Abstract

Understanding the molecular underpinnings of sensitivity to specific therapies will advance the goal of precision medicine in prostate cancer. We identified three patients with metastatic, castration resistant prostate cancer who achieved exceptional response to platinum chemotherapy (not frontline treatment for prostate cancer), despite disease progression on prior standard therapies. Using targeted next generation sequencing on primary and metastatic tumor, we found that all three patients had biallelic inactivation of BRCA2, a tumor suppressor gene critical for homologous DNA repair. Notably, two had germline BRCA2 mutations, including a patient without compelling family history who was diagnosed at age 66. The third patient had somatic BRCA2 homozygous copy loss. Biallelic BRCA2 inactivation in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer warrants further exploration as a predictive biomarker for sensitivity to platinum chemotherapy.

Keywords: BRCA2, platinum, carboplatin, prostate cancer, mCRPC, DNA repair

INTRODUCTION

Treatment for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) now includes taxanes, androgen receptor pathway inhibitors, active cellular therapy and a bone-targeting radiopharmaceutical1. Predictive biomarkers are needed to guide treatment selection and sequence. Reports describing the mutational landscape of mCRPC hold great promise for precision medicine, but actionable treatment decisions remain uncertain 2–4.

Platinum chemotherapy is infrequently used for prostate cancer except in cases of neuroendocrine differentiation5. We identified three patients with non-neuroendocrine mCRPC with exceptional response to platinum, defined as patients with advanced cancer who attain a complete or partial response lasting at least 6 months when expected response is 20% or less. To identify molecular changes associated with exceptional response, we retrospectively performed clinical targeted next generation sequencing on tumor DNA. Surprisingly, the common finding between all three was biallelic inactivation of the homologous recombination DNA repair gene, BRCA2.

RESULTS

Patient 1 was diagnosed at age 66 with PSA 24.8 ng/mL and Gleason 4+4 prostate adenocarcinoma and underwent neoadjuvant androgen deprivation (ADT) on a clinical study followed by radical prostatectomy and salvage radiotherapy. Four years later, he was found to have metastases to liver, lymph nodes and bone. Biopsy of liver metastases revealed adenocarcinoma without evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation.

He then received docetaxel with a PSA decline from 136 ng/mL to 59 ng/mL followed by PSA rise, and treatment with abiraterone followed by enzalutamide, both resulting in PSA and radiographic progression. Given earlier progression on docetaxel alone, he then received docetaxel and carboplatin with a PSA decline (Fig. 1A) and radiographic response (not shown). After a 6-month treatment holiday, he resumed docetaxel/carboplatin again with PSA decline. Unfortunately, he developed worsening malignant pleural effusions and ascites and ultimately elected to transition to hospice.

Figure 1.

Clinical treatment course and PSA response. A) Patient 1, B) Patient 2, C) Patient 3. Abbreviations: DOC=docetaxel, ABI=abiraterone, ENZ=enzalutamide, CAR=carboplatin, DOX=doxorubicin, CIS=cisplatin, ETO=etoposide, PAC=paclitaxel. Platinum chemotherapies are in bold red. Stars denote time of metastatic biopsies.

DNA sequencing of the metastatic liver biopsy revealed two BRCA2 mutations, p.Q3066X and an exon 11 partial deletion on separate alleles (Table 1).

Table 1.

BRCA2 mutations identified.

| BRCA2 mutations* | Mutation type | Germline | Primary | Metastases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | allele 1 | c.9196C>T; p.Q3066X | Premature stop | X | X | X |

|

|

||||||

| allele 2 | 127bp del in exon 11 | Frameshift deletion | X | X | ||

|

| ||||||

| Patient 2 | allele 1 | c.8904delC; p.V2969Cfs*7 | Frameshift deletion | X | X | X |

|

|

||||||

| allele 2 | c.2611delT; p.S871Qfs*3 | Frameshift deletion | ** | X | ||

|

| ||||||

| Patient 3 | allele 1 | Homozygous copy loss | Copy loss | X | X | |

|

|

||||||

| allele 2 | Homozygous copy loss | Copy loss | X | X | ||

Mutations are reported using reference transcript NM 000059.3

Low tumor purity limited detection of somatic mutations

Patient 1 did not have a significant family history of cancer despite clear evidence of an inherited deleterious BRCA2 mutation on germline testing. In light of these findings, he was referred to Medical Genetics and mutation was confirmed.

Patient 2 was diagnosed at age 53 with PSA 6.8 ng/mL and Gleason 5+4 prostate adenocarcinoma and underwent radical prostatectomy followed by salvage radiotherapy with ADT. Five years later, his PSA rose to 12.0 ng/mL and bone metastases were identified. He received 3 years of intermittent ADT. Upon developing castration resistance, he was treated with abiraterone and then enzalutamide, both resulted in transient control and then PSA rise (Fig. 1B) and progressive disease. He then received docetaxel with no response, followed by carboplatin/doxorubicin for 6 months with PSA and clinical response. Sequencing of a metastatic biopsy identified two deleterious BRCA2 frameshift mutations including one that was germline (Table 1).

Patient 2 had a family history suggestive of a high penetrance germline mutation with both father and paternal grandfather with prostate cancer and a paternal aunt with breast cancer. He was referred to Medical Genetics and mutation was confirmed.

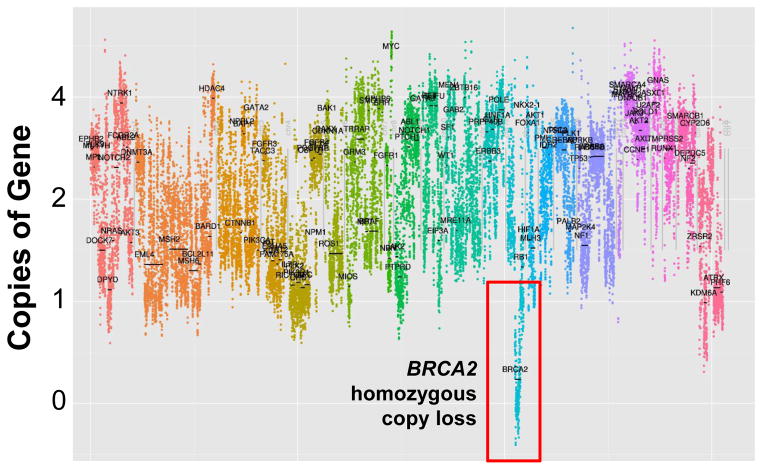

Patient 3 was diagnosed at age 70 with PSA 4.9 ng/mL, Gleason 5+5 prostate adenocarcinoma metastatic to pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. He developed castration resistance 6 months after initiating ADT and was found to have liver metastases when PSA reached 10.0 ng/mL. Metastatic liver biopsy was obtained to assess for neuroendocrine differentiation, which was ruled out with immunohistochemistry. He was treated with docetaxel/carboplatin with a near complete radiographic and PSA response (Fig. 1C). He was subsequently treated with abiraterone with disease progression and went on to receive a second course of docetaxel/carboplatin with another near complete radiographic and PSA response. He then received “maintenance” carboplatin for over two years of progression free survival. Sequencing of the previously obtained liver biopsy revealed somatic homozygous BRCA2 copy loss in the metastasis (Table 1). We were unable to confirm the presence of biallelic BRCA2 copy loss in the primary tumor due to insufficient tumor.

DISCUSSION

This case series documents three patients with mCRPC who achieved exceptional clinical response to platinum-based therapy after failure or progression on front-line therapies. Using a targeted next generation sequencing clinical assay, we identified that all three had biallelic BRCA2 inactivation in their tumors through either homozygous copy loss or germline deleterious mutation and somatic loss of function in the second allele in their metastases. By selecting for tumors with hypersensitivity to DNA damage induced by platinum chemotherapies, it is biologically plausible that defects in DNA repair would be revealed, particularly in light of observed platinum sensitivity in BRCA1/2 germline mutation carriers in other cancer types, notably ovarian and breast cancers6.

The prevalence of inactivation of BRCA2 and other DNA damage repair genes in mCRPC is higher than previously thought and will require further validation. In one report, 7/50 (14%) of lethal prostate cancers were found to have alterations in BRCA22. The whole exome sequencing results of the initial 150 mCRPC metastases from the SU2C Prostate International Dream Team demonstrated that 19% had aberrations in DNA repair genes (a combination of somatic and germline) including BRCA1, BRCA2 and ATM4.

Inheritance of deleterious BRCA2 mutations is well-established to increase the risk of developing prostate cancer in addition to breast, ovarian, pancreas and other malignancies. Male BRCA2 mutation carriers with localized prostate cancer are at substantially higher risk of dying from prostate cancer than their non-mutation carrying counterparts7. Together with the SU2C data, this suggests that biallelic inactivation (germline and somatic) of BRCA2 and related homologous recombination genes may be enriched among patients with aggressive mCRPC, especially when compared with the broader population of all (mostly indolent) prostate cancers.

Our case series provides evidence that homozygous inactivation of BRCA2 in mCRPC may confer sensitivity to platinum agents. Our series is limited by its small numbers and retrospective nature, but suggests that inactivation of BRCA2 and other DNA repair genes could be clinically useful as predictive biomarkers of platinum response. Whether other patients with hemizygous or homozygous inactivation of BRCA2 or those with inactivation of other DNA repair pathway genes will be sensitive to DNA damaging agents can only be addressed in prospective studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first report to associate dramatic response to platinum in men with mCRPC and unselected for a priori mutation carriage, with biallelic loss of BRCA2. Our report adds substantively to prior case reports that known BRCA2 mutation carriers with mCRPC may respond particularly well to platinum chemotherapies. This mirrors breast and ovarian cancers, where platinum chemotherapies are commonly used and evidence suggests that germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes such as BRCA2 are associated with response to platinum and overall survival8.

BRCA1/2 mutation carriers have also been effectively treated with PARP inhibitors, which render synthetic lethality in cells with defective homologous DNA repair. Dramatic responses to PARPi have been reported, most recently by Mateo, et al. Among men with metastatic prostate cancer no longer responding to standard therapies whose tumors had evidence of DNA repair defects (including BRCA2, ATM, Fanconi anemia genes and CHEK2), treatment with the PARP inhibitor olaparib resulted in a response rate of 88% (14/16)9. Clinical studies testing platinum agents, in combination and/or in sequence with PARPi, should also be explored for the subset of mCRPC patients whose tumors have biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 and related homologous recombination repair pathway genes.

In the context of emerging data that BRCA1/2 mutations may be present in up to 20% of mCRPC4 and that BRCA2 mutation-associated prostate cancers are more aggressive7, we are heartened by the dramatic platinum responses in these three patients whose tumors carried biallelic inactivation of BRCA2. Collectively, recent findings present a strong case for larger studies evaluating the tumors of all men who develop metastatic prostate cancer for biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 and related homologous DNA repair genes. These appear to be likely predictive biomarkers for treatment response to DNA-damaging therapy such as PARP inhibition and thewidely available platinum chemotherapies

METHODS

Patients

We identified 14 patients with mCRPC treated with docetaxel and carboplatin between 2010 and the present. Although there was no standard institutional approach to treating patients with docetaxel and carboplatin, none had evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation and most had aggressive features such as visceral involvement. Five of 14 patients (36%) achieved treatment response, defined as PSA decline by 50% or radiographic partial response. Three patients had tumors available for analysis, and are reported here. All three patients provided written, informed consent for review of their medical record and sequencing of their primary and/or metastatic prostate cancer tissue. Research was conducted with University of Washington IRB approval.

UW-OncoPlex testing

DNA was extracted from FFPE samples, as previously described10. H&E-stained slides were reviewed before DNA extraction for all FFPE samples, and when feasible, macrodissection of tumor areas was performed to enrich tumor cellularity. We performed sequencing with UW-OncoPlex, a validated, clinical molecular diagnostic assay that collects simultaneous deep-sequencing information, based on >500× average coverage, for all classes of mutations in 194 targeted, clinically relevant genes, as previously reported10. At the time of this writing, 31 patients with prostate cancer have undergone tumor sequencing with UW-OncoPlex at our institution. Four of 31 (13%) were identified to have biallelic BRCA2 inactivation, one of whom died before results became available and had not received platinum chemotherapy. The cases of the three others are reported here.

Figure 2.

Copy number variation plot for metastatic tumor from Patient 3. Changes in number of copies of genes within tumor cells were identified directly by OncoPlex sequencing. X-axis: left to right, each chromosome (1-22, x) is depicted in a different color. Y-axis: copies of genes. Selected genes are labeled.

CME Question.

In addition to the potential association of biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 with sensitivity of metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer to platinum chemotherapy reported in this case series, there is evidence in the literature to support the following statements:

When an inactivating BRCA2 mutation is identified in germline DNA, there may be an increased risk of prostate cancer in addition to breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancers.

There is a higher risk of prostate cancer-associated death among prostate cancer patients who are BRCA2 mutation carriers compared to non-carriers.

Recent data suggests that up to 20% of metastatic castration resistant prostate cancers may contain biallelic inactivation of DNA damage repair genes such as BRCA2.

All of the above.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING/SUPPORT

This study was supported by generous funding from the Institute for Prostate Cancer Research, the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer SPORE CA097186, Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Awards (to HHC and CCP), Congressional Designated Medical Research Program (CDMRP) award PC131820 (to CCP).

We are especially grateful to the patients who generously volunteered to participate in this study. In addition, we thank: Nola Klemfuss, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Bob Livingston, University of Washington; and Hiep Nguyen University of Washington, for their help with this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Montgomery had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design: Cheng, Pritchard, Nelson, Montgomery

Development of methodology: Pritchard

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Cheng, Pritchard, Boyd, Nelson, Montgomery

Drafting of the manuscript: Cheng, Pritchard, Nelson, Montgomery

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cheng, Pritchard, Boyd, Nelson, Montgomery

Statistical analysis: Cheng, Pritchard, Nelson, Montgomery

Obtained funding: Pritchard, Nelson, Montgomery

Administrative, technical or material support: Cheng, Pritchard, Boyd, Nelson, Montgomery

Study supervision: Cheng, Pritchard, Nelson, Montgomery

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Basch E, Loblaw DA, Oliver TK, et al. Systemic therapy in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer:American Society of Clinical Oncology and Cancer Care Ontario clinical practice guideline. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(30):3436–3448. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7406):239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltran H, Yelensky R, Frampton GM, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of advanced prostate cancer identifies potential therapeutic targets and disease heterogeneity. European urology. 2013;63(5):920–926. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161(5):1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltran H, Tomlins S, Aparicio A, et al. Aggressive variants of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20(11):2846–2850. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan DS, Rothermundt C, Thomas K, et al. “BRCAness” syndrome in ovarian cancer: a case-control study describing the clinical features and outcome of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(34):5530–5536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro E, Goh C, Leongamornlert D, et al. Effect of BRCA Mutations on Metastatic Relapse and Cause-specific Survival After Radical Treatment for Localised Prostate Cancer. European urology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott CL, Swisher EM, Kaufmann SH. Poly (adp-ribose) polymerase inhibitors: recent advances and future development. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(12):1397–1406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(18):1697–1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pritchard CC, Salipante SJ, Koehler K, et al. Validation and implementation of targeted capture and sequencing for the detection of actionable mutation, copy number variation, and gene rearrangement in clinical cancer specimens. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2014;16(1):56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]