Abstract

Motivation: Unraveling the molecular mechanisms that underlie disease calls for methods that go beyond the identification of single causal genes to inferring larger protein assemblies that take part in the disease process.

Results: Here, we develop an exact, integer-programming-based method for associating protein complexes with disease. Our approach scores proteins based on their proximity in a protein–protein interaction network to a prior set that is known to be relevant for the studied disease. These scores are combined with interaction information to infer densely interacting protein complexes that are potentially disease-associated. We show that our method outperforms previous ones and leads to predictions that are well supported by current experimental data and literature knowledge.

Availability and Implementation: The datasets we used, the executables and the results are available at www.cs.tau.ac.il/roded/disease_complexes.zip

Contact: roded@post.tau.ac.il

1 Introduction

The association of genes with disease is a fundamental problem with important medical applications. Gene prioritization techniques are based on different types of data ranging from sequence and homology information to function and molecular interactions (see Bromberg, 2013 for a review). State-of-the-art methods for prioritization employ protein–protein interaction (PPI) information, based on the empirical finding that genes that cause similar diseases tend to lie close to one another in the PPI network. Many methods have been developed following this reasoning. Lage et al. (2007) score a candidate gene in a linkage interval according to the clinical overlap between the phenotypes associated with its interactors and the disease in question. Köhler et al. (2008) perform a random walk on the PPI network, starting at the known disease genes, and rank candidate genes by the steady state probabilities induced by the walk. Vanunu et al. (2010) apply a propagation algorithm that starts at causal genes, weighted by the phenotypic similarity of the disease they cause and a query disease, and compute a strength-of-association function that is smooth over the network. Magger et al. (2012) focused on the tissue where a given disease is manifested and executed the same propagation algorithm over a tissue-specific network that was inferred by gene expression data.

Another approach for performing gene prioritization is via inference from existing functional annotations. For example, Schlicker et al. (2010) rank candidate genes by the semantic similarity of their GO annotations (The Gene Ontology Consortium, 2000) to the GO terms associated with the known disease genes. This approach, however, relies on the availability of gene annotations and thus could miss related genes with yet unknown function. A related line of works relies on the description and comparison of phenotypes using ontologies (Robinson et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2005). In particular, Hoehndorf et al. (2011) computed all the pairwise similarities between phenotypes in several organisms as well as phenotypes associated with human diseases. A model organism phenotype that exhibits high similarity to a human phenotype may suggest the corresponding genotype as a candidate for the human disease. Robinson et al. (2014) integrated this approach with exome sequence analysis by considering both the phenotypic relevance of a gene as well as evidence from its sequence reflecting the rarity and pathogenicity of the gene’s variants.

Despite the availability of numerous methods for exposing the genomic basis underlying human diseases, most of these methods are limited to the discovery of individual genes. Many studies, however, link diseases to dysfunctions of assemblies of proteins working in concert. A well-known example is the Leigh syndrome, an inherited neurometabolic disorder caused by deficiencies in mitochondrial complexes (Amberger et al., 2009) (MIM no. #256000). Cancer related complexes were reported by Kadoch et al. (2013) and Santidrian et al. (2013). Therefore, a more systematic understanding of certain disorders could be achieved by looking directly for related protein complexes rather than focusing on single proteins (Zhao et al., 2013). Several papers have approached this problem from a computational view. Vanunu et al. (2010) apply their propagation algorithm to mark potential disease related proteins, and then look for high scoring protein complexes, measured in terms of the specificity of their interactions with respect to a random model. The HotNet2 algorithm of Leiserson et al. (2015) considers mutated genes across cancer patients, looking for significantly mutated subnetworks. To this end, from each such gene HotNet2 diffuses heat over the PPI network, yielding a diffusion matrix or a weighted digraph. The strongly connected components of this digraph are the inferred ‘hot’ subnetworks. Finally, the MAXCOM method of Chen et al. (2014) scores candidate complexes from CORUM (Ruepp et al., 2010) by computing the maximum flow from a query disease to a target complex in an integrated network combining disease-disease similarities, disease-gene associations and PPIs.

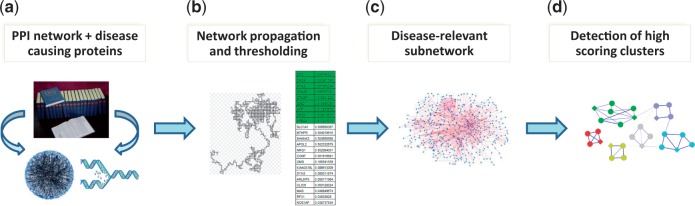

In this paper we address the problem of protein complex detection by devising a framework that integrates network propagation with a novel integer program algorithm designed to discover dense clusters with highly specific interactions. The outline of the framework is depicted in Figure 1. We test our framework by computing protein clusters for tens of diseases and compare our predictions to those of two leading tools for subnetwork detection, PRINCE (Vanunu et al., 2010) and HotNet2 (Leiserson et al., 2015). We show that the clusters produced by our method are both denser and more biologically relevant. We also present expert analyses for two diseases—epilepsy syndrome and intellectual disability, demonstrating the ability of our algorithm to find relevant disease clusters as well as to predict novel disease protein associations.

Fig. 1.

The protein complex detection framework. (a) Disease causing proteins and PPI data are retrieved from the literature. (b) Network propagation is executed starting at the causal proteins of a certain disease, yielding a ranked list of proteins which is then filtered using an empirical-based P-value. (c) Likelihood scores are assigned to all network PPIs, designed to prefer interactions that are more likely to appear in a protein complex model compared to a random model. The input for the detection phase is the weighted subnetwork induced by the proteins that passed the filtering. (d) High scoring clusters are detected using an integer linear programming algorithm

2 Materials and methods

The computational framework we have devised works in two conceptual phases: (i) identification of network regions that are potentially associated with the disease under study; and (ii) inference of densely interacting protein clusters within those regions. We describe these phases in detail in the sequel.

2.1 Constructing a disease-relevant subnetwork

As we look for complexes that are related to a certain disease, we wish to focus on network regions surrounding proteins that are already known to be associated with the disease. To find such regions, we follow the approach of Vanunu et al. (2010) and apply a network propagation algorithm that starts at the known disease-causing (prior) proteins, and ranks all other network proteins by computing their propagation scores. Formally, given a network , a normalized weight function and a prior knowledge function , we seek a function that both respects the prior knowledge and is smooth over the network. Denoting the set of neighbours of v by N(v), F is expressed as follows:

The function F can be computed accurately using simple linear algebra, but can be more efficiently approximated using an iterative procedure.

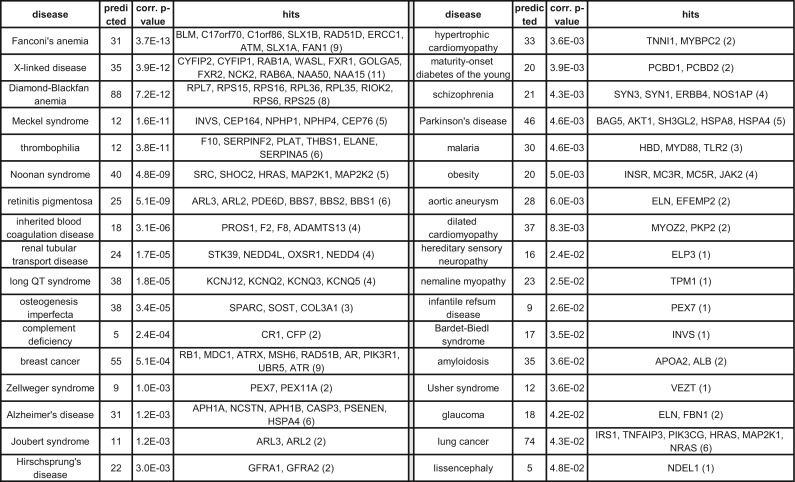

To select the most relevant proteins from the ranked list, we first note that for different prior sizes, the propagation function assigns scores of different magnitudes: the smaller the prior size, the faster the scores drop to 0. For example, on random priors of sizes 10, 25 and 100, the 200th largest score has a mean of 0.002, 0.006 and 0.018, respectively (with standard deviations around 0.001), over 10 executions (with respect to the PPI network presented below). This is illustrated in Figure 2. Therefore, we sought to devise a normalization method that resolves this bias.

Fig. 2.

Score distribution of the propagation function. This figure shows the top 1000 propagation scores for different prior sizes (100, 25, 10, from left to right), excluding prior nodes. Each subplot shows results from 10 random executions. Clearly, the smaller the prior size, the faster the function converges to 0

Given a prior set of genes and the corresponding propagation distribution, we executed the propagation algorithm 1000 times over random sets of the same size. For each gene, we ranked its real score with respect to its scores on the random data (excluding the random instances where that gene was selected for the prior). This provides a P-value for every gene, allowing us to focus on the significant ones (a threshold of 0.01 is used in the sequel).

2.2 Detection of protein complexes

Given an initial network G and a disease-related subnetwork , we wish to find highly interacting protein sets within H. To this end, we follow the scheme of Vanunu et al. (2010) and define the score of a protein set C as the log likelihood ratio between a protein complex model, in which every two proteins in a complex interact with some high probability β (set to 0.9, results are robust in the range 0.8–0.95), and a random model which assumes that interactions in the input network occur at random with a probability proportional to the proteins’ degrees. Denote by dv the degree of node v in G, and by t the number of edges in G. As the (approximate) probability of an interaction (i, j) to appear in a random degree-preserving network is , the likelihood score for an interaction (i, j) which participates in C is . Similarly, the likelihood score for a non-interaction between proteins i, j in C would be . Denote by and the sets of nodes and edges of C, respectively. The likelihood score of C is computed as:

To detect high scoring protein sets, we formulate an integer linear program (ILP) that makes use of two sets of variables. First, for each node , a binary variable vi will indicate whether i is part of the formed cluster. Second, we could now define for every a binary variable eij that indicates whether i and j are both in the formed cluster. The objective function would then be:

However, as the number of such variables is quadratic in , this would be a burden on the ILP performance. We therefore define eij variables only for edges rather than all node pairs, and estimate the penalty on missing edges as a constant , as we found L0 to be well approximated by it (in a network of 150 000 edges, when the geometric mean of di, dj varies between 2 and 100, ranges between −2.3 and −2.26).

The following integer program finds a highest scoring cluster:

s.t.:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The equalities 1 and 2 set R and T as the number of nodes and edges in the cluster, respectively. Constraint 3 stipulates that eij equals 1 if and only if both its endpoints were selected for the cluster. Constraint 4 requires that every cluster node be connected to at least half of the other cluster members, ensuring that the cluster’s diameter is at most two.

The above program is quadratic as it contains the term R2 in the objective function. To linearize it, we exploit the fact that the size of a real complex is typically no more than 20 (Vanunu et al., 2010). Thus, we can define a small set of if-then statements that determine R2. Assuming the cluster size R is in the range , the following constraints are added:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

Constraints 5 and 6 set the auxiliary binary variables gc and sc to 1 if and only if , or , respectively. Constraint 7 combines gc and sc to define ac = 1 if R = c, or otherwise ac = 0. Finally, as R must be equal to exactly one c in the range , the sum in 8 equals R2. Consequently, the term in the objective function can be replaced by the linear term .

It is worth noting that the above ILP is significantly faster than a naïve linearization approach that runs the basic quadratic program iteratively with R fixed in each iteration.

2.3 Implementation details and parameter selection

Following Vanunu et al. (2010), in the propagation phase we assigned similar weight () to the contribution of the prior data on disease genes versus the network topology and its confidence scores. The genes with the most significant propagation scores were chosen using a strict P-value cutoff of 0.01. The input network for the clustering phase was the PPI subnetwork induced by those genes. In the cluster detection phase, we used the likelihood scores described in Section 2.2, and excluded hubs with degree above 500. We instructed the ILP algorithm to find the top scoring cluster with size between 4 and 20, then removed its nodes from the network and iterated. We repeated this process 10 times or until no cluster could be found (typically due to the strict connectivity constraint 4 in the ILP).

3 Results

3.1 Gene–disease association retrieval

We collected high-quality disease–protein associations from several databases: OMIM (Amberger et al., 2009), OrphaData (Orphanet, www.orphadata.org) and DISEASES (Pletscher-Frankild et al., 2014). From the latter source we used only the ‘knowledge channel’ which contains manually curated associations from the Genetics Home Reference (Mitchell et al., 2006) and the UniProt Knowledgebase (The UniProt Consortium, 2014).

The unification of the data from the three databases required careful handling of several aspects. First, a common dictionary was required for disease identification. Second, different databases describe diseases in different resolutions. For example, the ALS disease has 20 subtypes in OMIM, each of which is associated with one or two genes; in the other two databases this disease is represented using only one to three subtypes. To handle the different standards, we categorized the diseases using the Disease Ontology (DO) (Schriml et al., 2012), which provides a hierarchical structure of diseases and groups of diseases. For each gene–disease association from one of the databases, we propagated it upstream through the ontology hierarchy. The linkage between DO terms and OMIM diseases was performed using an available mapping in the DO database; the integration with OrphaData was name based; the DISEASES database was already standardized with DO identifiers. Using these mappings, we extracted 2753 disease-gene associations from OMIM, 923 associations from OrphaData and 3887 associations from DISEASES, which in total span 1099 net disease terms, or 1546 terms after accounting for the ontology hierarchy. We removed terms with less than 10 genes or terms that are not directly associated to a gene in any of the databases and are located more than one level above some leaf node. To avoid redundancy, for each path from the root to some leaf we retained at most one term (the most specific). The final list contained 115 diseases.

3.2 Performance evaluation

We executed our algorithm on each of the tested diseases, providing it as input the disease’s prior genes (Section 3.1). Our input PPI network was retrieved from the HIPPIE database (Schaefer et al., 2012), filtered for its 148 441 medium or high confidence interactions, over 14 388 nodes. We compared the algorithm’s performance to two state-of-the-art methods for predicting disease associated protein subnetworks, PRINCE (Vanunu et al., 2010) and HotNet2 (Leiserson et al., 2015). In the PRINCE implementation, we used their suggested propagation score threshold of 0.015 to determine the set of genes to cluster. As HotNet2 is limited to returning subnetworks over its input genes only, we defined the input heat of a gene as a large constant c if it is a prior gene, and 1 otherwise; we tested two values for c, 10 and 1000, and obtained similar results, henceforth we report the results achieved with c = 10. A subnetwork produced by HotNet2 was considered significant if the empirical P-value reported for its size or any smaller size was less than 0.05.

Our ILP algorithm predicted 638 clusters, spanning all the 114 diseases that had at least one prior gene in the PPI network (the actual minimum prior size was 6). The PRINCE algorithm returned 402 clusters. Expectedly, the number of clusters that PRINCE generated per disease strongly depended on its prior set size (, Pearson correlation), while the correlation was much weaker for our algorithm (P < 0.03). This gap can be explained by the flexibility of our propagation P-value scheme, compared to the fixed cutoff approach of PRINCE. The HotNet2 algorithm generated 1215 clusters which cover only 26 diseases; this ratio was due to the behaviour of the statistical test, which in many cases failed to find any significant size while in other cases returned a small size, resulting in tens of subnetworks.

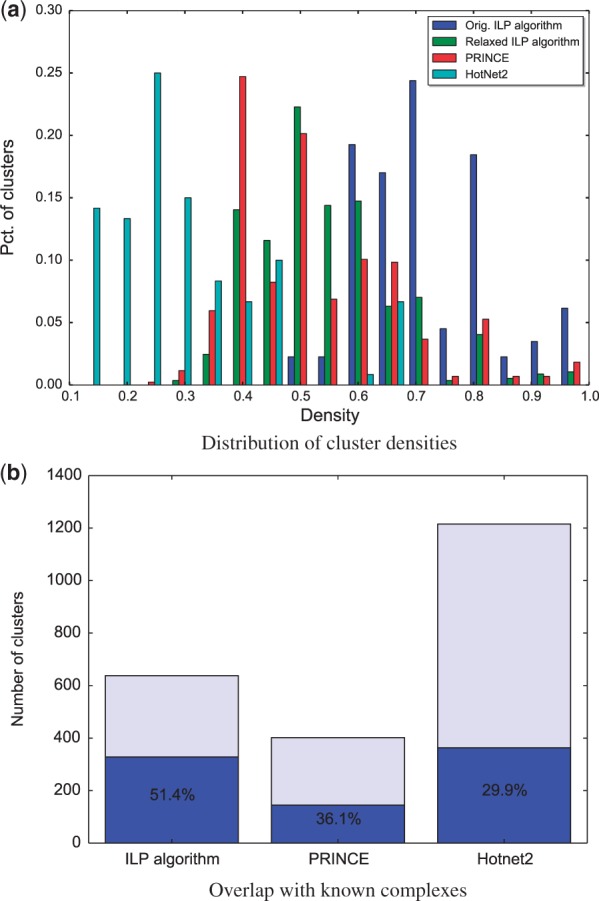

Next, we compared the densities of the clusters output by the different algorithms. The average density of a cluster produced by our algorithm was 0.72, calculated aggregatively over all 638 clusters (7697 edges versus 2984 non-edges). In comparison, the same statistic for PRINCE was 0.52, and for HotNet2 only 0.22 (likely due to the fact that HotNet2 captures also path-like patterns). We also compared the distributions of the individual cluster densities induced by the three algorithms. To account for the different number of clusters produced by each method, we limited the comparison to the top 5 clusters per disease (as HotNet2 provides no ranking, 5 arbitrary clusters of the smallest size were selected). Further, to account for the fact that constraint 4 in the ILP has an explicit positive effect on the density, we applied a variant that excluded it. The density values induced by our algorithm were significantly higher than those of PRINCE (, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Expectedly, the density values were also higher than those of HotNet2 (). The results are summarized in Figure 3(a).

Fig. 3.

Performance evaluation. (a) A comparison between the cluster density distributions (only top 5 clusters per disease) induced by our ILP algorithm, a relaxed variant of it without constraint 4, PRINCE and HotNet2. (b) A comparison of the percent of predicted clusters significantly overlapping a known complex, for each of the three methods

We further wished to test if our predicted dense clusters significantly overlap known biological complexes. To this end, we tested the overlap of each of the predicted clusters with 2276 known biological complexes that we collected from CORUM (Ruepp et al., 2010) and GO (The Gene Ontology Consortium, 2000) (GO data from Nov 2015). Out of the 638 predicted clusters, 328 (51%) had a statistically significant overlap with at least one complex, according to a hypergeometric test, corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). In comparison, only 145 of the PRINCE clusters (36%), and 363 of the HotNet2 clusters (30%) significantly intersected a curated complex (Fig. 3(b)).

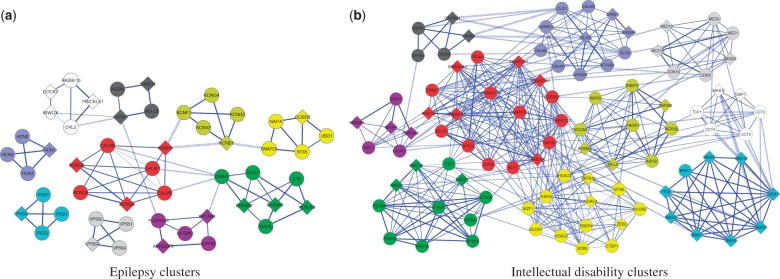

To validate that the predicted clusters are relevant for the diseases for which they were computed, we used independent sets of genes that we reserved for validation. We picked these validation genes from the text-mining and experimental channels in the DISEASES database (Pletscher-Frankild et al., 2014), which may be of lesser quality than those we used for the priors. The intersections between the ILP predicted genes (taken together over all clusters per disease, without the prior genes) and the validation sets for 34 out of 105 diseases (having some validation information) were statistically significant (FDR-corrected hypergeometric P-value < 0.05; Fig. 4). A similar analysis for PRINCE yielded 33 diseases with statistically significant intersections; interestingly, the two methods captured 21 common diseases, which implies that the methods somewhat complement each other. Finally, only two diseases in the output of HotNet2 were found significant, when considering only the 23 diseases with at least one cluster and non-empty validation sets; of these two, one disease was not enriched by any of the other methods (severe combined immunodeficiency), and another one was enriched by both methods (schizophrenia).

Fig. 4.

Enrichments of predicted disease genes. This table displays the statistically significant intersections between predicted disease clustering genes (taken together, without prior genes) and the corresponding validation sets. Per enriched disease, the number of predicted genes, the corrected p-value and the intersecting genes are shown

To compare the predictive power of the three algorithms for the remaining diseases (those for which the FDR was above 0.05), we tested whether the predicted genes were related to similar diseases. To this end, we used the pairwise disease similarities reported by Hoehndorf et al. (2015), which are based on phenotype identification using a text-mining approach. For each predicted gene in a disease d, we looked which of its associated diseases (extracted from both the prior and the validation data) is most similar to d, and recorded the maximal similarity score. We computed the average score over all the predicted genes for d and defined it as the score of d. We compared the score distributions as induced by the three algorithms. While the scores induced by our algorithm and by PRINCE were comparable, the scores of our algorithm were significantly higher than those of HotNet2, indicating that our predictions are more relevant in their context (, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

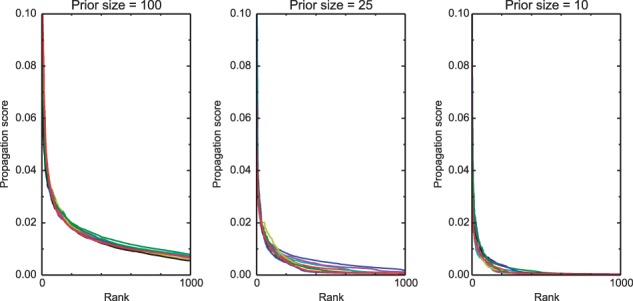

3.3 Biological case studies

After establishing the utility of our method, we applied it to carefully analyze two test cases for which we had expert knowledge. First, we executed our framework on a set of 97 proteins associated with the term ‘epilepsy syndrome’ from the Disease Ontology. This term is the root of a hierarchy of epilepsy subtypes, classified by age at onset, triggering factors, patterns of seizure and other criteria. Our algorithm predicted 10 clusters, displayed in Figure 5(a). The majority of these clusters are synaptic, consistent with the classification of epilepsy as a synaptopathy. The top ranked cluster (in red color) contains 7 proteins (with 17 internal interactions out of 21 possible ones), out of which three are from the prior, KCNH1, KCNQ2 and KCNQ3. Mutations in KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 have long been known to cause benign familial neonatal seizures (BFNS) (Biervert et al., 1998; Castaldo et al., 2002), with recent increasing evidence also for other types of epileptic diseases (Miceli et al., 2015; Weckhuysen et al., 2012). Proteins encoded by these genes form potassium channels that transmit electrical signals (called M-current) regulating neuronal excitability in the brain. Reduced or altered M-current may lead to excessive excitability of neurons, resulting in seizures. Mutations in KCNH1, another member of the voltage-gated potassium channel, have also been associated with epilepsy (Simons et al., 2015).

Fig. 5.

Predicted disease clusters for epilepsy and intellectual disability. These figures show the top ten ranked clusters predicted to play a role in (a) epilepsy and (b) intellectual disability. In each subfigure, different clusters are shown in distinct colors; the highest scoring cluster is colored red. Diamond nodes indicate genes from the prior. Three levels of edge thickness denote increasing ranges of interaction likelihood scores. Solid versus dashed edges denote intra-cluster versus inter-cluster interactions, respectively

Our highest scoring cluster predicts another member of this family of genes, KCNQ5, which is widely expressed throughout the brain. The protein encoded by this gene yields currents that activate slowly with depolarization and can form heteromeric channels with the protein encoded by KCNQ3. It has recently been shown that KCNQ5 has a role in dampening synaptic inhibition in the hippocampus (Fidzinski et al., 2015). In particular, mice lacking functional KCNQ5 channels displayed increased excitability of different classes of neurons. Thus, KCNQ5 might be an interesting candidate for further analysis in the context of epilepsy.

The predicted cluster also suggests a role for the Calmodulin (CaM) proteins CALM1, CALM2, CALM3, which are calcium-binding messenger proteins with diverse roles in growth and cell cycle, signal transduction and synthesis and release of neurotransmitters. Recently, it has been shown by Ambrosino et al. (2015) that KCNQ2 BNFS-causing mutations express alterations in CaM binding and that in some cases CaM overexpression restored normal function of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3-induced channels. Our prediction thus supports these results by highlighting the importance of the interactions between KCNQ2 and the CaM proteins.

As a second biological case study, we applied our algorithm to predict protein complexes related to intellectual disability, a developmental disorder characterized by significant limitations in intellectual functioning and in practical, communicational and social skills. The corresponding DO term was associated with 234 prior genes. Our algorithm predicted 10 clusters, displayed in Figure 5(b). The top scoring cluster, which contains 17 proteins and 96 interactions, includes 11 members of the chromatin remodeling BAF complex (6 of them from the prior). This complex is responsible for DNA packaging and is thus regarded as a ‘program activation’ complex, making series of genes available for transcription. Mutations in chromatin regulators are widely associated with human mental disorders, such as intellectual disability, Coffin-Siris syndrome and Autism (Ronan et al., 2013). Another predicted chromatin regulator, CREBBP, is associated with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, whose phenotypes include moderate to severe learning difficulties.

Our top cluster also contains the KLF1 protein, which is known as a transcription regulator of erythrocyte development. Mutations of KLF1 are associated with dyserythropoietic anemia, a rare blood disorder characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis. Recently, Natiq et al. (2014) have reported on a patient with severe developmental delay, in which they observed chromosomal microdeletion containing (among others) the KLF1 gene. The exact impact of KLF1 on intellectual disability could thus be a subject for further analysis.

Finally, the EPAS1 gene is a hypoxia-inducible transcription factor activated at low oxygen levels. As hypoxia during birth is one of the reasons for intellectual disability, this prediction may highlight a different aspect of the disease and could be a candidate for further investigation.

4 Conclusions

We presented a network-based framework for discovering disease related protein complexes. We conducted several large-scale validations to show that the predicted clusters are densely interacting and significantly overlap known complexes and disease proteins. We also presented an expert analysis for two diseases, suggesting candidate proteins for further examination.

Currently, our approach does not take into account differences in the confidence of prior disease genes, nor other relevant information such as their association to diseases with similar phenotypes, expression patterns in the relevant tissues and mutation studies in model organisms. We believe that such data integration will allow predictions with higher coverage and accuracy.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science, Technology & Space of the State of Israel and the Helmholtz Centers, Germany. A.M. was supported in part by a fellowship from the Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics at Tel-Aviv University.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Amberger J. et al. (2009) McKusick’s Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Nucleic Acids Res., 37, D793–D796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino P. et al. (2015) Epilepsy-causing mutations in kv7. 2 c-terminus affect binding and functional modulation by calmodulin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1852, 1856–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Biervert C. et al. (1998) A potassium channel mutation in neonatal human epilepsy. Science, 279, 403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg Y. (2013) Chapter 15: disease gene prioritization. PLoS Comput. Biol., 9, e1002902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaldo P. et al. (2002) Benign familial neonatal convulsions caused by altered gating of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channels. J. Neurosci., 22, C199.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. (2014) Prioritizing protein complexes implicated in human diseases by network optimization. BMC Syst. Biol., 8, S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidzinski P. et al. (2015) KCNQ5 K+ channels control hippocampal synaptic inhibition and fast network oscillations. Nat. Commun., 6. doi:10.1038/ncomms7254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehndorf R. et al. (2011) PhenomeNET: a whole-phenome approach to disease gene discovery. Nucleic Acids Res., 39. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehndorf R. et al. (2015) Analysis of the human diseasome using phenotype similarity between common, genetic, and infectious diseases. Sci. Rep., 5.doi:10.1038/srep10888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoch C. et al. (2013) Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Nat. Genet., 45, 592–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S. et al. (2008) Walking the interactome for prioritization of candidate disease genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 82, 949–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage K. et al. (2007) A human phenome-interactome network of protein complexes implicated in genetic disorders. Nat. Biotechnol., 25, 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiserson M.D.M. et al. (2015) Pan-cancer network analysis identifies combinations of rare somatic mutations across pathways and protein complexes. Nat. Genet., 47, 106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magger O. et al. (2012) Enhancing the prioritization of disease-causing genes through tissue specific protein interaction networks. PLoS Comput. Biol., 8, e1002690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli F. et al. (2015) A novel KCNQ3 mutation in familial epilepsy with focal seizures and intellectual disability. Epilepsia, 56, e15–e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. et al. (2006) Challenges and strategies of the Genetics Home Reference. J. Med. Libr. Assoc., 94, 336–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natiq A. et al. (2014) A new case of de novo 19p13. 2p13. 12 deletion in a girl with overgrowth and severe developmental delay. Mol. Cytogenet., 7, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletscher-Frankild S. et al. (2014) DISEASES: Text mining and data integration of disease-gene associations. Methods, 74, 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P.N. et al. (2008) The Human Phenotype Ontology: a tool for annotating and analyzing human hereditary disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 83, 610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P.N. et al. (2014) Improved exome prioritization of disease genes through cross-species phenotype comparison. Genome Res., 24, 340–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronan J.L. et al. (2013) From neural development to cognition: unexpected roles for chromatin. Nat. Rev. Genet., 14, 347–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruepp A. et al. (2010) CORUM: the comprehensive resource of mammalian protein complexes–2009. Nucleic Acids Res., 38, D497–D501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santidrian A.F. et al. (2013) Mitochondrial complex I activity and NAD+/NADH balance regulate breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest., 123, 1068–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M.H. et al. (2012) HIPPIE: Integrating protein interaction networks with experiment based quality scores. PLoS One, 7, e31826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker A. et al. (2010) Improving disease gene prioritization using the semantic similarity of Gene Ontology terms. Bioinformatics, 26, i561–i567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriml L.M. et al. (2012) Disease Ontology: a backbone for disease semantic integration. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, D940–D946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons C. et al. (2015) Mutations in the voltage-gated potassium channel gene KCNH1 cause Temple-Baraitser syndrome and epilepsy. Nat. Genet., 47, 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.L. et al. (2005) The Mammalian Phenotype Ontology as a tool for annotating, analyzing and comparing phenotypic information. Genome Biol., 6, R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. (2000) Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet, 25, 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium (2014) Activities at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res., 42, D191–D198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanunu O. et al. (2010) Associating genes and protein complexes with disease via network propagation. PLoS Comput. Biol., 6, e1000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weckhuysen S. et al. (2012) KCNQ2 encephalopathy: emerging phenotype of a neonatal epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol., 71, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. et al. (2013) The network organization of cancer-associated protein complexes in human tissues. Sci. Rep., 3, 1583. doi:10.1038/srep01583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]