Abstract

Aims

Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) contributes to a multitude of physiological and pathophysiological functions in pulmonary vasculatures. SOCE attributable to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R)-gated Ca2+ store has been studied extensively, but the role of ryanodine receptor (RyR)-gated store in SOCE remains unclear. The present study aims to delineate the relationship between RyR-gated Ca2+ stores and SOCE, and characterize the properties of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs).

Methods and results

PASMCs were isolated from intralobar pulmonary arteries of male Wister rats. Application of the RyR1/2 agonist 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC) activated robust Ca2+ entry in PASMCs. It was blocked by Gd3+ and the RyR2 modulator K201 but was unaffected by the RyR1/3 antagonist dantrolene and the InsP3R inhibitor xestospongin C, suggesting RyR2 is mainly involved in the process. siRNA knockdown of STIM1, TRPC1, and Orai1, or interruption of STIM1 translocation with ML-9 significantly attenuated the 4-CmC-induced SOCE, similar to SOCE induced by thapsigargin. However, depletion of RyR-gated store with caffeine failed to activate Ca2+ entry. Inclusion of ryanodine, which itself did not cause Ca2+ entry, uncovered caffeine-induced SOCE in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting binding of ryanodine to RyR is permissive for the process. This Ca2+ entry had the same molecular and pharmacological properties of 4-CmC-induced SOCE, and it persisted once activated even after caffeine washout. Measurement of Ca2+ in sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) showed that 4-CmC and caffeine application with or without ryanodine reduced SR Ca2+ to similar extent, suggesting store-depletion was not the cause of the discrepancy. Moreover, caffeine/ryanodine and 4-CmC failed to initiate SOCE in cells transfected with the ryanodine-binding deficient mutant RyR2-I4827T.

Conclusions

RyR2-gated Ca2+ store contributes to SOCE in PASMCs; however, store-depletion alone is insufficient but requires a specific RyR conformation modifiable by ryanodine binding to activate Ca2+ entry.

Keywords: Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), Ryanodine receptor (RyR), Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), Canonical transient receptor potential 1 (TRPC1), Pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells

1. Introduction

Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) or capacitative Ca2+ entry1 has been implicated in diverse vascular functions, such as regulation of arterial tone, agonist-induced vasoconstriction, vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation, and vascular remodelling.2 It is established that vasoactive agonists of Gq-protein-coupled receptors and receptor tyrosine kinases activate phospholipase C, generating inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) to activate InsP3-receptors (InsP3Rs) for Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). The subsequent decrease in SR Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]SR) is detected by the Ca2+ sensor stromal interaction molecule (STIM), which oligomerizes and translocates to the SR-plasma membrane (PM) junctions where it couples and activates store-operated Ca2+ channels, including Orai and canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channels, to mediate Ca2+ influx. Despite SR is a continuous interconnected tubular network, SR Ca2+ stores in VSMCs are functionally segregated, attributable to the differences in spatial distributions and properties of InsP3Rs, ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases (SERCA).3 Hence, SOCE is likely to be regulated differentially by functionally distinct SR Ca2+ stores.

In addition to InsP3R, RyR-gated Ca2+ release plays many pivotal roles in Ca2+ signalling in VSMCs, including excitation–contraction/pharmaco-mechanical coupling, transcription regulation, and activation of enzymatic processes.4 Depending on the physiological stimuli, Ca2+ release from RyR can cause global elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) to activate actin–myosin interaction for vasoconstriction, and generate local Ca2+ signals in SR–PM junctions to stimulate Ca2+-activated channels to modulate membrane potential and Ca2+ influx via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. However, the role of RyR-gated stores in SOCE in VSMCs has not been clearly defined. Previous studies have reported caffeine and ryanodine-sensitive SOCE in several cell types5–8; but the properties of RyR-mediated SOCE are quite different from the conventional SOCE. For example, robust RyR-sensitive SOCE is present only in embryonic and neonatal cardiac myocytes, but it is absent in adult myocytes,9 despite InsP3R-gated SOCE and its machineries STIM1, Orai1, and TRPC channels are all fully operational.10,11 In skeletal muscle, RyR-sensitive SOCE is dependent on RyR1 and the integrity of the junctional complex, but it is distinguishable from the thapsigargin-induced SOCE.5,12 A SOCE independent RyR1-mediated ‘excitation-coupled Ca2+ influx’ has also been reported in skeletal muscle.13 Furthermore, physical association between RyR1 and TRPC channels have been demonstrated in heterologous systems, suggesting conformational coupling can be involved in RyR1-mediated Ca2+ entry.14,15

In pulmonary arteries (PAs), SOCE is a major Ca2+ pathway responsible for vasomotor tone,16 agonist-induced contraction,17 hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV),18 and pulmonary hypertension.16,19 RyR-dependent Ca2+ release is also crucial for agonist-induced contraction, HPV, and spontaneous contraction of chronic hypoxic PAs.20–23 However, the mechanistic connection between RyR and SOCE in PASMCs has not been established.24,25 We have previously demonstrated that the three RyR subtypes are differentially expressed in peripheral and perinuclear SR of PASMCs, and are associated with local Ca2+ events of distinctive spatial and temporal characteristics.26–28 RyR-dependent Ca2+ events can serve as the signal multiplier for amplifying the InsP3- and NAADP-induced Ca2+ response,20,29 and as the trigger for activation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channel.30 However, whether RyR-gated Ca2+ store can independently activate SOCE in PASMCs is unclear.24,25 In the present study, we characterized the physiological and molecular properties of RyR-dependent SOCE in PASMCs. We found that depletion of RyR-sensitive stores alone is insufficient but a specific change of RyR conformation is required for the activation of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry. These observations provide novel information on RyR-gated Ca2+ entry and suggest a unique mechanism of SOCE activation in pulmonary vasculature.

2. Methods

2.1. PASMC isolation

All animal procedures conformed to the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. Lungs were harvested from male Wistar rats (150–250 g) anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (130 mg/kg) intraperitoneally. Intralobar PAs were isolated and de-endothelialized. PASMCs were enzymatically dissociated and cultured transiently (16–24 h) before experiment as described previously.20

2.2. Cytosolic and SR Ca2+ measurements

Cytosolic and SR [Ca2+] were monitored using fluo-3 AM and fluo-5N AM, respectively.26,29 Fluorescent dyes were excited at 488 nm and emission light at >515 nm was detected using a Nikon Diaphot microscope equipped with epifluorescence attachments and a microfluorometer. Ca2+ transients were recorded and calibrated as previously described.29

2.3. Transfection of PASMCs with siRNA

Freshly isolated PASMCs were cultured for 16–18 h and then transiently transfected with siRNA specific for STIM1 (5′-GGGAAGACCUCAAUUACCAUU-3′), TRPC1 (5′-GAAUUUAAGUCGUCUGAAAUU-3′), ORAI1 (5′-AGUUCUUACCGCUCAAGAGGCAGGC-3′), or a random non-silencing sequence with DharmaFECT transfection reagent (Dharmacon) according to manufacturer's instruction. PASMCs were further cultured with transfection mixture in serum-free OptiMEM medium for 48 h before experiment.

2.4. DNA transfection and preparation of HEK293 cell lysates

RyR2 wild-type and RyR-I4827T mutant plasmids were supplied by Dr S.R. Wayne Chen (University of Calgary). HEK293 cells were transfected with RyR2 plasmids using Ca2+ phosphate precipitation, and cell lysates were prepared from transfected cells as described previously.31

2.5. Immunoblotting analysis

Solubilized protein samples were resolved on a 5–8% (w/v) gradient SDS–PAGE gel and electrotransferred onto a PVDF membrane at 45 V for 20–22 h at 4°C in Towbin buffer with 10% methanol and 0.01% (w/v) SDS. Standard western blot protocol was then followed. Specific primary antibodies against RyR2 (Thermo Scientific, 1:1000), STIM1 (BD Biosciences, 1:1000), TRPC1 (Alomone, 1:1000), Orai1 (Thermo Scientific, 1:1000), or actin (Santa Cruz, 1:5000) were used. The band intensities were normalized with actin.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. N denotes the number of experiments, each represents the response recorded from a group of cells under the field of the fluorescence microscope. Each set of experiments were performed in cells isolated from three or more animals. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was assessed by unpaired Student's t-test, one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak method for multiple comparison, non-parametric Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test, or Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks with Dunn's test for multiple comparisons wherever applicable.

3. Results

3.1. The RyR agonist, 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC), induced Ca2+ entry in PASMCs

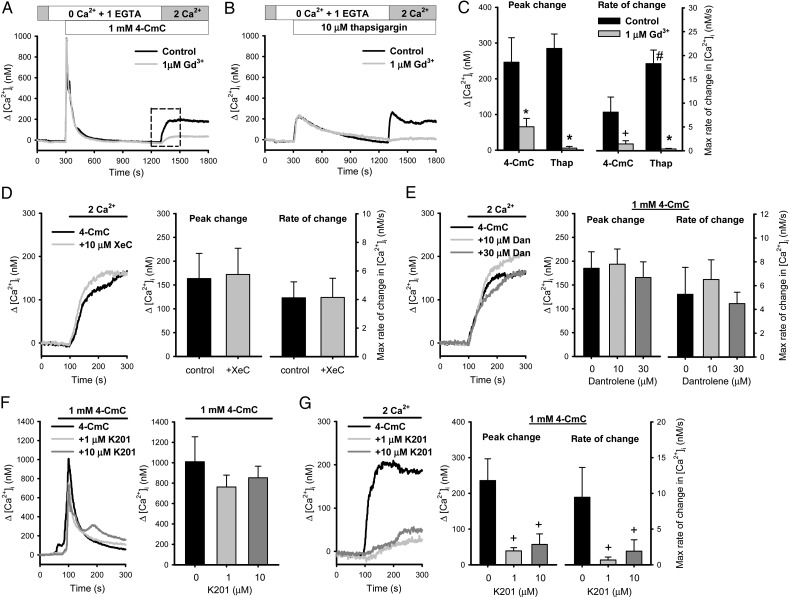

To study RyR-gated Ca2+ entry, the RyR agonist 4-CmC was applied to PASMCs under Ca2+ free condition to activate RyR (Figure 1A). Ca2+ entry was elicited by reintroduction of extracellular Ca2+ (2 mmol/L) after 1000 s in the presence of 1 μmol/L nifedipine, the peak and maximium rate of change of Ca2+ transient at 1300–1500 s was quantified for comparison. 4-CmC (1 mmol/L) activated a fast robust Ca2+ release that last for 100–200 s under Ca2+-free condition and a sustained Ca2+ influx (Δ[Ca2+]i: 246 ± 68 nmol/L, n = 9) (Figure 1C) upon re-introduction of extracellular Ca2+. The 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ influx was inhibited by a low concentration of Gd3+ (1 μmol/L; Δ[Ca2+]i: 65 ± 23 nmol/L, n = 10; P < 0.05). SOCE was elicited by thapsigargin using the same protocol for comparison (Figure 1B). Depletion of SR Ca2+ stores of PASMCs with 10 μmol/L thapsigargin activated similar peak Ca2+ entry but with significantly faster rate of increase compared with 4-CmC, and Ca2+ entry was abolished by Gd3+ (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

The RyR agonist 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC) induced Ca2+ entry in PASMCs. Averaged tracings showing (A) 4-CmC (1 mmol/L) and (B) thapsigargin (10 μmol/L)-induced Ca2+ entry in the absence or presence of Gd3+ (1 μmol/L). (C) The Ca2+ entry component (1300–1500 s) quantified as averaged peak and maximum rate of increase of Ca2+ transients [n = 5–10 experiments from six animals, ‘asterisk’ indicates P < 0.05 vs. control (unpaired t-test); ‘plus’ indicates P < 0.05 vs. control, and ‘hash’ indicates P < 0.05 vs. 4-CmC (Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test)]. (D) 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry in PASMCs with or without pre-incubation with xestospongin C (XeC)(10 μmol/L) (n = 16 experiments from eight animals). (E) Effect of dantrolene (Dan; 10, 30 μmol/L) on 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ influx (n = 8–11 experiments from six animals). (F and G) The effect of K201 (1, 10 μmol/L) on the Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry induced by 4-CmC (n = 8–12 experiments from five animals, ‘plus’ indicates P < 0.05 using Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks).

There is substantial evidence showing cross-talks between InsP3R and RyR via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release,20 and depletion of InsP3R-gated store activates SOCE.1 The possible involvement of InsP3R in 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry was examined. Pre-incubation of PASMCs with the InsP3R inhibitor xestospongin C (10 μmol/L) for 1 h, which effectively inhibits InP3R-mediated Ca2+ mobilization in PASMCs,29 had no significant effect on the 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ influx (Figure 1D), suggesting that it is independent of the InsP3R-gated SOCE pathway.

3.2. RyR2 mediates RyR-gated Ca2+ entry in PASMCs

RyR1, RyR2, and RyR3 are expressed in PASMCs.26 Specific RyR agonists and inhibitors were used to identify the RyR subtype involved. Maurocalcine (400 nmol/L), which specifically activates RyR1,32 failed to induce Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry in PASMCs (data not shown, n = 9). Dantrolene, which inhibits Ca2+ release through RyR1 and RyR3 but not RyR2,33 had no significant effect on 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry (Figure 1E). In contrast, the anti-arrhythmic drug K201, which increases the affinity of FKBP12.6 (calstabin2) for stabilizing the closed-state of RyR2 at rest,34,35 had no significant effect on 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ release but caused significant inhibition of 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry (Figure 1F and G). The peak Ca2+ responses were 39 ± 9 and 57 ± 30 nmol/L (n = 8–11; P < 0.05) at 1 and 10 μmol/L K201, respectively, compared with the control of 236 ± 61 nmol/L (n = 12). The rates of increase in [Ca2+]i were also significantly slower in the presence of K201. These data indicate that RyR2 is the major RyR subtype responsible for the RyR-gated Ca2+ entry in PASMCs.

3.3. RyR-gated Ca2+entry is mediated through STIM1, TRPC1, and Orai1

The molecular partners in the RyR-gated Ca2+ entry were examined by using siRNA. Transfection of PASMCs with siRNA against STIM1 resulted in 58% reduction in STIM1 protein compared with a non-silencing scrambled siRNA (n = 5, P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). The thapsigargin-induced SOCE was significantly attenuated in STIM1 siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 2B). 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry was also reduced in STIM1 siRNA-transfected PASMCs (n = 8; P < 0.05) (Figure 2C). Moreover, interruption of the STIM1 translocation using ML-9 (100 μmol/L)36 significantly inhibited thapsigargin (Figure 2D) and 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry (Figure 2E). Previous studies showed that TRPC1 and Orai1 are store-operated cation channels in PASMCs.16,37 Their contributions to RyR-gated Ca2+ entry were examined. TRPC1 and Orai1 protein expression were reduced by 62% and 53%, respectively, in the siRNA-transfected PASMCs (Figure 3A and D). Knockdown of TRPC1 or Orai1 caused significant reduction of thapsigargin-induced SOCE (Figure 3B and E). Moreover, 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry was significantly attenuated in TRPC1 siRNA-transfected cells (control: 94 ± 20 nmol/L, n = 10; TRPC1 siRNA: 40 ± 10 nmol/L, n = 8; P < 0.05) (Figure 3C) and Orai1 siRNA-transfected cells (control: 131 ± 20 nmol/L, n = 7; Orai1 siRNA: 61 ± 22 nmol/L, n = 7; P < 0.05) (Figure 3F). siRNA of STIM1, TRPC1, and Orai1 and the blockers had no or little effect on the resting [Ca2+]i (Supplementary material online, Figure S1). These results clearly showed that RyR-gated Ca2+ influx activated by 4-CmC share similar properties with thapsigargin-induced SOCE and is mediated through STIM1, TRPC1, and Orai1 in PASMCs.

Figure 2.

RyR-gated Ca2+ entry is mediated by STIM1. (A) Western blot and normalized amount of STIM1 protein in PASMCs transfected with STIM1 siRNA or control scrambled siRNA (n = 5 experiments from five animals). (B) Ca2+ influx induced by thapsigargin or (C) 4-CmC in PASMCs transfected with siRNA against STIM1 or control siRNA (n = 7–8 experiments from five animals). (D) Effect of ML-9 (100 μmol/L) on thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ entry (n = 6–7 experiments from three animals) or (E) 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ entry (n = 7–8 experiments from three animals). ‘Asterisk’ indicates P < 0.05 using unpaired t-test and ‘plus’ indicates P < 0.05 using Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test.

Figure 3.

RyR-gated Ca2+ entry is mediated by TRPC1 and Orai1. (A) Western blot and normalized TRPC1 protein level in PASMCs transfected with TRPC1 siRNA or control siRNA (n = 7 experiments from seven animals). (B) Ca2+ influx induced by thapsigargin or (C) by 4-CmC in PASMCs transfected with siRNA against TRPC1 or control siRNA (n = 8–10 experiments from three animals). (D) Western blot and normalized amount of Orai1 protein in Orai1 siRNA or scrambled control-transfected PASMCs (n = 7 experiments from seven animals). (E) Ca2+ influx induced by thapsigargin or (F) by 4-CmC in PASMCs transfected with Orai1-specific or control scrambled siRNA (n = 7–13 experiments from five animals). ‘Asterisk’ indicates P < 0.05 using unpaired t-test and ‘plus’ indicates P < 0.05 using Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test.

It is noted that the thapsigargin-induced SOCE was enhanced and the 4-CmC-induced SOCE was reduced in the control siRNA-transfected PASMCs compared with the control PASMCs (Figure 1). Examining the pooled data found that the resting [Ca2+]i was significantly elevated, the thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ release was significantly enhanced, while the 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ release was reduced in the control siRNA-transfected cells (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2). These results suggest that the siRNA transfection procedure have different effects on the thapsigargin- and 4-CmC-sensitive Ca2+ stores. There was a report suggested that 4-CmC at 1 mM have a minor inhibitory effect (10–15%) on SERCA activity.38 The differential changes in the thapsigargin and 4-CmC-induced SOCE in the control siRNA-transfected cells indicates that 4-CmC activates SOCE through a mechanism independent of SERCA inhibition.

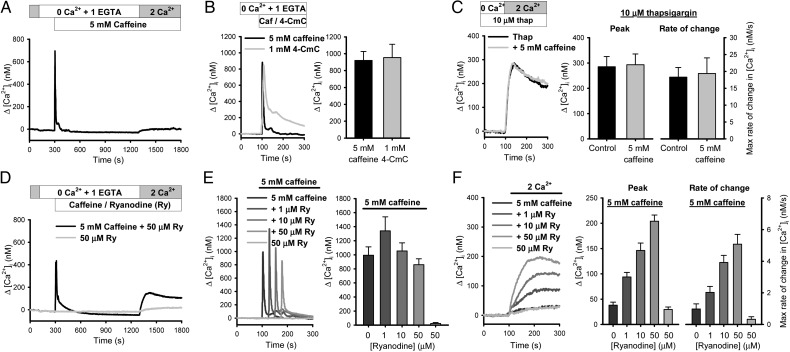

3.4. Caffeine induces Ca2+ entry only in the presence of ryanodine

In contrast to 4-CmC, application of 5 mmol/L caffeine activated large Ca2+ release, but failed to induce SOCE (Figure 4A). The inability of caffeine to induce SOCE was not due to insufficient activation of RyR-gated Ca2+ store because the amplitudes of Ca2+ release induced by caffeine and 4-CmC were comparable (Figure 4B). It was also not due to an inhibitory effect of caffeine on SOCE, because caffeine did not alter the thapsigargin-induced SOCE in PASMCs (Figure 4C). These results suggest that activation of RyR-gated Ca2+ store alone is insufficient to cause RyR-gated Ca2+ entry.

Figure 4.

Caffeine induces RyR-gated Ca2+ entry only in the presence of ryanodine. (A) Caffeine (5 mmol/L) failed to induce Ca2+ entry in PASMCs. (B) Averaged Ca2+ traces and peak [Ca2+]i values of caffeine and 4-CmC-induced Ca2+ release (n = 10–23 experiments from 20 animals). (C) Caffeine had no inhibitory effect on thapsigargin-induced SOCE (n = 9 experiments from three animals). (D) Effect of ryanodine (50 μmol/L) and ryanodine+caffeine (5 mmol/L) on Ca2+ influx in PASMCs. (E) Mean traces and averaged peak values showing the change in [Ca2+]i during initial Ca2+ release activated by 5 mmol/L caffeine (Caf) in the absence or presence of different concentrations of ryanodine (Ry) or by 50 μmol/L ryanodine alone. The traces were shifted by 50 s for better display. (F) Mean traces, peak change, and maximum rate of change in [Ca2+]i evoked by 5 mmol/L caffeine (Caf) in the absence or presence of different concentrations of ryanodine (Ry) or by ryanodine alone (n = 8–15 experiments from nine animals).

Caffeine-induced Ca2+ response was further examined in the presence of ryanodine because previous studies had successfully used caffeine and ryanodine simultaneously to activate SOCE in canine renal arterial smooth muscle cells.25 Ryanodine (50 μmol/L) alone did not induce Ca2+ influx, but application of caffeine and ryanodine together caused robust Ca2+ entry (Figure 4D). Addition of ryanodine 300 s after caffeine application also activated significant Ca2+ influx (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3) suggesting ryanodine exerts its effect after RyR activation. Inclusion of ryanodine at various concentrations had no significant effect on caffeine-induced Ca2+ release (Figure 4E), but uncovered caffeine-induced Ca2+ influx in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4F). These data suggest that ryanodine is capable of conferring Ca2+ influx to caffeine-induced RyR activation and the effect is not related to promoting caffeine-induced Ca2+ release for further SR Ca2+ depletion.

The caffeine-induced Ca2+ influx in the presence of 50 μmol/L ryanodine was abolished by Gd3+ (Figure 5A). Pre-incubation of PASMCs with xestospongin C did not alter the caffeine/ryanodine-induced response (Figure 5B). K201, which had no effect on the Ca2+ release, significantly attenuated Ca2+ influx activated by caffeine and ryanodine (n = 8–9, P < 0.05)(Figure 5C). Moreover, transfection of PASMCs with siRNA against STIM1 and interruption of STIM1 translocation with ML-9 significantly attenuated the Ca2+ entry (Figure 5D and E). Caffeine/ryanodine-induced Ca2+ entry was also significantly inhibited in TRPC1 siRNA and Orai1 siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 5F and G). These results demonstrated that the molecular and pharmacological properties of caffeine/ryanodine-induced Ca2+ entry are similar to the RyR-gated Ca2+ entry activated by 4-CmC.

Figure 5.

Caffeine and ryanodine activates Ca2+ entry with characteristics of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry. (A) Effect of 1 μmol/L Gd3+ on Ca2+ influx induced by 5 mmol/L caffeine and 50 μmol/L ryanodine (n = 8 experiments from two animals, *P ≤ 0.001, unpaired t-test). (B) Ca2+ influx induced by caffeine and ryanodine with or without pre-incubation with 10 μmol/L xestospongin C (XeC) (n = 6–7 experiments from three animals). (C) Inhibition of caffeine/ryanodine-induced Ca2+ entry by K201 (1, 10 μmol/L) (n = 8–9, *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (D) Ca2+ influx induced by caffeine/ryanodine in PASMCs transfected with siRNA against STIM1 (n = 8–9 experiments from four animals, *P < 0.05, unpaired t-test). (E) Effect of interruption of STIM1 translocation by ML-9 (100 μmol/L) on caffeine/ryanodine-induced Ca2+ entry (n = 6 experiments from two animals, *P < 0.05, unpaired t-test). (F) Ca2+ influx induced by caffeine/ryanodine in PASMCs transfected with siRNA against TRPC1, (G) Orai1 or control scrambled siRNA (n = 6–9 experiments from three animals, ‘asterisk’ indicates P < 0.05 and ‘a’ indicates P = 0.6 unpaired t-test).

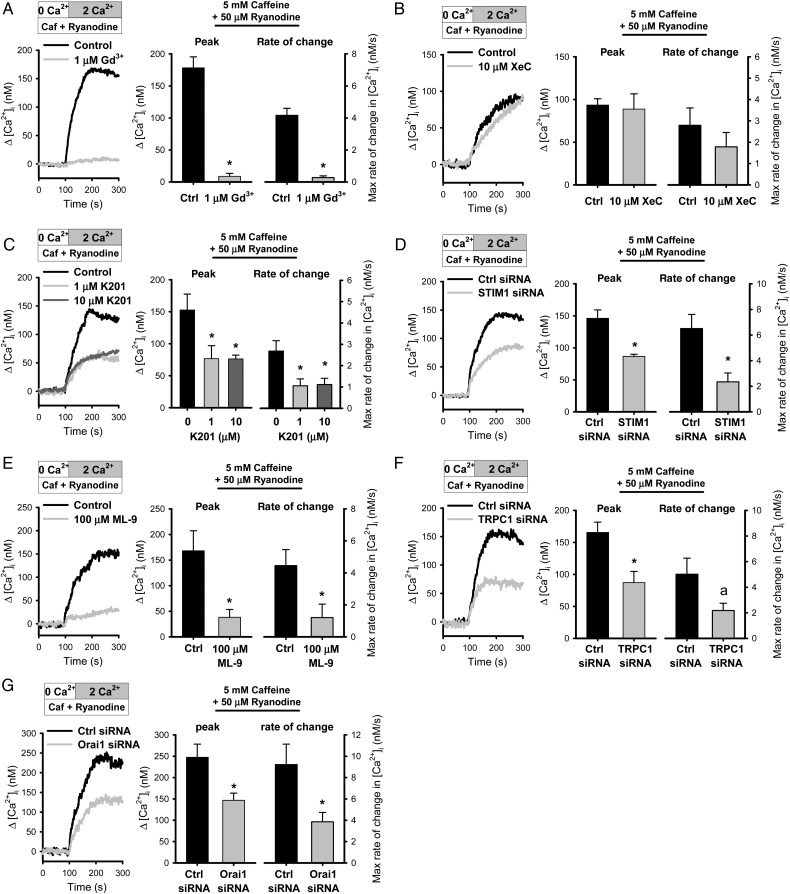

3.5. Caffeine-induced store-depletion was insufficient for activation of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry

To examine agonist-induced SR Ca2+ depletion, the intra-SR Ca2+ content was measured using the low affinity Ca2+ dye Fluo-5N-AM.39 4-CmC caused a rapid sustained reduction in Fluo-5N signal indicating Ca2+ depletion in the RyR-gated SR Ca2+ stores (Figure 6A). Application of caffeine with/without ryanodine under Ca2+-free condition caused a transient increase in Fluo-5N signal presumably due to an increase in local Ca2+ microdomains detected by the residual cytosolic Fluo-5N (Figure 6B). SR store depletion was revealed by the subsequent fall in Fluo-5N signal (Figure 6C). SR Ca2+ content was reduced to the same level as 4-CmC by caffeine in the absence or presence of ryanodine, when quantified at 1000 s for comparison (ΔF/F0 of 4-CmC: 0.48 ± 0.06, n = 5; caffeine: 0.42 ± 0.04, n = 7; caffeine + ryanodine: 0.43 ± 0.05, n = 5; P = 0.67).

Figure 6.

Store release is insufficient for activation of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry. (A) Averaged luminal [Ca2+]SR traces showing store depletion by 4-CmC, or (B) by caffeine in the absence or presence of ryanodine. (C) Mean reduction in [Ca2+]SR signal caused by 4-CmC and caffeine in the presence or absence of ryanodine measured at 900–1000 s after application (n = 5–7 experiments from four animals). (D) Measurement of cytosolic [Ca2+]i after application of a 10 s-pulse of caffeine to PASMCs superfused with Ca2+-containing solution with/without ryanodine. (E) Mean values of change in [Ca2+]i during Ca2+ entry (700–800 s) and after removal of external Ca2+ (1200–1300 s) (n = 6 experiments from four animals, *P < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

In another set of experiment, we tested if RyR locked by ryanodine in a subconductance state40 can activate Ca2+ influx. A short 10 s-pulse of caffeine was applied to PASMCs pre-treated with (10 min) and in the continuous presence of 50 μmol/L ryanodine and 2 mmol/L Ca2+. The caffeine-pulse induced a Ca2+ transient with a peak followed by a sustained plateau phase (Δ[Ca2+]i: 69.9 ± 26.9 nmol/L, n = 6) (Figure 6D and E), which persisted long after caffeine was washed out. The plateau phase was abolished by the removal of external Ca2+ and was recovered after reintroduction of Ca2+, showing that it was exclusively caused by Ca2+ entry. The same caffeine-pulse in the absence of ryanodine activated comparable peak Ca2+ release, but failed to activate a sustained Ca2+ response. Collectively, these data suggest that depletion of RyR-gated store with caffeine alone is insufficient to induce RyR-gated Ca2+ entry, but requires a specific change of RyR conformation that can be achieved through ryanodine binding.

3.6. The I4827T mutation on RyR2 abolished RyR-gated Ca2+ entry

To further test the concept that ryanodine binding modifies RyR to allow activation of Ca2+ influx, wild-type RyR2 (WT) and RyR2-I4827T mutant was transfected into HEK293 cells. RyR2-I4827T is a ryanodine-binding deficient mutant, which was shown to have no detectable [3H] ryanodine binding.41 WT and the mutant RyR2-transfected cells had similar RyR2 expression level, which was 2–3 times higher than that of untransfected control HEK293 cells (n = 8–10, P < 0.05) (Figure 7A). Application of caffeine together with ryanodine or 4-CmC caused similar Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells transfected with RyR2-WT and RyR2-I4827T, but did not cause significant Ca2+ release in the untransfected control (Figure 7B). This indicated functional RyRs were expressed and the SR Ca2+ stores were comparable in the WT and mutant RyR overexpressed cells. In contrast, caffeine/ryanodine activated Ca2+ entry with an averaged peak of 97 ± 18 nmol/L in RyR2-WT transfected cells (n = 7), but the Ca2+ entry was minimal in RyR2-I4827T mutant cells (27 ± 4 nmol/L, n = 6; P < 0.05) (Figure 7C). Furthermore, 4-CmC activated a small SOCE in the RyR2-WT transfected cells, and the RyR-gated SOCE was significantly attenuated in the RyR2-I4827T-transfected cells (Δ[Ca2+]i of WT: 21 ± 3 nmol/L, n = 11; RyR2-I4827T: 3 ± 2 nmol/L, n = 8; P ≤ 0.001; Figure 7D). These data indicate that the I4827 residue of RyR is important for the gating of Ca2+ influx by the RyR-activating agents.

Figure 7.

Effect of RyR2-I4827T mutant on RyR-gated SOCE. (A) Western blot and normalized amount of RyR2 protein in control and HEK293 cells transfected with RyR2-wild-type (WT) or RyR2-I4827T mutant (n = 8–10, *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (B) Caffeine in the presence of ryanodine-activated Ca2+ release in RyR2-WT and RyR2-I4827T mutant-transfected HEK293 cells, but not in untransfected control. (Middle and right panels) Averaged peak change in [Ca2+]i activated by caffeine and 4-CmC, respectively, in control, WT, or mutant (n = 6–7, *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (C) Averaged Ca2+ traces showing Ca2+ entry activated by caffeine and ryanodine, and (D) by 4-CmC in HEK293 cells expressing RyR2-WT or RyR2-I4827T mutant (n = 6–11, *P < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

It is noted that 4-CmC activated a much smaller SOCE compared with caffeine and ryanodine in the RyR2-WT transfected HEK293 cells, despite Ca2+ release activated by both methods were similar. The reason for the discrepancy is unclear. A recent study suggested that 4-CmC may partially inhibit Orai-mediated Ca2+ entry,42 which could be an important component of SOCE in the HEK293 cells.

4. Discussion

The present study characterized the functional and molecular properties of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry in PASMCs. The major findings are (i) the RyR agonist 4-CmC is capable of activating RyR-gated Ca2+ influx; (ii) the RyR-gated Ca2+ influx is mediated mainly through RyR2; (iii) the physiological and pharmacological properties of RyR-gated Ca2+ influx is indistinguishable from SOCE activated by thapsigargin; (iv) depletion of RyR-sensitive Ca2+ store with caffeine alone is insufficient to activate Ca2+ influx; (v) addition of ryanodine together with caffeine restored RyR-gated Ca2+ influx without altering SR Ca2+ depletion; and (vi) mutation of the I4827 residual of RyR2 abolished RyR-gated Ca2+ entry. These results revealed the unique property of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry in rat PASMCs that its activation requires both depletion of RyR-gated Ca2+ stores and a specific change of RyR conformation.

This study provided the direct evidence that activation of RyR with 4-CmC is capable of stimulating Ca2+ influx in PASMCs. This is in concordance with the reports that depletion of RyR-gated Ca2+ stores contributes to SOCE in skeletal muscle, lymphocytes, and airway smooth muscle.5–8 This is also consistent with the observations that the endogenous RyR agonist cyclic-ADP-ribose (cADPR) activated Ca2+ influx in human myometrial cells and in RyR1 and TRPC3 co-expressing HEK293 cells; and the cADPR inhibitor 8-Br-cADPR attenuated Ca2+ influx induced by endothelin-1 in myometrial cells.7,15 However, it is in contrast to the early study in canine PASMCs that depletion of both InsP3R- and RyR-sensitive Ca2+ stores are required to elicit SOCE.30,31 Since vasoactive agonist was not used in our experiments and inhibition of InsP3R with xestospongin C did not affect RyR-mediated Ca2+ entry, our results clearly show that stimulation of RyR can independently activate SOCE in rat PASMCs.

RyR-gated Ca2+ influx in PASMCs is mediated by RyR2. It is deduced from the facts that the RyR1 and RyR2 agonist 4-CmC43,44 activated robust Ca2+ entry, but the RyR1 agonist maurocalcine32 failed to stimulate Ca2+ entry; and the RyR1 and RyR3 antagonist dantrolene33 had no effect, while K201 which stabilizes RyR234 abolished the 4-CmC induced Ca2+ influx. Our previous studies showed that all three RyRs are expressed in PASMCs with RyR2 being the predominant subtype.26 RyR2 is expressed in the peripheral SR close to the sarcolemmal membrane, RyR3 is localized in perinuclear regions, and RyR1 is expressed in both peripheral and perinuclear SR.26 The close proximity of RyR2-gated SR with plasma membrane is therefore essential for the SR–PM junctional interactions for RyR-gated Ca2+ entry. Recent studies from other groups showed RyR1 localization in the subsarcolemal regions of PASMCs,27,28 and may perform other physiological functions including interactions with stretch-activated cation channels in PM.28 It is noteworthy that the highly abundant RyR2s in the dyadic junctions of adult cardiac myocytes are not involved in SOCE despite InsP3R-gated SOCE is intact.9–11 Hence, the molecular compositions and functional properties of the SR–PM junctions of PASMCs and cardiac myocytes are clearly different despite their SRs are both gated by RyR2.

The RyR2-gated Ca2+ influx observed in the present study has similar pharmacological and molecular properties of conventional SOCE in PASMCs activated by depletion of SR using thapsigargin or cyclopiazonic acid. It was inhibited by lanthanides including Gd3+ and La3+, blocked by ML-9,36 and attenuated by siRNA knockdown of STIM1, TRPC1, and Orai1. The requirement of the SR Ca2+ sensor STIM1 in RyR-gated Ca2+ entry clearly indicates that it is indeed a component of SOCE in PASMCs.37,45,46 The participation of TRPC1 in SOCE is consistent with previous studies from several laboratories using TRPC1 specific siRNA,16 blocking antibody,45 and TRPC1 overexpression.17 Involvement of Orai1 in SOCE in PASMCs has also been established.37,46 However, RyR-gated Ca2+ entry in PASMCs can be distinguished from conventional SOCE, because depletion of RyR-gated Ca2+ stores alone is insufficient to activate Ca2+ influx. Continuous activation of RyRs with caffeine failed to stimulate Ca2+ influx despite [Ca2+]SR was reduced to the same level caused by 4-CmC. Furthermore, ryanodine, which itself does not activate SOCE, restores the ability of caffeine to induce Ca2+ influx without promoting Ca2+ release or causing further reduction of [Ca2+]SR. These results suggest that other factors in addition to SR depletion are required for the activation of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry.

The inability of caffeine to activate SOCE could not be explained by the interference of the STIM1, TRPC1, and/or Orai channels, because caffeine does not affect thapsigargin-induced SOCE in rat PASMCs. Rather, the differential effects of caffeine and 4-CmC on activating Ca2+ entry may underscore the importance of ligand-dependent conformational change of RyRs in the process. It is known that 4-CmC and caffeine bind to different sites of RyR.43,47 Substitution of specific residuals in the C-terminus of RyR that renders 4-CmC ineffective has no effect on caffeine-induced Ca2+ release. Caffeine and 4-CmC also induce different conformational changes of RyR.48,49 FRET-analysis of the interaction between the amino-terminal and the central region of RyR2 which is crucial for the channel gating showed that activation of RyR with caffeine enhanced, whereas 4-CmC and other physiological activators of RyR, including ATP and Ca2+, decreased the domain–domain interactions.48 Another study showed that caffeine caused conformational change in the clamp region of RyR2, but 4-CmC and Ca2+ did not.49 Hence, 4-CmC and other physiological activators may confer a RyR conformation that facilitates RyR-gated Ca2+ entry.

The notion of specific RyR conformational change is required for gating Ca2+ influx is supported by the restoration of caffeine-induced Ca2+ influx by ryanodine without causing further reduction of [Ca2+]SR. Ryanodine binds to opened RyRs and locks the channels in a stable subconductance state which presents a large energy barrier for RyR closing.40 Interestingly, it has been shown that ryanodine alone does not affect the N-terminal and the central domain interaction of RyRs, but the binding of ryanodine to RyR2 activated by caffeine reverts the domain–domain interaction in the direction similar to that induced by 4-CmC or by ATP and Ca2+.48 The conformational change of RyR induced by RyR and caffeine persisted after caffeine washout.48 This is coherent with our finding that ryanodine by itself does not activate RyR-gated SOCE in PASMCs, but ryanodine in the presence of caffeine activates Ca2+ influx similar to those elicited by 4-CmC. The persistent Ca2+ influx observed long after caffeine washout is also consistent with the stable binding of ryanodine maintains the RyR conformation required for Ca2+ influx. Furthermore, the abolition of caffeine/ryanodine-activated Ca2+ influx in the RyR2-I4827T overexpressed cells which exhibited normal caffeine/ryanodine-induced Ca2+ release provides supportive evidence that ryanodine binding facilitates RyR-gated Ca2+ entry independent of RyR activation and SR Ca2+ release.

The requirement of both SR Ca2+ depletion and conformational change of RyR for the induction of Ca2+ entry in PASMCs suggests physical association of RyR to the SOCE machinery. It has been shown that the foot-structure (N-terminus cytoplasmic domains) of heterologously expressed RyR1 is required for caffeine-induced Ca2+ entry in CHO cells.14 Co-immunoprecipitation of overexpressed RyR1 and TRPC3; and colocalization of the RyR2 and STIM1 had been reported in HEK293 cells.15,50 Our study also shows that substitution of RyR2-I4827 disrupts RyR-gated Ca2+ entry. These observations suggest conformational coupling involving RyR may be an essential step of RyR-gated SOCE. Conformational coupling was proposed previously as one of the models of InsP3R-gated SOCE,51 but the attention was shifted after the discovery of STIM1 in SOCE. It is proposed more recently that the Homer proteins may act as the physical link between InsP3R and TRPC channels keeping the channels in the closed state; and dissociation of the TRPCs–Homer–InsP3R complex allows STIM1 to access and gate-open the TRPC channels for Ca2+ entry.52,53 Since Homer proteins also bind and regulate RyRs,54,55 similar mechanism may participate in RyR-gated SOCE. Moreover, other RyR-associated proteins in the SR–PM junctional complex may be also involved. The intricate activation model of RyR-gated Ca2+ entry warrants further investigations.

RyR-gated SOCE may play specific roles in pulmonary vascular functions. Previous studies have established that SOCE is an important mechanism for the activation of HPV,18 which can be effectively blocked by inhibiting RyR-gated Ca2+ stores.21–23 RyR-gated SOCE can contribute to vasoactive agonist-induced Ca2+ response due to RyR activation by the endogenous RyR ligand cADPR and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release.20,29 Furthermore, SOCE is known to play an essential role in enhanced pulmonary vascular tone, PASMC proliferation and migration, and vascular remodelling during the development of pulmonary hypertension.16,19 However, it is unclear whether the RyR-gated and InsP3R-gated SOCE operate independently or interdependently in these specific physiological processes. In conclusion, the present study identified and characterized a unique mode of Ca2+ entry gated by ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores in PASMCs. Since SOCE and RyR-dependent Ca2+ pathways are known to play crucial roles in diverse vascular functions, new information on the mechanistic interactions between these two important processes may provide novel insights for the physiological and pathophysiological regulation of pulmonary and perhaps other vasculatures.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Funding

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health grants (R01 HL-075134 and HL-071835), and American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid to J.S.K.S.; and American Lung Association Senior Research Training Fellowship to A.H.Y.L.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr S.R. Wayne Chen, University of Calgary, for providing the RyR2-WT and RyR-I4827T mutant clones.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Putney JW. Capacitative calcium entry: from concept to molecules. Immunol Rev 2009;231:10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trebak M. STIM/Orai signalling complexes in vascular smooth muscle. J Physiol 2012;590:4201–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wray S, Burdyga T. Sarcoplasmic reticulum function in smooth muscle. Physiol Rev 2010;90:113–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabertrand F, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Ryanodine receptors, calcium signaling, and regulation of vascular tone in the cerebral parenchymal microcirculation. Microcirculation 2013;20:307–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan Z, Yang D, Nagaraj RY, Nosek TA, Nishi M, Takeshima H, Cheng H, Ma J. Dysfunction of store-operated calcium channel in muscle cells lacking mg29. Nat Cell Biol 2002;4:379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sei Y, Gallagher KL, Basile AS. Skeletal muscle type ryanodine receptor is involved in calcium signaling in human B lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 1999;274:5995–6002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson M, White T, Chini EN. Modulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry by cyclic-ADP-ribose. Braz J Med Biol Res 2006;39:739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ay B, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM, Sieck GC. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in porcine airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;286:L909–L917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uehara A, Yasukochi M, Imanaga I, Nishi M, Takeshima H. Store-operated Ca2+ entry uncoupled with ryanodine receptor and junctional membrane complex in heart muscle cells. Cell Calcium 2002;31:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohba T, Watanabe H, Murakami M, Sato T, Ono K, Ito H. Essential role of STIM1 in the development of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;389:172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins HE, Zhu-Mauldin X, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. STIM1/Orai1-mediated SOCE: current perspectives and potential roles in cardiac function and pathology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013;305:H446–H458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao X, Weisleder N, Han X, Pan Z, Parness J, Brotto M, Ma J. Azumolene inhibits a component of store-operated calcium entry coupled to the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem 2006;281:33477–33486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherednichenko G, Hurne AM, Fessenden JD, Lee EH, Allen PD, Beam KG, Pessah IN. Conformational activation of Ca2+ entry by depolarization of skeletal myotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:15793–15798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampieri A, Diaz-Munoz M, Antaramian A, Vaca L. The foot structure from the type 1 ryanodine receptor is required for functional coupling to store-operated channels. J Biol Chem 2005;280:24804–24815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiselyov KI, Shin DM, Wang Y, Pessah IN, Allen PD, Muallem S. Gating of store-operated channels by conformational coupling to ryanodine receptors. Mol Cell 2000;6:421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin MJ, Leung GP, Zhang WM, Yang XR, Yip KP, Tse CM, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of store-operated and receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells: a novel mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res 2004;95:496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunichika N, Yu Y, Remillard CV, Platoshyn O, Zhang S, Yuan JX. Overexpression of TRPC1 enhances pulmonary vasoconstriction induced by capacitative Ca2+ entry. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;287:L962–L969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sylvester JT, Shimoda LA, Aaronson PI, Ward JP. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Physiol Rev 2012;92:367–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y, Fantozzi I, Remillard CV, Landsberg JW, Kunichika N, Platoshyn O, Tigno DD, Thistlethwaite PA, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Enhanced expression of transient receptor potential channels in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:13861–13866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang WM, Yip KP, Lin MJ, Shimoda LA, Li WH, Sham JS. ET-1 activates Ca2+ sparks in PASMC: local Ca2+ signaling between inositol trisphosphate and ryanodine receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003;285:L680–L690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Ca2+ responses of pulmonary arterial myocytes to acute hypoxia require release from ryanodine and inositol trisphosphate receptors in sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012;303:L161–L168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connolly MJ, Prieto-Lloret J, Becker S, Ward JP, Aaronson PI. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in the absence of pretone: essential role for intracellular Ca2+ release. J Physiol 2013;591:4473–4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morio Y, McMurtry IF. Ca(2+) release from ryanodine-sensitive store contributes to mechanism of hypoxic vasoconstriction in rat lungs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002;92:527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng LC, Wilson SM, McAllister CE, Hume JR. Role of InsP3 and ryanodine receptors in the activation of capacitative Ca2+ entry by store depletion or hypoxia in canine pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Brit J Pharmacol 2007;152:101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson SM, Mason HS, Smith GD, Nicholson N, Johnston L, Janiak R, Hume JR. Comparative capacitative calcium entry mechanisms in canine pulmonary and renal arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 2002;543:917–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang XR, Lin MJ, Yip KP, Jeyakumar LH, Fleischer S, Leung GP, Sham JS. Multiple ryanodine receptor subtypes and heterogeneous ryanodine receptor-gated Ca2+ stores in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;289:L338–L348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark JH, Kinnear NP, Kalujnaia S, Cramb G, Fleischer S, Jeyakumar LH, Wuytack F, Evans AM. Identification of functionally segregated sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium stores in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 2010;285:13542–13549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert G, Ducret T, Marthan R, Savineau JP, Quignard JF. Stretch-induced Ca2+ signalling in vascular smooth muscle cells depends on Ca2+ store segregation. Cardiovasc Res 2014;103:313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang YL, Lin AH, Xia Y, Lee S, Paudel O, Sun H, Yang XR, Ran P, Sham JS. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) activates global and heterogeneous local Ca2+ signals from NAADP- and ryanodine receptor-gated Ca2+ stores in pulmonary arterial myocytes. J Biol Chem 2013;288:10381–10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun H, Xia Y, Paudel O, Yang XR, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of Ca2+-activated Cl- channel in pulmonary arterial myocytes: a mechanism contributing to enhanced vasoreactivity. J Physiol 2012;590:3507–3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen W, Wang R, Chen B, Zhong X, Kong H, Bai Y, Zhou Q, Xie C, Zhang J, Guo A, Tian X, Jones PP, O'Mara ML, Liu Y, Mi T, Zhang L, Bolstad J, Semeniuk L, Cheng H, Chen J, Tieleman DP, Gillis AM, Duff HJ, Fill M, Song LS, Chen SR. The ryanodine receptor store-sensing gate controls Ca2+ waves and Ca2+-triggered arrhythmias. Nat Med 2014;20:184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szappanos H, Smida-Rezgui S, Cseri J, Simut C, Sabatier JM, De Waard M, Kovacs L, Csernoch L, Ronjat M. Differential effects of maurocalcine on Ca2+ release events and depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol 2005;565:843–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao F, Li P, Chen SR, Louis CF, Fruen BR. Dantrolene inhibition of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels. Molecular mechanism and isoform selectivity. J Biol Chem 2001;276:13810–13816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Reiken SR, Deng SX, Vest JA, Cervantes D, Coromilas J, Landry DW, Marks AR. Protection from cardiac arrhythmia through ryanodine receptor-stabilizing protein calstabin2. Science 2004;304:292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacherer M, Sedej S, Wakula P, Wallner M, Vos MA, Kockskamper J, Stiegler P, Sereinigg M, von Lewinski D, Antoons G, Pieske BM, Heinzel FR. JTV519 (K201) reduces sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2)(+) leak and improves diastolic function in vitro in murine and human non-failing myocardium. Brit J Pharmacol 2012;167:493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Bird GS, Putney JW Jr. Ca2+-store-dependent and -independent reversal of Stim1 localization and function. J Cell Sci 2008;121:762–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogawa A, Firth AL, Smith KA, Maliakal MV, Yuan JX. PDGF enhances store-operated Ca2+ entry by upregulating STIM1/Orai1 via activation of Akt/mTOR in human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012;302:C405–C411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Mousa F, Michelangeli F. Commonly used ryanodine receptor activator, 4-chloro-m-cresol (4CmC), is also an inhibitor of SERCA Ca2+ pumps. Pharmacol Rep 2009;61:838–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon TR, Guo T, Bers DM. Ca2+ scraps: local depletions of free [Ca2+] in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum during contractions leave substantial Ca2+ reserve. Circ Res 2003;93:40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rousseau E, Smith JS, Meissner G. Ryanodine modifies conductance and gating behavior of single Ca2+ release channel. Am J Physiol 1987;253:C364–C368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao B, Masumiya H, Jiang D, Wang R, Sei Y, Zhang L, Murayama T, Ogawa Y, Lai FA, Wagenknecht T, Chen SR. Isoform-dependent formation of heteromeric Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors). J Biol Chem 2002;277:41778–41785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng B, Chen GL, Daskoulidou N, Xu SZ. The ryanodine receptor agonist 4-chloro-3-ethylphenol blocks ORAI store-operated channels. Br J Pharmacol 2014;171:1250–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fessenden JD, Perez CF, Goth S, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Identification of a key determinant of ryanodine receptor type 1 required for activation by 4-chloro-m-cresol. J Biol Chem 2003;278:28727–28735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choisy S, Huchet-Cadiou C, Leoty C. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) release by 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CmC) in intact and chemically skinned ferret cardiac ventricular fibers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999;290:578–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ng LC, McCormack MD, Airey JA, Singer CA, Keller PS, Shen XM, Hume JR. TRPC1 and STIM1 mediate capacitative Ca2+ entry in mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 2009;587:2429–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ng LC, Ramduny D, Airey JA, Singer CA, Keller PS, Shen XM, Tian H, Valencik M, Hume JR. Orai1 interacts with STIM1 and mediates capacitative Ca2+ entry in mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010;299:C1079–C1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fessenden JD, Feng W, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Amino acid residues Gln4020 and Lys4021 of the ryanodine receptor type 1 are required for activation by 4-chloro-m-cresol. J Biol Chem 2006;281:21022–21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Z, Wang R, Tian X, Zhong X, Gangopadhyay J, Cole R, Ikemoto N, Chen SR, Wagenknecht T. Dynamic, inter-subunit interactions between the N-terminal and central mutation regions of cardiac ryanodine receptor. J Cell Sci 2010;123:1775–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tian X, Liu Y, Wang R, Wagenknecht T, Liu Z, Chen SR. Ligand-dependent conformational changes in the clamp region of the cardiac ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem 2013;288:4066–4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thakur P, Dadsetan S, Fomina AF. Bidirectional coupling between ryanodine receptors and Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel machinery sustains store-operated Ca2+ entry in human T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 2012;287:37233–37244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Putney JW Jr, Broad LM, Braun FJ, Lievremont JP, Bird GS. Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry. J Cell Sci 2001;114:2223–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan JP, Kiselyov K, Shin DM, Chen J, Shcheynikov N, Kang SH, Dehoff MH, Schwarz MK, Seeburg PH, Muallem S, Worley PF. Homer binds TRPC family channels and is required for gating of TRPC1 by IP3 receptors. Cell 2003;114:777–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan JP, Lee KP, Hong JH, Muallem S. The closing and opening of TRPC channels by Homer1 and STIM1. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2012;204:238–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Westhoff JH, Hwang SY, Duncan RS, Ozawa F, Volpe P, Inokuchi K, Koulen P. Vesl/Homer proteins regulate ryanodine receptor type 2 function and intracellular calcium signaling. Cell Calcium 2003;34:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pouliquin P, Dulhunty AF. Homer and the ryanodine receptor. Eur Biophys J 2009;39:91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]