Abstract

Motivation: Convolutional neural networks (CNN) have outperformed conventional methods in modeling the sequence specificity of DNA–protein binding. Yet inappropriate CNN architectures can yield poorer performance than simpler models. Thus an in-depth understanding of how to match CNN architecture to a given task is needed to fully harness the power of CNNs for computational biology applications.

Results: We present a systematic exploration of CNN architectures for predicting DNA sequence binding using a large compendium of transcription factor datasets. We identify the best-performing architectures by varying CNN width, depth and pooling designs. We find that adding convolutional kernels to a network is important for motif-based tasks. We show the benefits of CNNs in learning rich higher-order sequence features, such as secondary motifs and local sequence context, by comparing network performance on multiple modeling tasks ranging in difficulty. We also demonstrate how careful construction of sequence benchmark datasets, using approaches that control potentially confounding effects like positional or motif strength bias, is critical in making fair comparisons between competing methods. We explore how to establish the sufficiency of training data for these learning tasks, and we have created a flexible cloud-based framework that permits the rapid exploration of alternative neural network architectures for problems in computational biology.

Availability and Implementation: All the models analyzed are available at http://cnn.csail.mit.edu.

Contact: gifford@mit.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

The recent application of convolutional neural networks (LeCun et al., 2015; Salakhutdinov, 2015) to sequence-based problems in genomics signals the advent of the deep learning era in computational biology. Two recent methods, DeepBind (Alipanahi et al., 2015) and DeepSEA (Zhou and Troyanskaya, 2015), successfully applied deep learning to modeling the sequence specificity of protein binding with a performance superior to the best existing conventional learning methods. Learning tasks in genomics often have tens of thousands or more training examples, which makes them well adapted to training convolutional neural networks without overfitting. Such training examples are typically drawn from high-throughput data, such as those produced by the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project (Bernstein et al., 2012).

The convolutional neural networks used by DeepBind and DeepSEA are essential building blocks in deep learning approaches in computer vision (Krizhevsky et al., 2012; Le, 2013; LeCun et al., 2015; Sainath et al., 2013; Tompson et al., 2014a, b). The adaptation of convolutional neural networks from computer vision to genomics can be accomplished by considering a window of genome sequence as an image. Instead of processing 2-D images with three color channels (R,G,B), we consider a genome sequence as a fixed length 1-D sequence window with four channels (A,C,G,T). Therefore the genomic task of modeling DNA sequence protein-binding specificity is analogous to the computer vision task of two-class image classification. One of the biggest advantages of a convolutional neural network for genomics is its ability to detect a motif wherever it is in the sequence window, which perfectly suits the task of motif identification and hence binding classification.

We have conducted a systematic exploration of the performance of convolutional network architectures for the fundamental genomic task of characterizing the binding affinity of transcription factors to DNA sequence in 690 different ChIP-seq experiments. We designed a pool of nine architecture variants by changing network width, depth and pooling designs. We varied each of these dimensions while observing classification performance on each transcription factor independently.

The two tasks we chose to explore are motif discovery and motif occupancy. The motif discovery task classifies sequences that are bound by a transcription factor from negative sequences that are dinucleotide shuffles of the positively bound sequences. The motif occupancy task discriminates genomic motif instances that are bound by a transcription factor (positive set) from motif instances that are not bound by the same transcription factor (negative set) in the same cell type, where GC-content and motif strength are matched between the positive and negative set.

We found for both tasks, classification performance increases with the number of convolution kernels, and the use of local pooling or more convolutional layers has little, if not negative, effect on the performance. Convolutional neural network architectures that took advantage of these insights exceeded the classification performance of DeepBind, which represents one particular point in the parameter space that we tested.

2 Background

2.1 A parameterized convolutional neural network architecture

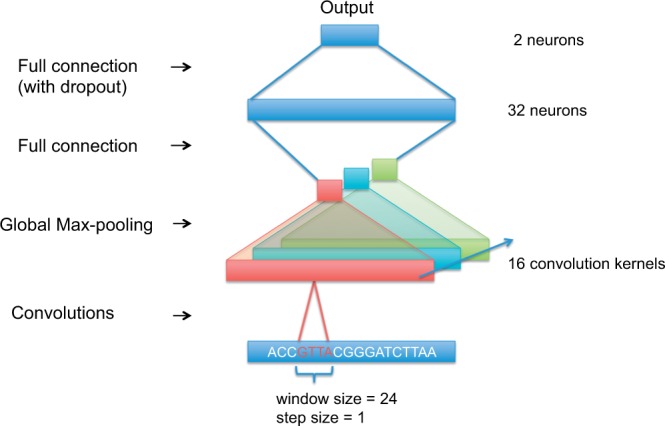

The convolutional neural network architectures we evaluated are all variations of Figure 1. The input is a matrix where L is the length of the sequence (101 bp in our tests). Each base pair in the sequence is denoted as one of the four one-hot vectors and .

Fig. 1.

The basic architectural structure of the tested convolutional neural networks

The first layer of our network is a convolutional layer, which can be thought of as a motif scanner. For example, DeepBind uses 16 convolutional layers, each scanning the input sequence with step size 1 and window size of 24. The output of each neuron on a convolutional layer is the convolution of the kernel matrix and the part of the input within the neuron’s window size.

The second layer is a global max-pooling layer, one for each convolutional layer. Each of these max-pooling layers only outputs the maximum value of all of its respective convolutional layer outputs. The function of this global max-pooling process can be thought of as calling whether the motif modeled by the respective convolutional layer exists in the input sequence or not.

The third layer is a fully connected layer of size 32. Because it is fully connected, each of its 32 neurons is connected to all of the neurons in the max-pooling layer. A dropout layer (Srivastava et al., 2014) is used on the third layer output to randomly mask portions of its output to avoid overfitting. In the published DeepBind model the inclusion of the third layer may be omitted for a given TF to optimize performance. We always include the third layer followed by a dropout layer.

The final output layer consists of two neurons corresponding to the two classification results. These two neurons are fully connected to the previous layer.

We implemented our generic convolutional neural network using the Caffe (Jia et al., 2014) platform. We used Amazon EC2 GPU-enabled machine instances to train and test our networks efficiently, and we are making our scalable Amazon EC2 implementation available with this paper for others to use and extend (http://cnn.csail.mit.edu).

We constructed a series of architectures by varying one of three parameters: the number of kernels, the number of layers, or the pooling method at the top layer (Table 1). Each of these parameters contributes to network performance in different aspects. Additional convolutional kernels add power in detecting motif variants and co-factor motifs. Additional layers of convolution and max-pooling make the neural network ‘deeper’ and enable the model to extract features such as motif interactions at the price of making the network much harder to train. The use of global max-pooling reduces motif information to present or not-present in the input sequence, while local max-pooling retains the location of the motif.

Table 1.

The code and brief description of the 9 variants of CNN models compared in this work

| Code | Architecture (relative to 1layer structure) |

|---|---|

| 1layer | The basic structure as depicted in Figure 1 |

| 1layer_1motif | Use 1 convolutional kernels |

| 1layer_64motif | Use 64 convolutional kernels |

| 1layer_128motif | Use 128 convolutional kernels |

| 1layer_local_win9 | Use local maxpooling of window size 9 at top |

| 1layer_local_win3 | Use local maxpooling of window size 3 at top |

| 2layer | 2 layers with 16/32 kernels |

| 3layer | 3 layers with 16/32/64 kernels |

| 2layer_local_win3 | 2 layers with 16/32 kernels, use local maxpooling of window size 3 at top |

| 3layer_local_win3 | 3 layers with 16/32/64 kernels, use local maxpooling of window size 3 at top |

More detailed description of the models can be found on our supporting website.

We note that with more than one layer, the pooling at intermediate layers must be local for higher layer of convolution to be meaningful. We explored using both global pooling and local pooling at the top layer in the deep networks we tested to investigate the combinatorial effects of additional layers and the pooling type at the top layer. We use more kernels for deeper convolutional layers to characterize the different combination of lower-level features, an architecture design that has been adopted by many successful convolutional neural network models in computer vision (Krizhevsky et al., 2012) and genomics (Zhou and Troyanskaya, 2015).

3 Results

3.1 Experiment setup

We used 690 transcription factor ChIP-seq experiments from the ENCODE project to benchmark the performance of different models compared in this work.

We constructed separate positive and negative datasets for the motif discovery and motif occupancy tasks. In the motif discovery task, we used the same preprocessing procedure as Alipanahi et al. (2015) and centered our 101 bp positive (bound) sequences on ChIP-seq binding events. The negative set consists of shuffled positive sequences with dinucleotide frequency maintained. In this task, the goal is to discover the motif combination from a similar nucleotide background. In the motif occupancy task, both the positive and negative sets are 101 bp regions centering at a motif instance, with the size, GC-content and motif strength matched. The label of each region is determined by whether it overlaps with any ChIP-seq region. In this task, the model will have to capture a sequence determinant more complicated than motifs. It is important to note that the motif learning task, by construction, discriminates between genomic and non-genomic (artificial) sequences, while the motif occupancy task discriminates between two groups of genomic sequences. In both tasks, we randomly sampled 80% of the data to use as the training set and used the rest as the testing set.

We compare the performance of the convolutional neural network configurations by the median area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) for all 690 experiments. We used two controls on all transcription factor datasets, the original DeepBind implementation and a recent state-of-the-art discriminative sequence-based method, the gapped k-mer support vector machine (gkm-SVM) (Ghandi et al., 2014).

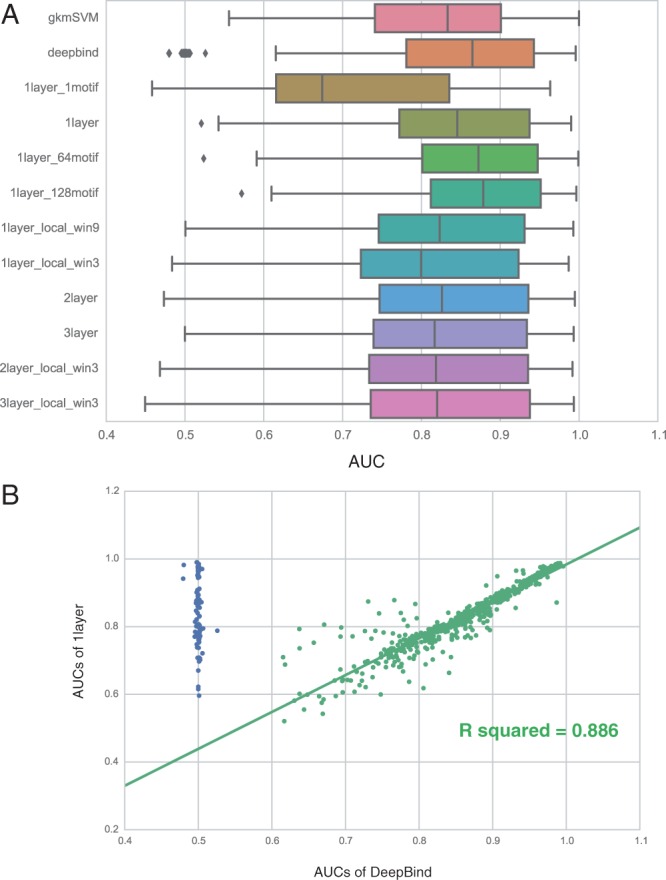

3.2 A simple model outperforms in motif discovery

In the motif discovery task, our basic structure (1layer) with the same configuration as DeepBind achieved nearly identical performance to the original DeepBind implementation. Our basic model achieves slightly lower median AUC but fewer AUCs close to 0.5 (Fig. 2A) than DeepBind. DeepBind instances with AUCs close to random could result from improper weight initialization. With the instances with AUC close to 0.5 for DeepBind excluded, linear regression between the AUCs from the two models yielded a good fit with an R2 of 0.886 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

(A) The distribution of AUCs across 690 experiments in the motif discovery task. (B) The performance of our basic model (1layer) matches DeepBind. Blue points are the transcription factors with AUCs close to 0.5 for DeepBind but not for our basic model

We found that additional convolutional kernels (1layer_64motifs, 1layer_128motifs) increased performance for the motif discovery task (Fig. 2A). As kernels are analogous to motif scanners, this observation emphasizes the need to use sufficient kernels to capture motif variants. We note that the improvement seemed to be almost saturated when more than 128 kernels were deployed for the 690 experiments we tested.

Surprisingly, while local max-pooling is popular in the practice of deep learning in computer vision (Krizhevsky et al., 2012; Le, 2013; LeCun et al., 2015; Sainath et al., 2013; Tompson et al., 2014a, b), we observed that local max-pooling (1layer_local_win3, 1layer_local_win9) achieved a performance inferior to model with a simple global max-pooling strategy. We found the more ‘local’ the max-pooling window, the worse performance we observed. Thus for the motif discovery task, retaining more information than the binary existence of the motif does not help as much as the negative effect from added noise.

For the motif discovery task we found that adding more lower layers (2layer, 3layer) to perform feature transformation reduced performance when compared to our basic structure with a single layer. Using local max-pooling at the top (2layer_local_win3, 3layer_local_win3) did not improve performance for deeper networks when compared to our basic structure. Thus, perhaps surprisingly, we conclude that deep architectures are not necessary for the motif discovery task.

3.3 CNNs excel in capturing higher-order features

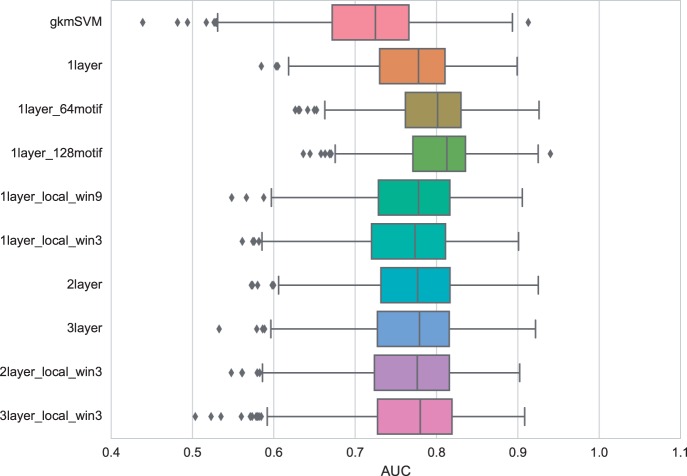

The motif occupancy task is much harder than motif discovery, as we strictly matched the distribution of motif strength in the positive and negative set and therefore eliminate the contribution of motif strength to binding prediction (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, in this task CNNs also achieved good performance with an AUC close to 0.8, outperforming gkmSVM (Fig. 3). Similar to our observations for the motif discovery task, the number of convolutional kernels has the greatest impact on the performance, indicating that the adequate characterization of simple features is still crucial for this task where motif strength has been controlled. This observation reflects the limited power of motifs in characterizing the binding specificity of transcription factors. Unlike in motif discovery, the use of local pooling and adding more layers gave rise to similar, if not better, performance compared to the basic model. This suggests that when motif presence is controlled, capturing other high-level features in the sequence context could compensate for the loss of performance due to model complexity. However, the strength of these high-level features is limited. We excluded DeepBind in the motif occupancy task because DeepBind does not take customized negative samples in training, but instead fixed its negative samples as the shuffled positive sequence with di-nucleotide frequency maintained.

Fig. 3.

The distribution of AUCs across 690 experiments in the motif occupancy task

To further explore how CNNs perform in capturing higher-order features, we generated an additional pair of positive and negative sets which is similar to that of the motif occupancy task but the location of motif in the sample is no longer controlled in the positive sample. In this case, the location of the motif, which is higher-order information, needs to be learned. We found the basic CNN excelled in this task, especially when we used local pooling which enables the network to remember the location of the features (Supplementary Fig. S2).

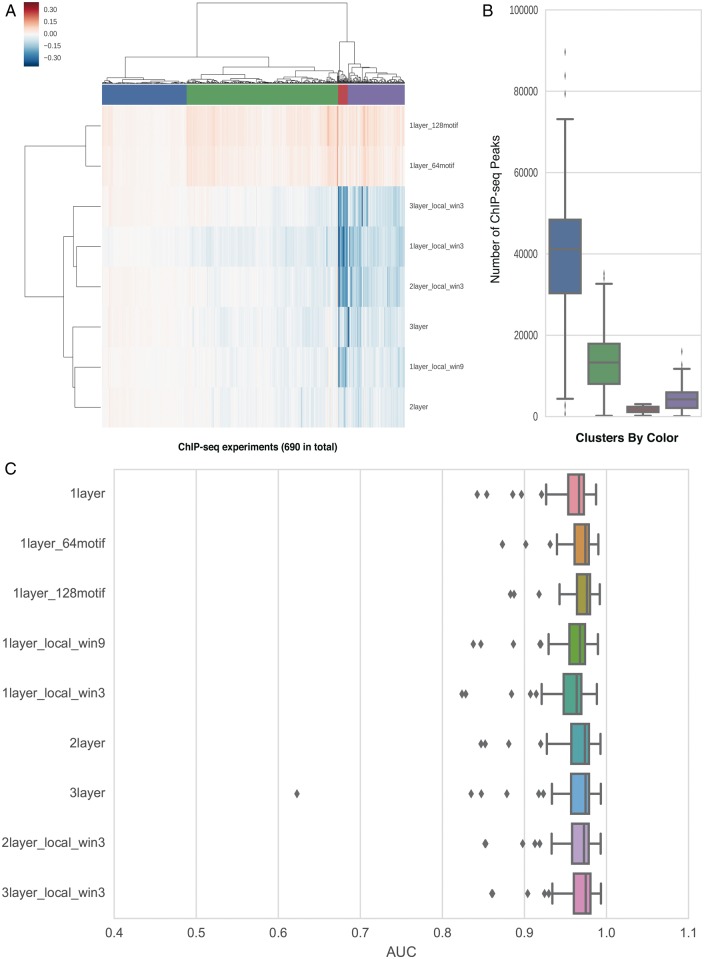

3.4 Complex convolutional neural network models require sufficient training data

We found that convolutional neural network performance decreases with network complexity when there is insufficient training data for a given ChIP-seq experiment. For each experiment, we calculated the change of AUC in motif discovery task from the basic 1layer model to each of the eight model variants in Table 1. When we clustered the change in performance for each experiment using hierarchical clustering with Ward linkage (Fig. 4A), we observed four clusters of performance. Two clusters (Fig. 4A, red and violet) have worse performance when more complex models are used, one cluster (blue) has similar AUCs across models, and a fourth cluster (green) is between these extremes. After comparing the distribution of sample sizes within each cluster, we observed a strong positive correlation between the amount of available training data for an experiment and its performance with complex models, suggesting the need for sufficient training data for complex models (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

(A) The effect of different architectures on AUC is experiment-specific. Each column of the heat map denotes one ChIP-seq experiment. Each row represents one model variant. Each value in the heatmap shows the change of AUC in motif discovery task from the basic model 1layer to a variant model. Four clusters from hierarchical clustering are colored in blue, green, red and violet. (B) The number of called ChIP-seq peaks in each of the fours clusters. The colors of the clusters match those in (A). (C) The distribution of AUCs in the motif discovery task across 112 ChIP-seq experiment with 40000 peaks

We further investigated how sensitive different architectures are to input dataset size. We used 112 ChIP-seq datasets which have more than 40 000 binding events, and constructed three new sets of experiments, each of which has 112 datasets, by down-sampling each original ChIP-seq dataset to have 40 000, 10 000 and 2500 binding events respectively. We trained and evaluated the same set of architectures in the motif discovery task on these three sets of experiments. With 40 000 training samples, all of the models achieved similar performance and the models with more than one layer performed slightly better than the basic structure (Fig. 4C). With smaller sample sizes, the models with more complex architectures showed notably inferior performance and the gap expanded as the sample size further decreased (Supplementary Fig. S3).

We next explored if the family of a transcription factor contributes to the TF’s performance. We mapped the 112 ChIP-seq datasets to 10 TF families using TF family annotations in the JASPAR database. We performed a two-way ANOVA test to disentangle the contributions of TF family, model architecture, and their interaction on the AUC of an experiment. When evaluated on the set of datasets with 40 000, 10 000 and 2500 peaks respectively to control for the sample size, the model architecture is always the only factor causing changes of AUC with statistical significance (). Evaluated by , the effect size of TF family and the interaction term are also always 50 times less than that of the model architecture. Thus the family of TF only contributes marginally to the variance in the AUC.

3.5 Deeper networks are much more time-consuming to train

We further analyzed the time-performance tradeoff for different architectures. For each architecture, the time needed to train on 500 000 samples in the motif discovery task was calculated (Table 2). Adding layers requires the most additional training time.

Table 2.

The training time for different model variants to train on 500 000 samples

| Model | Time for training on 500 000 samples (s) |

|---|---|

| 1layer | 64.34 |

| 1layer_64motif | 79.45 |

| 1layer_128motif | 94.47 |

| 1layer_local_win9 | 68.08 |

| 1layer_local_win3 | 73.12 |

| 2layer | 91.82 |

| 3layer | 124.12 |

| 2layer_local_win3 | 93.34 |

| 3layer_local_win3 | 125.5 |

4 Methods

4.1 ChIP-seq data for benchmark

As was performed in Alipanahi et al. (2015) and Zhou and Troyanskaya (2015), we obtained 690 ChIP-seq experiments from ENCODE (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/encodeDCC/wgEncodeAwgTfbsUniform/)

We constructed separate datasets for motif discovery and motif occupancy. In the task of motif discovery, the positive set consists of the centering 101 bp region of each ChIP-seq peak, and the negative set consists of shuffled positive sequences with matching dinucleotide composition. This is the same negative set used in DeepBind (Alipanahi et al., 2015). The shuffling was performed using the ‘fasta-dinucleotide-shuffle’ package in MEME (Bailey et al., 2009). In the motif occupancy task, we limit it to 422 TF ChIP-seq experiments where the motif is present in the JASPAR database. Then the motif instances were identified from the whole genome using the FIMO package from the MEME suite (Bailey et al., 2009) and labeled by whether the 101bp region centered at the motif overlaps with any ChIP-seq peak. Lastly we matched the size, GC-content and motif strength (using the P-value determined from FIMO) of the positive and negative set in the same way as described in Whitaker et al. (2015)

For each ChIP-seq experiment, performance was measured by randomly shuffling the factor’s positive set, randomly shuffling the factor’s negative set, and using 80% of each set for training and the remaining 20% for testing. For convolutional neural network models we randomly sampled 1/8 of the training set as the validation set, which was used for hyper-parameter search. In all cases, the test set was held out until evaluating the performance of the model.

4.2 Implementation of the parameterized convolutional neural network

We built our parameterized convolutional neural network using Caffe (Jia et al., 2014). We performed hyper-parameter search using Mri (https://github.com/Mri-monitoring/Mri-docs/blob/master/mriapp.rst). For each ChIP-seq experiment, 30 hyper-parameter settings were randomly sampled from all possible combinations, which is the same as the number used by DeepBind. Details of the hyper-parameter space are summarized in Table 3. Note that although the structure of DeepBind was replicated in our basic model, we selected different methods for weight initialization and optimization because of the differences between DeepBind’s codebase and our Caffe-based platform. Additionally, in DeepBind, the use of a fully connected layer of 32 neurons and a dropout layer before the output layer is a binary hyper-parameter, while in our Caffe-based implementation this was not easily feasible. Thus we always include these two layers in all of our model variants.

Table 3.

Hyper-parameter sets tested

| Hyper-parameter | Choices |

|---|---|

| Dropout ratio | 0.75, 0.5, 0.1 |

| Momentum in AdaDelta optimizer | 0.9, 0.99, 0.999 |

| Delta in AdaDelta optimizer | 1e-4, 1e-6, 1e-8 |

There are three phases in training and evaluating a model. In the hyper-parameter search phase we used 30 candidate hyper-parameter settings. For each potential hyper-parameter setting we trained a model on the training set and tested it on the validation set every 100 mini-batches of training. In the training phase, the hyper-parameter set with the best validation accuracy in the last phase was used to train the model on the training set and test on the validation set every 500 mini-batches of training. The iteration with the best validation accuracy was picked as the final model. In the testing phase, we tested the model on the test set, which was held out completely in the first two phases.

Our implementation has been packaged using Docker to make it runnable on any Unix-based system. All of the experiments were performed on Amazon Elastic Cloud (EC2). Detailed instruction of how to run the model on Amazon EC2 can be found on our paper’s supporting website (http://cnn.csail.mit.edu).

4.3 Comparison with gkm-SVM and DeepBind

We used the default training parameters for the gkm-SVM R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gkmSVM) for all of our experiments. As was described in Zhou and Troyanskaya (2015), the gkm-SVM software does not scale to using all binding sites because of its requirement to compute a full kernel matrix. Therefore we randomly sampled 5000 positive sequences if the number of total positives exceeds 5000, as was adopted in Zhou and Troyanskaya (2015).

We obtained the source code of DeepBind from http://tools.genes.toronto.edu/deepbind/nbtcode/ and packaged it with Docker so it can be run on different systems without dependency problems. Our adapted version can be found on our website. All of the DeepBind experiments were run on Amazon EC2 using g2.2xlarge instances.

4.4 Runtime evaluation

We used the time recorded in the training log of Caffe. We took the time difference of the iteration 0 and iteration 5000 where in each iteration a mini-batch of 100 samples were fed into the model. Thus we evaluated the time each model needed for training on half a million samples.

5 Discussion

Convolutional neural networks are capable of learning sophisticated features, however their performance does not increase monotonically with their complexity. Thus the design of a convolutional neural network needs to match the learning task at hand to balance the number of network parameters with the available data, the complexity of feature interactions, and the noise that is introduced by unnecessary complexity.

We have found that the effects of convolutional neural network structure on its performance are task-specific. In both the motif learning and motif occupancy task, we observed that deploying more convolutional kernels is always beneficial. However the use of local-pooling and additional convolutional layers only help in our motif occupancy task when higher-order features exist.

We have demonstrated an improvement over the performance of DeepBind by a systematic exploration of convolutional neural network architectures, and thus our work suggests that using a configurable network approach will be important for sequence-based tasks in genomics. We have produced a flexible method of testing a wide variety of convolutional network architectures for the community and expect that this testing-based approach will prove useful for the further application of convolutional neural networks to genomics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the insightful suggestions from Tatsunori Hashimoto. We also acknowledge the helpful comments from other members of the Gifford laboratory.

Funding

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health under grants 1U01HG007037 and 5P01NS055923 and an equipment grant from NVIDIA.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Alipanahi B. et al. (2015) Predicting the sequence specificities of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins by deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol., 33, 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T.L. et al. (2009) MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res., 37, W202–W208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein B.E. et al. (2012) An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature, 489, 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandi M. et al. (2014) Enhanced regulatory sequence prediction using gapped k-mer features. PLoS Comput. Biol., 10, e1003711.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y. et al. (2014) Caffe: Convolutional architecture for fast feature embedding. arXiv Preprint arXiv, 1408, 5093. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky A. et al. (2012) Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Le Q.V. (2013) Building high-level features using large scale unsupervised learning. In: 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), IEEE, pp. 8595–8598.

- LeCun Y. et al. (2015) Deep learning. Nature, 521, 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainath T.N. et al. (2013) Deep convolutional neural networks for lvcsr. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), IEEE, pp. 8614–8618.

- Salakhutdinov R. (2015) Learning deep generative models. Ann. Rev. Stat. Appl., 2, 361–385. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N. et al. (2014) Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res., 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Tompson J. et al. (2014a) Efficient object localization using convolutional networks. arXiv Preprint arXiv, 1411, 4280. [Google Scholar]

- Tompson J.J. et al. (2014b). Joint training of a convolutional network and a graphical model for human pose estimation. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 1799–1807.

- Whitaker J.W. et al. (2015) Predicting the human epigenome from DNA motifs. Nat. Methods, 12, 265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Troyanskaya O.G. (2015) Predicting effects of noncoding variants with deep learning-based sequence model. Nat. Methods, 12, 931–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.