Abstract

Background:

Stress can alter response to nociception. Under certain circumstances stress enhances nociception, a phenomenon which is called stress-induced hyperalgesia (SIH). While nociception has been studied in this paradigm, possible alterations occurring in passive avoidance (PA) learning after exposing rats to this type of stress has not been studied before.

Materials and Methods:

In the current study, we evaluated the effect of chronic swim stress (FS) or sham swim (SS) on nociception in both spinal (tail-flick) and supraspinal (53.5°C hot-pate) levels. Furthermore, PA task was performed to see whether chronic swim stress changes PA learning or not. Mobility of rats and anxiety-like behavior were assessed using open-field test (OFT).

Results:

Supraspinal pain response was altered by swim stress (hot-plate test). PA learning was impaired by swim stress, rats in SS group did not show such impairments. Rats in the FS group showed increased mobility (rearing, velocity, total distant moved (TDM) and decreased anxiety-like behavior (time spent in center and grooming) compared to SS rats.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated the simultaneous impairment of PA and nociception under chronic swim stress, whether this is simply a co-occurrence or not is of special interest. This finding may implicate a possible role for limbic structures, though this hypothesis should be studied by experimental lesions in different areas of rat brain to assess their possible role in the pathophysiology of SIH.

Keywords: Nociception, passive avoidance learning, stress-induced hyperalgesia, swim stress

INTRODUCTION

Acute stress leads to analgesia (stress-induced analgesia: SIA),[1] while under certain circumstances stress exacerbates pain, a situation which is called stress-induced hyperalgesia (SIH). Although SIA physiology is extensively studied, many aspects of SIH are yet unclear and different transmitters are suggested to be involved in its physiology.[2,3] Imaging studies have revealed a critical role for amygdala in the processing of pain and cognitive functions like learning and memory in chronic pain patients.[4] It is previously shown that stressors can alter amygdala-dependent fear conditioning and passive avoidance (PA) learning and interestingly, different stressors have different effect on PA learning.[5,6,7,8,9]

A number of animal models for long-lasting SIH have been developed.[10,11,12,13] Quintero et al. introduced sub chronic swim stress as a model for long-lasting hyperalgesia.[11] They introduced a 3-day swimming stress protocol to induce SIH in the rats.

While nociception has been studied in this paradigm, possible alterations occurring in PA learning after exposing rats to this type of stress has not been studied before. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of chronic swim stress on PA learning along with nociception in two separate groups undergoing sub-chronic swim stress to see the possible effect of chronic swim stress on PA learning.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All the procedures were performed in accordance with the regulations set by Kerman university of medical sciences ethics committee regarding experiments on vertebrate animals [ethics committee code: EC/KNRC/92-7]. Maximum effort was made throughout the experiments to minimize discomfort for the animals. Adult male Sprague dawley rats (180-250 gr) were used in this study. Animals were housed individually in a room with controlled temperature with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water. All the procedures were performed between 7:00 AM and 16:00 PM by two experienced persons. Four experimental groups (each consisting at least 8 rats) were used in this study: 1- forced swim (FS), nociception (hot-plate, tail flick, OFT tests were) 2- FS, PA task (PA task, open field Test (OFT)) 3- sham swim (SS), nociception 4- SS, PA task. Baseline measurements were made for rats in the nociception group at day 0. After stressing the rats for 3 days, post-stress tests were performed on days 4 and 5 of the protocol. Furthermore, nociception was measured on days 8 and 12 to test the prolonged alterations observed in previous studies.

Rats were brought to the laboratory 1 hour before applying stress to them. FS group were subjected to swim stress by placing in a plastic cylinder (30 cm diameter, height 50 cm) for 10 minutes in 24-26°C water on day 1. On days 2 and 3, the same swim stress was given to the animals for 20 minutes. Control rats were subjected to sham swim by placing them in a cylinder containing only 2-4 cm of water.[11] Rats were allowed to dry in a cool environment and efforts were made to minimize handling of the animals to avoid possible novelty stresses which might affect the results. After 3 consecutive days of swim stress or sham swim, we evaluated the PA task on the days 4 and 5, and measure the nociceptive responsiveness on the day 4. Open-field test was used to evaluate the mobility and anxiety of rats. It was performed on the day 4 at least 2 hours before the other procedures.

Twenty-four hours after the last swimming session, animals were brought to the testing environment and after a 1 h acclimation period, animals were placed in the middle of open field and the horizontal and vertical activities of the rats were recorded for a period of 5 min and then analyzed using Ethovision software [version 7.1], a video tracking system for automation of behavioral experiments [Noldus Information Technology, the Netherlands]. The apparatus consisted of a square arena [56 × 56 × 20 [H] cm] made of black wood and its floor was divided by lines into 16 squares dividing the field into central and peripheral squares. The following behavioral parameters were recorded for each rat: Total distance moved [TDM, cm], time spent in center and periphery and frequency of grooming and rearing [as a measure of vertical activity]. At the end of each session, rats were removed from the open field and the experimental chamber was cleaned with a damp cloth and dried.[14,15]

Hot plate test was used to measure reaction time to the thermal stimuli.[16] In this procedure, pain sensitivity was evaluated by using a device (LE710 model, Lsi LETICA, Spain) that contained a plate with the diameter of 19 cm and a Plexiglas wall with height of 30 cm. Plate temperature was adjusted to 52 ± 2°C. Reaction time to thermal pain was considered as the time between onset of test and the beginning of nociceptive response including whether licking front paw or jumping (cut-off time was considered 45 sec to avoid tissue damage).[14,17]

We used this method to assess the nociceptive response to acute pain stimuli in spinal level. This measure was used due to the fact that response to heat noxious stimuli to the tail of the animal is a reflex,[16] and we evaluated to see whether reflex movements is affected by swim stress or not. Animals were restrained in a restrainer cage with their tail hanging free and allowed to adapt for 30 min before testing. The lower 5 cm portion of the tail was marked. This part of the tail was put under the burning light and the response time to the stimuli was considered as the time between turning the burning light on and tail drawn out.

PA learning was assessed using inhibitory PA paradigm. A shuttle-box device with dimensions of 100×25×25 which consisted two parts was used. First, animals were placed in light arena of shuttle-box apparatus then the door was opened and the animal was allowed to go to the dark sector, then the door was closed without electric shock and the animal was placed in the cage. 30 minutes later, this step was repeated again and the third time that the animal entered dark sector, an electric shock was administered to the animal (0.5 A, 5 ms) then the animal was returned to the cage. Twenty-four hours after training, the test was performed to evaluate memory and learning; in this step animal was placed in light arena of shuttle-box apparatus. After 30 seconds, the door opened and the time required to enter the dark sector was recorded as retention time (step-through latency (STL)). Total dark complement (TDC) and number of entrance into dark sector were recorded as indicator of contextual learning.[18,19]

Student t-test and paired t-test were used to compare the nociceptive response and PA learning compared to the other group or in comparison to baseline measurements. Data were analyzed using SPSS V.16 (SPSS Inc., USA) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

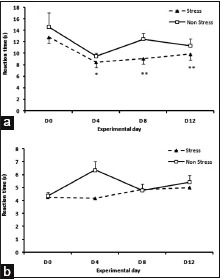

Thermal pain threshold was significantly decreased in the FS (nociception) group (nociception) in the hot-plate test on days 4, 8 and 12 compared to baseline (paired t-test, P < 0.01) while no difference between post stress and pre-stress was observed in SS (nociception) rats. No significant change compared to baseline was observed in response threshold to thermal stimuli in the tail-flick test in both FS and SS (nociception) rats (P > 0.05) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Decreased pain threshold compared to baseline in hot-plate test following 3 days of swimming stress on days 4, 8 and 12. No significant changes were observed in the sham swim group as compared to baseline. (b) No significant change in tail-flick latency was observed in forced swim or sham swim rats compared to baseline. (Paired t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to baseline, n = 8 for each group, data presented as Mean ± S.E.M)

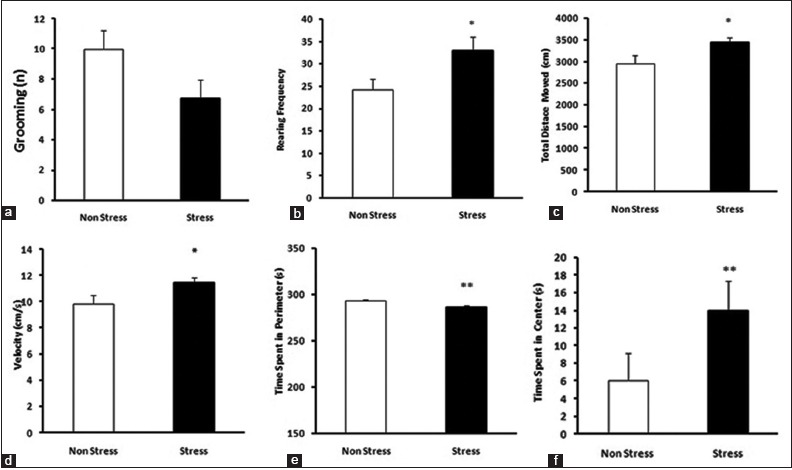

An increased locomotion was observed in the FS rats (nociception) in the open field test compared to SS (nociception). Rearing, total distance moved (TDM) and velocity were increased in the FS (nociception) group compared to SS (nociception) (t-test, P < 0.05). Time spent in perimeter was significantly different between SS (nociception) and FS (nociception) group (t-test, P < 0.05); rats in the SS (nociception) group stayed more in the perimeter in comparison to FS (nociception) rats, which is a routine response to the novel stress of environment, while FS (nociception) group did stay more in the center of the open field compared to SS (nociception) rats, indicating a prior exposure to stress [20] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

(a) Grooming was not different between forced swim (FS) and sham swim (SS) group rats. (b-d) Increased locomotion observed in FS rats compared to SS. (e) Rats in the SS group stayed more in periphery, showing normal behavior in open-field test (OFT). (f) Rats of the FS group stayed more in center of the field, showing previous exposure to stress. (t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with each other, n = 8 for each group, data presented as Mean ± S.E.M)

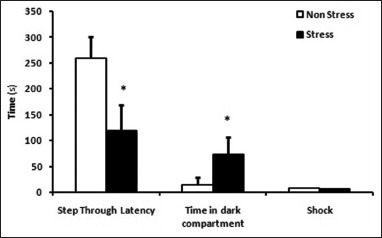

Rats in the FS (PA task) group showed retention impairment in PA task [Figure 3]; a significant reduction in STL was observed in these rats compared to the SS (PA task) group (t-test, P < 0.01). Number of shocks received on day 4 was significantly increased in the FS (PA task) group compared to SS (PA task) (t-test, P < 0.05). TDC was also increased in the FS (PA task) group compared to SS (PA task), showing impairments in contextual memory (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Decreased step through latency (STL) was observed in the FS group rat compared to the SS group. Increased time spent in dark sector and entrance number into dark section observed in FS rats compared to SS rats on day 5 (retrieval session). (Student t-test, *P < 0.05, n = 8 for each group, data presented as Mean ± S.E.M)

DISCUSSION

In this study, chronic swimming stress induced thermal hyperalgesia at the supraspinal level in the hot plate test, while no changes were observed in tail-flick test, a finding which Quintero et al. (2000) did not report in their study.[11] This finding suggests a CNS alteration to pain stimuli processing rather than a peripheral one and further research would clarify the exact mechanisms involved.

Consistent with this hypothesis, Spuz et al. (2012) showed that inactivation of NMDA receptors by AP5 or CNQX in CeA suppresses the affective aspects of pain, while the spinal motor reflex remains unaffected.[21]

PA learning was impaired in FS rats compared to the rats subjected to SS. It is previously shown that opioid receptors of basolateral amygdala (BLA) have an important role in the PA impairments following swim stress and it seems that endogenous opioids released following swim stress play an important role in the modulation of memory formation in PA task.[22,23]

Limbic changes after exposure to chronic stress has been shown before. Jovanovic et al. (2011) showed a disconnection between amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex in the subjects undergoing chronic social stress by using PET scan. Their subjects also showed impairment in hippocampus-dependent tasks. Impairment of the PA task in our study is an indirect indicator of amygdala and hippocampus dysfunction as demonstrated by previous studies.[22,24] Further research using experimental lesional studies in different areas of amygdala and hippocampus during swim stress paradigm would clarify the exact role of these nuclei in the pathogenesis of SIH and would clearly state that whether the simultaneous impairment of PA task and nociception is a co-occurrence with different mechanisms or a similar mechanism contributes to the pathogenesis of both impairments.

Locomotion was increased in rats undergoing swim stress compared to sham swim group. Consistent with this finding, Zhang et al. (2011) showed simultaneous antinociception and excessive grooming following acute restraint stress in per-1 mutant mice.[25] We have also observed excessive rearing in the FS group, although we cannot explain this finding, but one possible reason might be due to changes in glutamate/GABA balance which is observed in the SIH model.[26] Movement centers of the brain, like basal ganglia, are directly controlled by glutamate/GABA neurotransmitters [27] and one possible explanation for increased mobility and grooming might be the increased stimulation of motor cortex due to decreased inhibition of basal ganglia although this is just a hypothesis which might be precisely tested in further studies.

Rats in the FS group stayed in center more than the SS group (which shows previous exposure to stress)[20] implicating a decreased level of anxiety. While this seems irrational, impact of previous exposure to stress may explain this finding.[27]

Role of nitric oxide [28] and other neurotransmitters [29] in the association of memory and nociception impairments has been reported before. Though we have not examined these mechanisms, but we suggest further studies to evaluate the neurobiological basis of pain and memory disruption association.

CONCLUSION

We have shown the association of thermal hyperalgesia, PA task impairment and increased locomotion following chronic swim stress. We suggest further studies targeting different areas of amygdala and hippocampus using neurotoxic agents to examine the exact role of these nuclei in the initiation and maintenance of SIH. Although we observed an association, further research should be conducted to see whether a common pathway is indicated for this association or it's just a co-occurrence involving two different neural pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was accomplished using grant from Kerman Neuroscience Research Center [grant no: KNRC/92-7].

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carrive P, Churyukanov M, Le Bars D. A reassessment of stress-induced “analgesia” in the rat using an unbiased method. Pain. 2011;152:676–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres IL, Vasconcellos AP, Silveira Cucco SN, Dalmaz C. Effect of repeated stress on novelty-induced antinociception in rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:241–4. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashiguchi H, Ye SH, Morris M, Alexander N. Single and repeated environmental stress: Effect on plasma oxytocin, corticosterone, catecholamines, and behavior. Physiol Behav. 1999;61:731–6. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jovanovic H, Perski A, Berglund H, Savic I. Chronic stress is linked to 5-HT (1A) receptor changes and functional disintegration of the limbic networks. Neuroimage. 2011;55:1178–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baran SE, Armstrong CE, Niren DC, Hanna JJ, Conrad CD. Chronic stress and sex differences on the recall of fear conditioning and extinction. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91:323–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baratta MV, Christianson JP, Gomez DM, Zarza CM, Amat J, Masini CV, et al. Controllable versus uncontrollable stressors bi-directionally modulate conditioned but not innate fear. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henningsen K, Andreasen JT, Bouzinova EV, Jayatissa MN, Jensen MS, Redrobe JP, et al. Cognitive deficits in the rat chronic mild stress model for depression: Relation to anhedonic-like responses. Behav Brain Res. 2009;198:136–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukkes JL, Mokin MV, Scholl JL, Forster GL. Adult rats exposed to early-life social isolation exhibit increased anxiety and conditioned fear behavior, and altered hormonal stress responses. Horm Behav. 2009;55:248–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shors TJ. Stressful experience and learning across the lifespan. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:55–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Silva Torres IL, Cucco SN, Bassani M, Duarte MS, Silveira PP, Vasconcellos AP, et al. Long-lasting delayed hyperalgesia after chronic restraint stress in rats-effect of morphine administration. Neurosci Res. 2003;45:277–83. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quintero L, Moreno M, Avila C, Arcaya J, Maixner W, Suarez-Roca H. Long-lasting delayed hyperalgesia after subchronic swim stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:449–58. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satoh M, Kuraishi Y, Kawamura M. Effects of intrathecal antibodies to substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide and galanin on repeated cold stress-induced hyperalgesia: Comparison with carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia. Pain. 1992;49:273–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90151-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidal C, Jacob J. Hyperalgesia induced by non-noxious stress in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1982;32:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shabani M, Larizadeh MH, Parsania S, Asadi Shekaari M, Shahrokhi N. Profound destructive effects of adolescent exposure to vincristine accompanied with some sex differences in motor and memory performance. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90:379–86. doi: 10.1139/y11-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Razavinasab M, Shamsizadeh A, Shabani M, Nazeri M, Allahtavakoli M, Asadi-Shekaari M, et al. Pharmacological blockade of TRPV1 receptors modulates the effects of 6-OHDA on motor and cognitive functions in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2013;27:632–40. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geng Y, Byun N, Delpire E. Behavioral analysis of Ste20 kinase SPAK knockout mice. Behav Brain Res. 2010;208:377–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shabani M, Nazeri M, Parsania S, Razavinasab M, Zangiabadi N, Esmaeilpour K, et al. Walnut consumption protects rats against cisplatin-induced neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:1314–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alkire MT, Nathan SV, McReynolds JR. Memory enhancing effect of low-dose sevoflurane does not occur in basolateral amygdala-lesioned rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1167–73. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aghaei I, Shabani M, Doustar N, Nazeri M, Dehpour A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation attenuates motor and cognition impairments induced by bile duct ligation in a rat model of hepatic cirrhosis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;120:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prut L, Belzung C. The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: A review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:3–33. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spuz CA, Borszcz GS. NMDA or Non-NMDA receptor antagonism within the amygdaloid central nucleus suppresses the affective dimension of pain in rats: Evidence for hemispheric synergy. J Pain. 2012;13:328–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood BN, Strong PV, Fleshner M. Lesions of the basolateral amygdala reverse the long-lasting interference with shuttle box escape produced by uncontrollable stress. Behav Brain Res. 2010;211:71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suarez-Roca H, Silva JA, Arcaya JL, Quintero L, Maixner W, Pinerua-Shuhaibar L. Role of mu-opioid and NMDA receptors in the development and maintenance of repeated swim stress-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167:205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang M, Moon C, Chan GC, Yang L, Zheng F, Conti AC, et al. Ca-stimulated type 8 adenylyl cyclase is required for rapid acquisition of novel spatial information and for working/episodic-like memory. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4736–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1177-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Wu Z, Zhou L, Li H, Teng H, Dai W, et al. Deficiency of antinociception and excessive grooming induced by acute immobilization stress in Per1 mutant mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quintero L, Cardenas R, Suarez-Roca H. Stress-induced hyperalgesia is associated with a reduced and delayed GABA inhibitory control that enhances post-synaptic NMDA receptor activation in the spinal cord. Pain. 2011;152:1909–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stocco A, Lebiere C, Anderson JR. Conditional routing of information to the cortex: A model of the basal ganglia's role in cognitive coordination. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:541–74. doi: 10.1037/a0019077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nazeri M, Razavinasab M, Abareghi F, Shabani M. Role of nitric oxide in altered nociception and memory following chronic stress. Physiol Behav. 2014;129:214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suarez-Roca H, Silva JA, Arcaya JL, Quintero L, Maixner W, Pinerua-Shuhaibar L. Role of mu-opioid and NMDA receptors in the development and maintenance of repeated swim stress-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167:205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]