Abstract

Introduction

Obesity, type 2 diabetes and dental caries are all major public health problems in the UK, with significant costs to the healthcare service. We aim to conduct a systematic review to summarise the evidence on the effectiveness of product reformulation measures to reduce the sugar content of food and drink on the population's sugar consumption and health.

Methods and analysis

Electronic database will be systematically searched using a combination of terms, tailored to optimise sensitivity, specificity, and the syntax and functionality of each database. The databases searched will include the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE (Ovid) and Scopus. The bibliographies of those papers that match inclusion criteria will be searched by hand to identify any further, relevant references, which will be subject to the same screening and selection process. The database search results will be supplemented by hand searches. In addition to the peer-reviewed literature, a number of grey literature searches will be undertaken using the broad search terms ‘sugar’ and ‘food’ or ‘drink’ and ‘reduction’, these searches will include key government and organisation websites as well as general searches in Google. The selection of the studies, data collection and quality appraisal will be performed independently by 2 reviewers. Data will be initially analysed through a narrative synthesis method. If a subset of data we analyse appears comparable, we will investigate the possibility of performing a meta-analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval will not be required as this is a protocol for a systematic review. The findings will be disseminated widely through conference presentations and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016034022.

Keywords: sugar, reduction, obesity, type 2 diabetes, tooth decay

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review is the first to explore sugar reduction through reformulation and its effect on consumption and health.

Summarising the evidence on sugar reduction through reformulation will provide new insights into the approaches tested thus far and will help inform research and policy agenda.

Studies with high heterogeneity and varying quality may limit the quality of evidence for this systematic review.

Introduction

Obesity, type 2 diabetes and dental caries are all major public health problems in the UK,1–7 with significant costs to the healthcare service.8 It is recognised that excessive consumption of free sugars (sugar), particularly in the form of sugar-sweetened drinks, is associated with these conditions.9–19

‘Free sugars’ include all monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, plus sugars naturally present in honey, syrups and unsweetened fruit juices. Under this definition lactose (milk sugars) when naturally present in milk and milk products and sugars contained within the cellular structure of foods (particularly fruits and vegetables) are excluded.

In July 2015, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) recommended that in the UK, average intake of free sugars should not exceed 5% of total energy intake (19 g for children aged 4–6, 24 g for children aged 7–10 and 30 g for adults).20 This is in line with the WHO's new conditional guideline on free sugars intake.21 22 Furthermore, SACN advised that consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks should be minimised in children and adults.20 By meeting the recommendations within 10 years, it would not only improve an individual’s quality of life but also could save the National Health Service (NHS), based on a conservative assessment, around £500 million every year.23

Current average intakes of free sugars (expressed from non-milk extrinsic sugars in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey) exceed recommendations in all age groups. The average sugars intake in adults was 59 g per day which is the equivalent to 236 calories and contributes to 12.1% of energy intake, which exceeds the current recommendation (<5% of energy intake). Children have a higher sugars intake. The average sugars intake was 60.8 and 74.2 g per day in 4–10 and 11–18 years old, respectively.24 This is likely to be an underestimate of how much free sugars are consumed25 because under-reporting is highly prevalent in these types of surveys.26–29 Additionally, consumers are largely unaware of the amount of free sugars in products they regularly buy because only total sugars are labelled on product packaging in most countries with nutrition labelling.

In the UK, a group of academics behind the UK's Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH) campaign launched Action on Sugar in January 2014, with the aim of reducing free sugars intake in the UK by following the same model as the successful UK salt reduction strategy.30 31 The average salt intake for adults fell from 9.5 g in 2000–2001 to 8.1 g in 2011 accompanied by a significant fall in population blood pressure and mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease.32 33 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence estimated that this prevented around 18 000 strokes and heart attacks, and saved around £1.5 billion in healthcare costs per year in the UK.34

The key to the success of the UK salt reduction programme is setting incremental targets for each food group with a specified timeframe to be achieved using maximum and average or sales-weighted average targets.30 Since there has been a gradual, progressive reduction in salt, the UK population has adjusted to the taste of lower salt concentrations. There has been no loss of sales or switching between products as a result of salt reduction, or addition of salt at the table. As this policy targets all foods, and does not rely on consumer behaviour changes, it particularly benefits people from lower income households who consume more unhealthy diets than people in higher income households.35

Given the progress made with the salt reduction programme in the UK, it has been proposed that free sugars can be reduced through a similar systematic, unobtrusive and gradual reformulation programme for manufacturers. This would be achieved by setting progressive targets for each food and drink category, which would allow for an incremental reduction of free sugars and provide a level playing field to industry, which is vital for a voluntary policy. However, a major difference to salt reformulation is that the sugar content contribute to the weight or volume of the product (although not in liquids). Therefore, a reduction in sugar content in solid products can be achieved by reducing the portion size, although this does not mean people will necessarily eat less overall. However, it is possible to substitute sugars with polyols or insoluble fibres that are not metabolised or absorbed. Liquid products can have the sugar reduced without affecting the volume, for example, sugar-sweetened drinks. Reformulation is likely to become a priority in the UK since it was recommended by Public Health England to the UK government.23

While companies have created lower sugar and calorie variants,36 37 there is still little known about the potential impact of reformulation on sugar intake and health outcomes. Therefore, the aim of this review is to examine the evidence on the effectiveness of product reformulation measures to reduce the sugar content of food and drink on the population's sugar consumption and health.

Methods and analysis

Given it is likely there is major heterogeneity in the type of studies that may be included in this systematic review. A broader more flexible approach will be required to construct a review that remains fit for purpose while utilising a systematic methodology.

This protocol adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement.38

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Inclusion criteria

Population: studies involving populations of any age.

Type of outcome measures:

Consumption patterns (sugar intake);

Health outcomes (body weight, dental health, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk).

Type of interventions: Any studies investigating the effectiveness of product reformulation measures to reduce the population's sugar consumption and improve health outcome.

Type of studies: Both quantitative and qualitative research designs will be included in the review. Also, commentaries, editorials, reviews or discussion pieces that focused on reformulation will also be included. Studies will not be selected on methodological quality. However, the number of excluded studies (including reasons for exclusion for those excluded following review of the full text) will be recorded at each stage. Searches will be conducted from 1990 onwards. This is because publications about reformulation, particularly salt reformulation, began to appear in the literature in the early 2000, so setting the search from 1990 will guarantee the capture of any publications published pre-2000.

Exclusion criteria

Non-English language studies and papers

Studies published outside of stipulated publication dates

Studies with no relevant outcome measures.

Search strategy

Electronic database will be systematically searched using a combination of terms, tailored to optimise sensitivity, specificity, and the syntax and functionality of each database (draft search in online supplementary file 1). The databases searched will include the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE (Ovid) and Scopus. The bibliographies of those papers that match inclusion criteria will be searched by hand to identify any further, relevant references, which will be subject to the same screening and selection process. The database search results will be supplemented by hand searches.

bmjopen-2016-011052supp1.pdf (172.7KB, pdf)

In addition to the peer-reviewed literature, a number of grey literature searches will be undertaken using the broad search terms ‘sugar’ and ‘food’ or ‘drink’ and ‘reduction’, these searches will include key government and organisation websites as well as general searches in Google. Despite being named ‘grey literature’, they are an important source of information. Indeed, they may provide more useful information in some areas, such as ours.

Screening and data extraction

All papers identified from the initial electronic search process will be imported into an Endnote library and duplicates will be removed. The eligibility criteria will be applied to the results and all identified references screened independently by two reviewers (KMH and FJH) using a two-stage approach. First stage involves reviewing the title and abstract. Second stage will extract and assess the full text versions of the shortlisted papers. GAM will be consulted where any question or ambiguity arise. A standardised data extraction form will be finalised (see online supplementary file 2). The data extraction form will be piloted prior to its use. Data to be extracted will include authors, year of publication, country, study design, participant characteristics, description of the intervention and study findings.

bmjopen-2016-011052supp2.pdf (286.3KB, pdf)

Quality assessment

Quality appraisals will be carried out for each included study using the Joanna Briggs Institute appraisal tools.39 All data will be extracted and quality assured by two reviewers.

Data synthesis and analysis

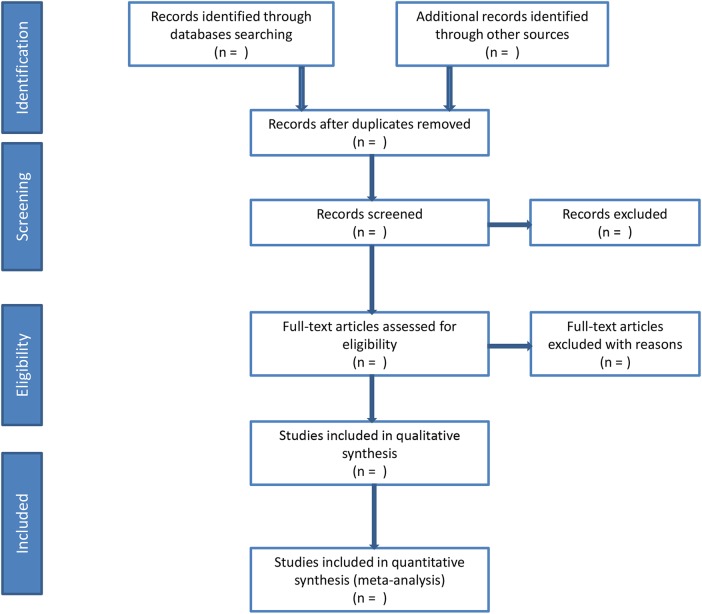

The PRISMA flow chart38 will be used to document the number of studies identified during the search process and those excluded and included according to the outlined eligibility criteria (figure 1). The data will be initially analysed through a narrative synthesis method. The availability of appropriate data and resources to conduct a meta-analysis will be considered, where feasible.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic review.

Gaps and limitations

There are a few gaps and limitations that we want to acknowledge in anticipation of the findings of the systematic review. First, the average sugars intake reported in dietary surveys in adults is likely to be an underestimate of how much free sugars are consumed25 because under-reporting is highly prevalent.26–29 Therefore, any studies of associations with health based on self-reported data may potentially underestimate the effect of reformulation but also underestimate the scale of the policy responses necessary to deal with excessive free sugars intake. Second, free sugars exclude other sugars such as lactose and intrinsic sugars in fruit and vegetables. However, there is no current test that distinguishes these types of sugars and neither does the current labelling requirements for ‘total sugars’. One implication of this is that it is difficult to determine the extent of reformulation in dairy products such as yogurts and milkshakes and in products that contain substantial amounts of fruit and vegetables. This can add a layer of complication when estimating effect of reformulation. Also, this can act as a disincentive to manufacturers to attempt sugar reformulation when their efforts at reduction can be confounded by the presence of milk, fruit and vegetables.

Implications

This systematic review aims to summarise the evidence on the effectiveness of product reformulation measures to reduce the sugar content of food and drink on the population's sugar consumption and health. Results of this systematic review will therefore provide new insights into the approaches tested thus far. The systematic review may also identify specific gaps in the evidence, which would inform agenda for future research and policy.

Amendments

If we need to amend this protocol, the date, rationale and a description of each protocol change will be reported.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval will not be required as this is a protocol for a systematic review. This systematic review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal. It will be disseminated electronically and in print.

Footnotes

Contributors: KMH conceived the idea and designed protocol; FJH and GAM critically appraised the protocol.

Competing interests: KMH is employee of Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH), a non-profit charitable organisation. FJH is a member of CASH and its international branch World Action on Salt & Health (WASH) and does not receive any financial support from CASH or WASH. GAM is Chairman of Blood Pressure UK (BPUK), Chairman of CASH, Chairman of WASH and Chairman of Action on Sugar. BPUK, CASH, WASH and Action on Sugar are non-profit charitable organisations.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: For further information please contact Kawther Hashem k.hashem@qmul.ac.uk.

References

- 1.HSCIC. National Diabetes Audit 2008. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB02580/nati-diab-audi-07-08-exec-summ.pdf (accessed Jul 2015).

- 2.HSCIC. Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet: England 2014 2014. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB13648/Obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2014-rep.pdf (accessed July 2015).

- 3.NHS. Executive Summary: Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB01086/adul-dent-heal-surv-summ-them-exec-2009-rep2.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 4.PHE. National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: oral health survey of five-year-old children 2012. A report on the prevalence and severity of dental decay 2012. http://www.nwph.net/dentalhealth/Oral%20Health%205yr%20old%20children%202012%20final%20report%20gateway%20approved.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 5.PHE. UK and Ireland prevalence and trends 2013. https://www.noo.org.uk/NOO_about_obesity/adult_obesity/UK_prevalence_and_trends (accessed 2 Jul 2015).

- 6.PHE. Dental public health epidemiology programme. Oral health survey of three-year-old children 2013. A report on the prevalence and severity of dental decay 2014. http://www.nwph.net/dentalhealth/reports/DPHEP%20for%20England%20OH%20Survey%203yr%202013%20Report.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 7.PHE. Adult obesity and type 2 diabetes 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/338934/Adult_obesity_and_type_2_diabetes_.pdf (accessed 2 Jul 2015).

- 8.PHE. Sugar reduction Responding to the challenge 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/324043/Sugar_Reduction_Responding_to_the_Challenge_26_June.pdf (accessed 1 Jun 2014).

- 9.SACN. Draft Carbohydrates and Health report Scientific consultation: 26 June to 1 September 2014 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/339771/Draft_SACN_Carbohydrates_and_Health_report_consultation.pdf (accessed 1 Dec 2015).

- 10.Romaguera D, Norat T, Wark PA et al. . Consumption of sweet beverages and type 2 diabetes incidence in European adults: results from EPIC-InterAct. Diabetologia 2013;56:1520–30. 10.1007/s00125-013-2899-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Koning L, Malik VS, Rimm EB et al. . Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverage consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:1321–7. 10.3945/ajcn.110.007922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maki KC, Phillips AK. Dietary substitutions for refined carbohydrate that show promise for reducing risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. J Nutr 2015;145:159S–63S. 10.3945/jn.114.195149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A et al. . Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: critical review and evidence base. Nutrition 2015;31:1–13. 10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 2013;346:e7492 10.1136/bmj.e7492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M et al. . Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009;120:1011–20. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xi B, Li SS, Liu ZL et al. . Intake of fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e93471 10.1371/journal.pone.0093471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 2007;97:667–75. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattes R. Fluid calories and energy balance: the good, the bad, and the uncertain. Physiol Behav 2006;89:66–70. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiMeglio DP, Mattes RD. Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: effects on food intake and body weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:794–800. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.PHE. Why 5%? 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/446010/Why_5__-_The_Science_Behind_SACN.pdf (accessed July 2015).

- 21.WHO. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/149782/1/9789241549028_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 1 Jul 2015).

- 22.Moynihan PJ, Kelly SA. Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J Dent Res 2014;93:8–18. 10.1177/0022034513508954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PHE. Sugar Reduction The evidence for action 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/470179/Sugar_reduction_The_evidence_for_action.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).

- 24.PHE. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: results from Years 1 to 4 (combined) of the rolling programme for 2008 and 2009 to 2011 and 2012 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-results-from-years-1-to-4-combined-of-the-rolling-programme-for-2008-and-2009-to-2011-and-2012 (accessed 2 Jun 2014).

- 25.Rennie KL, Jebb SA, Wright A et al. . Secular trends in under-reporting in young people. Br J Nutr 2005;93:241–7. 10.1079/BJN20041307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hebert JR, Ebbeling CB, Matthews CE et al. . Systematic errors in middle-aged women's estimates of energy intake: comparing three self-report measures to total energy expenditure from doubly labeled water. Ann Epidemiol 2002;12:577–86. 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00297-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lara JJ, Scott JA, Lean MEJ. Intentional mis-reporting of food consumption and its relationship with body mass index and psychological scores in women. J Hum Nutr Diet 2004;17:209–18. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2004.00520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rennie KL, Coward A, Jebb SA. Estimating under-reporting of energy intake in dietary surveys using an individualised method. Br J Nutr 2007;97:1169–76. 10.1017/S0007114507433086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Archer E, Hand GA, Blair SN. Correction: validity of U.S. nutritional surveillance: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey caloric energy intake data, 1971–2010. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e76632 10.1371/journal.pone.0076632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He FJ, Brinsden HC, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: a successful experiment in public health. J Hum Hypertens 2014;28:345–52. 10.1038/jhh.2013.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macgregor GA, Hashem KM. Action on sugar—lessons from UK salt reduction programme. Lancet 2014;383:929–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60200-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DoH. Department of Health: Assessment of Dietary Sodium Levels Among Adults (aged 19-64) in England, 2011 2011. http://transparency.dh.gov.uk/2012/06/21/sodium-levels-among-adults/ (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 33.He FJ, Pombo-Rodrigues S, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004549 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NICE. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guidance on the prevention of cardiovascular disease at the population level 2010. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PH25 (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 35.FSA. Low income diet and nutrition survey. Summary of key findings 2007. http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/lidnssummary.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 36.The-Grocer. Low-sugar Coca-Cola Life hits spot with Pepsi Max drinkers. 2014; 237(8186) (accessed 1 Dec 2015).

- 37.Arthur R. Reformulation on a mass scale? Sugar, stevia, sweeteners: the sticky question of a soft drink shake up 2015. http://www.beveragedaily.com/Markets/Coca-Cola-Sprite-Euromonitor-sugar-calories-Pepsi (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

- 38.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.JBI. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2014 2014. http://www.joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual_Mixed-Methods-Review-Methods-2014-ch1.pdf (accessed 2 Dec 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011052supp1.pdf (172.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-011052supp2.pdf (286.3KB, pdf)