Abstract

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is an uncommon scarring hair loss disorder that is characterized by a band-like recession of the frontal hair line with eyebrow hair loss. We present a series of patients with FFA and increased sweating predominantly localized to the scalp, and potential explanations for this association are discussed. We hypothesize that the reported increase in sweating seen in our patients may be in part related to the inflammatory process occurring locally within the skin, either inducing a local axonal sweating reflex or through direct modulation of sweat gland secretion by neuropeptides.

Key Words: Alopecia, Inflammation, Sweating, Substance P, Calcitonin gene-related peptide

Established Facts

• Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is an uncommon inflammatory scarring hair loss disorder.

• It predominantly affects post-menopausal women, although there are growing reports of pre-menopausal women and men being affected.

Novel Insights

• Localized increased scalp sweating is observed in a group of women with FFA.

• Possible association between increased sweating and scalp inflammation is presented.

Introduction

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is an uncommon scarring hair loss disorder that is characterized by a band-like recession of the frontal hair line that is often associated with eyebrow, face and body hair loss [1]. The condition is permanent as the hair follicles (HFs) in the zones of alopecia are progressively destroyed and replaced by scar-like fibrous tissue [2]. FFA was first described by Kossard [2] in 1994, and since then, the incidence of the condition appears to be increasing [3,4,5,6,7].

We present a series of patients with FFA with associated increased sweating of the scalp and discuss potential explanations for this phenomenon.

Description of Cases

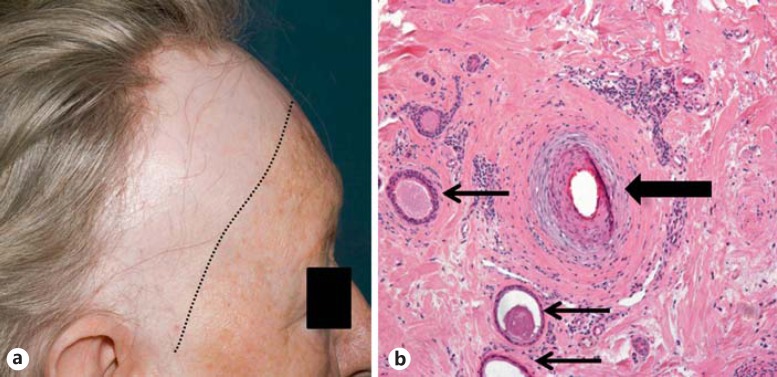

All patients were identified retrospectively from two specialist hair clinics (Manchester and Brighton). The diagnosis of FFA was confirmed by clinical evaluation (fig. 1a) and scalp biopsy. Each patient complained of increased sweating of the scalp, in some cases specifically localized to the area of alopecia. The sweating was sufficiently troublesome for patients to proffer the symptom without direct questioning. In 2 females, the sweating was of such severity that they would sleep on a towel each night to absorb excess sweat. In 1 case treated with localized botulinum toxin injections to the scalp, not only did sweating improve but reduction in itch and diminished visible inflammation was also observed. Clinical details for each patient are presented in table 1.

Fig. 1.

a Frontal hairline recession and loss of eyebrows. Close inspection reveals ‘band-like’ scarring alopecia with peri-follicular erythema and scale in the frontal hair margin (Patient 2). b Histopathology from the same patient reveals peri-follicular inflammation and fibrosis (thick arrow) with a dilated eccrine gland in close proximity to the affected HF (thin arrows).

Table 1.

Clinical summary of 11 patients with FFA and increased scalp sweating

| Patient | Diagnosis | Age, years | Sex | Menopause | PMH | Duration of hair loss | Clinical features | Sweating | Response to treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FFA (B) | 69 | F | Yes | Bilateral mastectomy for breast cancer; oesophagitis; hypothyroidism; amaurosis fugax | 7 years | Frontal recession with associated itching, burning and a stinging sensation of the scalp; perifollicular erythema and hyperkeratosis on examination | Increased sweating in distribution of hair loss; different to normal sweat – thick and smelly; wakes at night with a drenched pillow | Previous HCQ and pioglitazone = failed No treatment planned | |

| Histology showed one partly fibrosed follicle with follicular plugging, but no other features of lupus; localized lymph-histiocytic inflammatory infiltrate around the shaft of the remaining follicle and scarring in adjacent dermis consistent with FFA | ||||||||||

| 2 | FFA (B) | 75 | F | Yes | Hypercholesterolaemia; cerebral haematoma | 2 years | Frontotemporal hairline recession associated with itching of the scalp; symptoms were initially thought to be associated with statin therapy, but no change when stopping the treatment occurred | Severe sweating exactly over the area of hair loss; would leave scalp ‘dripping wet’; the sweating would occur anytime but was made worse by hot weather | Topical aluminium chloride (Driclor®) – some improvement in sweating Botulinum toxin injections (Botox®) = reduced sweating + itch within 2 weeks; also associated with reduced visible inflammation | |

| Alopecia screening bloods (including TFTs) = normal | Histology showed interface activity, loss of sebaceous glands and perifollicular fibrosis, in keeping with FFA; interestingly histology also demonstrated abnormally dilated eccrine glands/ducts (fig. 1b) | |||||||||

| 3 | FFA (B) | 67 | F | Yes | Systemic lupus erythematosus; bowel resection for ischaemic bowel secondary to diverticulosis Bloods – positive ANA; TFTs and glucose = normal | 6 years | Slowly progressive recession of the frontal hairline associated with itching and erythema of the scalp; associated with generalized hair thinning | Two-year history of ‘drenching sweats’ over the entire scalp, worse over the frontotemporal region | Treatment with HCQ for the lupus was poorly tolerated and therefore discontinued Intermittent topical corticosteroids Botulinum toxin injections declined | |

| 4 | FFA (M) | 70 | F | Yes | Asthma; eczema; rosacea | 3 years | Recession frontal of temporal hairline; perifollicular erythema; no symptoms | Increased scalp sweating | Topical corticosteroids – no progression | |

| 5 | FFA (M) | 62 | F | Menopause post-hysterectomy 20 years ago; HRT stopped due to s/e | Osteoporosis; OA; recurrent UTIs; low vitamin D; depression | 10 months | 3-year history of eyebrow loss; 10 months of frontal recession = progressive; scalp itch 2.5-cm recession from original hairline; perifollicular erythema; loss of eyebrows | Marked facial/scalp sweating | HCQ and doxycycline stopped due to s/e Gradual progression of hair loss | |

| 6 | FFA + FPHL (M) | 50 | F | Menopause 7 years ago | Joint pain; high cholesterol | 18 months | Progressive hairline recession; asymptomatic; loss of eyebrows | Sweating in hair-bearing margin | Topical minoxidil, topical corticosteroids and HCQ – stable at follow-up | |

| 4-cm recession from original hairline; low-grade perifollicular erythema | ||||||||||

| 7 | FFA (M) | 54 | F | Peri-menopausal hot flashes; increased scalp sweating | Sub-arachnoid haemorrhage 23 years ago; nephrotic syndrome; palindromic rheumatoid arthritis; spondylosis of neck; on HRT | 4–5 years | Always thin hair – progressive recession frontal hairline; occasional itch only; plucked eyebrows in past that never regrew 8-cm recession from original hairline; perifollicular erythema and scale | Scalp sweating | Progression despite lymecycline and HCQ | |

| 8 | FFA (M) | 64 | F | Menopause 20 years ago; HRT on and off – hysterectomy and ovary removal | Fatty liver, high BP, hay fever | 1 year | FFA and FPHL; recession = progressive; loss of eyebrows; asymptomatic 6.5-cm from original hairline; low-grade perifollicular erythema | Profuse facial and scalp sweating; no underlying cause identified Sweating worse with HCQ but improved with intralesional corticosteroids | Intralesional corticosteroids; topical corticosteroids Lymecycline improved sweating with intra-lesional steroid injections | |

| 9 | FFA (M) | 72 | F | Menopause at age 49; | Long-standing low WCC | 1 year | Shingles – followed by eyebrow loss 5 years ago – similar sensation this year, then hairline recession; still receding; occasional itch | Marked sweating from area of hair loss | Topical corticosteroids Hair loss stable at 1 year | |

| HRT from 3 months only – stopped | Loss of eyebrows; low-grade erythema; frontal recession mainly above the ears | |||||||||

| 10 | FFA (M) | 60 | F | Menopause at age 50 | High BP, hip pain | 4 years | Recession hairline – progressive; asymptomatic | Marked sweating from scalp; started after menopause; for the last 2 years only affected the scalp; has to sleep on a towel | Topical corticosteroids | |

| 6.5-cm recession from original hairline; perifollicular erythema; kinky hairs in frontal hairline | Trial of intralesional corticosteroids | |||||||||

| 11 | FFA (M) | 56 | F | Menopause 5 years ago | Depression (Note: treatment = citalopram) | 4 years | Eyebrow loss for 12 years; progressive hairline recession for 4 years | Marked sweating from scalp with minimal exertion/warmth; ‘drips off’ | Declined treatment | |

| Facial papules; low-grade perifollicular erythema; cutaneous LP on cheek | Sweats elsewhere on body but to a lesser degree; started after menopause | |||||||||

(B) = Brighton; (M) = Manchester; FPHL = female-pattern hair loss; ANA = anti-nuclear antibodies; TFTs = thyroid function tests; OA = osteoarthritis; UTIs = urinary tract infections; HRT = hormone replacement therapy; BP = blood pressure; s/e = side effects; WCC = white cell count; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; LP = lichen planus.

Discussion

Sweat is produced by eccrine sweat glands of which humans have several million distributed over nearly the entire body surface, with the palms, soles and scalp having the highest density. Each eccrine sweat gland consists of a secretory coil deep in the dermis and a duct that conveys the secreted sweat to the skin surface. Traditionally, the sweat gland is viewed as anatomically separate from the pilosebaceous unit; however, a recent morphological study suggests a much closer physical association with the HF, with the secretory coil consistently situated below the insertion of the arrector pili muscle close to the outer root sheath [8]. The primary function of the eccrine unit is thermoregulation, which is accomplished through the cooling effects of evaporation of sweat from the skin's surface. Sweating is a reflex function that is controlled through the sympathetic nervous system. Stimulation of eccrine sweat production is predominantly mediated through post-ganglionic production of acetylcholine, although locally generated neuropeptides, such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (cGRP), act to regulate sweat secretion rates [9].

Hyperhidrosis (or excessive sweating) can be classified in a number of ways including: (1) whether this process only affects sweating or occurs as part of a wider disease process (‘primary’ or ‘secondary’); (2) according to the distribution of sweating (‘generalized’ or ‘focal’), or (3) according to the source of neural impulse (‘cortical’, ‘hypothalamic’, ‘medullary’, ‘spinal cord’ or ‘local axon reflex’). For example, localized hyperhidrosis affecting the palms, soles and/or axillae (a presentation most familiar to dermatologists) would be classified as a primary, focal and cortical hyperhidrosis. A local axon reflex occurs when a stimulus applied to one branch of a nerve sets up an impulse that moves centrally to the point of division of the nerve where it is then reflected back down the other branch to the effector organ. It is a peripheral reflex that bypasses higher integration centres in the central nervous system. Blood vessels, sweat glands and mast cells are most important effectors of local axon reflexes affecting the skin.

FFA was first described by Kossard [2] in 1994 and is generally regarded as a variant of lichen planopilaris (LPP) based on similarity in lesion morphology and indistinguishable histological features [3,4]. A key event in the permanent HF loss seen in lesional FFA is the destruction of epithelial HF stem cells [2,10], likely due to a Th1-biased inflammatory response and loss of HF immune privilege [11]. However, it is still unclear what predisposes to this inflammatory attack; genetic susceptibility may be important, whereas environmental factors may explain the recent identification, pattern and growing incidence of the condition [12].

One hypothesis for the pathogenesis of scarring alopecias is neurogenic skin inflammation [2]. Evidence for this comes from animal models where stressed mice show increased expression of neuropeptides (including substance P), increased degranulation of mast cells, and loss of HF immune privilege [13,14,15,16,17]. Further, we know that in mice, nerve-derived hedgehog signaling maintains a subset of bulge stem cells expressing Gli1, suggesting a vital role of nerve signaling in supporting HF stem cell function [18]. In humans, total numbers of mast cells along with the proportion of degranulating mast cells are increased in the peri-follicular bulge region in LPP/FFA [19]. Early work examining nerve fibre density and expression of substance P and cGRP in FFA is currently limited to meeting proceedings (i.e. unpublished) but suggests variability in the expression of these neuropeptides between lesional and non-lesional scalp skin as well as differences between LPP and FFA disease groups [20]. In the clinic, many patients cite stress as a potential trigger for their hair loss [21].

Interestingly, many of these neurogenic skin inflammatory signals, particularly substance P and cGRP, are also important in sweat regulation [22]. We hypothesize that the reported increase in sweating seen in our patients may be in part related to the inflammatory process occurring locally within the skin, either inducing a local axonal sweating reflex or through direct modulation of sweat gland secretion by neuropeptide effects.

In 1 patient who responded to anti-sweating therapy in the form of botulinum toxin injections, improvements in scalp itch and visible inflammation were also observed. In a separate patient, the excess sweating improved with anti-inflammatory measures in the form of corticosteroid injections into the affected scalp skin. These observations highlight the potential interaction between (neurogenic) inflammation and sweating and suggest possible avenues for future therapy development (e.g. botulinum toxin injections, topical capsaicin, etc.). The role of neurogenic inflammation (and botulinum toxin therapy) has been proposed in a number of other inflammatory conditions, including psoriasis [23,24].

Another observation of note is the histological identification of dilated eccrine glands seen in 1 patient (fig. 1b). Eccrine gland changes are not well described in cicatricial alopecia, but it is likely that any change to these glands would represent a secondary phenomenon from either localized blockage of drainage (e.g. induced by localized fibrosis/inflammation) and/or gland atrophy (e.g. through inflammation-induced apoptosis/pressure effects). Interestingly, a number of reports describe the presence of syringomas in scalp biopsies for hair loss, including cases of cicatricial alopecia, although whether these are truly associated or just represent a coincidental finding requires further study (see Deen et al. [25] for a review of the literature).

Although the above arguments plausibly explain the apparent association between increased sweating and FFA, the following should also be considered: (1) coincidence: do these patients just have a localized primary hyperhidrosis or even just physiological levels of sweating, which has become more evident due to the loss of hair? Eyebrow loss in FFA means that sweat is no longer prevented from falling into the eyes, and wet hair exaggerates the appearance of the hair loss, with both features drawing attention to the sweating; or (2) menopause effects: all patients described here are post-menopausal women with a few also experiencing increased face and/or body sweating in addition. However, other menopausal symptoms were generally absent (except hot flashes in 1 patient), and many were already well past the peri-menopause period at the time when symptoms typically began [26]. Further, FFA is recognized to also affect face and body hair growth by the same process as on the scalp [7,27].

We present 11 women with FFA and associated scalp sweating. We propose that the mechanism for this may be through neurogenic inflammation and changes to localized neuropeptide signaling regulating sweating responses. Due to the retrospective nature of case identification and reliance on the patients providing information about their sweating unprompted, it is possible that increased sweating may in fact be more common than this report suggests (e.g. 8 of 116 FFA patients in the Manchester cohort) and should in future be specifically enquired about. Further work is required to confirm this potential association by objective quantification of hyperhidrosis and exploration of the underlying mechanisms, with particular focus on the role of neurogenic skin inflammation.

Statement of Ethics

As the study presents a retrospective case, no ethical approval is required.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Mark Taylor for the histological assessment of scalp biopsies. We also thank Dr. Enrique Poblet and Prof. Ralf Paus for their helpful comments about eccrine glands and the HF.

References

- 1.Harries MJ, Trueb RM, Tosti A, Messenger AG, Chaudhry I, Whiting DA, Sinclair R, Griffiths CE, Paus R. How not to get scar(r)ed: pointers to the correct diagnosis in patients with suspected primary cicatricial alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:482–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harries MJ, Paus R. The pathogenesis of primary cicatricial alopecias. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2152–2162. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955–961. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan KT, Messenger AG. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical presentations and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:75–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vano-Galvan S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcon C, Arias-Santiago S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Martorell-Calatayud A, Fernandez-Crehuet P, Grimalt R, Aranegui B, Grillo E, Diaz-Ley B, Salido R, Perez-Gala S, Serrano S, Moreno JC, Jaen P, Camacho FM. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poblet E, Jimenez-Acosta F, Hardman JA, Escario E, Paus R. Is the eccrine gland an integral, functionally important component of the human scalp pilosebaceous unit? Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:149–150. doi: 10.1111/exd.12889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumazawa K, Sobue G, Mitsuma T, Ogawa T. Modulatory effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P on human cholinergic sweat secretion. Clin Auton Res. 1994;4:319–322. doi: 10.1007/BF01821532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pozdnyakova O, Mahalingam M. Involvement of the bulge region in primary scarring alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:922–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harries MJ, Meyer K, Chaudhry I, E Kloepper J, Poblet E, Griffiths CE, Paus R. Lichen planopilaris is characterized by immune privilege collapse of the hair follicle's epithelial stem cell niche. J Pathol. 2013;231:236–247. doi: 10.1002/path.4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldoori N, Dobson K, Holden C, McDonagh AJ, Harries M, Messenger AG. Frontal fibrosing alopecia - possible association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens; a questionnaire study. Br J Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bjd.14535. accepted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters EM, Liotiri S, Bodo E, Hagen E, Biro T, Arck PC, Paus R. Probing the effects of stress mediators on the human hair follicle: substance P holds central position. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1872–1886. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters EM, Arck PC, Paus R. Hair growth inhibition by psychoemotional stress: a mouse model for neural mechanisms in hair growth control. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters EM, Handjiski B, Kuhlmei A, Hagen E, Bielas H, Braun A, Klapp BF, Paus R, Arck PC. Neurogenic inflammation in stress-induced termination of murine hair growth is promoted by nerve growth factor. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:259–271. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters EM, Kuhlmei A, Tobin DJ, Muller-Rover S, Klapp BF, Arck PC. Stress exposure modulates peptidergic innervation and degranulates mast cells in murine skin. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siebenhaar F, Magerl M, Peters EM, Hendrix S, Metz M, Maurer M. Mast cell-driven skin inflammation is impaired in the absence of sensory nerves. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:955–961. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brownell I, Guevara E, Bai CB, Loomis CA, Joyner AL. Nerve-derived sonic hedgehog defines a niche for hair follicle stem cells capable of becoming epidermal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:552–565. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harries M. The Immunopathobiology of lichen planopilaris; thesis. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hordinsky M, Doche I. Nerves and scarring alopecia disorders: a novel treatment approach. Cicatricial Alopecia Workshop - 23rd World Congress of Dermatology 2015. 2015 Vancouver, June. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang YZ, Bundy C, Griffiths CE, Paus R, Harries MJ. The role of beliefs: lessons from a pilot study on illness perception, psychological distress and quality of life in patients with primary cicatricial alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:130–137. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters EM, Ericson ME, Hosoi J, Seiffert K, Hordinsky MK, Ansel JC, Paus R, Scholzen TE. Neuropeptide control mechanisms in cutaneous biology: physiological and clinical significance. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1937–1947. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saraceno R, Kleyn CE, Terenghi G, Griffiths CE. The role of neuropeptides in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:876–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borodic GE, Acquadro M, Johnson EA. Botulinum toxin therapy for pain and inflammatory disorders: mechanisms and therapeutic effects. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:1531–1544. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.8.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deen K, Curchin C, Wu J. Incidental Syringomas of the scalp in a patient with scarring alopecia. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:171–177. doi: 10.1159/000437416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Archer DF, Sturdee DW, Baber R, de Villiers TJ, Pines A, Freedman RR, Gompel A, Hickey M, Hunter MS, Lobo RA, Lumsden MA, MacLennan AH, Maki P, Palacios S, Shah D, Villaseca P, Warren M. Menopausal hot flushes and night sweats: where are we now? Climacteric. 2011;14:515–528. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.608596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chew AL, Bashir SJ, Wain EM, Fenton DA, Stefanato CM. Expanding the spectrum of frontal fibrosing alopecia: a unifying concept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]