Abstract

Introduction: Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) lead to masticatory muscle pain, jaw movement disability and limitation in mouth opening. Pain is the chief complaint in 90% of the TMD patients which leads to disability and severe socioeconomic costs. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the therapeutic effects of low level laser therapy (LLLT) compared to pharmacotherapy with NSAIDs (naproxen) in myofascial pain disorder syndrome (MPDS).

Methods: In this randomized controlled clinical trial, 40 MPDS patients were divided into two groups. One group received naproxen 500 mg bid for 3 weeks as treatment modality and also had placebo laser sessions. The other group received active laser (diode 810 nm CW) as treatment and placebo drug. Pain intensity was measured by visual analogue scale (VAS) and maximum painless mouth opening was also measured as a functional index every session and at 2 months follow up. Data was collected and analyzed with SPSS software. Independent t test was used to analyze the data. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results: Low level laser caused significant reduction in pain intensity (P < 0.05) and a significant increase in mouth opening. In naproxen group neither pain intensity nor maximum mouth opening had significant improvement. Pain relief, in subjective VAS was observed in third session in LLLT group, but did not occur in naproxen group. Maximum mouth opening increased significantly in laser group compared to the naproxen group from the eighth session.

Conclusion: Treatment with LLLT caused a significant improvement in mouth opening and pain intensity in patients with MPDS. Similar improvement was not observed in naproxen group.

Keywords: Myofascial pain disorder syndrome, Laser therapy, Low-level, Naproxen, Temporomandibular

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) are the major etiology of non-dental pain in the orofacial region, which comprises of signs and symptoms related to masticatory muscles, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) or associated structures.1 The features of TMD are characterized by classically described clinical signs including muscle/TMJ pain, TMJ sounds, restriction, deviation or deflection of mouth opening. 40%-75% of non-patient adults display one sign of temporomandibular disorder during life and approximately 33% report at least one symptom of TMJ dysfunction.1

Unilateral facial pain is the most common symptom reported by patients with temporomandibular disorder. Pain associated with temporomandibular disorder is an important source of disability and causes considerable socioeconomic costs. Mandibular movements are usually limited and actions such as chewing, talking or yawning increase the pain.2

Management of TMD is based mainly on conservative and reversible treatment modalities such as behavioral modification, pharmacotherapy and orthopedic appliances. Approximately 85% to 90% of TMD can be treated with non-invasive, non-surgical and reversible interventions. More aggressive and irreversible therapies such as complex occlusal therapy or surgery should be avoided and limited to few selected cases.3

The most important role of pharmacotherapy in the management of myofascial pain is providing sufficient analgesia in order to break the pain cycle to facilitate functional restoration. Analgesic drugs are an essential part of the primary treatment for TMD related pain and dysfunction.4 The most commonly prescribed agents include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, anxiolytics. NSAIDs have traditionally been the most commonly used drug for pain in the orofacial region.3-5 NSAIDs are known to have multiple actions within the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system, which seem to be related to inhibition of synthesis of prostaglandins, in the large part through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase.4

Naproxen is a propionic acid derivative with a half-life of 12 to 24 hours which allows long lasting pain relief and more compliance of patients. Significant improvement in pain intensity and mandibular range of motion occurred within 3 weeks of treatment with naproxen (500 mg, twice daily) in TMD patients.6,7

Among the wide range of physiotherapy modalities for management of TMD, the use of low level laser therapy (LLLT) has achieved more popularity because of its conservative nature. Also analgesic, regenerative and anti-inflammatory effects of LLLT in the target tissue have been demonstrated.8 Several mechanisms have been proposed for pain reduction and the therapeutic effects of low level lasers, including release of endogenous opioids, enhanced cell respiration and tissue healing, increased vasodilation, increased pain threshold by affecting cellular membrane potential and decreased inflammation possibly due to reduction of prostaglandin E2 and suppression of cyclooxygenase 2 levels.8

LLLT has many advantages such as being well tolerated at any age, painless, aseptic and cost effective. Thus LLLT is almost free of side effects. Nil negative or pathological effects on human body have been reported as side effects of LLLT. Besides, LLLT is important in reducing costs of treatment, as patients have less need for surgical treatment or medicine use during treatment. Moreover, quick improvement observed during treatment has a positive psychological effect especially on patients suffering from chronic symptoms.8,9 Also super pulsed low level laser therapy (SLLLT) which is a new approach increasingly used in medicine has been shown to have several effects in the management of pain. It also has been postulated that SLLLT has been more efficient in the treatment of pain caused by TMJ disorder compared to ibuprofen.10

Controversial results regarding the therapeutic efficacy of LLLT in the management of TMD have been demonstrated by previous studies.8-14 Also there is no comparison between LLLT and pharmacotherapy with naproxen for treating MPDS. The aim of this double blind placebo controlled clinical trial is to investigate the efficacy of LLLT with gallium-aluminum-arsenide (Ga-Al-As) versus pharmacotherapy with naproxen in the treatment of myogenic TMD.

Methods

Forty MPDS patients were selected among patients referred to the department of oral and maxillofacial medicine, School of Dentistry, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences according to the standardized examination/diagnosis procedure based upon the research diagnostic criteria (RDC)/TMD.1 The study included subjects suffering from myofascial pain with/without limited mouth opening. Limited mouth opening was defined as pain-free unassisted mandibular opening of ˂40 mm.7 Subjects who received analgesic or antidepressant medicine or underwent any other form of treatment for TMD were excluded from the study. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and it was registered in the U.S. National Institute of Health (NCT01659372). The purpose of the study was described to each participant and an informed consent was obtained prior to the start of treatment. The cases were randomly divided into LLLT and naproxen groups with 20 patients in each group. Also the patients in laser group received placebo drug and the patients in naproxen group received placebo laser to eliminate the probable psychological effects of laser. All the evaluations were performed by an independent investigator who had been trained to do these procedures beforehand. Neither the patient, nor the evaluator was aware of the group the participant was assigned to. So, the study was conducted in a double blind fashion.

Laser calibration was done before use and the laser probe was disinfected with alcohol before each treatment. The patients and the investigator were required to wear protective glasses. The laser device was a gallium-aluminum-arsenide diode source (Doctor Smile Diode Laser, Italy) with a wavelength of 810 nm and a continuous 0.5 W peak power output beam with 5 mm spot size. The probe was held perpendicularly with a light pressure on the targeted muscle. The masticatory muscles were evaluated bilaterally with firm and constant pressure to define painful areas. Laser group patients received 12 sessions of LLLT according to Table 1.15 For each painful masticatory muscle the laser light was delivered in continuous mode and in contact with a light pressure on tender points diagnosed at the start of treatment. The total amount of irradiation time per painful point was 60 seconds. At the beginning of each session, pain intensity was measured and recorded during palpation of masticatory muscles using a 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS) on which the patients marked their pain intensity, where 0 corresponds to no pain and 10 the worst imaginable pain (0-10, VAS). To measure maximum vertical opening, patients were asked to open their mouth as wide as possible while having no pain. Then, using a digital ruler, vertical distance from incisal edge of the upper central incisor to the labioincisal edge of the opposing lower central incisor was recorded. The data were recorded by an examiner who was unaware of the type of treatment. Laser group also received placebo drug for the first 3 weeks. In naproxen group patients received capsule naproxen (cap) 500 mg twice daily (every 12 hours) for 3 weeks and placebo laser.

Table 1 . Laser Irradiation Protocol .

| Day | Week | |||

| 1st week | 2nd week | 3rd week | 4th week | |

| Saturday | 0.5 W | 0.2 W | 0.3 W | 0.1 W |

| Sunday | 0.4 W | |||

| Monday | 0.3 W | 0.3 W | ||

| Tuesday | 0.2 W | |||

| Wednesday | 0.1 W | 0.4 W | 0.2 W | 0.2 W |

Pain intensity and maximum painless mouth opening were measured each session at the beginning of the session and 2 months after completing the treatment. A minimal of at least 50% reduction in pain intensity was considered as pain relief.16

Mean, median, range and standard deviation (SD) were determined using statistical software SPSS 16 with descriptive analysis. For comparison of averages, independent t test was used after the normal distribution of data. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

All participants completed the study period. Thirty patients (75%) were female and 25% (10 patients) were male. In this study, the mean age of subjects was 36±12.34. Regarding the results of the current study, the most and the least common muscular involvements are related to masseter (75% of cases) and temporal muscles (41% of cases), respectively (masseter ˃ medial pterygoid ˃ lateral pterygoid ˃temporalis). Subjective VAS and pain intensity in each muscle was evaluated and recorded. The mean value of subjective pain intensity in laser group was 7.25±1.51 and in naproxen group was 6.60±1.50. After completion of the treatment, the mean value in laser group decreased to 0.30±0.57, whereas in naproxen group it was 5.24±1.64. In the 2 months follow up the mean VAS in laser group was 0.31±0.58 (Table 2).

Table 2 . Changes in Mean Subjective VAS in Groups in the Whole Treatment Phase and Follow-up .

| Visit | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 3rd Visit | 4th Visit | 5th Visit | 6th visit | 7th Visit | 8th Visit | 9th Visit | 10th Visit | 11th Visit | 12th Visit | Visit in 2 months |

| Mean (laser group) | 7.25±1.51 | 5.65±1.69 | 4.80±1.79 | 4.05±1.84 | 2.75±2.19 | 2.15±2.05 | 1.70±1.65 | 0.75±1.06 | 0.60±0.88 | 0.35±0.74 | 0.35±0.74 | 0.30±0.57 | 0.31±0.58 |

| Mean (naproxen group) | 6.6±1.50 | 6.3±1.46 | 6.05±1.79 | 5.55±1.60 | 5.55±1.60 | 5.20±1.96 | 5.20±1.79 | 5.05±1.60 | 4.9±1.71 | 5.05±1.89 | 5.41±1.60 | 5.24±1.64 | |

| P (2 tailed) | 0.181 | 0.170 | 0.034 | 0.009 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 |

The initial pain value of masseter muscle in laser group was 7.61±1.04, which decreased significantly to 0.3±0.63 in laser group (P<0.05). In naproxen group it was 7.05±1.51, which did not show any significant improvement during the treatment. Among the groups, significant pain reduction in laser group started in the third visit, after the second irradiation (Table 3).

Table 3 . Changes in Mean VAS in Groups in Each Muscle During the Whole Treatment Phase and Follow-up .

| 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 3rd Visit | 4th Visit | 5th Visit | 6th Visit | 7th Visit | 8th Visit | 9th Visit | 10th Visit | 11th Visit | 12th Visit | Follow | |

| Masseter | |||||||||||||

| Mean (laser group) | 7.61 ± 1.04 | 5.69 ± 1.75 | 4.69±2.01 | 4.15 ± 1.86 | 3.15 ± 1.86 | 2.84±1.77 | 2.00 ± 1.82 | 1.46 ± 1.50 | 1.07 ± 1.25 | 0.69 ± 0.94 | 0.53 ± 0.87 | 0.30 ± 0.63 | 0.30 ± 0.63 |

| Mean (naproxen group) | 7.05 ± 1.51 | 6.70 ± 1.57 | 6.29±1.57 | 5.88 ± 1.53 | 5.70 ± 1.53 | 5.52±1.69 | 5.52 ± 1.66 | 5.70 ± 1.53 | 5.70 ± 1.53 | 5.76 ± 1.60 | 5.76 ± 1.56 | 5.82 ± 1.59 | |

| P (2 tailed) | 0.268 | 0.107 | 0.021 | 0.009 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 |

| Temporalis | |||||||||||||

| Mean (laser group) | 7.61 ± 1.04 | 5.69 ± 1.75 | 4.69±2.01 | 4.15 ± 1.86 | 3.15 ± 1.86 | 2.84±1.77 | 2.00 ± 1.82 | 1.46 ± 1.50 | 1.07 ± 1.25 | 0.69 ± 0.94 | 0.53 ± 0.87 | 0.30 ± 0.63 | 0.30 ± 0.63 |

| Mean (naproxen group) | 7.05±1.51 | 6.70 ± 1.57 | 6.29±1.57 | 5.88 ± 1.53 | 5.70 ± 1.53 | 5.52±1.69 | 5.52 ± 1.66 | 5.70 ± 1.53 | 5.70 ± 1.53 | 5.76 ± 1.60 | 5.76 ± 1.56 | 5.82 ± 1.59 | |

| P (2 tailed) | 0.268 | 0.107 | 0.021 | 0.009 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 |

| Medial Pterygoid | |||||||||||||

| Mean (laser group) | 7.30 ± 0.39 | 6.69 ± 0.54 | 5.33±0.46 | 4.30 ± 0.51 | 3.30 ± 0.47 | 2.38±0.48 | 1.38 ± 0.43 | 0.84 ± 0.38 | 0.69 ± 0.32 | 0.46 ± 0.21 | 0.23 ± 0.12 | 0.23 ± 0.12 | 0.23 ± 0.12 |

| Mean (naproxen group) | 5.9 ± 0.46 | 5.2 ± 0.46 | 5.08±0.46 | 4.75 ± 0.46 | 4.50 ± 0.50 | 4.25±0.50 | 4.33 ± 0.48 | 4.50 ± 0.46 | 4.58 ± 0.46 | 4.58 ± 0.49 | 4.75 ± 0.49 | 4.91 ± 0.48 | |

| P (2 tailed) | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.015 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 |

| Lateral Ptreygoid | |||||||||||||

| Mean (laser group) | 6.33 ± 0.69 | 5.75 ± 0.59 | 4.50±0.51 | 3.58 ± 0.49 | 2.58 ± 0.59 | 2.41±0.59 | 1.41±0.43 | 0.75 ± 0.30 | 0.83 ± 0.32 | 0.41± | 0.33±0.19 | 0.33±0.18 | 0.50±0.19 |

| Mean (naproxen group) | 5.70 ± 0.33 | 5.20 ± 0.32 | 4.90±0.31 | 4.80 ± 0.32 | 4.70 ± 0.33 | 4.30±0.39 | 4.20±0.32 | 4.40 ± 0.304 | 4.50 ± 0.37 | 4.70±0.36 | 4.90±0.37 | 4.90±0.37 | |

| P (2 tailed) | 0.406 | 0.451 | 0.535 | 0.065 | 0.008 | 0.020 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 |

Significant reduction in pain intensity of temporalis, medial pterygoid and lateral pterygoid muscles was also observed in laser group (P<0.05). In temporalis muscle, significant pain reduction was observed in the fourth session in laser group. Mean pain intensity in the initial session in temporalis muscle was 7.25±1.89, and in the follow up at 2 months, the VAS was 0. While, for the naproxen group, no significant pain reduction was observed (Table 3).

Significant pain reduction in the medial pterygoid muscle in laser group started from the sixth session, which in Lateral pterygoid started from the fifth session (P<0.05) (Table 3).

Maximum painless mouth opening in laser group was 31.63±7.35, which improved to 42.26±4.56 after completion of the treatment. It was 33.95±3.85 in naproxen group, which at the end of treatment was 34.60±3.85 and did not show any significant improvement. Significant improvement in mouth opening started from the eighth session (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed between the groups until the eighth session (Table 4).

Table 4 . Changes in Maximum Painless Mouth Opening During the Treatment and Follow-up .

| Visit | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 3rd Visit | 4th Visit | 5th Visit | 6th visit | 7th Visit | 8th Visit | 9th Visit | 10th Visit | 11th Visit | 12th Visit | Visit in 2 months |

| Mean (laser group) | 31.63±7.35 | 33.05±5.94 | 33.94±5.63 | 35.84±5.31 | 36.68±5.51 | 36.10±5.16 | 39.00±8.84 | 39.52±5.38 | 40.42±4.92 | 41.00±4.71 | 41.89±4.28 | 42.26±4.56 | 42.26±4.78 |

| Mean (naproxen group) | 33.95±3.85 | 34.05±3.83 | 34.45±3.97 | 34.55±3.95 | 34.55±3.85 | 34.70±3.86 | 34.75±3.87 | 34.80±3.92 | 34.85±3.75 | 34.80±3.92 | 34.75±3.87 | 34.60±3.85 | |

| P (2 tailed) | 0.222 | 0.535 | 0.748 | 0.792 | 0.400 | 0.181 | 0.536 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 000 | 000 | 000 | 000 |

After completing the study, the subjects in the naproxen and placebo laser group tended to continue treatment received or another form of therapy for TMD (occlusal appliance therapy, laser therapy).

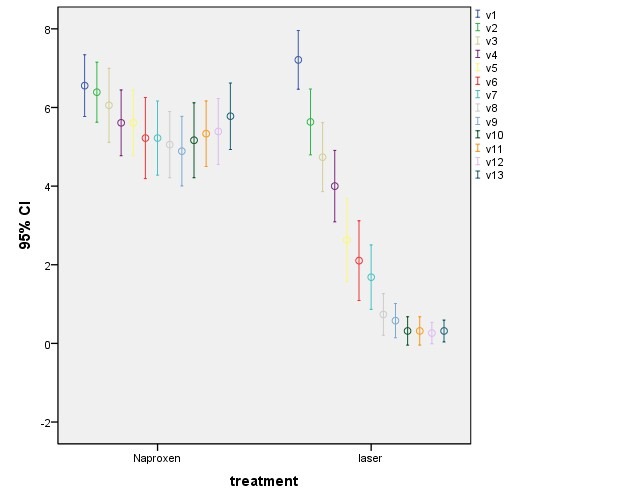

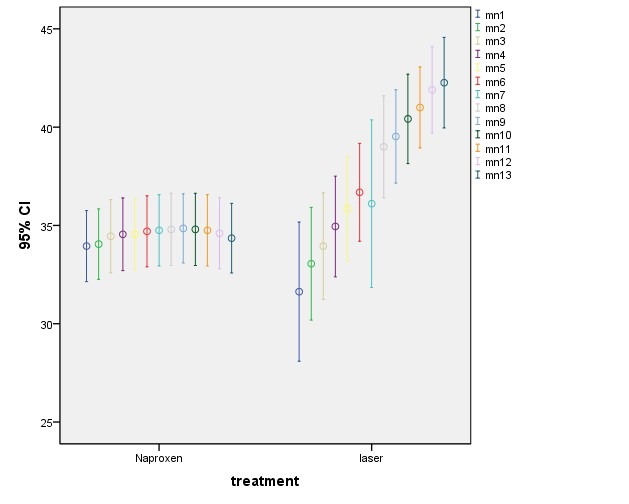

Figure 1 demonstrates VAS changes during treatment. Figure 2 shows changes in mouth opening during treatment. Comparing Figures 1 and 2 indicates improvement in mouth opening while reduction in pain intensity occurs. As shown in the figures, a remarkable decrease in pain intensity and a significant improvement in mouth opening was observed in laser group. While reduction in pain intensity was observed, mouth opening significantly increased.

Figure 1 .

VAS Score Changes During the Whole Phase of Treatment and Follow-up in Laser and Naproxen Groups.

Figure 2 .

Maximum Mouth Opening Changes During the Whole Phase of Treatment and Follow-up in Laser and Naproxen Groups (increase in mouth opening occurred along with reduction in pain intensity in laser group).

Discussion

LLLT is a non-invasive, rapid, safe and non-pharmaceutical treatment method that may be beneficial for patients with TMD.9-12 Thus the aim of this study was to evaluate whether LLLT could reduce pain intensity and improve mouth opening in patients with MPDS.

Similar to the results of various epidemiologic and clinical studies, the occurrence of MPDS in females (75%) was higher than males (15%). Although there are various reasons for sex-related differences in the prevalence of TMD, one reason to explain the increased occurrence of this disorder in women has been suggested to be the female sex hormone estrogen. Also, since females are more prone to psychological disorders and they have low tolerance to pain, these results might be reasonable.5,17 The results of this study are in agreement with those of other investigators including Cairns,5 Martins-Júnior et al18 and Mortazavi et al.19

In this study, the mean age of subjects was 36 ± 12.34. According to the results of the current study and other investigations achieved by Lipton et al20 and Glass & Glaros,21 the most common age for onset of this syndrome is between 20-40 years old. Also Minghelli et al demonstrated a range of 6%-68% occurrence of TMD in children and adolescents, which could be triggered or aggravated by emotional stress.22

95.86% pain reduction occurred in laser group, while the pain did not recur in the follow-up period. Analgesic effects of laser therapy in the treatment of muscular and joint dysfunction are due to an increase of beta endorphin level, pain discharge threshold, lymphatic flow, blood supply and muscle relaxation along with decrease of bradykinin and histamine release with edema.8-10 In naproxen group 20.6% pain reduction was observed. Laser therapy has been consistently shown to be a valid alternative to NSAIDs. In some studies, results show that LLLT doses of 3 J can significantly reduce inflammation, produce less cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression, and produce less edema formation than their non-irradiated counterparts and the authors went on to say that laser therapy may in fact have potential to become a new and safer nondrug alternative to NSAIDs. Laser therapy is also able to increase the number of newly formed vessels. In musculoskeletal diseases the aim is usually to increase angiogenesis which will aid in the healing process. Laser therapy has been shown to increase angiogenesis and blood flow by promoting new blood vessel capillary budding and increased collateral circulation.23-26

Regarding tenderness (pain on palpation) of masticatory muscles there was a significant reduction in pain symptoms in laser group. While in the naproxen group there was no significant reduction in pain symptoms, nor in maximum painless mouth opening. The positive outcome of LLLT was also demonstrated in previous studies by Salmos-Brito and Menezes9 (gallium–aluminum–arsenide; λ=830 nm, P=40 mW, CW, ED08 J/cm2), Ahrari and Madani8 (pulsed 810 nm, average power 50 mW, peak power 80 W, 1500 Hz, 120 seconds, 6 J, and 3.4 J/cm2 per point), Mazzetto et al11 (780 nm, 70 mW , 89.7 J/cm2), Shirani et al12 (660 nm, 0 Hz, 17. 3 mW, 6.2 J/cm2), who all found significant reduction in pain intensity of TMD patients with LLLT. The placebo effect of LLLT was not demonstrated in this study because the naproxen group did not experience a significant relief in clinical symptoms. This finding correlates with the results of previous authors who reported a significant pain relief for TMD patients treated with active laser, but not for the placebo application. The findings of this study are, however, in contrast with Emshoff et al14 (632.8 nm, 30 mW, 1.5 J/cm2), Carrasco et al13 (780 nm, 50/60/70 J/cm2) and da Cunha et al25 (830 nm, 500 Mw, 100 J/cm2), who reported a significant reduction of pain intensity in both laser and placebo groups, suggesting that improvement was mostly due to the placebo effect of laser administration.27

Similar to the results of our study Marini et al also postulated that pain severity and mandibular function improved in all patients who received SLLLT and it has been more efficient in the treatment of pain caused by TMJ disorder compared to ibuprofen.10

In this research a significant improvement was observed in maximum painless mouth opening in laser group. Results demonstrate 33.60% increase in mouth opening in laser group which started from the eighth session. It means that the functional improvement and the objective functional parameters for the patients occurred later than the decrease in pain intensity which coordinates with Mazzetto et al.11 In naproxen group no significant increase in mouth opening was observed.

LLLT can be considered as a suitable alternative for conventional treatments of TMD, which improves the treatment outcomes by reducing the painful clinical symptoms and allowing the clinician to remove the underlying etiological factors.8,9 Considering the conservative nature of this therapy, future studies and long term follow ups are needed to determine the efficacy of LLLT in the management of patients with TMDs of different etiologies. The combined effect of other available treatment modalities with LLLT and the possible synergism or interaction between them should also be investigated in future studies.

Conclusion

Treatment with a low level Diode laser 810 nm (Ga-Al-As) resulted in significant improvement of mouth opening and pain intensity in MPDS patients. LLLT can be considered as a suitable, noninvasive treatment alternative for myogenous pain. Also the stability of the laser treatment outcomes signifies the preference of laser treatment for MPDS patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are greatly thankful to the staff members of laser department of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.

Please cite this article as follows: Khalighi HR, Mortazavi H, Mojahedi SM, Azari-Marhabi S, Moradi Abbasabadi F. Low level laser therapy versus pharmacotherapy in improving myofascial pain disorder syndrome. J Lasers Med Sci. 2016;7(1):45-50. doi:10.15171/jlms.2016.10.

References

- 1.Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112(4):453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbosa TS, Leme MS, Castelo PM. Evaluating oral health-related quality of life measure for children and preadolescents with temporomandibular disorder. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;12:9–32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scrivani SJ, Keith DA, Kaban LB. Temporomandibular disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2693–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argoff CE. Pharmacologic management of chronic pain. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2002;102:S21–S217. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2010.23.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns BE. Pathophysiology of TMD pain--basic mechanisms and their implications for pharmacotherapy. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:391–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ta LE, Dionne RA. Treatment of painful temporomandibular joints with a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor: a randomized placebo-controlled comparison of celecoxib to naproxen. Pain. 2004;111(1-2):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greenberg M, Glick M, Ship J. Burkett’s Oral Medicine.11th ed. BC Decker Inc; 2008:235-246.

- 8.Ahrari F, Madani AS. The efficacy of low-level laser therapy for the treatment of myogenous temporomandibular joint disorder. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(2):551–557. doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salmos-Brito JA, Menezes RF. Evaluation of low-level laser therapy in patients with acute and chronic temporomandibular disorders. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28(1):57–64. doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marini I, Gatto MR, Bonetti GA. Effects of superpulsed low-level laser therapy on temporomandibular joint pain. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(7):611–6. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e0190d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzetto MO, Hotta TH, Pizzo RC. Measurements of jaw movements and TMJ pain intensity in patients treated with GaAlAs laser. Braz Dent. 2010;21(4):356–360. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402010000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirani AM, Gutknecht N, Taghizadeh M. Low-level laser therapy and myofacial pain dysfunction syndrome: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2009;24:715–720. doi: 10.1007/s10103-008-0624-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrasco TG, Guerisoli LD, Guerisoli DM. Evaluation of low intensity laser therapy in myofascial pain syndrome. Cranio. 2009;27:243–247. doi: 10.1179/crn.2009.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emshoff R, Bösch R, Pümpel E. Low-level laser therapy for treatment of temporomandibular joint pain: a double-blind and placebo-controlled trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hode TJ. Clinical practice and scientific background. Tallinn, Estonia: Prima Books; 2002.

- 16.Seres JL. The fallacy of using 50% pain relief as the standard for satisfactory pain treatment outcome, J Pain. 1999;8:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okeson JP. Management of temporomandibular disorder and occlusion. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2008:2-375.

- 18.Martins-Júnior RL, Palma AJ, Marquardt EJ, Gondin TM, Kerber Fde C. Temporomandibular disorders: a report of 124 patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2010;14:071–078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortazavi H, Javadzadeh A, Delavarian Z, Zare Mahmoodabadi R. Myofascial Pain Dysfunction Syndrome. Iranian J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;22:61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipton JA, Ship JA, Larch-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:115–121. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glass EG, Glaros AG. Health service research on TMD. In: Sessle BJ, Bryant PS, Dionne RA, editors. Temporomandibular disorder and related pain conditions. Progress in pain research and management. Seattle: IASP; 1995:249-254.

- 22.Minghelli B, Cardoso I, Porfírio M. et al. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder in children and adolescents from public schools in southern Portugal. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6(3):126–132. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.128474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh YL, Chou LW, Chang PL. Low-level laser therapy alleviates neuropathic pain and promotes function recovery in rats with chronic constriction injury-possible involvements in hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) J Comp Neurol. 2012;520(13):2903–2916. doi: 10.1002/cne.23072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcos RL, Leal Junior EC, Messias Fde M. Infrared (810 nm) low-level laser therapy in rat Achilles tendinitis: a consistent alternative to drugs. Photochem Photobiol. 2011;87(6):1447–1452. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Cunha LA, Firoozmand LM, da Silva AP. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy in the treatment of temporomandibular disorder. Int Dent J. 2008;58:213–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herranz-Aparicio J, Vázquez-Delgado E, Arnabat- Domínguez J, España-Tost A, Gay-Escoda C. The use of low level laser therapy in the treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders Review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18(4):e603–e612. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melis M, Di Giosia M, Zawawi KH. Low level laser therapy for the treatment of temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Cranio. 2012;30:304–312. doi: 10.1179/crn.2012.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]