Abstract

Although numerous studies of non-Hispanic whites and blacks show that social integration and social support tend to favor longevity, it is unclear whether this general pattern extends to the Mexican American population. Building on previous research, we employed seven waves of data from the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly to examine the association between perceived social support trajectories and the all-cause mortality risk of older Mexican Americans. Growth mixture estimates revealed three latent classes of support trajectories: high, moderate, and low. Cox regression estimates indicated that older Mexican American men in the low support trajectory tend to exhibit a higher mortality risk than their counterparts in the high support trajectory. Social support trajectories were unrelated to the mortality risk of older Mexican American women. A statistically significant interaction term confirmed that social support was more strongly associated with the mortality risk of men.

Keywords: Social Support, Mortality Risk, Mexican American, Elderly, Gender, H-EPESE

Introduction

For nearly four decades, numerous longitudinal studies have shown that people who report higher levels of social integration (the existence or quantity of social relationships), social engagement (participation in social activities), and social support (the assets derived from social activities and relationships) tend to exhibit lower risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality than people who report lower levels of these important social resources (e.g., Berkman & Syme, 1979; Blazer, 1982; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; House, Robbins, & Metzner 1982; Seeman et al., 1987, 1993; Shoenbach et al., 1986; Shor, Roelfs, & Yogev, 2013; Shye et al., 1995; Thomas, 2012; Wilkins, 2003). Although previous research has made significant contributions to our understanding of the social distribution of mortality risk, several gaps remain. Given that most studies are mainly restricted to samples of non-Hispanic whites and blacks, it is unclear whether the results of previous work extend beyond these populations. Because previous research is generally limited to baseline measures of social resources, we are often forced to assume constant levels over time. It is also unclear whether women or men tend to benefit more or less from social resources.

In this paper, we examine the association between perceived social support trajectories and all-cause mortality risk among older Mexican Americans. We build on previous research in several ways. We expand the external validity of prior work by focusing on Mexican Americans, one of the largest and fastest growing populations in the United States (Angel & Whitfield, 2007; Population Reference Bureau, 2013). We estimate trajectories of perceived social support to assess the degree of exposure over time. We also test whether the association between perceived social support trajectories and mortality risk varies by gender.

In the pages that follow, we examine research concerning social support and mortality risk in the Mexican American population. We also explore potential gender variations in the impact of social support by reviewing relevant empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives. After describing our data, measures, and statistical procedures, we summarize our key findings and conclude with a discussion of the implications of our work.

Theoretical Background

Social Support in the Mexican American Population

Social support is an important resource in the Mexican American population. Studies consistently show that Mexican Americans tend to exhibit high levels of social support (Almeida et al., 2009; Dilworth-Anderson & Marshall, 1996; Farmer et al. 1996; Golding & Baezconde-Garbanati, 1990; Kim & McKenry, 1998; Sena-Rivera, 1979; Vega & Kolody, 1985). Although social support can be derived from a range of social ties and activities, Mexican Americans in general and older Mexican Americans in particular are especially reliant on the family (Almeida et al., 2009; Dilworth-Anderson & Marshall, 1996; Keefe, Padilla, & Carlos, 1979; Kim & McKenry, 1998; Markides, Boldt, & Ray, 1986; Mirande, 1977; Sabogal et al., 1987; Sena-Rivera, 1979; Vaux, 1985; Vega, 1990).

There are three primary explanations for the substantial role of the family in the Mexican American support system. The first explanation is cultural. Numerous studies suggest that the family is highly valued in the Mexican American population (Almeida et al., 2009; Dilworth-Anderson & Marshall, 1996; Golding & Burnam, 1990; Keefe, 1984; Kim & McKenry, 1998; Landale & Oropesa, 2007; Markides, Boldt, & Ray, 1986; Mirande, 1977; Sabogal et al., 1987; Sena-Rivera, 1979; Vaux, 1985; Vega & Kolody, 1985; Vega, 1990). This value or familism is typically expressed through frequent face-to-face interaction, strong family attachments, the primacy of family roles, a collective orientation, and a norm of providing for older generations (Dilworth-Anderson & Marshall, 1996; Flores et al., 2009; Golding & Burnam, 1990; Landale & Oropesa, 2007; Markides, Boldt, & Ray, 1986; Sabogal et al., 1987; Vega, 1990).

The second explanation is structural. Researchers argue that Mexican Americans maintain supportive family ties as an adaptation to disadvantaged positions within broader systems of social stratification (Almeida et al., 2009; Flores et al., 2009; Kim & McKenry, 1998; Landale & Oropesa, 2007). Almeida and colleagues (2009:1856) explain that Mexican Americans “may develop strong support networks among their co-ethnics and extended family as a way of coping with the poverty and discrimination they experience.” The idea is that extended families facilitate the sharing of expenses, the pooling of resources, and the efficient provision of social support.

The final explanation is geographic. Due to the cultural and structural forces mentioned above, Mexican Americans often live in close proximity to other family members (Almeida et al., 2009; Dilworth-Anderson & Marshall, 1996; Golding & Baezconde-Garbanati, 1990; Keefe, Padilla, & Carlos, 1979; Sena-Rivera, 1979). These residential patterns are thought to promote frequent face-to-face interaction and the provision of social support (Almeida et al., 2009; Dilworth-Anderson & Marshall, 1996; Golding & Baezconde-Garbanati, 1990; Keefe, 1984).

Social Support and the Mortality Risk of Mexican American Women and Men

Despite strong family ties and high levels of social support, very few studies have examined the association between social resources and mortality risk in the Mexican American population. Although research suggests that social integration, social engagement, and social support are associated with better mental health, physical health, and health-related behavior in various Hispanic groups (Brown et al., 2009; Finch & Vega, 2003; Gallo et al., 2015; Garcia et al., 2013; Hernandez et al., 2005; Hill et al., 2006, In press; Russell & Taylor, 2009; Vega & Kolody, 1985), we could find only one study focusing on social support and mortality risk in the Mexican American population. In their analysis of data from the Corpus Christi Heart Project, Farmer and colleagues (1996) show that Mexican Americans recovering from heart attacks with low levels of social support (based on an index of marital status, living arrangements, and informational support) exhibit a 238% increase in the risk of mortality as compared to their counterparts with moderate and high levels of social support. The authors also observe a threshold pattern with comparable mortality trends among those respondents with moderate and high levels of social support.

Because Farmer and colleagues (1996) do not consider gender variations in the effects of social support on mortality risk, it is unclear whether Mexican American women or men tend to benefit more or less from social support. In studies of non-Hispanic whites and blacks, there are conflicting reports of gender variations. While several studies show that social integration and social support are more protective among men (Berkman, Vaccarino, & Seeman, 1993; Dalgard & Haheim, 1998; House, Robbins, & Metzner 1982; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Kaplan et al., 1988; Shoenbach et al., 1986; Shye et al., 1995; Wilkins, 2003), there is at least some evidence to suggest that women tend to benefit more (Berkman & Syme, 1979; Forster & Stoller, 1992; Lyyra & Heikkinen, 2006; Seeman et al. 1993). The issue is also complicated by meta-analyses showing no gender differences in the impact of social relationships on mortality risk (Manzoli et al., 2007; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; Shor, Roelfs, & Yogev, 2013).

Although the empirical evidence is mixed, the weight of individual studies suggests that it is important to at least consider the possibility of gender variations. When gender differences are observed, studies are more likely to find that men tend to benefit more than women. Why? We must first acknowledge that because girls and boys are socialized differently, there are clear gender differences in the development of social roles (Shumaker & Hill, 1991; Shye et al., 1995). On the one hand, girls are socialized to be expressive and interpersonal. On the other hand, boys are socialized to be stoic and independent. In adulthood, these differences in socialization often result in women who receive and provide more social support than men (Shumaker & Hill, 1991; Shye et al., 1995).

Since subgroup analyses generally compare women and men at comparable levels of social support, gender differences in the provision of support may be especially important. Shumaker & Hill (1991:108) note that, “for women, large social networks provide greater opportunities for support coupled with more demands and depletion of resources.” Because women tend to have more relationships and more relationship diversity, they may be especially vulnerable to the stress of network demands and caregiving responsibilities (Aneshensel, Pearlin, & Schuler, 1993; Durden, Hill, & Angel, 2007; Kessler, McLeod, & Wethington, 1985; Shumaker & Hill, 1991; Shye et al., 1995; Vaux, 1985). Shye and colleagues (1995:937) explain that these strains “may attach costs to women’s social network participation (in addition to possible benefits) that men do not incur.” According to Shumaker & Hill (1991:108), the benefits of social support may actually be “negated by women’s caregiving roles.”

These gender role processes may be especially pronounced in the Mexican American population and among older adults. The Mexican American family is often (but not always) characterized by a traditional structure that is patriarchal and authoritarian (Baca Zinn & Pok, 2002; Flores et al., 2009; Gowan & Trevino 1998; Landale & Oropesa, 2007; Markides, Boldt, & Ray, 1986; Mirande, 1977; Sena-Rivera, 1979). Under these unique cultural conditions, gender roles are often (but not always) conservative, and the woman is expected to be “first and foremost a self-sacrificing wife and mother” (Gowan & Trevino 1998:1081). To the extent that these cultural expectations lead to greater network demands and caregiving responsibilities, Mexican American women (especially older women who tend to be more conservative) may be more likely than Mexican American men to experience the conflicting “costs” of social network participation.

Hypotheses

Drawing on this theoretical background, we developed two hypotheses to guide our analyses. Hypothesis 1: More favorable trajectories of perceived social support will be associated with lower mortality risk. Hypothesis 2: Trajectories of perceived social support will be more strongly associated with mortality risk among men.

Methods

Data

To formally test these hypotheses, we employ seven waves of data collected from the original cohort of the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (H-EPESE) (http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/2851/detail). The baseline H-EPESE survey is based on a probability sample of 3,050 Mexican Americans aged 65 and older who reside in Texas, California, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. The response rate at baseline was 86%. Respondents were surveyed in 1993−1994, 1995−1996, 1998−1999, 2000−2001, 2004−2005, 2007, and 2010. The surveys included detailed information on social relationships, health and disability, immigration history, and demographic characteristics. Due to missing data over the seventeen-year study period, our final analytic sample includes 2,334 respondents. Table 1 provides baseline descriptive statistics for the study sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (H-EPESE, 1993)

| Full Sample (n = 2,334) |

Women (n = 1,357) |

Men (n = 977) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Deceased | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.77 |

| Low Support Trajectory | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Moderate Support Trajectory | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| High Support Trajectory | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| Age | 73.07 (6.79) | 73.09 (6.85) | 73.04 (6.70) |

| Women | 0.58 | --- | --- |

| Immigrant | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.45 |

| Education (≥High School) | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| Household Income (≤ $9,999) | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| Social Disengagement | 1.96 (1.05) | 2.13 (1.05) | 1.72 (1.00) |

| Social Support (Baseline) | 1.63 (0.58) | 1.66 (0.59) | 1.59 (0.66) |

| Never Smoked | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.39 |

| Former Smoker | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.43 |

| Current Smoker | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| Heavy Drinker | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.36 |

| Depression (CES-D) | 14.92 (7.03) | 15.72 (7.57) | 13.84 (6.07) |

| Cognitive Function (MMSE) | 24.71 (4.55) | 24.60 (4.64) | 24.86 (4.42) |

| Chronic Conditions | 0.88 (0.90) | 0.92 (0.88) | 0.83 (0.92) |

| Mobility (POMA) | 6.48 (3.52) | 6.12 (3.46) | 6.98 (3.54) |

Notes: H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly. Shown are means and standard deviations (in parentheses). CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic-Depression Scale. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam. POMA = Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment.

Measures

Mortality Risk

We assess mortality risk over 17 years using the H-EPESE follow-up procedures. Deaths were confirmed by a search of the National Death Index and, to a lesser extent, by proxy reports. Survival time was defined as the number of days between the baseline interview and the date of death or final interview, at which point surviving participants represent censored observations.

Social Support

Social support can be defined as the actual receipt of resources and as individual perceptions of resource availability (House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988; Rote, Hill, & Ellison, 2013; Uchino, 2004). In this study, social support refers to perceptions of emotional and instrumental support and is measured as the mean response to two items. Respondents were asked, “In times of trouble, can you count on at least some of your family or friends?” Respondents were also asked, “Can you talk about your deepest problems with at least some of your family or friends?” Response categories for these items were coded (0) hardly ever, (1) some of the time, or (2) most of the time. An exploratory principal components analysis with varimax rotation produced a single factor, with loadings of 0.94 for both items at baseline. A reliability analysis also suggests adequate internal consistency for two items (α = 0.86). Following recent analyses of social engagement trajectories (Thomas, 2012), we use the social support measures at each wave to estimate social support trajectories (described below). We also adjust for baseline levels of social support.

Social Disengagement

We assess the structural basis of social support by adjusting for indicators of social integration and social engagement (House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988; Rote, Hill, & Ellison, 2013; Seeman & Berkman, 1988), including marital status, living arrangements, monthly contact with family and friends, religious attendance, and secular group memberships. We coded marital status (1) for unmarried and (0) otherwise. Monthly contact with family and friends is coded (1) for no monthly contact and (0) otherwise. Living arrangements are coded (1) for living alone and (0) otherwise. Religious attendance is coded (1) for never or almost never attending mass or services and (0) otherwise. Secular group memberships are coded (1) for no memberships and as (0) otherwise. To simplify our presentation, we created an index of social disengagement by summing across the five items (Bassuk, Glass, & Berkman, 1999; Hill et al., 2006; Thomas, 2012).

Health and Health Behavior

In order to account for health selection into more favorable social support trajectories, subsequent analyses control for indicators of mental health, physical health, and health-related behavior. We evaluate health behavior with measures of smoking and problem drinking (House, Robbins, & Metzner 1982; Seeman at al., 1987, Thomas, 2012). We measure smoking behavior with a single item. Respondents were asked, “Do you smoke cigarettes now?” We coded smoking into dummy variables for (a) current smoker, (b) former smoker, and (c) never smoked (the reference category). Response categories for this item were coded (1) for current smoker and (0) otherwise. We use the Cut, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye Opener (CAGE) questionnaire to measure heavy drinking and drinking problems (Ewing, 1984). The CAGE instrument measures responses to four questions: (a) “Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?” (b) “Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?” (c) “Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking?” (d) “Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover (eye opener)?” Following the work of Saitz and colleagues (1999), respondents who answered “yes” to any of the four questions were coded (1) for problem drinker and (0) otherwise.

We assess mental health with measures of depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning (Blazer, 1982; Lyyra & Heikkinen, 2006; Wilkins, 2003). To assess depressive symptoms, we use the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D). The CES-D measures responses to 20 items (Radloff, 1977). Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced in the past week. We coded the original response categories for these items as (1) rarely or none of the time, (2) some of the time, (3) occasionally, or (4) most or all of the time. The final CES-D measure represents a summed index of the twenty items. We use the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to measure cognitive functioning. The MMSE is one of the most commonly used screening devices in studies of older adults. It represents a brief, standardized method by which to grade cognitive status (Folstein et al., 1975). It measures responses to a standard battery of memory and reasoning items and assesses orientation, attention, immediate and short-term recall, language, and the ability to follow simple verbal and written commands. Following previous research (Hill et al., 2006, 2012), we use the continuous specification of the MMSE to represent the full range scores.

We evaluate physical health with measures of chronic disease burden and functional mobility (Blazer, 1982; Lyyra & Heikkinen, 2006; Thomas, 2012). We assess disease burden by summing the number of chronic conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and heart attack. Our measures of these conditions are based on self-reports. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever been told by a doctor that they had any of the aforementioned conditions. We coded the response categories for these items (1) for yes and (0) otherwise. We use the performance-oriented mobility assessment (POMA) to assess functional mobility. The POMA is based on three tasks: standing balance (semi-tandem and side by side), a timed 8-ft walk at a normal pace (gait speed), and a timed test of five repetitions of rising from a chair and sitting down (Guralnik et al., 1995). Following the work of Markides and colleagues (2001), assessments were coded as (0) unable to complete task, (1) poor, (2) moderate, (3) good, or (4) best. Respondents who received a score of (0) include those who were unable to complete the task and those who did not attempt the task for safety reasons. The final POMA measure represents a summed index of the four items.

Background Factors

Several background factors have been identified as significant correlates of social support (Almeida et al., 2009; Rote, Hill, & Ellison, 2013; Seeman & Berkman, 1988) and mortality risk (Hill et al., 2005; House, Robbins, & Metzner 1982; Seeman at al., 1987, Thomas, 2012). In accordance with this body of research, subsequent multivariate analyses include controls for age, gender, immigrant status, education, and household income. Age is a continuous variable, ranging from (65) to (107). Gender is coded (1) for women and (0) for men. Immigrant status is coded (1) for immigrant and (0) for those born in the US. Education is coded (1) for high school diploma or greater and (0) otherwise. Household income is coded (1) for ≤ $9,999 and (0) otherwise.

Statistical Procedures

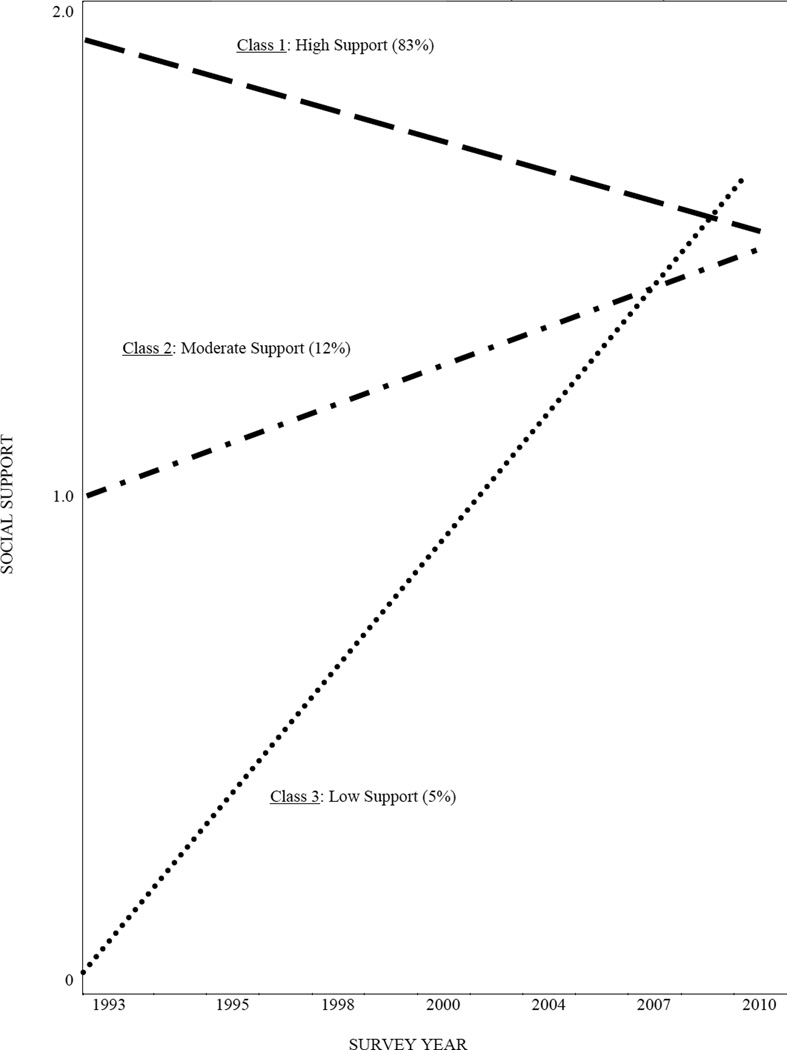

Our focal analyses were conducted in three steps. We first used the growth mixture modeling (GMM) application in Mplus 6.0 to estimate classes of social support trajectories across the seven waves of data (Figure 1). GMM allows for the identification of multiple latent subpopulations of longitudinal change (Jung & Wickrama, 2008; Ram & Grimm, 2009). Ram and Grimm (2009) explain that “the objective of the growth mixture model is to describe differences in how longitudinal change proceeds in subsamples within the data” (pg. 566). The key question driving this analysis is whether the data are more accurately represented by a single social support trajectory or multiple support trajectories.

Figure 1.

Social Support Trajectory Classes (H-EPESE, 1993–2010)

Once we established that multiple latent subpopulations existed in the data, we sought to describe the data in greater detail, to determine which groups of respondents tend to belong to which classes of social support trajectories. To accomplish this, we estimated a series of bivariate multinomial logistic regression models to assess whether membership in the social support trajectory classes varies according to our focal variables (Table 2). Finally, we estimated a series of Cox proportional hazard regression models to estimate the relative risk of mortality as a function of the social support trajectory classes and baseline control variables (Table 3). More specifically, we modeled the prediction of mortality risk for the full sample and separately for women and men. In our analysis of the full sample, we test an interaction term (social support*gender) to formally assess whether the effects of the social support trajectories on mortality risk vary for women and men.

Table 2.

Bivariate Multinomial Logistic Regressions of Social Support Trajectories (H-EPESE, 1993-2010)

| Full Sample (n = 2,334) |

Women (n = 1,357) |

Men (n = 977) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low vs. High |

Moderate vs. High |

Low vs. High |

Moderate vs. High |

Low vs. High |

Moderate vs. High |

|

| Age | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) |

1.01 (0.99, 1.03) |

1.03 (0.99, 1.07) |

1.02 (0.99, 1.05) |

1.01 (0.97, 1.05) |

1.01 (0.97, 1.04) |

| Women | 0.68* (0.48, 0.96) |

0.79 (0.61, 1.02) |

--- | --- | --- | --- |

| Immigrant | 2.02* (1.42, 2.88) |

0.96 (0.74, 1.26) |

2.43* (1.47, 4.03) |

1.01 (0.70, 1.45) |

1.66* (1.01, 2.73) |

0.90 (0.61, 1.34) |

| Education (≥High School) | 0.60 (0.30, 1.21) |

0.81 (0.51, 1.29) |

0.77 (0.30, 1.95) |

0.77 (0.39, 1.50) |

0.45 (0.16, 1.27) |

0.83 (0.44, 1.56) |

| Household Inc. (≤ $9,999) | 2.13* (1.46, 3.11) |

1.07 (0.82, 1.39) |

2.92* (1.60, 5.31) |

1.01 (0.70, 1.45) |

1.86* (1.12, 3.08) |

1.20 (0.82, 1.77) |

| Social Disengagement | 2.27* (1.92, 2.69) |

1.40* (1.24, 1.59) |

1.93* (1.51, 2.46) |

1.36* (1.13, 1.62) |

2.83* (2.25, 3.56) |

1.60* (1.33, 1.92) |

| Social Support (Baseline) | 0.21* (0.17, 0.27) |

0.41* (0.34, 0.49) |

0.23* (0.16, 0.31) |

0.34* (0.27, 0.44) |

0.21* (0.15, 0.29) |

0.51* (0.39, 0.67) |

| Former Smoker | 1.13 (0.75, 1.69) |

0.93 (0.69, 1.27) |

1.17 (0.63, 2.18) |

0.76 (0.46, 1.26) |

0.90 (0.51, 1.60) |

0.99 (0.63, 1.56) |

| Current Smoker | 1.87* (1.17, 2.99) |

1.70* (1.19, 2.44) |

1.57 (0.72, 3.42) |

1.25 (0.69, 2.26) |

1.69 (0.89, 3.20) |

1.94* (1.17, 3.20) |

| Heavy Drinker | 1.73* (1.16, 2.57) |

1.40* (1.02, 1.91) |

1.37 (0.41, 4.55) |

1.37 (0.57, 3.29) |

1.54 (1.94, 2.53) |

1.27 (0.86, 1.87) |

| Depression (CES-D) | 1.03* (1.01, 1.05) |

1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

1.05* (1.02, 1.08) |

1.01 (0.99, 1.03) |

1.01 (0.98, 1.05) |

1.00 (0.97, 1.03) |

| Cognitive Fun. (MMSE) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) |

0.99 (0.96, 1.03) |

0.98 (0.94, 1.03) |

0.99 (0.92, 1.05) |

0.98 (0.91, 1.04) |

0.99 (0.94, 1.04) |

| Chronic Conditions | 0.93 (0.76, 1.15) |

0.93 (0.79, 1.08) |

1.12 (0.85, 1.49) |

0.91 (0.74, 1.13) |

0.79 (0.58, 1.07) |

0.95 (0.76, 1.19) |

| Mobility (POMA) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) |

1.04 (0.99, 1.09) |

1.05 (0.97, 1.15) |

1.03 (0.97, 1.09) |

1.01 (0.94, 1.10) |

1.05 (0.98, 1.12) |

Notes: H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly. Shown are odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

p < .05.

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic-Depression Scale. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam. POMA = Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment.

Table 3.

Cox Regressions of All-Cause Mortality by Social Support Trajectories (H-EPESE, 1993–2010)

| Full Sample (n = 2,334) |

Women (n = 1,357) |

Men (n = 977) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Support Trajectory | 1.70 (1.24, 2.31) |

** | 1.13 (0.82, 1.54) |

1.40 (1.01, 1.93) |

* | |

| Moderate Support Trajectory | 0.92 (0.71, 1.21) |

0.95 (0.75, 1.19) |

0.91 (0.72, 1.15) |

|||

| Low Support Trajectory*Women | 0.82 (0.71, 0.96) |

* | --- | --- | ||

| Moderate Support Trajectory*Women | 1.01 (0.89, 1.13) |

--- | --- | |||

| Age | 1.08 (1.07, 1.09) |

*** | 1.08 (1.07, 1.09) |

*** | 1.08 (1.07, 1.10) |

*** |

| Women | 0.69 (0.61, 0.78) |

*** | --- | --- | ||

| Immigrant | 0.82 (0.74, 0.91) |

*** | 0.80 (0.70, 0.92) |

** | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) |

* |

| Education (≥High School) | 0.91 (0.76, 1.10) |

0.99 (0.77, 1.28) |

0.83 (0.64, 1.09) |

|||

| Household Income (≤ $9,999) | 0.90 (0.81, 1.03) |

0.88 (0.76, 1.01) |

0.95 (0.81, 1.12) |

|||

| Social Disengagement | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) |

1.05 (0.98, 1.13) |

1.06 (0.98, 1.15) |

|||

| Social Support (Baseline) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.08) |

0.98 (0.87, 1.11) |

1.01 (0.90, 1.14) |

|||

| Former Smoker | 1.07 (0.95, 1.21) |

0.98 (0.82, 1.16) |

1.16 (0.98, 1.39) |

|||

| Current Smoker | 1.49 (1.28, 1.74) |

*** | 1.53 (1.22, 1.93) |

*** | 1.52 (1.22, 1.89) |

*** |

| Heavy Drinker | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) |

0.93 (0.63, 1.38) |

0.96 (0.81, 1.13) |

|||

| Depression (CES-D) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) |

* | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) |

** | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) |

|

| Cognitive Function (MMSE) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) |

** | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) |

** | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) |

|

| Chronic Conditions | 1.29 (1.22, 1.36) |

*** | 1.29 (1.19, 1.39) |

*** | 1.31 (1.21, 1.42) |

*** |

| Mobility (POMA) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) |

*** | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) |

*** | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) |

** |

Notes: H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly.

Shown are hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

The reference group for low and moderate social support is high social support.

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic-Depression Scale.

MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam.

POMA = Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment.

We recognize that many of the variables that we frame as “control variables” could also be re-framed as mediators or mechanisms of social support (e.g., Berkman et al. 2000; Cobb, 1976; House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; Seeman, 1996; Uchino 2004, Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996; Umberson, 1987; Umberson & Montez, 2010; Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010). Indeed, previous mortality studies have been critiqued for potentially underestimating the protective effects of social support (Uchino, 2004). However, as preliminary analyses showed no substantive differences in the effects of social support with progressive adjustments for control variables, our presentation in Table 3 has been restricted to our final (fully adjusted) models.

Missing Data

Due to missing data, our analytic sample size is reduced from 3,050 respondents to 2,334 respondents. One reason for our missing data is that the social support questions were not administered to proxy respondents (n = 316). Another reason is listwise deletion of baseline control variables (n = 400). We employ full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to address our missing data when estimating our social support trajectory classes in Mplus. Through the use of FIML, we are able retain respondents with missing data without imputation. Several detailed methodological treatments have described the statistical benefits of FIML (e.g., Enders, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002; Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010). As an added precaution, we conducted a supplemental robustness check by assigning all missing cases to the low social support trajectory class (classes described below). The results of these analyses (not shown) are substantively identical to our analyses with missing data.

Results

GMM Analyses

To determine the appropriate number of social support trajectory classes, we fitted three consecutive GMM models. Our first model specified two social support trajectory classes and resulted in a Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) of 16047.40 and a LO-MENDELL-RUBIN ADJUSTED LRT TEST (LMR-LRT) of 863.31 (p<0.001). The statistically significant LMR-LRT suggested that the two-trajectory model fitted the data better than the one-trajectory model. Our second model specified three social support trajectory classes and resulted in a BIC of 14850.52 and a LMR-LRT of 1171.73 (p<0.001). Again, the statistically significant LMR-LRT suggested that the three-trajectory model fitted the data better than the initial two-trajectory model. Our final model specified four social support trajectory classes and resulted in a BIC of 12581.69 and a LMR-LRT of 2200.62 (p<0.10). We eventually selected the three-class model because the LMR-LRT for the four-class model was not statistically significant at conventional levels (suggesting no improvement in model fit over the three-trajectory model). The three-class model also resulted in the lowest BIC and an adequate (close to 1.0) entropy value of 0.91.

Figure 1 presents a graphical illustration of the three social support trajectory classes. The three trajectories may be interpreted as high social support, moderate social support, and low social support. The first trajectory class (high support) represent 83% of the sample. The second trajectory class (moderate support) represent 12% of the sample. The third trajectory class (low support) represent 5% of the sample. Respondents in the high support class exhibit high initial levels of social support and slight losses of support over time. Respondents in this class maintain high to moderately high levels of social support over the entire study period (approximately 17 years). Respondents in the moderate social support class exhibit moderate initial levels and slight improvements over time. Respondents in this class maintain moderate to moderately high levels of social support over the study period. Despite very low initial levels of social support, respondents in the low support class exhibit a significant mobilization of support over the study period. By the final wave (2010), all three social support classes appeared to converge at moderately high levels of support.

Bivariate Analyses

Table 2 presents odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals obtained from a series of bivariate multinomial logistic regressions. We first predicted membership in the low and moderate social support trajectories (with membership in the high social support class serving as the common reference group) in the full sample. We then replicated this analysis for women and men.

The odds of membership in the low support trajectory class were higher for immigrants (full sample, women, and men), those who reported less than $10,000 in household income (full sample, women, and men), disengaged respondents (full sample, women, and men), current smokers (full sample only), heavy drinkers (full sample only), and those who reported more symptoms of depression (full sample and women). The odds of membership in the low support trajectory class were lower for women and respondents with higher levels of baseline social support (full sample, women, and men).

The odds of membership in the moderate support trajectory class were higher for disengaged respondents (full sample, women, and men), current smokers (full sample and men), and heavy drinkers (full sample only). The odds of membership in the moderate support trajectory class were lower for respondents with higher levels of baseline social support (full sample, women, and men).

Not surprisingly, indicators of social integration and social engagement (not including secular group membership) were among the strongest predictors of membership in the support trajectory classes. In the full sample and for women and men, membership in the support trajectory classes did not vary according to age, education, cognitive status, number of chronic conditions, or mobility level. These results suggest that age and health status were among the weakest predictors of membership in the support trajectory classes. Overall, women and respondents with higher baseline levels of social support tended to exhibit the most favorable social support trajectories. Respondents who reported low levels of income, higher levels of disengagement, and unhealthy lifestyles tended to exhibit the least favorable social support trajectories.

Multivariate Analyses

Table 3 presents hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals obtained from a series of Cox regressions predicting mortality risk. Following the analytic strategy in Table 2, we predicted mortality risk in the full sample and separately for women and men. In the full sample and for women and men, respectively, the mortality risk of respondents in the moderate social support trajectory was comparable to the mortality risk of respondents in the high social support trajectory. For women, mortality risk did not vary according to social support trajectory classification.

In the full sample, respondents classified in the low social support trajectory tended to exhibit a higher mortality risk than respondents classified in the high social support trajectory. The corresponding hazard ratio (HR = 1.70) indicates that the mortality risk is 70% higher for respondents in the low social support trajectory. This general pattern applied only to men. For men, the hazard ratio (HR = 1.40) indicates that the mortality risk is 40% higher for respondents in the low social support trajectory. The interaction term (low social support*women) confirmed that the effect of membership in the low social support trajectory was more strongly associated with the mortality risk of men.

In addition to our focal results, we observed that mortality risk was higher for older respondents (full sample, women, and men), current smokers (full sample, women, and men), respondents with higher levels of depression (full sample and women), and respondents with more chronic conditions (full sample, women, and men). We also found that mortality risk was lower for women, immigrants (full sample, women, and men), and respondents with better cognitive functioning (full sample and women) and mobility (full sample, women, and men). In the full sample and for women and men, mortality risk did not vary according to education, income, disengagement, support, or alcohol consumption.

Discussion

Although numerous studies of non-Hispanic whites and blacks show that social support tends to favor longevity, it is unclear whether this general pattern extends to the Mexican American population. Building on previous research, we employed seven waves of H-EPESE data to examine the association between perceived social support trajectories and the all-cause mortality risk of older Mexican Americans. We also formally tested whether the effects of the perceived social support trajectories varies by gender.

Initial growth mixture estimates revealed three latent classes of support trajectories: high support, moderate support, and low support. Most respondents were classified in the high support trajectory class. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that Mexican Americans tend to have large family networks and high levels of social support within those networks (Almeida et al., 2009; Dilworth-Anderson & Marshall, 1996; Farmer et al. 1996; Golding & Baezconde-Garbanati, 1990; Kim & McKenry, 1998; Sena-Rivera, 1979; Vega& Kolody, 1985). To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to identify multiple latent social support trajectories in the Mexican American population.

Our first hypothesis stated that more favorable trajectories of perceived social support would be associated with lower mortality risk. This hypothesis received mixed support. In the full sample, respondents classified in the low social support trajectory exhibited a higher mortality risk than respondents classified in the high social support trajectory. However, the mortality risk of respondents in the moderate social support trajectory was comparable to the mortality risk of respondents in the high social support trajectory. Our results contrasting the low and high social support trajectories confirm that social support is associated with lower mortality risk in the Mexican American population (Farmer et al. 1996). Our results contrasting the moderate and high social support trajectories suggest a threshold effect, which is consistent with earlier studies of Mexican Americans (Farmer et al. 1996) and non-Hispanic blacks and whites (e.g., Blazer, 1982; Hanson et al., 1989; Kaplan et al. 1988; Orth-Gomer & Johnson, 1987; Shoenbach et al., 1986). Building on previous work, we are the first to establish a link between social support trajectories and mortality risk in a community-based sample of Mexican Americans.

Our second hypothesis stated that the social support trajectories would be more strongly associated with mortality risk among men. This hypothesis was supported. On the one hand, older Mexican American men assigned to the low social support trajectory exhibited a higher mortality risk than their counterparts assigned to the high social support trajectory. On the other hand, social support trajectories were unrelated to the mortality risk of women. A statistically significant interaction term established that social support was more strongly associated with the mortality risk of men. These results confirm previous studies of non-Hispanic whites and blacks, showing that social integration and social support can be more protective among men (Berkman, Vaccarino, & Seeman, 1993; Dalgard & Haheim, 1998; House, Robbins, & Metzner 1982; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Kaplan et al., 1988; Shoenbach et al., 1986; Shye et al., 1995; Wilkins, 2003). Although not a direct test, these results are consistent with a theory of traditional Mexican American culture (Baca Zinn & Pok, 2002; Gowan & Trevino 1998; Landale & Oropesa, 2007; Markides, Boldt, & Ray, 1986; Mirande, 1977; Sena-Rivera, 1979) and gendered differential vulnerability to relationship strain (Shumaker & Hill, 1991; Shye et al., 1995). To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to document gender variations in the link between social support trajectories and mortality risk in the Mexican American population.

The primary limitation of the present study is our assessment of social support. Although our two-item social support index shows sufficient construct validity and adequate reliability, content validity is low. The two items appear to indicate instrumental and emotional support, but several other important dimensions of social support (e.g., informational support, tangible support, and belonging) are unmeasured. Because the content validity of our social support index is low, our mortality estimates may be conservative. A second limitation is our assessment of social support trajectories. Although our trajectory analyses represent an advance over static baseline measures of social support, discrete trajectory classification “ignores the interindividual heterogeneity around each trajectory class” (Thomas, 2012:562). By clustering individual trajectories, the GMM procedure necessarily restricts our interpretation to differences in social support trajectory classes. Having said this, we have no reason to expect that focusing on interindividual differences in social support trajectories would substantively alter our general conclusions.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that social support is associated with lower mortality risk among older Mexican American men. As we move forward, we need to establish the mechanisms through which social support might favor longevity in the elderly Mexican American population. Our analyses included several “control variables” that have been framed as mediator variables (e.g., health behaviors and mental health) in previous work; however, these measures failed to explain any of the effects of social support through progressive adjustment. This should remind us that we have only begun to consider the effects of social support on the health and longevity of Mexican Americans. It is vital for future research to develop unique theoretical models to better understand the role of social support in diverse populations. It is also unclear why men tend to benefit more from social support than women. To formally test the theory developed in this paper, we need direct assessments of the particular relationship demands of women and men. Research along these lines would make a significant contribution to our understanding of gender variations in the association between social support and mortality risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by the NIH National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 MD005894-01) and the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG10939-10).

Biographies

Terrence D. Hill is an associate professor of Sociology at the University of Arizona. His research focuses on the social distribution of health and health-relevant behaviors. He is especially interested in the effects of social relationships, religious involvement, neighborhood conditions, and socioeconomic status.

Bert N. Uchino is a professor of Psychology at the University of Utah. His research focuses on the link between social relationships and health, especially the underlying psychological and biological mechanisms.

Jessica L. Eckhardt is a PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of Utah. She studies the social determinants of health, environmental sociology, and how environmental quality affects health outcomes and disparities. Her dissertation examines and tests various environmental health inequality frameworks.

Jacqueline L. Angel is a professor of Public Affairs and Sociology and a Faculty Affiliate at the Population Research Center and LBJ School Center for Health and Social Policy at The University of Texas at Austin. Her research addresses inequality and health issues across the life course of Latinos.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Terrence D. Hill, Department of Sociology, The University of Arizona, tdhill@email.arizona.edu

Bert N. Uchino, Department of Psychology, The University of Utah, bert.uchino@psych.utah.edu

Jessica L. Eckhardt, Department of Sociology, The University of Utah, jessica.eckhardt@soc.utah.edu

Jacqueline L. Angel, School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin, jangel@mail.utexas.edu

References

- Almeida J, Molnar BE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1852–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Schuler RH. Stress, role captivity, and the cessation of caregiving. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:54–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel J, Whitfield K. The health of aging Hispanics: The Mexican-origin population. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M, Pok AYH. Tradition and transition in Mexican-origin families. In: Taylor R, editor. Minority families in the United States. Uppersaddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. (pp. 79-00) [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;131:165–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Vaccarino V, Seeman T. Gender differences in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: The contribution of social networks and support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1993;15:112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG. Social support and mortality in an elderly community population. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1982;115:684–694. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SC, Mason CA, Lombard JL, Martinez F, Plater-Zyberk E, Spokane AR, Szapocznik J. The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of ‘eyes on the street.’. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;64B:234–246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. Presidential Address-1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1975;38:300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard OS, Håheim LL. Psychosocial risk factors and mortality: A prospective study with special focus on social support, social participation, and locus of control in Norway. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52:476–481. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.8.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Marshall S. Social support in its cultural context. In: Pierce G, Sarason B, Sarason I, editors. Handbook of social support and the family. New York: Springer; 1996. pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Durden E, Hill T, Angel R. Social demands, social supports, and psychological distress among low-income women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing J. Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer IP, Meyer PS, Ramsey DJ, Goff DC, Wear ML, Labarthe DR, Nichaman MZ. Higher levels of social support predict greater survival following acute myocardial infarction: The Corpus Christi Heart Project. Behavioral Medicine. 1996;22:59–66. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1996.9933765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores YG, Hinton L, Franz CE, Barker JC, Velasquez A. Beyond familism: Ethics of care of Latina caregivers of elderly parents with dementia. Health Care for Women International. 2009;30:1055–1072. doi: 10.1080/07399330903141252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. ‘Mini-Mental State’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster LE, Stoller EP. The impact of social support on mortality: A seven-year follow-up of older men and women. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1992;11:173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Fortmann AL, McCurley JL, Isasi CR, Penedo FJ, Daviglus ML, Carnethon MR. Associations of structural and functional social support with diabetes prevalence in US Hispanics/Latinos: Results from the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;38:160–170. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9588-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G, Ellison CG, Sunil TS, Hill TD. Religion and selected health behaviors among Latinos in Texas. Journal of Religion and Health. 2013;52:18–31. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM, Burnam MA. Stress and social support as predictors of depressive symptoms in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:268–287. [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM, Baezconde-Garbanati LA. Ethnicity, culture, and social resources. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:465–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00938118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowan M, Trevino M. An examination of gender differences in Mexican-American attitudes toward family and career roles. Sex Roles. 1998;38:1079–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J, Ferrucci L, Simonsick E, Salive M, Wallace R. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332:556–562. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson BS, Isacsson SO, Janzon L, Lindell SE. Social network and social support influence mortality in elderly men prospective population study of ‘Men Born In 1914,’ Malmö, Sweden. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1989;130:100–111. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Plant EA, Sachs-Ericsson N, Joiner TE., Jr Mental health among Hispanics and Caucasians: risk and protective factors contributing to prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:844–860. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T, Angel J, Ellison C, Angel R. Religious attendance and mortality: An 8-year follow-up of older Mexican Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2005;60B:S102–S109. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.s102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T, Burdette A, Angel J, Angel R. Religious attendance and cognitive functioning among older Mexican Americans. The Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61B:P3–P9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T, Angel J, Balistreri K, Herrera A. Immigration status and cognitive functioning in late life: An examination of gender variations in the healthy immigrant effect. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75:2076–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T, Burdette A, Taylor J, Angel J. Religious attendance and the mobility trajectories of older Mexican Americans. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. doi: 10.1177/0022146515627850. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7:2–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Robbins C, Metzner HL. The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1982;116:123–140. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology. 1988;14:293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama K. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Cohen RD, Brand RJ, Syme SL, Puska P. Social connections and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease: Prospective evidence from eastern Finland. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;128:370–380. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe SE, Padilla AM, Carlos ML. The Mexican-American extended family as an emotional support system. Human Organization. 1979;38:144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe SE. Real and ideal extended familism among Mexican Americans and Anglo Americans: On the meaning of “close” family ties. Human organization. 1984;43:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLeod JD, Wethington E. The costs of caring: A perspective on the relationship between sex and psychological distress. In: Sarason I, Sarason B, editors. Social support: Theory, research and applications. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1985. pp. 491–506. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, McKenry PC. Social networks and support: a comparison of African Americans, Asian Americans, Caucasians, and Hispanics. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1998;29:313–334. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Hispanic families: Stability and change. Annual Review of Sociology. 2007;33:381–405. [Google Scholar]

- Lyyra TM, Heikkinen RL. Perceived social support and mortality in older people. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:S147–S152. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.s147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoli L, Villari P, M Pirone G, Boccia A. Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Boldt JS, Ray LA. Sources of helping and intergenerational solidarity: A three-generations study of Mexican Americans. Journal of Gerontology. 1986;41:506–511. doi: 10.1093/geronj/41.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides K, Black S, Ostir G, Angel R, Guralnik J, Lichtenstein M. Lower body function and mortality in Mexican American elderly people. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56:M243–M247. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.4.m243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirande A. The Chicano family: A reanalysis of conflicting views. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1977;39:747–756. [Google Scholar]

- Orth-Gomer K, Johnson JV. Social network interaction and mortality: A six year follow-up study of a random sample of the Swedish population. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:949–957. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm K. Growth mixture modeling: A method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:565–576. doi: 10.1177/0165025409343765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rote S, Hill T, Ellison C. Religious attendance and loneliness in later life. The Gerontologist. 2013;53:39–50. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Taylor J. Living alone and depressive symptoms: the influence of gender, physical disability, and social support among Hispanic and non-Hispanic older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;64:95–104. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Lepore M, Sullivan L, Amaro H, Samet J. Alcohol abuse and dependence in Latinos living in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159:718–724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA. Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0018082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbach VJ, Kaplan BH, Fredman L, Kleinbaum DG. Social ties and mortality in Evans County, Georgia. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;123:577–591. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Kaplan GA, Knudsen L, Cohen R, Guralnik J. Social network ties and mortality among tile elderly in the Alameda County Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;126:714–723. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Berkman LF. Structural characteristics of social networks and their relationship with social support in the elderly: Who provides support. Social science & medicine. 1988;26:737–749. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Berkman LF, Kohout F, Lacroix A, Glynn R, Blazer D. Intercommunity variations in the association between social ties and mortality in the elderly: A comparative analysis of three communities. Annals of Epidemiology. 1993;3:325–335. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90058-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE. Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration. Annals of Epidemiology. 1996;6:442–451. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena-Rivera J. Extended kinship in the United States: Competing models and the case of la familia Chicana. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1979;41:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Shor E, Roelfs DJ, Yogev T. The strength of family ties: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of self-reported social support and mortality. Social Networks. 2013;35:626–638. [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Hill DR. Gender differences in social support and physical health. Health psychology. 1991;10:102–111. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shye D, Mullooly JP, Freeborn DK, Pope CR. Gender differences in the relationship between social network support and mortality: A longitudinal study of an elderly cohort. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;41:935–947. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00404-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PA. Trajectories of social engagement and mortality in late life. Journal of Aging and Health. 2012;24:547–568. doi: 10.1177/0898264311432310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. Social support & physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1987;28:306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health a flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annual Review of Sociology. 2010;36:139–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaux A. Variations in social support associated with gender, ethnicity, and age. Journal of Social Issues. 1985;41:89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B. The meaning of social support and the mediation of stress across cultures. In: Vega W, Miranda M, editors. Stress & Hispanic mental health: Relating research to service delivery. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1985. pp. 48–75. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA. Hispanic families in the 1980s: A decade of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:1015–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Walen HR, Lachman ME. Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2000;17:5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins K. Social support and mortality in seniors. Health reports. 2003;14:21–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]