Abstract

Motivation: Transposable elements (TEs) and repetitive DNA make up a sizable fraction of Eukaryotic genomes, and their annotation is crucial to the study of the structure, organization, and evolution of any newly sequenced genome. Although RepeatMasker and nHMMER are useful for identifying these repeats, they require a pre-compiled repeat library—which is not always available. De novo identification tools such as Recon, RepeatScout or RepeatGluer serve to identify TEs purely from sequence content, but are either limited by runtimes that prohibit whole-genome use or degrade in quality in the presence of substitutions that disrupt the sequence patterns.

Results: phRAIDER is a de novo TE identification tool that address the issues of excessive runtime without sacrificing sensitivity as compared to competing tools. The underlying model is a new definition of elementary repeats that incorporates the PatternHunter spaced seed model, allowing for greater sensitivity in the presence of genomic substitutions. As compared with the premier tool in the literature, RepeatScout, phRAIDER shows an average 10× speedup on any single human chromosome and has the ability to process the whole human genome in just over three hours. Here we discuss the tool, the theoretical model underlying the tool, and the results demonstrating its effectiveness.

Availability and implementation: phRAIDER is an open source tool available from https://github.com/karroje/phRAIDER.

Contact: karroje@miamiOH.edu or

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Transposable elements (TEs) are genomic sequences that had (or have) the capacity to insert themselves, or copies of themselves, into other genomic locations. Present in almost every higher order genome, and covering as much as 45% of the human genome and 90% of the maize genome (Lander, 2001; SanMiguel et al., 1996), TEs have proved an important source of data in numerous studies of genomic structure (Arndt and Hwa, 2005; Karro et al., 2008; Mugal et al., 2008). They are also frequently a source of noise that needs to be masked. Unfiltered TEs can disrupt annotation tools, resulting in large false positive rates when subjected to automated gene finding tools, as well as inflated runtimes for the annotation tools (Jiang, 2013).

The most commonly used tools for repetitive DNA identification, such as RepeatMasker and nHMMER (Smit et al., 2015; Wheeler and Eddy, 2013), use precompiled descriptions of sequences in the family (e.g. an ancestral sequence or profile HMM) to aid in the identification of more instances of that family. But much like the question ‘How does the snow plow driver get to work?’ (Pratchett, 2006), we might ask how these libraries are compiled. RepeatMasker requires these libraries to work, but we cannot use RepeatMasker to generate them.

Initial libraries were compiled as a result of wet-lab work, using TEs identified through sequencing and biological study (McClintock, 1950; Sanger and Coulson, 1975). In the era of Bioinformatics, we would prefer an automated solution. When first examining a newly sequenced genome we can frequently rely on a library already compiled for a closely related genome, if such a genome has already been sequenced and annotated. Within mammals this works well, as such genomes are usually available. In plants we are less likely to find a well-sequenced organism of sufficiently close evolutionary distance to be of use. For example, a rice-based TE library will only lead to the identification of 25% of the TEs in the maize genome (Jiang, 2013). Thus the need for tools which do not require pre-compiled libraries to perform the initial analysis, or de novo TE identification tools.

The de novo TE identification tools in the literature are described and compared in both Saha et al. (2008) and Jiang (2013). Approaches to the problem vary, but generally fall into the following categories: k-mer searches [e.g. ReAS and RepeatScout (Li et al., 2005; Price et al., 2005)], self-alignment techniques [e.g. RECON and PILER (Bao and Eddy, 2002; Edgar and Myers, 2005)], and variants of DeBrujin Graphs (RepeatGluer; Pevzner et al., 2004; Zhi et al., 2006). In their testing, both Saha et al. (2008) and Jiang (2013) found RepeatScout to be the best tool overall for assembled genomes, and we will thus use it as the basis for comparison in assessing our tool.

1.1 Elementary repeats

Zheng and Lonardi approached the de novo identification problem using elementary repeats (Zheng and Lonardi, 2005). Similar to the RepeatGluer domains, elementary repeats are decompositions of TEs into basic ‘building blocks’. Although it is notoriously difficult to mathematically model TEs (Bao and Eddy, 2002), elementary repeats allow for an exact formal description. Specifically:

Definition 1 —

(Z&L). For given integer parameters l and f, a sequence ρ is an elementary repeat with respect to l and f in genome G if it conforms to the four requirements:

Structure: ρ is at least length l.

Frequency: There are at least f copies of ρ properly contained in G.

Minimality: There is no proper substring of ρ of at least length l that appears in G independently of ρ.

Maximality: There is no string such that every instance of ρ in the genome is contained in an instance of.

In short: an elementary repeat has no (sufficiently) long substrings that appear independently in the genome, and is not itself a component of any larger sequence meeting the requirements.

Zheng and Lonardi (2005) developed an identification algorithm with a runtime quadratic in the size of the scanned genome. This was refined to linear time by both He (2006) and by Huo et al. (2009) using suffix tree variations, but these approaches are limited in their ability to handle changes in the sequence that have occurred over time from accumulated substitutions and other changes at the base level.

Our goal is to (i) devise an elementary repeat identification algorithm that is both faster and more robust to base changes; and (ii) demonstrate the utility of elementary repeats in TE identification. Our initial tool, RAIDER, was a prototype that improved speed with mixed results in its effect on quality (Figueroa et al., 2013; Figueroa, 2013). Here we discuss phRAIDER, a new version of RAIDER which improves sensitivity by incorporating the PatternHunter spaced seed concept (Li et al., 2004) into its identification algorithm. The resulting algorithm maintains a 10× speedup on human chromosomal sequences, dropping the runtime on human chr. 1 from 70 min using RepeatScout to 8 min for phRAIDER.

2 Approach

In this section, we define a model for elementary repeats in the context of PatternHunter spaced seeds, a formalization of the ideas first proposed by Figueroa et al. (2013) and Figueroa (2013). Following this, we describe our algorithm, defined in detail in our Supplementary appendix, and evaluate its effectiveness in identifying TEs in the following section.

2.1 Spaced seeds

A spaced seed is a binary string used to specify a ‘match pattern’ (Li et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2002). Recall that when BLASTing (Altschul et al., 1997) a nucleotide sequence against a database, the first step is to find all sequences in the database that share a substring of a fixed length with the query sequence. The insight of Ma et al. underlying PatternHunter is that sensitivity can be improved, without a significant increase in runtime, by looking for a longer common substring with mismatches allowed at certain specified positions. For example, instead of looking for an exact shared substring of length 12, we might look for a substring of length 13 that was allowed to mismatch in the seventh base—represented by the ‘match string’, or seed, 1111110111111. (Indicating six required matches, an ignored base and six required matches.) Any binary pattern can specify a seed, and with the right seed (or set of seeds), Ma and Li (2007) and Ma and Yao (2009) have shown that the number of false negatives is significantly reduced without a major effect on false positives. However, working with seeds is a computationally challenging problem in terms of seed evaluation and optimal seed selection.

2.2 Model

Our goal is to redefine the concept of TEs to accommodate a spaced seed strategy. We will start here with a sketch of our theoretical model, and include a more detailed description in the Supplementary appendix. But we first need to introduce some terminology:

A sequence descriptor is a string over the alphabet, where * serves as a wild-card character. A nucleotide sequence g is consistent with a sequence descriptor r of the same length if g matches r in all positions where r does not have a *. A seed s is consistent with a sequence descriptor r of the same length if s has a 0 at all positions in which r has a * character.

Given a seed s of length l and a sequence descriptor r of length ≥ l, we can decompose r w.r.t. s if we can break r into a set of overlapping length l substrings such that every substring is consistent with s and every base position of r is included in at least one of the substrings.

The sequence decomposition of r w.r.t. s is created by taking the substrings of r covered by s, replacing those bases that match to a 0 with a *, and creating a set of the results. (The decomposition is undefined if r cannot be decomposed w.r.t. s.)

For example, given the seed s = 11011:

If r= AAAAA*GGGGG, then the decomposition of r w.r.t. s is {AA*AA, AA*GG, GG*GG}.

If r= AAAAA**GGGGG, then it is not decomposable with respect to s, as there is no substring consistent with s that contains either of the * characters.

We can now modify the previous definition of elementary repeats as follows:

Definition 2 —

(Seeded Elementary Repeats). Given a genomic sequence G, an integer f, and a spaced seed s, a sequence descriptor ρ describes an elementary repeat if it meets the four (modified) requirements of an elementary repeat:

Structure: ρ can be decomposed with respect to s.

Frequency: There are at least f substrings of G that are consistent with ρ.

Minimality: For every string t in the decomposition of ρ w.r.t. s, t appears in the genome only as a part of a string consistent with ρ.

Maximality: There is no sequence descriptor of ρ that both contains ρ as a proper substring and satisfies the previous three conditions.

Given a sequence descriptor ρ describing an elementary repeat, the elementary repeat family is the set of substrings in G that are consistent with ρ. The new definition encompasses the old, as shown by the theorem proved in the Supplementary appendix:

Theorem 1. —

When the seed s has no 0 characters, this definition of elementary repeats is equivalent to the Z&L definition where l is the length of the seed.

A proof for this theorem is presented in the Supplementary appendix.

3 Methods

3.1 phRAIDER algorithm

The phRAIDER algorithm takes a genome G and a single fixed seed s of length l and performs a one-pass scan of G (with an optional preliminary pass to reduce memory requirements). While scanning, we maintain the following data structures:

H: A (hash-table) mapping of sequence descriptors to the coordinate positions at which they have been seen.

Q: A queue containing potential families we have encountered in the last l bases.

A family structure holds an ordered list of sequence descriptors that comprise the decomposition of some sequence descriptor r w.r.t. s. At the end of the algorithm the set of families will exactly describe the elementary repeat elements in G.

A pseudocode-form version of our algorithm is contained in the Supplementary appendix, and here we give a high level description. In our scan, when we reach coordinate i we do the following:

Knock off the front family in Q if its last seen sequence descriptor starts more than l bases before i.

Take the length l substring at Gi, seed it (replace bases matching to a 0 in s with a *) to create v, and update the hash table entry H[v] to add i to the list of coordinates at which v begins.

-

Now we consider what effect v has on our list of putative families:

If this is the first occurrence of v, it is not yet known to be part of a family.

If this is the second occurrence of v, either it overlaps a family, or it is potentially the start of a new family:

If v overlaps the family F in Q and has the same offset from the start of the second instance of F that the first instance of v has from the first instance of F’s first l-mer, then mark it as a part of the (potential) family.

Otherwise, create a new family consisting only of l-mer v—the first l-mer in this family—and add it to Q.

- If v has been seen three or more times, then either:

- ○ v is the next l-mer in a family F we are currently expanding: create F and add it to the back of Q.

- ○ v is the first l-mer in some family: add F to the back of Q.

- ○ v is a member of some family: but not the first l-mer. Our putative family F violates maximality, and needs to be split into two families.

We end with a cleanup step to eliminate families that do not meet the frequency threshold. That is, do not occur at least f times in the genome.

Theorem 2. —

For a genome G, a seed s and a frequency threshold f, the phRAIDER algorithm will identify all sequences corresponding to any elementary repeat family (w.r.t. to s) in G.

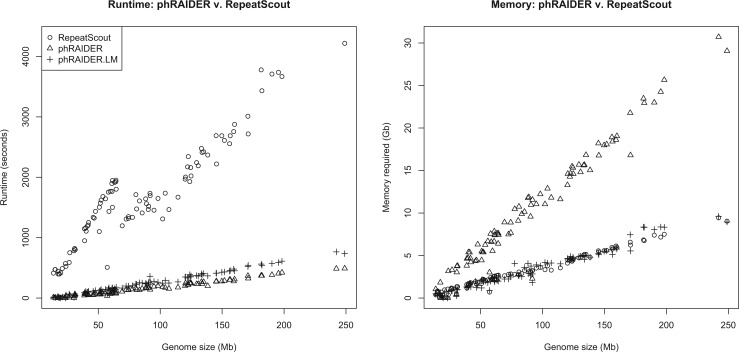

A proof is outlined in the Supplementary appendix. We also derive a worst-case runtime bound of O(n · s), where n is the size of the genome and s is the size of the seed. Since the seed is generally both short (<100 bases) and fixed, this leaves the algorithm as linear in the size of the genome—consistent with our empirical result from Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Runtime and memory usage for each tool, shown as a function of genome size for all autosomes from human, dog, mouse and C. elegans. All runs were on a single core of a 12 core Intel Xeon x5650 CPU with 48 GB memory on equipment at the Ohio Supercomputer Center (Center, 1987). On the full human genome phRAIDER.LM (which reduces memory requirements with a preliminary scan of the genome) required 3 h 7 min; RepeatScout was unable to complete due to a documented memory error

4 Results

In this section we both explore the response of phRAIDER to changes in seed (Fig. 3), and compare the performance of phRAIDER against that of RepeatScout, using chromosomes selected from Caenoharbditis elegans, arabidopsis, mouse, dog and human. Performance is measured in terms of resource usage: runtime and memory consumption, which are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. We then measure result quality based on the metrics described below. Figure 3 shows response to seed change, and Table 1 compares result quality against other tools.

Fig. 3.

Variation in sensitivity due to seed length and seed density on (simulated) C. elegans chromosome 5. Specificity is near perfect (≥98%) in all cases, and not shown here. Triangles represents the masking metric, circles the RepeatMasker metric and horizontal lines the RepeatScout results fore each metric (dotted = masking, dashed = RepeatMasker). Length is the number of characters in a seed; weight is the number of 1s in a seed. Density is the weight-to-length ratio. For seeds with density <1, weight was fixed at 32, with seeds chosen randomly within that constraint

Fig. 2.

Effect of seed weight and length on resource usage. We see seed weight (number of 1 characters) has significant effect on both runtime and memory, while density has a small effect on memory. The stepped nature of the memory-to-length plot is an effect of the use of the C ++ standard template library unordered map data structure, and its strategy of occasionally increasing the table size by large amounts

Table 1.

Improvement of RAIDER over RepeatScout as measured by masking-based sensitivity, as well as RepeatMasker-based sensitivity

| Seed | Organism | Simulation | Simulation | Masking | RM-based | phRaider | RptScout | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | basis | size | Sensitivity | Sensitivity | runtime | runtime | ||

| (Mb) | (v. RS) | (v. RS) | (seconds) | (seconds) | ||||

| Seeds selected to optimize Masking Sensitivity | ||||||||

| 537 | arabidopsis | chr5 | 2.91 | 0.51 | 0.06 | 1 | 26 | 260 |

| 516 | C. elegans | chrI | 4.01 | 0.11 | −0.11 | 1 | 120 | 1201 |

| 545 | C. elegans | chrII | 3.18 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 2 | 73 | 730 |

| 489 | C. elegans | chrIII | 3.75 | 0.11 | −0.13 | 1 | 114 | 1143 |

| 536 | C. elegans | chrIV | 3.63 | 0.11 | −0.09 | 1 | 117 | 1179 |

| 480 | C. elegans | chrV | 4.90 | 0.14 | −0.02 | 1 | 252 | 2522 |

| 512 | human | chr22 | 22.94 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 41 | 474 | 114 |

| 545 | mouse | chr19 | 32.15 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 47 | 2319 | 491 |

| Seeds selected to optimize RepeatMasker sensitivity | ||||||||

| 537 | arabidopsis | chr5 | 2.99 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1 | 26 | 260 |

| 154 | C. elegans | chrII | 3.21 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 1 | 73 | 730 |

| 154 | C. elegans | chrIV | 3.66 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 1 | 117 | 1175 |

| 70 | C. elegans | chrIII | 3.75 | 0.04 | −0.1 | 1 | 114 | 114 |

| 262 | C. elegans | chrI | 4.03 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 1 | 120 | 1209 |

| 262 | C. elegans | chrV | 4.90 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 1 | 252 | 2521 |

| 508 | human | chr22 | 37.96 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 29 | 474 | 164 |

| 262 | mouse | chr19 | 42.25 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 57 | 2319 | 401 |

| 537 | human | chr18 | 43.11 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 71 | 1412 | 191 |

| Single seed picked for balance on all organisms | ||||||||

| 262 | arabidopsis | chr5 | 2.99 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1 | 26 | 260 |

| 262 | C. elegans | chrII | 3.21 | 0.1 | −0.02 | 1 | 73 | 730 |

| 262 | C. elegans | chrIV | 3.66 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 1 | 117 | 1176 |

| 262 | C. elegans | chrIII | 3.75 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 1 | 114 | 1141 |

| 262 | C. elegans | chrI | 4.03 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 1 | 120 | 1209 |

| 262 | C. elegans | chrV | 4.90 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 1 | 252 | 2521 |

| 262 | human | chr22 | 37.96 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 37 | 474 | 124 |

| 262 | human | chr18 | 42.25 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 85 | 1412 | 161 |

| 262 | mouse | chr19 | 43.11 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 57 | 2319 | 401 |

Specificity is near identical (≥98%) in all cases. The seed index is an arbitrarily assigned index of the seed (see Supplementary appendix). Seeds were chosen by using the best from a small random sampling over a range of weights and lengths.

4.1 Resource usage

We assessed phRAIDER against RepeatScout (Price et al., 2005), designated the leading TE identification tool by Saha et al. (2008) and Jiang (2013). We found that phRAIDER gives significant runtime speedup over RepeatScout: an average 10× speedup for individual human chromosomes, dropping runtime from 70 to 8 min on human chr. 1 and completing a whole-genome run in 3 h 7 min. RepeatScout could not complete a whole-genome run on the human genome due to a memory error—a problem acknowledged in the RepeatScout documentation (Price et al., 2005).

All testing was done on chromosome sequences obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser (Kent et al., 2002) for C. elegans, mouse, dog and human, and the TAIR browser (Berardini et al., 2015) for arabidopsis. Figure 1 illustrates runtime and memory usage for RepeatScout (ˆ symbols), phRAIDER (+ symbols), and a memory-efficient version of phRAIDER (Δ symbols). RepeatScout was run using default parameters, while phRAIDER used one of the selected seeds from the next section. phRAIDER is clearly memory intensive, which is primarily due to the necessity of storing every genomic coordinate in the hash table. We can alleviate this with a preliminary pass over the genome that allows us to filter out unique sequence descriptors without changing our results. We see that while this adds a small amount of runtime, both versions are significantly faster than RepeatScout, and the memory-efficient version is comparable to RepeatScout in memory usage.

In Figure 2 we see the effect of varying seed length and density on resource usage; the results are unsurprising.

4.2 Quality metrics

We evaluate the quality of tool results using two methods:

Masking metric: We tested the ability to selectively mask out repeat sequences. This is vital for the accurate performance of other genomic analysis tools. The sensitivity of each tool was determined by BLASTing (Altschul et al., 1997) the consensus sequence constructed from identified repeat against repeats listed in RepBase (Jurka et al., 2005).

RepeatMasker metric: We tested the utility of the toolit output as a library for RepeatMasker, allowing more comprehensive detection of TEs for those interested in TE sequences themselves. The sensitivity of each tool was determined by comparing the RepeatMasker output against the RepBase identified repeat sequences.

Note that, as RepBase annotations are a collection of results from many studies (Jurka et al., 2005), it is not realistic to expect any one tool to find a large portion of the results; sensitivity will not be high. What is important is the relative performance of the two tools—indicating which will do better on the first pass over a newly sequenced, or poorly studied, genome. Further, the applications of RepeatMasker for result analysis were computationally intensive, limiting the feasible size of test benchmarks. The problem is at least in part due to the large number of overlapping elementary repeats produced, and is one we expect to be alleviated with an assembly tool we currently have under development.

In all analyses we report only sensitivity. Specificity is near perfect (≥0.98%) using both tools on all data sets in all cases. In short: it is very easy to avoid false positives in this problem. The challenge is to avoid false negatives.

4.3 Synthetic chromosomes

For resource testing we used full, unaltered chromosome sequences. For quality testing we removed all TEs that occur only once, as no tool can identify them as repeats. We left all other TEs intact, and replaced inter-TE sequences with 1000 bp sequences generated using a fifth-order Markov chain derived from the actual chromosomal sequence. This method of generating simulated sequences, used by Saha et al. (2008), removes unannotated repeat sequences which could incorrectly increase our false positive count, and reduces input size while still requiring the tool to search for actual TEs. The result is a ‘semi-synthetic’ sequence: one that is reduced in size, but still accurately reflects the important characteristics of an actual sequence.

4.4 Quality of results

Although phRAIDER is significantly faster than RepeatScout, that is only of value if the quality of the results is at least comparable with that of alternative tools. There is also the question of the effect of the spaced seed selection on result quality—do they make a difference, and if so, what are the optimal values? In the following we use a C. elegans chr. V-based synthetic chromosome to investigate the effect of parameter modification, then compare the output of phRAIDER against RepeatScout on selected chromosomes from C. elegans, arabidopsis, mouse and human. Although phRAIDER is fast enough to allow for large-scale testing on real chromosomes, the runtime required for the RepeatMasker analysis of the results precluded this approach on a chromosome scale—forcing us to use smaller semi-synthetic sequences.

In PatternHunter, choice of seed has a significant effect on result quality in homology-based search. Li et al. (2004) report that in one case, the choice of seed can improve hit rate from under 30% to over 80%. However, finding the optimal seed is a computationally challenging problem (Ma and Li, 2007). Our first goal is to verify that seeds are also useful in de novo identification, and that their structure had an impact on the results. We characterize our seeds with three variables: length l is the number of characters in a seed, weight w is the number of 1 characters in a seed, and density , where d = 1 indicates a seed with no wild-card characters.

In Figure 3 we see the effect of varying seed length when density is held at 1 (that is, no zero characters), as well as the effect of varying density while holding weight at 32 (using a small number of randomly picked seeds at each density). In each case, triangles represents our masking metric, circles our RepeatMasker metric, and the horizontal lines indicate RepeatScout performance using default parameters (dotted is masking, dashed is RepeatMasker). We see from these results that seeds do impact result quality. It is also evident that while length and density are factors in determining a good seed, they are not sufficient in themselves to find optimal seeds. Due to the runtime constraints of our analysis software we were limited to randomly exploring a minuscule portion of the seed space, leaving significant potential for improvement. Finding good seeds will require greater resources or the development of an analytic approach, which is beyond the scope of this work, and currently under development in our lab.

Table 1 displays the results from our random exploration of the seed space. In the first section of the table we see the best seed for each tested chromosome, based on a sample of a few hundred randomly picked seeds, shown in terms of their improvement over the RepeatScout baseline tool (e.g. on ce10 chrV phRAIDER sensitivity is 14% higher than RepeatScout). In this table we see that results are somewhat dependent on seed choice. But in general we see an improvement in the ability to mask, a range of results in using the output as a RepeatMasker library, and a speedup of several orders of magnitude.

5 Conclusion

phRAIDER is a new tool for the de novo identification of genome repeat elements that is applicable to assembled genomes. We have empirically demonstrated that it is orders of magnitude faster than the premier tool in the literature (RepeatScout) yet still improves on that tool’s ability to mask out TEs and other genomic repeats. Specifically: we have developed a formal mathematical model combining the concept of spaced seeds with that of elementary repeats; in addition we have implemented a tool around this model, and we have used that tool to demonstrate that:

The identification of elementary repeats is useful in the context of de novo repeat masking.

The introduction of spaced seeds improves results without significant adverse effects on runtime.

The resulting tool produces results of a quality on par with the leading tool in the literature but works at a speed significantly faster (with an average 10× speedup over RepeatScout for the human chromosome).

We have produced a freely available implementation of phRAIDER distributed from https://github.com/karroje/phRAIDER under the GNU General Public License (version 3). All code is implemented in C ++ and tested on OS X and various flavors of Linux. The tool will provide a list of elementary repeats with the coordinates of each instance, and will optionally produce a masked genomic sequence.

phRAIDER is the first step towards a full identification tool for TEs and repetitive DNA, but leaves considerable room for improvements. The use of multiple spaced seeds has been highly successful in other applications and we are in the process of implementing this—but doing so requires modifications to both the algorithm and the underlying theoretical model, and is beyond the scope of this work. We are also developing tools to aid in seed selection, and to assemble elementary repeats into contiguous TEs—thus implicitly addressing the problems with indels as well. Preliminary tests indicate that this last improvement, while not significantly increasing computation time, will considerably improve phRAIDER’s performance in generating RepeatMasker libraries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Laura Tabacca, Luke Skon, Craig Lovell and Greg Gelfond for their help with manuscript preparation.

Funding

This research was conducted under funding from the National Science Foundation grant 0953215.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Altschul S. et al. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt P.F., Hwa T. (2005) Identification and measurement of neighbor-dependent nucleotide substitution processes. Bioinformatics, 21, 2322–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Z., Eddy S.R. (2002) Automated de novo identification of repeat sequence families in sequenced genomes. Genome Res., 12, 1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardini T.Z. et al. (2015) The arabidopsis information resource: making and mining the “gold standard” annotated reference plant genome. Genesis, 53, 474–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center O.S. (1987). Ohio supercomputer center. http://osc.edu/ark:/19495/f5s1ph73.

- Edgar R.C., Myers E.W. (2005) PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 21, i152–i158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa N. (2013). RAIDER: Rapid Ab Initio Detection of Elementary Repeats. Master: RThesis, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa N. et al. (2013). RAIDER: Rapid Ab Initio Detection of Elementary Repeats In Advances in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, pp. 170–180. Springer International Publishing, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- He D. (2006). Using suffix tree to discover complex repetitive patterns in DNA sequences. Conference proceedings: … Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual Conference, vol. 1, pp. 3474–3477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huo H. et al. (2009). An Adaptive Suffix Tree Based Algorithm for Repeats Recognition in a DNA Sequence. 2009 International Joint Conference on Bioinformatics, Systems Biology and Intelligent Computing. Shanghai, China, pp. 181 –184.

- Jiang N. (2013) Overview of repeat annotation and de novo repeat identification. Methods Mol. Biol., 1057, 275–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J. et al. (2005) Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res., 110, 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karro J.E. et al. (2008) Exponential decay of GC content detected by strand-symmetric substitution rates influences the evolution of isochore structure. Mol. Biol. Evol., 25, 362–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W.J. et al. (2002). The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome, 12, 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E.S. et al. (2001) Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature, 409, 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. et al. (2004) Patternhunter II: highly sensitive and fast homology search. J. Bioinformatics Comput. Biol., 2, 417–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. (2005) ReAS: Recovery of ancestral sequences for transposable elements from the unassembled reads of a whole genome shotgun. PLoS Comput. Biol., 1, e43.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B., Li M. (2007) On the complexity of the spaced seeds. J. Comput. Syst. Sci., 73, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Ma B., Yao H. (2009) Seed optimization for i.i.d. similarities is no easier than optimal Golomb ruler design. Inform. Process. Lett., 109, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Ma B. et al. (2002) PatternHunter: faster and more sensitive homology search. Bioinformatics, 18, 440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. (1950) The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 36, 344–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugal C.F. et al. (2008) Transcription-induced mutational strand bias and its effect on substitution rates in human genes. Mol. Biol. Evol., 26, 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevzner P.A. et al. (2004) De novo repeat classification and fragment assembly. Genome Res., 14, 1786–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratchett T. (2006). Hogfather: A Novel of Discworld. HarperPrism, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Price A.L. et al. (2005) De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics, 21, i351–i358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S. et al. (2008) Empirical comparison of ab initio repeat finding programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 36, 2284–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Coulson A.R. (1975) A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol., 94, 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel P. et al. (1996) Nested retrotransposons in the intergenic regions of the maize genome. Science), 274, 765–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A.F.A. et al. (2015). RepeatMasker Open 4.0. 2013–2015. http://www.repeatmasker.org.

- Wheeler T.J., Eddy S.R. (2013) nhmmer: DNA homology search with profile HMMs. Bioinformatics, 29, 2487–2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Lonardi S. (2005). Discovery of Repetitive Patterns in DNA with Accurate Boundaries. Fifth IEEE Symposium on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBEame), pp. 105–112

- Zhi D. et al. (2006) Identifying repeat domains in large genomes. Genome Biol., 7, R7.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.