Abstract

Using qualitative data collected from adolescent Latinas and their parents, this article describes ways in which family relationships are organized within low-income Latino families (n = 24) with and without a daughter who attempted suicide. Based on a family-level analysis approach, we present a framework that categorizes relationships as reciprocal, asymmetrical, or detached. Clear differences are identified: Families of non-attempters primarily cluster in reciprocal families, whereas families with an adolescent suicide attempter exhibit characteristics of asymmetrical or detached families. Our results highlight the need for detailed clinical attention to family communication patterns, especially in Latino families. Clinicians may reduce the likelihood of an attempt or repeated attempts by raising mutual, reciprocal exchanges of words and support between parents and daughter.

The research presented in this article is motivated by the significant, sobering fact that Latina adolescents attempt suicide more often than any other teenagers in the United States regardless of ethnicity and gender (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008; Rew, Thomas, Horner, Resnick, & Beuhring, 2001; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003). Over the years, researchers have discerned that among Latina teens, family conflicts often trigger suicidal behavior (Berne, 1983; Garcia, Skay, Sieving, Naughton, & Bearinger, 2008; Herrera, Dahlblom, Dalgren, & Kullgren, 2006; Razin et al., 1991; Zayas, Gulbas, Fedoravicius, & Cabassa, 2010). Generally, research that suggests a link between family discord and Latina teen suicidality has been based on data drawn from interviews with either the attempting girl or the parent. As a result, our ability to identify ways in which family dynamics influence suicidal behavior is constrained, raising the question of whether suicidality is associated with particular family dynamics. Using qualitative data collected with multiple family members, this article describes the different ways in which family relationships are organized within low-income Latino families living in New York City. We present a framework for understanding how differences in family relationships influence suicidal behavior, providing an important first step in identifying and carrying out interventions that enhance positive outcomes for suicide attempters and their families.

A review of the literature illustrates that the clinical and theoretical frameworks of many studies posit a link between family relationships and Latina suicide attempts. In his now classic study of suicide attempts among young Puerto Rican women in New York City, Trautman (1961) reported that severe tension between the attempter and her spouse or her mother frequently precipitated the attempt. Subsequent research continues to demonstrate that stressed relations between attempters and their parents seem to be a common factor (Brent et al., 1988; Marttunen, Aro, & Lonnqvist, 1993; Moscicki, 1999; Wagner, 1997). Relations between the attempter and her parent(s) are typically characterized as tense or weak, stemming from poor communication, mentoring, or support (Garcia et al., 2008; Herrera et al., 2006; Razin et al., 1991; Zayas, Bright, Alvarez-Sanchez, & Cabassa, 2009; Zayas et al., 2010).

This research has guided our conceptualization that Latina teen suicidal behavior is shaped by the interpersonal dynamics of the family. Yet the primacy of data collection with either attempters or their parents (rarely both) presents a limitation of this extant scholarship. Multiple perspectives from parents and adolescents enrich understanding of the interaction in the family system. Our aim, then, is to extend this body of literature by contextualizing how family functioning influences suicide attempts through family-level analysis. We utilize family case summary analysis to illustrate how families react to and deal with stress and change, and to contextualize how suicidal behavior is shaped by family dynamics. By comparing families with an adolescent suicide attempter to families without an attempter, we identify how differences in family relationships influence individual outcomes.

Method

The data presented in this article are drawn from a larger mixed method project that explored suicide attempts among adolescent Latinas in low-income families in New York City. Participants in the qualitative portion of the larger study included 122 Latinas between the ages of 11 and 19 who had attempted suicide within six months before the interview, as well as their mothers (n = 86) and fathers (n = 19), and 110 Latinas with no lifetime history of suicide attempts and their mothers (n = 83) and fathers (n = 17). Adolescents who had attempted suicide were recruited from mental health services associated with a large Latino-serving agency, a private psychiatric hospital, and a municipal hospital with psychiatric emergency and outpatient departments. Adolescents with no lifetime history of suicide were recruited from local community agencies (e.g., after-school, prevention, and youth development programs) and primary care medical clinics.

In this article, we focus on a subsample of interviews with 12 families with an adolescent suicide attempter and 12 families with an adolescent with no reported history of suicide behavior (see Table 1). Interviews were selected by the research team after careful readings of each interview transcript and notes taken during interviews. Interviews were chosen for inclusion in the subsample because the narratives provided by adolescents and parents from each family were particularly descriptive and rich in detail. The practice of selecting interviews based on their depth and richness is common in qualitative research, as the effectiveness of qualitative research is derived not from large sample sizes or randomness, but from the collection of detailed narratives by research participants who provide reflection on and critical discussion of their personal experiences (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2008).

Table 1. Characteristics of study sample of adolescent Latina girls, their mothers and fathers (N=52).

| Adolescent girls (N=24) | Mothers (N=24) | Fathers (N=4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M(SD) | n (%) | M(SD) | n (%) | M(SD) | n (%) | |

| Age | 15.5 (1.8) | 40.8 (6.8) | 40.1 (3.8) | |||

| Education | 8.75 (1.8) | 11.5 (2.5) | 11.0 (4.6) | |||

| US Born | 19 (79.2) | 6 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | |||

| Hispanic Cultural Group | ||||||

| Dominican | 9 (37.5) | 9 (37.5) | 2 (50.0) | |||

| Puerto Rican | 5 (20.8) | 6 (25.0) | - | |||

| Mexican | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (50.0) | |||

| Colombian | 3 (12.5) | 3 (12.5) | - | |||

| Other | 3 (12.5) | 3 (12.5) | - | |||

The average age of the girls in the subsample was 15.5 years (SD = 1.8). Mothers had a mean age of 40.8 years (SD = 6.8) and fathers' age on average was 40.1 years (SD = 3.8). The majority of the adolescents were born in the United States (79%), whereas 25% of mothers and fathers reported to be U.S.-born. Participants identified with seven Hispanic subgroups, including Dominican, Puerto Rican, Mexican, Colombian, Ecuadoran, El Salvadoran, and Nicaraguan, and were representative of the total sample. It should be noted that within this subsample, fathers' perspectives are underrepresented. This reflects the fact that the majority of adolescents in the total sample did not live with or have regular contact with their biological fathers.

Qualitative Interview

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with all participants in either English or Spanish, depending on the participant's preference, and audiotaped and transcribed. Spanish interviews were not translated, as all members of the research team are bilingual. Interviewers were master's- or doctoral-level social workers or psychologists, trained to encourage the participants to speak freely, spontaneously, and in detail about the topic areas included in the interview, thus allowing for as much information to emerge as possible. Carefully designed interview guides were employed to maximize the validity and reliability of the data obtained through interviews. The following topics were explored with each participant: relationships with other family members, including extended kin; roles, responsibilities, rules, and discipline; conflict and conflict resolution; life outside the family home, including peer networks, dating, school activities, and future plans; and a retrospective, detailed account of the suicide attempt, if applicable.

Qualitative Data Analysis

To develop family-level analysis of the dataset, we based our procedures on those outlined by Knafl and colleagues (Ayres, Kavanaugh, & Knafl, 2003; Knafl & Ayres, 1996; Knafl & Deatrick, 2006) to reconfigure individual interview transcripts into family case summaries. This entailed four major stages: (a) coding of individual interviews to identify important themes for use in the development of family case summary guidelines, (b) development of guidelines and writing of family case summaries based on the guidelines, (c) identification of themes in family case summaries, and (d) construction of a conceptual cluster matrix (Miles & Huberman, 1994) to develop a typology of family relationships.

In order to develop guidelines to construct family case summaries, it was first necessary to read, code, and identify themes within individual interviews. This allowed guidelines to be based in the data rather than researcher interests, and, as a result, guidelines incorporated the research participants' definitions, experiences, and thoughts about their relationships with other family members. This process of coding, which stemmed from techniques described by Barkin, Ryan, and Gelberg (1999), proceeded as follows. Using NVivo® 7, two members of the research team applied four broad codes (mutuality, familism, autonomy, and parental expectations) to individual transcripts. These codes were consistent with the sociocultural conceptual foundation of the study (Zayas, Lester, Cabassa, & Fortuna, 2005). Coded text was segmented according to meaning units, so that a coded statement contained one idea and could be understood after the text was extracted from its original content (Tesch, 1990). Percent agreement was calculated using the coding comparison module in NVivo®, and a threshold of 75% agreement was established. This level of agreement is widely used in qualitative studies (see Miles & Huberman, 1994). A team meeting was held to discuss sections of text that fell below the threshold, and text was recoded based on consensus. Approximately 20% of coded text fell below the threshold and was recoded.

To identify subthemes, four coders carried out pile-sorting tasks on text segments coded within each broad code (Barkin et al., 1999). After each pile sort, the coders described in their own words how they constructed the piles. This limited the likelihood that subthemes were based solely on researcher interests (Barkin et al.). Results from the pile-sorts were entered into ANTHRO PAC® 4.0 (Borgatti, 1996) for analysis. Using the nonmetric, multidimensional scaling module within the program, a data display was exported that revealed which text segments were sorted similarly across all four coders. Based on these similarities, a team meeting was held with the coders to identify subthemes. These subthemes formed the basis of the guidelines for writing family case summaries.

The guidelines were organized in the following manner: (a) description of household and family, including level of interaction among family members and how family members talk about who “counts” as family; (b) definition, management, and distribution of household and family responsibilities, rules, and discipline; (c) presence and demonstration (or lack) of support, understanding, affection, and communication among family members in everyday life and times of crisis or conflict; and (d) descriptions of how family members experience and cope with conflict and/or change. As family case summaries were written, the guidelines encouraged consistent preparation by “reminding” team members to focus on key topics.

Research team members were then charged with synthesizing information for several family units. A family case summary was composed, using the guidelines as a key, by integrating data from transcripts into a single narrative account. To inform the process of writing a family case summary, ethnographic techniques were utilized, including presentation of dialogue and analytic remarks (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 1995). Dialogue, especially exchanges that occurred between family members, was reproduced as accurately as possible through direct and indirect quotes and paraphrasing. Dialogue was cited according to line numbers in original transcripts, thus retaining a close link with the original data. In capturing dialogue, we were able to develop a detailed account of salient interactions (as defined by participants) at the group level, shedding light on how family members who experienced the same event nevertheless interpreted it differently. Analytic remarks were used to discourage reliance on conclusive statements when interpreting the data, and instead, promoted a way of thinking about the data that favored alternative explanations. Throughout the process of writing, team members met biweekly to review family case summaries and discuss analytic remarks.

Once prepared, family case summaries were treated as primary units of analysis (Ayres et al., 2003). Family case summaries were reviewed and compared to identify the various ways in which family relationships were organized across families in the sample. Four essential themes emerged as salient to our understanding of how family relationships seemed to be organized: (a) commitment, (b) respect, (c) awareness, and (d) authority. We defined commitment as the way in which individual family members actively demonstrate their membership in that family. In other words, individuals show (or do not show) other family members that they are active participants in the family by carrying out their respective roles, duties, and responsibilities. Respect was defined as the ways in which family members communicate, acknowledge, and/or accept another person's decisions. It is an acknowledgment that a family member is engaged in a relationship with other persons. We defined awareness as the ways in which family members show one another that they acknowledge, understand, and can anticipate another family member's needs and wants. The final theme, authority, referred to the ways in which governance is distributed within a family, including the delineation of rules, consequences to breaking rules, and different ways in which family members interpret authority.

To analyze how each of these themes manifested within and across attempter and non-attempter families, we generated a conceptual cluster matrix (Miles & Huberman, 1994; also see Knafl & Ayres, 1996, for a detailed discussion of the use of matrices within qualitative research). Using Microsoft Excel®, the matrix was organized by family unit (rows) and themes (columns). Data in the cells incorporated information about who in the family expressed the theme, as well as the degree of consensus among family members regarding that expression. The matrix displayed the broader ways in which family members engaged one another in terms of commitment, respect, awareness, and authority; and we used the matrix to document differences in those relationships.

Results

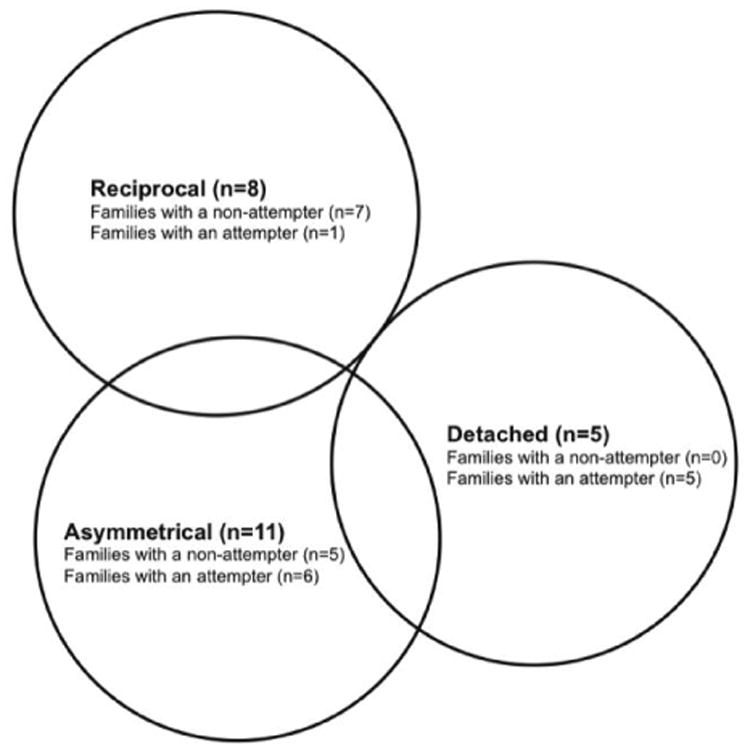

We were able to discern patterns of how family relationships were organized, identifying three configurations in the ways that commitment, respect, awareness, and authority emerged within families: (a) reciprocal, (b) asymmetrical, and (c) detached. Not all families fell discretely into a single type, but relationships within a family could be characterized as predominantly reciprocal, asymmetrical, or detached. We present in Figure 1 the numbers corresponding to the classification of the 24 families in our subsample. We were able to identify clear differences between families with an adolescent suicide attempter and families with an adolescent with no reported history of suicide attempts. Families of non-attempters primarily clustered as reciprocal, whereas families with an adolescent suicide attempter exhibited asymmetrical or detached characteristics. The clustering was not absolute, but an in-depth look into these negative cases, discussed below, sheds more light on the influence of family dynamics on adolescent suicidal behavior. Quotes from the interviews are presented in English. For those quotes that were translated, we present the original Spanish versions in endnotes.

Figure 1. Distribution of family relationship types within study sample.

Reciprocal Relationships

In families that we classify as reciprocal, the majority of family units had adolescents who had never engaged in suicidal behavior (n = 7). Only 1 family with an attempter was characterized as reciprocal, discussed in more detail below. Reciprocal families are identifiable by a distinct pattern of communication and support that differs from the other categories. Specifically, we find that family members interact with one another in reciprocal ways: they engage in practices in which each individual contributes to the overall functioning of the family. For example, a mother of a non-attempter described the commitment, dedication, and sacrifice in raising a family, where every family member was “trying to do the best for us” as a family.1 This family's reciprocity is clearly expressed in the words they used to describe their interactions: mother and daughter frequently used first-person plural. This is especially pronounced in the mother's interview, which is sprinkled with words such as “ibamos” (we went), “veiamos” (we saw), and “pensamos” (we think).

The sentiment of togetherness is expressed frequently among members in reciprocal families. As a non-attempter explained, even external stressors, such as finances, represent an opportunity for the family to come together: “It's like money-wise, [you] know? It's hard, like food… My mom tries her best to feed us, and she gives us the right amount of love, and she's like a perfect mom. Like we don't have money, but when we're with her, it's like we don't need it.” The daughter reciprocated the actions of commitment by helping her mother with household duties, including cooking, cleaning, and grocery shopping. This reciprocal network of support helped this family function during economic hardship.

It is notable that reciprocity extends to the issue of respect, as well. Respect, or respeto, is an important value within Latino cultures. It is often translated as a value that acknowledges hierarchy and authority: individuals with more authority are treated with respect (Calzada, Fernandez, & Cortes, 2010). Within Latino families, then, one would expect that respeto maps clearly upon relationships between children and their parents: Children should be expected to respect their parents as authority figures. Yet in reciprocal families, we find that respeto flows both ways. As a non-attempter noted, “The reason why I respect her is ‘cause she respects me.” This has a significant impact on the ways in which daughters interact with their parents. By showing respect, parents provide an opportunity for their daughter to learn and grow from her mistakes. In a non-attempter family, for example, the daughter started dating a boy of whom her mother and father disapproved. Yet, they respected the girl's decision because “one day, she will realize why he is not suitable for her.”2 Both parents frequently invited the boy over to their house, where they could monitor the couple, and they provided a pleasant home environment for them. Over time, the daughter broke off the relationship. The daughter appreciated that her parents wanted to get to know her boyfriend. She commented that “my family, they've always been like that, based on like values and beliefs, and we have to respect each other.”

In our subsample of Latino families, only one family with an adolescent suicide attempter was classified as reciprocal. In this family, the relationship between the mother and daughter was close. The family also had an extended kin network of aunts and uncles, and the weekends were spent together as a family. Mother and daughter spent frequent evenings together, cooking and talking about the day's activities. Often, mother and daughter slept in the same bed. One night, the daughter told her mother that she “felt life was pointless. It has no meaning.” Recognizing this troubling change in her daughter's attitude, the mother recalled that “I couldn't sleep [that night]. I held onto my little girl, and I waited until the morning. I got her up for school, and everything. When she was going to leave and told me, ‘I'm going,’ I told her, ‘No, you are not going to school. You are coming with me to the pediatrician.”3 The mother explained that she knew something was wrong with her daughter. The pediatrician referred her to a psychologist, and an appointment was set for 2 months later. One month before this date, the daughter attempted suicide by taking a cocktail of pill, “some Tylenol, Motrin, my Claritin, and some red pills in the kitchen… I guess [I thought] the world keeps on going, and I go underground six feet.” This case reflects the fact that suicidal behavior is influenced not only by familial factors, but also by individual psychology. In this case, an otherwise reciprocal family fell victim to an endogenous depression and lack of timely access to mental health care.

Asymmetrical Relationships

The majority of families within our subsample were classified as asymmetrical (n = 11), including 5 non-attempter families and 6 attempter families. Like reciprocal families, asymmetrical families manifest themes of commitment, respect, awareness, and authority. Asymmetrical families are distinct by the unidirectional nature of the relationship and corresponding interactions. Asymmetrical families are usually characterized by a single family member giving completely to relationships with family members without reciprocation from those individuals. Demonstrations of commitment, respect, and awareness are often rejected by other family members. For example, a non-attempter expressed her frustration in getting her mother to understand her experience of being a teenager and her burgeoning desire for independence. The daughter had repeatedly asked her mother if she could spend an afternoon with her friends, but her mother was unyielding. As her mother explained, “I am very jealous in this sense. If she leaves [the house], she leaves with me. If not, she does not leave with anyone.”4 The daughter tried to express her feelings to her mother, but her mother would not listen: “I'm like, ‘Mom, if I respect what you're telling me, I obey what you're telling me, why can't you have the same respect to me? Why can't you help me out in that kind of way too? I'm going along with what you're telling me. Why can't you go along with what I'm telling you?’ So to me, the word respect for me is like respecting the fact that you have your own opinions and I have my own opinions. And that you believe that and I don't believe that. And I'm expecting you to respect what I believe and I'm respecting what you believe.”

It is most often within this type of asymmetry that we see narratives of conflict between a daughter's perceived need for autonomy and her parent's wishes for her to remain in a position of dependence. This is not to say that these conflicts do not exist in other family types, such as reciprocal families, but rather the asymmetry in social interactions inhibits family members' abilities to come together and reach an understanding about one another's needs. Girls described feeling frustrated when trying to talk to their parents. They tried to discuss their feelings with their parents, but felt that parents rarely acknowledge those feelings. As a non-attempter noted, her parents were “always pushing [her] opinions away.” As a result, we found daughters engaging in practices of rebellion, such as skipping school, breaking household curfews, and dating secretly, in response to their interactions with their parents.

In some cases, the asymmetry is typified by parental dependence on the daughter. A non-attempter explained that her desire to go to college was superseded by the need to care for her single mother, whose physical ailments, debilitating depression, language barriers, and inability to work inhibited her mother from fulfilling what the daughter interpreted as her mother's responsibilities to the family. In this relationship, the daughter had become the authority figure, setting her own rules and responsibilities. This role reversal was a source of conflict for a number of girls who found themselves in similar situations. Latina adolescents frequently questioned their established roles within the family: were they daughters, providers, or friends? As a non-attempter described, “I feel like I have like a double personality.”

Asymmetry is not only a characteristic distributed across families with adolescents who have never attempted suicide, but it is also found in families with a Latina teen suicide attempter. One mother of an attempter expressed her anguish in trying to understand her daughter's behavior. The mother explained that her daughter had “[gone] through things that she's not ready for,” including being sexually assaulted by her uncle at age 10. The mother tried to press charges, but her daughter asked her to stop, and the mother gave in to her daughter's wishes. The mother described her daughter as aggressive, and she had visited her daughter's school to talk with the school counselors and principal about how to help her. The girl stated that she wanted to be left alone to deal with her problems and felt that her mother “really just doesn't know how to let things go.” Within this context, in which the mother was trying to break through the barriers her daughter had built around herself, the daughter attempted suicide. The daughter described the moment in clear detail. She said, “I thought about, like, everything that…was stressful to me. Or anything that anybody else has done to me, and how much I disliked myself, and how much I didn't care about certain people that I should care about… I was feeling really down. I usually feel down. And I didn't know [what] about… I thought of feelings like suicide.”

Given that both non-attempters and attempters live in asymmetrical families, we must ask ourselves what features distinguish these two groups of adolescents. Our analysis of the data and experience gained in this project suggest several possible causes. First, non-attempters are able to locate other mechanisms for support within the family system, such as extended kin, and outside of the family through school-based activities or church, for example. Second, non-attempters seem more likely to express an empathetic attitude toward a family member's inability to engage in a reciprocal relationship. A non-attempter explained that her father's failure to mentor her was due to his own upbringing. She explained that “he is a good father, he's just…they didn't show him how to raise us well.” Finally, there is clear expression of hope and resilience in the narratives of adolescents who have never attempted suicide. As another non-attempter described when dealing with interpersonal conflict, “[Either] you do something about it, like try to fix something, or just let it go. ‘Cause you know, [if] I can't do anything about it, I should be happy with the way that I am.”

Detached Relationships

Detached families exhibit a clear lack of commitment, respect, and awareness by all family members in the relationship, and authority is either demonstrated through physical abuse, or it is not enforced. In these families, if we imagine a family as a web of interaction, then the threads that link family members together—the relationships— are broken. Not surprisingly, all families in our subsample that were classified as detached were families with a suicide attempter (n = 5). It should be noted that detachment often results from a turning point that causes webs of interaction to break. Sometimes, reunification served as the breaking point. For example, an attempter described being “left” in Ecuador when her parents immigrated to the United States. She was 3 years old and was under her aunt and uncle's care, but she was physically abused and neglected. Upon reuniting with her parents in the United States at age 10, she encountered a family that did not interact together. As the daughter explained, “We do not help each other in my house. It should be. It should be that we tell each other about our problems and try to help each other move forward together…but in my house, each person lives for his or her own life.”5

In another family, what interaction there was between mother and daughter was often exhibited through violence. The mother stated that she did not know how to handle what she described as her daughter's aggressiveness. She said that her daughter was frequently involved in physical altercations with her siblings and peers at school. Desperate to control her daughter's unwieldy behavior, the mother acknowledged that she felt her only recourse to discipline her child was through violence: “What I want to do is grab her and explode in anger…. If I have to grab her and let her have it, I let her have it. I grab her, and if I have to strangle her, I strangle her. I am asking God to help me calm down and not…grab her and kill her. I tell her… trying to do the best for us” as a family that “I gave you life and I can take it away.”6

Heated, and often physical, arguments with her mother left the young teen attempter feeling like she did not “have anybody to speak to that would understand me.” Although she lived in an apartment bustling with people, including her mother, four siblings, aunt, and two cousins, the daughter was overcome by feelings of loneliness. Her feelings of alienation within her family were especially acute when she suffered a miscarriage. She felt that nobody cared about her during this difficult time. She felt that her mother “was like, ‘since there's no baby, I don't have to, like, be there for you as much.’”

Within these families, detachment becomes a metaphor by which we can understand adolescents' subjective realities. As each day passes, the absence of supportive relationships and, for many, experiences of physical or verbal abuse overwhelm these girls. They describe their worlds in terms of “collapsing,” or causing a sensation of “suffocating” or “drowning.” Often, these adolescents interpret their own actions as the cause of family detachment, which leads to intense feelings of guilt. As one attempter stated, “Like, just everything, I felt like it was just collapsing…I was like, ‘I just can't do this because I just feel guilty all the time, and they don't get it.’ I felt like nobody understood how I felt, and they wouldn't help me. So I just decided to take the pills.”

Parents within these families often reacted with disbelief or anger when they learned their daughters had tried to take their lives. Often, parents described suicidal behavior as a “way to get attention.” Others interpreted it as a way to inflict hurt upon the family. For example, a mother stated that her daughter engaged in suicidal behavior to cause more problems for the family. She recounted a conversation with her daughter in the hospital, during which she told her, “In what way do you think this is helping us? I feel like I am putting in my part, but you are not. You are making everything worse.”7 Detached families seem to lack the affective tie that is more evident in reciprocal families.

Conclusion

This study builds on past research on Latino family functioning, childrearing, and parent-child interaction by contextualizing cultural variations in family dynamics. While the predominant model of the Latino family emphasizes the importance of authoritarian, and often restrictive, parenting (Blair, Blair, & Madamba, 1999; Cardona, Nicholson, & Fox, 2000; Finkelstein, Donenberg, & Martinovich, 2001), attention to suicidal Latinas and their families has been absent from this clinical and empirical literature (see Zayas, Lester, Cabassa, & Fortuna, 2005, for a review). The unique aspects of this report are the inclusion of both adolescent and parent perspectives, as well as the use of a novel and very promising methodology for family-level analyses.

Using family case summary analysis with in-depth interviews conducted with suicidal and non-suicidal young Latinas and their parents, we demonstrate considerable differences in parent–adolescent relationships. These findings support the development of a framework for family types among girls who have attempted suicide, or who have no such history, based on the themes of commitment, respect, awareness, and authority. We see that within Latino families—some who had experienced a suicide attempt by an adolescent daughter and some who had not—there are clear differences in the ways each of these themes are negotiated and distributed among family members and across families within our sample. Often, the navigation of these issues can be a source of tension within families and strongly impact the decision-making processes of Latina adolescents, including decisions to engage in suicidal behavior. In reciprocal families, we see that the ways in which commitment, respect, awareness, and authority are engaged help offset the numerous challenges families face, such as financial stress.

In other family types, including asymmetrical and detached families, the configuration of these themes can lead to less-than-optimal dynamics. Although both non-attempters and attempters live in asymmetrical families, our interpretation of the data is that the absence of alternative mechanisms for support and lack of hope seem to influence a Latina adolescent's decision to attempt suicide. More research is needed in this area to identify factors that protect some adolescents in asymmetrical families from engaging in suicidal behavior. In the detached families in our sample, every family had an adolescent who had attempted suicide. In detached families, parents often construe the young person's attempt as inappropriate or dramatic. This suggests that these family types lack the structures needed to support recovery, and may instead encourage future attempts.

Ultimately, the identification of reciprocal, asymmetrical, and detached as separate types of family relationships represents a framework for assessing family influence on youth suicidal behavior. We acknowledge several limitations that restrict the generalizability of our findings. For example, our results are based on data collected with low-income families only, and we did not confirm the classification of families as reciprocal, asymmetrical, and detached with our research participants. Future confirmatory research and analyses are needed. Another limitation is that we selected qualitative interviews from participants based on the richness of their narratives, and it must be noted that families who demonstrated in-depth communication may have differed in crucial ways from those families who did not speak in great detail during the interview. The majority of families within our sample were structured as single-headed households, which tells us about the dynamics and stresses in such homes. Increased attention to two-parent families would provide much-needed information about the role that Hispanic fathers play in their daughters' development and in their influence on the girls' tendencies to attempt suicide. For example, an increasing number of studies indicate that the presence of a nurturing father may act as a protective factor against adolescent girls' participation in high-risk behavior (Ellis et al., 2003; Formoso, Gonzales, & Aike, 2000; McLanahan, 1999). It is important to incorporate perspectives from Latino families to include those with different household structures, from the middle- to upper-social levels, and to involve additional family members, such as siblings of the adolescents in question. Such an empirically-grounded approach will enable us to articulate more clearly the ways in which the link between individual family members and the family unit as a whole influence individual outcomes and suicidal behavior.

Implications for Practice

Clinicians practicing in communities and organizations with large numbers of Hispanic families will likely encounter those whose daughters have attempted suicide. Moving beyond an understanding of family systems and the application of clinical interventions, providers can also consider the types of Latino families that are associated with suicidal Latina adolescents and the manner in which their families interact. Our project and past research (e.g., Moscicki, 1999; Wagner, 1997) indicate that family tensions often set the conditions for suicidal behavior among young Latinas. Stress occurs primarily in the adolescent's relationship with her parents, although occasionally, sibling relationships play a salient role (see Zayas et al., 2010).

We recommend that clinicians use the family typology we derived to address the communication patterns in families of attempters. For families of suicide attempters, clinicians may reduce the likelihood of an attempt or repeated attempts by raising the mutual, reciprocal exchanges of words, affections, understanding, and support between parent(s) and daughter. For example, our results indicate that interdependent communication is an element that promotes positive family dynamics. Respeto, in particular, emerges as a salient cultural value that encourages interpersonal and harmonious interactions between parents and their children. Based on the results of our research, interventions that foster interdependent decision making would be culturally sensitive and more appropriate than interventions that promote individual autonomous decision making, which is countercultural to Latino values (Dumka, Lopez, & Carter, 2000). Indeed, past analyses indicate that as parent–child mutuality increases, the likelihood of a suicide attempt drops by over 50% (Zayas et al., 2009).

Another possible dimension to target during therapy is parent–child negotiation of realistic expectations. Our research indicates that unrealistic expectations, particularly surrounding issues of dating, sexuality, and family responsibilities, lead to recurrent episodes of conflict. We envision an integrated program that would supplement individually targeted therapy with the at-risk adolescent with activities that foster positive communication dynamics within the family, such as the Familias Unidas intervention (see Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002). At the core of most suicide attempts are problematic communications in families. Interventions that enhance understanding and mutuality can be a very effective tool for clinicians.

Implications for Practice.

Family tension often sets the conditions for suicidal behavior among young Latinas. Interventions that enhance the Hispanic cultural value of respeto and encourage mutual, reciprocal patterns of communication between parents and adolescents may foster more positive family dynamics.

Programs for treating Latina adolescents at-risk for suicidal behavior should focus on enhancing the interdependent negotiation of parent-child expectations, particularly surrounding issues of dating, sexuality, and family responsibilities.

Acknowledgments

Support for this paper was provided by grant R01 MH070689 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Luis H. Zayas. Additional support was provided by the Center for Latino Family Research. We extend our gratitude to the adolescent girls and their families who participated in this study.

Footnotes

“Estamos tratando de hacer lo mejor para nosotros.”

“Algún día se ira a dar cuenta que no le conviene.”

“No me pude dormir….Cogí mi muchachita y la esperé por la mañana….La levanté a horario escolar…y todo. Cuando iba a salir que me dijo me voy. Le digo no, tú no vas para la escuela. Tú vas conmigo para donde la pediatra.”

“Yo soy bastante celosa en ese sentido. Si ella sale, sale conmigo. Si no, no sale con nadie.”

“En mi casa, no nos ayudamos entre todos, y eso debería, deberíamos ayudarnos, contarnos los problemas todos y tratar de ayudarnos tratar de salir adelante juntos, pero en mi casa uno vive su propia vida.”

“Yo lo quiero es agarrarla y desbaratarla….Que yo si tengo que agarrarla y darle, le doy. La agarro y si la tengo que ahorcar la ahorco. Estoy pidiendo a Dios que me ayude a calmarme para no…agarrarla y matarla. Yo le digo a ella que yo te di la vida y yo te la quito.”

“Le digo, ‘de qué manera nos estamos ayudando? Yo siento que estoy poniendo de mi parte pero tú no. Tú lo estás empeorando todo mal.’”

Contributor Information

Lauren E. Gulbas, Dartmouth College and Center for Latino Family Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Luis H. Zayas, Center for Latino Family Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Allyson P. Nolle, South Side Day Nursery in St. Louis and Center for Latino Family Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Carolina Hausmann-Stabile, Center for Latino Family Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Jill A. Kuhlberg, Center for Latino Family Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Ana A. Baumann, Center for Mental Health Services and Center for Latino Family Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Juan B. Pena, Center for Latino Family Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

References

- Ayres L, Kavanaugh K, Knafl KA. Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:871–883. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013006008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin S, Ryan G, Gelberg L. What pediatricians can do to further youth violence prevention—A qualitative study. Injury Prevention. 1999;5:53–58. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne JE. The management of patients post-suicide attempt in an urban municipal hospital. Psychiatria Fennica. 1983:45–54. Suppl. [Google Scholar]

- Blair S, Blair M, Madamba A. Racial/ethnic differences in high school students' academic performance: Understanding the interweave of social class and ethnicity in the family context. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1999;30:539–555. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP. ANTHROPAC (Version 4.0) Natick, MA: Analytic Technologies; 1996. Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Goldstein CE, Kolko D, Allan MJ, Allman CJ, Zelenak JP. Risk factors for adolescent suicide: A comparison of adolescent suicide victims with suicidal inpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45(6):581–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800300079011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Fernandez Y, Cortes DE. Incorporating the cultural value of respeto into a framework of Latino parenting. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(1):77–86. doi: 10.1037/a0016071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona PG, Nicholson BC, Fox RS. Parenting among Hispanic & Anglo-American mothers with young children. Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;140:357–365. doi: 10.1080/00224540009600476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Surveillance Summary. SS-4. Vol. 57. Author; 2008. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5(2):113–132. doi: 10.1023/a:1015420503275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez VA, Carter SJ. Parenting interventions adpated for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Wesport, CT: Praeger; 2000. pp. 203–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Pettit GS, Woodward L. Does father absence place daughters at special risk for early sexual activity and teenage pregnancy? Child Development. 2003;74(3):801–821. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R, Fretz R, Shaw L. Writing ethnographic field notes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein J, Donenberg G, Martinovich Z. Maternal control and adolescent depression: Ethnic differences among clinically referred girls. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;65:1036–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Formoso D, Gonzales NA, Aike LS. Family conflict and children's internalizing and eternalizing behaviors: Protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(2):175–199. doi: 10.1023/A:1005135217449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C, Skay C, Sieving R, Naughton S, Bearinger LH. Family and racial factors associated with suicide and emotional distress among Latino students. Journal of School Health. 2008;78(9):487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera A, Dahlblom K, Dalgren L, Kullgren G. Pathways to suicidal behavior among adolescent girls in Nicaragua. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(4):805–814. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl KA, Ayres L. Managing large qualitative data sets in family research. Journal of Family Nursing. 1996;2(4):350–364. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J. Family management style and the challenge of moving from conceptualization to measurement. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nurses. 2006;23(1):12–18. doi: 10.1177/1043454205283585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marttunen MJ, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK. Precipitant stressors in adolescent suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(6):1178–1183. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan SS. Father absence and the welfare of children. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with divorce, single parenting, and remarriage: A risk and resiliency perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaurn Associates; 1999. pp. 117–146. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded source book. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki EK. Epidemiology of suicide. In: Jacobs DG, editor. Harvard Medical School guide to suicide assessment and intervention. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1999. pp. 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis (Version 7) Cambridge, MA: QSR International; Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- Razin AM, O'Dowd MA, Nathan A, Rodriguez I, Goldfield A, Martin C, Goulet L, et al. Mosca J. Suicidal behavior among inner-city Hispanic adolescent females. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1991;13:45–58. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(91)90009-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, Thomas N, Horner S, Resnick MD, Beuhring T. Correlates of recent suicide attempts in a triethnic group of adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33(4):361–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. Rockville, MD: 2003. Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-22, DHHS Publication No. SMA 03–3836. Author. [Google Scholar]

- Tesch R. Qualitative research analysis types and software tools. New York, NY: Falmer Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Trautman EC. Suicide attempts of Puerto Rican immigrants. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1961;35:544–545. doi: 10.1007/BF01573622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner BM. Family risk factors for child and adolescent suicidal behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(2):246–298. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Bright C, Alvarez-Sanchez T, Cabassa LJ. Acculturation, familism and mother-daughter relations among suicidal and non-suicidal adolescent Latinas. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30(3–4):351–369. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Gulbas LE, Fedoravicius N, Cabassa LJ. Patterns of distress, precipitating events, and reflections on suicide attempts by adolescent Latinas. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(11):1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Lester RJ, Cabassa LJ, Fortuna LR. Why do so many Latina teens attempt suicide? A conceptual model for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(2):275–287. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]