Abstract

Objective To determine whether the treatment effect of apixaban versus warfarin differs with increasing numbers of concomitant drugs used by patients with atrial fibrillation.

Design Post hoc analysis performed in 2015 of results from ARISTOTLE (apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation)—a multicentre, double blind, double dummy trial that started in 2006 and ended in 2011.

Participants 18 201 ARISTOTLE trial participants.

Interventions In the ARISTOTLE trial, patients were randomised to either 5 mg apixaban twice daily (n=9120) or warfarin (target international normalised ratio range 2.0-3.0; n=9081). In the post hoc analysis, patients were divided into groups according to the number of concomitant drug treatments used at baseline (0-5, 6-8, ≥9 drugs) with a median follow-up of 1.8 years.

Main outcome measures Clinical outcomes and treatment effects of apixaban versus warfarin (adjusted for age, sex, and country).

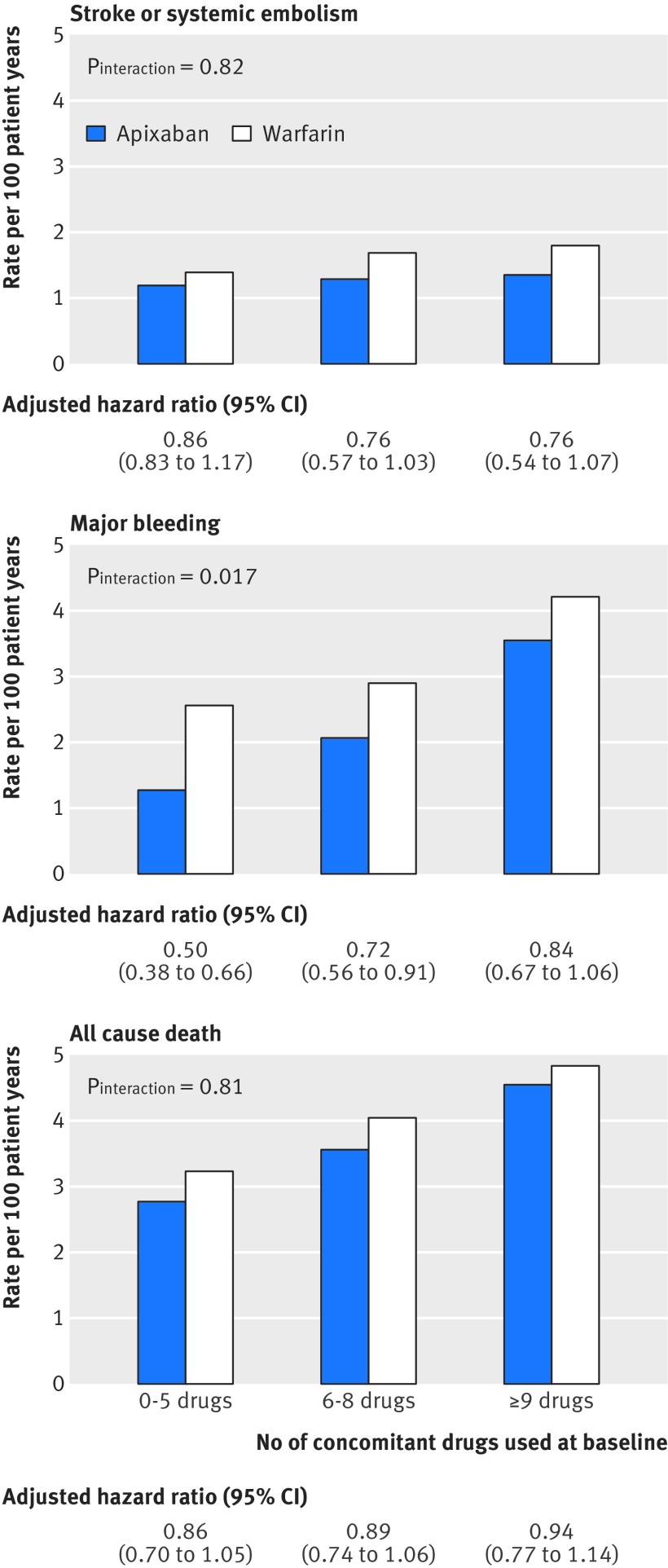

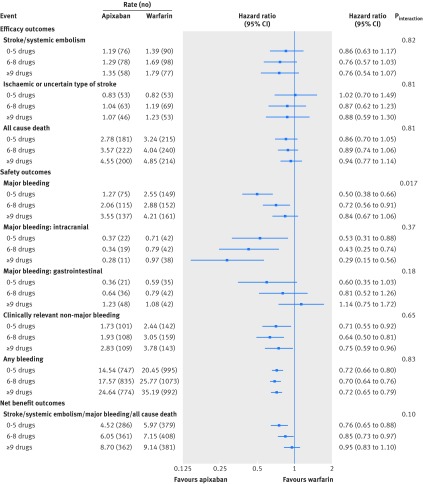

Results Each patient used a median of six drugs (interquartile range 5-9); polypharmacy (≥5 drugs) was seen in 13 932 (76.5%) patients. Greater numbers of concomitant drugs were used in older patients, women, and patients in the United States. The number of comorbidities increased across groups of increasing numbers of drugs (0-5, 6-8, ≥9 drugs), as did the proportions of patients treated with drugs that interact with warfarin or apixaban. Mortality also rose significantly with the number of drug treatments (P<0.001), as did rates of stroke or systemic embolism (1.29, 1.48, and 1.57 per 100 patient years, for 0-5, 6-8, and ≥9 drugs, respectively) and major bleeding (1.91, 2.46, and 3.88 per 100 patient years, respectively). Relative risk reductions in stroke or systemic embolism for apixaban versus warfarin were consistent, regardless of the number of concomitant drugs (Pinteraction=0.82). A smaller reduction in major bleeding was seen with apixaban versus warfarin with increasing numbers of concomitant drugs (Pinteraction=0.017). Patients with interacting (potentiating) drugs for warfarin or apixaban had similar outcomes and consistent treatment effects of apixaban versus warfarin.

Conclusions In the ARISTOTLE trial, three quarters of patients had polypharmacy; this subgroup had an increased comorbidity, more interacting drugs, increased mortality, and higher rates of thromboembolic and bleeding complications. In terms of a potential differential response to anticoagulation therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and polypharmacy, apixaban was more effective than warfarin, and is at least just as safe.

Trial registration ARISTOTLE trial, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00412984.

Introduction

In an era of increasing life expectancy, and with a growing population of survivors with various comorbidities, clinical decision making with regard to antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation has become an even greater clinical challenge.1 Despite the well appreciated risk of stroke, oral anticoagulation is often not prescribed in older people, and undertreatment has been associated with adverse outcomes.2 3 However, physicians increasingly acknowledge that treatment decisions should probably be based on biological age rather than chronological age.4

In various populations, polypharmacy has been associated with multiple comorbidities and frailty.5 6 7 8 9 10 Moreover, the risk of drug-drug interactions increases with the number of concomitant drug treatments. In addition, polypharmacy has been related to a higher risk of death and bleeding complications, also in patients with atrial fibrillation.6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 In this context, patients with polypharmacy could have a differential response to anticoagulation therapy.

With the introduction of apixaban, a safer alternative to warfarin has become available that has also proven to be of value in patients considered unsuitable for warfarin treatment.18 19 In a previous report, we demonstrated that the benefits of apixaban versus warfarin were irrespective of age (<65 years v 65-74 years v ≥75 years).20 However, among the elderly population, there are patients with hardly any comorbidity, whereas there are also younger patients with clinically significant comorbidity. On average, patients with atrial fibrillation use about four to six different drug treatments.10 11 21 Given that polypharmacy is generally defined as the use of five or more concomitant drug treatments, and thus represents an everyday issue, additional information on the effect of oral anticoagulation drugs in this subset of patients is of clinical importance.22 Especially in the case of apixaban, information on the effect of potentiating drugs is limited, and is of interest in patients treated with many concomitant drugs.

In this context, we performed a post hoc analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial (apixaban for reduction of stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation) to assess the association between the number of drugs used and the extent of comorbidity and adverse outcome.19 In addition, we looked at the relative treatment effect of apixaban versus warfarin in relation to the number of concomitant drug treatments.

Methods

Patients

The study design and main outcomes of the ARISTOTLE trial have been reported previously.19 23 In brief, ARISTOTLE was a multicentre, double blind, double dummy trial comparing apixaban with warfarin performed in 2006-11. Patients with documented atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter were eligible for inclusion if one or more of the following risk factors for thromboembolism were present: symptomatic heart failure within three months before inclusion or left ventricular function 40% or less; hypertension requiring pharmacological treatment; age 75 years or older; diabetes mellitus; and prior stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or systemic embolus.

Exclusion criteria included clinically significant mitral stenosis, conditions other than atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation, required aspirin treatment in a dose more than 165 mg/day or used in combination with a thienopyridine, recent ischaemic stroke, atrial fibrillation due to reversible causes, an increased bleeding risk considered to be a contraindication for oral anticoagulation, and severe renal insufficiency (that is, serum creatinine >221.0 μmol/L or calculated creatinine clearance <0.42 mL/s).

Patients were randomised to either 5 mg apixaban twice daily (n=9120) or a dose adjusted regimen of warfarin (n=9081). The target range for the international normalised ratio was 2.0 to 3.0, using a blinded encrypted point of care device. If two or more of the following criteria were present at baseline, patients received an apixaban dose of 2.5 mg twice daily or matching placebo: age 80 years or older, body weight up to 60 kg, serum creatinine 132.6 μmol/L or more. The study was approved by appropriate ethical committees at all sites and all patients provided written informed consent.

Concomitant drug treatments and comorbidity

To investigate the association between the number of concomitant drugs and the extent of comorbidity, we assessed the number of drugs used for each patient. The study drug (apixaban or warfarin) and the matching placebo were counted as one drug. All treatments were categorised by drug class, according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.24 Polypharmacy was defined as the use of five or more concomitant drugs.22

The use of drugs known to interact with apixaban or warfarin was assessed for each patient. For apixaban, we studied drugs known to inhibit both the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 enzyme as well as the P-glycoprotein as depicted by the US Food and Drug Administration.25 For warfarin, we studied the use of drugs known to inhibit or potentiate its anticoagulant effect with a high probability according to the American College of Chest Physicians guideline.26

All analyses performed were based on the baseline medication burden. Only for the anticoagulant we studied premature permanent discontinuation of the study drug; for patients assigned to warfarin, we calculated the time in therapeutic range according to the Rosendaal method.27

Per protocol—the use of any concomitant drugs during the trial—was left to the discretion of the treating physician. The following concomitant drugs were prohibited in combination with the study drug: potent inhibitors of CYP3A4 (eg, azole antifungals, macrolide antibiotics, protease inhibitors, and nefazadone), aspirin taken as a daily dose of more than 165 mg, other anticoagulant agents (eg, unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, direct thrombin inhibitors, pentasaccharides), and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. If these agents were used during trial participation, the study drug was to be (temporarily) interrupted and restarted as soon as the prohibited drug was discontinued. During the trial, it was also advised to cautiously use aspirin in combination with a thienopyridine, chronic daily use of a non-steroid anti-inflammatory agent, and cytotoxic or myelosuppressive therapy.

Clinical outcomes

We assessed outcomes in relation to the number of concomitant drug treatments used at the time of randomisation, during a median follow-up of 1.8 years (interquartile range 1.3-2.3 years). The primary efficacy outcome was stroke (that is, abrupt onset of focal neurological symptoms lasting at least 24 h) or a systemic embolism (that is, symptoms suggestive of an acute loss of blood flow to a non-cerebral artery, supported by evidence of embolism from surgical specimens, autopsy, angiography, or other objective testing). Key secondary efficacy outcomes included assessment of the type of stroke (ischaemic, haemorrhagic, or unspecified) and all cause death.

The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding according to the criteria set by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, which includes any clinically overt bleeding event accompanied by one or more of the following: haemoglobin drop of 20 g/L or more over a 24 h period, transfusion of two or more units of packed red blood cells, bleeding at a critical site (that is, intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, intra-articular, pericardial, intramuscular with compartment syndrome, or retroperitoneal), or fatal bleeding.28 Moreover, clinically relevant non-major bleeding events were monitored, and were defined as all clinically overt bleeding not meeting the criteria of major bleeding but leading to hospital admission, physician guided medical or surgical treatment, or a change in antithrombotic therapy. We defined the combined endpoint of net benefit as the combination of death, stroke, systemic embolism, and major bleeding.

Statistical analysis

This post hoc analysis of ARISTOTLE was performed in 2015. Based on the tertiles of the distribution of the number of concomitant drugs used at baseline (that is, 0-5, 6-8, and ≥9 drugs), patients were classified in groups. Comorbidities, organised by organ system, were summarised for the three groups, as well as other baseline characteristics. A similar approach was followed for the different drug classes. Data were depicted as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. We used one way analysis of variance and χ2 tests to compare groups. Efficacy, safety, and net benefit endpoints were compared among the three groups using rates per 100 patient years of follow-up and adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Adjusted hazard ratios were derived using Cox regression models adjusting for sex and age and country of randomisation. In these models, age was considered non-linear and included as a restricted cubic spline. We assessed the randomised treatment effect within each group (0-5, 6-8, ≥9 drugs) using a Cox regression model to estimate hazard ratios for apixaban versus warfarin along with 95% confidence intervals. The homogeneity of the randomised treatment effect across groups was tested by adding interaction terms to the Cox regression model.

The proportional hazard assumption was evaluated using scaled Schoenfeld residuals and no clinically relevant departure from the assumption was observed. All the analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in designing the study, in assessing the burden of the intervention on patients, or in explicitly setting outcome measures; however, outcomes were chosen to reflect daily practice described in earlier studies.29 Final study results of the ARISTOTLE trial were disseminated to study participants through their treating physicians.

Results

Baseline characteristics and comorbidity

Table 1 depicts baseline characteristics of the study population, categorised by groups of the number of drug treatments. The randomised treatment was well balanced across groups, and no relevant differences between apixaban and warfarin was observed for any of the drug categories across the population (supplementary table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of ARISTOTLE trial participants, by number of concomitant drugs used

| Characteristic | No of drugs | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-5 (n=6943) | 6-8 (n=6502) | ≥9 (n=4756) | ||

| Age (years, mean (SD)) | 68 (10) | 69 (10) | 71 (9) | <0.001 |

| Male | 4687 (67.5) | 4107 (63.2) | 2991 (62.9) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg, mean (SD)) | 81 (19) | 84 (21) | 89 (23) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (mean (SD)) | 28.2 (5.4) | 29.5 (6.0) | 30.7 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Previous use of vitamin K antagonists >30 days | 3555 (51.2) | 3656 (56.2) | 3190 (67.1) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL, mean (SD)) | 1.02 (0.24) | 1.06 (0.28) | 1.12 (0.32) | <0.001 |

| Region of enrolment | ||||

| North America | 736 (10.6) | 1353 (20.8) | 2385 (50.1) | <0.001 |

| Latin America | 1809 (26.1) | 1306 (20.1) | 353 (7.4) | |

| Europe | 3128 (45.1) | 2811 (43.2) | 1404 (29.5) | |

| Asia | 1270 (18.3) | 1032 (15.9) | 614 (12.9) | |

| HAS-BLED score (mean (SD)) | 1.45 (0.96) | 1.77 (1.02) | 2.25 (1.05) | <0.001 |

| CHADS2 score (mean (SD)) | 1.87 (1.02) | 2.15 (1.08) | 2.44 (1.17) | <0.001 |

| CHADS2 score | ||||

| ≤1 | 3093 (44.5) | 2057 (31.6) | 1033 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 2309 (33.3) | 2400 (36.9) | 1807 (38.0) | |

| ≥3 | 1541 (22.2) | 2045 (31.5) | 1916 (40.3) | |

| Randomised group | ||||

| Apixaban | 3424 (49.3) | 3320 (51.1) | 2376 (50.0) | 0.13 |

| Warfarin | 3519 (50.7) | 3182 (48.9) | 2380 (50.0) | |

| Low dose apixaban/placebo received (2.5 mg twice daily) | 253 (3.6) | 288 (4.4) | 290 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1795 (25.9) | 2184 (33.6) | 2063 (43.4) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 564 (8.1) | 985 (15.2) | 1036 (21.8) | <0.001 |

| History of percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting | 369 (5.3) | 815 (12.5) | 1292 (27.2) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure within 3 months | 1931 (27.8) | 2194 (33.7) | 1416 (29.8) | <0.001 |

| At least moderate valvular heart disease | 926 (13.4) | 1192 (18.3) | 1116 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| Syncope in past 5 years | 258 (3.7) | 279 (4.3) | 322 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension with pharmacological treatment | 5844 (84.2) | 5762 (88.6) | 4310 (90.6) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 193 (2.8) | 290 (4.5) | 401 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Aortic aneurysm | 46 (0.7) | 84 (1.3) | 139 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Neurological/cerebrovascular comorbidities | ||||

| Carotid stenosis | 54 (0.8) | 93 (1.4) | 190 (4.0) | <0.001 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 302 (4.4) | 315 (4.8) | 337 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 808 (11.6) | 750 (11.5) | 569 (12.0) | 0.77 |

| Dementia | 22 (0.4) | 29 (0.5) | 45 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Epilepsy | 22 (0.4) | 49 (0.8) | 41 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 435 (6.3) | 626 (9.7) | 889 (18.7) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 157 (2.3) | 250 (3.9) | 462 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Sleep Apnoea | 145 (2.1) | 262 (4.0) | 606 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal comorbidities | ||||

| Dyspepsia | 374 (5.4) | 445 (6.9) | 556 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 315 (4.5) | 527 (8.1) | 1074 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 383 (5.5) | 417 (6.4) | 406 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal surgery | 509 (7.3) | 606 (9.3) | 575 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 190 (2.7) | 193 (3.0) | 121 (2.5) | 0.39 |

| Endocrine comorbidities | ||||

| Hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism | 429 (6.2) | 733 (11.3) | 878 (18.5) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 806 (11.6) | 1603 (24.7) | 2138 (45.0) | <0.001 |

| End organ damage due to diabetes mellitus | 75 (1.1) | 219 (3.4) | 459 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal comorbidities | ||||

| Falls within 1 year | 140 (2.3) | 215 (3.6) | 398 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Previous non-traumatic fracture | 299 (4.3) | 339 (5.2) | 436 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 151 (2.2) | 298 (4.6) | 521 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Renal comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 434 (6.3) | 520 (8.0) | 553 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| Creatine clearance <50 mL/min | 927 (13.4) | 1112 (17.2) | 970 (20.5) | <0.001 |

| Haematological comorbidities | ||||

| History of Anemia | 210 (3.0) | 359 (5.5) | 676 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelet at baseline <150×109/L) | 510 (7.6) | 467 (7.4) | 332 (7.2) | 0.77 |

| Bleeding history | 779 (11.2) | 1029 (15.8) | 1232 (25.9) | <0.001 |

| No of organ systems affected (median (IQR)) | 2, 1-3 | 2, 2-3 | 3, 2-4 | <0.001 |

Data are no (%) of patients unless stated otherwise. Subcategorisation of all baseline characteristics per treatment allocation is presented in web table 1. CHADS2=congestive heart failure, hypertension, age (≥75 years), diabetes mellitus, and previous stroke/transient ischaemic attack/systemic embolism (doubled risk weight); HAS-BLED=uncontrolled hypertension, abnormal renal and liver function, prior stroke, bleeding history (or predisposition), labile international normalised ratio, age>65 years, drugs predisposing to bleed, and alcohol use disorders; IQR=interquartile range; SD=standard deviation.

Patients using more drug treatments were older, more often female, and less often warfarin naive at study entry (table 1). The CHADS2 and HAS-BLED scores increased with the increasing number of concomitant drug treatments. With the increasing number of drugs, the associated comorbidity increased significantly (table 1).

Concomitant drugs—classification according to organ or system

The median number of drug treatments used was six (interquartile range 5-9) and polypharmacy was present in 13 932 (76.5%) patients (supplementary fig 1). Among the 18 201 ARISTOTLE participants, we saw marked regional differences in the number of drugs used: 53% (2385/4474) of patients enrolled in North America used nine or more drugs (United States 1980/3417 (58%); Canada 405/1057 (38%)), compared with 10-21% for the other regions (table 1). Although there were more patients with comorbidity in four or more organ systems in the USA than in non-US countries (1389 (43.3%) v 2602 (20.5%)), we observed a greater number of drugs used in the USA regardless of the number of comorbidities.

Across groups of increasing number of drugs, the median number of represented drug classes increased from two (interquartile range two to three) to five (four to five), for patients using up to five drugs and for those using nine or more drugs, respectively.

Table 2.

Distribution of drug classes used by ARISTOTLE trial participants, by number of concomitant drugs used

| Drug class | No of drugs | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-5 (n=6943) | 6-8 (n=6502) | ≥9 (n=4756) | ||

| Alimentary tract and metabolism | 962 (13.9) | 3045 (46.8) | 4094 (86.1) | <0.001 |

| Blood and blood forming organs (excluding apixaban/warfarin) | 2282 (32.9) | 4322 (66.5) | 4116 (86.5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular system | 6460 (93.0) | 6468 (99.5) | 4737 (99.6) | <0.001 |

| Dermatological drugs | 34 (0.5) | 96 (1.5) | 346 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Genitourinary system and sex hormones | 173 (2.5) | 510 (7.8) | 936 (19.7) | <0.001 |

| Systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulins | 181 (2.6) | 508 (7.8) | 852 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Anti-infective drugs for systemic use | 44 (0.6) | 161 (2.5) | 347 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 14 (0.2) | 60 (0.9) | 152 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 202 (2.9) | 688 (10.6) | 1350 (28.4) | <0.001 |

| Nervous system | 523 (7.5) | 1448 (22.3) | 2376 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| Antiparasitic products, insecticides, and repellents | 0 (0.0) | 13 (0.2) | 46 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory system | 164 (2.4) | 600 (9.2) | 1336 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| Sensory organs | 41 (0.6) | 115 (1.8) | 300 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Various | 126 (1.8) | 247 (3.8) | 630 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Interacting drugs | ||||

| ≥1 combined P-glycoprotein and weak-moderate-strong CYP3A4 inhibitor | 1128 (16.2) | 1431 (22.0) | 1301 (27.4) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 combined P-glycoprotein and weak-moderate-strong CYP3A4 inducer | 12 (0.2) | 34 (0.5) | 47 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 highly probable VKA inhibiting drug | 8 (0.1) | 19 (0.3) | 33 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 highly probable VKA potentiating drug | 973 (14.0) | 1406 (21.6) | 1387 (29.2) | <0.001 |

| Use of acetylsalicylic acid, NSAIDs, or prednisone | 956 (13.8) | 2064 (31.7) | 2362 (49.7) | <0.001 |

Data are no (%) of patients. CYP=cytochrome P450; VKA=vitamin K antagonist, NSAIDs=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Across the three study groups, there were no relevant differences between apixaban and warfarin regarding the proportion of patients in each of the defined drug classes. For each of the respective drug classes, the proportion of patients increased statistically significantly from the group using up to five concomitant drugs to the group using nine or more concomitant drugs. Across groups of increasing concomitant medication, the proportion of patients in the respective drug classes was higher in the USA than in non-US countries (supplementary table 2A and 2B). Despite this difference in prescription pattern, we saw a clear association between the number of concomitant drugs used at baseline and the number of comorbidities, both for the US and non-US populations.

Clinical outcomes according to the number of concomitant drugs

Efficacy outcomes

With regard to the primary efficacy endpoint (stroke and systemic embolism), patients using more concomitant drugs were at higher risk, with an increase in event rates from 1.29 per 100 patient years for patients using up to five drugs to 1.57 per 100 patient years for patients using nine or more drugs (P<0.001; table 3). For the secondary efficacy outcomes, there was also a significant association with the number of concomitant drugs. We saw a twofold increased risk for all cause death for patients using nine concomitant drugs or more compared with those using up to five concomitant drugs (P<0.001).

Table 3.

Efficacy and safety outcomes by number of concomitant drug treatments used by ARISTOTLE trial participants

| Event | 0-5 drugs | 6-8 drugs | ≥9 drugs | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate per 100 patient years (no of patients) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Rate per 100 patient years (no of patients) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Rate per 100 patient years (no of patients) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Efficacy outcomes | |||||||||

| Stroke/SE | 1.29 (166) | Reference | 1.48 (176) | 1.270 (1.022 to 1.577) | 1.57 (135) | 1.539 (1.190 to 1.991) | 0.004 | ||

| Ischaemic or uncertain type of stroke | 0.82 (106) | Reference | 1.11 (132) | 1.475 (1.136 to 1.915) | 1.15 (99) | 1.738 (1.275 to 2.369) | 0.001 | ||

| All cause death | 3.01 (396) | Reference | 3.80 (462) | 1.409 (1.229 to 1.616) | 4.70 (414) | 2.031 (1.735 to 2.377) | <0.001 | ||

| Safety outcomes | |||||||||

| Major bleeding | 1.91 (224) | Reference | 2.46 (267) | 1.243 (1.036 to 1.491) | 3.88 (298) | 1.721 (1.414 to 2.095) | <0.001 | ||

| Intracranial | 0.54 (64) | Reference | 0.55 (61) | 1.025 (0.722 to 1.456) | 0.62 (49) | 1.153 (0.795 to 1.673) | 0.73 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 0.47 (56) | Reference | 0.71 (78) | 1.498 (1.062 to 2.111) | 1.15 (90) | 2.429 (1.740 to 3.391) | <0.001 | ||

| Clinically relevant non-major bleeding | 2.09 (243) | Reference | 2.47 (267) | 1.183 (0.994 to 1.408) | 3.30 (252) | 1.574 (1.319 to 1.877) | <0.001 | ||

| Any bleeding | 17.41 (1742) | Reference | 21.40 (1908) | 1.167 (1.092 to 1.247) | 29.63 (1766) | 1.452 (1.348 to 1.565) | <0.001 | ||

| Net benefit outcomes | |||||||||

| Stroke/SE/major bleeding/all cause death | 5.24 (665) | Reference | 6.59 (769) | 1.320 (1.187 to 1.468) | 8.92 (743) | 1.838 (1.631 to 2.071) | <0.001 | ||

| Other outcomes | |||||||||

| Permanent study drug discontinuation | 14.32 (1699) | Reference | 14.99 (1655) | 1.053 (0.982 to 1.129) | 17.44 (1372) | 1.218 (1.123 to 1.322) | <0.001 | ||

| Time in therapeutic range <66%* | 53.2 (1823) | Reference | 50.2 (1564) | 0.887 (0.805 to 0.977) | 44.9 (1044) | 0.716 (0.644 to 0.795) | <0.001 | ||

Hazard ratios and P values adjusted by country (strata), sex, and age (spline). SE=systemic embolism.

*Values reported are percentage (number of patients) and unadjusted odd ratios for patients randomised to warfarin.

Safety outcomes

The risk of major bleeding for patients using six or more concomitant drugs was significantly higher than for those using up to five drugs (using 0-5 drugs as reference group; 6-8 drugs: adjusted hazard ratio 1.24 (95% confidence interval 1.04 to 1.49); ≥9 drugs: 1.72 (1.41 to 2.10); table 3). When subdividing major bleeding according to the location, we observed no significant difference across groups for intracranial bleeding (P=0.73), while the event rate for gastrointestinal bleeding significantly increased with a higher number of concomitant drugs.

Net benefit outcome

With regard to the combined endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, and all cause death, event rates increased across groups (5.24, 6.59, and 8.92 per 100 patient years for 0-5, 6-8, and ≥9 drugs, respectively, P<0.001; table 3). This increase was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.84 (95% confidence interval 1.63 to 2.07) for patients using at least nine concomitant drugs compared with those using up to five concomitant drugs (table 3).

Other outcomes

With the use of increasing numbers of concomitant drugs, the risk of permanent discontinuation of study drug rose significantly (discontinuation rates 14.3, 15.0, and 17.4 per 100 patient years at risk for 0-5, 6-8, and ≥9 drugs, respectively, P<0.001; table 3). Poor control of the international normalised ratio during follow-up (that is, time in therapeutic range <66%) was highest in the patients using up to five concomitant drugs and decreased across the groups (53.2%, 50.2%, and 44.9% for 0-5, 6-8, and ≥9 drugs, respectively, P<0.001; table 3).

Treatment effect

Figures 1 and 2 outline the treatment effect of apixaban versus warfarin for the different study outcomes, categorised by the number of concomitant drugs used at baseline.

Fig 1 Association between randomised treatment and main outcomes, by number of concomitant drugs used at baseline by ARISTOTLE trial participants

Fig 2 Treatment comparisons for efficacy, safety, and net benefit outcomes between apixaban and warfarin according to the number of concomitant drugs used by ARISTOTLE trial participants at baseline

For the primary efficacy outcome, risk reductions of apixaban versus warfarin were consistent, irrespective of the number of concomitant drugs used (Pinteraction=0.82), with lower event rates on apixaban for all groups. Also for the secondary efficacy outcomes, no significant interactions were observed.

With regard to major bleeding, relative risk reductions for apixaban versus warfarin fell with increasing number of concomitant drugs (Pinteraction=0.017), corresponding to absolute rate reductions per 100 patient years of 1.28, 0.82, and 0.66 for the three groups (0-5, 6-8, and ≥9 drugs, respectively). For intracranial bleeding, the absolute benefit on apixaban showed a numerical increase across the groups, by contrast with the numerical differences in major gastrointestinal bleeding observed between treatment groups. With regards to the combined outcome of stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, and all cause death, we observed no significant interaction between treatment groups (P=0.10). Rates of permanent study drug discontinuation were lower for apixaban in all groups (Pinteraction=0.36).

Interacting drugs

The proportion of patients using an interacting drug increased across the groups of concomitant drug treatments, both for CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein inhibitors as warfarin potentiating drugs. At least one combined inhibitor of both the CYP3A4 enzyme and P-glycoprotein was used by 20.9% (1903/9120) of patients treated with apixaban, and 21.1% (1913/9081) of patients treated with warfarin used vitamin K antagonist potentiating drugs. For the concomitant use of aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or prednisone, proportions were 13.8%, 31.7%, and 49.7% for the three groups (0-5, 6-8, and ≥9 drugs, respectively; P<0.001).

Rates of major bleeding did not significantly differ between patients with or without combined CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein inhibitors (2.59 v 2.61 per 100 patient years, respectively). Moreover, no significant interaction with the treatment allocation was observed (P=0.39; table 4). With regard to drugs known to potentiate warfarin, we also observed no difference in the event rate of major bleeding for users versus non-users (2.60 v 2.61 per 100 patient years).

Table 4.

Major bleeding rates with apixaban or warfarin according to use of interacting drugs by ARISTOTLE trial participants

| Interacting drugs | Use of potentiating drug (rate per 100 patient years (no of patients)) | No use of potentiating drug (rate per 100 patient years (no of patients)) | Pinteraction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apixaban | Warfarin | Apixaban | Warfarin | |||

| ≥ 1 combined P-glycoprotein and weak/moderate/strong CYP3A4 inhibitor | 2.27 (72) | 2.91 (93) | 2.10 (255) | 3.14 (369) | 0.39 | |

| ≥1 highly probable VKA potentiating drug | 2.03 (62) | 3.16 (96) | 2.16 (265) | 3.07 (366) | 0.64 | |

CYP=cytochrome P450; VKA=vitamin K antagonist.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial, we observed that polypharmacy was present in three quarters of patients and that the number of concomitant drug treatments is associated with increased comorbidity. Prescription patterns differed across regions, with about twice the number of concomitant drugs used in the USA versus non-US countries. Adverse clinical outcomes occurred more frequently in patients treated with a higher number of concomitant drugs. The benefits of apixaban in reducing stroke were preserved, regardless of the number of concomitant drugs taken. In terms of safety, although rates of major bleeding were consistently lower with apixaban than with warfarin, the magnitude of benefit with apixaban decreased with the increasing number of concomitant drug treatments.

Polypharmacy and adverse outcomes

Atrial fibrillation affects older patients, who have a varying extent of comorbidity and associated concomitant drug treatments.30 Previous studies have reported rates of polypharmacy in 40-64% of patients with atrial fibrillation, with varying prescription patterns and inclusion and exclusion criteria.9 10

Various reports have demonstrated, for different clinical conditions, that polypharmacy is associated with increased comorbidity.5 6 7 8 9 10 In addition, studies focusing on older populations have linked polypharmacy to adverse drug reactions, falls, disability, and frailty.6 7 8 In this context, patients with polypharmacy could constitute a population with a differential response to oral anticoagulation.

Although differences in prescription thresholds could affect the classification of patients in individual cases, several reports have repeatedly demonstrated on a group level that polypharmacy is associated with comorbidity and adverse outcome, also in populations with atrial fibrillation.6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Our findings of higher risks of bleeding, stroke, and all cause mortality with increasing numbers of drugs are in line with these previous observations.

Notably, this increased risk of adverse outcomes should be placed in the context of the association between the number of drug treatments and comorbidities present at baseline, indicating a more frail status of patients with polypharmacy. If we were to adjust for these baseline differences, it is likely that the risk of adverse outcomes related to the number of drugs would diminish. However, we did not study the association between polypharmacy and adverse outcomes independent of the baseline difference. On the contrary, we studied the number of concomitant drugs as a marker of comorbidity or frailty, and adverse outcome.

As such, we performed adjustments limited to age, sex, and country of randomisation. It was important to adjust for region, given the differences in prescription patterns between countries that are independent of differences in comorbidity. It is striking that the USA had more use of polypharmacy than non-US countries, which was not solely explained by comorbidity.

Polypharmacy and treatment effect

Considering that patients with polypharmacy have a higher risk of adverse outcomes and multiple coexisting impairments, it is of special interest to study whether the main trial results of the ARISTOTLE study are consistent among patients using many concomitant drug treatments. For the primary endpoint of stroke and systemic embolism, we saw an absolute risk reduction from 1.60% per year with warfarin to 1.27% per year with apixaban (21% relative risk reduction in the complete population, which was consistent irrespective of the number of concomitant drugs used).19

Overall, the use of apixaban was associated with an absolute risk reduction in major bleeding from 3.09% to 2.13% per year when compared with warfarin (relative risk reduction 31%).19 However, we observed a significant treatment interaction with relative risk reductions of apixaban varying from 50% (0-5 drugs) to 28% (6-8 drugs) and 16% (≥9 drugs), respectively. Importantly, the risk reduction of intracranial bleeding did not diminish with an increasing number of concomitant drugs. Therefore, the fact that the relative benefit of apixaban over warfarin appears to diminish across groups is due to other types of major bleeding. For example, with increasing numbers of drug treatments, the numerical difference in gastrointestinal bleeding events shifts from a benefit for apixaban (0-5 drugs) to no apparent difference (≥9 drugs) between both oral anticoagulants.

The ROCKET AF trial, with overall similar rates of major bleeding for rivaroxaban and warfarin, also showed a treatment interaction for major bleeding.10 The hazard ratio for major bleeding in patients using fewer concomitant drugs (0-4) was lower than that observed in the entire study population (adjusted hazard ratio 0.69 (95% confidence interval 0.51 to 0.94) v 1.04 (0.90 to 1.20)). For mortality, there was no difference in treatment effect of rivaroxaban in patients with polypharmacy. In the ARISTOTLE trial, apixaban reduced the risk of mortality from 3.94% to 3.52% per year when compared with warfarin in the main study—a relative risk reduction of 11% that was consistent regardless of the number of concomitant drug treatments.19

In the ARISTOTLE trial as well as in the ROCKET AF trial, patients with polypharmacy were older.10 Nonetheless, the relative reduction of both apixaban and rivaroxaban on major bleeding proved to be consistent across the different age groups in previously reported post hoc analyses.20 31 Importantly, this implies that our findings cannot be inferred to older patients in general. In fact, our findings are irrespective of age and sex, and refer to the group of patients, both younger and older, with multiple comorbidities and drug treatments.

Possible explanations for the attenuation of the observed safety benefit of apixaban with increasing concomitant drugs include effects of comorbidity and drug-drug interactions, or the play of chance. We demonstrated that various coexisting diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal disease, renal impairment) were more frequent with increasing numbers of concomitant drugs. Of interest, given the consistent risk reduction of apixaban for intracranial bleeding, the treatment interaction for major bleeding is related to other major bleeding. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding complications (eg, previous gastric ulcers; gastrointestinal surgery; dyspepsia; use of aspirin, prednisone, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) were more prevalent among patients with polypharmacy. Other non-gastrointestinal risk factors for bleeding were also more often common in patients using more concomitant drugs (eg, older age, renal impairment, anaemia, diabetes, and previous bleeding).32

Other aspects that could account for the reduced benefit of apixaban in patients using nine concomitant drugs or more are the higher rates of permanent study drug discontinuation and lower proportion of patients who were vitamin K antagonist naive (supplementary table 1).33 The lower rates of patients on study medication may have blunted the observed risk reduction of apixaban in this group. In addition, bleeding rates on warfarin are usually lower in patients with prior experience vitamin K antagonists. Finally, the better control of international normalised ratio in the patients with more than nine concomitant drug treatments may have diminished bleeding rates on warfarin.34 35

For drug-drug interactions, we specifically studied the effect of warfarin potentiating drugs and the combination of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein inhibitors, given the possibility of higher plasma concentrations of apixaban with these agents. However, we saw no evidence of differential treatment effect between apixaban and warfarin across groups of the number of concomitant drugs when accounting for warfarin or apixaban potentiating drugs.

The effects of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with polypharmacy have also been studied in a pooled analysis of data, in the setting of secondary prevention after a venous thromboembolism.15 For major bleeding, there was no treatment interaction when comparing the safety of dabigatran versus warfarin in patients using three or fewer concomitant drugs with those using more than three concomitant drugs. However, these patients were much younger and less fragile than patients with atrial fibrillation.

With regards to symptomatic venous thromboembolism, the issue of a potential different response to oral anticoagulation therapy in patients considered to be fragile has been studied in more detail.36 In this study, patients were considered to be fragile if they were over 75 years old, had a low body weight (<50 kg), or had impaired renal function (creatinine clearance <0.83 mL/s). Although this certainly identifies patients at risk, incorporation of multiple comorbidities would allow for a more refined identification of frail patients within these specific subgroups.37

In summary, polypharmacy could be a marker of multimorbidity and a predictor of adverse outcomes, and it might provide a first general impression of a patient’s frailty. Future research on a differential response with oral anticoagulation therapy in patients with multimorbidity should focus on incorporation of the key frailty criteria. For example, the Fried criteria can help to identify higher risk patients who are often under-represented in clinical trials.38 This group may deserve additional attention, as far as the generalisability of trial data is concerned, not only in the field of anticoagulation therapy but also for other treatments.39

Study limitations

This study had several limitations. Firstly, it was a post hoc analysis, although there was a prospective, detailed analysis plan. Secondly, the analyses were based on the drug burden at baseline, without information on drug changes, reason, or appropriateness of drug prescription. However, with polypharmacy that is often driven by chronic medical conditions, substantial reductions in the number of drugs are not likely. Thirdly, as the number of drugs might not only be driven by the extent of comorbidity, but also by prescription patterns, we acknowledge that this might have affected classification on an individual level. However, on a group level, the use of polypharmacy has repeatedly demonstrated to be a marker of the extent of comorbidity and associated with adverse outcome.

The cut-off value of five or more drugs is arbitrary, although it has been used in many previous reports. Given that three quarters of patients would qualify for polypharmacy according to this definition, our statistical approach was not arbitrary, but based on a common approach of dividing our data into groups to explore polypharmacy across categories that are sufficiently large to avoid the hazard of small subgroups. With regard to generalisability, our findings might not apply to an unselected population with atrial fibrillation, given the selection that occurs when enrolling patients in clinical trials.

Conclusions

In this population with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation therapy, polypharmacy (≥5 drugs) was observed in three quarters of patients. The extent of comorbidity increased with greater numbers of concomitant drugs, which was irrespective of regional prescription patterns. Mortality, stroke, and major bleeding were also more frequent with increasing numbers of drugs. As for a potential differential response to anticoagulation therapy in this context, we observed that apixaban was superior to warfarin in terms of efficacy, regardless of the number of drugs taken, whereas its magnitude of benefit on major bleeding decreased with higher numbers of concomitant drugs. Important differences in the comorbidity profile could account for this, and it did not appear that warfarin or apixaban potentiating drugs (CYP3A4, P-glycoprotein inhibitors) explained this observed treatment interaction. In summary, apixaban is more effective than and is at least as safe as warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation, regardless of polypharmacy.

What is already known on this topic

Polypharmacy is associated with increased comorbidity, frailty, and drug-drug interactions, and has repeatedly been shown to be a marker of adverse clinical outcome; therefore, patients with polypharmacy could have a differential response to anticoagulation therapy

For patients with atrial fibrillation, apixaban has been more effective and safer than warfarin, but whether this also holds true for patients using many concomitant drugs is unknown

What this study adds

For patients with atrial fibrillation, apixaban was more effective than warfarin regardless of the number of concomitant drugs used

Although major bleeding rates were consistently lower with apixaban than with warfarin, the magnitude of benefit with apixaban seemed to decrease with the increasing number of concomitant drug treatments

In this patient group, the specific use of warfarin or apixaban potentiating drugs did not seem to account for this differential response to anticoagulation therapy with regard to major bleeding

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix: Supplementary materials

Contributors: All the authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, and the acquisition and interpretation of data for the work. DMW and LT conducted the data analysis. JJF, MAB, and FWAV drafted the work and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved of the final version for submission. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors had full access to the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CBG is the study guarantor.

Funding: The ARISTOTLE study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. The sponsors did not have any role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in writing the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: JJF has received consulting fees/honorariums from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, and Daiichi Sankyo; MAB has received consulting fees/honorariums from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, and Daiichi Sankyo; DMW, LT, FL, and JBW have nothing to report; RDL reports consulting fees/honorariums from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Pfizer, and Portola, and research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and GlaxoSmithKline; DX reports research grants to his institution from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cadila Pharma, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis; SH reports consulting fees/honorariums from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer, and research grants from GlaxoSmithKline; LW reports consulting fees/honorariums from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer, and research grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck/Schering-Plough, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics; JHA reports consulting fees/honorariums from Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Portola, and Somahlution, and research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Regado Biosciences, Sanofi, Tenax Therapeutics, and Vivus Pharmaceuticals; CBG reports consulting fees/honorariums from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman LaRoche, Janssen, Medtronic, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda, and The Medicines Company, and research grants from Armetheon, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; FWAV reports consulting fees/honorariums from AstraZeneca, BMS/Pfizer, Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Boehringer-Ingelheim.

Ethical approval: The ARISTOTLE study was approved by the appropriate ethics committees at all sites; all patients provided written informed consent.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1. GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117-71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 pmid:25530442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieuwlaat R, Olsson SB, Lip GYH, et al. Euro Heart Survey Investigators Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment is associated with improved outcomes compared with undertreatment in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2007;153:1006-12. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.008 pmid:17540203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scowcroft AC, Lee S, Mant J. Thromboprophylaxis of elderly patients with AF in the UK: an analysis using the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) 2000-2009. Heart 2013;99:127-32. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302843 pmid:23086966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S, Bajorek B. Pharmacotherapy in the ageing patient: the impact of age per se (a review). Ageing Res Rev 2015;24:99-110. 10.1016/j.arr.2015.07.006 pmid:26226330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Korhonen MJ, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Patterns of drug use and factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in elderly persons: results of the Kuopio 75+ study: a cross-sectional analysis. Drugs Aging 2009;26:493-503. 10.2165/00002512-200926060-00006 pmid:19591524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:989-95. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018 pmid:22742913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herr M, Robine JM, Pinot J, Arvieu JJ, Ankri J. Polypharmacy and frailty: prevalence, relationship, and impact on mortality in a French sample of 2350 old people. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:637-46. 10.1002/pds.3772 pmid:25858336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang R, Chen L, Fan L, et al. Incidence and effects of polypharmacy on clinical outcomes among patients aged 80+: a five-year follow-up study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142123 10.1371/journal.pone.0142123 pmid:26554710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Proietti M, Raparelli V, Olshansky B, Lip GYH. Polypharmacy and major adverse events in atrial fibrillation: observations from the AFFIRM trial. Clin Res Cardiol 2016;105:412-20. 10.1007/s00392-015-0936-y pmid:26525391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccini JP, Hellkamp AS, Washam JB, et al. Polypharmacy and the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban versus warfarin in the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2016;133:352-60. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018544 pmid:26673560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelhafiz AH, Wheeldon NM. Risk factors for bleeding during anticoagulation of atrial fibrillation in older and younger patients in clinical practice. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2008;6:1-11. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.03.005 pmid:18396243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagansky N, Knobler H, Rimon E, Ozer Z, Levy S. Safety of anticoagulation therapy in well-informed older patients. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:2044-50. 10.1001/archinte.164.18.2044 pmid:15477441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donzé J, Clair C, Hug B, et al. Risk of falls and major bleeds in patients on oral anticoagulation therapy. Am J Med 2012;125:773-8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.033 pmid:22840664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leiss W, Méan M, Limacher A, et al. Polypharmacy is associated with an increased risk of bleeding in elderly patients with venous thromboembolism. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:17-24. 10.1007/s11606-014-2993-8 pmid:25143224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldhaber SZ, Eriksson H, Kakkar A, et al. Influence of polypharmacy on the efficacy and safety of dabigatran versus warfarin for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism: a pooled analysis of RE-COVER and RE-COVER II. Circulation 2015;132:A12422. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Bleeding during antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:409-16. 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440040081009 pmid:8607726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wehinger C, Stöllberger C, Länger T, Schneider B, Finsterer J. Evaluation of risk factors for stroke/embolism and of complications due to anticoagulant therapy in atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2001;32:2246-52. 10.1161/hs1001.097090 pmid:11588308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, et al. AVERROES Steering Committee and Investigators. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:806-17. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007432 pmid:21309657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981-92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039 pmid:21870978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halvorsen S, Atar D, Yang H, et al. Efficacy and safety of apixaban compared with warfarin according to age for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: observations from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1864-72. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu046 pmid:24561548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nobili A, Marengoni A, Tettamanti M, et al. Association between clusters of diseases and polypharmacy in hospitalized elderly patients: results from the REPOSI study. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22:597-602. 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.08.029 pmid:22075287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:187-95. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02744.x pmid:16939529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes RD, Alexander JH, Al-Khatib SM, et al. ARISTOTLE Investigators. Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other ThromboemboLic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial: design and rationale. Am Heart J 2010;159:331-9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.035 pmid:20211292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (WHOCC). 2015. www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index.

- 25. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2014. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/DrugInteractionsLabeling/ucm093664.htm.

- 26.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. American College of Chest Physicians. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133(suppl):160S-98S. 10.1378/chest.08-0670 pmid:18574265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost 1993;69:236-9.pmid:8470047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulman S, Kearon C. Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 2005;3:692-4. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x pmid:15842354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, Pearce LA. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:492-501. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00003 pmid:10507957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lip GYH, Laroche C, Dan GA, et al. A prospective survey in European Society of Cardiology member countries of atrial fibrillation management: baseline results of EURObservational Research Programme Atrial Fibrillation (EORP-AF) Pilot General Registry. Europace 2014;16:308-19. 10.1093/europace/eut373 pmid:24351881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Wojdyla DM, et al. ROCKET AF Steering Committee and Investigators. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin among elderly patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the rivaroxaban once daily, oral, direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation (ROCKET AF). Circulation 2014;130:138-46. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005008 pmid:24895454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hylek EM, Held C, Alexander JH, et al. Major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving apixaban or warfarin: The ARISTOTLE Trial (Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation): Predictors, Characteristics, and Clinical Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2141-7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.549 pmid:24657685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia DA, Lopes RD, Hylek EM. New-onset atrial fibrillation and warfarin initiation: high risk periods and implications for new antithrombotic drugs. Thromb Haemost 2010;104:1099-105. 10.1160/TH10-07-0491 pmid:20886196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White HD, Gruber M, Feyzi J, et al. Comparison of outcomes among patients randomized to warfarin therapy according to anticoagulant control: results from SPORTIF III and V. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:239-45. 10.1001/archinte.167.3.239 pmid:17296878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones M, McEwan P, Morgan CL, Peters JR, Goodfellow J, Currie CJ. Evaluation of the pattern of treatment, level of anticoagulation control, and outcome of treatment with warfarin in patients with non-valvar atrial fibrillation: a record linkage study in a large British population. Heart 2005;91:472-7. 10.1136/hrt.2004.042465 pmid:15772203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prins MH, Lensing AWA, Bauersachs R, et al. EINSTEIN Investigators. Oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism: a pooled analysis of the EINSTEIN-DVT and PE randomized studies. Thromb J 2013;11:21 10.1186/1477-9560-11-21 pmid:24053656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh M, Stewart R, White H. Importance of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1726-31. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu197 pmid:24864078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146-56. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 pmid:11253156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benetos A, Rossignol P, Cherubini A, et al. Polypharmacy in the aging patient: management of hypertension in octogenarians. JAMA 2015;314:170-80. 10.1001/jama.2015.7517 pmid:26172896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary materials