Abstract

Geobacter sulfurreducens RpoS sigma factor was shown to contribute to survival in stationary phase and upon oxygen exposure. Furthermore, a mutation in rpoS decreased the rate of reduction of insoluble Fe(III) but not of soluble forms of iron. This study suggests that RpoS plays a role in regulating metabolism of Geobacter under suboptimal conditions in subsurface environments.

The physiology of microorganisms in the family Geobacteraceae in the δ-Proteobacteria is of special interest, because these are commonly the predominant organisms in sedimentary environments in which Fe(III) reduction is important (1, 14, 31, 32, 35, 36). Their ability to oxidize aromatic contaminants with the reduction of Fe(III) (24, 25), reductively precipitate uranium (1, 26), or grow via reductive dehalogenation (6, 16) suggests that they can contribute to the bioremediation of a variety of contaminants in subsurface environments, such as aromatic hydrocarbons (2, 31, 32, 35) and uranium (1, 14).

The rpoS gene encodes a subunit of the RNA polymerase which is the master regulator of the general stress response in Escherichia coli and related bacteria (8, 9). This response is observed when cells face a number of different adverse or suboptimal growth conditions and is commonly accompanied by a reduced growth rate or entry into stationary phase. Thus, in the Geobacteraceae RpoS might be expected to play a role in metabolic adaptation during growth in the subsurface, where it is expected to be more analogous to the stationary phase of culture than to the exponential phase. The goal of the present work was to initiate the study of the role of RpoS in Geobacter sulfurreducens in an attempt to understand the mechanisms of stress responses in the Geobacteraceae. G. sulfurreducens serves as a model because it is closely related to the Geobacter species that predominate in subsurface environments, it can be cultured in laboratory conditions, and its genome sequence (28) as well as a genetic system is available (5).

G. sulfurreducens genome contains an rpoS homologue gene.

A search of the G. sulfurreducens genome sequence (www.tigr.org), using the E. coli rpoS gene as a query, revealed an open reading frame encoding a protein which has 42% identity with the RpoS protein of E. coli and consists of 328 amino acids with a molecular mass of 38 kDa. It has 87 and 68% amino acid identity with putative RpoS proteins of Geobacter metallireducens and Desulfuromonas acetoxidans, two other members of the Geobacteraceae (preliminary genome sequence data are available at http://www.jgi.doe.gov).

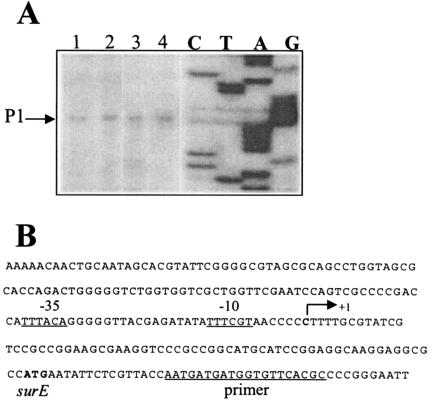

The genetic arrangement of the G. sulfurreducens rpoS region differs from that of E. coli and related bacteria. The nlpD gene, encoding an outer membrane lipoprotein (17), is absent, but this region contains a gene, downstream of rpoS, whose deduced amino acid sequence has 47.5% identity to the adenine phosphoribosyltransferase enzyme Apt of E. coli, which is involved in the one-step salvage pathway of adenine to AMP (12). Reverse transcription-PCR analysis demonstrated that rpoS forms part of the operon surE-pcm-rpoS-apt (data not shown). However, the presence of additional rpoS-containing transcripts cannot be discounted. Primer extension analyses of the surE-pcm-rpoS-apt operon were carried out, as described previously (3), with total RNA extracted from the wild-type strain DL1 (4) and rpoS mutant DLCN16(ΔrpoS::Km) grown in NBAF media (5) and with oligonucleotide surEPE (5′-GCGTGAACACCATCATC-3′) (which is complementary to the 5′ region of the surE gene). As shown in Fig. 1, the surE promoter contains −10 (TTTCGT) and −35 (TTTACA) sequences which are similar to the consensus sequences recognized by E. coli σ70. This promoter was found to be RpoS independent either in the logarithmic or in the stationary phase of growth (Fig. 1). This is similar to E. coli, in which the transcription of surE, pcm, and rpoS is RpoS independent (10, 20). The rpoS mutant DLCN16(ΔrpoS::Km) was constructed as described previously (18), using the oligonucleotides rpoS1 (5′-CTTACATGGTCGCCCTGATG-3′) and rpoS2 (5′-CATGGAGATCTCCGTCGC-3′) to amplify the upstream region of rpoS, oligonucleotides rpoS5 (5′-CGAGGCCAAGTCTCTGG-3′) and rpoS6 (5′-GCCGTATTCGAGCTGATAGG-3′) to amplify the rpoS downstream region, and oligonucleotides rpoS3 (5′-GCGACGGAGATCTCCATGACCTGGGATGAATGTCAGCTAC-3′) and rpoS4 (5′-CCAGAGACTTGGCCTCGAGAAGGCGGCGGTGGAATCG-3′) to amplify the kanamycin cassette. This cassette was inserted in the same orientation as that of rpoS transcription, resulting in a nonpolar mutation. This was confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR analysis using total RNA extracted from DLCN16 cultures and oligonucleotides designed to amplify the apt gene (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Primer extension analysis of surE in G. sulfurreducens DL1 (lanes 1 and 3) and rpoS mutant DLCN16 (lanes 2 and 4). Total RNA was extracted from mid-log (lanes 1 and 2) or stationary-phase (lanes 3 and 4) cultures. The transcription initiation site P1 is indicated. (B) DNA sequence of the surE regulatory region. The arrow indicates the transcription start point.

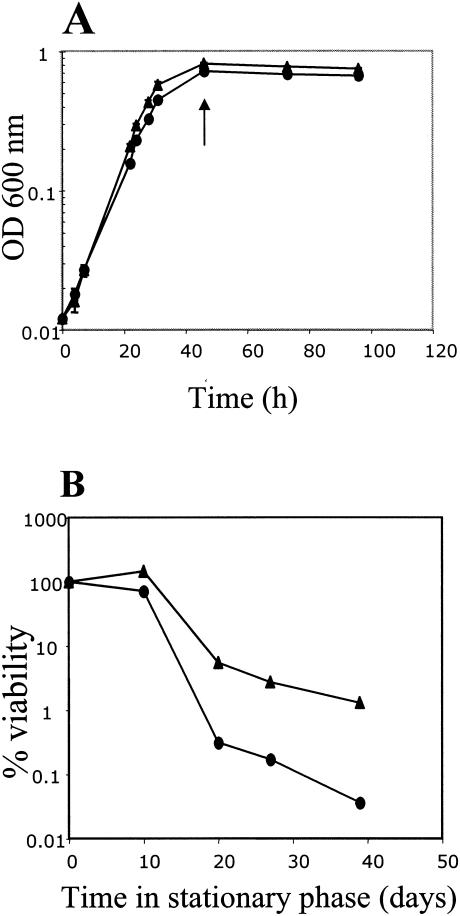

Stationary-phase survival in the rpoS mutant, using NBAF medium with limiting acetate (8 mM) as electron donor and excess fumarate (37 mM) as electron acceptor (5), decreased at least 10-fold compared to that of the wild-type strain DL1, indicating that RpoS is involved in stationary-phase survival of G. sulfurreducens (Fig. 2). This result is consistent with the fact that G. sulfurreducens rpoS is cotranscribed with surE, pcm, and apt, whose products are necessary for stationary-phase survival in E. coli (7, 19, 38).

FIG. 2.

(A) Growth of G. sulfurreducens DL1 (triangles) and rpoS mutant (circles) in media containing acetate as the electron donor and fumarate as the electron acceptor. Data are means of triplicates. The arrow indicates time zero of the survival curve. OD 600, optical density at 60 nm. (B) Stationary-phase survival of DL1 (triangles) and rpoS mutant DLCN16 (circles). Percent viability is expressed as the viable cell number at each time point divided by the viable cell number at time zero. Similar results were obtained in three experiments.

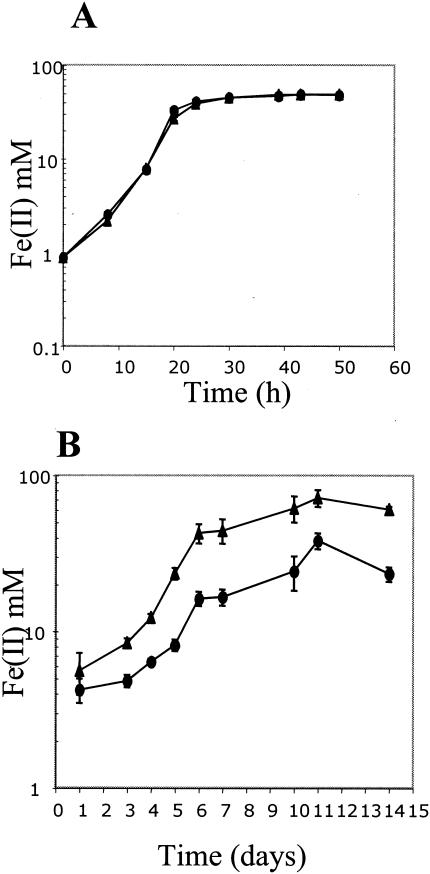

The utilization of either fumarate or soluble Fe(III) [in the form of Fe(III) citrate] as electron acceptor was not affected in the rpoS mutant (Fig. 2A and 3A); in contrast, the reduction of insoluble Fe(III) (Fig. 3B) was significantly diminished in the rpoS mutant compared to that of the wild-type strain. The same result was obtained with two independent rpoS mutant isolates. This result suggests that RpoS may regulate the expression of genes in G. sulfurreducens that are specifically required for the reduction of insoluble Fe(III) oxide, the primary form of Fe(III) in most sedimentary environments. Preliminary studies have indicated that the pattern of c-type cytochromes in the rpoS mutant is different from that in the wild-type strain (data not shown), which is significant because c-type cytochromes are involved in electron transfer to Fe(III) in G. sulfurreducens (18, 22, 27). The identity of such c-type cytochromes is presently being investigated.

FIG. 3.

Fe(III) citrate (A) or poorly crystalline Fe(III) oxide (B) reduction in the wild-type strain DL1 (triangles) and rpoS mutant (circles) in media containing acetate as electron donor. Determination of Fe(II) was carried out as previously described (30). Data are means of triplicates.

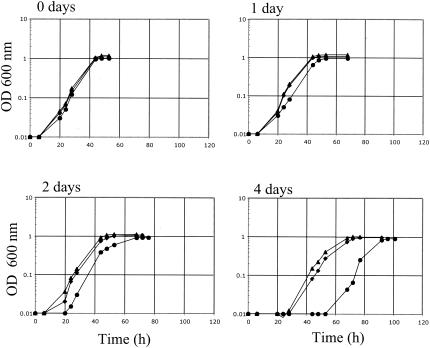

Although G. sulfurreducens was originally designated a strict anaerobe (4), subsequent studies demonstrated that it can tolerate long-term exposure to oxygen (21). Oxygen intrusions into sediments in which Geobacter species predominate are common, and thus the ability to tolerate oxygen exposure is an important feature in the survival of these organisms (21). As shown in Fig. 4, tolerance to oxygen was clearly reduced in the rpoS mutant DLCN46(ΔrpoS::Cm) after 4 days of exposure and it was rescued in the rpoS-complemented mutant strain DLCN52(ΔrpoS::Cm/rpoS+). (The procedure for the construction of a ΔrpoS::Cm mutant was the same as that for the DLCN16 mutant, except that oligonucleotides rpoSCm-3 [5′-GCGACGGAGATCTCCATGACGGAAGATCACTTCGC-3′] and rpoSCm4 [5′-CCAGAGACTTGGCCTCGAGGGCAGCAATAACTGCC-3′] were used to amplify the chloramphenicol cassette; the complementation was achieved, as described before [29], by cointegration of plasmid pCNDL17, a PCR 2.1-TOPO derivative [Kmr] [Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.] carrying the entire rpoS gene.) These results indicate that RpoS is involved in the aerotolerance of G. sulfurreducens, which is consistent with its role in oxidative-stress resistance in other bacteria (15, 34, 37). However, the fact that the rpoS mutant of G. sulfurreducens was still viable after 4 days of oxygen exposure indicates that the mechanism for coping with oxidative damage is only partially RpoS dependent.

FIG. 4.

Aerotolerance of DL1 (wild type) (triangles), DLCN46(rpoS::Cm) (circles), and DLCN52(rpoS::Cm/rpoS+) (diamonds) after 0, 1, 2, and 4 days of air exposure. Data are means of triplicates. Survival was estimated as the lag time of growth of a culture derived from oxygen-exposed cells as described previously (21); determination of CFU was not feasible due to the fact that G. sulfurreducens forms cellular aggregates when exposed to oxygen, a trait that was enhanced by the rpoS mutation. OD 600, optical density at 600 nm.

G. sulfurreducens RpoS had no apparent function in resistance to high temperature (45°C for 7 days) or alkaline pH (pH 6 for 60 min) (data not shown), indicating that some stress response mechanisms are not controlled by RpoS. In addition to RpoS and the well-known sigma factors RpoD (σ70), RpoH (σ32), RpoF (σ28), and RpoN (σ54), G. sulfurreducens contains a sigma factor that belongs to the family having extracytoplasmic functions (data not shown) (23). This sigma factor, designated RpoE, is likely to be involved in resistance to oxidative stress and other adverse conditions in G. sulfurreducens based on its role in E. coli and other gram-negative bacteria (11, 13, 33); however, this remains to be investigated.

This first study of RpoS in a member of the δ-Proteobacteria illustrates some similarities and differences in gene organization and function compared to those of other classes of previously investigated Proteobacteria. The effect of the rpoS mutant on survival in stationary phase and on reduction of Fe(III) oxide, the primary electron acceptor supporting the growth of Geobacteraceae, suggests that RpoS may play a role in controlling activity of G. sulfurreducens in subsurface environments. Thus, it seems likely that further investigation of the RpoS regulon will provide insights into the mechanisms by which G. sulfurreducens and related organisms function so effectively in Fe(III)-reducing subsurface environments.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Genomes to Life program, U.S. Department of Energy (grant DE-FC02-02ER63446). C.N. was the recipient of a DGAPA/UNAM Postdoctoral Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, R. T., H. A. Vrionis, I. Ortiz-Bernad, C. T. Resch, P. E. Long, R. Dayvault, K. Karp, S. Marutzky, D. R. Metzler, A. Peacock, D. C. White, M. Lowe, and D. R. Lovley. 2003. Stimulating the in situ activity of Geobacter species to remove uranium from the groundwater of a uranium-contaminated aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5884-5891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, R. T., and D. R. Lovley. 1999. Naphthalene and benzene degradation under Fe(III)-reducing conditions in petroleum-contaminated aquifers. Bioremediation J. 3:121-135. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrios, H., H.-M. Fischer, H. Hennecke, and E. Morett. 1995. Overlapping promoters for two different RNA polymerase holoenzymes control Bradyrhizobium japonicum nifA expression. J. Bacteriol. 177:1760-1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caccavo, F., Jr., D. J. Lonergan, D. R. Lovley, M. Davis, J. F. Stolz, and M. J. McInerney. 1994. Geobacter sulfurreducens sp. nov., a hydrogen- and acetate-oxidizing dissimilatory metal-reducing microorganism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3752-3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coppi, M. V., C. Leang, S. J. Sandler, and D. R. Lovley. 2001. Development of a genetic system for Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3180-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Wever, H., J. R. Cole, M. R. Fettig, D. A. Hogan, and J. M. Tiedje. 2000. Reductive dehalogenation of trichloroacetic acid by Trichlorobacter thiogenes gen. nov., sp. nov. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2297-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs, G. 1999. Biosynthesis of building blocks, p. 111-157. In J. W. Lengeler, G. Drews, and H. G. Schlegel (ed.), Biology of the prokaryotes. Blackwell Scientific, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Hengge-Aronis, R. 1996. Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase, p. 1497-1512. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2000. The general stress response in Escherichia coli, p. 161-178. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the σS (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:373-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershberger, C. D., R. W. Ye, M. R. Parsek, Z. D. Xie, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1995. The algT (algU) gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a key regulator involved in alginate biosynthesis, encodes an alternative sigma factor (sigma E). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7941-7945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hershey, H. V., and M. W. Taylor. 1986. Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of Escherichia coli adenine phosphoribosyltransferase and comparison with other analogous enzymes. Gene. 43:287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiratsu, K., M. Amemura, H. Nashimoto, H. Shinagawa, and K. Makino. 1995. The rpoE gene of Escherichia coli, which encodes σE, is essential for bacterial growth at high temperature. J. Bacteriol. 177:2918-2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes, D. E., K. T. Finneran, R. A. O'Neil, and D. R. Lovley. 2002. Enrichment of members of the family Geobacteraceae associated with stimulation of dissimilatory metal reduction in uranium-contaminated aquifer sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2300-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivanova, A., C. Miller, G. Glinsky, and A. Eisenstark. 1994. Role of rpoS (katF) in oxyR-independent regulation of hydroperoxydase I in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 12:571-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krumholz, L. R. 1997. Desulfuromonas chloroethenica sp. nov. uses tetrachloroethylene and trichloroethylene as electron acceptors. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:1262-1263. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange, R., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1994. The nlpD gene is located in an operon with rpoS on the E. coli chromosome and encodes a novel lipoprotein with a potential function in cell wall formation. Mol. Microbiol. 13:733-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leang, C., M. V. Coppi, and D. R. Lovley. 2003. OmcB, a c-type polyheme cytochrome, involved in Fe(III) reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. J. Bacteriol. 185:2096-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, C., and S. Clarke. 1992. A protein methyltransferase specific for altered aspartyl residues is important in Escherichia coli stationary-phase survival and heat shock resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9885-9889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, C., P. Y. Wu, and M. Hsieh. 1997. Growth-phase-dependent transcriptional regulation of the pcm and surE genes required for stationary-phase survival of Escherichia coli. Microbiology 143:3513-3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin, W. C., M. V. Coppi, and D. R. Lovley. 2004. Geobacter sulfurreducens can grow with oxygen as terminal electron acceptor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2525-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lloyd, J. R., C. Leang, A. L. Hodges Myerson, M. V. Coppi, S. Cuifo, B. Methe, S. J. Sandler, and D. R. Lovley. 2003. Biochemical and genetic characterization of PpcA, a periplasmic c-type cytochrome in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biochem. J. 369:153-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lonetto, M. A., K. L. Brown, K. E. Rudd, and M. J. Buttner. 1994. Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase sigma factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7573-7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovley, D. R., M. J. Baedecker, D. J. Lonergan, I. M. Cozzarelli, E. J. Phillips, and D. L. Siegel. 1989. Oxidation of aromatic contaminants coupled to microbial iron reduction. Nature 339:297-299. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovley, D. R., and D. J. Lonergan. 1990. Anaerobic oxidation of toluene, phenol, and p-cresol by the dissimilatory iron-reducing organism, GS-15. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1858-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovley, D. R., E. J. P. Phillips, Y. A. Gorby, and E. R. Landa. 1991. Microbial reduction of uranium. Nature 350:413-416. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnuson, T. S., N. Isoyama, A. L. Hodges-Myerson, G. Davidson, M. J. Maroney, G. G. Geesey, and D. R. Lovley. 2001. Isolation, characterization and gene sequence analysis of a membrane-associated 89 kDa Fe(III) reducing cytochrome c from Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biochem. J. 359:147-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Methe, B. A., K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, I. T. Paulsen, W. Nelson, J. F. Heidelberg, D. Wu, M. Wu, N. Ward, M. J. Beanan, R. J. Dodson, R. Madupu, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, S. A. Sullivan, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, T. M. Davidsen, N. Zafar, O. White, B. Tran, C. Romero, H. A. Forberger, J. Weidman, H. Khouri, T. V. Feldblyum, T. R. Utterback, S. E. Van Aken, D. R. Lovley, and C. M. Fraser. 2003. Genome of Geobacter sulfurreducens: metal reduction in subsurface environments. Science 302:1967-1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Núñez, C., S. Moreno, G. Soberón-Chávez, and G. Espín. 1999. The Azotobacter vinelandii response regulator AlgR is essential for encystment. J. Bacteriol. 181:141-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillip, E. J. P., and D. R. Lovley. 1987. Determination of Fe(III) and Fe(II) in oxalate extracts of sediments. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 51:938-941. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roling, W. F., B. M. van Breukelen, M. Braster, B. Lin, and H. W. van Verseveld. 2001. Relationship between microbial community structure and hydrochemistry in a landfill leachate-polluted aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4619-4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rooney-Varga, J. N., R. T. Anderson, J. L. Fraga, D. Ringelberg, and D. R. Lovley. 1999. Microbial communities associated with anaerobic benzene degradation in a petroleum-contaminated aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3056-3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouviere, P. E., A. De Las Penas, J. Mecsas, C. Z. Lu, K. E. Rudd, and C. A. Gross. 1995. rpoE, the gene encoding the second heat-shock sigma factor, sigma E, in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 14:1032-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sak, B. D., A. Eisenstark, and D. Touati. 1989. Exonuclease III and catalase hydroperoxydase II in Escherichia coli are both regulated by the katF product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3271-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snoeyenbos-West, O. L., K. P. Nevin, R. T. Anderson, and D. R. Lovley. 2000. Enrichment of Geobacter species in response to stimulation of Fe(III) reduction in sandy aquifer sediments. Microb. Ecol. 39:153-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein, L. Y., M. T. La Duc, T. J. Grundl, and K. H. Nealson. 2001. Bacterial and archaeal populations associated with freshwater ferromanganous micronodules and sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 3:10-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strohmeier-Gort, A., D. M. Ferber, and J. A. Imlay. 1999. The regulation and role of the periplasmic copper, zinc superoxide dismutase of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 32:179-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visick, J. E., J. K. Ichikawa, and S. Clarke. 1998. Mutations in the Escherichia coli surE gene increase isoaspartyl accumulation in a strain lacking the pcm repair methyltransferase but suppress stress-survival phenotypes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 167:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]