. J Pediatr 127, 705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh HI, Yeh JT & Hwang TC (2015). Modulation of CFTR gating by permeant ions. J Gen Physiol 145, 47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JJ, Fatehi M & Linsdell P (2008). Identification of positive charges situated at the outer mouth of the CFTR chloride channel pore. Pflugers Arch 457, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Hu S & Hwang TC (2001). Voltage‐dependent flickery block of an open cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel pore. J Physiol 532, 435–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Wang X, Li M, Sohma Y, Zou X & Hwang TC (2005). High affinity ATP/ADP analogues as new tools for studying CFTR gating. J Physiol 569, 447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Wang X, Liu HY, Zou X, Li M & Hwang TC (2006). The two ATP binding sites of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) play distinct roles in gating kinetics and energetics. J Gen Physiol 128, 413–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielenski J & Tsui LC (1995). Cystic fibrosis: genotypic and phenotypic variations. Annu Rev Genet 29, 777–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]