Abstract

Polymorphisms in the rifampin resistance mutation frequency (f) were studied in 696 Escherichia coli strains from Spain, Sweden, and Denmark. Of the 696 strains, 23% were weakly hypermutable (4 × 10−8 ≤ f < 4 × 10−7), and 0.7% were strongly hypermutable (f ≥ 4 × 10−7). Weak mutators were apparently more frequent in southern Europe and in blood isolates (38%) than in urinary tract isolates (25%) and feces of healthy volunteers (11%).

Microbial evolution is dependent on two opposing forces, the maintenance of genetic information and the generation of some suitable level of genetic variation on which selection can act. In most cases, genetic variation is assured by errors in DNA replication, determined by the accuracy of DNA polymerases and various DNA repair systems. Particular environmental characteristics will influence selection of the optimal amount of genetic variation for a given organism with a specific population structure. If the environment changes rapidly in time or is heterogeneous, variants with increased mutation rates will tend to be selected, since they have an increased probability of forming beneficial mutations. Conversely, if the environment is constant, as the organism becomes maximally adapted, mutation rates tend to decrease because of the costs associated with deleterious mutations (4, 6, 7). These considerations suggest that environment-dependent polymorphisms in mutation frequency can be expected in nature.

Mutation frequencies were determined in a collection of 696 Escherichia coli strains obtained from 2000 to 2003. Of the 696 E. coli strains, 300 were from Spain (100 from positive urine cultures, 100 from blood cultures, and 100 from the stools of young healthy volunteers), 170 were from Denmark (blood cultures), and 226 were from Sweden (urinary tract cultures from outpatients). Each Luria-Bertani (LB) tube was inoculated with an independent colony obtained from a blood agar plate; three LB tubes were used. After 24 h of incubation, appropriate dilutions were seeded onto LB agar plates and LB agar plates containing rifampin (100 μg/ml), and colony counts were performed after 24 or 48 h, respectively. Mutation frequencies are reported as a proportion of the number of rifampin-resistant colonies to the total viable count. The results corresponded to the mean value obtained in three independent experiments that were repeated in cases of suspected jackpots.

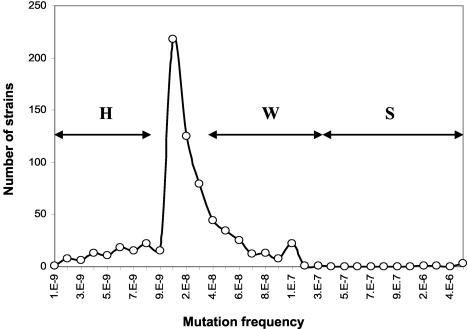

Categories were established considering the distribution of frequencies of the 696 E. coli strains (Fig. 1). A strain was considered normomutable when the mutation frequency (f) was at or close to the modal point of the distribution of mutation frequencies; for practical purposes, it was established as 8 × 10−9 < f < 4 × 10−8. Strains were considered weak mutators if their frequency was 4 × 10−8 ≤ f < 4 × 10−7 and strong mutators if f ≥ 4 × 10−7. Hypomutable strains were defined as strains with f ≤ 8 × 10−9.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of rifampin resistance mutation frequencies of 696 E. coli strains isolated from patients and healthy volunteers from Spain, Sweden, and Denmark. The horizontal arrows show the frequency ranges defining hypomutable strains (H), weakly hypermutable strains (W), and strongly hypermutable strains (S). The peak in the distribution corresponds to the normomutable strains. 1.E-9, 1.0 × 10−9.

A sharp peak in the frequency distribution was always found at 10−8. From this value, a few strains had lower mutation frequencies, down to 10−9. To the right of the modal peak, an unexpectedly high number of strains (23%) show moderately increased mutation frequencies. All five strong mutators detected in the collection of 696 strains (0.7%) had rifampin resistance mutation frequencies greater than 10−6. Luria-Delbrück fluctuation tests (5, 8) were performed with a sample of 12 strains each from the three different mutation frequency classes, and the differences between the mutation rates of the strains were fully confirmed. Differences in the proportions of the different categories were statistically evaluated by using the Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn, and Mann-Whitney tests.

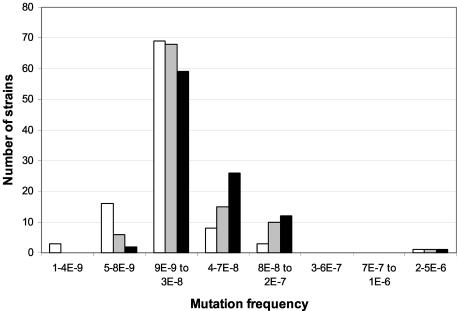

In the collection of 300 E. coli isolates from Spain (Fig. 2), the main peak of normomutable strains accounted for 59% of the strains from blood cultures, 68% of the strains from urine samples, and 69% of the fecal strains from healthy volunteers. For the same three groups, weak mutators represented 38, 25, and 11% of the strains, respectively. Differences were statistically significant between blood and urine samples from healthy volunteers (P < 0.001) and between blood and urine samples in general (P = 0.03). We found only one strong mutator strain in three collections of clinical isolates (1% in the whole series). Hypomutable strains were isolated in significantly higher proportions in the E. coli isolates from healthy volunteers (19%) than from strains from blood cultures and urinary tract infections (6 and 2%, respectively) (P < 0.001).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of rifampin resistance mutation frequencies of 300 Spanish E. coli isolates according to the isolate origin: feces from healthy volunteers (100 isolates) (white bars), urinary tract infections (100 isolates) (shaded bars), and blood cultures (100 isolates) (black bars). 1-4E-9, 1 × 10−9 to 4 × 10−9.

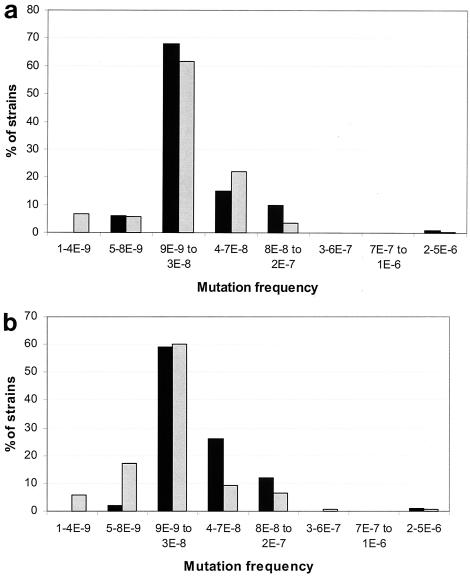

In the series of 226 E. coli strains isolated from positive urine cultures from patients in Sweden, 62% of the strains were normomutable and 26% were weak mutators (Fig. 3a). The distribution of Swedish isolates was similar to that of the Spanish isolates, but Spanish weak mutators tended to have higher frequencies of mutation than the Swedish ones. Finally, 12% of the strains were hypomutable. Only one strong-mutator strain (0.4%) was detected.

FIG. 3.

(a) Distribution of rifampin resistance mutation frequencies of uropathogenic E. coli isolates from 226 Swedish (shaded) and 100 Spanish (black) patients. (b) Distribution of E. coli mutation frequencies of bacteremic isolates from 170 Danish (shaded) and 100 Spanish (black) patients. 1-4E-9, 1 × 10−9 to 4 × 10−9.

In the collection of 170 E. coli strains from bacteremic patients in Denmark (Fig. 3b), 60% of the strains were in the normomutable category, but 23% were hypomutable strains. Sixteen percent of the strains were weak-mutator strains, and only one strong-mutator isolate (0.6%) was detected. The proportion of weak mutators among Danish blood isolates was significantly lower than that found in Spanish blood isolates (P < 0.001).

These data indicate that there may be geographical differences in the E. coli mutation frequency distribution profile, but differences due to different types of hospitals cannot be ruled out. How important antibiotic therapy is in selecting hypermutable E. coli remains an open question. No correlation between mutation rates and antibiotic resistance has been shown in uropathogenic E. coli strains (3). Nevertheless, it has been shown that in E. coli, strains with increased mutation rates correlate with strains showing high-level ciprofloxacin resistance (9). We tested ciprofloxacin (E-test; AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) using a resistance breakpoint of 1 μg/ml (15) in the series of urinary tract pathogens from patients in Sweden: 15% of hypermutable strains were ciprofloxacin resistant, a proportion slightly higher but not significantly different from the 12% proportion of the entire collection.

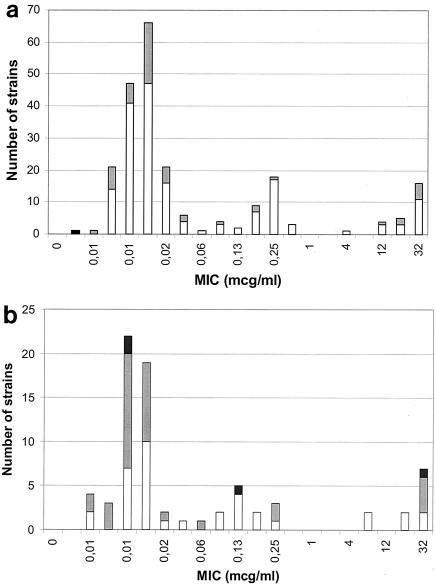

As shown in Fig. 4, hypermutable strains (23% of the total) are almost evenly distributed along the full range of MICs. We studied ciprofloxacin resistance in a second series of 75 Spanish strains with a higher proportion (52%) of hypermutable strains, including all four strong mutators. Supporting the first observation, the overall rate of ciprofloxacin resistance was 15%, and the rate of ciprofloxacin resistance for hypermutable strains was 13%, with the distribution of hypermutable strains along the MIC range similar to that of the Swedish strains (Fig. 4). Thus, we were unable to find any significant association in our strains between a mutator phenotype and ciprofloxacin resistance in countries with a low (Sweden) or high (Spain) prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance. Similar results were obtained with nalidixic acid (data not shown). We might suggest that for E. coli of community origin, fluoroquinolone resistance frequently arises and evolves among nonhypermutable strains, but in hospitals, clones under continued antibiotic challenges could favor hypermutators (11, 13, 14, 16, 18).

FIG. 4.

Distribution of normomutable (white), weakly hypermutable (shaded), and strongly hypermutable (black) E. coli strains among isolates inhibited by different ciprofloxacin concentrations. (a) Distribution of the 226 uropathogenic E. coli strains isolated from Swedish patients. (b) Distribution of 75 E. coli strains with an enriched proportion of hypermutable strains isolated from Spanish patients.

The frequency of strong mutators in our series roughly corresponds to what was found in previous series, around 1% (10). Less attention has been paid in the literature to weak mutators. Using our categorization criteria, we found that the proportion of weak mutators is around 25% in the series of strains from France (12). These proportions are far higher than the proportions that could be expected by random mutation of the genes that stringently maintain the normal mutation frequency. As hypermutability is not an advantage by itself, the abundance of strains with increased mutation frequency ought to be maintained by positive selection (17). In dense populations, as in the case of E. coli, advantageous mutations will tend to appear in weak mutators, and selection will therefore enrich low mutating organisms. The success of weak mutators may prevent further fixation of strong mutators (2).

Hospital-based and pathogenic (blood cultures) strains have a higher exposure to antibiotic or host-to-host transmission challenges than commensal community-based organisms. Similar arguments based on more frequent host-to-host or host-environment transmission (sociology and climate), and/or higher antibiotic consumption (1) could be applied to explain differences in different geographical location, emphasizing the importance of local biology in the mechanisms involved in E. coli evolution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant QLK2-CT-2001-873 from the European Commission.

We thank R. Cantón, E. Loza, R. del Campo, and T. Coque for providing strains from Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cars, O., S. Molstad, and A. Melander. 2001. Variation in antibiotic use in the European Union. Lancet 357:1851-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao, L., and E. C. Cox. 1983. Competition between high and low mutating strains of Escherichia coli. Evolution 37:125-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denamur, E., S. Bonacorsi, A. Giraud, P. Duriez, F. Hilali, C. Amorin, E. Bingen, A. Andremont, B. Picard, F. Taddei, and I. Matic. 2002. High frequency of mutator strains among human uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. J. Bacteriol. 184:605-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVisser, J. A. 2002. The fate of microbial mutators. Microbiology 148:1247-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake, J. W., B. Charlesworth, D. Charlesworth, and J. F. Crow. 1998. Rates of spontaneous mutation. Genetics 148:1667-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funchain, P., A. Yeung, J. L. Stewart, R. Lin, M. M. Slupska, and J. H. Miller. 2000. The consequences of growth of a mutator strain of Escherichia coli as measured by loss of function among multiple gene targets and loss of fitness. Genetics 154:959-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giraud, A., I. Matic, O. Tenaillon, A. Clara, M. Radman, M. Fons, and F. Taddei. 2001. Costs and benefits of high mutation rates: adaptive evolution of bacteria in the mouse gut. Science 291:2606-2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones, M. E., S. M. Thomas, and A. Rogers. 1994. Luria-Delbruck fluctuation experiments: design and analysis. Genetics 136:1209-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komp Lindgren, P., A. Karlsson, and D. Hughes. 2003. Mutation rate and evolution of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3222-3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeClerc, J. E., B. Li, W. L. Payne, and T. A. Cebula. 1996. High mutation frequencies among Escherichia coli and Salmonella pathogens. Science 274:1208-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez, J. L., and F. Baquero. 2002. Interactions among strategies associated with bacterial infection: pathogenicity, epidemicity, and antibiotic resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:647-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matic, I., M. Radman, F. Taddei, B. Picard, C. Doit, E. Bingen, E. Denamur, and J. Elion. 1997. Highly variable mutation rates in commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 277:1833-1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller, K., A. J. O'Neill, and I. Chopra. 2002. Response of Escherichia coli hypermutators to selection pressure with antimicrobial agents from different classes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:925-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller, K., A. J. O'Neill, and I. Chopra. 2004. Escherichia coli mutators present an enhanced risk for emergence of antibiotic resistance during urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:23-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 13th informational supplement. M100-S13. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 16.Oliver, A., R. Cantón, P. Campo, F. Baquero, and J. Blázquez. 2000. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288:1251-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaver, A. C., P. G. Dombrowski, J. Y. Sweeney, T. Treis, R. M. Zappala, and P. D. Sniegowski. 2002. Fitness evolution and the rise of mutator alleles in experimental Escherichia coli populations. Genetics 162:557-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka, M. M., C. T. Bergstrom, and B. R. Levin. 2003. The evolution of mutator genes in bacterial populations: the roles of environmental change and timing. Genetics 164:843-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]