Abstract

BACKGROUND

Recent evidence suggests that chemokine receptor CXCR4 regulates vascular α1-adrenergic receptor function and that the noncognate CXCR4 agonist ubiquitin has therapeutic potential after trauma/hemorrhage. Pharmacologic properties of ubiquitin in large animal trauma models, however, are poorly characterized. Thus, the aims of the present study were to determine the effects of CXCR4 modulation on resuscitation requirements after polytrauma, to assess whether ubiquitin influences survival times after lethal polytrauma-hemorrhage, and to characterize its dose-effect profile in porcine models.

METHODS

Anesthetized pigs underwent polytrauma (PT, femur fractures/lung contusion) alone (Series 1) or PT/hemorrhage (PT/H) to a mean arterial blood pressure of 30 mmHg with subsequent fluid resuscitation (Series 2 and 3) or 40% blood volume hemorrhage within 15 minutes followed by 2.5% blood volume hemorrhage every 15 minutes without fluid resuscitation (Series 4). In Series 1, ubiquitin (175 and 350 nmol/kg), AMD3100 (CXCR4 antagonist, 350 nmol/kg), or vehicle treatment 60 minutes after PT was performed. In Series 2, ubiquitin (175, 875, and 1,750 nmol/kg) or vehicle treatment 60 minutes after PT/H was performed. In Series 3, ubiquitin (175 and 875 nmol/kg) or vehicle treatment at 60 and 180 minutes after PT/H was performed. In Series 4, ubiquitin (875 nmol/kg) or vehicle treatment 30 minutes after hemorrhage was performed.

RESULTS

In Series 1, resuscitation fluid requirements were significantly reduced by 40% with 350-nmol/kg ubiquitin and increased by 25% with AMD3100. In Series 2, median survival time was 190 minutes with vehicle, 260 minutes with 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin, and longer than 420 minutes with 875-nmol/kg and 1,750-nmol/kg ubiquitin (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle). In Series 3, median survival time was 288 minutes with vehicle and 336 minutes and longer than 420 minutes (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle) with 175-nmol/kg and 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin, respectively. In Series 4, median survival time was 147.5 minutes and 150 minutes with vehicle and ubiquitin, respectively (p > 0.05).

CONCLUSION

These findings further suggest CXCR4 as a drug target after PT/H. Ubiquitin treatment reduces resuscitation fluid requirements and provides survival benefits after PT/H. The pharmacological effects of ubiquitin treatment occur dose dependently.

Keywords: Ubiquitin, AMD3100, survival, cardiovascular collapse, resuscitation

In the United States, trauma is the fifth leading cause of death in the overall population and the leading cause of death among those aged 5 years to 44 years.1 Hemorrhagic shock is the major cause of potentially preventable death after accidental injuries. Hemorrhagic shock accounts for more than 35% of prehospital deaths and more than 40% of deaths within the first 24 hours in trauma patients.2 Depending on the magnitude of blood loss, hemorrhage results in compensated shock, which can progress toward decompensated and subsequently irreversible shock, leading to cardiovascular collapse and death. During compensated and decompensated hemorrhagic shock, fluid resuscitation and surgical/interventional bleeding control can normalize hemodynamics. Irreversible shock, however, remains unresponsive to treatment. Whereas the mechanisms responsible for progression from decompensated to irreversible shock are unknown, loss of vascular tone is characteristic for cardiovascular collapse during hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation.3 The current treatment of hemorrhagic shock is limited to fluid resuscitation, surgical/interventional bleeding control, and blood component substitution once the patient arrives in the hospital. Although pressure-support resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock has been discussed as a possible strategy to improve outcomes,4–6 drugs that increase shock tolerance, stabilize cardiovascular function, and prolong survival are currently not available.

Recent evidence suggests that chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 contributes to the regulation of cardiovascular function and modulates vascular reactivity through the formation of heteromeric receptor complexes with α1-adrenergic receptors on the cell surface of vascular smooth muscle cells.7,8 Moreover, several lines of evidence from preclinical studies point toward CXCR4 as a pharmacologic target to modulate blood pressure and hemodynamic stability. The CXCR4 antagonists AMD3100 and AMD3465 have been reported to reduce blood pressures in models of hypertension and to reduce hemodynamic stability during resuscitation from trauma and hemorrhage.7,9–12 Treatment with a peptide analog of the cognate CXCR4 agonist CXCL12 (SDF-1α) and with the noncognate CXCR4 agonist ubiquitin stabilized hemodynamics and prolonged survival in sepsis models,13,14 and ubiquitin treatment stabilized hemodynamics and reduced systemic fluid requirements in various models of nonlethal traumatic/hemorrhagic shock.7,11,15–17 The effects of CXCR4 blockade after polytrauma in large animal models, however, are unknown, and information on the dose-effect relationship of exogenous ubiquitin is limited. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether the finding that ubiquitin treatment prolonged survival in lethal hemorrhagic shock in rats translates from rodent models to large animal polytrauma/hemorrhage models.7 Because such data are essential prerequisites to establish CXCR4 as a pharmacologic target after trauma, we used porcine polytrauma/hemorrhage models to evaluate how pharmacologic CXCR4 modulation affects resuscitation fluid requirements, to characterize the dose-effect relationship for ubiquitin, and to assess whether ubiquitin treatment could provide a survival benefit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Protocol

All procedures were performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Loyola IACUC and the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command ACURO.

Male and female Yorkshire pigs (body weight, 26–40 kg) were fasted overnight. Intramuscular ketamine (10 mg/kg) and xylazine (1 mg/kg) were administered for induction of anesthesia. Peripheral intravenous (IV) access was obtained for continuous infusion of ketamine 10 mg/kg per hour, xylazine 0.25 mg/kg per hour, and fentanyl 50 μg/kg per hour for maintenance of anesthesia throughout the experiment. Orotracheal intubation was performed using a 7.0-mm internal diameter cuffed endotracheal tubes (Teleflex Medical, Arlington Heights, IL) under direct laryngoscopy. Animals were mechanically ventilated (Evita XL, Draeger Medical, Telford, PA) with intermittent mandatory ventilation adjusted to tidal volumes of 12 mL/kg at 10 to 20 breaths per minute to maintain a partial pressure of CO2 (Pco2) between 35 mm Hg and 45 mm Hg. The fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) was 0.4, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) was 5 mm Hg, except where otherwise noted. Core body temperature was maintained using conductive warming blankets. A central venous catheter (Triple-Lumen Catheter, Teleflex Medical) was placed in the external jugular vein for administration of fluids, anesthesia, and continuous monitoring of central venous pressure. The ipsilateral carotid artery was cannulated for hemorrhage and continuous measurement of mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) with a 14-gauge angiocatheter. Electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, capnography (Evita XL Capnography module, Draeger Medical), and body temperature were monitored continuously. After stable baseline conditions (at least 30 minutes after instrumentation) were achieved, animals were subjected to polytrauma (t = 0 minute, bilateral open femur fractures plus lung contusion), as described previously.11,17–19

In brief, injuries were produced with a captive bolt gun (Karl Schermer, Ettlingen, Germany), modified with exchangeable mushroom shaped metal heads (1- and 2.5-in diameter). The bolt gun with the small metal head was placed vertically against the femur and fired while the animal was in supine position and the leg was extended. The metal head perforated the skin and produced a second-degree complex open femur fracture without injury of major vessels. After both femurs had been fractured, the small metal head was exchanged for the large metal head, and the bolt gun was fired against the right chest wall in the midaxillary line at the level of the fourth intercostal space with a 45-degree cephalad trajectory. As confirmed by necropsy, this resulted in lung contusion covering approximately 20% to 30% of the right lung without producing hemothoraces/pneumothoraces or rib fractures, which is consistent with our previous observations in this injury model.11,17,18 All injuries were produced within 5 minutes. Based on an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score of 3 for the extremity trauma and 3 to 4 for the chest trauma, the estimated Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 18 to 25.20

To simulate a shock period, animals were ventilated with an FIO2 of 0.21 and a PEEP of 0 mm Hg, and no resuscitation was allowed other than the minimum amount of lactated Ringer’s solution (LR) required for the delivery of anesthesia. Hemorrhage was performed passively by opening of the arterial line. To simulate typical human resuscitation regimens during prehospital emergency medical services (EMS), ventilation was adjusted to an FIO2 of 1.0 and a PEEP of 5 mm Hg, and resuscitation to a MAP of 70 mm Hg was performed with warmed LR in IV boluses of 500 mL until the MAP reached 70 mm Hg. To simulate in-hospital resuscitation following the EMS period, animals were ventilated with a PEEP of 5 cm H2O and an FIO2 of 0.4, and resuscitation was performed continuously to maintain a MAP of at least 70 mm Hg. At the conclusion of the experiment (t = 420 minutes) or until the time of death (defined as lack of pulse pressure or asystole), a mixture of saturated potassium chloride was infused via the central venous catheter for euthanasia while the animal was under general anesthesia. All experiments were performed randomized and blinded. The dosing of ubiquitin and AMD3100 was selected based on our previous studies.7,11,15–17 The following experimental series were performed:

Series 1: Blunt Polytrauma—Single-Dose Treatment

After injury and a 60-minute shock period, an EMS period was simulated from t = 60 minutes to t = 120 minutes, followed by simulated in-hospital resuscitation for up to 420 minutes. All drug treatments were administered intravenously at the end of the shock period (t = 60 minutes) in a total volume of 500-mL LR. The following treatments were performed: (1) vehicle (n = 7, LR only), (2) 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 7), (3) 350-nmol/kg ubiquitin treatment (n = 5), and (4) 350-nmol/kg AMD3100 (n = 8).

Series 2: Blunt Polytrauma Plus Hemorrhage—Single-Dose Treatment

After injury, animals were hemorrhaged to a MAP of 30 mm Hg for 60 minutes (shock period). At t = 60 minutes, the experimental protocol was same as that in Series 1, except that FIO2 was 0.21 during simulated in-hospital resuscitation. The following treatments were performed: (1) vehicle (LR only, n = 6), (2) 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 6), (3) 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 6), and (4) 1.75-μmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 6).

Series 3: Blunt Polytrauma Plus Hemorrhage—Double-Dose Treatment

The experimental protocol was same as that as in Series 2, except that drugs were administered at t = 60 minutes and t = 180 minutes. The following treatments were performed: (1) vehicle (LR only, n = 12), (2) 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 4), and (3) 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 10).

Series 4: Continuous Hemorrhage, No Fluid Resuscitation—Single-Dose Treatment

Animals underwent 40% blood volume hemorrhage within 15 minutes. At t = 15 minutes, 250 mL of LR (vehicle, n = 8: n = 5 with polytrauma and n = 3 without polytrauma) or 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 5: n = 3 with polytrauma and n = 2 without polytrauma) in 250 mL of LR were administered as a single IV bolus injection. At t = 30 minutes and every 15 minutes thereafter, 2% to 3% of BV were hemorrhaged until death. Animals were ventilated with an FIO2 of 0.21 and a PEEP of 0 cm H2O throughout the experiment. As survival times were similar between animals subjected to polytrauma plus continuous hemorrhage or continuous hemorrhage alone, groups were combined to reduce the number of animal experiments.

All solutions were tested for endotoxin contamination using the Toxin Sensor Chromogenic LAL Endotoxin Assay Kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The endotoxin concentrations in the solutions were less than 0.05 EU/mL, which are suitable for parenteral use in humans.

Blood Gas Analyses and Routine Laboratory Parameters

Arterial blood was sampled every 15 minutes for the first hour after injury, followed by 30-minute intervals. Arterial blood was collected in lithium heparin tubes (APP Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL) and used for blood gas analyses, analyses of routine laboratory parameters, and complete blood cell counts. Plasma was stored at −80°C until further analyses. Measurements of pH, Pco2, Po2, hemoglobin, sodium, potassium, chloride, glucose, lactate, and bicarbonate were performed using a blood gas analyzer (Stat Profile pHOx Plus L, Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA).

Complete Blood Counts

Heparinized blood samples were used for the analysis of complete blood count on a veterinary hematology analyzer (HemaTrue, Heska, Loveland, CO).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays

Ubiquitin plasma concentrations were measured with an indirect competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as described previously.15,21 CXCL12 plasma concentrations were measured using a DuoSet ELISA Development kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), as recommended by the manufacturer. Measurements were performed after all animal experiments had been completed.

Data and Statistical Analyses

Data are described as mean ± SEM. The plasma elimination half-life of ubiquitin (t1/2) was calculated as described.15 Data were analyzed with two-way repeated-measures (mixed model) analysis of variance and Bonferroni post hoc tests to correct for multiple testing. To account for dropouts, the sample size was adjusted after each death. Graphs show only data from animals that are alive at each time point. Survival was plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival between groups was compared with the log-rank test. All data were analyzed using the GraphPad-Prism 6 software. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Series 1: Blunt Polytrauma—Single-Dose Treatment

To assess the effects of pharmacologic CXCR4 modulation on resuscitation fluid requirements after polytrauma, pigs were treated with ubiquitin or with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100. There were no statistically significant differences in any of the measured parameters at baseline among the groups. The ubiquitin plasma concentrations in the various experimental groups are shown in Figure 1A. Endogenous ubiquitin plasma concentrations averaged 497 ± 41 ng/mL at baseline and increased to 760 ± 142 ng/mL at the end of the shock period before drug administration. Ubiquitin plasma concentrations decreased to baseline levels in animals after vehicle or AMD3100 treatment and subsequent fluid resuscitation. After ubiquitin treatment, plasma levels increased to 5,161 ± 554 ng/mL and 8,455 ± 574 ng/mL at t = 90 minutes in animals treated with 175 nmol/kg and 350 nmol/kg, respectively. The plasma half-life of ubiquitin was 0.96 hour after treatment with 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin and 0.91 hour after treatment with 350-nmol/kg ubiquitin. The plasma levels of the cognate CXCR4 agonist CXCL12 are shown in Figure 1B. While there were no significant changes of plasma CXCL12 levels after vehicle and ubiquitin treatment, CXCL12 plasma levels increased fivefold within 60 minutes after AMD3100 treatment and decreased thereafter.

Figure 1.

Ubiquitin and CXCL12 plasma levels after polytrauma. The arrows indicate the time points of polytrauma and drug administration. Shock, shock period; EMS: simulated prehospital emergency medical service period; Resuscitation: simulated in-hospital intensive care unit (ICU) resuscitation period. Open circles, vehicle; light gray squares, 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin; dark gray squares, 350-nmol/kg ubiquitin; gray triangles, 350-nmol/kg AMD3100. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 4–7 per group. A, Ubiquitin plasma concentrations (ng/mL). B, CXCL12 plasma concentrations (pg/mL).

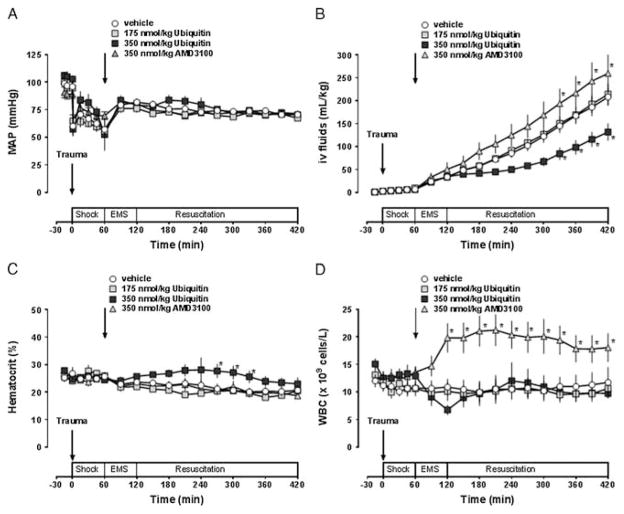

All animals could be resuscitated to the target MAP of 70 mm Hg (Fig. 2A). The systemic fluid requirements to maintain MAP at the target value were 208 ± 19 mL/kg with vehicle treatment (Fig. 2B). Systemic fluid requirements to maintain MAP at 70 mm Hg were 214 ± 23 mL/kg with 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin (p > 0.05 vs. vehicle) and to 132 ± 19 mL/kg with 350-nmol/kg ubiquitin (p < 0.05). In contrast, systemic fluid requirements to maintain MAP at 70 mm Hg were increased after AMD3100 treatment, when compared with vehicle-treated animals (260 ± 44 mL/kg, p < 0.05 vs. vehicle). Hematocrit values showed only transient differences between vehicle and 350-nmol/kg ubiquitin–treated animals between t = 270 minutes and t = 330 minutes (Fig. 2C). Whereas leukocyte counts remained constant with vehicle and ubiquitin treatment, leukocyte counts increased within 1 hour after AMD3100 treatment and remained elevated until the end of the observation period (Fig. 2D). There were no significant differences in any other of the physiologic parameters that were measured among the groups (not shown).

Figure 2.

Pharmacologic CXCR4 modulation after polytrauma. The arrows indicate the time points of polytrauma and drug administration. Shock, shock period; EMS, simulated prehospital emergency medical service period; Resuscitation, simulated in-hospital ICU resuscitation period. Open circles, vehicle; light gray squares, 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin; dark gray squares, 350-nmol/kg ubiquitin; gray triangles, 350-nmol/kg AMD3100. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 5–8 per group. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle. A, MAP (mm Hg). B, Fluid requirements to maintain MAP at 70 mm Hg (mL/kg). C, Hematocrit values (%). D, White blood cell counts (WBC, ×109 cells/L).

Series 2: Blunt Polytrauma Plus Hemorrhage—Single-Dose Treatment

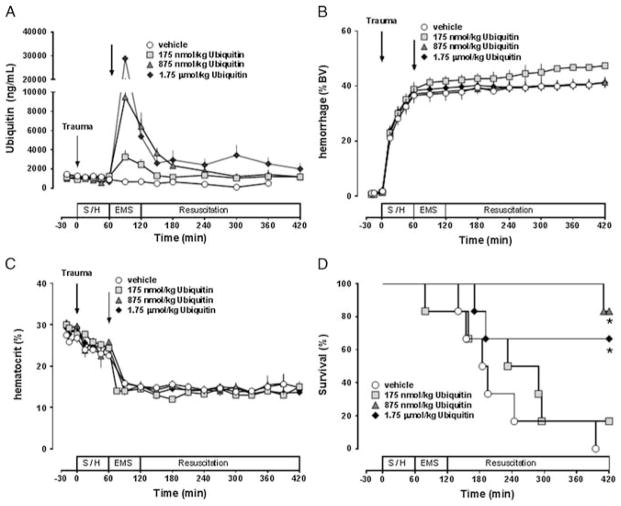

To determine whether ubiquitin treatment could provide a survival benefit in a model with significant mortality and to further define the dose-effect relationship of its pharmacologic effects, we then combined polytrauma with subsequent hemorrhage to a MAP of 30 mm Hg for 60 minutes and treated animals with vehicle or with three different doses of ubiquitin. There were no statistically significant differences in any of the measured parameters at baseline among the groups. Figure 3A shows the ubiquitin plasma concentrations in the various experimental groups. At t = 90 minutes, ubiquitin plasma concentrations averaged 3,240 ± 694 ng/mL, 9,495 ± 1,976 ng/mL, and 28.8 ± 12.2 μg/mL after administration of 175-ng/mL, 875-ng/mL, and 1.75-μg/mL ubiquitin, respectively. The determined plasma half-lives of ubiquitin were 1.5 hours with 175-ng/mL ubiquitin, 1.1 hours with 875-ng/mL ubiquitin, and 0.71 hour with 1.75-μg/mL ubiquitin. Hemorrhage volumes and hematocrit values were comparable among all treatment groups (Fig. 3B and C). One animal after treatment with 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin died during the EMS phase at t = 79 minutes. All other animals could be resuscitated to the target MAP of 70 mm Hg during the EMS phase. While animals after vehicle treatment required 176 ± 16 mL/kg of IV fluids until t = 120 minutes to achieve this resuscitation end point, resuscitation fluid requirements were 157 ± 16 mL/kg after treatment with 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin (p > 0.05 vs. vehicle), and 121 ± 8 mL/kg and 108 ± 14 mL/kg after treatment with 875-nmol/kg and 1.75-μg/kg ubiquitin, respectively (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle for both). Subsequent mortality occurred because of cardiovascular collapse with rapid decreases in blood pressures as well as loss of pulse pressures and asystole during continued fluid resuscitation (Fig. 3D). In animals after vehicle treatment, median survival time was 190 minutes. None of the vehicle-treated animals survived the observation period. After treatment with 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin, median survival time was 260.5 minutes with one of six animals surviving the observation period of 420 minutes (p > 0.05 vs. vehicle). After treatment with 875-nmol/kg and 1.75-μmol/kg ubiquitin, median survival times were longer than 420 minutes with five and four of six animals surviving the observation period, respectively (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle for both; hazard ratio [95% confidence interval]: vehicle/875-nmol/kg ubiquitin, 22 [4–125]; vehicle/1.75-μmol/kg ubiquitin, 4.7 [1.1–20]).

Figure 3.

Ubiquitin treatment after lethal polytrauma and hemorrhage—single dosing. The arrows indicate the time points of polytrauma and drug administration. Shock, shock period; EMS, simulated prehospital emergency medical service period; Resuscitation, simulated in-hospital ICU resuscitation period. Open circles, vehicle; light gray squares, 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin; dark gray triangles: 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin; dark gray diamonds, 1,750-nmol/kg ubiquitin. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 6 per group. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle. A, Ubiquitin plasma concentrations (ng/mL). B, Hemorrhage volume in % of blood volume (BV). C, Hematocrit values (%). D, Kaplan-Meier survival plot.

Series 3: Blunt Polytrauma Plus Hemorrhage—Double-Dose Treatment

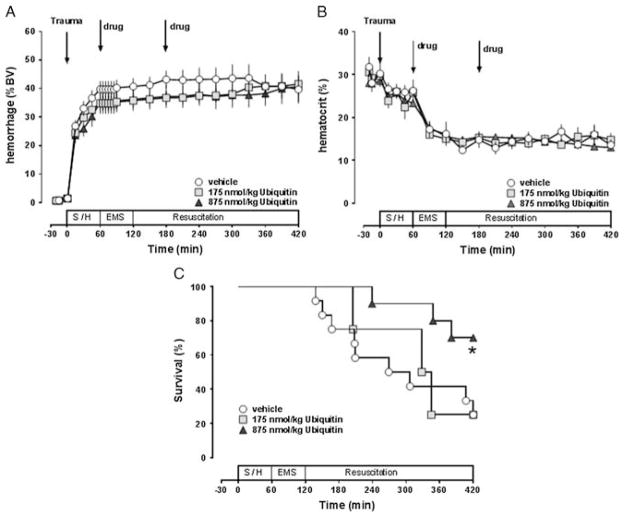

Next, we tested whether the efficacy of ubiquitin to prolong survival in this model could be optimized by repetitive dosing. Thus, we treated animals with vehicle and with 175-nmol/kg or 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin at t = 60 minutes and t = 180 minutes. There were no statistically significant differences in any of the measured parameters at baseline among the groups. As shown in Figure 4A and B, hemorrhage volumes and hematocrit values were comparable in all experimental groups. All animals could be resuscitated to the MAP target within the EMS period. Resuscitation fluid requirements to reach the resuscitation end point during the EMS period were 180 ± 20 mL/kg with vehicle treatment, 123 ± 21 mL/kg after treatment with 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle), and 110 ± 10 mL/kg after treatment with 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin (p < 0.05). As observed in Series 2, mortality occurred because of rapid cardiovascular collapse during subsequent continuous fluid resuscitation (Fig. 4C). Median survival time with vehicle treatment was 288 minutes, and 3 of the 12 animals in this group survived the study end point. When compared with the survival of vehicle-treated animals in Series 2, median survival times of vehicle-treated animals in this series were not significantly different. While double dosing of 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin did not significantly prolong median survival time (336 minutes, p > 0.05 vs. vehicle), double dosing of 875 nmol/kg prolonged the median survival time to longer than 420 minutes, with 7 of the 10 animals surviving the observation period of 420 minutes (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle; hazard ratio [95% confidence interval]: vehicle/875-nmol/kg ubiquitin, 3.6 [1.15 – 11.4]). When survival curves from Series 2 and 3 were combined, median survival time was 226.5 minutes with vehicle treatment and longer than 420 minutes after single-dose treatments with 875-nmol/kg and 1.75-μg/kg ubiquitin and double-dose treatment with 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin (p < 0.05 vs. vehicle for all).

Figure 4.

Ubiquitin treatment after lethal polytrauma and hemorrhage—double dosing. The arrows indicate the time points of polytrauma and drug administration. Shock, shock period; EMS, simulated prehospital emergency medical service period; Resuscitation, simulated in-hospital ICU resuscitation period. Open circles, vehicle (n = 12); light gray squares, 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 4); dark gray triangles, 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 10). Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle. A, Hemorrhage volume in percentage of blood volume (BV). B, Hematocrit values (%). (C), Kaplan-Meier survival plot.

Series 4: Continuous Hemorrhage, No Fluid Resuscitation—Single-Dose Treatment

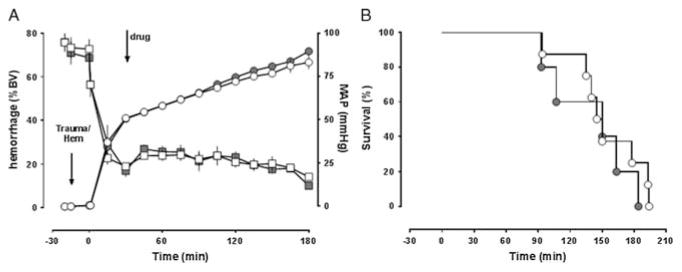

To further evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of ubiquitin, we then tested whether ubiquitin treatment (875 nmol/kg) would provide a survival benefit in a model designed to mimic severe hemorrhagic shock with ongoing bleeding and without additional fluid resuscitation. Thus, animals were hemorrhaged by a fixed blood volume of 40% within 15 minutes, followed by 2% to 3% blood volume hemorrhage every 15 minutes until cardiovascular collapse (Fig. 5A). In this model, survival times were similar with or without polytrauma preceding the hemorrhage period (median survival time, 140 minutes with polytrauma, 178 minutes without polytrauma; p > 0.05). When animals were treated with a single 250-mL IV bolus of vehicle or ubiquitin at t = 15 minutes, however, MAPs (Fig. 5A) and survival times were indistinguishable (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Ubiquitin treatment during continuous hemorrhage without fluid resuscitation. The arrows indicate the time points of polytrauma/start of hemorrhage and drug administration. Open symbols, vehicle (n = 8); gray symbols, 875-nmol/kg ubiquitin (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM. A, Left y-axis, hemorrhage volume in percentage of blood volume (BV), circles. Right y-axis, MAP (mm Hg), squares. B, Kaplan-Meier survival plot.

DISCUSSION

There are several new findings from the present study. First, treatment with the selective CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 after blunt polytrauma increases resuscitation fluid requirements. Second, the beneficial effects of ubiquitin on fluid requirements and survival after polytrauma/hemorrhage show a nonlinear dose-response relationship. Third, ubiquitin treatment provides a survival benefit during resuscitation from polytrauma and severe hemorrhage.

Multiple previous in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that the noncognate CXCR4 agonist ubiquitin has pleiotropic immune modulatory effects in various model systems and also modulates cardiovascular responses to adrenergic receptor stimulation.7,8,22–34 Moreover, we recently provided pharmacologic evidence suggesting that beneficial effects of ubiquitin on fluid requirements and hemodynamic stability in trauma/hemorrhage models are mediated via CXCR4.7,11 Thus, in the present study, we undertook a translational approach and used fluid requirements to maintain hemodynamics and survival as simple but physiologically relevant readouts to further characterize CXCR4 as a pharmacologic target after severe trauma and to provide a systematic evaluation of ubiquitin’s properties as a protein therapeutic.

The resuscitation fluid requirements and survival rates that we observed in the present study in vehicle-treated animals are in agreement with our previous findings in these models.11,18 Furthermore, endogenous ubiquitin levels and the plasma half-life of exogenous ubiquitin that we determined after administration of various doses in the present study are consistent with previously reported plasma levels and plasma half-lives after IV administration of 175-nmol/kg ubiquitin in uninjured animals and in injured animals during fluid resuscitation.15–17

The observed effects of blockade of CXCR4 with AMD3100 and of CXCR4 activation with ubiquitin after blunt polytrauma in the present study are in line with the previously described effects of CXCR4 blockade before polytrauma and with the known pharmacologic properties of ubiquitin.11,17 Thus, these data further support the concept that CXCR4 could be a therapeutic target in trauma patients.

Information on the dose-response relationship of exogenous ubiquitin in vivo, however, is sparse and limited to ubiquitin-induced effects on inflammation markers in a mouse model of cecal ligation and puncture.35 In this model, IV ubiquitin treatment (117–1,170 nmol/kg) at 6 hours after cecal ligation and puncture dose-dependently reduced tumor necrosis factor α concentrations in lung homogenates.35 In the present study, dose-dependent effects of ubiquitin on relevant outcome parameters could be observed in three different experimental protocols. When administered at the beginning of fluid resuscitation after polytrauma and hemorrhage, a single IV dose of 875 nmol/kg showed highest efficacy. While higher and repetitive doses did not increase therapeutic efficacy, no acute toxicity was observed. These findings suggest that the mechanism underlying therapeutic effects of ubiquitin is saturable, which is consistent with CXCR4-mediated modulation of vascular function during the cardiovascular stress response.7,8 Furthermore, the absence of acute toxicity after high or repetitive doses of ubiquitin in the present study is in agreement with multiple previous studies in mice, gerbils, rats, and pigs, including continuous intraperitoneal administration for up to 2 weeks in mice, which collectively suggest ubiquitin as a biologically safe protein therapeutic.7,14,15,17,35–39 It should be noted, however, that a systematic toxicity testing of ubiquitin has hitherto not been performed and long-term consequences of ubiquitin treatment are unknown.

We and others have previously reported that a single dose of ubiquitin modulates inflammation, reduces tissue injury, reduces fluid resuscitation requirements, and stabilizes hemodynamics in multiple animal models and species, including models of endotoxic shock,14 hemorrhagic shock,7 lung and brain ischemia-reperfusion injury,36,38 mild and severe brain injury,16,39 extremity trauma plus hemorrhage,15 and blunt polytrauma.17 The findings from the present study now extend the preclinical efficacy profile of ubiquitin and demonstrate that ubiquitin treatment provides a survival benefit in a large animal model of lethal polytrauma and hemorrhage. In addition, these data show that previous observations from short-term hemorrhage models in rats largely translate to more complex large animals models.7

We observed previously, however, that ubiquitin treatment significantly prolonged survival time during continuous hemorrhage without fluid resuscitation in rats,7 whereas ubiquitin treatment in the present study did not influence median survival time in a similar model in pigs. This observation remains ambiguous as we have tested only a single-dosing regimen. Thus, we cannot exclude that other dosing regimens, such as higher or repetitive dosing, would be required in pigs. In contrast, these data may provide initial information on the efficacy limits of this therapeutic approach in a more complex large animal model.

Recently, we provided evidence that CXCR4 modulates vascular α1-adrenergic receptor function.7,8 As CXCR4 activation with ubiquitin enhanced vasoconstriction of isolated arteries and veins in response to α1-adrenergic receptor activation and sensitized phenylephrine-induced blood pressure responses in vivo,7,8 the beneficial effects of ubiquitin treatment in the present study could, at least partially, be attributed to the modulation of preload and afterload during the cardiovascular stress response to traumatic/hemorrhagic shock. Furthermore, the finding that ubiquitin treatment reduced resuscitation fluid requirements while hematocrit values were comparable in vehicle-and ubiquitin-treated animals in the present study is consistent with previous observations and infers that CXCR4 activation also reduces third spacing of fluids during the inflammatory response to traumatic/hemorrhagic shock.7,11,14–17,38

Limitations of the present study are that our models do not mimic several aspects of clinical trauma care, such as blood transfusion, antibiotic treatment, or early fracture stabilization and that we used a rigid resuscitation regimen with a MAP target of 70 mm Hg, which could result in fluid overload. Nevertheless, these models reliably resemble the human cardiovascular stress response to traumatic/hemorrhagic shock and permit treatment according to human advanced trauma life support guidelines.11,15,17,18

In conclusion, the present study further supports the notion that CXCR4 is a promising therapeutic target after trauma and hemorrhage. Our findings indicate that therapeutic effects of exogenous ubiquitin occur dose dependently, provide initial information on an optimized dosing regimen, and suggest that treatment with exogenous ubiquitin reduces the incidence of cardiovascular collapse during resuscitation from polytrauma and severe hemorrhage.

Footnotes

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this research are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense and should not be construed as an official Department of Defense/Army position, policy or decision unless so designated by other documentation. No official endorsement should be made.

AUTHORSHIP

H.H.B., Y.M.W., and H.M.L. performed the experiments. H.H.B., Y.M.W., H.M.L., and M.M. analyzed the data. M.M. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. R.L.G. contributed to the study design and interpretation of data.

DISCLOSURE

This research was made possible by a grant that was awarded and administered by the US Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (USAMRMC) and the Telemedicine & Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC), at Fort Detrick, Maryland, under Contract Number W81XWH1020122. This research was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Awards Number R01GM107495 and T32GM008750) and the Dr. Ralph and Marian Falk Medical Research Trust.

The therapeutic use of ubiquitin has been patented (US patent #7,262,162), and M.M. is an inventor. M.M. has not received any income related to this patent.

References

- 1.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(14):1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma. 2006;60(6 Suppl):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199961.02677.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez H, Mesquida J, Hermus L, Polanco P, Kim HK, Zenker S, Torres A, Namas R, Vodovotz Y, Clermont G, et al. Physiologic responses to severe hemorrhagic shock and the genesis of cardiovascular collapse: can irreversibility be anticipated? J Surg Res. 2012;178(1):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohn SM, Blackbourne LH, Landry DW, Proctor KG, Walley KR, Wenzel V. San Antonio Vasopressin in Shock Symposium report. Resuscitation. 2010;81(11):1473–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anand T, Skinner R. Arginine vasopressin: the future of pressure-support resuscitation in hemorrhagic shock. J Surg Res. 2012;178(1):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cossu AP, Mura P, De Giudici LM, Puddu D, Pasin L, Evangelista M, Xanthos T, Musu M, Finco G. Vasopressin in hemorrhagic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized animal trials. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:421291. doi: 10.1155/2014/421291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach HH, 4th, Wong YM, Tripathi A, Nevins AM, Gamelli RL, Volkman BF, Byron KL, Majetschak M. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 and atypical chemokine receptor 3 regulate vascular α1-adrenergic receptor function. Mol Med. 2014;20:435–447. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tripathi A, Vana PG, Chavan TS, Brueggemann LI, Byron KL, Tarasova NI, Volkman BF, Gaponenko V, Majetschak M. Heteromerization of chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 with α1A/B-adrenergic receptors controls α1-adrenergic receptor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(13):E1659–E1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417564112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu PY, Zatta A, Kiriazis H, Chin-Dusting J, Du XJ, Marshall T, Kaye DM. CXCR4 antagonism attenuates the cardiorenal consequences of mineral-ocorticoid excess. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(5):651–658. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.960831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu L, Hales CA. Effect of chemokine receptor CXCR4 on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in rats. Respir Res. 2011;12:21. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bach HH, 4th, Saini V, Baker TA, Tripathi A, Gamelli RL, Majetschak M. Initial assessment of the role of CXC chemokine receptor 4 after polytrauma. Mol Med. 2012;18:1056–1066. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gambaryan N, Perros F, Montani D, Cohen-Kaminsky S, Mazmanian M, Renaud JF, Simonneau G, Lombet A, Humbert M. Targeting of c-kit + haematopoietic progenitor cells prevents hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1392–1399. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00045710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan H, Wong D, Ashton SH, Borg KT, Halushka PV, Cook JA. Beneficial effect of a CXCR4 agonist in murine models of systemic inflammation. Inflammation. 2011;35(1):130. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9297-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majetschak M, Cohn SM, Nelson JA, Burton EH, Obertacke U, Proctor KG. Effects of exogenous ubiquitin in lethal endotoxemia. Surgery. 2004;135(5):536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majetschak M, Cohn SM, Obertacke U, Proctor KG. Therapeutic potential of exogenous ubiquitin during resuscitation from severe trauma. J Trauma. 2004;56(5):991–999. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000127770.29009.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earle SA, Proctor KG, Patel MB, Majetschak M. Ubiquitin reduces fluid shifts after traumatic brain injury. Surgery. 2005;138(3):431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker TA, Romero J, Bach HH, 4th, Strom JA, Gamelli RL, Majetschak M. Effects of exogenous ubiquitin in a polytrauma model with blunt chest trauma. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2376–2384. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182514ed9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker TA, Romero J, Bach HH, 4th, Strom JA, Gamelli RL, Majetschak M. Systemic release of cytokines and heat shock proteins in porcine models of polytrauma and hemorrhage*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):876–885. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232e314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dudkiewicz M, Harpaul TA, Proctor KG. Hemoglobin-based oxygen carrying compound-201 as salvage therapy for severe neuro- and polytrauma (Injury Severity Score = 27–41) Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2838–2848. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186f6b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenspan L, McLellan BA, Greig H. Abbreviated Injury Scale and Injury Severity Score: a scoring chart. J Trauma. 1985;25(1):60–64. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majetschak M, Zedler S, Hostmann A, Sorell LT, Patel MB, Novar LT, Kraft R, Habib F, de Moya MA, Ertel W, et al. Systemic ubiquitin release after blunt trauma and burns: association with injury severity, posttraumatic complications, and survival. J Trauma. 2008;64(3):586–596. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181641bc5. discussion 96–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saini V, Marchese A, Majetschak M. CXC chemokine receptor 4 is a cell surface receptor for extracellular ubiquitin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(20):15566–15576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saini V, Staren DM, Ziarek JJ, Nashaat ZN, Campbell EM, Volkman BF, Marchese A, Majetschak M. The CXC chemokine receptor 4 ligands ubiquitin and stromal cell-derived factor-1α function through distinct receptor interactions. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(38):33466–33477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan L, Cai Q, Xu Y. The ubiquitin-CXCR4 axis plays an important role in acute lung infection-enhanced lung tumor metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(17):4706–4716. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muppidi A, Doi K, Edwardraja S, Pulavarti SV, Szyperski T, Wang HG, Lin Q. Targeted delivery of ubiquitin-conjugated BH3 peptide-based Mcl-1 inhibitors into cancer cells. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25(2):424–432. doi: 10.1021/bc4005574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steagall RJ, Daniels CR, Dalal S, Joyner WL, Singh M, Singh K. Extracellular ubiquitin increases expression of angiogenic molecules and stimulates angiogenesis in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Microcirculation. 2014;21(4):324–332. doi: 10.1111/micc.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan C, Lu X, Chen W, Chen S. Serum ubiquitin via CXC chemokine receptor 4 triggered cyclooxygenase-1 ubiquitination possibly involved in the pathogenesis of aspirin resistance. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2014 doi: 10.3233/CH-141900. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Cao Y, Li C, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Xia R. Extracellular ubiquitin enhances the suppressive effects of regulatory T cells on effector T cell responses. Clin Lab. 2014;60(12):1983–1991. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2014.140314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majetschak M, Krehmeier U, Bardenheuer M, Denz C, Quintel M, Voggenreiter G, Obertacke U. Extracellular ubiquitin inhibits the TNF-alpha response to endotoxin in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and regulates endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in critical illness. Blood. 2003;101(5):1882–1890. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniels CR, Foster CR, Yakoob S, Dalal S, Joyner WL, Singh M, Singh K. Exogenous ubiquitin modulates chronic β-adrenergic receptor-stimulated myocardial remodeling: role in Akt activity and matrix metalloproteinase expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(12):H1459–H1468. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00401.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh M, Roginskaya M, Dalal S, Menon B, Kaverina E, Boluyt MO, Singh K. Extracellular ubiquitin inhibits beta-AR–stimulated apoptosis in cardiac myocytes: role of GSK-3beta and mitochondrial pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86(1):20–28. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majetschak M. Extracellular ubiquitin: immune modulator and endogenous opponent of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(2):205–219. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0510316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu X, Yu B, You P, Wu Y, Fang Y, Yang L, Xia R. Ubiquitin released in the plasma of whole blood during storage promotes mRNA expression of Th2 cytokines and Th2-inducing transcription factors. Transfus Apher Sci. 2012;47(3):305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daino H, Shibayama H, Machii T, Kitani T. Extracellular ubiquitin regulates the growth of human hematopoietic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;223(2):226–228. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He Z-Y, Xing J. Ubiquitin reduces expression of intercellular adhesion molecules and tumor necrosis factor-α in lung tissue of experimental acute lung injury. World J Vaccines. 2012;2:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn HC, Yoo KY, Hwang IK, Cho JH, Lee CH, Choi JH, Li H, Cho BR, Kim YM, Won MH. Ischemia-related changes in naive and mutant forms of ubiquitin and neuroprotective effects of ubiquitin in the hippocampus following experimental transient ischemic damage. Exp Neurol. 2009;220(1):120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Earle SA, El-Haddad A, Patel MB, Ruiz P, Pham SM, Majetschak M. Prolongation of skin graft survival by exogenous ubiquitin. Transplantation. 2006;82(11):1544–1546. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000236057.56721.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Covarrubias L, Manning EW, 3rd, Sorell LT, Pham SM, Majetschak M. Ubiquitin enhances the Th2 cytokine response and attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the lung. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):979–982. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E318164E417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griebenow M, Casalis P, Woiciechowsky C, Majetschak M, Thomale UW. Ubiquitin reduces contusion volume after controlled cortical impact injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(9):1529–1535. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]