Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease and dementia share a number of risk factors including hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking, obesity, diabetes and physical inactivity. The rise of eHealth has led to increasing opportunities for large-scale delivery of prevention programmes encouraging self-management. The aim of this study is to investigate whether a multidomain intervention to optimise self-management of cardiovascular risk factors in older individuals, delivered through an coach-supported interactive internet platform, can improve the cardiovascular risk profile and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline.

Methods and analysis

HATICE is a multinational, multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label blinded end point (PROBE) trial with 18 months intervention. Recruitment of 2600 older people (≥65 years) at increased risk of cardiovascular disease will take place in the Netherlands, Finland and France. Participants randomised to the intervention condition will have access to an interactive internet platform, stimulating self-management of vascular risk factors, with remote support by a coach. Participants in the control group will have access to a static internet platform with basic health information.

The primary outcome is a composite score based on the average z-score of the difference between baseline and 18 months follow-up values of systolic blood pressure, low-density-lipoprotein and body mass index. Main secondary outcomes include the effect on the individual components of the primary outcome, the effect on lifestyle-related risk factors, incident cardiovascular disease, mortality, cognitive functioning, mood and cost-effectiveness.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Ouest et Outre Mer in France and the Northern Savo Hospital District Research Ethics Committee in Finland.

We expect that data from this study will result in a manuscript published in a peer-reviewed clinical open access journal.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN48151589.

Keywords: PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH, CARDIOLOGY, NEUROLOGY, EHEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study proposes the assessment of a pragmatic, easily implementable, coach-supported interactive internet platform for the improvement of the cardiovascular risk profile.

The strengths of the study include the large sample size, the multinational recruitment and cooperation and the relatively less investigated older target population.

Limitations include the relatively short follow-up.

Background

Despite impressive reductions of its incidence in many countries, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) continue to be a major public health issue with over 4 million deaths in Europe each year.1 In parallel, the global prevalence of dementia is likely to increase in the coming years, mainly due to increased life expectancy.2 CVD and dementia share a number of risk factors including hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking, diabetes, obesity and physical inactivity.3 4 Treatments targeting most of these risk factors are effective for the prevention of CVD.5–7 Even small improvements of vascular risk factor management in a large population, can lead to a large effect on incident cardiovascular disease at the population level8 and substantial reductions in healthcare costs.9

Although up to 30% of dementia cases are attributable to modifiable (mostly cardiovascular) risk factors,10 there is currently insufficient evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that treatment will also reduce dementia incidence. Vascular risk factors rarely occur in isolation. It is plausible that targeting multiple risk factors simultaneously can have an additive effect on the reduction of the risk of CVD and dementia, but RCTs targeting the older population are rare and with mixed results.11–13 However, the recently published large RCT ‘Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER)’, suggest that a multidomain lifestyle intervention could improve or maintain cognitive functioning in at-risk elderly people from the general population.14

In spite of clear guidelines for cardiovascular risk management mainly for younger adults,15 but also applied on older adults, the sobering reality of daily practice is that target values are often not reached,16 17 leaving room for a substantial improvement. Both patient and doctor factors play a role in this gap between evidence and practice.18 Innovative strategies to improve cardiovascular risk management are therefore urgently needed.

Patient self-management is a potentially powerful strategy to improve adherence to therapy in CVD risk reduction.19 20 Specific patient characteristics can determine the strategies applied at the individual level. Increasing knowledge about a healthy lifestyle and the possibility for tailor-made prevention programmes can empower individuals and improve adherence with pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.21

When designing a trial on prevention of cardiovascular disease and dementia, the optimal age-range of the target population is matter of debate. The benefits of higher efficacy in midlife are counteracted by the large sample size and long follow-up required to detect an effect on incident disease.22 The optimal time-window depends on the peak incidence age, and is probably somewhere in late midlife or early late-life.23

The internet has become a major source of information for people of all ages, and its use among older people throughout Europe has increased dramatically, making it a potentially suitable medium for the delivery of widely implementable healthcare interventions.24 Together with the rise of eHealth this creates opportunities for large-scale delivery of prevention programmes encouraging self-management.25

In the Healthy Ageing Through Internet Counselling in the Elderly (HATICE) trial we investigate whether a coach-supported interactive internet intervention to optimise self-management of cardiovascular risk factors in older individuals can improve the cardiovascular risk profile and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline.

Methods

Study design

HATICE is a pragmatic, multinational, multicentre, investigator initiated, prospective, randomised, open-label blinded end point (PROBE),26 trial with 18 months intervention and follow-up. Owing to the nature of the intervention, complete double blinding is not possible. Investigators evaluating outcome measures are blinded for the randomisation group and the primary outcome is based on objective parameters.

Study population and recruitment

The study population will consist of community-dwelling people aged 65 years or older who have two or more cardiovascular risk factors and/or manifest cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus. This leads to a mixed population with an indication for either primary or secondary prevention. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; GP, general practitioner; LDL, low-density-lipoprotein; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Recruitment takes place in the Netherlands, Finland and France. Based on a pilot study (later described) and experience from previous trials14 27 28 we expect a response rate of ∼10%. In the Netherlands recruitment will take place through registration lists of all individuals ≥65 years registered in primary care practices. In Finland recruitment will take place by inviting individuals from the population registry based on age, by selecting participants from previous population-based surveys, as was previously carried out to recruit for RCTs,29 and by advertisements in local media, patient organisations and their websites and healthcare centres. In France participants will be enrolled from various sources. In addition to recruitment through general practitioners (GP), prevention centres, cardiovascular risk factors consultations and the geriatrics department and memory clinics in the Toulouse area, participants will also be recruited through mailing lists and advertisements in local media, seniors clubs and conferences.

People aged ≥65 years will receive an information letter and are invited to apply through a country specific website or emailing or calling the local study centre. Those interested will receive a prescreening telephone call. If eligible, people are invited to attend the first screening visit.

Recruitment started in March 2015.

Intervention

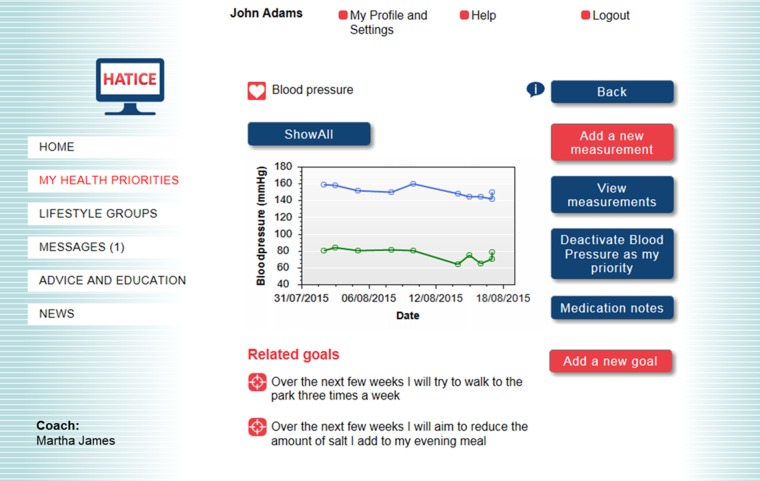

Participants randomised to the intervention condition will have access to an interactive internet platform, specifically designed for use by older people (figure 1). The platform is in the participants own language (Finnish, French or Dutch) and facilitates self-management of vascular and lifestyle-related risk factors, including blood pressure, overweight, physical inactivity, diet, smoking, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia. After secure login, a participant can view his/her own cardiovascular risk profile created through baseline measurements. At the interactive part of the platform, the participants can set a personal goal for lifestyle change, make a corresponding action plan, monitor goals by entering data (eg, blood pressure or a food diary), join lifestyle activity groups and correspond with their coach, whom they have met in person at the baseline assessment. In addition, participants can find health information in static and interactive education-modules, watch peer videos on lifestyle change, and use a programme for cognitive training.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of intervention portal (simulated values, participant and coach).

The platform and the guidance provided by the coach are based on current European and national guidelines for cardiovascular risk management.15 When indicated, this is adapted to national guidelines from one of the three countries where participants are recruited. Owing to the heterogeneous population in this trial, which includes participants with elevated cardiovascular risk with or without established CVD, primary as well as secondary prevention guidelines will be applied. The HATICE intervention platform does not replace existing healthcare in any way, but is offered as an add-on.

The platform is supported by a coach trained in motivational interviewing. All coaches in all three countries work according to a coach protocol set up by the research team. Guided by the preferences of the participant, the coach provides remote support by assisting in realistic goal-setting according to the ‘specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and time bound (SMART) principle.30 Communication between the participant and the coach is through a messaging system within the platform. The coach receives automatic alerts when participants enter measurements or when a participant has not been active on the platform for more than 3 weeks. The coach advises the participant to log in at least once a week, but this is not compulsory.

There are regular national and international meetings with the coaches and the research team to discuss the intervention and to solve discrepancies between countries and coaches.

Participants randomised to the control condition will have access to an internet platform with only the static information on cardiovascular risk factors, but lacking interactive features and the support of a coach.

Pilot

Between September 2014 and February 2015 a pilot study was conducted in the three participating countries with a total of 41 participants, in order to test the trial procedure and the platform. We adjusted the protocol and the platform where needed, according to the feedback of the end users; for example, enlargement of electronic buttons, more guidance on the use of the platform (eg, introduction video and more instructions from the coach) and more positive tone of voice (eg, ‘health factor’ instead of ‘risk factor’).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is a composite score based on the average z-score of the difference between baseline and 18 months follow-up values of systolic blood pressure, low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) and body mass index (BMI). Several considerations have led to the decision for this outcome. First, a multidomain outcome capturing the potential effect of our multidomain intervention on a composite of risk factors was deemed appropriate. Second, no existing cardiovascular risk score can be applied to both primary and secondary prevention, whereas our pragmatic trial targets a mixed population with an indication for primary or secondary prevention. Third, we deemed it inappropriate to include any parameter based on patient-reported measures (eg, physical activity questionnaire) in our primary outcome due to the risk of reporting bias; self-reported parameters were considered insufficiently reliable for the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Main secondary outcomes include the difference between baseline and month 18 on the individual components of the primary outcome, the difference in lifestyle-related risk factors (physical exercise, diet, smoking status), the difference in estimated 10-year cardiovascular disease risk based on the Framingham cardiovascular disease risk score (measured at 18 months), cardiovascular risk factors, aging and dementia risk-score(CAIDE),31 incident cardiovascular disease, mortality, disability, cognitive functioning, incident dementia, physical fitness, mood and cost-effectiveness. The clinical outcomes stroke, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, peripheral arterial disease, dementia and death will be adjudicated by an independent outcome committee in each country.

Study logistics

The overall study logistics are shown in figure 2. In this trial, each participant will make three visits to the study centre. After the prescreening by telephone, the first (screening) visit will take place. Informed consent will be signed by every participant. Eligibility criteria will be checked by recording blood pressure, weight, height, hip and waist circumference, cognition (Mini-Mental State Examination32) and medical history. Blood pressure will be measured twice with an Omron M6 Comfort (HEM-7321-E) device in resting sitting position. After this visit the participants are requested to fill in seven online self-assessment questionnaires at home: Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors physical activity questionnaire,33 a nutrition questionnaire (adapted from ePredice34), 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),35 Late Life Function and Disability Instrument (only disability part),36 EuroQol EQ5D-3L,37 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (only anxiety part)38 and the Partners in Health scale39 (participant rated self-management measure). Validated versions of these questionnaires in the local languages (Finnish, French, Dutch) will be used, whenever available. If not, the validated English version of the questionnaire was translated according to the proper translation guideline40 into the three languages.

Figure 2.

Study logistics.

Before the baseline visit, a fasting blood sample will be drawn for determining blood glucose, glycated haemoglobin, cholesterol spectrum, C-reactive protein and DNA storage. DNA will be stored locally, but is considered as one biobank. During the second (baseline) visit, which will take place ∼2 weeks after the screening visit, all outcome assessment instruments will be applied. Physical functioning will be assessed using the short physical performance battery.41 Medication use and results of blood tests will be recorded. Cognitive function in different domains will be tested using the Stroop test,42 auditory verbal learning test43 44 and semantic verbal fluency test (animal naming). For the intervention group this visit will be concluded with a motivational interview by the coach and an explanation of the platform to facilitate its use.

At 12 months, the participants are requested to fill in all seven online self-assessment questionnaires again and will receive a telephone evaluation call. Participants from both groups will be called and medication lists will be checked. The participants from the intervention group will have an additional interview with a strong focus on their motivation with their own coach.

At the end of study visit at 18 months all parameters assessed during screening and baseline visits and the online questionnaires are recorded again by an independent assessor, blinded to treatment allocation.

The electronic case report forms are built into the platform and only available for the assessors and researchers. All data will be coded, to assure confidentially. Data will be managed in one central server for all three countries.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants are randomised during the baseline visit in a 1:1 ratio using central randomisation according to a computer-generated randomisation sequence. We decided not to stratify for any characteristic, since the magnitude of the sample size, even within one country, renders any imbalance between the groups extremely unlikely.45 46 In case of spouse/partner participation, partners will be allocated to the same treatment arm to prevent contamination. It is explained to participants that they are randomised to one of two internet-platforms to improve lifestyle, without further details.

The coaches who support the participants in the intervention group are not blinded. Outcome assessment at the end of study at month 18 will be carried out by an independent assessor blinded to treatment allocation.

Safety

The intervention is considered low-risk, since no drugs are prescribed and only lifestyle advice and support is provided. Serious adverse events (AE) resulting from the intervention are not expected. No data safety and monitoring board is installed. AEs are however monitored using a 3-monthly questionnaire to be filled in online by the participant in both treatment arms. If the participant is not able to fill in the questionnaire due to a medical condition, the informant will be contacted to fill in the questionnaire. This questionnaire is automatically generated and concerns new cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, angina pectoris, peripheral arterial disease, diabetes mellitus), GP visits and institutionalisation. A logistic algorithm was designed to optimise data collection on AEs and end point during the study (figure 3) and minimise missing data on outcomes.

Figure 3.

Periodic end point and adverse events check questionnaire during trial. AE, adverse event; AEQ, adverse event/end point questionnaire; C, coach or research assistant; CVD, cardiovascular disease; P, participant.

Statistical analyses

Sample size

We originally based our power calculation on proportions. With advancing insight we decided on a continuous primary outcome, resulting in a new sample size calculation, again taking into account the effect of participants randomised as couples. We base the new sample size calculation on the effect-sizes of the HATICE primary outcome as observed in the preDIVA and FINGER trials.14 27 In the PreDIVA study the mean difference in z-score of the HATICE primary outcome between baseline and two year follow-up is 0.070 (p=0.002; intervention group −0.194 and control group −0.124). In the FINGER study this mean difference is 0.041 (p=0.11; intervention group −0.128 and control group −0.087). To avoid the risk of being underpowered since the effect was non-significant in the FINGER study, we base our sample size calculation on an effect size of 0.06.

Based on the first 1000 recruitments, we estimate that 17.5% of the participants will be recruited as a couple. Couples can be considered the smallest possible clusters (n=2). Although intra-cluster correlation coefficients (ICC) in RCTs are typically below 0.05, the ICC for vascular and lifestyle-related risk factors within small clusters of relatives may be much higher, up to 0.25.47

With 80% power, a 0.05 two-sided significance level, accounting for an estimated 14% attrition based on previous experiences in our own multi-domain prevention study,14 an ICC of 0.2547 and an effect size of 0.06 the required sample size is estimated to be 2534 participants in total. To allow for unexpected factors we raise this to 2600.

Because the meaning of a difference in z-scores is difficult to interpret, we estimated the threshold for a clinically relevant difference in z-score by using the follow-up data in preDIVA for clinical outcomes. For this purpose we compared preDIVA participants who did develop CVD or dementia with those who didn't during an average follow-up of 6.7 years. In preDIVA the change in z-score after 2 years was −0.205 in participants who developed CVD or dementia and −0.146 in participants who did not develop CVD or dementia. We therefore assume that a difference of 0.059 on the composite primary outcome of HATICE can be considered as clinically relevant.

Data analysis

For the primary analyses we will use a univariate general linear model to assess the effect on the primary outcome. All analyses will be according to the intention-to-treat principle. No imputation of the primary outcome will be made for the primary analysis. If there are significant differences in baseline characteristics, these will be adjusted for in secondary analyses. We will evaluate country, centre and coach differences and if indicated, this will also be adjusted for in secondary analyses.

The effect on the individual variables of the composite outcome (ie, blood pressure, BMI, LDL) and on the 10-year cardiovascular disease risk calculated using the Framingham risk score will be analysed using general linear models. Since the Framingham risk score is heavily influenced by age, the calculation of the risk score after 18 months will be carried out using the baseline age, in order to prevent obscuration of a true treatment effect by increasing age. For clinical dichotomous secondary outcomes, including incident cardiovascular disease and mortality, standard Cox-proportional hazards models will be used.

Self-assessment scales, which are mostly ordinal, will be analysed as linear scales where possible. If a self-assessment instrument has a defined cut-off for the presence or absence of a condition, (eg, the GDS) χ2 statistics will be used.

The full statistical analysis plan will be produced prior to the data analysis.

Economic evaluation

The economic evaluation of this trial will be performed as a cost-effective analysis (CEA) with the costs per patient with a reduced risk of CVD and cognitive decline as outcome parameter. Additionally, a cost-utility analysis (CUA) will be performed with the costs per quality adjusted life year (QALY) as outcome parameter. A healthcare perspective will be taken with a comparative assessment of the most relevant medical costs. These include the costs of hospital visits, emergency room visits, visits to the GP or a physician and institutionalisation for the two study groups. We will take the additional costs associated with implementing this intervention into account. Owing to the inclusion criteria for age, the vast majority of participants will be retired and therefore costs of loss of productivity are not taken into account. Unit costing will be based on national guidelines for costing in healthcare research.

The EQ-5D-3L will be used to generate health status scoring profiles over time and this will be transposed into QALY's. Incremental cost-effectiveness analyses will be performed to estimate the extra costs per additional patient with a reduced risk of CVD and cognitive decline as well as the extra costs per QALY. Country-specific subgroup analyses will be performed to account for differences in healthcare delivery.

Depending on the outcomes of the CEA and CUA it will be assessed whether a modelling scenario of internet counselling with a lifetime horizon is opportune and if so, how it should be elaborated.

The opportunity arises if the intervention proves effective, the health states at the end of the 18 months of follow-up differ between the groups and such difference in health states is expected to have an impact on need for healthcare for the remainder of their lifetime. If so, the groups will continue to differ by their costs of healthcare and the costs per QALY may shift for the better. If the 18 months costs per QALY are already acceptable against existing standards of societal willingness to pay per QALY at the time of analysis and further improvement is expected, then no modelling scenario is needed to underpin reimbursement decisions. If the costs per QALY are unacceptable despite proven effectiveness, then modelling is needed to find out the impact of the lifetime perspective on the cost-effectiveness acceptability of the lifestyle internet platform. Modelling of costs and QALYs from a lifetime perspective combines study and literature data on costs and QALYs in different stages of cardiovascular disease and/or cognitive impairment on the one hand with literature data on risks (hazard rates) of disease progression. If modelling seems opportune, then the current study will include the design for a subsequent modelling study.

Discussion

In HATICE, we will study the effect of an internet intervention to improve lifestyle-related risk factors for CVD, with the aim to improve the whole cardiovascular risk profile and preventing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, including cognitive decline. The wide and still growing access and use of the internet offers an excellent possibility to deliver an eHealth intervention in a scalable and cost-effective way. By focusing on the perspective of older people during the development phase, we have built an intuitive, easy to use platform, allowing for widespread use among older adults with only limited computer skills. The pilot of this study showed that the platform was easy to use and appreciated by the participants.

Improvement in physical activity can already be reached by regular walking, exercise groups and brief exercise advice by mail in a cost-effective way.50 A Cochrane meta-analysis showed that interactive computer-based interventions are effective for weight loss and weight maintenance.51 Also, support and self-management in changing lifestyle leads to improved health outcomes,47 52 and a stronger long-term effect.53 Using an innovative interactive approach based on the stimulation of self-management with coach support in HATICE can potentially lead to scalable and cost-effective methods to contribute to healthy ageing and the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline.

The choice of primary outcome was carefully made. A clinically relevant outcome parameter, such as incident cardiovascular disease or dementia, would have required a longer follow-up or a significantly larger sample size, both not deemed feasible. As such HATICE can be considered a large proof-of principle trial.

HATICE is a pragmatic trial, targeting a mixed population and delivering primary and secondary prevention. This precludes the use of one of the established cardiovascular risk scores (eg, Framingham,54 SCORE,55 which are validated for either primary or secondary prevention) as a primary outcome. Despite its limitations, a combined z-score of measurable risk factors is in our opinion the best reflection of an effect on the cardiovascular risk profile in a heterogeneous population with different risk factors present at baseline.

The different source populations will result in differences in characteristics of participants from the three countries. This resulting heterogeneity increases external validity of the results to a wider population and will allow for secondary analyses on the effect of the intervention in different populations.

The effects of the intervention can be quite different in each of the participating countries, since the implementation of cardiovascular risk management in these three countries is organised differently. The extensive experience of the research team in the different participating countries with large randomised prevention trials (FINGER,14 MAPT28 and PreDIVA27) in older populations facilitates the execution of this large RCT.

Although many older people use the internet nowadays, those who feel confident enough to participate in an eHealth trial might be higher educated. This will influence the generalisability and will have to be taken into account when interpreting the results particularly when assessing effect on cognition.

In our primary outcome we have included BMI. Although this may not be the best anthropometric parameter to reflect the risk of cardiovascular disease associated with obesity, it is the least subject to bias during assessment (as opposed to waist circumference or waist-hip ratio).

In spite of the blinded outcome assessment at the final follow-up visit, a certain degree of unblinding due to participant's expression of experiences with the platform might occur.

The pragmatic design of the intervention, independent of existing healthcare structures, will facilitate easy and wide implementation throughout Europe, if proven effective. The tailor-made character of the intervention specifically suited to the needs of older individuals fits with the current development towards a more personalised approach in medicine.

Ethical approval and dissemination

Results from this study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal electronically and in print.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the whole HATICE consortium for their contribution to this study. The authors thank the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) for the funding of the trial. The authors thank Pim Happel and Matthijs van Dorp for their substantial contribution in building the platform.

Footnotes

Collaborators: On behalf of the HATICE consortium.

Contributors: ER and SJ were responsible for the drafting of the manuscript. ER, MK, SA, HS, CB, WAvG, EPMvC and BvG were responsible for the study conception. All authors were responsible for the study design and provided professional or statistical support. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The HATICE trial is funded by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number 305374.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Medical Ethics Committee (MEC) of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Comité de Protection des Personnes (CPP) Sud Ouest et Outre Mer in France and the Northern Savo Hospital District Research Ethics Committee in Finland.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nichols M, Townsend N, Luengo-Fernandez R et al. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2012. Brussels: European Heart Network, 2012.

- 2.Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends London: Alzheimer's Disease International (ADI), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B, eds. Global Atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Policies, strategies and interventions. World Health Organisation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42:2672–713. 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:CD004816 10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turnbull F, Neal B, Ninomiya T et al. Effects of different regimens to lower blood pressure on major cardiovascular events in older and younger adults: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2008;336:1121–3. 10.1136/bmj.39548.738368.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mons U, Muezzinler A, Gellert C et al. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular events and mortality among older adults: meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies of the CHANCES consortium. BMJ 2015;350:h1551 10.1136/bmj.h1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 1981;282:1847–51. 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moran AE, Odden MC, Thanataveerat A et al. Cost-effectiveness of hypertension therapy according to 2014 guidelines. N Engl J Med 2015;372:447–55. 10.1056/NEJMsa1406751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE et al. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer's disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:788–94. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferson AL, Hohman TJ, Liu D et al. Adverse vascular risk is related to cognitive decline in older adults. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;44:1361–73. 10.3233/JAD-141812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strandberg TE, Pitkala KH, Berglind S et al. Multifactorial intervention to prevent recurrent cardiovascular events in patients 75 years or older: the Drugs and Evidence-Based Medicine in the Elderly (DEBATE) study: a randomized, controlled trial. Am Heart J 2006;152:585–92. 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uthman OA, Hartley L, Rees K et al. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;8:CD011163 10.1002/14651858.CD011163.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:2255–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Association of Echocardiography, European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012): the Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;19(4):585–667. 10.1177/2047487312450228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang KC, Soljak M, Lee JT et al. Coverage of a national cardiovascular risk assessment and management programme (NHS Health Check): Retrospective database study. Prev Med 2015;78:1–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G et al. EUROASPIRE III. Management of cardiovascular risk factors in asymptomatic high-risk patients in general practice: cross-sectional survey in 12 European countries. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:530–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann DM. Resistant disease or resistant patient: problems with adherence to cardiovascular medications in the elderly. Geriatrics 2009;64:10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McManus RJ, Mant J, Bray EP et al. Telemonitoring and self-management in the control of hypertension (TASMINH2): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:163–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60964-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H et al. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA 2002;288:2469–75. 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2006;295:180–9. 10.1001/jama.295.2.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementia. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:487–99. 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70141-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richard E, Andrieu S, Solomon A et al. Methodological challenges in designing dementia prevention trials — the European Dementia Prevention Initiative (EDPI). J Neurol Sci 2012;322:64–70. 10.1016/j.jns.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seybert H. Internet use in households and by individuals in 2012—Eurostat 2012. http://www.websm.org/uploadi/editor/1367569624Internet_use_in_households_and_by_individual_2012_Eurostat.PDF (accessed 1 Jun 2016).

- 25.Griffiths F, Lindenmeyer A, Powell J et al. Why are health care interventions delivered over the internet? A systematic review of the published literature . J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e10 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith DH, Neutel JM, Lacourciere Y et al. Prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded-endpoint (PROBE) designed trials yield the same results as double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with respect to ABPM measurements. J Hypertens 2003;21:1291–8. 10.1097/00004872-200307000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richard E, Van den Heuvel E, Moll van Charante EP et al. Prevention of dementia by intensive vascular care (PreDIVA): a cluster-randomized trial in progress. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:198–204. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819783a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillette-Guyonnet S, Andrieu S, Dantoine T et al. Commentary on “A roadmap for the prevention of dementia II. Leon Thal Symposium 2008.” The Multidomain Alzheimer Preventive Trial (MAPT): a new approach to the prevention of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2009;5:114–21. 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kivipelto M, Solomon A, Ahtiluoto S et al. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER): study design and progress. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:657–65. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doran GT. There's a S. M. A. R. T. way to write management goals and objectives . Management Review 1981;70:35–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Laatikainen T et al. Risk score for the prediction of dementia risk in 20 years among middle aged people: a longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:735–41. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70537-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC et al. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33:1126–41. 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tuomilehto J, Gabriel R. ePREDICE Early Prevention of Diabetes Complications in Europe 2011. http://www.epredice.eu.

- 35.Almeida OP, Almeida SA. Short versions of the geriatric depression scale: a study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jette AM, Haley SM, Coster WJ et al. Late life function and disability instrument: I. Development and evaluation of the disability component . J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M209–16. 10.1093/gerona/57.4.M209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16(3):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petkov J, Harvey P, Battersby M. The internal consistency and construct validity of the partners in health scale: validation of a patient rated chronic condition self-management measure. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1079–85. 10.1007/s11136-010-9661-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005;8:94–104. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994;49:M85–94. 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stroop J. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 1935;18:643–62. 10.1037/h0054651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rey A. L'examen clinique en psychologie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt M. Rey auditory verbal learning test: a handbook. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lachin JM. Properties of simple randomization in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1988;9:312–26. 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90046-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet 2002;359:515–19. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07683-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green BB, Cook AJ, Ralston JD et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, Web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:2857–67. 10.1001/jama.299.24.2857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2006;24:215–33. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000199800.72563.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lapointe J, Abdous B, Camden S et al. Influence of the family cluster effect on psychosocial variables in families undergoing BRCA1/2 genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Psychooncology 2012;21:515–23. 10.1002/pon.1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garrett S, Elley CR, Rose SB et al. Are physical activity interventions in primary care and the community cost-effective? A systematic review of the evidence. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e125–33. 10.3399/bjgp11X561249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wieland LS, Falzon L, Sciamanna CN et al. Interactive computer-based interventions for weight loss or weight maintenance in overweight or obese people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:Cd007675 10.1002/14651858.CD007675.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beishuizen CRL, Stephan BCM, van Gool WA et al. Web-based interventions targeting cardiovascular risk factors in people from middle age onwards: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e55 10.2196/jmir.5218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gagliardi AR, Faulkner G, Ciliska D et al. Factors contributing to the effectiveness of physical activity counselling in primary care: a realist systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:412–19. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:743–53. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conroy RM, Pyörälä K, Fitzgerald AP et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J 2003;24:987–1003. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00114-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]