Abstract

Integrons are genetic elements capable of capturing and expressing open reading frames (ORFs) embedded within gene cassettes. They are involved in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in clinically important pathogens. Although the ARGs are common in the oral cavity the association of integrons and antibiotic resistance has not been reported there. In this work, a PCR-based approach was used to investigate the presence of integrons and associated gene cassettes in human oral metagenomic DNA obtained from both the UK and Bangladesh. We identified a diverse array of gene cassettes containing ORFs predicted to confer antimicrobial resistance and other adaptive traits. The predicted proteins include a putative streptogramin A O-acetyltransferase, a bleomycin binding protein, cof-like hydrolase, competence and motility related proteins. This is the first study detecting integron gene cassettes directly from oral metagenomic DNA samples. The predicted proteins are likely to carry out a multitude of functions; however, the function of the majority is yet unknown.

Introduction

Integrons are commonly found in bacterial genomes, especially in most Gram-negative bacteria. They are involved in the dissemination and differential expression of genes in the bacterial population [1–3]. They contain two common features, a functional platform and an array of gene cassettes (GCs). The former or the 5’ conserved segment (5’CS) contains the integrase gene, intI, an attI recombination site and the promoter Pc. This platform is used for the capturing and expression of the GCs, non-replicative mobile elements which generally couple one or more open reading frames (ORFs) with the cassette-associated recombination attC site. The intI gene encodes a site-specific tyrosine recombinase, IntI which catalyses the integration and excision of the GCs. The expression of integrase genes can be upregulated by the SOS response, a bacterial stress response induced by the accumulation of single stranded DNA in a cell, such as transformation, conjugation, starvation and exposure to antibiotics such as quinolones and trimethoprim [4].

The recombination usually occurs between attI, located immediately adjacent to intI, and attC which is present on circular gene cassettes [5–7]. The attC sites contain two inverted regions of homology (L’-R’ and R”-L”), which flank the central region containing a highly variable sequence. The size of attC can be between 57 to 141 bp [8]. Even though the sequences of attC sites are not conserved, they show a palindromic organization which is essential for the formation of the correct hairpin structure, which is the recognition site of the integrase during integron GC recombination reactions [9]. The GCs normally do not have a promoter. The Pc promoter is usually required for the transcription of GC ORFs, therefore the first GC following Pc often has the higher levels of expression relative to downstream GC located ORFs [10].

Integrons have the potential to drive bacterial evolution and adaptation by differential expression of ORFs within GCs. One of the most clinically significant adaptive traits is antibiotic resistance [11]. The first integrons were identified by their association with antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [12]. Among hundreds of classes of integrons, class 1 integrons are the most commonly associated with multiple ARGs in clinical strains. More than 130 different GCs carried by integrons were predicted to confer resistance to a variety of classes of antibiotics such as aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, and streptothricin [13].

Gene cassettes are abundant and disseminated widely in diverse environments. Different isolates of the same bacterial species can have different GC arrays [14]. The predicted protein functions of ORFs within GCs are varied and include, in addition to antibiotic resistance, virulence, and secondary metabolism, which are likely to be niche-specific [1, 2]. However, metagenomic analyses of the integron cassette gene pool from several studies revealed that vast majority of GCs were novel [15–17].

Due to the fact that, in many environments, less than 1% of the bacterial population is culturable [18], one of the approaches to investigate the GCs in the entire bacterial community is the PCR-based amplification of GCs using metagenomic DNA as a template [19]. Several studies on the diversity of GCs in different environments have been performed with this approach such as soil, seawater, marine sediment and deep sea vents [16, 17, 19, 20].

The human oral cavity is one of the most complex microbial ecosystems in the human body. More than 700 bacterial species have been detected from the oral cavity, [21, 22]. Many ARGs have been detected and discovered in the oral cavity, including tetracycline resistance genes tet(Q), tet(W), tet(M), tet(37) and tet(32); erythromycin resistance genes, ermB and mef, and kanamycin resistance gene, aphA-3 [23–25]. Recent genetic analysis of the oral metagenome showed that 2.8% of the predicted genes had the potential to encode proteins with antibiotic and toxin resistance [26]. However, very few studies investigating integrons in human oral cavity have been performed. There are two major reports on integrons in the human oral cavity; one describing an unusual or reverse integron, an integron with the integrase gene oriented in the same direction as a gene cassette array, in Treponema denticola ATCC35405 by using whole genome sequencing analysis, and the in silico analysis of an integron associated with Treponema species by using metagenomic datasets of the Human Microbiome Project [14, 27]. The presence of other integrons in other oral bacterial species remains to be determined.

Despite the oral microbiota being recognised as a potential source of ARGs and the oral environment providing conducive conditions for the transfer of ARGs between a range of species [25], no in depth studies have been carried out to detect integrons and GCs within the oral microbiota. In this study, we have investigated the presence of integrons and associated GCs in the human oral metagenomic DNA from two countries, the UK and Bangladesh using a PCR approach. Different sets of primers targeting different regions of integrons were used for PCR amplification, in which multiple GCs were identified and predicted to encode various proteins including some likely to confer antibiotic resistance.

Materials and Methods

Saliva sample collection and ethical approval

Saliva samples were collected from 11 and 10 healthy volunteers (both male and female with age between 21 and 65) from UK and Bangladesh, respectively. The UK samples were collected from the staff and international postgraduate students from the UCL Eastman Dental Institute and represent various ethnic and cultural backgrounds including Asian, Australian, European, African and Middle-Eastern, some of which had moved to the UK in the past few months. Therefore, the UK samples represent an international metagenome. The Bangladeshi samples were collected from the staff, undergraduate and post-graduate students of Department of Pharmacy of Rajshahi University all of which were Bangladeshi. All of the volunteers read and gave written consents before sample collection. None of the volunteers had received antibiotic treatment for 3 months before the sample collection day. Ethical approvals for the analysis of pooled saliva as part of this project were obtained from University College London (UCL) Ethics Committee (project number 5017/001) and the Institutional Animal, Medical Ethics, Biosafety and Biosecurity Committee (IAMEBBC) for Experimentations on Animal, Human, Microbes and Living Natural Sources, University of Rajshahi (project number 54/320/IAMEBBC/IBSC). Both ethics committees approved the consent procedures for the sample collection and processing. For the UK samples, 2 ml of saliva were collected in a sterile plastic tube and processed immediately. The samples from Bangladesh were collected and transported using Norgen’s Saliva DNA Collection and Preservation Device, (Norgen, Canada) following the manufacturer’s guidelines, and transported to UK for analysis. All samples were anonymised.

Extraction of oral metagenomic DNA

The freshly collected UK saliva samples were pooled together into a sterile plastic tube in a class I microbiological safety cabinet. The pooled saliva sample was then divided into 1.5ml aliquots and centrifuged at 20238 g for 1 min. The UK oral metagenomic DNA was then extracted by using the Puregene DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, UK), following the Gram-positive bacteria and yeasts protocol with the modification in final step, which the DNA pellets were dissolved in 400μL molecular grade water at room temperature, instead of 100μL.

The Bangladeshi oral metagenomic DNA was extracted from the Norgen’s Saliva DNA storage buffer using ethanol precipitation technique according to manufacturer’s protocol. The preservative buffer of Norgen devices is designed for rapid cellular lysis and subsequent preservation of DNA from fresh saliva samples. Prior to DNA isolation, the storage devices were incubated for 1h at 50°C and mixed by inversion and gentle shaking for 10 seconds. DNA was then extracted from 500 μL of the pooled saliva in preservative buffer by taking 50 μL aliquots from 10 saliva samples.

PCR amplification

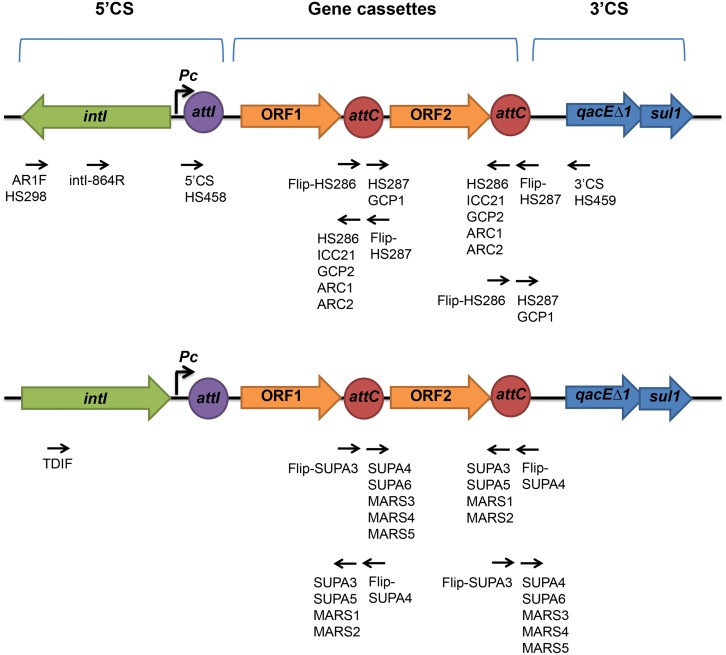

The list of primers and their sequences are shown in S1 Table and the target sites for the primers are shown in Fig 1. The typical PCR was prepared as follows; 50 μL reaction containing 15μl of 2x BioMix Red (Bioline, UK), 0.2 μM of each 10 μM primer, 50–100 ng of DNA template, and molecular grade water (Sigma, UK) up to 30 μL. The standard PCR was carried out with (i) an initial denaturation: 94°C for 5 minutes, (ii) denaturation step: 94°C for 1 minute, (iii) annealing step: 50–65°C depending on the primers for 30 seconds, (iv) elongation step: 72°C for 30 seconds to 3 minutes depending on the size of expected products, repeated step (ii)-(iv) for 35 cycles and (v) final elongation step 72°C for 10 min.

Fig 1. The primer binding sites of the published and newly designed primers.

Primers were indicated as black arrows on A.) the class 1 integrons and B.) the unusual integron structure of T. denticola. The open arrowed boxes represent ORFs, pointing in the probable direction of transcription. The genes in 5’and 3’ conserved segment (CS), the open reading frame (ORF), the recombination site attI and attC are shown in grey, blue, green, yellow and orange respectively.

PCR purification and gel extraction

The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel stained with 1:10,000 dilution of GelRed nucleic acid stain (Biotium, UK). The products were then purified by using either QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, UK) or QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, UK), depending on the amplification results and the target amplicons, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Ligation and transformation

Purified PCR products were ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, UK). The ligation mixtures were transformed into Escherichia coli α-Select Silver Efficiency competent cells (Bioline, UK) by heat shock at 42°C for 40 s, and plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) as a selective marker for the plasmids and 40 μg/ml X-Gal plus 0.4 mM IPTG for the blue-white colony screening.

Plasmid isolation and sequencing

White colonies were subcultured in 5 mL of LB broth with ampicillin (100μg/mL) and incubated overnight. Plasmids were isolated by using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The presence of the insert in a plasmid was verified by a 10μl DNA digestion reaction, containing 0.5 μL EcoRI restriction enzyme (20 units/μL, New England Biolabs, UK), 1μL 10x EcoRI buffer, 100–500 ng of DNA and molecular grade water (Sigma, UK) up to 10 μL. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour and electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel.

Sequence analyses

DNA sequencing of inserts were performed at the Beckman Coulter Genomics (Beckman Coulter Genomics, UK) with an ABI 3730XL. M13 forward (5’ GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC 3’) and M13 reverse (5’ GGAAACAGCTATGACCATG 3’) primers were used as the initial primers for sequencing. Additional primers were designed and used for further sequencing for the longer inserts using Primer3 (http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi).

DNA sequences were aligned and manipulated by using BioEdit software version 7.2.0 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html). For the inserts which required sequencing with more than one primer, the sequences were assembled using the CAP contig function in the BioEdit program [28]. The sequences were screened for vector contamination by using VecScreen analysis tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/vecscreen). The primer binding sites were then identified by searching the sequences by eye. The sequences were analysed by the comparison of sequence and translated sequence using the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) tools and databases including BlastN and BlastX [29], ORF finder and Clustal Omega.

A sequence obtained using the attC-based primers was considered a putative GCs if (i) it contains both of the primer sequences (designed from conserved nucleotides of attC) (ii) the sites included an integrase-like simple site at each end [10] (iii) the primer sites flank a putative ORF beginning with ATG, TTG or GTG [17]. The sequences which did not contain an ORF, but contained the attC site, were considered as empty GCs. The putative translated sequences were subjected to BlastX searches and matches were considered significant if the e-value was <0.001.

Nomenclature and accession number of the gene cassettes

The gene cassettes (GCs) were named according to the source and the primers. The first two letters indicate the forward and reverse primers used for amplification. The third letter indicates the source of oral metagenomic DNA that the GCs amplified from (U for UK; B for Bangladesh), which is followed by a numerical code for the number of clone. For example, TMB1 means it is the first GC obtained from Bangladeshi samples by using the primer TDIF and MARS2.

The sequences of integron regions, which contained intI, Pc, attI and gene cassettes, were deposited in the DNA database Genbank under accession numbers from KT921469 to KT921473. The accession numbers from KT921474 to KT921509 and from KT921510 to KT921531 represented gene cassette sequences generated by the T. denticola primers from UK and Bangladeshi samples, respectively.

Results

Recovery and characterization of PCR products containing intI and the first gene cassette

Initially, we used previously published primers that had been used to successfully amplify gene cassettes from a range of environments (Fig 1, S1 and S2 Tables). Unexpectedly none of these primers produced amplicons having the structural features of a gene cassette [17] when oral metagenomic DNA isolated from the UK and Bangladesh was used as a template (see materials and methods).

As Treponema denticola integrons are the only ones that have been described in the oral microbiota [27], new primers were designed based on this integron. The PCR were performed by using the intI-based primer TDIF (designed based on the conserved amino acid sequence SSQNQAL of IntI of the Treponema denticola integron) coupled with the attC-based primer MARS2. Resulting amplicons were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector and a total of 17 clones were randomly selected from both cohorts and the inserts within the plasmids were sequenced. All of these contained the basic features of an integron. Within the amplicons, a major part of intI (768 bp), the full length attI site and a putative integron promoter, Pc were detected. A total of 5 different amplicons containing 5 different GCs including one empty GC with no identifiable ORF were found (Fig 2). The putative ORFs detected on the GCs had a size range of 258 to 777 bp (Table 1).

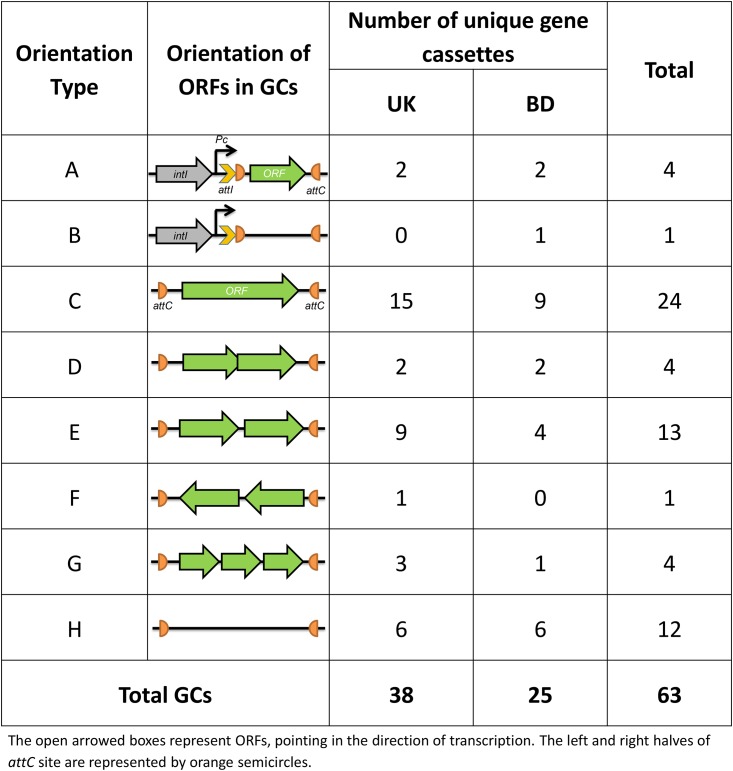

Fig 2. Orientation of ORFs in the GCs recovered from metagenomic DNA of saliva samples.

Table 1. Characterization of all gene cassettes detected in the saliva metagenomic DNA from UK and Bangladesh using TDIF and MARS2 primer combination to detect the first gene cassette.

| BlastN (ORF of first gene cassette) | BlastX (ORF of first gene cassette) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene cassettes /clone code | Primer pair | Size of insert including the integrase gene and first cassette (bp) | Orientation type | Distance between integrase gene and ORF of first gene cassette (bp) | Accession number | Closest homologue | Percentage identity (%) | Coverage (%) | Closest homologue | ORF size (bp) | Percentage identity (%) | Coverage (%) | The presence of ribosomal binding site | Accession number of the homologous proteins (BlastX) |

| TMB1/8/12/15 | TDIF-MARS2 | 1499 | A | 271 | KT921469 | No significant similarity | - | - | No significant similarity | 258 | - | - | Yes | - |

| TMB3/5/6/10/11/13/14/16 | TDIF-MARS2 | 1757 | A | 198 | KT921470 | Treponema putidum | 98 | 100 | Cof-like hydrolase [Treponema denticola] | 768 | 96 | 100 | Yes | WP_016512123 |

| TMB4 | TDIF-MARS2 | 1244 | B | - | KT921471 | Treponema pedis | 82 | 46 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TMU3/4/11 | TDIF-MARS2 | 1775 | A | 204 | KT921472 | Treponema sp. OMZ 838 | 77 | 97 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 777 | 99 | 100 | Yes | WP_002678613.1 |

| TMU18 | TDIF-MARS2 | 1692 | A | 161 | KT921473 | No significant similarity | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 387 | 100 | 100 | Yes | WP_002689012.1 |

Among the 17clones sequenced from both cohorts, 8 clones (TMB3/5/6/10/11/13/14/16) had a GC having an ORF (768-bp) predicted to encode a protein homologous to a cof-like hydrolase of Treponema putidum. Two of the first gene cassettes with an ORF of 258-bp and 387-bp present on clones TMB1/8/12/15 and TMU18, respectively had no nucleotide sequence similarity to anything in GenBank. However, at the amino acid level the 387-bp ORF on TMU18 showed 100% identity with a hypothetical protein of T. denticola. Another GC detected on clones TMU3/4/11 with an ORF of 777-bp was found to encode a hypothetical protein of Treponema denticola (Table 1). Finally, an empty first GC was found on clone TMB4.All but one ORF detected on the first GCs had putative ribosomal binding sites (RBS) at less than 8-bp upstream of the ORFs. In all first gene cassettes, two putative integrase binding sites (L and R; also termed as S2 and S1, respectively) were detected on the attI sites where the integrase binding sites S1 (R) were found to contain a plausible attI-attC junction (GTT). The 7 bp core site Rʹʹ (1L) of attC was also detected upstream of the reverse MARS2 primer having the consensus sequence RYY(/R)YAAC (S3 Table). In most cases, the stop codons of the ORFs was located at these Rʹʹ integrase binding sites of attC [8, 30].

Gene Cassettes Amplified Using attC-based primers

A library of PCR amplicons obtained using a different set of attC-based primers was constructed in pGEM-T Easy vector and the inserts from 100 clones were sequenced (Table 2, Fig 1, S1 and S2 Tables). By analysing the sequences with different bioinformatics tools we have detected a total of 58 unique GCs having the features of an integron GC and flanked by the primer binding sites. The size of the cassettes ranged from 425 to 1144 bp. Of the 58 GCs, 12 had no identifiable ORFs and the remaining 46 GCs contained one or more putative ORFs giving a total of 72 different ORFs with a size range between 117 to 894 bp. As the forward and reverse primers were designed based on the consensus Lʹ (2R) and Lʹʹ (2L) core sites, respectively, we were able to locate the Rʹ (1R) core sites in all GCs with a consensus GTTRR(Y)R(Y)Y(R) after the forward primer sequence. The complementary Rʹʹ (1L) core sites with a consensus R(Y)Y(R)Y(R)YAAC were also detected upstream or as a part of the reverse attC primers which confirms that the putative GCs are not PCR artefacts and is consistent with the attC structure of a GC [31]. The majority of the Rʹ and Rʹʹ core sites (51 out of 58 GCs) exhibited 100% complementarity with each other. In the remaining seven, 6 out of 7-bp were complimentary (S4 Table).

Table 2. Characterization of all gene cassettes detected in the saliva metagenomic DNA from UK and Bangladesh using attC-based primers.

| BlastN | BlastX | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene cassettes/clone code | Primer pair | Cassette Size (bp) | Orientation type | Distance between attC and ORF (bp) | Accession number | Closest homologue | Percentage identity (%) | Coverage (%) | Closest homologue | ORF size (bp) | Percentage identity (%) | Coverage (%) | The presence of ribosomal binding site | Accession number of the homologous proteins (BlastX) |

| SSU1/2, MMU15 | SUPA3-SUPA4, MARS5-MARS2 | 799 | C | 36 | KT921474 | No significant similarity found. | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Rhodonellum psychrophilum] | 579 | 66 | 75 | Yes | WP_026333632.1 |

| SSU3/4/30 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 964 | E | 41 | KT921475 | No significant similarity found. | - | - | Glyoxalase [Treponema pedis] | 390 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_009105863.1 |

| Competence protein TfoX [Treponema pedis] | 315 | 83 | 100 | Yes | WP_024470244.1 | |||||||||

| SSU5 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 832 | E | 136 | KT921476 | Treponema sp. | 88 | 27 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema putidum] | 243 | 67 | 100 | Yes | WP_044978234.1 |

| Twitching motility protein PilT [Treponema putidum] | 396 | 71 | 100 | Yes | AIN93467.1 | |||||||||

| SSU6 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 1138 | E | 34 | KT921477 | No significant similarity found. | - | - | No significant similarity found. | 459 | - | - | Yes | - |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 339 | 75 | 100 | Yes | WP_044013590.1 | |||||||||

| SSU7 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 491 | F | 0 | KT921478 | Treponema denticola | 92 | 40 | No significant similarity found | 162 | - | - | No | - |

| No significant similarity found | 132 | - | - | Yes | - | |||||||||

| SSU8 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 921 | C | 41 | KT921479 | Treponema sp. | 98 | 49 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 567 | 98 | 93.7 | Yes | WP_002692239.1 |

| SSU9/13/14/19/20/23 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 425 | H | - | KT921480 | Treponema pedis | 78 | 69 | No significant similarity found | - | - | - | - | - |

| SSU10 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 612 | C | 29 | KT921481 | No significant similarity found. | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Paenibacillus assamensis] | 537 | 39 | 91 | Yes | WP_028595336 |

| SSU11 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 648 | C | 4 | KT921482 | No significant similarity found. | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Bradyrhizobium sp. STM 3809] | 597 | 42 | 89.7 | Yes | WP_035659994.1 |

| SSU12 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 736 | C | 77 | KT921483 | No significant similarity found. | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Treponema vincentii] | 582 | 99 | 100 | Yes | WP_016518887.1 |

| SSU15 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 989 | G | 105 | KT921484 | Treponema denticola | 90 | 19 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema sp.] | 396 | 40 | 44.3 | Yes | WP_044015417.1 |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 228 | 39 | 16.4 | No | WP_010689034.1 | |||||||||

| Hypothetical protein TPE_0657 [Treponema pedis] | 147 | 96 | 100 | Yes | AGT43153.1 | |||||||||

| SSU16 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 711 | E | 127 | KT921485 | Treponema pedis | 90 | 21 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema sp.] | 363 | 33 | 41.6 | Yes | WP_044015417.1 |

| Hypothetical protein TPE_0657 [Treponema pedis] | 147 | 96 | 100 | Yes | AGT43153.1 | |||||||||

| SSU17 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 787 | C | 30 | KT921486 | Treponema denticola | 98 | 100 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 711 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_002690335.1 |

| SSU18 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 853 | C | 31 | KT921487 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein (Endonuclease) [Treponema putidum] | 765 | 33 | 99.2 | Yes | WP_044978378.1 |

| SSU21 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 871 | D | 273 | KT921488 | Treponema denticola | 97 | 100 | Toxin [Treponema denticola] | 291 | 96 | 100 | No | WP_010692226.1 |

| Hypothetical protein (antitoxin) [Treponema denticola] | 258 | 100 | 100 | Yes | WP_010692225.1 | |||||||||

| SSU22 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 1017 | E | 72 | KT921489 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Prevent-host-death family protein [Treponema medium] | 264 | 94 | 100 | Yes | WP_016523165.1 |

| XRE family transcriptional regulator [Treponema vincentii] | 441 | 96 | 100 | Yes | WP_006188306.1 | |||||||||

| SSU24 | SUPA3-SUPA4 | 962 | E | 23 | KT921490 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Glyoxalase [Treponema pedis] | 411 | 97 | 100 | No | WP_024470245.1 |

| Competence protein TfoX [Treponema pedis] | 222 | 88 | 55.2 | No | WP_024470244.1 | |||||||||

| SSU25 | SUPA5-SUPA6 | 789 | C | 31 | KT921491 | Treponema putidum | 96 | 99 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 705 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_010697531.1 |

| SSU26 | SUPA5-SUPA6 | 848 | C | 34 | KT921492 | Treponema putidum | 81 | 93 | Cof-like hydrolase [Treponema denticola] | 768 | 76 | 100 | Yes | WP_010693073.1 |

| SSU27 | SUPA5-SUPA6 | 833 | G | 155 | KT921493 | Treponema denticola | 96 | 100 | No significant similarity found | 126 | - | - | - | - |

| Antitoxin HicB [Treponema denticola] | 405 | 99 | 100 | No | WP_002669522.1 | |||||||||

| Toxin HicA [Treponema denticola] | 195 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_002669524.1 | |||||||||

| SSU28 | SUPA5-SUPA6 | 927 | E | 310 | KT921494 | Treponema putidum | 97 | 91 | Multidrug transporter MatE [Treponema putidum] | 336 | 96 | 100 | Yes | WP_044979179.1 |

| mRNA-degrading endonuclease [Treponema denticola] | 231 | 99 | 100 | Yes | WP_010694033.1 | |||||||||

| SSU29 | SUPA5-SUPA6 | 425 | H | - | KT921495 | Treponema pedis | 78 | 69 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMU2 | MARS5-MARS2 | 519 | H | - | KT921496 | Treponema denticola | 81 | 72 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMU3 | MARS5-MARS2 | 826 | C | 63 | KT921497 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Morganella morganii] | 753 | 32 | 97.13 | Yes | WP_036423270.1 |

| MMU7 | MARS5-MARS2 | 765 | C | 148 | KT921498 | Treponema denticola | 96 | 98 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema sp.] | 390 | 100 | 100 | Yes | WP_002688988.1 |

| MMU9/13 | MARS5-MARS2 | 725 | C | 127 | KT921499 | Treponema denticola | 90 | 21 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema phagedenis] | 474 | 53 | 98.8 | Yes | WP_044634793.1 |

| MMU11 | MARS5-MARS2 | 734 | H | - | KT921500 | Treponema pedis | 79 | 51 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMU18 | MARS5-MARS2 | 690 | C | 174 | KT921501 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 459 | 97 | 100 | Yes | EGC77532.1 |

| MMU19 | MARS5-MARS2 | 431 | H | - | KT921502 | Treponema pedis | 78 | 63 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMU20 | MARS5-MARS2 | 943 | C | 72 | KT921503 | Treponema putidum | 84 | 16 | No significant similarity found | 780 | - | - | No | - |

| MMU24 | MARS5-MARS2 | 1041 | D | 435 | KT921505 | Treponema sp. OMZ 838 | 97 | 62 | Plasmid maintenance system killer protein [Treponema sp. OMZ 838] | 279 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_044013090.1 |

| Hig A family addiction module antidote protein [Treponema socranskii] | 315 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_016519833.1 | |||||||||

| MMU25 | MARS5-MARS2 | 1144 | G | 61 | KT921506 | Treponema sp. OMZ 838, | 79 | 43 | No significant similarity found | 462 | - | - | Yes | - |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema maltophilum] | 213 | 91 | 91 | Yes | WP_016526060.1 | |||||||||

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema vincentii] | 351 | 77 | 100 | Yes | WP_044013590.1 | |||||||||

| MMU26 | MARS5-MARS2 | 972 | C | 27 | KT921507 | Treponema denticola | 95 | 100 | Carbon-nitrogen hydrolase [Treponema denticola] | 891 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_044901990.1 |

| MMU27 | MARS5-MARS2 | 896 | E | 38 | KT921508 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 402 | 95 | 88 | Yes | WP_002687406.1 |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 360 | 99 | 100 | Yes | WP_002673043.1 | |||||||||

| MMU28 | MARS5-MARS2 | 987 | E | 320 | KT921509 | Treponema putidum | 89 | 76 | Prevent-host-death protein [Treponema putidum] | 282 | 91 | 100 | Yes | WP_044979047.1 |

| Hypothetical protein (Plasmid stabilization protein) [Treponema putidum] | 213 | 85 | 99.1 | Yes | AIN94307.1 | |||||||||

| MMU23 | MARS5-MARS2 | 634 | H | - | KT921504 | Treponema pedis | 84 | 60 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMB1/2 | MARS5-MARS2 | 633 | H | - | KT921510 | Treponema pedis | 80 | 56 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMB3/9 | MARS5-MARS2 | 846 | C | 369 | KT921511 | Treponema sp. | 27 | 86 | Twitching motility protein PilT [Treponema putidum] | 414 | 70 | 89 | No | AIN93467.1 |

| MMB5/35 | MARS5-MARS2 | 423 | H | - | KT921513 | Treponema denticola | 84 | 94 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMB4/12/31 | MARS5-MARS2 | 877 | D | 271 | KT921512 | Treponema denticola | 96 | 100 | Toxin [Treponema denticola] | 288 | 95 | 100 | No | WP_01069226.1 |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema pedis] | 258 | 99 | 100 | Yes | WP_024468276.1 | |||||||||

| MMB11/13/21/25/29 | MARS5-MARS2 | 629 | C | 98 | KT921514 | Treponema denticola | 98 | 81 | Membrane protein [Treponema denticola] | 312 | 94 | 100 | Yes | WP_002669840.1 |

| MMB15 | MARS5-MARS2 | 889 | C | 31 | KT921516 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Mariprofundus ferrooxydans] | 804 | 46 | 89 | Yes | WP_009850619 |

| MMB22 | MARS5-MARS2 | 854 | C | 160 | KT921521 | Clostridium sp. | 74 | 43 | Vat family streptogramin A O- acetyltransferase [Treponema denticola] | 645 | 99 | 100 | Yes | WP_00267814.1 |

| MMB14 | MARS5-MARS2 | 862 | E | 86 | KT921515 | Treponema putidum | 66 | 97 | RelB/DinJ antitoxin [Treponema putidum] | 417 | 97 | 95 | Yes | WP_044978223 |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema vincentii] | 300 | 86 | 100 | Yes | WP_016519648.1 | |||||||||

| MMB17 | MARS5-MARS2 | 838 | E | 49 | KT921517 | Treponema denticola | 99 | 100 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 396 | 98 | 100 | Yes | WP_010957066.1 |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema putidum] | 117 | 100 | 100 | Yes | WP_010957065.1 | |||||||||

| MMB18 | MARS5-MARS2 | 792 | C | 26 | KT921518 | Treponema putidum | 98 | 100 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 708 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_010697531.1 |

| MMB19 | MARS5-MARS2 | 817 | C | 45 | KT921519 | Treponema denticola | 94 | 100 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 708 | 96 | 100 | Yes | WP_010697511.1 |

| MMB20 | MARS5-MARS2 | 531 | H | - | KT921520 | Treponema pedis | 80 | 66 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMB23/27 | MARS5-MARS2 | 901 | D | 283 | KT921522 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Peptidase (Antitoxin) [Treponema denticola] | 243 | 63 | 100 | Yes | WP_002667901.1 |

| PemK toxin [Treponema denticola] | 330 | 77 | 100 | Yes | WP_002680107.1 | |||||||||

| MMB28 | MARS5-MARS2 | 543 | C | 122 | KT921523 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Clostridium drakei] | 360 | 62 | 98 | Yes | WP_029160182.1 |

| MMB30 | MARS5-MARS2 | 808 | C | 25 | KT921524 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Treponema medium] | 729 | 92 | 100 | Yes | WP_016670455 |

| MMB32 | MARS5-MARS2 | 632 | H | - | KT921525 | Treponema pedis | 79 | 56 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMB33 | MARS5-MARS2 | 810 | E | 80 | KT921526 | Treponema denticola | 99 | 100 | Hypothetical protein [Treponema denticola] | 372 | 98 | 100 | No | WP_002689013.1 |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema sp.] | 276 | 99 | 100 | Yes | WP_002689021.1 | |||||||||

| MMB34 | MARS5-MARS2 | 714 | C | 120 | KT921527 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Treponema medium] | 525 | 94 | 99 | Yes | WP_016522334.1 |

| MMB36 | MARS5-MARS2 | 732 | H | - | KT921528 | Treponema pedis | 79 | 48 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMB37 | MARS5-MARS2 | 635 | H | - | KT921529 | Treponema denticola | 82 | 60 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MMB38 | MARS5-MARS2 | 947 | G | 3 | KT921530 | Treponema sp. | 97 | 67 | No significant similarity found | 201 | - | - | No | - |

| HigA antitoxin [Treponema socranskii] | 282 | 98 | 100 | Yes | WP_016519833.1 | |||||||||

| Plasmid maintenance system killer protein [Treponema medium] | 318 | 97 | 100 | Yes | WP_040858928.1 | |||||||||

| MMB39 | MARS5-MARS2 | 857 | E | 97 | KT921531 | No significant similarity found | - | - | Hypothetical protein [Treponema medium] | 357 | 96 | 100 | Yes | WP_016522532.1 |

| Hypothetical protein [Treponema medium] | 330 | 95 | 100 | Yes | WP_016522533.1 | |||||||||

By analysing the arrangement of genetic features within the GCs we found that they were arranged in seven different ways (Fig 2) as defined by the direction, position and number of ORFs within the GCs. The type C arrangement accounted for the majority; found in 24 cassettes. The sequences of the clones containing two or more ORFs were examined for the presence of other putative attC sequences in between the ORFs, none of which were found. These observations show that the attC-based primers based on the T. denticola integron are able to amplify GCs from oral metagenomic DNA. From 72 putative ORFs found in all GCs, 63 of them had ribosomal binding sites located upstream of the predicted start codons. As in previous studies the GCs other than the toxin-antitoxin encoding GCs did not contain an identifiable promoter, thus are likely to be dependent on the Pc of the cassette array for expression [19].

Diversity of the functions of putative proteins encoded by ORFs within the GCs detected by attC primers

Out of 72 putative ORFs detected on 58 different GCs amplified by using attC primers, 66 (91.66%) of the predicted proteins had a homologue in GenBank. However, only 24 of the 66 ORFs (36.36%) were found to encode proteins with known function and the remaining 42 matched hypothetical proteins. With regards to sequence similarity of the ORFs with those in GenBank, we found that 45 of the 66 ORFs (68.0%) exhibited >90% amino acid identity. Ten putative ORFs were predicted to encode completely novel proteins (e-value <0.001).

The putative ORFs detected on the gene cassettes were predicted to encode proteins of diverse functions including antibiotic resistance, host adaptation to stress and competence (Table 2). Four different putative antibiotic resistance genes were found among the cassette ORFs. BlastX searches showed that the clone MMB22 contained an ORF that encoded a protein with 99% identity to streptogramin A O-acetyltransferase from T. denticola. The single ORF (390-bp) present in the clones SSU3, SSU4 and SSU30 of UK was predicted to encode a glyoxalase/bleomycin antibiotic binding protein. Two ORFs were detected in the clone SSU28 encoding potassium ABC transporter ATPase and multidrug transporter MatE. Proteins related to adaptation to stress include different toxin-antitoxin systems and a twitching motility protein. The clones containing the ORFs encoding toxin-antitoxin system includes SSU27, MMB23, MMB38 which encoded HicA (toxin)- HicB (antitoxin), peptidase (antitoxin)-PemK (toxin) and higA (antitoxin)-higB (toxin), respectively.

Most of the proteins encoded by the ORFs on GCs showed similarity with many proteins in the database, some of which were from Treponema spp. (60 out of 66) mostly from T. denticola (24 out of 60) followed by T. putidum, T. medium, T. vincentii, T. pedis, T. phagedenis, and T. socranskii. This observation supports the previous reports that T. denticola, T vincentii and T. phagedenis carry chromosomal integrons [14, 32]. However, we have also identified 27 ORFs related to other Treponema spp.; T. putidum, T. medium, T. pedis and T. socranskii. Only six ORFs out of 66 were predicted to encode proteins related to non-treponemes including those from Paenibacillus sp., Clostridium sp. and Maripofundus sp. however, the homologies of the ORFs with these species were low (<70%) at the amino acid level.

Discussion

The PCR strategies to recover novel integron cassettes from metagenomic DNA using primers targeting the conserved sequence of IntI and attC have been successful in previous studies [15–17, 19, 33]. However, all of these metagenomic studies were carried out on non-human environmental samples. Most of the metagenomic studies involving human microbiota, were either sequence-based [34] focusing on the recovery of all genetic features or focusing on a function of interest such as antibiotic resistance [35]. No studies have been reported so far on metagenomes obtained from human saliva to detect integrons using a PCR approach. We detected mostly Treponema integrons and GCs from metagenomic DNA from human saliva from both Bangladeshi and UK samples, indicating that this methodology is applicable to any oral metagenomic sample.

This study provides an analysis of the diversity of integron GCs amplifiable in saliva metagenomic DNA. Using novel primer combinations based on the structural features of the reverse integron of T. denticola ATCC 35405 [27], we have uncovered a diverse array of gene cassettes including those in the first position, most of which are novel. Although the chromosomal integron of T. denticola ATCC 35405 is the only integron described from the oral bacteria (it has 45 gene cassettes in the array), in silico analysis of metagenomic data sets from the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) showed that two other Treponema species, including T. vincentii ATCC 35580 and T. phagedenis F0421, have also been found to carry integron GCs [14, 27, 32]. However, the PCR strategies used in this study, recovered novel GCs that were predicted to encode proteins related to those from genera other than Treponema spp.

Analyzing the proteins encoded by the GCs amplified from the oral cavity showed several interesting ORFs. GC SSU3 was predicted to encode a protein with 97% amino acid identity to the glyoxalase of Treponema pedis (WP_009105863.1, 100% coverage). It contains the Glo-EDI-BRP-like domain which can be found in metalloproteins including glyoxalase I, type I extradiol dioxygenases and bleomycin sequester proteins. Bleomycin is a glycopeptide antibiotic, which inhibits the peptidoglycan synthesis in bacteria, and also used as an antitumor drug which bind to DNA and generate free radicals that result in both double-strand and single-strand DNA breaks [36, 37]. Another ORF found on GC MMB22 detected in the Bangladeshi sample was predicted to encode streptogramin A O-acetyltransferase which had 77.0% nucleotide identity with Clostridium sp. BLN1100 and 99.0% amino acid identity with the streptogramin A O-acetyltransferase from T. denticola. Streptogramin A O-acetyltransferases mediate resistance to the streptogramin A-B combination by adding acetyl group to streptogramin, which inactivates the drugs [38].

Finally, a cof-like hydrolase gene (a member of haloacid dehalogenase superfamily) was predicted to be within a GC amplified using both GC primers and first gene cassette primers (GC SSU26 and GC TMB3). Cof-like hydrolases are a group of enzymes that inactivate halogenated aliphatic hydrocarbons by hydrolysing the carbon-halogen bonds. They are essential for detoxification of many chlorinated compounds [39, 40]. Therefore, a cof-like hydrolase in the oral cavity could play a role in detoxifying or inactivating antimicrobials or other compounds with carbon-halogen bonds that are used as antibiotics, pesticides and food preservatives such as chloramphenicol, atrazine and brominated vegetable oil, respectively.

Another function of predicted GC ORFs was related to the adaptation of bacteria to environmental stress. For example, the twitching motility PilT protein was predicted to be encoded by the ORF in GC of clone SSU5, MMB3 and MMB9. It has been shown to be involved with type IV fimbria-mediated twitching motility and protease secretion [41]. Twitching motility was also shown to play a key role in the development of biofilm from Pseudomonas aeruginosa [42]. As many oral bacteria can form biofilms on the surfaces in the human oral cavity, having a PilT-encoded GC could help them to develop biofilms and survive environmental stress.

As in previous metagenomic studies to detect integron GCs [16, 17, 43], ORFs predicted to encode proteins with regulatory functions such as toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems have been detected. Four different TA operons including the HicAB, HigBA, RelBE and MazF were detected on GCs in our study. TA cassettes are usually abundant in chromosomal integrons and are thought to have a role in the stability of the integron GC arrays [27, 44]. All of the detected TA cassettes are the members of type II toxin-antitoxin systems [45]. The toxins (HicA, HigA, RelE and MazF) work by cleaving mRNA, inhibiting translation and exhibit bacteriostatic activity, and the antitoxins (HicB, HIgB, RelE, MazE) can inhibit the action of toxin by protein-protein complex formation [46–49]. Among the four detected TA operons, only the HicAB TA system was previously found on the T. denticola integron. The nucleotide sequence of HicA and HicB system found on SSU27 cassette exhibited 97% and 99% nucleotide identity to the corresponding fourth gene cassette of the integron of T. denticola, containing HicA (TDE1838) and HicB (TDE1837) genes[27]. We have detected two HigBA TA systems in our GCs (MMU24 and MMB38), and this system has also been detected on the Vibrio cholerae super integron Several recovered GCs did not contain ORFs. This kind of ORF-less GCs was found both in the first position GC and other GC positions in the integron (clone TMB4, SSU29 and MMU2). Other noncoding cassettes have been previously found in cassette arrays comprising, for example, between 4 and 49% of Vibrio spp. cassette arrays [50]. They have been hypothesised to contain promoters or encode regulatory RNAs [2]. It was previously shown that a Xanthomonas campestris integron GC encoded trans-acting small RNA, which was capable of regulating the virulence in Xanthomonas [51].

This survey on the presence of integrons and associated GCs in salivary metagenomic DNA has resulted in new information regarding the putative functions and diversity of GCs which likely reflects the highly variable physicochemical and stressful environment of the human oral cavity.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Md. Anwar Ul Islam of University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh for helping us to collect and send the saliva sample from Bangladeshi volunteers. Md. Ajijur Rahman is supported by the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission in the UK (Ref: BDCA 2013–4). We thank Prof Pål Johnsen of UiT The Arctic University of Norway for helpful comments and suggestions on the initial version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All nucleotide sequence files are available from the NCBI database (accession number(s) KT921469 to KT921531).

Funding Statement

MAR; Commonwealth Scholarship Commission in the UK. Ref number: BDCA2013-4.

References

- 1.Cambray G, Guerout AM, Mazel D. Integrons. Annual review of genetics. 2010;44:141–66. Epub 2010/08/17. 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163504 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillings MR. Integrons: past, present, and future. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 2014;78(2):257–77. Epub 2014/05/23. 10.1128/mmbr.00056-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michael CA, Gillings MR, Holmes AJ, Hughes L, Andrew NR, Holley MP, et al. Mobile gene cassettes: a fundamental resource for bacterial evolution. The American naturalist. 2004;164(1):1–12. Epub 2004/07/22. 10.1086/421733 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerin E, Cambray G, Sanchez-Alberola N, Campoy S, Erill I, Da Re S, et al. The SOS response controls integron recombination. Science (New York, NY). 2009;324(5930):1034 Epub 2009/05/23. 10.1126/science.1172914 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collis CM, Hall RM. Gene cassettes from the insert region of integrons are excised as covalently closed circles. Molecular microbiology. 1992;6(19):2875–85. Epub 1992/10/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Partridge SR, Recchia GD, Scaramuzzi C, Collis CM, Stokes HW, Hall RM. Definition of the attI1 site of class 1 integrons. Microbiology (Reading, England). 2000;146 (Pt 11):2855–64. Epub 2000/11/07. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collis CM, Recchia GD, Kim M-J, Stokes HW, Hall RM. Efficiency of Recombination Reactions Catalyzed by Class 1 Integron Integrase IntI1. Journal of bacteriology. 2001;183(8):2535–42. 10.1128/JB.183.8.2535-2542.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stokes HW, O'Gorman DB, Recchia GD, Parsekhian M, Hall RM. Structure and function of 59-base element recombination sites associated with mobile gene cassettes. Molecular microbiology. 1997;26(4):731–45. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6091980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escudero JA, Loot C, Nivina A, Mazel D. The Integron: Adaptation On Demand. Microbiology spectrum. 2015;3(2). 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0019-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collis CM, Hall RM. Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1995;39(1):155–62. Epub 1995/01/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall RM, Collis CM. Antibiotic resistance in gram-negative bacteria: the role of gene cassettes and integrons. Drug resistance updates: reviews and commentaries in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy. 1998;1(2):109–19. Epub 2006/08/15. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stokes HW, Hall RM. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons. Molecular microbiology. 1989;3(12):1669–83. Epub 1989/12/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partridge SR, Tsafnat G, Coiera E, Iredell JR. Gene cassettes and cassette arrays in mobile resistance integrons. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2009;33(4):757–84. Epub 2009/05/07. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00175.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu YW, Rho M, Doak TG, Ye Y. Oral spirochetes implicated in dental diseases are widespread in normal human subjects and carry extremely diverse integron gene cassettes. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2012;78(15):5288–96. Epub 2012/05/29. 10.1128/aem.00564-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes AJ, Gillings MR, Nield BS, Mabbutt BC, Nevalainen KM, Stokes HW. The gene cassette metagenome is a basic resource for bacterial genome evolution. Environmental microbiology. 2003;5(5):383–94. Epub 2003/04/26. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsaied H, Stokes HW, Kitamura K, Kurusu Y, Kamagata Y, Maruyama A. Marine integrons containing novel integrase genes, attachment sites, attI, and associated gene cassettes in polluted sediments from Suez and Tokyo Bays. The ISME journal. 2011;5(7):1162–77. Epub 2011/01/21. 10.1038/ismej.2010.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsaied H, Stokes HW, Nakamura T, Kitamura K, Fuse H, Maruyama A. Novel and diverse integron integrase genes and integron-like gene cassettes are prevalent in deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Environmental microbiology. 2007;9(9):2298–312. Epub 2007/08/10. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01344.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amann RI, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiological reviews. 1995;59(1):143–69. Epub 1995/03/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stokes HW, Holmes AJ, Nield BS, Holley MP, Nevalainen KM, Mabbutt BC, et al. Gene cassette PCR: sequence-independent recovery of entire genes from environmental DNA. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2001;67(11):5240–6. Epub 2001/10/27. 10.1128/aem.67.11.5240-5246.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenig JE, Sharp C, Dlutek M, Curtis B, Joss M, Boucher Y, et al. Integron Gene Cassettes and Degradation of Compounds Associated with Industrial Waste: The Case of the Sydney Tar Ponds. PloS one. 2009;4(4):e5276 10.1371/journal.pone.0005276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005;43(11):5721–32. 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, Paster BJ, Tanner AC, Yu WH, et al. The human oral microbiome. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192(19):5002–17. Epub 2010/07/27. 10.1128/jb.00542-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diaz-Torres ML, Villedieu A, Hunt N, McNab R, Spratt DA, Allan E, et al. Determining the antibiotic resistance potential of the indigenous oral microbiota of humans using a metagenomic approach. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258(2):257–62. Epub 2006/04/28. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00221.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seville LA, Patterson AJ, Scott KP, Mullany P, Quail MA, Parkhill J, et al. Distribution of tetracycline and erythromycin resistance genes among human oral and fecal metagenomic DNA. Microbial drug resistance (Larchmont, NY). 2009;15(3):159–66. Epub 2009/09/05. 10.1089/mdr.2009.0916 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts AP, Mullany P. Oral biofilms: a reservoir of transferable, bacterial, antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8(12):1441–50. 10.1586/eri.10.106 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie G, Chain PS, Lo CC, Liu KL, Gans J, Merritt J, et al. Community and gene composition of a human dental plaque microbiota obtained by metagenomic sequencing. Molecular oral microbiology. 2010;25(6):391–405. Epub 2010/11/03. 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00587.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman N, Tetu S, Wilson N, Holmes A. An unusual integron in Treponema denticola. Microbiology (Reading, England). 2004;150(Pt 11):3524–6. Epub 2004/11/06. 10.1099/mic.0.27569-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang X. A contig assembly program based on sensitive detection of fragment overlaps. Genomics. 1992;14(1):18–25. Epub 1992/09/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology. 1990;215(3):403–10. Epub 1990/10/05. 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80360-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazel D. Integrons: agents of bacterial evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(8):608–20. Epub 2006/07/18. 10.1038/nrmicro1462 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stokes HW, O'Gorman DB, Recchia GD, Parsekhian M, Hall RM. Structure and function of 59-base element recombination sites associated with mobile gene cassettes. Molecular microbiology. 1997;26(4):731–45. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Y-W, Doak TG, Ye Y. The gain and loss of chromosomal integron systems in the Treponema species. BMC evolutionary biology. 2013;13(1):1–9. 10.1186/1471-2148-13-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nield BS, Holmes AJ, Gillings MR, Recchia GD, Mabbutt BC, Nevalainen KM, et al. Recovery of new integron classes from environmental DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;195(1):59–65. Epub 2001/02/13. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59–65. 10.1038/nature08821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sommer MO, Dantas G, Church GM. Functional characterization of the antibiotic resistance reservoir in the human microflora. Science. 2009;325(5944):1128–31. 10.1126/science.1176950 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, Stubbe J. Bleomycins: towards better therapeutics. Nature reviews Cancer. 2005;5(2):102–12. Epub 2005/02/03. 10.1038/nrc1547 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahne D, Leimkuhler C, Lu W, Walsh C. Glycopeptide and lipoglycopeptide antibiotics. Chemical reviews. 2005;105(2):425–48. Epub 2005/02/11. 10.1021/cr030103a . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Meester C, Rondelet J. Microbial acetylation of M factor of virginiamycin. The Journal of antibiotics. 1976;29(12):1297–305. Epub 1976/12/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koonin EV, Tatusov RL. Computer analysis of bacterial haloacid dehalogenases defines a large superfamily of hydrolases with diverse specificity. Application of an iterative approach to database search. J Mol Biol. 1994;244(1):125–32. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1711 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardman DJ. Biotransformation of halogenated compounds. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1991;11(1):1–40. 10.3109/07388559109069182 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han X, Kennan RM, Davies JK, Reddacliff LA, Dhungyel OP, Whittington RJ, et al. Twitching motility is essential for virulence in Dichelobacter nodosus. Journal of bacteriology. 2008;190(9):3323–35. Epub 2008/03/04. 10.1128/jb.01807-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiang P, Burrows LL. Biofilm formation by hyperpiliated mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185(7):2374–8. Epub 2003/03/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koenig JE, Boucher Y, Charlebois RL, Nesbo C, Zhaxybayeva O, Bapteste E, et al. Integron-associated gene cassettes in Halifax Harbour: assessment of a mobile gene pool in marine sediments. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10(4):1024–38. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01524.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szekeres S, Dauti M, Wilde C, Mazel D, Rowe-Magnus DA. Chromosomal toxin–antitoxin loci can diminish large-scale genome reductions in the absence of selection. Molecular microbiology. 2007;63(6):1588–605. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leplae R, Geeraerts D, Hallez R, Guglielmini J, Dreze P, Van Melderen L. Diversity of bacterial type II toxin-antitoxin systems: a comprehensive search and functional analysis of novel families. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(13):5513–25. Epub 2011/03/23. 10.1093/nar/gkr131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makarova KS, Grishin NV, Koonin EV. The HicAB cassette, a putative novel, RNA-targeting toxin-antitoxin system in archaea and bacteria. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(21):2581–4. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl418 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jorgensen MG, Pandey DP, Jaskolska M, Gerdes K. HicA of Escherichia coli defines a novel family of translation-independent mRNA interferases in bacteria and archaea. Journal of bacteriology. 2009;191(4):1191–9. Epub 2008/12/09. 10.1128/jb.01013-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33(3):966–76. Epub 2005/02/19. 10.1093/nar/gki201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Gerdes K. Two higBA loci in the Vibrio cholerae superintegron encode mRNA cleaving enzymes and can stabilize plasmids. Molecular microbiology. 2006;62(2):397–411. Epub 2006/10/06. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05385.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boucher Y, Nesbo CL, Joss MJ, Robinson A, Mabbutt BC, Gillings MR, et al. Recovery and evolutionary analysis of complete integron gene cassette arrays from Vibrio. BMC evolutionary biology. 2006;6:3 Epub 2006/01/19. 10.1186/1471-2148-6-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen X-L, Tang D-J, Jiang R-P, He Y-Q, Jiang B-L, Lu G-T, et al. sRNA-Xcc1, an integron-encoded transposon- and plasmid-transferred trans-acting sRNA, is under the positive control of the key virulence regulators HrpG and HrpX of Xanthomonas campestris pathovar campestris. RNA Biology. 2011;8(6):947–53. 10.4161/rna.8.6.16690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All nucleotide sequence files are available from the NCBI database (accession number(s) KT921469 to KT921531).