Abstract

Vaccination against pertussis has reduced the disease burden dramatically, but the most severe cases and almost all fatalities occur in infants too young to be vaccinated. Recent epidemiologic evidence suggests that targeted vaccination of mothers during pregnancy can reduce pertussis incidence in their infants. To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of antepartum maternal vaccination in the United States, we created an age-stratified transmission model, incorporating empirical data on US contact patterns and explicitly modeling parent-infant exposure. Antepartum maternal vaccination incurs costs of $114,000 (95% prediction interval: 82,000, 183,000) per quality-adjusted life-year, in comparison with the strategy of no adult vaccination, and is cost-effective in the United States according to World Health Organization criteria. By contrast, vaccinating a second parent is not cost-effective, and vaccination of either parent postpartum is strongly dominated by antepartum maternal vaccination. Nonetheless, postpartum vaccination of mothers who were not vaccinated antepartum improves upon the current recommendation of untargeted adult vaccination. Additionally, the temporary direct protection of the infant due to maternal antibody transfer has efficacy for infants comparable to that conferred to toddlers by the full primary vaccination series. Efficient protection against pertussis for infants begins before birth. We highly recommend antepartum vaccination for as many US mothers as possible.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, dynamic transmission model, maternal antibody transfer, maternal immunization, pertussis, social contact patterns, vaccine policy, whooping cough

Pertussis incidence has been steadily rising over the past decade in many developed countries and is responsible for nearly 200,000 deaths annually in children under 5 years of age worldwide (1, 2). Most severe cases of pertussis and nearly all deaths occur in infants too young to have received the first dose of pertussis vaccine, recommended at 2 months (3). At least 35% of infant pertussis cases are acquired from a family member (4, 5).

The US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that women receive adolescent/adult booster vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) antepartum in every pregnancy (6). The ACIP also encourages other principal contacts, such as fathers and siblings, to be vaccinated (6), extending the “cocoon” of indirect protection (3, 7). To further reduce population-level transmission of pertussis, all adults are recommended to replace a single dose of Td, the vaccine against tetanus and diphtheria, with Tdap, which adds a booster against pertussis (6).

A recent observational study in England and Wales found that the risk of infant pertussis is reduced by 91% when the pregnant mother is vaccinated at least 1 week before the birth (8, 9), demonstrating a much higher effectiveness for antepartum vaccination than was assumed previously. There are 2 potential mechanisms of protection: direct protection of the infant, probably through the transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies, which has been demonstrated to occur following vaccination in the third trimester (10–13); or indirect protection, in which infections are reduced in mothers, the primary conduit of pertussis infection to infants (4).

The proportion of protection conferred by each mechanism is not known, but this information is necessary to compare the effectiveness and value provided by antepartum maternal vaccination, postpartum maternal vaccination, and vaccination of other adults. If direct protection is underestimated, maternal vaccination during pregnancy will appear less effective, as in a previous cost-effectiveness analysis which found antepartum vaccination to be expensive in the US context (14). Additionally, the indirect protection of an infant must be considered in a dynamic way, recognizing that preventing the acquisition of infection from 1 parent would still allow an infant to acquire infection through another route. Previous cost-effectiveness analyses of postpartum vaccination have not modeled the risk of infection dynamically (7, 14–17), relying instead on a static risk reduction parameterized from household infection studies (4). This overestimation of the effectiveness of postpartum vaccination and underestimation of the effectiveness of vaccination during pregnancy could dramatically distort the relative public health value of available vaccination policies.

Here we present results from what is, to our knowledge, the first cost-effectiveness analysis of parental vaccination against pertussis to take into account the new, highly informative antepartum effectiveness data, and the first study to separate the direct and indirect effects of maternal vaccination. Our dynamic model was calibrated to 10 years of US pertussis incidence. We explicitly considered the contact patterns that are fundamental to the indirect protection provided by a postpartum vaccination strategy, incorporating empirical information on age-specific contact rates and durations (18, 19). We assessed current ACIP recommendations, evaluating whether maternal vaccination during pregnancy, postpartum maternal vaccination, vaccination of 2 parents, and untargeted vaccination of adults were cost-effective strategies for the prevention of pertussis in infants.

METHODS

We developed a dynamic transmission model calibrated to both US incidence data from 2003–2012 and case-coverage effectiveness data on antepartum maternal vaccination to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis, comparing 1) the status quo of no adult vaccination; 2) untargeted replacement of a tetanus and diphtheria (Td) booster with Tdap for 3 million adults annually; 3) antepartum vaccination of mothers during pregnancy; 4) postpartum vaccination of mothers immediately following childbirth; 5) antepartum vaccination of 2 parents; and 6) postpartum vaccination of 2 parents. The impact of each strategy was simulated over a time horizon of 20 years, starting in 2015, and evaluated from a societal perspective for the United States that accounts for direct medical costs to individuals and insurers and health outcomes from vaccination and disease.

Model structure

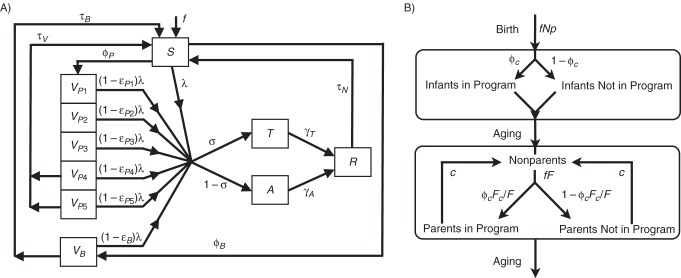

We modeled the epidemiologic states susceptible (S), infected (T, typical infection; A, atypical infection), recovered (R), and vaccinated (VP, primary childhood pertussis vaccination series (diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine); VB, booster Tdap vaccination) (see Figure 1A, Tables 1 and 2, Web Table 1 (available at http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/), Web Appendix 1, and Web Appendix 2), tracking participation of parents and their <6-month-old infants (Figure 1B, Web Appendix 2). To estimate how parental vaccination reduces an infant's risk of pertussis infection, we assumed that an infant's contact time with adults aged 20–40 years in the same household represented contact time with 2 parents or caregivers (19) who could be targeted for parental vaccination, and that the time was split evenly between these two caregivers. Contact time with others was adjusted to maintain the empirically observed mean contact rates (Web Figures 1 and 2, Web Appendix 2).

Figure 1.

A) Schematic of a dynamic model of pertussis transmission showing movement of individuals between epidemiologic states, excluding parental vaccination. Individuals are classified as completely susceptible to pertussis infection (S), vaccinated with 1–5 doses of the primary childhood vaccine series (diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine) (VP1–VP5), vaccinated with the adolescent/adult booster vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) (VB), infected with typical disease (T), infected with atypical disease (A), or temporarily immune to infection (R). Age classes are not shown for clarity. The force of infection, λi = b ΣjCij/Nj(Tj + ρAj), is calculated as a function of the probability of infection per daily infectious contact (b) and the summation of the total number of daily contacts between age classes i and j (Cij) and the fractions of typical (Tj/Nj) and atypical (Aj/Nj) infections in the population. Atypical cases are assumed to be a fraction (ρ) less infectious than typical infections. B) Schematic of a model of parental pertussis vaccination strategies showing the 2 age groups that are partitioned into intervention-related strata. Infants are born at rate f and move out of the intervention after 6 months. Persons aged 20–40 years become parents of newborns at rate f × F, and a fraction (φC) of those parents participate in the intervention. As we evaluate the intervention during the first 6 months of an infant's life, adults retain their classification as parents for only 6 months before moving back into the nonparent class.

Table 1.

Posterior Distributions of Model Parameters for a Dynamic Epidemiologic Model of Pertussis

| Parametera | Base Case | 95% CrIb | Symbol | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of infection given exposure, per minute | 0.0031 | 0.0024, 0.0041 | b | Fitc |

| Efficacy of maternally acquired antibodies | 0.89 | 0.77, 0.93 | m | Fitc |

| Birth rated | 0.05 | f | ||

| Duration of infectiousness, days | ||||

| Typical infection | 25 | 21, 28 | 1/ϒT | 7, 45 |

| Atypical infection | 8 | 4, 10 | 1/ϒA | 7, 45 |

| Effectiveness of DTaP | ||||

| First dose | 0.55 | 0.45, 0.62 | εP1 | 46 |

| Second dose | 0.75 | 0.66, 0.82 | εP2 | 46 |

| Third dose | 0.84 | 0.79, 0.87 | εP3 | 46 |

| Efficacy of DTaP, fourth/fifth dose | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.00 | εP4, εP5 | 47 |

| Duration of DTaP protection, yearse | 23.5 | 17.2, 35.7 | 1/τV | 47 |

| Efficacy of Tdap | 1.00 | 0.86, 1.00 | εB | 48 |

| Duration of Tdap protection, yearse | 2.7 | 2.1, 3.8 | 1/τB | 48 |

| Vaccine coverage | ||||

| First–third doses | φP1-3 | 49 | ||

| 1900–1945 | 0 | |||

| 1946–1994 | 0.7 | 69, 71 | ||

| 1995–2014 | 0.95 | 94, 96 | ||

| Fourth dose | φP4 | 49 | ||

| 1900–1969 | 0 | |||

| 1970–1994 | 0.7 | 69, 71 | ||

| 1995–2014 | 0.85 | 84, 85 | ||

| Fifth dose | φP5 | 49 | ||

| 1900–1969 | 0 | |||

| 1970–1994 | 0.7 | 69, 71 | ||

| 1995–2014 | 0.95 | 94, 96 | ||

| Tdap adolescent dose | φB | 50 | ||

| 2006 | 0.52 | |||

| 2007 | 0.65 | |||

| 2008 | 0.74 | |||

| 2009 | 0.81 | |||

| 2010–2014 | 0.85 |

Abbreviations: CrI, credible interval; DTaP, primary childhood diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis vaccine; Tdap, adolescent/adult tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis booster vaccine.

a All parameters are dimensionless unless otherwise stated.

b 95% credible interval of the posterior distribution.

c Parameter was fitted through a Markov chain Monte Carlo process.

d Annual number of births per adult of childbearing age. The birth rate was set to maintain a stable age distribution in a population with a life expectancy of 80 years and a childbearing period defined as ages 20–40 years.

e Value is the mean of an exponential distribution.

Table 2.

Parameter Values Used in Scenario Analyses for a Dynamic Epidemiologic Model of Pertussis

| Parameter | Base Case | Scenario Analysis |

Symbol | Reference(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | ii | iii | ||||

| Probability of typical infection | ||||||

| <1 year, susceptible | 0.195 | 0.333 | 0.195 | 0.333 | σS1 | 51 |

| <1 year, vaccinated | 0.195 | 0.195 | 0.100 | 0.100 | σV1 | 51 |

| >1 year, susceptible | 0.195 | 0.195 | 0.195 | 0.195 | σS2 | 52, 53 |

| >1 year, vaccinated | 0.195 | 0.195 | 0.100 | 0.100 | σV2 | 52, 53 |

| Relative transmissibility of infectiona | ||||||

| Typical infection | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Atypical infection | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | ρ | ||

| Duration of natural immunity, years | 30 | 20 | 60 | 1/τN | ||

| Reporting rate for typical cases, % | ||||||

| Age <1 year | 1.38 | 0.46 | 1.88 | r1 | 20, 53 | |

| Ages 1–6 years | 0.93 | 0.38 | 1.26 | r2 | ||

| Ages 7–10 years | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.61 | r3 | ||

| Ages ≥11 years | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.41 | r4 | ||

a Dimensionless parameter.

Epidemiologic parameters

We extracted prior distributions for most parameters from clinical and epidemiologic literature (Web Table 1, Web Appendix 2). Given the empirical uncertainty in the probability of infection following exposure, b, and in maternal antibody protection, m, we used uniform priors in estimating these 2 parameters.

Although pertussis is a notifiable disease in the United States, pertussis cases are greatly underreported (20–23). To fully account for pertussis cases, we combined data on reported case counts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (24), hospitalization rates (25), reporting rates for hospitalized cases (20), and active surveillance of nonhospitalized cases (26) (Web Figure 3, Web Appendix 2), which yielded base-case reporting rates of 1.38% (age <1 year), 0.93% (ages 1–6 years), 0.45% (ages 7–10 years), and 0.30% (ages ≥11 years; Web Table 2). We assumed that atypical cases, defined as infections with a cough lasting 5 or fewer days (26), are not severe enough to result in hospitalization or to be reported.

Economic and health outcomes

As with the epidemiologic parameters, we identified distributions for many economic and health outcome parameters from the literature and publicly available data (Tables 3 and 4, Web Appendix 2). We calculated monetary costs in 2013 US dollars, and we estimated health impact in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which take into account both morbidity and mortality (27). Costs were updated to 2013 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Medical Costs (28). We included only direct medical costs and health outcomes applicable to infants who were under 1 year of age and adults who were in the targeted age class of 20–40 years. Indirect costs and productivity losses were not incorporated into the base-case analysis but were included as part of a sensitivity analysis. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated using an annual discount rate of 3% over a 20-year time horizon.

Table 3.

Sampling Distributions for the Health and Economic Outcome Parameters in a Dynamic Epidemiologic Model of Pertussis

| Parameter | Base Casea | Distributionb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of reported outcomes | |||

| Infants under 1 year of age | |||

| Unknown, unreported | 0 | ||

| Outpatientc | 0.793 | ||

| Hospitalization | 0.190 | β (93, 407) | 25 |

| Neurological disease | 0.012 | β (79, 6,529) | 54 |

| Death | 0.005 | β (212, 42,923) | 54 |

| Adults | |||

| Unknown, unreported | 0 | ||

| Moderated | 0.31 | ||

| Severe | 0.66 | β (627, 309) | 29 |

| Hospitalization | 0.03 | β (199, 6,801) | 25 |

| Probability that reported death was in an infant <2 months old | 0.83 | β (53, 10) | 54 |

| Duration of clinical progression, days | |||

| Infants | |||

| Time to improvement | 35 | ln Ν (3.56, 0.112) | 55 |

| Time to recovery | 75 | ln Ν (4.32, 0.112) | 55 |

| Time in hospital | 4 | ln Ν (1.39, 0.072) | 25 |

| Adults | |||

| Time to improvement | 21 | ln Ν (3.04, 0.152) | 55 |

| Time to recovery | 66 | ln Ν (4.19, 0.092) | 55 |

| Time in hospital | 4.6 | ln Ν (1.53, 0.022) | 25 |

| Costs of Tdap vaccination per dose, $US 2013 | |||

| Vaccinee | 21.32 | 56 | |

| Administration | 22.27 | 30 | |

| Adverse effects | 0.93 | 15 | |

| Cost-effectiveness threshold,f $US per QALY | 159,429 | 31 |

Abbreviation: QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; Tdap, adolescent/adult tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis booster vaccine.

a Modal value of the distribution, when distribution is given.

b Distributions are provided with their respective standardized parameter values (a, b for β distributions and µ, σ2 for lognormal distributions).

c Calculated as 1 minus the sum of other infant outcome probabilities.

d Calculated as 1 minus the sum of other adult outcome probabilities.

e Price negotiated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and publicly listed by the Vaccines for Children Program (56).

Table 4.

Health and Economic Outcome Parameters Used in Scenario Analyses for a Dynamic Epidemiologic Model of Pertussis

| Parameter | Base Case | Distributiona | Scenario Analysis |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ib | iic | ||||

| Direct costs of outcomes ($US 2013) | |||||

| Infants | |||||

| Unknown, unreported | 0 | 129 | 0 | ||

| Outpatient | 129 | Γ (1, 129) | 129 | 129 | 29 |

| Hospitalization | 8,553 | Γ (1, 8,553) | 8,553 | 8,553 | 29 |

| Neurological disease | 8,213 | Γ (1, 8,213) | 8,213 | 8,213 | 29 |

| Death | 18,463 | Γ (1, 18,463) | 18,463 | 18,463 | 29 |

| Adults | |||||

| Unknown, unreported | 0 | 65 | 0 | ||

| Moderate | 320 | Γ (1, 320) | 320 | 320 | 57 |

| Severe | 445 | Γ (1, 445) | 445 | 445 | 57 |

| Hospitalization | 3,435 | Γ (1, 3,435) | 3,435 | 3,435 | 57 |

| Quality-of-life weighting | |||||

| Infants, until improvement | |||||

| Unknown, unreportedd | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 29 | |

| Outpatiente | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 29 | |

| Hospitalization | 0.58 | β (171, 124) | 0.58 | 0.58 | 58 |

| Neurological disease | 0.51 | β (146, 140) | 0.51 | 0.51 | 58 |

| Death | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Infants, until recovery | |||||

| Unknown, unreported | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 29 | |

| Outpatient | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 29 | |

| Hospitalization | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 29 | |

| Neurological disease | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 29 | |

| Adults, until improvement | |||||

| Unknown, unreported | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 29 | |

| Moderate | 0.85 | β (115, 20) | 0.85 | 0.85 | 58 |

| Severe | 0.81 | β (99, 23) | 0.81 | 0.81 | 58 |

| Hospitalization | 0.82 | β (96, 21) | 0.82 | 0.82 | 58 |

| Adults, until recovery | |||||

| Unknown, unreported | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 29 | |

| Moderate | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 29 | |

| Severe | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 58 | |

| Hospitalization | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 58 | |

Abbreviation: QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

a Distributions are provided with their respective standardized parameter values (k, θ for Γ distributions and a, b for β distributions).

b Scenario: unreported cases incur both medical costs and QALYs.

c Scenario: unreported cases incur neither costs nor QALYs.

d Set to match adult unknown, unreported cases.

e Set to match adult moderate cases.

We accounted for higher economic costs and greater QALY losses incurred by more severe cases (Web Appendix 2). Consistent with previous work (29), our base case assumed that undiagnosed cases incur the QALY loss of a mild case but no economic costs. We also compared this base case with 2 alternative assumptions: 1) that undiagnosed cases incur the medical costs associated with mild cases or 2) that undiagnosed cases incur neither health costs nor economic costs.

Model-fitting

We used a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach to integrate outcomes over the empirical uncertainty in our epidemiologically relevant parameters (Web Table 1, Web Appendix 2). Posterior distributions were estimated using a likelihood function based on 1) the age-specific incidence of pertussis for 2003–2012 before national ante- or postpartum immunization was introduced (24) and 2) the direct effectiveness of maternally administered pertussis vaccine in newborns (infants less than 2 months old) observed in a case-coverage study following the implementation of antepartum immunization (8).

Cost-effectiveness

We evaluated parental vaccination strategies assuming 75% family participation, a level previously achieved in a pilot study (30). To equivalently compare untargeted adult vaccination, we allocated the same number of vaccine doses for adult vaccination as were used to achieve 75% participation in the maternal vaccination strategy. A strategy was considered “strongly dominated” when it provided less health benefit for greater cost than another strategy and “weakly dominated” when it provided these benefits at a higher incremental cost. For each nondominated strategy, we found the ICER, which measures the cost per QALY of moving to a more expensive strategy that also provides greater benefit. An intervention was deemed cost-effective in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (31) when its ICER was below the willingness-to-pay threshold of $159,429, which is 3 times the per-capita gross domestic product of the United States (32).

Our base-case prediction used the mode of each epidemiologic and economic posterior parameter distribution. For our probabilistic predictions, we sampled from the posterior distributions of all epidemiologic and economic parameters 1,000 times. For each sample, we calculated the incidence of pertussis from 2015 to 2034 under each of our 5 strategies and found the ICER for each strategy.

To compare the cost-effectiveness results from our entire set of predictions, we used a net benefits framework (Web Appendix 2) (33, 34). This framework provides a single outcome measure with which to identify the program that provides the largest health benefit for a given cost-effectiveness threshold. We applied this framework across cost-effectiveness thresholds between $1 per QALY and $1,000,000 per QALY.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed 1-way scenario analyses to examine the sensitivity of our conclusions to the potential variability of parameters whose distributions could not be informed by the literature. For each of these parameters, we first set its value to one of its scenario values (Table 2, Web Appendix 2) and refitted the model as described above to determine posterior distributions for all other parameters not varied in the sensitivity analysis. We then used these new joint posterior distributions to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antepartum maternal vaccination at 75% coverage, relative to no parental vaccination.

For those health and economic outcomes for which we had empirically defined distributions, we performed 1-way sensitivity analyses to identify which parameters contributed most to variability in our probabilistic predictions. Specifically, we set each parameter to the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of its distribution (Tables 3 and 4) and all others to their base-case value. We then again evaluated the cost-effectiveness of antepartum maternal vaccination at 75% coverage, relative to no parental vaccination.

To assess the sensitivity of our results to the social contact structure of the population, we compared our base-case contact matrix based on time-use data from the United States (19) with daily contact counts collected for 8 European countries (18) and refitted our model as described above to the data from each country (Web Appendix 2).

RESULTS

Epidemiologic model-fitting

By fitting the parameter m within our dynamic model both to observational studies of antepartum vaccination effectiveness and to age-stratified social contact data, we estimated that the protection directly conferred upon an infant following antepartum immunization is 89% (95% prediction interval (PI): 77, 93) during the first 2 months of life. The overall antepartum immunization protection for an infant is 91% (8), indicating that the preponderance of protection is derived from maternal antibody transfer rather than reduced transmission from mother to infant.

The probability of infection per minute of contact with an infectious person, b, was estimated to be 0.0031 (95% PI: 0.0024, 0.0041; Web Figures 4 and 5).

Effectiveness predictions

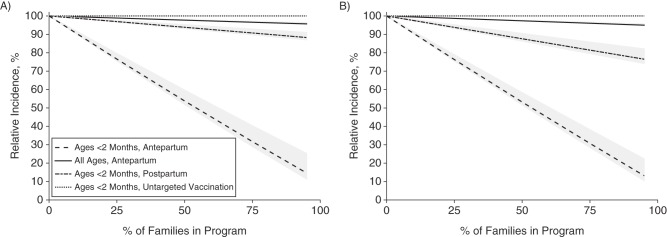

We found that parental vaccination would be substantially more effective than vaccinating the same number of 20- to 40-year-olds using an untargeted strategy (Figure 2). At 75% participation, an antepartum vaccination strategy would reduce pertussis incidence for newborns by 68% (PI: 60, 71) if only mothers were vaccinated (Figure 2A) or by 69% (95% PI: 62, 71) if 2 caregivers were vaccinated (Figure 2B, Web Figure 6, Web Appendix 2). In contrast, a postpartum vaccination strategy with a delay to protection of 7 days would reduce pertussis incidence for newborns by 9% (PI: 7, 10) if only mothers were vaccinated (Figure 2A) or by 19% (PI: 14, 20) if 2 caregivers were vaccinated (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effectiveness of the parental pertussis vaccination strategy at increasing coverage levels when only mothers receive the vaccine (A) and when both parents receive the vaccine (B). The relative incidence of pertussis is calculated over a period of 20 years after program initiation in 2015. Dashed lines indicate the predicted relative incidence in infants aged <2 months for antepartum vaccination, postpartum vaccination, or untargeted vaccination of 20- to 40-year-old adults using the same number of doses as the parental vaccination strategies. The solid line indicates the predicted relative incidence for the entire population. The gray shading shows the 95% prediction interval for each result.

Economic analysis

Evaluation of our model revealed that without parental vaccination, there would be 15.5 (95% PI: 12.0, 20.0) infant deaths from pertussis in the United States annually (Table 5), consistent with an average of 16 (range, 7–31) annual deaths from pertussis reported for 2004–2013 (35). Maternal antepartum vaccination at a participation rate of 75% would avert 9 of these deaths each year. On average, 1 further death would be averted every 3 years by additionally vaccinating the other parent. Approximately, 1,000 QALYs would be gained annually by vaccinating 75% of mothers during pregnancy, while 300 QALYs would be gained from postpartum vaccination.

Table 5.

Cost-Effectiveness Results From a Dynamic Epidemiologic Model of Pertussis

| Vaccination Strategya | Cost ($US Million)b |

No. of QALYs Gainedb |

No. of Deathsb,c |

ICER ($US/QALY)d |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Case | 95% PI | Base Case | 95% PI | Base Case | 95% PI | Base Case | 95% PI | |

| No intervention (strategy 1) | 32 | 4, 88 | 15.5 | 12.0, 20.0 | ||||

| Untargeted (strategy 2) | 60 | 32, 116 | 4 | 1, 4 | 15.5 | 12.0, 20.0 | Weakly dominatede by strategies 1 and 3 | |

| Mother only | ||||||||

| Antepartum, 75% (strategy 3) | 161 | 139, 200 | 1,114 | 709, 1,538 | 6.6 | 4.9, 9.3 | 114,390 | 81,620, 182,530 |

| Postpartum, 75% (strategy 4) | 166 | 140, 219 | 285 | 162, 344 | 14.2 | 10.8, 18.6 | Strongly dominatedf by strategy 3 | |

| Both parents | ||||||||

| Antepartum, 75% (strategy 5) | 296 | 275, 334 | 1,275 | 798, 1,703 | 6.3 | 4.8, 8.8 | 814,320 | 677,980, 1,625,210 |

| Postpartum, 75% (strategy 6) | 301 | 275, 350 | 550 | 314, 667 | 12.9 | 9.7, 17.2 | Strongly dominatedf by strategy 5 | |

Abbreviations: ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; PI, prediction interval; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

a In all strategies, the number of vaccine doses administered is sufficient to cover the parents of 75% of newborns in the population (1 dose per newborn for “mother only” and “untargeted” and 2 doses per newborn for “both parents”).

b Average annual undiscounted data.

c Infants under 1 year of age for whom pertussis is the stated cause of death.

d ICER was discounted at 3% over 20 years. ICER values for “mother only” are relative to the “no intervention” scenario, and ICER values for “both parents” are relative to the “mother only” scenario.

e Confers benefits at a lower cost than the next more expensive strategy but at a higher ICER.

f Confers fewer benefits at a higher cost than an alternative strategy.

The annual undiscounted cost of a program designed to vaccinate 75% of mothers would be $136 million (Table 5). Without parental vaccination, the annual undiscounted medical cost of pertussis in infants and adults would be $32 million. Antepartum maternal vaccination would recoup $8 million of these medical costs annually, compared with no parental vaccination.

Our base-case analysis suggested that at the WHO-recommended threshold for cost-effectiveness, antepartum maternal vaccination would be cost-effective, with an ICER of $114,000 (95% PI: 82,000, 183,000) per QALY gained (Table 5), relative to no parental vaccination. When mothers were vaccinated, however, the vaccination of a second parent would not be cost-effective. Postpartum parental vaccination and untargeted vaccination were dominated by antepartum vaccination (Table 5, Web Figure 7).

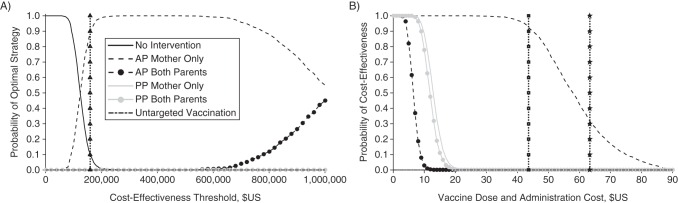

Sensitivity analysis

Incorporating parameter uncertainty, antepartum maternal vaccination is the strategy that is most likely to provide the greatest health benefits at the WHO-recommended threshold for cost-effectiveness, with over 90% certainty (Figure 3A). This conclusion is sensitive to the choice of cost-effectiveness threshold. At cost-effectiveness thresholds below $124,000 per QALY gained, no strategy of parental vaccination would be cost-effective. Between cost-effectiveness thresholds of $124,000 and $1,000,000 per QALY gained, antepartum maternal vaccination is the strategy most likely to be cost-effective. Antepartum vaccination of 2 parents is only optimal when the cost-effectiveness threshold is greater than $1,000,000 per QALY gained. Because antepartum vaccination provides greater health benefits than postpartum or untargeted vaccination, these latter strategies are never cost-effective.

Figure 3.

A) Acceptability curves for parental pertussis vaccination strategies. The curves represent the probability that a strategy will be optimal, such that it results in the largest number of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained across a range of societal willingness-to-pay for QALYs. Curves represent antepartum (AP) vaccination of mothers (short dashes), antepartum vaccination of 2 parents (short dashes with circles), postpartum (PP) vaccination of 1 parent (gray), postpartum vaccination of 2 parents (gray with circles), untargeted vaccination (long dashes), and no intervention (solid black). The participation rate for all parental vaccination strategies was set at 75%, and untargeted vaccination was parameterized to use the same number of doses as maternal vaccination. The threshold for cost-effectiveness recommended by the World Health Organization (vertical dotted line with triangles) is 3 times a country's per-capita gross domestic product ($159,429 for the United States). B) The probability that parental pertussis vaccination at 75% coverage will be cost-effective across a range of vaccination costs. The cost negotiated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (vertical dotted line with squares) and the private cost (vertical dotted line with stars) are both indicated, assuming an administration cost of $22.27 per dose. The threshold for cost-effectiveness was 3 times the US per-capita gross domestic product ($159,429).

The probability that parental vaccination is cost-effective is sensitive to the cost of procuring and administering a dose of the vaccine. At the WHO-recommended threshold for cost-effectiveness and at a total cost of $44 per dose (which includes the CDC-negotiated price of $21 per dose combined with the costs associated with administration), antepartum vaccination of mothers is 92% likely to be cost-effective (Figure 3B). However, at the listed retail price of the vaccine, antepartum maternal vaccination is only 30% likely to be cost-effective. Antepartum vaccination of a second parent and postpartum vaccination of either 1 or 2 parents are all less than 1% likely to be cost-effective at a total cost of $22, which is equal to the estimated cost of administration. Untargeted vaccination is not cost-effective at any price, for even if the vaccine were free, the small cost imposed by side effects would prevent untargeted vaccination from reaching cost-effectiveness.

The cost-effectiveness of maternal antepartum vaccination is also sensitive to the reporting rate. At the lower bound of reporting rates (Table 1), maternal vaccination is predicted to be less effective but to have a lower base-case ICER, with a 69% probability of being cost-effective (Web Figure 8A and 8C). At the higher bound of reporting rates (Table 1), the ICER rises (Web Figure 8A and 8C) and the probability that maternal antepartum vaccination is cost-effective drops to 66%, but the effectiveness of maternal antepartum vaccination remains relatively unchanged. If unreported typical cases incurred no monetary cost or QALY loss, antepartum maternal vaccination would not be cost-effective (Web Figure 8B). Across all reasonable scenarios (Table 1) for ρ, τN, σ, and contact matrix choice, antepartum maternal vaccination remains at least 89% likely to be cost-effective (Web Figure 8C). The effectiveness of postpartum vaccination is sensitive to the choice of contact matrix, but the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antepartum vaccination are not (Web Figures 8 and 9). Much of the variability in the ICER for antepartum vaccination arises from uncertainty surrounding infant health outcomes (Web Figure 10). The inclusion of indirect costs only slightly affects cost-effectiveness (Web Figure 8C). The ICER remains relatively constant as coverage increases (Web Figure 8C), suggesting that herd protection has minimal impact on the effectiveness of these interventions.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis, we reevaluated age-specific reporting rates for pertussis cases and applied recent empirical data on the effectiveness of antepartum maternal vaccination, estimates of Tdap efficacy waning, and social mixing patterns to demonstrate that the currently recommended program of antepartum maternal vaccination is a cost-effective vaccination strategy. Antepartum maternal vaccination offers dramatic direct protection to infants in the first 2 months of life, when they are most vulnerable both to infection and to severe outcomes. We find antepartum vaccination to be the most efficient strategy per Tdap vaccine dose when compared with postpartum vaccination, antepartum vaccination of a second parent, or untargeted vaccination of comparably aged adults. These conclusions are robust to parameter uncertainty. Thus, our results strongly suggest that efficient prevention of pertussis in infants begins before birth.

The WHO suggests that interventions that confer a life-year of health benefits at a cost less than 3 times a country's per-capita gross domestic product be considered “cost-effective” (31). This equates to a cost-effectiveness threshold of $159,429 per QALY for the United States, and we used this as our base-case threshold. In practice, the United States does not have a strictly defined cost-effectiveness threshold. Recent work suggests that thresholds of $100,000 and $200,000 per QALY might also be appropriate (36), while other studies suggest a threshold between $183,000 and $264,000 per QALY (37). To support decision-making across a wide range of cost-effectiveness thresholds, we evaluated the cost-effectiveness of parental vaccination across thresholds between $1 per QALY and $1,000,000 per QALY (Figure 3A).

We used the listed CDC-negotiated price of a dose of Tdap vaccine for our base-case analysis, as studies have demonstrated that the CDC price is a better match for the mean purchase price of adolescent Tdap vaccines than the listed private price (38). We conservatively assumed that the cost of Tdap administration for pregnant women was identical to that for postpartum administration in a hospital setting (30). Administration costs are likely to be lower outside a hospital setting, which would further improve the cost-effectiveness ratio for antepartum vaccination.

Our findings stand in contrast to a static cost-effectiveness evaluation for the United States which found that antepartum maternal vaccination would not be cost-effective (14). Principally, our analysis arrived at a lower ICER than the previous study because of our comprehensive reporting rate calculation based on empirical data (20, 24–26). The calculation takes into account age-specific and severity-specific biases in reporting, and we estimated a lower reporting rate than was used in the previous study. Conversely, previous economic evaluations of postpartum vaccination (15–17, 39) estimated higher effectiveness for postpartum vaccination, even to the point of cost-saving (15), than does our dynamic model. These studies assumed that those infants who were infected via an unvaccinated mother would not be susceptible to infection from any other source, should the mothers be vaccinated and removed as a source of infection. This assumption is likely to result in overestimation of the impact of postpartum maternal vaccination. We also found that the country-specific structure of social interactions and dynamically modeled risk are fundamental to the effectiveness of postpartum vaccination. To our knowledge, our study is the first to have used empirical contact data to evaluate parental vaccination strategies.

We estimated the direct protection conferred upon an infant by maternal vaccination over the first 2 months of life to be 89%. This direct protection is comparable to the efficacy provided to older infants by the full primary vaccination series (40). Because there is only a slight impact from herd protection as coverage increases, we recommend vaccination of as many pregnant women in the United States as possible. Nonetheless, while uptake of the pertussis vaccine by pregnant women in the United States has been high, it has not been universal (41). Perfect antepartum coverage is unlikely to be attained in the United States, given that fewer than half of pregnant women in the United States receive the recommended seasonal influenza vaccine (42) and nearly one-quarter do not receive adequate general antepartum care (43). For those women who are not vaccinated during pregnancy, the ACIP recommends postpartum immunization to reduce the risk of pertussis transmission to the newborn. Our results suggest that this would not meet WHO criteria for cost-effectiveness but would be a more efficient administration of a dose of Tdap than untargeted adult vaccination (the concurrent ACIP recommendation). Compared with the scenario without any adult vaccination, untargeted vaccination has a cost-effectiveness ratio in excess of $6 million per QALY. Consequently, this result underscores the cost-effectiveness of antepartum vaccination relative to the other ACIP recommendations that are actively implemented in the United States to address pertussis.

It is possible that both antepartum protection and postpartum protection extend beyond the time frames we have modeled. We accounted for 2 months of direct maternal antibody protection, consistent with the time frame used for the case coverage analysis from which the maternal protection was parameterized (8) and after which a significant drop in infant antibody concentration occurs (13). We assumed indirect protection to extend to 6 months, after which point the primary vaccination series is complete. In both cases, it is possible that protection extends beyond these time frames, particularly from antibody transfer through breastfeeding (44). Further research regarding the mechanism of infant protection could elucidate additional pathways of protection following postpartum vaccination, thereby increasing its effectiveness. Regardless of mechanism, it is clear that vaccination of mothers during pregnancy is a cost-effective intervention that provides extraordinary protection against pertussis to infants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom (Katherine E. Atkins); Center for Infectious Disease Modeling and Analysis, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (Meagan C. Fitzpatrick, Alison P. Galvani); and Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (Jeffrey P. Townsend).

The first 2 authors contributed equally to the paper.

Funding was received from the Notsew Orm Sands Foundation (Houston, Texas) and Sanofi-Pasteur (Lyon, France). K.E.A. was partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit in Immunisation at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, in partnership with Public Health England. We used the Yale University Biomedical High Performance Computing Center, which is supported by National Institutes of Health grants RR19895 and RR029676-01, for model analysis.

We thank Dr. Jan Medlock for providing contact matrix code, Dr. Nick Carriero for computing support, Drs. A. David Paltiel and Martial Ndeffo-Mbah for discussions regarding cost-effectiveness analysis, and Dr. Forrest Crawford for insights regarding vaccine effectiveness. We thank Drs. Emilio Zagheni and Joël Mossong for providing us with contact data from their respective studies. We also thank the participants in the Modeling of Infectious Disease Agents Study (MIDAS) pertussis workshop (Atlanta, Georgia, April 10, 2014) and the Global Summit Meeting of the Global Pertussis Initiative (Dublin, Ireland, May 10–11, 2014) for informative discussions.

The funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the United Kingdom National Health Service, the United Kingdom National Institute for Health Research, the United Kingdom Department of Health, or Public Health England.

K.E.A., M.C.F., A.P.G., and J.P.T. have consulted for Sanofi-Pasteur and M.C.F., A.P.G., and J.P.T. for Merck & Co., Inc. (Kenilworth, New Jersey) regarding pertussis vaccination.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;3759730:1969–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skoff TH, Cohn AC, Clark TA et al. Early impact of the US Tdap vaccination program on pertussis trends. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;1664:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz JA, Capua T, Bocchini JA Jr. Update on child and adolescent immunizations: selected review of US recommendations and literature. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;243:407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wendelboe AM, Njamkepo E, Bourillon A et al. Transmission of Bordetella pertussis to young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;264:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skoff TH, Kenyon C, Cocoros N et al. Sources of infant pertussis infection in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;1364:635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;627:131–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Rie A, Hethcote HW. Adolescent and adult pertussis vaccination: computer simulations of five new strategies. Vaccine. 2004;22(23-24):3154–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet. 2014;3849953:1521–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dabrera G, Amirthalingam G, Andrews N et al. A case-control study to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in protecting newborn infants in England and Wales, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;603:333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gall SA, Myers J, Pichichero M. Maternal immunization with tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis vaccine: effect on maternal and neonatal serum antibody levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2044:334.e1–334.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halperin BA, Morris A, Mackinnon-Cameron D et al. Kinetics of the antibody response to tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine in women of childbearing age and postpartum women. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;539:885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leuridan E, Hens N, Peeters N et al. Effect of a prepregnancy pertussis booster dose on maternal antibody titers in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;307:608–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munoz FM, Bond NH, Maccato M et al. Safety and immunogenicity of tetanus diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy in mothers and infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;31117:1760–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terranella A, Asay GRB, Messonnier ML et al. Pregnancy dose Tdap and postpartum cocooning to prevent infant pertussis: a decision analysis. Pediatrics. 2013;1316:e1748–e1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coudeville L, Van Rie A, Getsios D et al. Adult vaccination strategies for the control of pertussis in the United States: an economic evaluation including the dynamic population effects. PLoS One. 2009;47:e6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Greeff SC, Lugnér AK, van den Heuvel DM et al. Economic analysis of pertussis illness in the Dutch population: implications for current and future vaccination strategies. Vaccine. 2009;2713:1932–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westra TA, de Vries R, Tamminga JJ et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of various pertussis vaccination strategies primarily aimed at protecting infants in the Netherlands. Clin Ther. 2010;328:1479–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mossong J, Hens N, Jit M et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 2008;53:e74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zagheni E, Billari FC, Manfredi P et al. Using time-use data to parameterize models for the spread of close-contact infectious diseases. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;1689:1082–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutter RW, Cochi SL. Pertussis hospitalizations and mortality in the United States, 1985–1988. Evaluation of the completeness of national reporting. JAMA. 1992;2673:386–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka M, Vitek CR, Pascual FB et al. Trends in pertussis among infants in the United States, 1980–1999. JAMA. 2003;29022:2968–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortese MM, Baughman AL, Zhang R et al. Pertussis hospitalizations among infants in the United States, 1993 to 2004. Pediatrics. 2008;1213:484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldwyn EE, Rohani P. Bias in pertussis incidence data and its implications for public health epidemiology. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;194:379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough). Surveillance and reporting. http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html Published August 31, 2015. Accessed November 19, 2015.

- 25.Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Pertussis—whooping cough. http://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/immunization/pertussis.htm Published September 17, 2015. Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 26.Ward JI, Cherry JD, Chang S-J et al. Efficacy of an acellular pertussis vaccine among adolescents and adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;35315:1555–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein MC, Stason WB. Foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. N Engl J Med. 1977;29613:716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index. Measuring price change for medical care in the CPI. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpifact4.htm Published April 12, 2010. Accessed November 19, 2015.

- 29.Lee GM, Murphy TV, Lett S et al. Cost effectiveness of pertussis vaccination in adults. Am J Prev Med. 2007;323:186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Healy CM, Rench MA, Baker CJ. Implementation of cocooning against pertussis in a high-risk population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;522:157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Choosing Interventions That Are Cost Effective (WHO-CHOICE). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The World Bank. Data. GDP per capita (current US$). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD/countries Accessed November 19, 2015.

- 33.Stinnett AA, Mullahy J. Net health benefits: a new framework for the analysis of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Making. 1998;18(2 suppl):S68–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Briggs AH, Goeree R, Blackhouse G et al. Probabilistic analysis of cost-effectiveness models: choosing between treatment strategies for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Med Decis Making. 2002;224:290–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER [database]. About Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2013. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html Accessed March 9, 2015.

- 36.Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness—the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;3719:796–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braithwaite RS, Meltzer DO, King JT Jr et al. What does the value of modern medicine say about the $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year decision rule? Med Care. 2008;464:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freed GL, Cowan AE, Gregory S et al. Variation in provider vaccine purchase prices and payer reimbursement. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 5):S459–S465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lugnér AK, van der Maas N, van Boven M et al. Cost-effectiveness of targeted vaccination to protect new-borns against pertussis: comparing neonatal, maternal, and cocooning vaccination strategies. Vaccine. 2013;3146:5392–5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quinn HE, Snelling TL, Habig A et al. Parental Tdap boosters and infant pertussis: a case-control study. Pediatrics. 2014;1344:713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldfarb IT, Little S, Brown J et al. Use of the combined tetanus-diphtheria and pertussis vaccine during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2113:299.e1–299.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—29 states and New York City, 2009–10 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;617:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. Prenatal services. http://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/womeninfants/prenatal.html Accessed November 20, 2015.

- 44.Abu Raya B, Srugo I, Kessel A et al. The induction of breast milk pertussis specific antibodies following gestational tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccination. Vaccine. 2014;3243:5632–5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coudeville L, van Rie A, Andre P. Adult pertussis vaccination strategies and their impact on pertussis in the United States: evaluation of routine and targeted (cocoon) strategies. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;1365:604–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn HE, Snelling TL, Macartney KK et al. Duration of protection after first dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in infants. Pediatrics. 2014;1333:e513–e519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Misegades LK, Winter K, Harriman K et al. Association of childhood pertussis with receipt of 5 doses of pertussis vaccine by time since last vaccine dose, California, 2010. JAMA. 2012;30820:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koepke R, Eickhoff JC, Ayele RA et al. Estimating the effectiveness of tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) for preventing pertussis: evidence of rapidly waning immunity and difference in effectiveness by Tdap brand. J Infect Dis. 2014;2106:942–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Immunization Survey (NIS)—children (19–35 months). U.S. vaccination coverage reported via NIS. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/nis/child/index.html Published 2013. Updated January 29, 2016. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;6234:685–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heininger U, Kleemann WJ, Cherry JD et al. A controlled study of the relationship between Bordetella pertussis infections and sudden unexpected deaths among German infants. Pediatrics. 2004;1141:e9–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cherry JD. The epidemiology of pertussis: a comparison of the epidemiology of the disease pertussis with the epidemiology of Bordetella pertussis infection. Pediatrics. 2005;1155:1422–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ward JI, Cherry JD, Chang S-J et al. Bordetella pertussis infections in vaccinated and unvaccinated adolescents and adults, as assessed in a national prospective randomized Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Trial (APERT). Clin Infect Dis. 2006;432:151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis—United States, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;5450:1283–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee LH, Pichichero ME. Costs of illness due to Bordetella pertussis in families. Arch Fam Med. 2000;910:989–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for Children Program (VFC). CDC vaccine price list. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/awardees/vaccine-management/price-list/ Published August 1, 2014. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- 57.Lee GM, Lett S, Schauer S et al. Societal costs and morbidity of pertussis in adolescents and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;3911:1572–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee GM, Salomon JA, LeBaron CW et al. Health-state valuations for pertussis: methods for valuing short-term health states. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.