This study investigates colleague–colleague relationships within life sciences departments and how they may promote teaching reform. The authors found that discipline-based education researchers are perceived as promoting changes among colleagues in views about teaching and teaching practices. Other faculty may also be leveraged to support change.

Abstract

Relationships with colleagues have the potential to be a source of support for faculty to make meaningful change in how they teach, but the impact of these relationships is poorly understood. We used a mixed-methods approach to investigate the characteristics of faculty who provide colleagues with teaching resources and facilitate change in teaching, how faculty influence one another. Our exploratory investigation was informed by social network theory and research on the impact of opinion leaders within organizations. We used surveys and interviews to examine collegial interactions about undergraduate teaching in life sciences departments at one research university. Each department included discipline-based education researchers (DBERs). Quantitative and qualitative analyses indicate that DBERs promote changes in teaching to a greater degree than other departmental colleagues. The influence of DBERs derives, at least partly, from a perception that they have unique professional expertise in education. DBERs facilitated change through coteaching, offering ready and approachable access to education research, and providing teaching training and mentoring. Faculty who had participated in a team based–teaching professional development program were also credited with providing more support for teaching than nonparticipants. Further research will be necessary to determine whether these results generalize beyond the studied institution.

INTRODUCTION

College biology instructors are being asked to reconsider traditional teaching strategies in favor of evidence-based teaching strategies (Freeman et al., 2014). The most prominent call for reform in the life sciences, called Vision and Change, urges faculty to focus on teaching core concepts and competencies and to integrate more opportunities for students to be active participants in their learning and in the practice of science (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011). Instructors have also been encouraged to teach in ways that increase student motivation and metacognition, which in turn can influence students’ learning and achievement in science (e.g., Glynn et al., 2007; National Research Council [NRC], 2012; Tanner, 2012; Stanton et al., 2015). Despite these calls for changing undergraduate biology instruction, traditional teaching strategies remain common (NRC, 2012), and little is known about how to help college biology faculty reform their teaching to align with recommendations.

Colleague–colleague relationships have the potential to facilitate reform in undergraduate biology education. Colleagues are embedded in the same institutional context, so they can help one another navigate local constraints to achieve change (Henderson et al., 2011). Collegial relationships are also enduring and thus are well positioned to provide the long-term support needed to change one’s teaching (e.g., Andrews and Lemons, 2015). Colleagues are accessible to faculty who may not seek teaching support outside their departments or institutions. Furthermore, interpersonal relationships—especially face-to-face interactions—are important in catalyzing changes in strongly held beliefs (Rogers, 2003), which is needed to engender meaningful and sustained change in teaching (Henderson et al., 2011).

Existing teaching reform efforts already take advantage of collegial relationships. For example, the National Academies Summer Institutes on Undergraduate Education, a 5-d workshop on evidence-based teaching strategies, enrolls faculty only in departmental teams in order to build collegial support networks that continue when participants return to their institutions. Faculty learning communities (FLCs), which are small groups of faculty who meet regularly over an extended period of time with the objective of improving their teaching (Cox, 2004), are also designed to take advantage of collegial support. FLC participants have reported that the experience helps them change their teaching, for instance, by building their confidence in experimenting with different teaching strategies (Tovar et al., 2015) and promoting use of student-centered teaching practices (Polich, 2008; Light et al., 2009).

Academic colleagues provide other forms of support for one another’s work, but support for teaching may be especially important. Colleagues provide mentoring, ties to powerful people, emotional support, and opportunities for professional advancement (e.g., van Eck Peluchette and Jeanquart, 2000; van Emmerik and Sanders, 2004). Support provided by colleagues is particularly influential for pretenure faculty (e.g., van Emmerik and Sanders, 2004; Pifer and Baker, 2013), but faculty at later career stages also benefit from interactions with colleagues (van Eck Peluchette and Jeanquart, 2000). Collegial support for teaching may be even more important than support for other aspects of faculty work, such as research, because graduate and postdoctoral training in science often fail to provide adequate preparation for teaching (Austin, 2002; Richlin and Essington, 2004; Foote, 2010; Hunt et al., 2012). Faculty end up learning about teaching “on the job,” where colleagues may be the primary sources of information, educational materials, inspiration, and encouragement.

Theoretical traditions from other disciplines provide insight regarding the role of social relationships in education reform. The construct of “opinion leaders” is a potentially useful lens for investigating how colleagues impact one another’s teaching practices. This construct hails from communication studies, a discipline with a rich history of investigating how individuals within organizations adopt innovations (e.g., Rogers, 2003). From this perspective, evidence-based teaching strategies can be considered “innovations” and academic departments are “organizations.” Most organizations have opinion leaders who are particularly influential in whether or not other members of an organization adopt an innovation (Rogers, 2003). Opinion leaders are able to influence others’ attitudes or overt behavior through informal interactions, and they do so with relative frequency (Rogers, 2003). In an organization oriented to change, opinion leaders tend to be innovators, whereas organizations opposed to change may have opinion leaders who are strong advocates of traditional practices (Rogers, 2003). We posit that there are departmental opinion leaders who have significant potential to influence their colleagues’ views about teaching and teaching practices.

Social network theory allows for the examination not only of who the key players are within an organization (e.g., opinion leaders) but also of which organizational relationships are important for sharing resources and producing outcomes (Burt, 1992; Granovetter, 1973). We focus in particular on identifying the networks related to undergraduate teaching within departments (i.e., who is interacting with whom about teaching) and characterizing the quality and influence of the relationships that bind each network together (i.e., what resources are shared, and to what end). As Cross and Borgatti (2004) argue, this approach has the potential to reveal individual and departmental “potential to recognize, assimilate, and take action on new problems or opportunities” (p. 138), namely, to improve undergraduate teaching.

Colleague–colleague relationships could be leveraged to encourage and aid faculty in changing their teaching and improving student learning. However, we lack empirical evidence regarding the nature and outcomes of colleague–colleague interactions about undergraduate teaching in the life sciences. Without this knowledge, we are ill equipped to help faculty and departments take advantage of the influence and assistance colleagues could provide to one another, and we are likely missing opportunities to positively impact undergraduates’ learning and success.

Here, we present an exploratory study that examined how life sciences faculty at a research university interact with and benefit from departmental colleagues regarding undergraduate teaching. The department is a promising system for changing teaching in academia, because teaching assignments and course development generally occur within departments, hiring and retention decisions begin in the department, and departments have their own cultures and practices (e.g., Austin, 1996; Silver, 2003; Wieman et al., 2010). Therefore, we conducted an in-depth study of colleague–colleague interactions in four life sciences departments within a single institution. This institution is categorized by the Carnegie classification system as having “very high research” activity, which is the most research-focused designation for higher education institutions (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 2011). We began our investigation of the role of colleague–colleague relationships in teaching reform at this type of university because research-focused institutions are expected to have environments particularly unsupportive of teaching (e.g., Rice and Austin, 1990; Knorek, 2012). Other institution types, such as small liberal arts colleges, have a stronger record of dedicating institutional energy and resources toward supporting faculty as teachers (e.g., Rutz et al., 2012). Investigating this single institution allowed us to study more than 110 faculty members in multiple departments while controlling for differences that might exist across institutions.

This study system was also suitable, because each department we studied employed tenure-track discipline-based education researchers (DBERs). Hiring DBERs in science departments is becoming increasingly common (e.g., Bush et al., 2008, 2011), but little is known about the impact of DBERs within departments. Two goals that have been described for these hires are improving undergraduate science education and cultivating departmental culture change toward a focus on education in the sciences (Bush et al., 2015). Understanding how faculty perceive, interact with, and are affected by DBERs will help us better understand the impact of these types of hires. We did not specifically design this study to investigate DBERs in departments but rather to study collegial relationships in departments that include DBERs, so we did not explicitly ask participants about interactions with DBERs. Therefore, it is a powerful investigation of whether and how DBERs are perceived to influence faculty to change their teaching.

We used a mixed-methods approach, collecting and analyzing both survey and interview data, to address the following research questions:

To what degree do colleague–colleague interactions about undergraduate teaching occur and between whom?

Who provides resources for undergraduate teaching as a result of collegial interactions?

Who influences colleagues to change their views and behaviors related to undergraduate teaching (i.e., who are opinion leaders), and how have they influenced colleagues to change?

METHODS

Participants

We collected data from faculty in four departments using an online survey in Fall 2013. We also collected data from faculty in three of the four departments through one-on-one interviews in Spring and Summer 2014. These departments employ very few non tenure-track faculty, so the results presented here are limited to assistant, associate, and full professors, as well as emeritus faculty who were still active in the department at the time of data collection. We invited all faculty in the four target departments to participate by email (n = 113). We launched a friendly competition among departments by promising home-baked treats at three consecutive faculty meetings for the department with the highest response rate. For the interviews, we strategically recruited a sample of professors of all ranks. To maintain the confidentiality of our participants, we have assigned each department a color as a pseudonym. The University of Georgia Institutional Review Board determined that this study met the criteria for exempt review procedures.

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

Survey Data Collection.

We collected survey data to gain comprehensive, quantitative data from faculty regarding who interacted with whom about undergraduate teaching, what resources they garnered from these interactions, and what outcomes they experienced as a result of these interactions. Using an online survey in Fall 2013, we asked faculty in the four target departments to select their department and then presented a list of departmental colleagues and asked participants to: “Please select the people in your department with whom you interact about teaching undergraduate biology. Interacting includes everything from talking about teaching to sharing resources to receiving and giving feedback.” For subsequent survey questions, each respondent saw only the names selected in this first question. We asked respondents to indicate how often they interacted with each person and “what outcomes you have experienced as a result of interacting with this person about teaching undergraduate biology.” Respondents could indicate as many of the listed items as were applicable (Table 1). Within this list, it is useful to differentiate “resources,” which are something that can be received in a social interaction, and “changes” occurring as a consequence of a social interaction. Respondents could indicate that they “engaged in conversation” with the individual or experienced “no outcomes” as a result of interacting with the individual; these responses are not considered in our analyses as they do not represent resources or change (Table 1).

Table 1.

Options of resources and changes resulting from collegial interactionsa

| I received instructional materials (e.g., curricula, lessons, PowerPoints). |

| I received social support (e.g., empathy, reassurance, commiseration). |

| I received useful feedback or ideas about my teaching. |

| I received information (e.g., advice, ideas). |

| I changed my views about teaching. |

| I made changes to my teaching practice. |

| I engaged in conversation about teaching. |

| I experienced no outcomes. |

aSurvey respondents were prompted to indicate which outcome(s), if any, they had experienced as a result of interacting with each colleague with whom they reported interacting about undergraduate teaching.

We also asked respondents to “please list any other people employed at [your institution] with whom you interact about teaching undergraduate biology at least monthly.” Respondents could list up to five people. Respondents reported the resources received and changes experienced as a result of interacting with these colleagues.

Other Data Collection.

We collected publicly available data about each faculty member in all four departments to complement survey data. We determined academic rank in Fall 2013 (i.e., assistant, associate, or full professor), gender, and whether or not a faculty member was a DBER. We defined DBERs as faculty whose jobs have a research expectation related to biology education. We also determined whether each faculty member had participated in a regional teaching professional development program using a list provided by the program organizers. This program is relevant to our investigation, because it accepts teams from within a department and may therefore facilitate the development of teaching-related relationships among departmental colleagues. Hereafter, we refer to this program as “Regional Teaching PD.”

Social Network Analysis.

We used social network analyses (SNA) to determine the degree to which faculty interacted with their colleagues about teaching (research question 1), including the characteristics of their teaching-related networks and what individual attributes were associated with interactions. SNA is useful for elucidating the social structure of a community, including the determinants of the structure of relationships among members of the community (Hawe et al., 2004; Grunspan et al., 2014). In this study, we treated each department as a community or network. Networks consist of actors, and any two actors within a network are a dyad (Hawe et al., 2004; Grunspan et al., 2014). The relationships between actors are called ties, and the focus of our analysis is on ties. SNA allows us to investigate the characteristics of an individual faculty member that are associated with interacting with colleagues about teaching, and the characteristics of faculty members in a dyad that make an interaction about teaching more likely.

Preparing the Network Data.

We constructed a network matrix for each department using responses to the survey question asking respondents to indicate which departmental colleagues they interacted with about teaching. Each matrix included all faculty in the department. Nonresponse can be an issue in SNA, because it can result in missing network information. However, a lack of response does not mean that actors are left out of the network, because respondents can report ties to nonrespondents (Borgatti and Molina, 2003). Missing data on ties can be reconstructed through a process called “symmetrizing” that assumes a tie exists if it is reported by at least one member of a dyad (Stork and Richards, 1992). Before symmetrizing, it is important to determine whether assuming reciprocal ties is reasonable. For our study, the phrasing of our survey question supports symmetrizing, because we asked respondents to report “with whom you interact” about undergraduate teaching, which implies undirected or symmetrical ties (i.e., if I interact with you, then you interact with me). This is distinct from a directed network, such as a mentoring network (e.g., if I mentor you, you do not necessarily mentor me). In addition, determining whether an interaction has occurred is relatively objective. In contrast, asking respondents to nominate “best” friends would rely heavily on individual perceptions and judgments, meaning two participants would be less likely to agree on whether they were best friends or not. Stork and Richards (1992) suggest that assuming reciprocal ties is justified if actors who responded to the survey (respondents) are similar to actors who did not respond to the survey (nonrespondents). We followed their approach for comparing respondents and nonrespondents, and the results support our decision to symmetrize the data (see the Supplemental Material for detailed descriptions of these comparisons).

Even after symmetrizing the data, we were missing data for some dyads, because neither person responded to the survey. We quantified this as “missingness,” or the percent of dyads for which we have no data out of all possible dyads in a network (Table 2). Missing data have a negative effect on network mapping and model estimation, because missing data can lead to underestimating the strength of relationships. According to Costenbader and Valente (2003), the ranking of an actor based on being nominated is relatively stable even at a low sampling level, such as 50% missingness. All four of our networks have missingness below 50%, but we chose to proceed conservatively. The Yellow department had 44% missingness, meaning that we lacked data from both members of a dyad for 44% of the possible dyads within the department. Therefore, we calculated simple network metrics, but did not fit complex models for this department. The other departments were missing data from no more than 30% of the possible dyads in the department (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of department networksa

| Department | Reciprocity (%) | Missingness (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Green | 55 | 12 |

| Yellow | 54 | 44 |

| Red | 48 | 30 |

| Blue | 43 | 18 |

aReciprocity within data from survey respondents was sufficiently high to assume reciprocity among all departmental colleagues. Missingness is calculated after assuming reciprocity and indicates the percent of ties in a network for which we have no data.

Calculating Simple Metrics to Characterize Networks.

We used network density and transitivity to characterize collegial interactions in each department. One of the most widely used concepts in network analysis is “density.” Density describes the general level of linkage among actors in a network, and it is one way to quantify group cohesion. The more actors who are connected to one another, the denser the network will be, and the more cohesive the network will be. Evidence has shown that a dense web of interactions facilitates both information exchange and knowledge transfer (Burt, 1987; Reagans and McEvily, 2003). To measure network density, we calculated the incidence of interactions among all possible dyads in a network (Friedkin, 1981) using the software UCINET (Borgatti et al., 1991). It is defined as the proportion of ties that exist out of the total number of ties possible. The formula for the density is

|

where l is the number of ties present and n is the number of actors the network contains.

This measure can vary from 0 to 1, with no connections among actors in a network corresponding to a density of 0 and every actor being connected to every other actor corresponding to a density of 1.

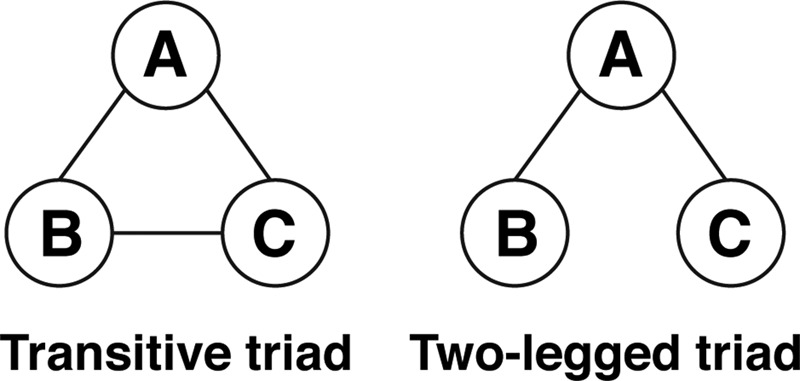

Another well-known small-scale attribute of social networks is transitivity, which is defined as the tendency of two actors to be connected to each other if they share a mutual neighbor (Holland and Leinhardt, 1971). Transitivity has been nicely described in the conventional wisdom that “friends of my friends are my friends.” Transitivity deals with triads, which are connections among three actors. With undirected network data like ours, there are four possible types of triadic relations (no ties, one tie, two ties, or all three ties). Counts of the relative prevalence of these four types of relations across all possible triads provides a sense of the extent to which a network is characterized by “isolation,” “couples only,” “structural holes” (i.e., where one actor is connected to two others who are not connected to each other), or “clusters.” We are particularly interested in the proportion of triads that are transitive, compared with triads that are two-legged (Figure 1). Two-legged triads could be thought of as “potentially transitive” triads, because they could be made transitive with just one more tie.

Figure 1.

Two types of triads, which are ties among three people. Transitivity measures the proportion of these two types of triads that are transitive (i.e., closed) triads.

Transitivity implies interactions are largely confined to friends and to friends of friends. High transitivity tends to reinforce group norms, and low transitivity allows for multiple viewpoints (Quardokus and Henderson, 2015). A meaningful way to measure transitivity for each network (i.e., department) is to calculate the number of closed (i.e., transitive) triads divided by the sum of all closed triads and all two-legged triads (i.e., potentially transitive). Transitivity ranges between 0 and 1; it is 1 for a perfectly transitive network, where all triads are closed. Seen in this way, a transitivity index of 0.4 means 40% of all transitive and two-legged triads are transitive.

Exponential Random Graph Models.

We used exponential random graph models (ERGMs) to make statistical inferences about the likelihood of observing particular patterns of interactions as a result of chance. Building on statistical exponential family models (Strauss and Ikeda, 1990), ERGMs recognize the lack of independence among ties between actors in the data. For instance, the relationship between actor A and actor C may be contingent upon the relations between actor A and actor B. So instead of focusing on individuals as the unit of analysis, ERGMs predict the likelihood of an interaction (i.e., a tie being present) based on individual, dyadic, and local network properties. For example, faculty who engaged in the Regional Teaching PD may have more interactions (i.e., ties) with departmental colleagues than would be expected if relationships occurred completely at random. This is an individual-level property of a tie. Dyadic properties take into account how the individual characteristics of both members of a tie are associated with the presence of a tie, such as whether female faculty are more likely to have ties with other female faculty than with male faculty. ERGMs can include parameters representing extraneous structural forces, such as tendencies to reciprocate ties or complete a two-legged triad. These processes contribute to interaction patterns found in the data beyond the individual characteristics and dyad dynamics.

We used the network and ergm packages in R for this analysis. The ergm package allows maximum-likelihood estimates of ERGMs to be calculated using Markov chain Monte Carlo (Robins et al., 2007; Goodreau et al., 2008; Hunter et al., 2008). We fit separate models for the Red, Blue, and Green departments. We assumed that teaching-related ties were generated by local social processes and that these social processes may depend on the surrounding social environment (i.e., on existing relations). To reflect all the social processes that might contribute to the interaction patterns observed in our data, we examined the following individual attributes: gender, academic position, position type (i.e., DBER or non-DBER), and participation in Regional Teaching PD. To examine the same variables at a dyadic level, we included node (i.e., actor) match terms in our models to capture the effect of the two members of a dyad having the same attributes. The phenomenon of people interacting with people similar to them at higher rate than those who are dissimilar is called homophily. For example, we tested whether junior faculty reported interacting at a higher rate with other junior faculty compared with their senior counterparts. We also included an edges term, which controls for the baseline probability of a tie, or the proportion of ties in a network that exist out of all possible ties.

Regression Analysis.

All regression analysis was completed in R, version 3.1.2. We used two generalized linear regression models to determine the attributes associated with providing resources for teaching (research question 2), and the attributes associated with prompting colleagues to change their views about teaching and teaching practices (research question 3). We counted each type of resource that a faculty member was reported to provide to each survey respondent. A faculty member who was reported to provide feedback to three survey respondents was counted as providing three resources, as was a faculty member who provided three different resources (i.e., feedback, instructional materials, and social support) to a single survey respondent. We used the same strategy to calculate the number of changes a faculty member was reported to have caused.

Both regression models included a common set of explanatory variables: gender, academic rank, position type, and participation in Regional Teaching PD. The total number of resources a faculty member was reported to provide or the number of change occurrences caused may be impacted by the number of survey respondents from that department, which varied from 10 to 16 across departments. We included department as an explanatory variable in our models to control for this potential influence. We also controlled for whether or not a faculty member was a survey respondent by including this variable. We hypothesized that the exchange of resources would predict changes in teaching or views about teaching. Therefore, the model examining change included the number of resources provided as an additional explanatory variable.

We used existing literature and exploratory analyses to decide what regression analyses were most appropriate for achieving our study objectives, given the nature of our data. We asked faculty to report their interactions within their departments, creating a lack of independence among data collected from survey respondents in the same department. Mixed models can account for this sort of hierarchical data structure by including the nesting factor (i.e., department) as a random effect. However, we studied four departments, and in cases with fewer than five groups, multilevel modeling does not provide an advantage over a classical regression model that includes groups as fixed effects (Gelman and Hill, 2007). Therefore, we controlled for department by including it as an explanatory variable in both models.

Regression Models.

We used a zero-inflated Poisson model for the teaching resources data (UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group, n.d.). A zero-inflated negative binomial model includes two different models: a binary model to account for excess zeros and a count model. The binary model improves the model fit but does not provide results that inform our research questions. We include the estimated intercept from this model in our results table (see Table 7 later in the article) but do not discuss it further. We present the back-transformed regression coefficients and confidence intervals. We calculated bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals using the bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) method with 10,000 replicates (Efron, 1987). We used a Poisson model to examine the associations between individual attributes and reports of causing change. We back-transformed regression coefficients and calculated 95% confidence intervals.

Table 7.

Results of generalized linear regression modelsa

| Response (dependent) variable | Number of resources provided | Number of changes caused |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept for count model | 2.82** (1.31, 5.94) | 0.14*** (0.06,0.32) |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.72 (0.42, 1.19) | 1.85* (1.16, 3.04) |

| Academic rankb (full vs. assistant) | 1.70* (1.08, 2.62) | 1.76* (1.03, 3.06) |

| Academic rank (associate vs. assistant) | 2.64*** (1.57, 4.98) | 1.12 (0.68, 1.88) |

| Position type (DBER vs. non-DBER) | 2.09* (1.06, 4.10) | 2.90*** (1.62, 5.24) |

| Teaching PD (participant vs. nonparticipant) | 0.98 (0.5, 1.74) | 2.03* (1.14, 3.60) |

| Survey participant (Y vs. N) | 1.90** (1.23, 3.08) | 1.43 (0.98, 2.12) |

| Total resources provided | NA | 1.15*** (1.13, 1.19) |

| Department Yellow vs. Blue | 1.17 (0.72, 2.12) | 0.58* (0.36, 0.92) |

| Department Red vs. Blue | 1.01 (0.45, 2.40) | 0.72 (0.39, 1.30) |

| Department Green vs. Blue | 1.09 (0.68, 1.89) | 0.37** (0.20, 0.68) |

| Intercept for binary model | 2.48*** (0.81, 3.68) | NA |

aEstimates and 95% confidence intervals of the association between explanatory variables and reports of teaching resources provided and change caused as a result of interactions about undergraduate teaching with departmental colleagues.

bIn these models, assistant professor and the Blue department are set as the reference levels of the academic rank variable and department variable, respectively. One can fit another model with different reference levels to determine the relationship between these levels and the response variables. We examined all of these. The only significant results were associate vs. full professors for resources provided: 0.65*(0.35, 1.11) and Red vs. Green for change caused: 1.95*(1.10, 3.49). Setting a different reference level does not change other results, except the estimate of the intercept.

*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

Interview Data Collection.

We conducted hour-long, one-on-one interviews with faculty from three of the four departments in order to acquire rich descriptive data from faculty regarding colleague–colleague interactions about undergraduate teaching. The interviews were conducted as part of a larger investigation of the working environments in which college biology faculty make decisions regarding undergraduate teaching. The interviews were semistructured, meaning that the interviewers asked the same questions of all participants while remaining flexible about the order of questioning and prompting interviewees for more detail as needed (full protocol in the Supplemental Material). Although the interview protocol did not specifically ask about interactions with departmental colleagues, many of the questions elicited information about the faculty members whom interviewees perceived to be most influential regarding teaching. Two questions elicited a greater number of relevant quotes than the others: “What is going on in your department that helps you to be a good teacher?” and “Is there anyone in your department who you would say is particularly influential to undergraduate teaching?” Both T.C.A. and E.P.C. conducted the interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Two of the authors are DBER faculty, and that fact was not hidden from research participants. We took several steps to mitigate the potential bias this could introduce to our work. Aside from our names on recruitment communications and on the consent form, there was nothing in the survey to cue respondents to think about DBER faculty. At no point in the survey or interviews did we ask any questions specifically about DBER faculty (see the Supplemental Material). One of the interviewers (T.C.A.) was a DBER faculty member, and this could have cued interview participants to think about DBER faculty more than they otherwise would have. However, this investigator had been in her position for less than a year when the interviews were conducted, and she did not conduct any interviews with faculty she had previously met. Interviews with faculty with whom she had previously interacted were scheduled and conducted by the other interviewer. We opted not to collect interview data from the department to which she belonged, which is why we present interview data from only three departments.

Qualitative Data Analysis.

Qualitative analysis allowed us to elucidate how colleagues influence change in teaching views and behaviors (research question 3).

Identifying Opinion Leaders.

We used the results of the survey data to identify faculty members who were reported to prompt the most change in views about teaching or teaching practice. To identify the faculty who engendered the most change, we calculated the median and SD of the number of change occurrences attributed to each faculty member by survey respondents in each department. We then calculated the number of change occurrences equal to the median plus two times the SD. Any faculty member in a department who was reported to have caused a number of change occurrences equal to or higher than this value was considered an “opinion leader” and was investigated further. In each department, the opinion leader with the smallest number of change occurrences still had at least twice as many change occurrences as the next highest count in the department. For example, in one department the three opinion leaders were credited with causing seven, nine, and 11 change occurrences, whereas the next most influential faculty member was credited with only three change occurrences. This provides further support to our claim that department members perceived these individuals as distinctive in the degree to which they influence teaching. We limited our qualitative investigation to only those faculty who were reported as contributing to substantial change in the department.

Extracting Relevant Data.

We then used Atlas.ti to analyze portions of interview transcripts in which participants discussed the contributions of the identified opinion leaders. We conducted this analysis for the Yellow, Green, and Red departments only (i.e., those for whom we had collected interview data). We used two strategies to identify sections of interview transcripts that discussed opinion leaders. First, previous coding undertaken for the larger project included identifying and marking any section of text that mentioned a DBER faculty member, which was useful, because many of the opinion leaders were also DBER faculty. The goal of the previous analysis was much broader than simply identifying sections of text about opinion leaders, so our strategy was more thorough than would have been necessary simply to identify quotes relevant to this study. Three researchers worked to code transcripts, and at least two researchers worked on the analysis of each transcript. We first coded as a team, discussing to reach consensus regarding which sections of text referred to DBER faculty. Later a single researcher analyzed a transcript, and then a second researcher read the transcript and checked each code to determine whether codes should be added or removed or whether the section of text designated by a code included all relevant and no extraneous information. If the second researcher disagreed with any part of the analysis conducted by the first researcher, they discussed until they reached consensus. Interviews analyzed in this way were divided so that the researcher who checked the analysis was the person who had conducted the interview. This was useful, because the second researcher was familiar with the interview and therefore was able to efficiently identify ideas that the initial researcher had missed and also to question the interpretation of data.

Our second strategy included searching the text of all transcripts for any place that an opinion leader’s name was mentioned and marking these sections of text. Not every mention of an opinion leader was useful, because some did not focus on social relationships among faculty. For example, there were quotes about the hiring and promotion process for DBER faculty that were not relevant to this study. Rather, we focused on quotes about opinion leaders that were relevant to our research questions.

Thematic Text Analysis.

With a complete list of quotes about opinion leaders in hand, we conducted thematic text analysis to detect patterns of ideas expressed by interviewees. We sought to compare opinion leaders with one another to identify similarities and differences within this group. We also aimed to identify similarities and differences among departments by comparing opinion leaders in one department with those in the other two. We analyzed data at two different grain sizes to accomplish these aims. We read and reread full quotes, which can be considered “raw” data, and labeled these quotes to indicate themes. We created a cross-comparison table by generating short synopsis statements to represent each quote. Each row of the table is one case (i.e., opinion leader), and the columns of the table represent major themes in the data set. The identity of these themes emerges and is refined as researchers add synopsis statements to the table. Essentially, the table is an organizational structure for identifying patterns in the data and allowed us to better compare opinion leaders.

All qualitative analyses were iterative and collaborative. One researcher (T.C.A.) spearheaded the analysis process, and another researcher (E.P.C.) cross-checked the data and results repeatedly throughout the process. Cross-checking involved reading all quotes and comparing them with the synopsis statements and the Results section of the manuscript with the goal of identifying anything that was missing, incomplete, or extraneous. T.C.A. and E.P.C. engaged in a number of discussions about the emerging themes throughout this process. Additionally, three experienced qualitative researchers reviewed the analysis and results at multiple points in the process.

Quotes about opinion leaders often included their names, which we have replaced with pseudonyms. To protect the anonymity of our participants, we do not attribute quotes to specific interviewees. We assigned all DBER opinion leaders pseudonyms beginning with the letter “D” and all non-DBER opinion leaders pseudonyms beginning with the letter “N” to allow readers to better recognize the differences between how group members were perceived by their colleagues. All of our qualitative analysis focused on opinion leaders, so the results apply to that select group only. Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity and grammar. We have also excised sections of quotes that are not relevant for the sake of brevity, as well as sections that have the potential to reveal the identity of interviewees or opinion leaders.

RESULTS

This exploratory study examined faculty within one research institution. Response rates to the survey ranged from 33% of faculty in the Yellow department to 63% of faculty in the Green department, with an average survey response of 46% across all four departments (Table 3). These response rates are similar to those achieved in another investigation collecting network data from college faculty (Quardokus and Henderson, 2015). Response rates for interviews were somewhat higher, with an average of 57% of contacted faculty participating in an interview (Table 3). The data presented in this study have been collected from a total of 59 faculty members: 27 provided both survey and interview data, 25 completed only the survey, and seven only participated in an interview.

Table 3.

Recruitment and participation by departmenta

| Department | Faculty contacted for survey | Survey participants | Survey response rate (%) | Faculty contacted for interview | Interview participants | Interview response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | 19 | 12 | 63 | 19 | 13 | 68 |

| Yellow | 43 | 14 | 33 | 27 | 14 | 52 |

| Red | 23 | 10 | 44 | 21 | 11 | 52 |

| Blue | 28 | 16 | 57 | None | NA | NA |

| Total | 113 | 52 | 46 | 67 | 38 | 57 |

aFaculty were recruited from four life sciences departments for an online survey and from three departments for one-on-one interviews.

Research Question 1: To What Degree Do Colleague–Colleague Interactions about Undergraduate Teaching Occur and between Whom?

Across departments, survey respondents reported interacting with a median of 18% (SD = 19%) of their departmental colleagues about undergraduate teaching, but this value varied from 14% (SD = 21) in the Blue department to 30% (SD = 22) in the Red department. Interactions about undergraduate teaching did not occur frequently. More than 60% (n = 33) of survey respondents had no departmental colleagues with whom they interacted about undergraduate teaching on a weekly basis, and 31% (n = 16) had no departmental colleagues with whom they interacted about teaching even once per month (Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequency distribution of interactions with departmental colleaguesa

| Number of colleagues interacted with | Monthly or more often (%) | Weekly or more often (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 16 (31) | 33 (63) |

| 1 | 12 (23) | 10 (19) |

| 2 | 9 (17) | 4 (8) |

| 3 | 2 (4) | 3 (6) |

| 4 | 5 (10) | 1 (2) |

| 5 | 3 (6) | 1 (2) |

| 6+ | 5 (10) | 0 (0) |

aCount (percent) of survey respondents (n = 52) who report interacting with departmental colleagues at least once per month and at least once per week.

Survey respondents also reported few out-of-department colleagues with whom they interact about teaching regularly. Most survey respondents (n = 36, 68%) did not list anyone outside their departments with whom they interact at least once per month about undergraduate teaching. Just nine survey respondents (17%) reported interacting with out-of-department colleagues about undergraduate teaching on a weekly basis.

One group that stood out as well connected to out-of-department colleagues was faculty holding DBER positions. In fact, 57% of the reported social interactions with out-of-department colleagues were with DBER faculty from another department. About half of these connections were between a DBER and a non-DBER faculty member, and the other half were between two DBER faculty. These results indicate that DBER faculty are strongly connected to one another and are also responsible for many of the interdepartmental interactions about undergraduate teaching. Two staff from the Center for Teaching and Learning were each nominated once as an out-of-department colleague. Some nominations reflected personal relationships among faculty, such as spouses. Other relationships may have formed as a result of coparticipation in university-wide teaching-focused groups.

Overall, network data suggest that colleague–colleague relationships regarding teaching are relatively common in these departments, at least compared with other science departments. Network density ranged from 0.15 to 0.34. In comparison, a teaching network study of five science departments at another research-intensive university found network densities ranging from 0.06 to 0.216 (Quardokus and Henderson, 2015). It is important to note that density can be affected by both the size of network (i.e., as networks grow in size, density declines) and response rate (i.e., missing ties may contribute to a less dense network). Even taking this into account, there were differences among departments (Table 5). For example, the Red and Blue departments have a similar number of faculty (Red: 23; Blue: 28) and the response rate was higher for Blue (57%) than for Red (44%) (Table 3). Yet the density for Red department was nearly double that of Blue department (Table 4), indicating that the group cohesion about undergraduate teaching is greater for Red than for Blue.

Table 5.

Characteristics of departmental networks about undergraduate teachinga

| Department | Network density | Transitivity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Green (n = 19) | 0.29 | 17.9 |

| Yellow (n = 43) | 0.18b | 26.7b |

| Red (n = 23) | 0.34 | 30.5 |

| Blue (n = 28) | 0.15 | 12.6 |

aSurvey participants identified all departmental colleagues with whom they interact. Their nominations create a network of connections among faculty, and the degree of cohesion within the network is characterized by density. Transitivity relates to how efficiently information can be expected to travel through a network.

bThis value should be interpreted with caution, because this department had more missing data than the other departments.

Transitivity was highest in the Yellow and Red departments (Table 5). Recall that transitivity for a network is measured by the number of transitive triads divided by the sum of transitive triads and two-legged triads (Figure 1). The department with the lowest transitivity (Blue) had a transitivity score similar to departments investigated by Quardokus and Henderson (2015). The Green and Red department are similarly sized and have a similar density of ties, but transitivity is much higher in the Red department.

Network analysis using ERGMs revealed that both individual and dyadic attributes predicted the likelihood of a tie between departmental colleagues in some departments. The odds of male faculty interacting with colleagues was 0.35 times (95% CI: 0.18–0.67; p < 0.001) and 0.34 times (95% CI: 0.16–0.70; p < 0.01) lower than the odds of female faculty interacting with colleagues about undergraduate teaching in the Red and Green departments, respectively. Similarly, we observed that, in the same two departments, faculty who had participated in Regional Teaching PD were 1.97 times (95% CI: 1.14–3.42; p < 0.05) and 3.03 times (95% CI: 0.83–11.06; p < 0.09) more likely to interact with colleagues about undergraduate teaching than those who did not participate in this training. In only one department (Green) was academic rank associated with the likelihood of interactions regarding undergraduate teaching. Full and associate professors were 2.27 times (95% CI: 1.06–4.88; p < 0.001) and 7.3 times (95% CI: 2.56–21.29; p < 0.001) more likely to interact with colleagues about undergraduate teaching than were assistant professors, respectively. None of these attributes was associated with the likelihood of interacting with colleagues about teaching in the Blue department. Additionally, we did not find that having a DBER position increased the likelihood of interacting with colleagues about undergraduate teaching in any department. One potential explanation for this null finding is that there were only one or two DBER faculty per network (department), making the odds of identifying significant effects on this variable low.

Our models also estimated the likelihood of collegial interactions based on dyadic characteristics, such as gender homophily (individuals tend to interact more with same gender others than the opposite gender). We examined all the characteristics (gender, academic rank, participation in Regional Teaching PD, position type) at the dyadic level, but only one variable revealed a pattern. Rank homophily was present among associate professors in the Blue department; associate professors were 6.82 times (95% CI: 1.26–36.8; p < 0.05) more likely to interact with other associate professors in their departments than with colleagues of a different rank. In contrast, Green department full professors demonstrated a tendency against rank homophily. The likelihood of full professors interacting with one another was only about one tenth of the likelihood of them interacting with faculty of other ranks (95% CI: 0.02–0.52; p < 0.05).

Research Question 2: Who Provides Resources for Undergraduate Teaching as a Result of Collegial Interactions?

We asked survey respondents to indicate whether they received the following resources as a result of interacting with colleagues about undergraduate teaching: instructional materials, social support, feedback, and information (Table 1). Social support and information were the resources most commonly reported (Table 6). Respondents reported receiving no resources from 24% of the colleagues with whom they interacted about undergraduate teaching. The median number of resources that faculty were reported to have provided within their departments was 4 (SD = 6), and this value ranged from 0 (n = 31) to more than 20 (n = 4).

Table 6.

Frequency of outcomes reported to result from collegial interactions, ordered most to least commona

| Percent of outcomes reported | |

|---|---|

| Resources | |

| Social support | 25 |

| Information | 24 |

| Useful feedback | 18 |

| Instructional materials | 14 |

| Changes | |

| Changed teaching practices | 11 |

| Changed views about teaching | 9 |

aSurvey participants (n = 52) selected all outcomes they had experienced as a result of interactions with each departmental colleague with whom they reported interacting about undergraduate teaching.

After we controlled for department, several characteristics were significantly associated with the number of resources provided to colleagues: position type (i.e., DBER vs. non-DBER), academic rank, and having participated in this study (Table 7). Holding other variables constant, DBER faculty were reported to provide 2.09 times more resources for colleagues than non-DBER faculty. Compared with assistant professors, associate professors were reported to have provided 2.64 times more resources and full professors were reported to have provided 1.70 times more resources. Survey respondents were reported to provide 1.90 times as many teaching resources for faculty than nonrespondents (Table 7). We hypothesize this association is attributable to an unmeasured construct, such as interest in teaching, which makes a faculty member more likely to respond to a survey about undergraduate teaching and more likely to engage in productive interactions about teaching. The number of resources a faculty member was reported to provide did not vary by gender, department, or participation in Regional Teaching PD.

Research Question 3: Who Influences Colleagues to Change Their Views and Behaviors Related to Undergraduate Teaching (i.e., Who Are Opinion Leaders), and How Have They Influenced Colleagues to Change?

Ultimately, we are interested in colleagues as catalysts for improving undergraduate teaching. We asked survey respondents to identify departmental colleagues who had facilitated change in their views about teaching and/or their teaching practice. Respondents reported experiencing change as a result of collegial interactions less often than they reported receiving resources from these interactions (Table 6). More than half (57%) of the faculty in the departments we studied were not reported to have caused any survey respondents to change their teaching views or practices.

After controlling for department and whether or not an individual was a survey respondent, several characteristics were significantly associated with how many times a faculty member was reported to have prompted a colleague to change his or her views or teaching practices: position type (i.e., DBER vs. non-DBER), participation in Regional Teaching PD, gender, academic rank, and how many resources the faculty member was reported to provide to departmental colleagues (Table 7). DBER faculty were reported to have prompted almost three times as many occurrences of change in teaching views or practices than non-DBER faculty, and faculty who had participated in the Regional Teaching PD had prompted twice as many change occurrences as faculty who had not participated in the program (Table 7). Male faculty and full professors were reported to cause more change then their counterparts (Table 7). The number of resources for teaching that a faculty member provided to colleagues was significantly and positively associated with the number of times colleagues reported changing as a result of interacting with that faculty member. This result confirms that resources garnered from social interactions are important for effecting change. Survey respondents did not cause more change than nonrespondents (Table 7), indicating that interest in teaching (as inferred from status as a survey respondent) was not the same as driving change in teaching. Being influential, then, is more than being highly invested in undergraduate teaching. Faculty from some departments were more likely to be reported to cause change than others, including faculty from the Yellow department when compared with the Blue department, and faculty from the Red department when compared with the Green department. No other differences among departments were significant.

By examining the number of reported change occurrences caused by each faculty member, we identified nine opinion leaders in three departments: five DBER faculty and four non-DBER faculty. Across departments, opinion leaders caused 48, 67, and 69% of the change reported in the Green, Yellow, and Red departments, respectively. These values seem especially high when considering that opinion leaders are < 15% of the faculty in each department. These results reveal who influences colleagues to change their teaching but provide little insight as to why these individuals are influential or how they are impacting their colleagues, which is addressed by our qualitative investigation.

DBER versus Non-DBER Opinion Leaders

Results of the qualitative analysis showed that DBER and non-DBER opinion leaders derived their credibility and reputation among colleagues differently. Non-DBER opinion leaders, without exception, had a reputation for being excellent teachers. These faculty were noted by their colleagues for the positive influence they have on undergraduates:

“I never saw anybody’s teaching evaluations so off scale, I mean, [Nathan] must be doing something wonderful in his classroom, but it wouldn’t surprise me because he is a very enthusiastic guy.”

They were also described as exceptionally dedicated instructors, as described below:

“I would say if there was one person that I think is an astonishing teacher and puts more effort into it than anyone else, I would say it would be Natalie. She just has a natural gift.”

Most of the non-DBER opinion leaders had many years to build their reputations within their departments. The median number of years they had been members of their departments was 21 (SD = 17). One of the four non-DBER opinion leaders had been active in the department for more than 40 yr and another for almost 30. Neither of these two faculty had had active research labs in many years. Despite long careers at the institution, some non-DBER opinion leaders had not been promoted beyond associate professors. This may be because their current positions emphasized teaching and service, which are not as highly valued in their departments as research, as illustrated by this quote:

“In [my department] it’s publish or perish. You either publish and get grants or you do not get tenure. And if you have tenure, and this is the case of one person in the department, if you have tenure but you’re not able to publish or get a significant number of grants, you’ll never become a full professor. The chair won’t even put you up for it. But this person does more teaching than anyone else in that department.”

The most junior non-DBER opinion leader had a typical teaching load for research-active faculty. He had recently been promoted, on schedule, to associate professor and was perceived by colleagues to be both an accomplished researcher and teacher, as described by a colleague:

“Nathan is a great example; his recognition, he has been recognized as a very, very good teacher … I think what he has done in his innovation of teaching … is exemplary, and he embraced it as a young research-active assistant professor at the highest level.”

Whereas all four of the non-DBER opinion leaders were described as excellent teachers, this was only true for two of the five DBER opinion leaders. That does not mean that DBER faculty were not perceived as great teachers but that their most salient role in their departments was not as a teacher. DBER faculty were perceived as credible because their area of professional expertise was education while also being experts in their biology disciplines, as illustrated by the following quote:

“[Diana] had a lot of credibility because of her [biology discipline] background. She knows [her biology discipline] inside and out and she knows instruction, she knows the techniques and she obviously enjoys assessing and understanding how well it’s working.”

DBER faculty were also seen as innovative educators with knowledge of teaching strategies that other faculty lacked. They were perceived to be the resident education experts who were willing and able to provide resources for teaching and access to other education experts. They were commonly described as the person faculty would seek out if they were interested in changing their teaching, as illustrated by the following quotes:

“Because of her willingness to discuss learning techniques or teaching techniques with us, providing us new materials, introducing sort of, for example, like the Top Hat system for classroom engagement and bringing back information from workshops. She has been really influential and it is my idea of what an educator can be.”

“Darcy has been influential just because everybody knows and respects her as being an outstanding teacher and one of the first to bring the active learning. So if there’s any question, she’s one of the first people anybody would ask.”

In comparison with non-DBER opinion leaders, DBER faculty tended to be newer to their positions. One DBER faculty member was a full professor, two were associate professors, and two were assistant professors. The median number of years they had held positions in their departments was 7 yr (SD = 6). All DBER faculty had positions with research expectations, but they also had higher teaching EFT (equivalent full time) than other faculty in their departments, which means a greater percentage of their time was expected to be dedicated to teaching.

Change in Undergraduate Teaching

DBER and non-DBER opinion leaders were reported to contribute differently to changing teaching views and practices in the department. Although four non-DBER faculty were identified as opinion leaders using survey data, interview data did not confirm that these faculty influenced their colleagues to change their views and behaviors about teaching. Interview participants described only one of the four non-DBER faculty as prompting change. In contrast, interviewees described all five DBER opinion leaders as engendering change among departmental colleagues. Therefore, most of the following results pertain to DBER opinion leaders.

Our analysis revealed notable differences in the role and impact of opinion leaders across the Red, Yellow, and Green departments, so we present these results separately. Each section begins with one faculty member’s response to a question about what in his or her department helps him or her to be a good teacher. We selected these quotes to be representative of the most common ideas in each department and to introduce major themes observed for each department. At the end of this section, we summarize some potentially relevant differences in DBER positions among the three departments.

Yellow Department

Interviewer: What is going on in your department that might help you be a good teacher?

Interviewee: Well, I think the biggest thing that’s happened since I’ve gotten here is there has been an emphasis, I think university-wide, on bringing in science educators1 … I have a natural draw toward the science educators that are here … Since I came in as kind of an empty vessel as an instructor, the only baseline I had was the way I was instructed. Once I started interacting with Diana, and then went through the interview process and got to know Dakota … I started thinking about other ways that you could instruct. These people that I mentioned … were interested in teaching, instructing, using different methods other than lecturing. So I kind of got hooked into that way of instructing. I’m not there yet. I’m not as polished as I want to be, but especially considering where I am in my career, I’d really like to be able to say that by the time I retire, I could feel like I’m a really good instructor because I like doing it this way, I like interacting with the students, and I don’t particularly like standing up there and droning on and on and on, class after class.

The Yellow department had four opinion leaders according to survey data: two DBER and two non-DBER faculty. Both non-DBER opinion leaders were reputed to be dedicated educators who personally contributed substantially to undergraduate teaching in the department. However, neither non-DBER opinion leader was described by interviewees as prompting changes in colleagues’ views about teaching or teaching practices. The DBER opinion leaders were relatively new to the department, each having joined within the previous 3 yr, and each was perceived as having had a substantial impact on views about teaching in the department and the teaching practices of some of their colleagues.

The changes the DBER opinion leaders had engendered stemmed primarily from their roles as coordinators of a large course and through coteaching in that course with colleagues. The course they coordinated was the largest undergraduate course provided by the department, involving seven or more faculty per year, far more than any other single course. A small part of the DBER opinion leaders’ EFT was dedicated to the administration of this course. Before the arrival of the DBER opinion leaders, the course lacked explicit coordination, and faculty reported that the instructional quality had varied considerably. Course coordination completed by the DBER faculty included organizing meetings of course faculty to discuss common learning objectives and generally serving as a resource for instructors in the course. The DBER opinion leaders also designed and taught sections of the course that integrated evidence-based teaching strategies, freely shared all of their materials, and welcomed colleagues to observe their classes.

Faculty teaching in the coordinated course were encouraged, but not required, to be involved in identifying common goals and teaching strategies for the course. Colleagues appreciated that DBER faculty were welcoming, but not pushy. The general perception in the department was that no one should be forced to change his or her teaching but that support would be available to interested instructors. Some instructors of the coordinated course chose to collaborate with one another and others declined to do so, as described here:

“I think [Dakota’s] had to tiptoe around some people’s egos about how to instruct the course. I think there was a split in the instructors among just kind of ‘leave me alone’ and ‘I’m going to do my thing’ to the instructors that would attend meetings and get involved in unifying the material and some of the decisions about the way the course runs and kind of get on the same page. So I have attended those meetings, and Dakota has tried to develop kind of a unified curriculum.”

Collaborating with DBER opinion leaders prompted some faculty to critically examine their teaching practices. One interviewee reported that DBER faculty brought teaching to the spotlight in the department, making some faculty realize that “maybe we aren’t doing it as wonderfully well as we think we are.” Another interviewee described the impact of DBER faculty this way:

“I think now it’s different. I think there’s discussion about how you present the material … Faculty members get all grumpy, because you’ve got to have more content and the [DBER faculty] are saying, ‘Well, yeah but you got to have—you’ve got to teach it right.’”

Faculty in the Yellow department reported that coteaching with DBER opinion leaders had led some faculty to change their teaching practices. Commonly, when two science faculty members teach in the same section of the same course, they teach mostly independently, one after the other. Coordination is often limited to dividing up topics to cover and agreeing how grades will be calculated. Faculty who had cotaught with DBER opinion leaders reported having a much different experience. They described working closely with their DBER coteachers on both the content and teaching strategies used in the course. Coteachers regularly attended one another’s classes to observe and to help facilitate group work. Generally, this was the non-DBER faculty member’s first exposure to interactive strategies implemented in large courses, and the DBER opinion leader provided class structure and guidance to facilitate the success of these strategies. Interview respondents noted substantial changes in their colleagues’ teaching as a result of coteaching with DBER faculty, as described by this interviewee:

“I am really amazed that some of my colleagues whose teaching has been, like, radically transformed. I’m so surprised that they are, instead of just standing there lecturing, they are willing to break things up into small groups and wander around and kind of lose control of the classroom temporarily while the students do their own thing … So they’ll coteach something with Diana or with Dakota and suddenly they’ve been tossed out of this comfort zone they’ve been in for so many years and I have been really proud that now they are flexible enough to give it a shot … I know I have talked to a couple of them who said, ‘You know, I’m really enjoying this.’”

In addition to working with colleagues on teaching, the DBER opinion leaders in the Yellow department had collaborated on education components of grants for external funding.

Collaborating with DBER faculty on proposals made some faculty more aware of education as an area of scholarship. The following quote describes how a faculty member more seriously considers the education components of his grants after his experience working with a DBER colleague:

“So, Diana recently has had a big impact in figuring out how to more effectively include educational opportunities in my research program. Seeing her commitment to evaluating how well an outreach activity—what impact it’s having on education—has kind of stepped up my commitment to taking that seriously.”

The addition of DBER faculty has prompted substantial instructional reform among some faculty in the Yellow department, but this was mostly limited to faculty with whom DBERs have cotaught. Some faculty in the coordinated course have opted not to collaborate with their peers and have likely continued to teach primarily using lectures. Additionally, an instructor who does not teach the coordinated course reported that support for teaching is still lacking in the department:

“I know [support in the coordinated course] really changed a lot when Diana and Dakota came in … But that hasn’t really filtered into our course at all. So I would just say the resources [for teaching] I mean it’s basically been a peer thing where if you have questions, you go talk to somebody who’s been teaching for a long time and you get sort of personal advice and maybe a syllabus or something … But as far as really formal sessions where people get together and compare notes and things like that, that’s just never been part of the department so far.”

Red Department

Interviewer: What might be going on in your department that helps you be a good teacher in general?

Interviewee: There is a reasonably strong emphasis on—they don’t ask us to do a whole lot of teaching, but I think the expectation then is for what little they ask us to do we ought to do it well. The general ethos of being aware that there is kind of a body of literature on how to teach well is useful. So partly, just because we are aware of it; partly because I feel like if I try and do something that might … not work the first time I try it, that I will be supported in that, because everyone else—enough of the department is aware of what I am trying to do and why I would try to do it that way. And then just having that network of people who are also trying to do this; some of whom who have been doing it for a long time; some of whom who have been teaching for a long time but are still relatively new to, are trying to change how they teach. So I have senior faculty who are trying to incorporate these active-learning strategies and they are as new in it as I am, but then I have got folks like Dawn and Darcy who are pretty [much] masters at it, so its useful to have that. It has been very helpful.

The Red department had three opinion leaders: two DBER and one non-DBER faculty, and all three were reported to have engendered change in the department. Interviewees most often described the role of the opinion leaders as contributing to the growth and maintenance of a culture that values undergraduate teaching, as illustrated by the following quote:

“I think the culture here is that we talk about [teaching], and we have people like Dawn and Darcy in our department, who actually, I think they educate the professors here in terms of how students learn. So in general, we just have this sort of atmosphere that people do talk about teaching. People do think it’s important. I think the value is sometimes it’s—that the community or the society sort of impose on people.”

The idea that particular viewpoints about teaching may be “imposed” on members of the Red department is consistent with this department’s high transitivity (Table 4). Ideas are reinforced by high transitivity, because actors receive information directly and indirectly. For example, in a two-legged triad (Figure 1), actor B can only receive information directly from actor A, whereas in a transitive triad, actor B is also connected to actor C and can therefore receive the same information indirectly through actor C. If actor A is an opinion leader promoting evidence-based teaching strategies, then actor B will be more likely to be exposed to these strategies through multiple channels in the Red department compared with other departments. Change may therefore spread more efficiently in the Red department. The perception that the Red department has a culture that is uniquely supportive of undergraduate teaching is corroborated by the fact that the Red department had the densest departmental network and survey respondents in this department reported interacting with a greater percentage of their colleagues about teaching (Table 4).

Opinion leaders in the Red department had invested considerable time in providing training and mentoring on teaching for their colleagues, and these experiences had convinced interviewees that teaching was valued in the department. Many faculty in the Red department participated in Regional Teaching PD, in which the DBER opinion leaders had leadership roles. The department head strongly encouraged faculty to participate, which communicated that learning to teach well was an expectation in the department. Participation in a shared training experience was perceived to contribute to the culture of valuing teaching, as described here:

“I think probably half of our faculty has gone through the [Regional Teaching PD]. So there is a certain kind of critical mass effect that happens, I think, once the majority of people have been exposed to a certain way of thinking. It means you can talk to other people in that language.”

Faculty from other departments could also participate in Regional Teaching PD, but it was much less common. The Red department head advocated for faculty to participate, while the other department heads did not. It may be that the Red department head especially valued Regional Teaching PD because it was run by a DBER faculty member from the Red department.

The non-DBER opinion leader also provided mentoring that convinced colleagues teaching was valued. In fact, in more than one case, he had observed a colleagues’ class for most or all of a semester. The feedback he gave was formative and constructive in nature, rather than evaluative, shaping colleagues’ teaching, as one faculty member explained,

“So for example, I mean, you’ve probably heard many stories about Nicholas, but the first time I was teaching [introductory biology] was just a panic for me, because I’d never done that material and never done that size class, and Nicholas’ office is literally right next to mine. I didn’t ask him to do it and he didn’t tell me he was formally doing it, but for the weeks before hand and for the time I was teaching, I was here every day, every night, focusing on that, he would be here. And so I would constantly run over and then he’d get me three papers and I’d come back, and he’d give me this and I knew he was making himself available … I don’t know what we’ll do when he is not available to help with that.”

One interviewee had so valued the mentorship she received from this opinion leader that she had gone on to provide similar mentorship for another colleague, thus perpetuating actions that promoted quality teaching in the department.

Red department opinion leaders also contributed to a culture of valuing teaching by raising awareness about education research. They invited education experts to present at weekly departmental seminars, which were widely attended by departmental faculty. They had also presented their own education research to colleagues in regularly scheduled departmental gatherings, such as annual retreats. The current department head facilitated this by inviting the DBER faculty to present. Some interview participants indicated they would be unlikely to seek such experiences on their own, as illustrated by this quote:

“So, I think it was very interesting when we had, for example, a retreat. I recall maybe two or three years ago Dawn gave a very, very interesting talk about her research with the undergrads. We felt very, very intrigued to hear that. I mean typically, I will never go and hear those kinds of talks. But … I thought it was great.”

By providing opportunities to think and learn about teaching in standard departmental venues, the opinion leaders may have influenced colleagues who were unlikely to be influenced by efforts external to the department. The opinion leaders were also regularly vocal in department meetings about needing to provide quality undergraduate education, as illustrated in this quote:

“So, part of the role of people like Nicholas in the past has been to remind us of the importance of teaching and make sure it doesn’t get forgotten.”

Exposure to education research and to professional development that emphasized a scientific approach to teaching influenced how faculty in the Red department thought about teaching. Specifically, many faculty shared the perception that teaching should be informed by education research. Some interviewees even reported that there is an understood expectation in the department that faculty will approach their teaching scientifically, as described in this quote:

“And I also feel like, partly because of Darcy and Dawn’s presence that has helped, and still does.”, if you are going to teach, you should do it well, and you should think scientifically about how to do it well.”

Only a few interviewees in the Red department reported that they had changed their teaching practice as a direct result of interacting with opinion leaders. However, the culture of valuing both teaching and education research had encouraged several faculty to incorporate recommended strategies in their teaching. The following quote emphasizes that changes in teaching practice may only occur after multiple encounters with a new strategy:

“I didn’t adopt using student response systems in the large class until I had actually seen Darcy do a presentation at one of our faculty retreats and then I had seen another presentation and then I had gone to [Regional Teaching PD]. So I actually was exposed to it multiple times through the department before I finally made the leap. So having those resources where they can kind of keep you up-to-date, knowing there are any number of people here that I could have a conversation with about it, as I said we are bringing in speakers, so sort of having that support network.”

Green Department

Interviewer: What might be going on your department that helps you be a good teacher?