Abstract

Background and Purpose

The D1CT‐7 mouse is one of the best known animal models of Tourette syndrome (TS), featuring spontaneous tic‐like behaviours sensitive to standard TS therapies; these characteristics ensure a high face and predictive validity of this model, yet its construct validity remains elusive. To address this issue, we studied the responses of D1CT‐7 mice to two critical components of TS pathophysiology: the exacerbation of tic‐like behaviours in response to stress and the presence of sensorimotor gating deficits, which are thought to reflect the perceptual alterations causing the tics.

Experimental Approach

D1CT‐7 and wild‐type (WT) littermates were subjected to a 20 min session of spatial confinement (SC) within an inescapable, 10 cm wide cylindrical enclosure. Changes in plasma corticosterone levels, tic‐like behaviours and other spontaneous responses were measured. SC‐exposed mice were also tested for the prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the startle response (a sensorimotor gating index) and other TS‐related behaviours, including open‐field locomotion, novel object exploration and social interaction and compared with non‐confined counterparts.

Key Results

SC produced a marked increase in corticosterone concentrations in both D1CT‐7 and WT mice. In D1CT‐7, but not WT mice, SC exacerbated tic‐like and digging behaviours, and triggered PPI deficits and aggressive responses. Conversely, SC did not modify locomotor activity or novel object exploration in D1CT‐7 mice. Both tic‐like behaviours and PPI impairments in SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice were inhibited by standard TS therapies and D1 dopamine receptor antagonism.

Conclusions and Implications

These findings collectively support the translational and construct validity of D1CT‐7 mice with respect to TS.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Updating Neuropathology and Neuropharmacology of Monoaminergic Systems. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v173.13/issuetoc

Abbreviations

- NC

non‐confined

- PPI

prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex

- SC

spatial confinement

- TS

Tourette syndrome

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| α1 adrenoceptor |

| D1 receptor |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by recurrent motor and phonic tics; these sudden, purposeless behaviours are typically executed in response to premonitory sensory phenomena, uncomfortable feelings of fixation or intrusive somatic cues (Scahill et al., 1995; Cohen et al., 2013). Several authors have posited that the roots of sensory phenomena in TS may lie in dysfunctions of sensorimotor gating (Swerdlow and Sutherland, 2006), the process aimed at filtering out irrelevant or redundant information (Braff et al., 2001); accordingly, TS patients exhibit deficits in the prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle reflex (Castellanos et al., 1996; Swerdlow et al., 2001), the best characterized operational measure of sensorimotor gating. The importance of perceptual alterations in TS pathophysiology is also indicated by the robust influence of environmental conditions on symptom severity; in particular, both sensory phenomena and tics are exacerbated by stress (Robertson, 2000; Jankovic, 2001; Conelea and Woods, 2008; Cohen et al., 2013).

The pharmacological management of TS is mainly based on antipsychotic drugs (Jiménez‐Jiménez and García‐Ruiz, 2001), which block dopamine receptors, as well as the α2 adrenoceptor agonist clonidine, which reduces the cortical release of noradrenaline by activating autoreceptors (Cohen et al., 1979). These therapies, however, have inconsistent efficacy, and often lead to serious side effects that can reduce quality of life and therapeutic compliance of TS patients (Silva et al., 1996).

Animal models of TS are essential tools for the development of novel therapies with better efficacy and tolerability profiles (Godar et al., 2014). One of the best characterized animal models of TS is D1CT‐7 mice, a transgenic line generated through the attachment of a neuropotentiating cholera toxin to the D1 receptor promoter; these animals display tic‐like manifestations that are reduced by antipsychotic drugs and clonidine (Campbell et al., 1999a; Nordstrom and Burton, 2002). Although these characteristics confer high face and predictive validity for TS to D1CT‐7 mice, their construct validity remains poorly understood.

To explore this critical issue, the present study was designed to assess the sensorimotor gating and stress susceptibility of D1CT‐7 mice, given the importance of these phenomena in the pathophysiology of TS. In particular, we examined the behavioural responses of D1CT‐7 and wild‐type (WT) littermates subjected to a naturalistic environmental stressor, consisting of a 20 min spatial confinement (SC) within a cylindrical enclosure placed in their home cages (Figure 1A). The advantage of SC over other common modalities of experimental stress (such as foot shock or restraint) is that it does not lead to marked anxiety‐like behaviours, which may mask or interfere with tic‐like responses or other spontaneous behaviours.

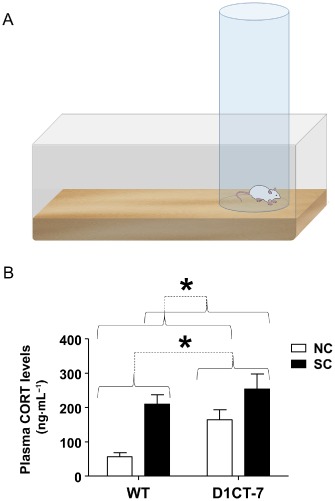

Figure 1.

Effect of SC on plasma corticosterone. (A) Graphical representation of the experimental setting used for SC. (B) Effects of SC on corticosterone levels. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for comparisons indicated by dotted lines. Curvy brackets are used to indicate main effects. n = 8 per group. For more details, see text.

Methods

Animal welfare and ethical statement

We used 3‐ to 4‐month‐old, experimentally naïve male Balb/c mice weighing 20–30 g. Animals were purchased by Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and bred and genotyped as reported by Campbell et al. (1999a). Because the pattern of inheritance of D1CT‐7 mice is autosomal dominant, WT females were bred with heterozygous D1CT‐7 sires; this breeding scheme was selected to standardize maternal behaviour. Animals were housed in group cages with ad libitum access to food and water. The room was maintained at 22°C, on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle from 0800 to 2000 h. Animals were tested during their light cycle between 1200 and 1600 h to minimize any potential circadian effects. All experimental procedures were in compliance with the National Institute of Health guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Use Committee of the University of Kansas. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Experimental design

The first experiment (n = 8 per group) was carried out to validate the stressful effects of SC, by testing plasma corticosterone levels at the end of the 20 min manipulation, as compared with non‐confined (NC) counterparts. We then tested the effects of SC on spontaneous behaviours of D1CT‐7 and WT mice (n = 8 per group), with a particular focus on tic‐like manifestations and repetitive digging responses. The third, fourth, fifth and sixth studies were performed to verify the effects of SC exposure on startle and PPI, locomotor behaviour, novel object exploration and social interaction respectively. All experiments were performed with groups of eight mice per genotype, with the exception of the assessment of the correlation between startle parameters and tic‐like behaviours, which was conducted with 15 SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice to confer sufficient statistical power for regression analyses. The final series of experiments was performed to test the efficacy of haloperidol, clonidine and SCH23390 on tic‐like behaviours and PPI deficits in D1CT‐7 mice. These experiments were conducted with 12 mice per group for each pharmacological assessment.

All experiments were conducted by trained observers unaware of the treatments using a randomized design for treatment assignment. Mice were not used for more than one experiment to avoid stress carry‐over effects. The numbers of animals for each test were based on preliminary power analyses based on pilot studies.

SC

Animals were confined within a clear, bottomless Plexiglas cylinder (10 cm in diameter × 30 cm in height), which was placed in their home cages, deeply embedded in bedding to ensure stability. A schematization of this experimental setting is provided in Figure 1. SC lasted 20 min, and behaviours were video‐recorded for the last 10 min so as to allow animals to avoid potential behavioural alterations caused by neophobia induced by the exposure to the unfamiliar enclosure. Tic‐like manifestations as well as digging responses were scored by trained observers blinded to the genotype and treatment. Tic‐like manifestations were defined as rapid (<1 s) twitches of the head and/or body. Observations were obtained by trained observers, blinded to the genotype and treatment, as previously indicated (Nordstrom and Burton, 2002). For each experiment, one cohort was subjected to 20 min SC prior to behavioural testing. Another cohort consisting of NC control mice remained in their home cages. In order to avoid potential carry‐over effects of SC stress, each animal was used only once in our experimental design.

Corticosterone measurements

Animals were exposed to SC or NC conditions for 20 min between 1200 and 1600 h, then rapidly killed via decapitation. Trunk blood was collected at 1200 and 1600 h. Serum corticosterone was measured in triplicate using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Intra‐assay precision and inter‐assay precision was calculated as 4.6 and 8.3% respectively. Limit of detection was determined as 16.9 pg·mL−1.

Acoustic startle reflex and PPI

Startle testing was conducted as previously described (Frau et al., 2013). Briefly, the apparatus used for detection of startle reflexes (SR‐LAB; San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) consisted of five Plexiglas cages (diameter: 5 cm) in sound‐attenuated chambers with fan ventilation. Each cage was mounted on a piezoelectric accelerometric platform connected to an analogue digital converter. The response to each stimulus was recorded as 65 consecutive 1 ms readings. A dynamic calibration system was used to ensure comparable sensitivities across chambers. The startle testing protocol featured a 70 dB background white noise, and consisted of a 5 min acclimatization period, followed by three consecutive blocks of pulse, prepulse + pulse and ‘no stimulus’ trials. During the first and the third block, mice received only five pulse‐alone trials of 115 dB. Conversely, in the second block mice were exposed to a pseudorandom sequence of 50 trials, consisting of 12 pulse‐alone trials, 30 trials of pulse preceded by 73, 76 or 82 dB pre‐pulses intensities (10 for each level of prepulse loudness) and eight no stimulus trials, where only the background noise was delivered. Intertrial intervals were selected randomly between 10 and 15 s. Sound levels were assessed using an A‐scale setting. Percent PPI was calculated with the following formula:

The first five pulse‐alone bursts were excluded from the calculation. As no interaction between prepulse levels and treatment was found in the statistical analysis, %PPI values were collapsed across prepulse intensity to represent average %PPI.

Open‐field locomotor behaviour

Spontaneous locomotor behaviours to novel environments were tested for 60 min in a square force plate actometer (side: 42 cm; height: 30 cm) as previously described (Fowler et al., 2001). Each force plate actometer consisted of four force transducers placed at the corners of each load plate. Transducers were sampled 100 times s−1, yielding a 0.01 s temporal resolution, a 0.2 g force resolution and a 2 mm spatial resolution. Custom software directed the timing and data‐logging processes via a LabMaster interface (Scientific Solutions Inc., Mentor, OH, USA). Additional algorithms were used to extract macrobehavioural variables, such as distance travelled, number of low‐mobility bouts etc. Distance travelled was calculated as the sum of the distances between coordinates of the location of centre of force recorded every 0.50 s over the recording session. Low‐mobility bouts were defined as periods of 5 s during which mice confined their movements to a 15 mm radius virtual circle. Time spent in the centre was measured in a central quadrant (side: 21 cm) over the first 5 min block. Rotation bias was calculated by summing the locomotor turn direction over time using the centre of the actometer floor as a reference point. Wall leaps were identified based on specific force–time waveform (required to have minimum force below −90% of body weight for 0.03 s or longer, and at no more than 3 cm from the wall), using custom scrolling graphics software.

Novel object exploration

Novel exploration was measured by placing foreign objects in the animal's home cage for 15 min as previously described (Godar et al., 2011). The number and duration of exploratory approaches towards the objects were scored from video recordings and quantified. Exploratory activity was defined as sniffing or touching the objects with the snout, but not climbing or sitting on the objects.

Social interaction

Social behaviours were tested for 10 min in an unfamiliar cage and video recorded as previously described (Bortolato et al., 2012). Behavioural measures consisted of the number and duration of interactions towards foreign age‐ and weight‐matched male Balb/c WT conspecifics, as well as the number and duration of fighting behaviours (attacks and fighting episodes). Care was taken in differentiating fighting episodes from compulsive biting or allogrooming in D1CT‐7 mice, which have been shown to result in occasional harm to cage mates. Social interaction was defined as sniffing or touching the conspecific with the snout.

Statistical analyses

Normality and homoscedasticity of data distribution were verified using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Bartlett's tests. Statistical analyses of parametric data were performed with one‐way or two‐way anovas, followed by Newman–Keuls' test for post hoc comparisons. Locomotor behaviours were analysed using a two‐way anova design for repeated measures with genotype, condition and time as the factors. Correlations were performed between tic‐like outbursts and PPI, as well as between tics and startle amplitude by means of linear regression analyses. Significance threshold was set at 0.05.

Drugs

The following drugs were used: clonidine and SCH23390 (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were dissolved in saline. Haloperidol (Sigma‐Aldrich) was dissolved in a single drop of 1 M HCl and diluted with saline. The doses of each drugs were selected so as to yield ≥80% occupancy of their targeted receptors (Haraguchi et al., 1997; Tan et al., 2002) without reducing spontaneous activity in the SC paradigm (as verified in pilot studies). Different cohorts of animals were used for each drug treatment group. The nomenclature of all receptors and drug targets mentioned in this article conforms to the guidelines indicated in British Journal of Pharmacology's Concise Guide to Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2013).

Results

SC increases corticosterone levels

The efficacy of SC as a stressor was verified in WT and D1CT‐7 mice by testing the changes in plasma corticosterone levels induced by this manipulation. A two‐way anova revealed that SC induced a marked increase in corticosterone concentrations in both genotypes (main effect of SC); furthermore, D1CT‐7 mice displayed higher corticosterone levels than WT, irrespective of the environmental conditions (main effect of genotype) (Figure 1B). Nevertheless, no significant interactions between SC and genotype were found.

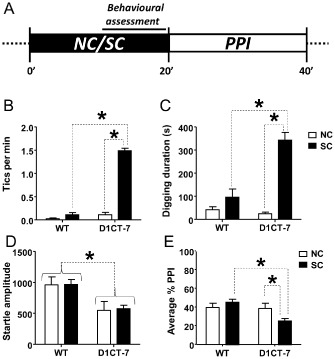

SC enhances tic‐like responses and digging in D1CT‐7 mice

We then tested the behaviours of D1CT‐7 and WT littermates in response to SC, as compared with NC counterparts kept in their home cages. In D1CT‐7 mice, SC induced a dramatic increase in tic‐like responses (Figure 2B) and digging behaviour (Figure 2C). In contrast, SC did not significantly alter the behaviours of WT mice. Furthermore, tic‐like and digging behaviours in SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice were significantly greater than those observed in SC WT controls. These data suggest that this SC elicits a pronounced enhancement of TS‐related behaviours in D1CT‐7, but does not significantly affect WT mice.

Figure 2.

SC elicits a robust increase in tic‐like behaviour, repetitive digging behaviour and deficits in PPI in D1CT‐7, but not WT mice. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Effects of SC on tic‐like responses. (C) Effects of SC on repetitive digging. (D) Effects of SC on startle amplitude. (E) Effects of SC on PPI of the startle. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for comparisons indicated by dotted lines. Curvy brackets are used to indicate main effects. n = 8 per group. For details, see text.

D1CT‐7 mice exhibit sensorimotor gating deficits following SC

In a separate experiment, we investigated whether SC exposure led to alterations in sensorimotor gating, as assessed through the PPI of the acoustic startle. D1CT‐7 mice exhibited a reduction in startle amplitude (Figure 2D), irrespective of exposure to SC. Furthermore, SC exposure elicited a significant reduction in PPI (Figure 2E) in D1CT‐7, but not WT mice. Linear regression analyses revealed that the number of tic‐like behaviours was not correlated with either startle amplitude [F(1,14) = 1.19; NS; R 2 = 0.08] or %PPI values [F(1,14) = 2.69; NS; R 2 = 0.16] (data not shown).

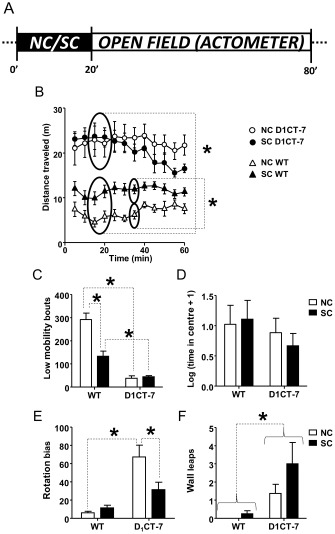

SC exposure does not affect hyperactivity in D1CT‐7 mice in a novel open field

Next, we investigated whether SC exposure can alter other behavioural parameters related to TS symptoms. Accordingly, we tested the locomotor responses in SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 and WT mice using a novel open field on a force–plate actometer. Three‐way anova (with genotype, environmental condition and time as factors) revealed that D1CT‐7 mice exhibited a hyperactive phenotype compared with WT mice (Figure 3B). Furthermore, SC was found to increase overall locomotor activity. Conversely, no significant time‐dependent differences were found. A significant genotype × condition interaction was also detected, and post hoc analyses revealed that SC significantly increased locomotor behaviour in WT mice, but failed to affect the hyperlocomotion of D1CT‐7 mice. The analysis of low‐mobility bouts (Figure 3C) revealed significant main effects for genotype and condition, as well as their interaction. Post hoc comparisons showed that D1CT‐7 animals engaged in fewer low‐mobility bouts than WT mice pre‐exposed to the same conditions. In addition, SC‐exposed WT mice showed fewer low‐mobility bouts than NC‐exposed WT counterparts; however, no differences were detected in the time spent in the centre (Figure 3D). NC D1CT‐7 mice were also found to display a significantly higher rotation bias than both NC WT and SC D1CT‐7 mice (Figure 3E). D1CT‐7 mice also exhibited a genotype‐specific increase in the number of wall leaps (Figure 3F) compared with WT counterparts.

Figure 3.

D1CT‐7 mice exhibit open‐field locomotor hyperactivity regardless of SC. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Effects of SC exposure on locomotor activity of D1CT‐7 and WT mice. (C) Effects of SC exposure on low‐mobility bouts. (D) Effects of SC exposure on rotation bias. (E) Effects of SC exposure on wall leap behaviour. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for comparisons indicated by dotted lines. Curvy brackets are used to indicate main effects. n = 8 per group. For details, see text.

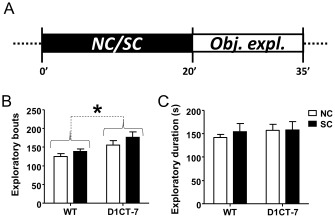

SC does not affect novel object exploration in D1CT‐7 mice

We next examined whether SC evoked anxiety‐related behaviours towards novel objects. D1CT‐7 mice exhibited an increase in novel object exploratory approaches (Figure 4B), but no differences were detected for condition (i.e. SC vs. NC) or genotype × condition interactions. Two‐way anova analyses of exploratory duration (Figure 4C) revealed no significant effects of genotype, condition or their interaction.

Figure 4.

D1CT‐7 mice show increased exploratory approaches towards novel objects. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Effects of SC exposure on the number of exploratory approaches. (C) Effects of SC exposure on total exploratory duration. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for comparisons indicated by dotted lines. Curvy brackets are used to indicate main effects. n = 8 per group. For details, see text.

SC increases aggressive behaviour in D1CT‐7 mice

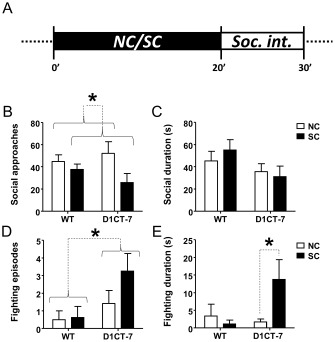

To determine whether SC modified behavioural responses to foreign conspecifics, animals were tested in the social interaction paradigm. We found that social exploratory approaches were significantly reduced following SC (Figure 5B), irrespective of the genotype. The duration of the social interaction was equivalent among all groups (Figure 5C). Notably, D1CT‐7 mice exhibited a higher number of aggressive episodes during social encounters compared with their WT counterparts (Figure 5D), but no differences were detected for condition or genotype × condition. SC exposure increased aggressive behaviours in D1CT‐7 mice, but not in WT animals. (Figure 5E). Notably, fighting behaviours were characterized by defensive postures (such as tail rattling) and typical aggressive manifestations, and were clearly distinct from harmful tic‐like manifestations, such as compulsive biting and exaggerated allogrooming.

Figure 5.

SC increases aggression in D1CT‐7 mice in the social interaction paradigm. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Effects of SC exposure on the number of social approaches. (C) Effects of SC exposure on total duration of social interaction. (D) Effects of SC exposure on number of fighting episodes. (E) Effects of SC exposure on total fighting duration. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for comparisons indicated by dotted lines. Curvy brackets are used to indicate main effects. n = 8 per group. For details, see text.

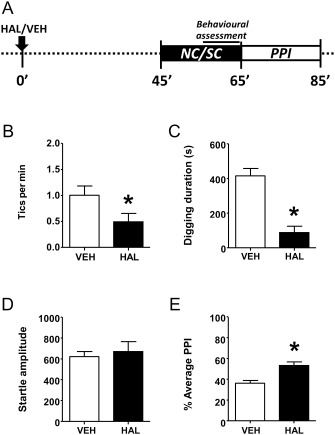

Tic‐like behaviours and PPI deficits in D1CT‐7 mice are sensitive to haloperidol, clonidine and SCH23390

Because D1CT‐7, but not WT mice, exhibited tic‐related behaviours and PPI deficits and only following exposure to SC, we limited our pharmacological testing to this group in order to avoid potential floor effects. Next, we tested the predictive validity of D1CT‐7 mutants as animal models of TS by evaluating the effect of standard anti‐tic agents on the number of tic‐like behaviours (during SC) and sensorimotor gating disruptions (following SC). Haloperidol (0.3 mg·kg−1, i.p., injected 45 min before testing) elicited a reduction in the number of tic‐related manifestations (Figure 6B) and reduced digging activity (Figure 6C) in D1CT‐7 mice. Although haloperidol attenuated PPI disruptions (Figure 6E), it did not affect overall startle amplitude (Figure 6D) or latency to peak startle (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Haloperidol (HAL; 0.3 mg·kg−1, i.p.) reduced repetitive (perseverative) and tic‐like behaviours, as well as PPI deficits in D1CT‐7 mice exposed to SC. (A) Timeline of treatments and experiments. (B) Effects of HAL on tic‐like responses. (C) Effects of HAL on perseverative digging. (D) Effects of HAL on startle amplitude. (E) Effects of HAL on PPI. All data refer to SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle (VEH). n = 12 per group. For more details, see text.

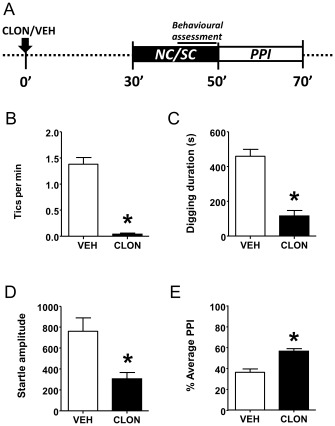

Similar to haloperidol, clonidine (0.2 mg·kg−1, i.p., administered 30 min before testing) decreased the expression of tic‐like behaviours (Figure 7B) and digging activity (Figure 7C). Clonidine also significantly reduced startle amplitude (Figure 7D) and countered PPI disruptions (Figure 7E), but did not affect latency to peak startle (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Clonidine (CLON; 0.2 mg·kg−1, i.p.) reduced repetitive (perseverative) and tic‐like behaviours, as well as PPI deficits in D1CT‐7 mice exposed to SC. (A) Timeline of treatments and experiments. (B) Effects of CLON on tic‐like responses. (C) Effects of CLON on perseverative digging. (D) Effects of CLON on startle amplitude. (E) Effects of CLON on PPI. All data refer to SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle (VEH). n = 12 per group. For more details, see text.

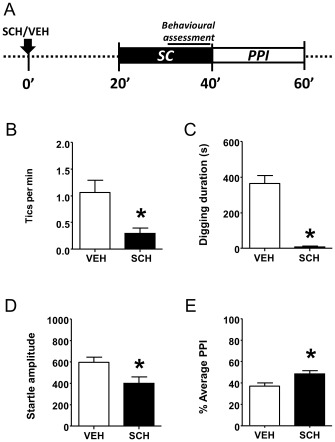

Finally, we examined whether the D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 (1 mg·kg−1, s.c., injected 20 min before testing) prevented the TS‐related features in SC D1CT‐7 mice. We found that D1 receptor blockade decreased tic‐like behaviours (Figure 8B) and digging (Figure 8C) during SC; furthermore, SCH23390 reduced startle amplitude (Figure 8D) and restored PPI (Figure 8E) following SC. In contrast, no differences were observed in the latency to peak startle (data not shown).

Figure 8.

The D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 (SCH; 1 mg·kg−1, s.c.) reduced repetitive (perseverative) and tic‐like behaviours, as well as PPI deficits in D1CT‐7 mice exposed to SC. (A) Timeline of treatments and experiments. (B) Effects of SCH on tic‐like responses. (C) Effects of SCH on perseverative digging. (D) Effects of SCH on startle amplitude. (E) Effects of SCH on PPI. All data refer to SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice. Data are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle (VEH). n = 12 per group. For more details, see text.

Discussion

The results of the present study show that the environmental stress caused by SC, triggered a number of TS‐related phenotypes in D1CT‐7, but not WT mice, including a robust exacerbation of tic‐like and repetitive responses, as well as PPI deficits and aggressive behaviours. These effects are in line with previous reports documenting exacerbation of leaping and climbing compulsions in D1CT‐7 mice exposed to predator urine odour (McGrath et al., 1999). We also found that SC‐induced tic‐like responses and PPI deficits were significantly inhibited by standard TS therapies, such as the antipsychotic haloperidol and clonidine, as well as the D1 dopamine receptor antagonist SCH23390. Although D1CT‐7 mice displayed lower startle amplitude than their WT littermates, this parameter was not affected by SC, suggesting that the observed reduction of %PPI did not result from computational artefacts.

As mentioned earlier, the exacerbation of tic behaviour in response to stress and PPI deficits are essential elements of TS pathophysiology (Castellanos et al., 1996; Robertson, 2000; Swerdlow et al., 2001), which are posited to reflect perceptual and information‐processing alterations. In particular, PPI deficits have therefore been highlighted as key parameters to assess construct validity of animal models of TS (Swerdlow and Sutherland, 2006; Godar et al., 2014). Based on this background, our findings collectively support the construct validity of this TS model. The pathophysiological relevance of D1CT‐7 transgenic mice to TS symptoms is also supported by the recent discovery that TS patients display hyperactivity of the same sensorimotor circuit that is neuropotentiated in these mice (Campbell et al., 1999a; Bohlhalter et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2011; Church and Schlaggar, 2014); furthermore, it is worth noting that recent data indicated that in rodents the optogenetic stimulation of the cortex has been shown to produce features similar to symptoms of OCD – a highly co‐morbid syndrome with TS (Ahmari et al., 2013).

There is ample evidence showing that behavioural stereotypes are a common sign of discomfort in animals subjected to prolonged SC (Cole et al., 1990; Wemelsfelder, 1990; Garner and Mason, 2002; Lutz et al., 2003). The responsiveness of D1CT‐7 mice to short‐term SC may signify their high sensitivity to the spatial restriction and low contextual stimulation imposed by this manipulation, which contrast with the environmental requirements for their high spontaneous locomotor and exploratory activity. In addition, the higher plasma levels of corticosterone in D1CT‐7 mice subjected to baseline conditions suggest that these mice display an intrinsically elevated stress response. The results of our experiments suggest that the summation of the baseline stress levels of D1CT‐7 mice and the effect of SC may lead these animals to reach a critical threshold of activation, which may trigger the exacerbation of tic‐like behaviours and the reduction in PPI. Irrespective of this issue, future studies are warranted to explore the basis of the higher baseline corticosterone plasma levels in D1CT‐7 mice.

The fact that tic‐like behaviours and PPI deficits were prevented by the modulation of dopamine and noradrenaline receptors suggests that the effects of SC in D1CT‐7 mice are probably caused by an enhanced catecholamine release in critical areas of the cortico‐striatal‐thalamo‐cortical (CSTC) circuit, which is the anatomical substrate of TS pathophysiology, stereotyped behaviours and PPI regulation (Swerdlow et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2011; Singer, 2013). Accordingly, acute stress has been shown to stimulate dopamine and noradrenaline release in the striatum and in the prefrontal cortex, (Abercrombie et al., 1989; Finlay et al., 1995). Further microdialysis studies are needed to evaluate the variations in dopamine and noradrenaline release during SC in D1CT‐7 and WT mice.

In baseline conditions, D1CT‐7 mice were shown to express the transcript of their neuropotentiating transgene in a subset of D1 receptor‐containing neurons, including glutamatergic pyramidal projection neurons in somatosensory and piriform cortex as well as GABAergic interneurons in the intercalated nucleus of the amygdala (Campbell et al., 1999a). Although the somatosensory cortical areas potentiated in the mice similarly hyperactivate to trigger premonitory urges in human TS, to the best of our knowledge these regions have not been directly implicated in the regulation of PPI. Thus, the observed sensorimotor deficits in D1CT‐7 mutants may be due to the effect of potentiated glutamatergic projections from these regions to limbic circuits. Given that the elevation of the transgene's cAMP in the CT potentiates the responsiveness of neurons to their own endogenous excitatory neurotransmitters (Campbell et al., 1999a), it is possible that these neuropotentiated cortical and amygdala neurons in the D1CT‐7 mice may respond to stress‐triggered endogenous fast‐acting neurotransmitter input by subsequently ‘stepping up’ their own neurotransmitter output, which could aggravate any baseline, sub‐threshold symptoms. In this respect, it is worth noting that the increase in glucocorticoids produced by acute stress has been shown to enhance glutamate release from the cortex and amygdala (Popoli et al., 2011), highlighting the possibility that changes in corticolimbic glutamate output may participate in the effects of SC in these animals.

Alternatively, SC may affect the expression of the D1 receptor‐associated neuropotentiating effect in CSTC areas; indeed, previous studies have shown that acute stress elicits rapid changes in the expression and transcription of dopaminergic genes (Sabban and Kvetnanský, 2001). Thus, it is possible that SC may lead to the expression of the D1CT‐7 construct in areas of the CSTC circuits, which may remain undetected under baseline conditions. Future studies are warranted to examine the effects of SC on neurochemical changes in CSTC in D1CT‐7 mice.

The effects of SC on tic‐like behaviours and PPI in D1CT‐7 mice were antagonized by haloperidol and clonidine, in line with previous findings on the effectiveness of both drugs at reducing spontaneous tic‐like responses in this context (Nordstrom and Burton, 2002). In addition, the effectiveness of the selective D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 suggests that D1 receptors are involved in the tic‐like behaviours and PPI deficits and is in agreement with previous findings indicating that these molecular targets contribute to both the PPI and stereotyped behaviours in mice (Chartoff et al., 2001; Ralph‐Williams et al., 2003; Frau et al., 2013). D1 receptors play a key role in the processing of informational salience and the enactment of behavioural stereotypies in rodents. For instance, D1 receptor agonists disrupt sensorimotor gating in mice (Ralph‐Williams et al., 2003; Frau et al., 2013) and striatal D1 receptor activation induces locomotor hyperactivity and stereotyped behaviour through the reinforcement of ongoing behaviours (Chartoff et al., 2001; Albin and Mink, 2006). It is worth noting that ecopipam, a selective D1 receptor antagonist, is currently under investigation as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of tics (Gilbert et al., 2014).

In parallel with clinical reports, we did not detect any correlation between the severity of the tic‐like outbursts and PPI deficits in D1CT‐7 mice (Castellanos et al., 1996). Because both tic‐like responses and PPI deficits were triggered by SC and responded to anti‐tic therapies, it is likely that these two parameters may depend on converging, but not identical, anatomical substrates.

Another remarkable effect of SC in D1CT‐7 mice was a significant enhancement in aggressive behaviours towards foreign conspecifics in the social interaction paradigm. These manifestations were characterized by typical aggressive and hostile behaviour, including tail rattling and aggressive chasing of the conspecific, and were clearly distinct from compulsive biting during allogrooming, as previously reported (Campbell et al., 1999a; Nordstrom and Burton, 2002). The observed stress‐induced aggressiveness in a model of TS is in line with clinical reports documenting disruptive behaviours, rage outbursts and anger control problems in TS patients, which are often preceded by stressful feelings of tension similar to sensory phenomena (Stephens and Sandor, 1999; Budman et al., 2003).

In agreement with previous studies, we found that D1CT‐7 mice displayed hyperactive locomotor behaviour (Campbell et al., 1999a), which was demonstrated as fewer low‐mobility bouts and greater distances travelled. The hyperlocomotion displayed by D1CT‐7 mice was paralleled by an increase in the number of approaches, but not overall duration, of exploratory activity directed towards unfamiliar objects. Neither phenomenon was significantly affected by SC; however, this manipulation significantly increased the exploratory activity of WT mice. D1CT‐7 mutants also showed a greater locomotor rotational bias, which probably reflects elevated brain dopamine levels and its tendency to induce repetitive, compulsive behaviour (Campbell et al., 1999a) in this transgenic line. Indeed, rodents treated with indirect‐acting dopamine agonists, such as amphetamine or cocaine also show large rotational biases (Glick et al., 1988; Dews, 1991; Fowler et al., 2001; 2007), which probably signify behavioural stereotypy (Dews, 1991). In accord with previous reports (Campbell et al., 1999a), D1CT‐7 mice displayed more wall leaps than WT mice, a finding consistent with the hypothesis that the D1CT‐7 mice express an increased tendency to engage in repetitive, short‐duration topographically distinct motor behaviour. Notably, rotational bias was strikingly reduced by SC in D1CT‐7 mice; although the specific cause of this phenomenon remains unclear, it is possible that this effect may reflect the higher occurrence of other repetitive behaviours, such as rearing or grooming, which may have partially over‐ridden their locomotor responses.

SC D1CT‐7 mice failed to exhibit open‐field thigmotaxis, a response that has been associated with anxiety‐related responses (Simon et al., 1994). Although this finding may appear counterintuitive, given the increased stress levels in SC D1CT‐7 mice, it should be noted that the extrapolation of anxiety‐related phenomena (and particularly thigmotaxis) in hyperactive mice is generally considered to be unreliable, in view of the high risk of false‐positive and false‐negative findings (Holmes and Crawley, 2000).

Although the SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice exhibited several behavioural features that closely mirror phenotypic traits found in TS patients, several limitations of the study should be recognized. Firstly, our study focused solely on males, in view of the high predominance of TS in this gender. Although males have a higher severity of tic‐like manifestations, mutants of both sexes display these behavioural abnormalities (Nordstrom and Burton, 2002), and further studies on the sex differences in this line are warranted. Secondly, we found that D1CT‐7 mice exhibited fewer spontaneous tic‐like outbursts than previously described (Nordstrom and Burton, 2002) and more sensitivity to the D1 receptor antagonist, SCH23390, than previously described (Campbell et al., 1999b), both of which may be due to a different penetrance of the gene mutation in our colony. Thirdly, the evaluation of the pharmacological effects of haloperidol, clonidine and SCH23390 was only performed in SC‐exposed D1CT‐7 mice, but not in NC counterparts (or in WT controls). This design was made necessary by the small number of D1CT‐7 mice available, in view of their suboptimal reproductive efficiency, which allowed us to obtain no more than 10–12 males per generation (with an equivalent number of breeders), as well as our specific experimental decision of testing each animal only once (in order to avoid potential carry‐over effects). Fourthly, although the effects of all drugs were observed to produce no overt alterations in the activity of the mice, we could not measure the locomotor behaviour in these mice subjected to SC, and therefore cannot fully rule out the possibility that the observed amelioration in tic‐like responses is partially due to subtle changes in locomotion. Finally, in spite of the analogy between SC‐induced behavioural responses and symptoms of TS, our analyses revealed that the D1CT‐7 mutants do exhibit some behavioural responses not directly related to this disorder, such as reduced startle acoustic reflex, and hyperlocomotor activity (although the latter activity can be likened to manifestations of ADHD or perseverative traits in OCD, both conditions that are often co‐morbid with TS).

In spite of these limitations, our findings showing that SC exacerbated the tics and PPI deficits in D1CT‐7 mice, and that these deficits were sensitive to validated therapies for TS, appear to confirm the translational relevance of D1CT‐7 mice as a valuable animal model that may replicate the influence of environmental stress on TS symptoms. Future studies are needed to elucidate the specific neurobiological changes induced by SC in this model, and their role in the symptoms of TS.

Author contributions

S. C. G., S. C. F. and M. B. designed the research study and wrote the manuscript. S. C. G., L. J. M., S. C. F. and M. B. analysed the data. S. C. G., L. J. M., H. J. S., C. M. J. and A. M. G. conducted the experiments.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Institute of Health grant R01 MH104603‐01 (to M. B.), the research grant from the Tourette Syndrome Association (to M. B.) and the University of Kansas Strategic Initiatives Grant. This study was also partially supported by sub‐awards (to M. B.) from the NIH grants P20 GM103638, UL1 TR000001 (formerly UL1RR033179), as well as K‐INBRE undergraduate fellowships (to H. J. S. and C. M. J.), supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20 GM103418) awarded to the University of Kansas and University of Kansas Medical Center. The authors are indebted to the EU COST Action CM1103 ‘Structure‐based drug design for diagnosis and treatment of neurological diseases: dissecting and modulating complex function in the monoaminergic systems of the brain’ for supporting their international collaboration. We are grateful to Frank Burton for his generous help with establishing the D1CT‐7 animal colony and assistance in conducting the experiments. We are also grateful to Lindsay Leonard for her valuable support in the execution of the experiments.

Godar, S. C. , Mosher, L. J. , Strathman, H. J. , Gochi, A. M. , Jones, C. M. , Fowler, S. C. , and Bortolato, M. (2016) The D1CT‐7 mouse model of Tourette syndrome displays sensorimotor gating deficits in response to spatial confinement. Br J Pharmacol, 173: 2111–2121. doi: 10.1111/bph.13243.

References

- Abercrombie ED, Keefe KA, DiFrischia DS, Zigmond MJ (1989). Differential effect of stress on in vivo dopamine release in striatum, nucleus accumbens, and medial frontal cortex. J Neurochem 52: 1655–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmari SE, Spellman T, Douglass NL, Kheirbek MA, Simpson HB, Deisseroth K et al (2013). Repeated cortico‐striatal stimulation generates persistent OCD‐like behavior. Science 340: 1234–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Mink JW (2006). Recent advances in Tourette syndrome research. Trends Neurosci 29: 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013). The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1459–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlhalter S, Goldfine A, Matteson S, Garraux G, Hanakawa T, Kansaku K et al (2006). Neural correlates of tic generation in Tourette syndrome: an event‐related functional MRI study. Brain 129: 2029–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M, Godar SC, Melis M, Soggiu A, Roncada P, Casu A et al (2012). NMDARs mediate the role of monoamine oxidase A in pathological aggression. J Neurosci 32: 8574–8582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NC (2001). Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 156: 234–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budman CL, Rockmore L, Stokes J, Sossin M (2003). Clinical phenomenology of episodic rage in children with Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res 55: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KM, de Lecea L, Severynse DM, Caron MG, McGrath MJ, Sparber SB et al (1999a). OCD‐like behaviors caused by a neuropotentiating transgene targeted to cortical and limbic D1+ neurons. J Neurosci 19: 5044–5053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KM, McGrath MJ, Burton FH (1999b). Differential response of cortical‐limbic neuropotentiated compulsive mice to D1 and D2 antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol 371: 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Fine EJ, Kaysen D, Marsh WL, Rapoport JL, Hallett M (1996). Sensorimotor gating in boys with Tourette's syndrome and ADHD: preliminary results. Biol Psychiatry 39: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartoff EH, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Dorsa DM, Palmiter RD (2001). Induction of stereotypy in dopamine‐deficient mice requires striatal D1 receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10451–10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church JA, Schlaggar BL (2014). Pediatric Tourette syndrome: insights from recent neuroimaging studies. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 3: 386–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Young JG, Nathanson JA, Shaywitz BA (1979). Clonidine in Tourette's syndrome. Lancet 2: 551–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SC, Leckman JF, Bloch MH (2013). Clinical assessment of Tourette syndrome and tic disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37: 997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole BJ, Cador M, Stinus L, Rivier J, Vale W, Koob GF et al (1990). Central administration of a CRF antagonist blocks the development of stress‐induced behavioral sensitization. Brain Res 512: 343–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conelea CA, Woods DW (2008). The influence of contextual factors on tic expression in Tourette's syndrome: a review. J Psychosom Res 65: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews PB (1991). Stereotypy and asymmetry in mice. J Neural Transm Suppl 34: 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay JM, Zigmond MJ, Abercrombie ED (1995). Increased dopamine and norepinephrine release in medial prefrontal cortex induced by acute and chronic stress: effects of diazepam. Neuroscience 64: 619–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SC, Birkestrand BR, Chen R, Moss SJ, Vorontsova E, Wang G et al (2001). A force‐plate actometer for quantitating rodent behaviors: illustrative data on locomotion, rotation, spatial patterning, stereotypies, and tremor. J Neurosci Methods 107: 107–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SC, Covington HE 3rd, Miczek KA (2007). Stereotyped and complex motor routines expressed during cocaine self‐administration: results from a 24‐h binge of unlimited cocaine access in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 192: 465–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frau R, Pillolla G, Bini V, Tambaro S, Devoto P, Bortolato M (2013). Inhibition of 5alpha‐reductase attenuates behavioral effects of D1‐, but not D2‐like receptor agonists in C57BL/6 mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 542–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner JP, Mason GJ (2002). Evidence for a relationship between cage stereotypies and behavioural disinhibition in laboratory rodents. Behav Brain Res 136: 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DL, Budman CL, Singer HS, Kurlan R, Chipkin RE (2014). A D1 receptor antagonist, ecopipam, for treatment of tics in Tourette syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol 37: 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Carlson JN, Baird JL, Maisonneuve IM, Bullock AE (1988). Basal and amphetamine‐induced asymmetries in striatal dopamine release and metabolism: bilateral in vivo microdialysis in normal rats. Brain Res 473: 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godar SC, Bortolato M, Frau R, Dousti M, Chen K, Shih JC (2011). Maladaptive defensive behaviours in monoamine oxidase A‐deficient mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 14: 1195–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godar SC, Mosher LJ, Di Giovanni G, Bortolato M (2014). Animal models of tic disorders: a translational perspective. J Neurosci Methods 238: 54–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi K, Ito K, Kotaki H, Sawada Y, Iga T (1997). Prediction of drug‐induced catalepsy based on dopamine D1, D2, and muscarinic acetylcholine receptor occupancies. Drug Metab Dispos 25: 675–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Crawley JN (2000). Prombehaviours and limitations of transgenic and knockout mice in modeling psychiatric symptoms In: Myslobodsky MS, Weiner I. (eds). Contemporary Issues in Modeling Psychopathology. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic J (2001). Tourette's syndrome. N Engl J Med 345: 1184–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez‐Jiménez FJ, García‐Ruiz PJ (2001). Pharmacological options for the treatment of Tourette's disorder. Drugs 61: 2207–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz C, Well A, Novak M (2003). Stereotypic and self‐injurious behavior in rhesus macaques: a survey and retrospective analysis of environment and early experience. Am J Primatol 60: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath MJ, Campbell KM, Burton FH (1999). The role of cognitive and affective processing in a transgenic mouse model of cortical‐limbic neuropotentiated compulsive behavior. Behav Neurosci 113: 1249–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C (2010). Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1573–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom EJ, Burton FH (2002). A transgenic model of comorbid Tourette's syndrome and obsessive‐compulsive disorder circuitry. Mol Psychiatry 7: 617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP et al; NC‐IUPHAR (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res 42 (Database Issue): D1098–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoli M, Yan Z, McEwen BS, Sanacora G (2011). The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci 13: 22–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph‐Williams RJ, Lehmann‐Masten V, Geyer MA (2003). Dopamine D1 rather than D2 receptor agonists disrupt prepulse inhibition of startle in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MM (2000). Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment. Brain 123: 425–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Kvetnanský R (2001). Stress‐triggered activation of gene expression in catecholaminergic systems: dynamics of transcriptional events. Trends Neurosci 24: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill LD, Leckman JF, Marek KL (1995). Sensory phenomena in Tourette's syndrome. Adv Neurol 65: 273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RR, Munoz DM, Daniel W, Barickman J, Friedhoff AJ (1996). Causes of haloperidol discontinuation in patients with Tourette's disorder management and alternatives. J Clin Psychiatry 57: 129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P, Dupuis R, Costentin J (1994). Thigmotaxis as an index of anxiety in mice. Influence of dopaminergic transmissions. Behav Brain Res 61: 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer HS (2013). Motor control, habits, complex motor stereotypies, and Tourette syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1304: 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RJ, Sandor P (1999). Aggressive behaviour in children with Tourette syndrome and comorbid attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry 44: 1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NC, Sutherland AN (2006). Preclinical models relevant to Tourette syndrome. Adv Neurol 99: 69–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NC, Karban B, Ploum Y, Sharp R, Geyer MA, Eastvold A (2001). Tactile prepuff inhibition of startle in children with Tourette's syndrome: in search of an ‘fMRI‐friendly’ startle paradigm. Biol Psychiatry 50: 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CM, Wilson MH, MacMillan LB, Kobilka BK, Limbird LE (2002). Heterozygous alpha 2A‐adrenergic receptor mice unveil unique therapeutic benefits of partial agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 12471–12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Maia TV, Marsh R, Colibazzi T, Gerber A, Peterson BS (2011). The neural circuits that generate tics in Tourette's syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 168: 1326–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wemelsfelder F (1990). Boredom and laboratory animal welfare In: Rollin BE. (ed.). The Experimental Animal in Biomedical Research. CRC‐Press: Boca Raton, FL, pp. 243–269. [Google Scholar]