Abstract

The fluorescence of BODIPY and click-BODIPY dyes was found to substantially increase in the presence of bovine serum albumin (BSA). BSA acted as a solubilizer for dye aggregates, in addition to being a conventional binding scaffold for the click-BODIPY dyes, indicating that disaggregation of fluorophores should be considered when evaluating dye-protein interactions.

Graphical Abstract

BSA-induced disaggregation and binding are responsible for a significant fluorescent enhancement upon click-BODIPY dye interaction with BSA

BODIPY dyes are among the most useful and versatile small molecule fluorescent probes, and a wide range of applications has been attributed to the dyes’ high thermal and chemical stabilities, high quantum yields, extinction coefficients, as well as tunable spectroscopic properties.1–3 In regard to biomolecular processes, BODIPY dyes have been primarily used to label ligands to address ligand-receptor interactions.4,5 Recently, several reports suggested that BODIPY dyes could interact directly with a variety of proteins and peptide assemblies, acting as fluorescence-based sensors.6,7

Fluorophore-albumin interactions are of interest, since serum albumins are the major small molecule-binding proteins, which are considered suitable models for various in vitro studies on ligand-protein interactions.8 In addition, due to its size and collection of binding sites, bovine serum albumin (BSA) could be viewed as a viable model for non-specific binding. Although a number of fluorophores have been shown to bind to albumins, only a few BODIPY dyes have been investigated.9–13 Notably, a BODIPY dye was identified (out of a library of 137 dyes) that exhibited ca. 200-fold emission enhancement in the presence of BSA, while exhibiting high specificity towards BSA over serum albumins from other species (human, porcine, rat, and sheep).11,12 Significantly, specifically substituted BODIPY-based fluorescent probes were shown to be viable sensors of protein hydrophobicity.14 Furthermore, several common BODIPY dyes, including a water-soluble derivative, were recently suggested to interact with albumins15 as was evidenced by an increased in the emission intensity.

We previously demonstrated that the incorporation of a triazole moiety on the BODIPY dye scaffold afforded probes that had a significant affinity towards soluble oligomers of amyloid peptides,16 thus illustrating the possibility for click-BODIPY dyes to act as biosensors.

Here, in order to expand on the utility of BODIPY dyes, we examined the interactions between triazole-containing BODIPY dyes, so-called click-BODIPY dyes, (Figure 1) and BSA. The incorporation of the triazole group onto the BODIPY scaffold was accomplished in a straightforward manner using an alkyne-containing BODIPY scaffold.† Dye 2 has a triazole moiety, and the presence of the methyl group, rather than the benzyl group, assures that dye 2 is less hydrophobic than dye 3.

Figure 1.

Structures of krypto-BODIPY (1) and click-BODIPY (2 and 3) dyes.

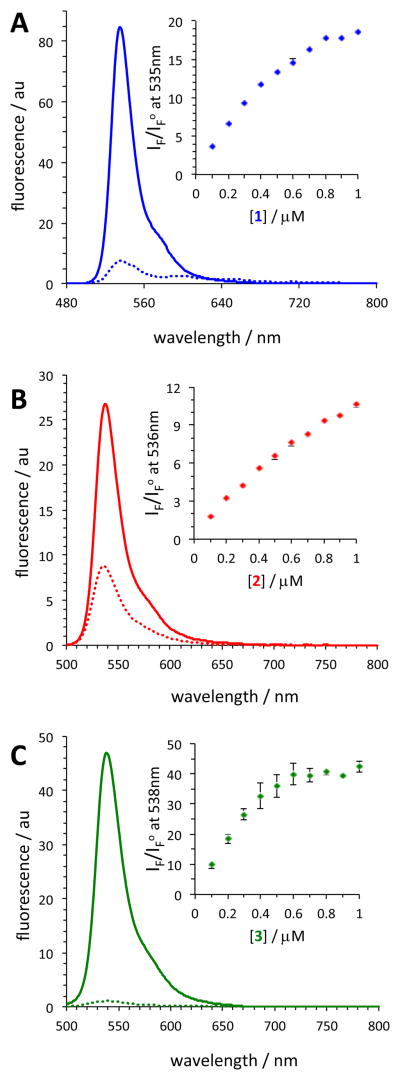

During the initial screening, the fluorescence of dyes 1, 2, and 3 was measured in the presence of a fixed amount of BSA (39.2 μM) and a notable enhancement in the fluorescence of the dyes in the presence of BSA was observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Representative fluorescence spectra of BODIPY dyes (0.5 μM) 1 (A), 2 (B), and 3 (C) in the presence (solid line) and absence (dotted line) of BSA (39.2 μM). λex = 475 nm. Buffer: 10 mM TRIS (0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.4). Insets: fluorescence enhancement as a function of dye concentration; IF – fluorescence in the presence of BSA, IFo – fluorescence in the absence of BSA. The data are the average of 2–3 measurements ± SD.

At the highest experimental dye concentration (1 μM), krypto-BODIPY dye 1 exhibited a ca. 20-fold increase in its fluorescence intensity in the presence of BSA, while the introduction of the methyl-triazole moiety, dye 2, resulted in only a 10-fold increase. Remarkably, in the presence of BSA, dye 3 exhibited a significantly larger enhancement, ca. 40-fold. Notably, the fluorescence enhancement of dye 3 compared to that of dyes 1 and 2 could be viewed as even more remarkable at lower dye concentrations (e.g., 0.2 μM), since the fluorescence of dye 3 saturated at dye concentrations greater than 0.5 μM. It should also be pointed out that the absorption spectra of the dyes were not drastically different in the absence and presence of BSA (Figures S1–S6).

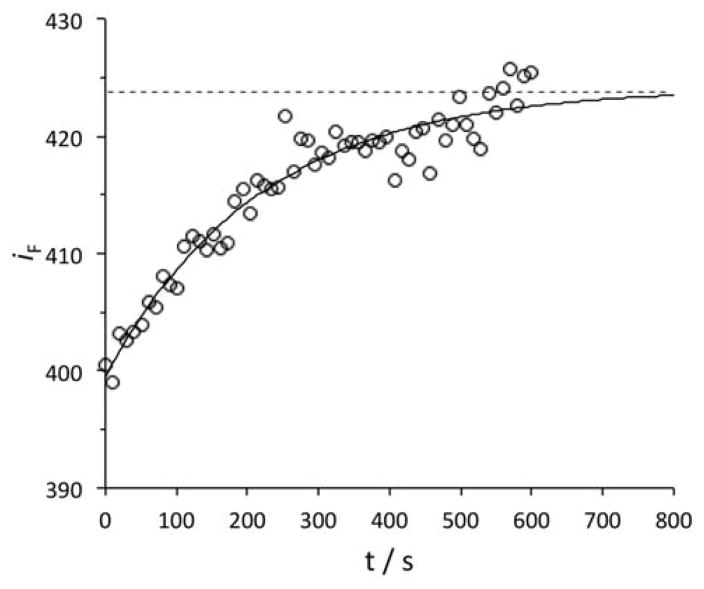

Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity of dye 3, in the presence of BSA, was found to increase with time, t, towards its asymptotic equilibrium value. This was likely related to the kinetics of protein-dye association and the corresponding desolvation effects of the dye and its aggregates. This behavior was not observed in the case of the other two dyes, i.e., no time-dependent increase in the emission was observed upon addition of dyes 1 and 2 to the solution of BSA. For dye 3, the fluorescence intensity at equilibrium, IF(∞) was obtained by fitting the time-dependent fluorescence, iF(t), to the first-order kinetic expression IF(∞)[1−aexp(−bt)], where IF(∞) a, and b are fitting parameters. A representative profile is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Experimental fluorescence intensity of dye 3, iF, as a function of time, t, at CD = 0.3 μM and CP = 8.7 μM (open circles); λex = 530 nm; λem = 538 nm; buffer: 10 mM TRIS (0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.4). The solid curve is a fit through the data using IF(∞)[1−aexp(−bt)]. The dashed horizontal line indicates the obtained value of IF(∞).

The aforementioned observations may be related to the presence of the benzyl group on dye 3, which increases the hydrophobicity of the dye, and as such the dye’s interaction with hydrophobic binding pockets of the protein should be favored. However, the saturation of the fluorescence signal was taking place at dye concentrations of ca. 0.5 μM (Figure 2C). In order to gain insight into the BODIPY-BSA interactions, we carried out more detailed titration experiments at dye concentrations that were below the saturation point using fluorescence spectroscopy.

The titration conditions were chosen such that the total concentration of protein P (CP) was large enough when compared to the total concentration of the dye D (CD). Thus, it could be assumed that only a 1:1 complex of protein–dye (PD), would form appreciably, irrespective of the number of binding sites of BSA. This reversible interaction could be represented as P + D ƒ PD, with the following mass action law (eq. 1):

| (1) |

where K is the corresponding association constant and [P], [D], and [PD] are the concentrations of the three reaction species at equilibrium, which are linked to the total concentrations by the mass balances: CD = [D]+[PD] and CP = [P]+[PD]. To determine K, we examined the effect of CP at a constant CD on the observed fluorescence enhancement, F ≡IF/IFo, where IF and IFo are the fluorescence intensities in the presence and in the absence of BSA, respectively. Assuming that fluorescence intensity is directly proportional to fluorophore concentration, it follows:

| (2) |

where R is the fluorescence ratio of bound to free dye (fluorescence gain) and α is the fraction of bound dye (defined as α ≡ [PD]/CD). Eq. 3 is obtained from the mass balances and eq. 1:

| (3) |

The titrations were performed by varying the protein concentration CP while keeping the dye concentration CD constant at 0.20 μM. The results were subsequently fitted using Eqs. 2 and 3, and the results are shown in Figure 4 and Table 1. The binding constants for all dyes were very similar, and therefore a drastic increase (a 34-fold increase of the fluorescence of the dye 3 as compared to dyes 1 and 2, which showed 1.5 and 2.9 fold increases, respectively) could not be explained by a difference in the binding affinities.

Figure 4.

Experimental fluorescence ratios (F = IF/IFo) as a function of protein concentration, CP, at constant dye concentration, CD = 0.20 μM, for dyes 1 (blue), 2 (red), and 3 (green); ); λex = 530 nm; λem = 538 nm; buffer: 10 mM TRIS (0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.4); the data are the average of 2–3 measurements ± SD. The solid curves are the theoretical fits through the experimental data, obtained using Eqs. 4 and 5.

Table 1.

Binding constants and fluorescent enhancement upon dye binding to BSAa

| dye | K/μM−1 | Rb |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | 0.29 ± 0.15 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 34 ± 1 |

– buffer: 10 mM TRIS (0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.4).

– fluorescence ratio of bound to free dye

The observed saturation in the fluorescence behavior of dye 3 (Figure 2C) required additional explanation. At 0.5 μM of the dye, the protein was present in a large excess as compared to the dye, and the saturation of a binding site was unlikely. We considered the self-aggregation of dye 3 as a competitor to the protein-dye binding in solution. Furthermore, these aggregates were assumed to have a minor contribution to the overall fluorescence, since typically aggregation-induced quenching of fluorescence is reported for the vast majority of fluorophores.17,18

In regard to the dye-BSA interaction, the dye aggregation could be assessed when fluorescence intensity (expressed as IF–IFo, where IFo is the fluorescence intensity of the protein-free system) is plotted as a function of CD at constant CP (Figure 4). At low protein concentrations, IF–IFo reached a plateau as the dye concentration was increased. This plateau decreased as the protein concentration increased. It is important to note that the protein concentration was significantly larger than that of the dye in all cases, which precludes the saturation of the protein’s binding sites. In this case, the protein likely acted as a solubilizer for the dye, and thereby reduced the amount of dye aggregates in solution. Such solubilization by BSA could also explain the disappearance of the plateau in the titration experiments at higher protein concentrations (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Experimental fluorescence intensity difference, IF–IFo, as a function of dye concentration, CD at several protein concentrations, CP (diamonds; the numbers associated with each curve identify the corresponding experimental values of CP in μM. The data are the average of 2–3 measurements ± SD). The solid curves represent IF–IFo calculated using Eqs. 6 and 7 with K = 0.12 μM−1, n = 10, SD = 0.40 μM, and proportionality constant, k = 2600 μM−1. Conditions: λex = 530 nm, λem = 538 nm; buffer: 10 mM TRIS (0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.4).

In order to quantitatively describe the observed behavior, dye reversible aggregation could be represented as nD = Dn, with the following mass action law (Eq. 4):

| (4) |

where, for simplicity, it is assumed that only one monodisperse mesoscopic aggregate, Dn, is formed with aggregation number n, and β is the corresponding association constant. When n ≫ 1, the aggregate could be treated as a separate phase, and SD in Eq. 4 represents the solubility of monomeric D with respect to the aggregates in water.18 For a given n, either β or SD could be equivalently utilized to characterize aggregation thermodynamics. In our case, we choose to use SD due to its more direct graphical identification. Since the contribution of dye aggregates to fluorescence was neglected, the difference in intensity, IF–IFo could be described as follows:

| (5) |

where kF is the proportionality constant describing the effect of free monomeric dye on fluorescence intensity and R = 34 (Table 1). At a given CD, [D] and [D]0 represent the concentrations of free monomeric dye in the presence and absence of BSA, respectively. Note that ([D] − [D]0) is small compared to R [PD] in Eq. 5. The concentrations [PD], [D], and [D]0 can be related to CD and CP by the mass balances:

| (6) |

| (7) |

Eqs. 6 and 7 could be used to numerically calculate [PD], [D], and [D]0 as a function of CD at constant CP provided that K, SD, and n are known. The corresponding IF–IFo curves could then be computed using Eq. 5, assuming that kF is also known. Note that kF is related to the initial slope of the IF–IFo curves (Figure 3), SD to the dye concentration at which the IF–IFo reaches a plateau, and n to the change in the IF–IFo slope as the plateau is approached. To compute IF–IFo curves at the four experimental CP values (Figure 3), we used K = 0.12 μM−1 from Table 1 and set kF = 75 μM−1, n = 10, and SD = 0.40 μM. These curves (Figure 4) were in a satisfactory agreement with our experimental results. It is also important to mention that the experimental value of SD = 0.20 μM used to determine K was well below the “solubility” value, SD.

Conclusions

The interaction of several BODIPY dyes with BSA has been investigated using fluorescence spectroscopy. In the presence of BSA, krypto-BODIPY and click-BODIPY dyes exhibited a notable increase in their fluorescence intensities. In the case of the benzyl-triazole-containing BODIPY dye 3, a drastic increase in the fluorescence intensity was noted, yet the binding affinities for all three dyes towards BSA were found to be virtually the same. The fluorescence enhancement in this particular case demonstrates that BSA could play a dual role: (a) disaggregate the dye’s aggregates and (b) subsequently bind monomeric BODIPY 3. Notably, a similar disaggregation phenomenon was also reported for aza-BODIPY dyes.20 Our results suggest that, at least in some cases, the fluorescence enhancement upon a dye-protein interaction might not be exclusively attributed to the binding event. Potentially the disaggregation of click-BODIPY dyes could be used as a detection event21 as well as a sensor for the hydrophobic surfaces of the proteins.14

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project was partially supported by NIH R15AG038977 from the National Institute On Aging (to SVD) and ACS-PRF 47244-G4 (to OA).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [synthesis and characterization of BODIPY dyes; details on the fluorescent experiments and sample preparations]. See DOI:10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Ulrich G, Ziessel R, Harriman A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1184–1201. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boens N, Leen V, Dehaen W. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:1130–1172. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15132k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loudet A, Burgess K. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4891–4932. doi: 10.1021/cr078381n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kowada T, Maeda H, Kikuchi K. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:4953–4972. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00030k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamkaew A, Lim SH, Lee HB, Kiev LV, Chung LY, Burgess K. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:77–88. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35216h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunahara H, Urano Y, Kojima J, Nagano T. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5597–5604. doi: 10.1021/ja068551y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niu S-l, Ulrich C, Renard P-Y, Romieu A, Ziessel R. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:7229–7242. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertucci C, Domenici E. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:1463–1481. doi: 10.2174/0929867023369673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, Kim HK, Feng S, Vendrell M, Chang YT. Chem Commun. 2011;47:2339–2341. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04495d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komatsu T, Oushiki D, Takeda A, Miyamura M, Ueno T, Terai T, Hanaoka K, Urano Y, Mineno T, Nagano T. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10055–10057. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13367e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vendrell M, Krishna GG, Ghosh KK, Zhai D, Lee JS, Zhu Q, Yau YH, Shochat SG, Kim H, Chung J, Chang YT. Chem Commun. 2011;47:8424–8426. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11774b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Er JC, Tang MK, Chia CG, Liew H, Vendrell M, Chang YT. Chem Sci. 2013;4:2168–2176. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan X, Li P, Li P, Xie T, Yu F, Tang B. Dyes and Pigments. 2011;89:217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorh N, Zhu S, Dhungana KB, Pati R, Luo F-T, Liu H, Tiwari A. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18337. doi: 10.1038/srep18337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marfin Yu S, Aleksakhina EL, Merkushev DA, Rumyantsev EV. J Fluoresc. 2016;26:255–261. doi: 10.1007/s10895-015-1707-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith NW, Alonso A, Brown CM, Dzyuba SV. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1455–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang J, Tang BZ, Liu B. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:2798–2811. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00444b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagarajian R. Surfactant science and technology: retrospect and prospects. Romsted: Laurence; 2014. pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X-X, Wang Z, Yue X, Ma Y, Kiesewetter DO, Chen X. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2010;10:1910–1917. doi: 10.1021/mp3006903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhai D, Xu W, Zhang L, Chang YT. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:2402–2411. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60368g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.