Abstract

Background:

Professionalism is integral to medical training and practice. Recent studies suggest generational differences in perceptions of professionalism, which have not been adequately explored in academic neurology.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was performed to describe perceptions of professionalism among representative physicians across the academic training spectrum of neurology. A self-report questionnaire adapted from a published instrument was distributed to students, residents, fellows, and faculty in neurology at a single institution. Responders rated 4 domains of professionalism: Personal Characteristics, Interactions with Patients, Social Responsibility, and Interactions with the Health Care Team (5-point Likert scale, not at all important to very important), and selected the “top 2” characteristics critical to professional behavior in each domain.

Results:

A total of 296 of 312 (95%) responded, including 228 students, 24 residents, 19 fellows, and 25 faculty. Respondents ranked the following components to be important/very important contributors to the expression of professional behavior: Personal Characteristics (98%, mean rating 4.6 ± 0.3), Interactions with Patients (97%, 4.6 ± 0.4), and Interactions with the Health Care Team (96%, 4.6 ± 0.5). Although mean ratings were high for Social Responsibility (4.3 ± 0.6), only 82% indicated that this was important/very important in the expression of professionalism, with a gradual decline from students (4.4 ± 0.6) to residents (3.99 ± 0.8, p = 0.02). The “top 2” contributors to each domain were similar across responders.

Conclusions:

Professionalism was perceived as critically important across the academic training spectrum in neurology, and the view regarding the top contributors to the expression of professionalism remained consistent among the respondents.

Professionalism, as defined by Epstein and Hundert, is “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community.”1 It is an integral component of medical practice and a core competency in graduate medical training.2 In the wake of recent publications citing changes in perceptions of professionalism,3,4 the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) called for policy changes to address and define professionalism in the modern era, highlighting its current importance.

Although the basic tenets of professionalism are common across professions both in and outside of medicine, the manner in which these core values are expressed is dependent on numerous factors, including sex,5 institution,5 age,6 culture,5 and generation.7,8 A study in psychiatry comprehensively identified 4 domains of what constitutes modern professionalism, including personal characteristics, interactions with patients, social responsibility, and interactions with the health care team.9 Authors reported that contributors to professional conduct differed between medical students, residents, and attending psychiatrists, suggesting that the perceptions of professionalism may differ by generation.9

None would argue that professionalism is not equally critical in neurology; however, few studies have described the language of modern professionalism across the stages of medical practice (i.e., medical student training, postgraduate training, and practice) in an academic neurology environment. Here, we describe a cross-sectional study examining professionalism as a physician across students, residents, fellows, and faculty in academic neurology.

METHODS

Study design

A cross-sectional study was designed consisting of medical students, residents, clinical fellows, and faculty physicians in the department of neurology at a single academic institution. A previously published questionnaire used for assessing attitudes toward professionalism in psychiatry was adapted with permission and distributed to all study participants using our institutional electronic evaluation system.9 All medical students rotating through the required 4-week neurology core clerkship completed the survey as a part of orientation. In addition, the survey was distributed to all postgraduate year (PGY) 2–4 adult neurology residents, PGY 3–5 pediatric neurology residents, clinical neurology fellows, and active clinical teaching faculty who work consistently with students and trainees in the department of neurology. Responses were collected and deidentified for analysis.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Approval was obtained from the institutional ethical standards committee for this study.

Survey instrument

The survey consisted of demographic questions on level of training, age (categorized in 5-year increments), sex, ethnicity, and year of medical school graduation and fellowship type (when applicable). Using the previously published instrument, questions pertaining to professionalism were divided into 4 components, as previously described: (1) Personal Characteristics (e.g., internal motivation, punctuality), (2) Interactions with Patients (e.g., respect for patients, maintaining confidentiality), (3) Social Responsibility (e.g., treating the underprivileged), and (4) Interactions with the Health Care Team (2 items: respect toward health care team, reporting dishonesty).9 In each section, respondents were asked to rate the importance of each individual factor as a contributor to the expression of professional behavior (5-point Likert scale: not at all important, somewhat important, neutral, important, and very important). In addition, respondents then selected the 2 characteristics they considered to be the most important (“top 2”). The final questions required respondents to rate the importance of 6 additional factors in the expression of professional behaviors, as described previously (5-point Likert scale, not at all important to very important).9

Data analysis

Data were collected electronically and deidentified. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata/SE v14 (Stata Corp, 2014). Missing values were rare: 1 student completed only the demographic questions and a second did not indicate the “top 2” Personal Characteristics. These missing data were excluded from analysis of professionalism. Data were analyzed as previously described, averaging across factors within each of the 4 domains.9 Internal consistency between items within the Personal Characteristics, Interactions with Patients, and Social Responsibility domains was determined by Cronbach α. Descriptive statistics were performed to determine means, SDs, medians, and ranges of responses to each item in the questionnaire and for each of the 4 major domains. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare responses by level of training, with pairwise comparison by the Bonferroni method when applicable. Likert responses were also divided binarily into important (i.e., “very important” or “important”) and less important (i.e., “neutral,” “somewhat important,” and “not at all important”). Logistic regression analysis was performed controlling for age, sex, and ethnicity. For each of the “top 2” characteristics, proportions were calculated and compared by ANOVA.

RESULTS

A total of 296 of 312 (95%) responded to the survey: 228 medical students (99% of 230 surveyed), 24 residents (86% of 28), 19 fellows (68% of 28), and 25 faculty (93% of 27). Age, sex, and ethnicity are reported in table 1; demographics by responder type are reported in table e-1 at Neurology.org/cp.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 296 participants in this cross-sectional study

Psychometrics and reliability

Items were internally consistent for each of the domains of professionalism, including Personal Characteristics (Cronbach α: 0.87), Interactions with Patients (0.79), and Social Responsibility (0.86). Despite the previous report stating that the item Managing Conflicts of Interest may not relate to the category of Social Responsibility,9 in the current study it was closely related to the other items in this domain and included in this analysis. The internal consistency of the items in the Interactions with Patients domain was acceptable (0.79) but slightly lower than that previously reported (0.85). When the item Placing Patient's Concerns Before Your Own was removed from this 5-item group, the consistency improved to an acceptable range (0.84); however, analysis with and without this item did not significantly differ, and in order to allow comparison with prior published results this item was included in the final analysis.

Major findings

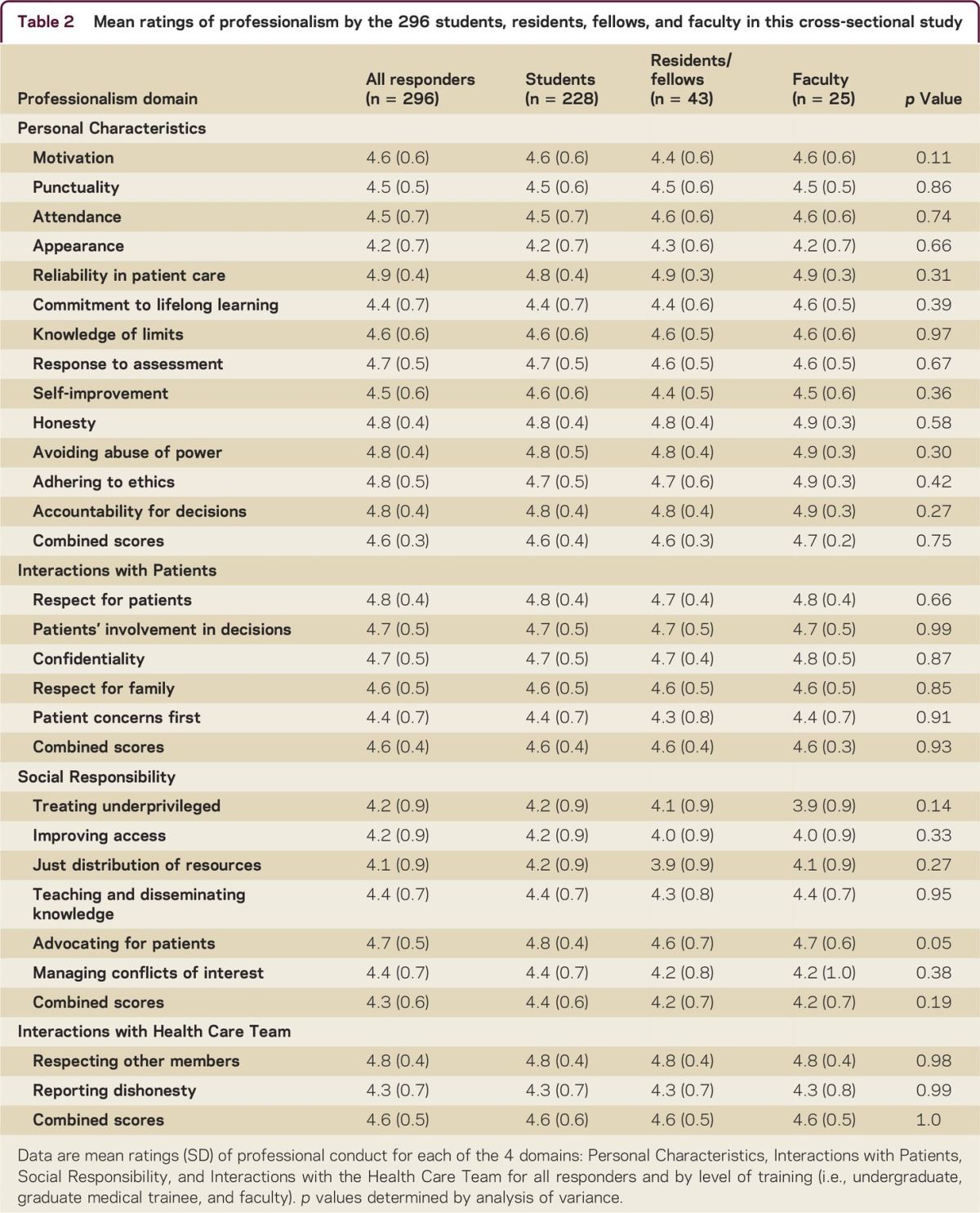

Overall, all responders (i.e., medical students, residents/fellows, and faculty) indicated that each of the 4 major domains (i.e., Personal Characteristics, Interactions with Patients, Social Responsibility, and Interactions with the Health Care Team) strongly contributed to the expression of professional behavior, with mean ratings of 4.6 ± 0.3 for Personal Characteristics, 4.6 ± 0.4 for Interactions with Patients, 4.3 ± 0.6 for Social Responsibility, and 4.6 ± 0.5 for Interactions with the Health Care Team (table 2). High mean ratings were observed for each of the individual questions that made up these total domain scores, and ratings from undergraduates, graduate medical trainees, and faculty were similar (table 1). There were no differences in the mean ratings for these 4 domains by age category (all p > 0.57), sex (all p > 0.19), or ethnicity (all p > 0.09). The percent indicating that these domains were important or very important to professional behavior was high for Personal Characteristics (98%), Interactions with Patients (97%), and Interactions with the Health Care Team (96%) but lower for Social Responsibility. Only 82% indicated that Social Responsibility was important or very important, with 15% indicating neutral importance and 3% indicating it to be only somewhat important. This relative decline was most evident for the items Treating the Underprivileged (18% ≤ neutral), Improving Access to Health Care (19% ≤ neutral), and Promoting Just Distribution of Resources (20% ≤ neutral) but not Advocating for Patients (1% ≤ neutral), Commitment to Teaching (9% ≤ neutral), and Managing Conflicts of Interest (8.5% ≤ neutral). When controlling for age, sex, and ethnicity, these findings were not significantly changed.

Table 2.

Mean ratings of professionalism by the 296 students, residents, fellows, and faculty in this cross-sectional study

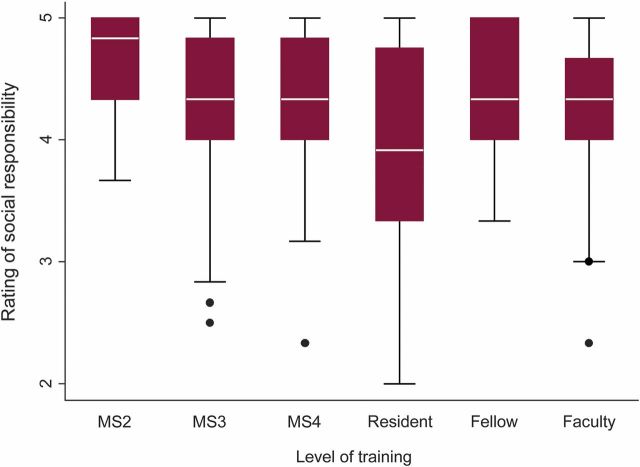

The mean ratings for each of the 4 major domains of professionalism did not differ when residents and fellows were considered together (i.e., undergraduate vs graduate medical trainee vs faculty). However, when residents and fellows were considered separately (i.e., medical student vs resident vs fellow vs faculty), significant differences in the mean rating of Social Responsibility were observed (table 3). Pairwise comparison of overall ratings for the Social Responsibility domain revealed that mean resident ratings (3.99 ± 0.8) were significantly lower than mean medical student ratings (4.4 ± 0.6, figure). This relative decline in mean ratings was gradual by year of schooling, with ratings of 4.6 ± 0.5 in second-year students, 4.4 ± 0.6 in third-year students, and 4.3 ± 0.5 in fourth-year students. Mean ratings then rose numerically in fellows, although this difference was not significant (4.5 ± 0.5, p = 0.065).

Table 3.

Assessment of differences in perceptions of professionalism across the stages of training in this cross-sectional study

Figure. Rating of social responsibility by level of training in this cross-sectional study.

Box plots of ratings of social responsibility by 5-point Likert scale (not important = 1, somewhat important = 2, neutral = 3, important = 4, and very important = 5) by level of training showing a gradual decline in ratings for second-year (MS2) (4.6 ± 0.5), third-year (MS3) (4.3 ± 0.6), and fourth-year medical students (MS4) (4.3 ± 0.6), residents (3.9 ± 0.8), fellows (4.5 ± 0.5), and faculty (4.3 ± 0.7, overall p = 0.04).

When responses were analyzed by the proportion of responders who indicated that each factor was important or very important (by 5-point Likert scale), at least 80% of students, fellows, and faculty indicated that Social Responsibility was an important or very important feature of professionalism. In contrast, only 50% of residents indicated similarly (p = 0.005), with 46% indicating neutral importance and 4% considering it to be only somewhat important (table 3). Of the individual factors contributing to the Social Responsibility domain, this difference in rating for residents was most evident for Treating the Underprivileged (p = 0.007), Improving Access to Health Care (p = 0.045), and Promoting Just Distribution of Resources (p = 0.005) but not Advocating for Patients (p = 0.07), Commitment to Teaching (p = 0.36), and Managing Conflicts of Interest (p = 0.33).

The “top 2” contributors to professional behavior were highly conserved across responders by stage of training (i.e., undergraduate vs graduate medical trainee vs faculty) for each of the major domains of professionalism (table 4). Reliability and accountability were the “top 2” Personal Characteristics for medical students, residents, and fellows. On average, faculty selected accountability and honesty as the “top 2” Personal Characteristics, with adherence to ethics and reliability being third and fourth most important, respectively. Faculty responses tended to cluster somewhat more on these common factors, although no statistical difference was observed and all groups agreed on the top 4. The “top 2” factors for the Interactions with Patients and Social Responsibility domains were the same for medical students, residents and fellows, and faculty. When residents and fellows were considered independently, there was no decline in the “top 2” factors for residents for any of the Social Responsibility items. In fact, 88% of residents indicated that patient advocacy was a top contributor to professionalism. Of note, faculty were less likely to select the item Maintaining Confidentiality (p = 0.003).

Table 4.

“Top 2” contributors to professional behavior by stage of training for the participants in this cross-sectional study

The majority of participants reported that Direct Observation and Modeling Behaviors (94%) and Individual Mentoring (94%) were important or very important factors in the formulation of professional behavior. In contrast, fewer responders reported that Formal Ceremonies (40%), Awarding Those Who Demonstrate Professionalism (53%), and Formal Curricular Activities (e.g., lectures, small groups) (54%) were important or very important characteristics of professionalism. Although no differences in reporting were observed for these 5 items by stage of practice, the importance of Including Assessment of Professional Behavior in the Evaluation Process did differ. For this item, 92% of faculty, 79% of residents and fellows, and 63% of students indicated that this was important or very important in formulating professional behavior (p = 0.003). This finding was recapitulated when comparing differences in mean rating of this item by age, such that a gradual increase was observed from <25 years (2.7 ± 0.6) to 26–30 years (3.7 ± 1.1), 31–35 years (3.9 ± 1.0), 36–40 years (4.5 ± 0.7), and >40 years (4.6 ± 0.5, total p < 0.009).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that despite varying stages of practice, health care professionals across the academic training spectrum rate perceived contributors to professionalism highly and in general place similar emphasis on personal characteristics, interactions with patients, and interactions with the health care team. We did observe some consistent differences in the rank prioritization of certain items of social responsibility, including treating the underprivileged, improving access to health care, and promoting just distribution of resources, in which residents rated these items lower than students and fellows did. However, the “top 2” contributors to professional behavior were highly consistent across responders for all domains, including social responsibility. Consistent with prior reports, we found that individual mentoring and modeling of professionalism to trainees were critical factors used to develop professional behavior but that differences exist in the perceived importance of assessing professionalism during training.10

The recent conversation around professionalism has been reinvigorated by calls from the AAMC to address an apparent rise in reporting of student mistreatment on the national Graduation Questionnaire (GQ).3,4 In a review of data compiled from the 2000–2011 GQs, the authors outline important steps in addressing student mistreatment, calling for redefining its inclusion in the teaching and assessment of professionalism.4 They acknowledged the challenges of this effort, specifically in establishing a universal definition of mistreatment and taking into account the effect of local professional culture and the need for a common language for describing professional conduct across generations.4 They also called for policies to promote cultural change in academic institutions.11 However, before such policies can be generated or change initiated, we must address the concern that perceptions of professional conduct may differ by generation and stage of practice.

A number of studies have addressed potential differences in attitudes toward professionalism in modern learners. In 1 study evaluating the effect of Facebook on perceptions of professionalism, 45% of students and only 17% of senior faculty considered what happens on social media separate from their professional practice.6 Despite this, more than 75% of students and only 33% of senior faculty thought that their professional integrity could be compromised by using Facebook.6 These results underscore the importance of rigorous evaluation of the generational differences in defining professional conduct in medicine.

We show that in an academic neurology setting, perceived contributors to professionalism were rated similarly for students, trainees, and faculty, who all rated personal, peer, and patient contributors to professionalism highly. The top contributors to professional behavior in each of these domains were also consistent despite differing ages, eras of training, generations, and educational curricula. Although these findings are different from those reported in the prior study in psychiatry, similarly high ratings (generally >4 on the same 5-point Likert scale) were observed.9 Aside from being conducted in a different specialty, our study included second- and fourth-year students as well as fellows, all of which could account for the differences.9 Our response rate was quite high, with 95% of those surveyed responding. In addition, the inclusion of the “top 2” contributors to professionalism provides important perspective, allowing for additional interpretation of the clinical relevance of small statistical differences in mean ratings. In our study, personal character traits including reliability, accountability, honesty, and adherence to ethics were highly valued by all responders. In contrast, external reflections of behavior including appearance, punctuality, attendance, and other outward indicators were relatively less valued. Of the many interactions health care providers have with patients and society, individual actions including respect for and advocating on behalf of one's patient were especially valued. Although all factors were rated highly, somewhat less emphasis was placed on communal and societal factors. Of interest, this study was performed before resurgence in social discussions around racially biased policing and discrimination in our region. Whether this would affect perceptions of social responsibility now is unclear. The results observed may reflect the emphasis on the doctor-patient relationship, its intimacy, and the call to care for the patient as an individual.

Despite the overwhelming consistency of responses across the phases of training for most of the domains, we did observe differences in the rank prioritization of social responsibility that may be important. A gradual decline in ratings of treating the underprivileged, improving access to health care, and promoting just distribution of resources was observed as medical students proceeded from second to fourth year, with a nadir in residency. This relative decline has been observed in other studies of resident perceptions of health advocacy and may reflect long hours, loss of control over personal schedules, physician burnout, or increased stress.12 Modern restrictions on resident duty hours have been shown to negatively affect aspects of professionalism, with faculty expressing concerns over less patient ownership and resident work ethic.13 The “hidden curriculum” and physician burnout have also been shown to erode professionalism and empathy.14–17 We did observe a strong emphasis placed on individual mentoring and modeling of behaviors as critical in professional development. Social media, texting, and other Web-based methods of networking are changing the language with which the next generations communicate and conduct their professional practice. Although methods may change over generations, our data suggest that the language of professional conduct remains the same.

Whether the tendency toward lower ratings of social responsibility by residents is in fact a reflection of a true decline in social professionalism or simply a feature of resident training itself is unclear. Postgraduate medical training focuses on the personal development of the resident and may shift focus away from societal responsibility. The “top 2” contributors to Social Responsibility were highly consistent across the levels of training and were the same for residents as for students and faculty, with more than 85% of residents indicating that patient advocacy was a critical factor. Thus, while the difference in mean ratings may reflect a true difference in attitudes toward professionalism during this phase of training, it may also be the case that the value of social professionalism remains high and that this difference reflects a shift in the focus of residency training on personal development.

Attitudes toward assessing professional behavior did differ by stage of practice. Whereas just over half of medical students indicated that assessment of professionalism was important in their development of professional behaviors, the overwhelming majority of faculty emphasized this. A similar result was observed by age. Although attitudes about contributors to professional behavior may not necessarily reflect conduct, this finding is important as the AAMC standardizes the assessment of professionalism and student mistreatment. At our institution, we have witnessed some conflict between students and faculty over assessing professional skills as our educators grapple with the need to evaluate this important domain despite student concerns over its equivalence to grading knowledge and skills. As educators and administrators review best practices for professionalism curricula and incorporate assessment of professional conduct,8 early engagement with students reiterating its importance and the reasoning behind its incorporation into student assessment will be critical to address these different attitudes and allay anxiety and frustration surrounding assessment of this critical aspect of the medical profession.

This study, while strengthened by the use of a previously studied instrument, assesses only the aspects of perceived contributors to professionalism incorporated into this survey and does not represent a comprehensive review of all aspects of professionalism. This survey assessed perceptions of professionalism and not professional conduct (i.e., professional acts). Likert scales, such as those used in this survey, are subject to social desirability bias, or the tendency of survey respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others, which could account for the differences in Social Responsibility and the lack of differences in the other domains. The findings in this study are limited to an academic neurology setting and may not generalize to nonacademic environments or other specialties. Nonphysicians, including nurses, ancillary staff, health care administrators, and patients, were not included in this study. Perceptions of professional conduct from these important stakeholders in modern medical practice may also be informative in developing a comprehensive language of modern professionalism and further exploring perceptions of social responsibility. In the current study, responders were categorized by stage of practice and category of age, which provided a means of assessing differences in perception of professionalism by these important indicators; however, a strict generational definition was not used.

In conclusion, we show in a group of students, residents, fellows, and faculty in neurology that contributors to professional behavior are highly valued and remain consistent across the academic training spectrum. These data show that students, trainees, and clinical educators share a language of professional conduct. Mentoring, role modeling, and exemplifying professionalism are critical in promoting the development of optimal professional behaviors for the next generation of clinicians.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the substantial contributions of Dr. Justin McArthur and Ms. Paula David, whose efforts and assistance were paramount in achieving the high level of departmental participation in this study. The authors also thank Dr. Mary K. Morreale for the generous counsel, advice, and permission to use the survey instrument employed in this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/cp

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Strowd contributed to the study design, analysis, and drafting the manuscript. Dr. Saylor contributed to the study design, analysis, and drafting the manuscript. Dr. Salas contributed to the study design, analysis, and drafting the manuscript. Dr. Thorpe contributed to the study design and drafting the manuscript. Ms. Cruz contributed to the study design and drafting the manuscript. Dr. Gamaldo contributed to the study design, analysis, and drafting the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

R.E. Strowd has received grant funding from the American Academy of Neurology to support fellowship training and serves as Deputy Editor of the Resident & Fellow Section of Neurology. D. Saylor has received funding for travel or speaker honoraria from the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infection and the American Academy of Neurology and receives research support from NIH (NINDS/NIMH), Johns Hopkins Global Health Center, Sara's Wish Foundation, and World Federation of Neurology Grants-in-Aid. R. M. E. Salas receives research support from the NIH, Johns Hopkins University, American Sleep Medicine Foundation, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. R. Thorpe serves on the editorial boards of Ethnicity and Disease, Ethnicity and Health, and Behavioral Medicine. T.E. Cruz and C.E. Gamaldo report no disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein R, Hundert E. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002;287:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltier WL. Core competencies in neurology resident education: a review and tips for implementation. Neurologist 2004;10:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook AF, Arora VM, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad Med 2014;89:749–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mavis B, Sousa A, Lipscomb W, Rappley MD. Learning about medical student mistreatment from responses to the medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med 2014;89:705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagler A, Andolsek K, Rudd M, Sloane R, Musick D, Basnight L. The professionalism disconnect: do entering residents identify yet participate in unprofessional behaviors? BMC Med Educ 2014;14:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osman A, Wardle A, Caesar R. Online professionalism and Facebook—falling through the generation gap. Med Teach 2012;34:e549–e556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohr NM, Moreno-Walton L, Mills AM, Brunett PH, Promes SB; Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Aging and Generational Issues in Academic Emergency Medicine Task Force. Generational Influences in academic emergency medicine: teaching and learning, mentoring, and technology (part I). Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:190–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 25. Med Teach 2013;35:e1252–e1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morreale MK, Balon R, Arfken CL. Survey of the importance of professional behaviors among medical students, residents, and attending physicians. Acad Psychiatry 2011;35:191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students' perceptions of teaching. BMJ 2004;329:770–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med 2014;89:817–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafford S, Sedlak T, Fok MC, Wong RY. Evaluation of resident attitudes and self-reported competencies in health advocacy. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griner D, Menon RP, Kotwall CA, Clancy TV, Hope WW. The eighty-hour workweek: surgical attendings' perspectives. J Surg Educ 2010;67:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med 2011;86:996–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Billings ME, Lazarus ME, Wenrich M, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. The effect of the hidden curriculum on resident burnout and cynicism. J Grad Med Educ 2011;3:503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernat JL. Challenges to ethics and professionalism facing the contemporary neurologist. Neurology 2014;83:1285–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigsbee B, Bernat JL. Physician burnout: a neurologic crisis. Neurology 2014;83:2302–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]