Abstract

Background & Aims

Known Genetic factors explain only a small fraction of genetic variation in colorectal cancer (CRC). We conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to identify risk loci for CRC.

Methods

This discovery stage included 8027 cases and 22577 controls of East-Asian ancestry. Promising variants were evaluated in studies including as many as 11044 cases and 12047 controls. Tumor-adjacent normal tissues from 188 patients were analyzed to evaluate correlations of risk variants with expression levels of nearby genes. Potential functionality of risk variants were evaluated using public genomic and epigenomic databases.

Results

We identified 4 loci associated with CRC risk; P values for the most significant variant in each locus ranged from 3.92×10−8 to 1.24×10−12: 6p21.1 (rs4711689), 8q23.3 (rs2450115, rs6469656), 10q24.3 (rs4919687), and 12p13.3 (rs11064437). We also identified 2 risk variants at loci previously associated with CRC: 10q25.2 (rs10506868) and 20q13.3 (rs6061231). These risk variants, conferring an approximate 10%–18% increase in risk per allele, are located either inside or near protein-coding genes that include TFEB (lysosome biogenesis and autophagy), EIF3H (initiation of translation), CYP17A1 (steroidogenesis), SPSB2 (proteasome degradation), and RPS21 (ribosome biogenesis). Gene expression analyses showed a significant association (P <.05) for rs4711689 with TFEB, rs6469656 with EIF3H, rs11064437 with SPSB2, and rs6061231 with RPS21.

Conclusions

We identified susceptibility loci and genes associated with CRC risk, linking CRC predisposition to steroid hormone, protein synthesis and degradation, and autophagy pathways and providing added insight into the mechanism of CRC pathogenesis.

Keywords: Epidemiology, single nucleotide polymorphisms, colon cancer, eQTL

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most frequently diagnosed malignancies in the world, including most Asian countries.1 Genetic factors play an important role in the etiology of both familial and sporadic CRC.2 Through family-based studies, multiple CRC susceptibility genes have been identified, including APC, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, BMPR1A, SMAD4, POLE, POLD1, GREM1, NTHL1, LKB1/STK11 and MUTYH.3 Deleterious germline mutations in these genes, however, account for less than 5% of CRC cases in the population. It is believed that many common, low-penetrance genetic risk variants exist for CRC and, collectively, these variants explain a substantial proportion of genetic variation for CRC. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have become a powerful tool to uncover genetic susceptibility factors for complex diseases. To date, more than 40 CRC GWAS risk loci have been identified,4–21 which have expanded our understanding of the etiology of CRC. However, these common risk variants, along with known CRC susceptibility genes, explain only a small fraction of genetic variation for CRC.22

It has been demonstrated that GWAS conducted in non-European populations are valuable in identifying genetic variants for complex traits.8, 11 Because of different genetic architectures and environmental exposures, studies in non-European populations can often discover important genetic risk variants that are otherwise difficult to identify.8, 11 Furthermore, these studies can uncover risk variants specific to the study population. To search for new CRC susceptibility loci, we conducted a large, multi-staged genetic study including 19,071 cases and 34,624 controls of East Asian ancestry. To investigate the generalizability of our findings to other populations, we evaluated the newly-identified risk variants in16,984 cases and 18,262 controls of European ancestry.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This study was conducted as part of the Asia Colorectal Cancer Consortium (ACCC), including a total of 19,071 cases and 34,624 controls of East Asian ancestry from 14 studies conducted in China, South Korea and Japan (Supplementary Table 1). The details of these studies are described in the supplementary materials. Compared to our previous GWAS studies,8, 11 we expanded the discovery effort by including the Japan Biobank (BBJ) study (2,814 cases/11,358 controls) and three additional studies (3,519 cases/5,989 controls) genotyped with a customized exome array, the details of which are described in the genotyping section. Specifically, the discovery stage consisted of 8,027 cases and 22,577 controls, including 4,888 cases and 10,243 controls from six studies conducted among Chinese in Shanghai and Guangzhou, 2,814 cases and 11,358 controls from a study conducted among Japanese in Japan and 325 cases and 976 controls from a study conducted among Koreans in South Korea. Replication stage 1 consisted of 6,532 cases and 8,140 controls, including 677 cases and 1,114 controls conducted among Chinese in Guangzhou, 236 cases and 472 controls from a study conducted among Japanese in Japan and 5,619 cases and 6,554 controls from three studies conducted among Koreans in South Korea. Replication stage 2 included 4,512 cases and 3,907 controls from a study conducted among Chinese in Beijing. All study protocols were approved by the relevant institutional review boards and all study participants provided written informed consent.

The studies in European descendants comprised 16,984 cases and 18,262 controls recruited in North America, Europe and Australia, which are included in three consortia; the Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO), the Colorectal Transdisciplinary (CORECT) Study, and the Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR). The details of these studies have been described previously.10

Genotyping and imputation in the discovery stage

Genotyping and quality control (QC) for studies in the discovery stage have been described previously.8, 11 Briefly, genotyping for five of the eight studies included in the discovery stage were completed using Affymetrix or Illumina SNP arrays (Supplementary Table 2). In previous studies conducted in the ACCC, imputation was conducted using the CHB and JPT HapMap 2 panel as the reference.8, 11 To increase the coverage of genotypes in this study, we imputed genotypes for each of these five studies with data from the 1000 Genomes Project Phase I Release (Version 3) as the reference. Only SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 5% and a high imputation quality (R2 > 0.70) were included. After QC filtering, approximately 4 million genotyped or imputed SNPs on 22 autosomes remained for analysis. Genotyping for the remaining three studies included in the discovery stage was completed using Illumina Infinium assays with 59,317 variants as the customer add-on contents onto the Illumina HumanExome Beadchip. Of the 302,218 variants included in this array, 44,428 have an MAF of 5% or higher. We did not impute genotypes in these three studies given the low-density coverage of the genome by these common variants. After QC filtering, 40,647 SNPs with an MAF of 5% or higher remained for the analysis. Little evidence of substantial population stratification was found in any of the eight studies included in this stage (the inflation factor for each study was < 1.05).

SNP selection and genotyping in the replication stages

No apparent heterogeneity across the eight studies included in the discovery stage was noted, and thus a fixed-effects meta-analysis was performed to obtain the overall summary statistics for the association of genetic variants with CRC risk. We selected SNPs for further evaluation according to the following criteria: (i) P ≤ 0.0001 in the discovery stage; (ii) consistent direction of association across all eight studies included in the discovery stage (P for heterogeneity > 0.05), (iii) in no or moderate linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2 < 0.30 in East Asians) with any known CRC risk variant or SNPs that had been evaluated in our previous replication stages.8, 11 A total of 38 independent association signals were identified. For each signal, we selected the SNP with the most significant P-value for replication. Of these 38 SNPs, 36 were successfully genotyped and evaluated in an independent sample of 6,532 cases and 8,140 controls (replication stage 1). SNPs that showed evidence of association (one-sided P < 0.05) in replication stage 1 and in the same direction of the association as seen in the discovery stage were further evaluated in another independent sample of 4,512 cases and 3,907 controls (replication stage 2) (Supplementary Table 3).

Using the iPLEX Sequenom MassARRAY platform, genotyping for replication stage 1 and 2 studies was conducted at the Vanderbilt Molecular Epidemiology Laboratory and the Fudan-VARI Center for Genetic Epidemiology Core lab, respectively. Four negative controls (water) and eight positive quality controls (HapMap or duplicate samples) were included in each 384-well plate. We filtered out SNPs with (i) genotype call rate < 95%, (ii) genotyping concordance rate < 95% in positive control samples, (iii) an unclear genotype call or (iv) P for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium < 10−5 in controls. We calculated the mean concordance rate using data from positive quality control samples. The mean concordant rate was 99% with a median value of 100% in each of the five participating studies included in replication stage 1 and was 98% with a median value of 98% in the replication stage 2 study.

Genotyping of samples in GECCO, CORECT, and CCFR was conducted using Illumina and Affymetrix Arrays. The details of genotyping, QC and imputation have been reported previously.5, 10

Gene expression and protein abundance evaluation of candidate genes

The gene closest to each of the risk variants identified in this GWAS was selected for evaluation of its expression level in correlation with the risk variant in adjacent normal tissues from 188 CRC patients of East-Asian descent. The details of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis and quantitative western blotting are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis

Associations between SNPs and CRC risk were evaluated on the basis of the log-additive model using mach2dat,23 PLINK version 1.0.7,24 R version 3.0.2 (See URLs) and SAS version 9.4. Per-allele odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from logistic regression models, adjusting for age, sex and the first ten principal components when appropriate. Association analysis was conducted separately for each study. Because there was no apparent heterogeneity across participating studies, fixed-effects meta-analyses were used to obtain summary results for each stage and for all stages combined with the inverse-variance method using METAL.25 SNPs associated with CRC risk at P < 5×10−8 in the combined analysis were considered genome-wide significant. Stratified analyses were performed to assess whether the associations differ by tumor sites (colon or rectum), ethnicity (Chinese, Korean or Japanese) and sex (men or women). We estimated heterogeneity across studies and subgroups with Cochran’s Q test. We estimated haplotype frequencies with the expectation maximum algorithms in the Haplo. stat package (see URLs) in R (version 3.0.2) and conducted haplotype analyses when two or more SNPs were identified at the same locus.

Details of the eQTL analysis using data from East-Asian patients and the analysis of the SPSB2 isoform using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas project are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Bioinformatics analyses

To identify putative functional variants for newly identified loci, all variants in LD (r2 > 0.20) with the risk variant in each locus were identified using data from the 1000 Genomes Project (phase1 release v3.0). Non-coding variants were mapped to the 15 chromatin states across multiple normal colorectal mucosal tissues derived by the Roadmap Epigenomics (REMC) project 26 and to the epigenomic maps of histone markers (H3K4Me1, H3K4Me3, and H3K27Ac) across CRC cell lines derived by the Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) project.27 We focused on variants in promoters or enhancers. We identified the corresponding genes as the target genes for variants in promoters. We identified the interacting genes for variants in enhancers using data of enhancer- transcription start site (TSS) association from the Functional ANnoTation Of the Mammalian Genome 5 (FANTOM5) project, which evaluated correlations of the transcriptional activity of the enhancer and putative target genes. 28 Coding variants were evaluated using the SIFT29 and PolyPhen-2 algorithms.30 We proposed the most likely candidate gene at each locus according to the following criteria: 1) functional evidence; 2) distance to the risk variant; 3) results from eQTL analysis; 4) biologic functions and potential roles in cancer according to previous literature.

Results

Combined analyses of data from the discovery and replication stages revealed seven SNPs associated with CRC risk at the genome-wide significance level (P < 5×10−8), including rs4711689 at 6p21.1 (TFEB), rs4919687 at 10q24.3 (CYP17A1), rs11064437 at 12p13.3 (SPSB2), rs2450115 and rs6469656 at 8q23.3 (EIF3H), rs10506868 at 10q25.2 (VTI1A), and rs6061231 at 20q13.3 (RPS21) (Table 1). SNP rs10506868 at 10q25.2 was correlated with a risk variant (rs12241008, r2 = 0.60, D′ <1 in East Asians) identified in a recent GWAS study,7 and thus this locus was not further evaluated in the subsequent analysis of this study. Interestingly, rs10506868 is located in intron 6 of the VTI1A gene, a fusion partner of a CRC susceptibility candidate gene, TCF7L2, identified in our previous GWAS study.8

Table 1.

Summary results for newly identified genetic risk variants associated with colorectal cancer risk at P < 5.0 ×10−8 East-Asian descendants

| SNP | Locus | Genea | Positionb | Allelesc | EAFd | Discoverye | Replicatione | Combinede | Heterogeneity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,027 cases /22,577 controls | 11,044 cases/12,047controls | 19,071 cases /34,624 controls | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| OR (95% CI)e | Pe | OR (95% CI)e | Pe | OR (95% CI)e | Pe | I2 | Pf | ||||||

| rs4711689 | 6p21.1 | TFEB | 41692812 | A/G | 0.85 | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | 3.41×10−5 | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | 2.89×10−4 | 1.11 (1.07–1.15) | 3.92×10−8 | 31 | 0.13 |

| rs2450115 | 8q23.3 | EIF3H | 117624093 | T/C | 0.58 | 1.11 (1.06–1.17) | 9.19×10−6 | 1.11 (1.07–1.16) | 2.94×10–8 | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | 1.24×10−12 | 0 | 0.51 |

| rs6469656 | 8q23.3 | EIF3H | 117647788 | A/G | 0.67 | 1.12 (1.07–1.16) | 2.59×10−7 | 1.10 (1.06–1.15) | 1.55×10−6 | 1.11 (1.08–1.14) | 2.03×10−12 | 38 | 0.07 |

| rs4919687 | 10q24.3 | CYP17A1 | 104595248 | G/A | 0.80 | 1.16 (1.09–1.24) | 7.52×10−6 | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) | 1.91×10−7 | 1.14 (1.10–1.19) | 7.82×10−12 | 0 | 0.48 |

| rs10506868 | 10q25.2 | VTI1A | 114319380 | T/C | 0.28 | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) | 1.00×10−4 | 1.10 (1.05–1.14) | 9.25×10−6 | 1.10 (1.06–1.13) | 3.98×10−9 | 0 | 0.84 |

| rs11064437 | 12p13.3 | SPSB2 | 6982162 | C/T | 0.75 | 1.14 (1.09–1.20) | 2.80×10−7 | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | 2.11×10−5 | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | 4.48×10−11 | 52.5 | 0.03 |

| rs6061231 | 20q13.3 | RPS21 | 60956917 | C/A | 0.91 | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | 8.56×10−8 | 1.18 (1.07–1.28) | 2.20×10−4 | 1.18 (1.13–1.25) | 8.04×10−11 | 0 | 0.47 |

EAF, effect allele frequency; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The closest gene.

The chromosome position (bp) is based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, build 37.

Effect/reference alleles are based on forward allele coding in NCBI, build 37. OR and 95% CI were estimated based on the effect allele (bold).

EAF in controls from all studies combined.

Summary OR (95% CI) and P were obtained from a fixed-effects meta-analysis.

P for heterogeneity across all studies was calculated using Cochran’s Q test.

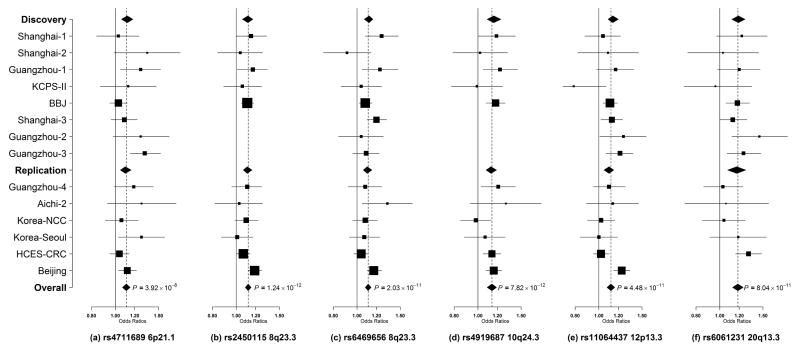

Associations with CRC risk in each of the six risk variants were, in general, consistent across all studies with little evidence of heterogeneity (Figure 1). Stratified analyses by sex and tumor site showed little evidence of heterogeneity (Supplementary Table 4). Except for rs11064437 at 12p13.3 (P = 0.0003), no apparent heterogeneity was found for the association of variants with CRC risk by ethnicity. The heterogeneity with rs11064437 was primarily driven by its null association in studies in South Korea (OR = 1.01, P = 0.73).

Figure 1. Forest plots for newly identified CRC risk variants (a) rs4711689, (b) rs2450115, (c) rs6469656, (d) rs4919687, (e) rs11064437, (f) rs6061231.

Per-allele OR estimates are presented as boxes with the area proportional to the inverse variance of the estimates. Horizontal lines represent the coverage of 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We next evaluated the association of the six newly identified CRC risk variants in populations of European ancestry using data from 16,984 cases and 18,262 controls. With the exception of rs4711689 and rs11064437, all other SNPs were associated with CRC risk at P < 0.05 and in the same direction as observed in East Asian studies (Table 2). There was evidence of heterogeneity in the association of CRC risk with rs4919687, rs4711689 and rs6061231 between populations of European ancestry and East Asian ancestry (P < 0.01). The effect allele frequency (EAF) for all six risk variants differs substantially between European descendants and East Asians (Tables 1–2). For example, for rs11064437, the EAF is 0.75 for East Asians while it is 0.996 for European descendants, which may explain the non-significant finding for this SNP in populations of European ancestry.

Table 2.

Associations of newly identified risk variants with CRC risk in populations of European ancestry (16,984 cases and 18,262 controls)

| Locus | SNP (alleles)a | Geneb | Positionc | EAFd | OR (95% CI)e | Pe | P. hetf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6p21.1 | rs4711689 (A/G) | TFEB | 41692812 | 0.54 | 1.01 (0.97–1.04) | 0.69 | 8.94×10−5 |

| 8q23.3 | rs2450115 (T/C) | EIF3H | 117624093 | 0.81 | 1.08 (1.03–1.12) | 0.0003 | 0.18 |

| 8q23.3 | rs6469656 (A/G) | EIF3H | 117647788 | 0.89 | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| 10q24.3 | rs4919687 (G/A) | CYP17A1 | 104595248 | 0.70 | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| 12p13.3 | rs11064437 (C/T) | SPSB2 | 6982162 | 0.996 | 1.17 (0.85–1.62) | 0.33 | 0.77 |

| 20q13.3 | rs6061231(C/A) | RPS21 | 60956917 | 0.71 | 1.07 (1.04–1.11) | 8.90×10−5 | 0.002 |

EAF, effect allele frequency; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Effect/reference alleles are based on forward allele coding in NCBI, build 37.

the closest gene.

Chromosome position (bp) is based on NCBI Build 37.

EAF from 1000 Genomes Project October 2013 release (CEU+FIN+GBR+IBS+TSI).

The summary OR (95% CI) and P value were obtained from a fixed-effects meta-analysis.

P for heterogeneity between East Asian and European populations was calculated using Cochran’s Q test.

SNPs rs2450115 and rs6469656 lie approximately 24kb apart at 8q23.3, and were correlated only moderately (r2= 0.20, D′ <1 in East Asians). The association with either of these SNPs remained statistically significant (P = 9.60×10−6 for rs2450115 and P = 8.30×10−4 for rs6469656) in the conditional analysis including both SNPs in the same model (Supplementary Table 5), suggesting that there may be two independent association signals. Furthermore, the haplotype (TA) comprising the risk allele of both SNPs was significantly associated with a 1.20-fold increased risk of CRC (P = 1.34 ×10−15) compared to the haplotype (CG) comprising the low-risk allele of both SNPs. These two SNPs lie close to rs16892766 (6.6kb centromeric for rs2450115 and 17 kb telomeric for rs6469656), a CRC-associated variant identified in a previous GWAS in European descendants.17 However, rs16892766 and any of its highly correlated SNPs are monomorphic in East Asian populations. Thus rs16892766 was not in LD with either of the two risk variants identified in our study. Even in European-ancestry populations, these two SNPs also are poor surrogates for rs16892766 (r2 = 0.02, D′=1 for rs2450115 and r2 = 0.01, D′<1 for rs6469656). Interestingly, neither rs2450115 nor rs6469656 was reported to be associated with CRC risk in two previous fine-mapping studies of 8q23.3 for CRC risk in European descendants.31, 32 In our study with a larger sample size, we showed that rs2450115 and rs6469656 were associated with CRC risk in European descendants (P = 0.0003 and 0.02, respectively, Table 2). These two SNPs are in LD with each other in European descendants (r2 = 0.40, D′=1), and only SNP rs2450115 remained statistically significant in the conditional analysis including both SNPs in the model (P = 0.007 for rs2450115 and P = 0.78 for rs6469656).

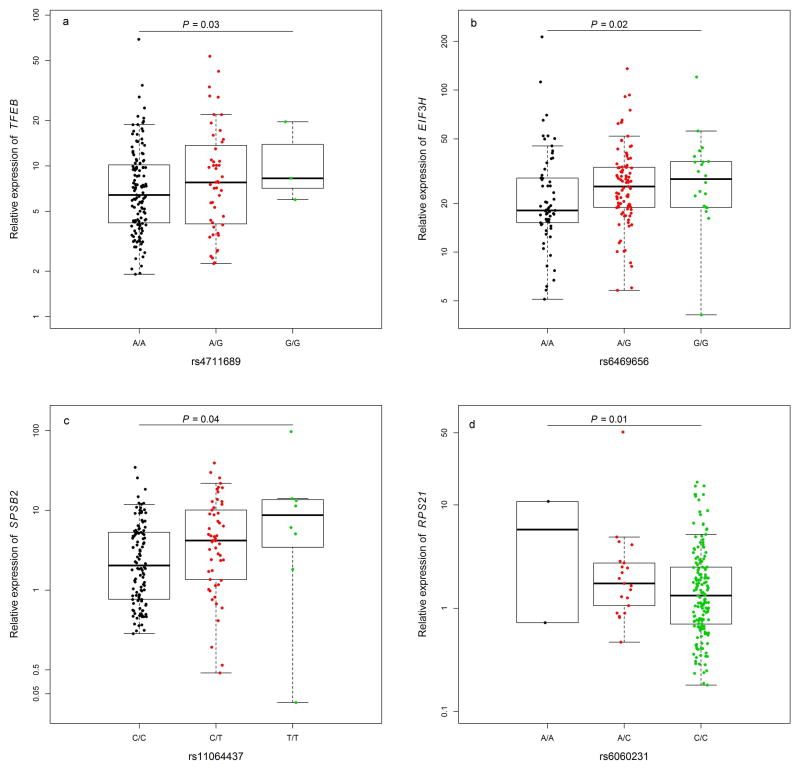

We analyzed the expression levels of the nearest genes in adjacent normal tissues obtained from 188 CRC patients of East Asian ancestry and performed expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analysis. CYP17A1 expression is largely confined to adrenal and gonadal tissues in adults, and thus was not detected in our samples. The remaining four genes evaluated were all highly expressed in normal colorectal tissues. Of the two variants evaluated at 8q23.3, only rs6469656 was significantly correlated with EIF3H expression at P < 0.05 (Figure 2). For the remaining three loci, each of the risk variants was statistically significantly correlated with its nearest gene at P < 0.05 (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 6). At 8q23.3, we also evaluated the expression of the UTP23 gene, a candidate gene suggested by a previous fine-mapping study at this locus.31 However, we did not find any statistically significant correlation of risk variants at 8q23.3 with UTP23 expression (P = 0.90 and 0.74, respectively, for rs2450115 and rs6469656). To evaluate the correlation of mRNA and protein levels for the four genes whose expression levels were significantly associated with the risk variants, we analyzed the protein level for each of these genes in adjacent normal tissues obtained from 16 patients (Supplementary Figure 1). The null hypothesis was that there would be no correlation between mRNA and protein levels. The correlation (r) between mRNA expression and protein level was −0.76, 0.64, −0.42 and 0.58 for TFEB, EIF3H, SPSB2 and RPS21, respectively (P = 0.05, 0.12, 0.07 and 0.24, respectively).

Figure 2. Expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analyses in samples of normal colorectal mucosa adjacent to the tumor obtained from 188 CRC patients of East Asian ancestry.

a. TFEB relative expression and genotypes of rs4711689; b. EIF3H relative expression and genotypes of rs6469656; c. SPSB2 relative expression and genotypes of rs11064437; d. RPS21 relative expression and genotypes of rs6061231.

To evaluate whether the expressions of these genes were deregulated in tumor tissues, we evaluated the differences between tumor and normal tissues in the expression level of the EIF3H, UTP23, SPSB2, TFEB and RPS21 genes using data from the 188 patients mentioned above. With the exception of TFEB, expression levels of the other four genes were significantly higher in tumors (P < 0.005, Supplementary Table 6). For TFEB, the expression level in tumors was significantly lower than normal tissues (P = 9.26 ×10−11, Supplementary Table 6).

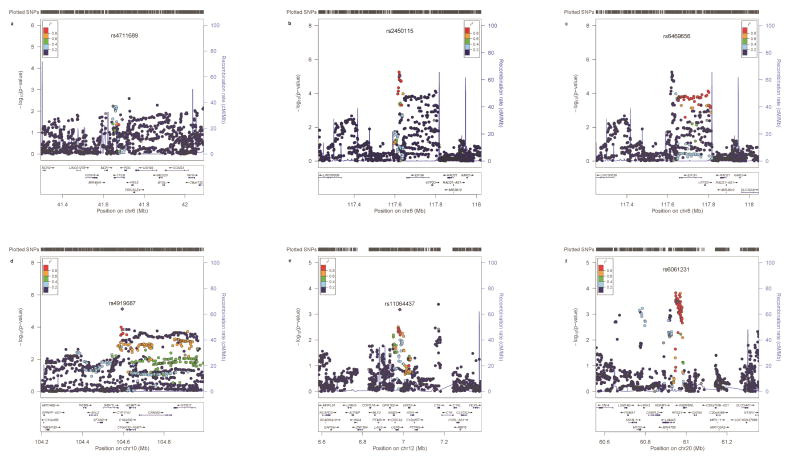

We used publically available functional genomic data to further annotate the risk loci identified in our study. We observed an overlap of promoter and enhancer sequences at each locus and identified multiple potential target genes. Combining results from eQTL analyses, functional annotation, and literature review, as provided in detail in the discussion section, we proposed the likely candidate gene: TFEB at 6p21.1, EIH3H at 8q23.3, CYP17A1 at 10q24.3, SPSB2 at 12p13.3 and RPS21 at 20q13.3. The results of in silico functional annotation of the newly identified loci and literature review on potential roles of candidate genes are summarized in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 7. Regional association plots and functional genomic landscapes of these loci are presented in Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 2.

Table 3.

Summary of risk variants, potential regulatory roles and the likely candidate gene in each new CRC risk locus identified in this study

| SNP (Locus) | Genomic annotation | No. of genes in 1-M window | No. of correlated SNPs (r2 > 0.20) | Potential regulatory roles | The likely candidate gene | Expression difference in tumor vs. adjacent normal tissues* | Biological functions | Known roles in cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4711689 (6p21.1) | Intron 6 of TFEB | 43 | 17 | Promoter, enhancer | TFEB | Down-regulated | Lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy | Oncogenic transcriptional factor for some cancers |

| rs2450115 (8q23.3) | 3′ of EIF3H | 12 | 65 | Unknown | - | - | - | - |

| rs6469656 (8q23.3) | 3′ of EIF3H | 13 | 125 | Promoter, enhancer | EIF3H | Up-regulated | Translational initiation | Promotion of protein synthesis and cancer cell proliferation |

| rs4919687 (10q24.3) | Intron 1 of CYP17A1 | 40 | 412 | Promoter, enhancer | CYP17A1 | N/A | Steroid biogenesis | Modification of hormone level |

| rs11064437 (12p13.3) | Splice receptor at intron 1 of SPSB2 | 79 | 108 | Promoter, enhancer | SPSB2 | Up-regulated | Proteasomal degradation | Less known |

| rs6061231 (20q13.3) | 5′ flanking of RPS21 | 52 | 126 | Promoter, enhancer | RPS21 | Up-regulated | Ribosome biogenesis | Potential cancer driver for CRC |

The expression of each gene was evaluated in paired tumor and adjacent normal colorectal mucosal samples from 188 East Asian patients.

Figure 3. Regional association plots of the risk loci (a) rs4711689 at 6p21.1i;(b) rs2450115 at 8q23.3;(c) rs6469656 at 8q23.3; (d) rs4919687 at 10q24.3; (e) rs11064437 at 12p13.3; (f) rs6061231 at 20q13.3.

In each plot, the log10 (P-values) (y axis) for the association of SNPs with CRC risk are shown according to their chromosomal positions (x axis) in NCBI Build 37. Blue lines represent the estimated recombination rates from the 1000 Genomes Project (Phase 3). Arrows indicate genomic locations of genes within the 1Mb regions centered on the newly-identified risk variants. The color of the SNP represents its LD (r2) with the index SNP at each locus. Only results from the GWAS studies (4,508 cases /16,588 controls in total) are shown. The plots were generated using the online tool LocusZoom.59

We evaluated the association of all GWAS-identified CRC genetic susceptibility loci with data available in our study (Supplementary Table 9). We replicated all 10 risk loci initially identified in GWAS conducted in East Asians at P < 5 × 10−8. Of the 27 risk variants initially identified in European descendants, 21 were associated with CRC risk at P < 0.05 in East Asians in the same direction as reported previously. In particular, variants at 1q41, 8q24.21, 10p14 and 18q21.1 were associated with CRC risk at P < 5 × 10−8. SNPs rs6691170, rs16892766, rs35360328, rs3184504, rs73208120, rs72647484 and rs17094983 are monomorphic in East Asian descendants, and thus we were not able to evaluate their associations in our study. We also did not evaluate the X-chromosome SNP rs5934683, for which the genotype data were not available in our study.

Discussion

In this multiple-staged GWAS with a total of 19,071 cases and 34,624 controls, we identified four novel risk loci for CRC (6p21.1, 8q23.3, 10q24.3 and 12p13.3) and new variants in two previously GWAS-identified loci (10q25.2 and 20q13.3). Using gene expression data from 188 CRC patients of East Asian ancestry, we identified potential candidate genes including TFEB, EIF3H, SPSB2 and RPS21.

At 12p13.3, rs11064437 lies at a splice receptor site within intron 1 of SPSB2. The T allele of rs11064437 changes the splice site from TC (canonical site AG33 on the reverse strand) to TT, and is predicted to disrupt the splicing and introduce a transcriptional isoform with a shortened untranslated region at exon 2 (Supplementary Figure 3). Using data in colon tumor tissues from TCGA, we found a suggestive association of the T allele of rs11064437 with the relative abundance of this isoform (P = 0.11, Supplementary Figure 4). In addition, some of the highly correlated variants were mapped to an active promoter region of SPSB2 in normal colorectal cells (Supplementary Figure 2). These findings, together with results from the eQTL analysis in CRC patients, suggested that variants at 12p13.3 might contribute to CRC risk by regulating the expression of SPSB2. Previous studies have shown that alternative splicing of untranslated regions of exons can affect the stability34 and translation efficiency of pre-mRNAs.35 Similarly, it is possible that rs11064437 may affect post-transcriptional regulation of SPSB2. Misregulated pre-mRNA splicing, which produces aberrant isoforms, has been found to contribute to tumorigenesis.36 Therefore, rs11064437 may be one of the causal variants for the association observed at this locus. Future experiments evaluating SPSB2 splicing diversity and its relevance for the observed association are needed to elucidate the role of this variant. SPSB2 encodes a protein with a suppressor of cytokine signaling domain that functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and a SPRY domain that recognizes substrate for ubiquitination and degradation.37 This protein is predicted to regulate the expression of interacting proteins by targeting them for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation.38 For example, SPSB2 specifically interacts with the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), promotes its degradation and decreases the NO production.38 Selective inhibitors of iNOS have been proposed for chemoprevention of CRC.39 Nonetheless, there were other potential target genes at this locus, such as ENO2, CDCA3 and USP5 (Supplementary Table 7).

At 6p21.1, rs4711689 lies in intron 6 of TFEB. This SNP and its highly correlated SNPs were mapped to a region with enhancer activities in normal colorectal tissues (Supplementary Figure 2). Using enhancer-promoter interaction data derived by the FANTOM5 project, we identified TFEB as a potential target gene (enhancer near rs4711689 (chr6:41672431-41703298) and TFEB expression pairwise correlation r =0.33, FDR < 2.2 ×10−16). Together with the eQTL analysis at this locus, we proposed that TFEB was a likely candidate gene at this locus. TFEB encodes a basic helix-loop helix leucine zipper transcription factor, which has been found to be oncogenic for melanoma,40 renal cell carcinoma41 and some sarcomas.42 However, the role of TFEB in CRC is unknown. Recent studies have shown that this gene is a master regulator of the autophagy-lysosome pathway and of energy metabolism.43 Deregulated autophagy has been linked to cancer initiation and progression.44 These pieces of evidence further support our hypothesis that TFEB is the likely candidate gene at this locus. Notably, TFEB activation is regulated by mTORC1 signaling45, which is thought to be one of the fundamental mechanisms for sustaining tumor growth in CRC.46 It is possible that TFEB may contribute to CRC risk, at least in part, by mediating downstream effects of the mTORC1 pathways. Our results, along with those from previous studies, support a new role for TFEB and provide clues for future studies on the contribution of autophagy deregulation to colorectal etiology.

At 10q24.3, rs4919687 lies in intron 1 of the gene CYP17A1. This gene encodes a membrane-bound dual-function monooxygenase that catalyzes both 17α-hydroxylase and 17, 20-lyase activities to produce androgenic and estrogenic sex steroids, which is the key branch point in steroidogenesis. Epidemiological studies suggest that steroid hormones may be associated with risk of CRC and other cancers.47 Thought to affect steroid hormone levels, CYP17A1 variants, particularly promoter variant rs743572, have been extensively studied in association with risk of hormone-related cancers; 48, 49 however, the results were very inconsistent. Interestingly, this promoter variant (rs743572) is correlated with the risk variant rs4919687 identified in our study (r2 = 0.24, D′<1 in East Asians and r2 = 0.67, D′=1 in European descendants). We herein provide, for the first time, convincing evidence for an association of CYP17A1 gene variants with CRC risk, suggesting that steroid hormones may indeed play a role in the etiology of CRC.

At 8q23.3, two risk variants were identified in our study. Consistent with results from our eQTL analyses, rs2450115 and its correlated variants were mapped to a region of a quiescent state in both normal and cancerous colorectal cells (Supplementary Figure 2), suggesting that these DNAs may be largely inactive, while some variants that are highly correlated with rs6469656 were mapped to active promoter regions of the gene EIF3H (Supplementary Figure 2). Thus, it is likely that some of these variants might be involved in the transcriptional regulation of EIF3H. Together with the evidence from the eQTL analysis, we identified EIF3H as a likely target gene for variants at this locus. EIF3H encodes a subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3. An oncogenic role of this gene was demonstrated by its ability to transform NIH-3T3 cells into their malignant forms.50 Recent studies have shown that EIF3H promoted cancer cell growth by stimulating protein synthesis.51 Another possible candidate gene at this locus is RAD21 (Supplementary Figure 2), which encodes a subunit of cohesin that involves chromosome segregation and DNA repair. A recent study showed that RAD21 was a pivotal mediator of APC heterozygous loss, the event initiating colorectal tumorigenesis.52

At 20q13.3, rs6061231 lies 5.2kb upstream of the gene RPS21, and 36kb telomeric to rs4925386 (r2 = 0.15, D′ <1 in East Asians and r2 = 0.44, D′ <1 European descendants), a risk variant identified in a previous GWAS conducted in populations of European ancestry.27 However, rs4925386 showed a much weaker association with CRC risk (OR = 1.05, P = 0.06) than rs6061231 (OR = 1.20, P = 2.06 ×10−6) in our analysis of 2,098 cases and 6,172 controls of East-Asian ancestry for which these two SNPs were genotyped (Supplementary Table 8). The association with rs6061231 remained statistically significant, while the association with rs4925386 diminished in the conditional analysis including both SNPs in the model (Supplementary Table 8), indicating that the association signal at 20q13.3 was better captured by rs6061231 in East Asians. SNP rs6061231 and some of its highly correlated SNPs were mapped to a 5′ flanking region of RPS21 (Supplementary Figure 2), suggesting that these variants might affect the transcriptional activities of RPS21. In line with evidence from eQTL analysis, these epigenomic data supported the hypothesis that RPS21 was the likely target gene. RPS21 encodes a ribosomal protein that is a component of the 40S subunit of ribosomes. However, its role in tumorigenesis remains unclear. A recent study that characterized differences in eQTLs between tumor and matched normal colon tissues showed that RPS21 had a significantly higher allelic-specific expression somatic event rate and suggested that this gene was a potential driver in CRC.53 This finding further supported that RPS21 played a role in CRC etiology.

In the analysis comparing mRNA and protein levels in adjacent normal tissues, we observed a positive correlation of the mRNA level and protein abundance for the EIF3H and RPS21 genes. For the TFEB and SPSB2 genes, however, their mRNA and protein levels were inversely correlated, although the correlation for the SPSB2 gene was not statistically significant. Although we could not rule out the possibility of chance finding for the inverse correlation, TFEB and SPSB2 are regulatory proteins that are likely to be unstable but have stable mRNAs in steady-state cells. As suggested by previous studies,54 such proteins are predisposed to rapid translational regulation, and thus may sometimes show an inverse correlation of their mRNAs. On the other hand, EIF3H and RPS21 are structural proteins with stable mRNAs and proteins, for which mRNA levels may explain a majority of the variation in protein levels, according to previous studies of proteomics in colon tumors cells and other mammalian cells. 55

By comparing the expression level of candidate genes in tumors with adjacent normal tissues, we showed that these genes were deregulated in tumor tissues, suggesting a possible role of these genes in the development of CRC. For example, the down regulation of TFEB, the master regulator of autophagy, in tumor tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues suggests a decreased level of autophagy in the tumors, which was consistent with previous studies showing that autophagy was suppressed in certain cancer cells.56 Furthermore, it has been proposed that TFEB is a druggable target for autophagy induction therapy57 that has been suggested as a treatment for some cancers. 58

We found that more than three quarters of the risk variants initially identified in GWAS conducted in European descendants were directly replicated in East Asians at P < 0.05, indicating that European and East Asian descendants share most of the genetic risk variants for CRC. However, the strength of the association for some of these risk variants was weaker in East Asians than European descendants. Furthermore, approximately 25% of the risk variants identified initially in studies of European descendants were not replicated in our study, including 7 SNPs that are monomorphic in Asians. Not replicating some of the known risk variants is expected given the difference in LD patterns between Asian and European-ancestry populations. It is likely that other variants in these loci may be associated with CRC risk, and fine-mapping studies are needed to identify these variants.

Our study has several limitations. Multiple participating studies did not collect information for family history of CRC, preventing us from evaluating the possible interaction between family history and these risk variants with adequate power, particularly since the prevalence of family history of CRC is low in the study populations. We evaluated eQTLs only for the genes closest to the risk variants identified in this study. However, it is possible that these risk variants might be correlated with other genes. Future studies are needed to fully uncover the biologic mechanism for the associations observed at these novel loci.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the largest GWAS conducted to date to search for novel genetic susceptibility loci for CRC. Our study provides strong evidence for possible roles of SPSB2, TFEB, EIF3H, CYP17A1 and RPS21 in the etiology of CRC. These genes are involved in different aspects of cellular homeostasis, from translational initiation, protein synthesis, to proteasomal degradation and lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy, highlighting the connection of homeostatic regulation and CRC etiology. Aberrant regulation of intestinal epithelial homeostasis plays an important role in the initiation and progression of CRC. Our study has provided additional insights into the genetics and biology of CRC. Results from our study will be helpful for future studies to uncover molecular mechanisms of CRC tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

The work at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants R01CA188214, R37CA070867, R01CA124558, and R01CA148667 as well as Ingram Professorship and Anne Potter Wilson Chair funds from the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. Sample preparation and genotyping assays at Vanderbilt University were conducted at the Survey and Biospecimen Shared Resources and Vanderbilt Microarray Shared Resource, which are supported in part by the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (P30CA068485). Imputation and statistical analyses were performed at the servers maintained by the Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education at Vanderbilt University. Studies (grant support) participating in the Asia Colorectal Cancer Consortium include the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (US NIH, R37CA070867, UM1CA182910), the Shanghai Men’s Health Study (US NIH, R01CA082729, UM1CA173640), the Shanghai Breast and Endometrial Cancer Studies (US NIH, R01CA064277 and R01CA092585; contributing only controls), Shanghai Colorectal Cancer Study 3 (US NIH, R37CA070867, R01CA188214 and Ingram Professorship funds), the Guangzhou Colorectal Cancer Study (National Key Scientific and Technological Project, 2011ZX09307-001-04; the National Basic Research Program, 2011CB504303, contributing only controls; the Natural Science Foundation of China, 81072383, contributing only controls), the Japan BioBank Colorectal Cancer Study (grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of the Japanese government), the Hwasun Cancer Epidemiology Study–Colon and Rectum Cancer (HCES-CRC; grants from Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, HCRI15011-1). The Aichi Colorectal Cancer Study (Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research, grant for the Third Term Comprehensive Control Research for Cancer and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 17015018 and 221S0001), the Korea-NCC (National Cancer Center) Colorectal Cancer Study (Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, 2010-0010276 and 2013R1A1A2A10008260; National Cancer Center Korea, 0910220), and the KCPS-II Colorectal Cancer Study (National R&D Program for Cancer Control, 1220180; Seoul R&D Program, 10526).

Participating studies (grant support) in the GECCO, CORECT and CCFR GWAS meta-analysis are GECCO (US NIH, U01CA137088 and R01CA059045), DALS (US NIH, R01CA048998), DACHS (German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, BR 1704/6-1, BR 1704/6-3, BR 1704/6-4, CH 117/1-1, 01KH0404 and 01ER0814), HPFS (P01 CA 055075, UM1 CA167552, R01 CA137178, R01 CA151993 and P50 CA127003), NHS (UM1 CA186107, R01 CA137178, P01 CA87969, R01 CA151993 and P50 CA127003), OFCCR (US NIH, U01CA074783), PMH (US NIH, R01CA076366), PHS (US NIH, R01CA042182), VITAL (US NIH, K05CA154337), WHI (US NIH, HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C) and PLCO (US NIH, Z01CP 010200, U01HG004446 and U01HG 004438). CORECT is supported by the National Cancer Institute as part of the GAME-ON consortium (US NIH, U19CA148107) with additional support from National Cancer Institute grants (R01CA81488 and P30CA014089), the National Human Genome Research Institute at the US NIH (T32HG000040) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the US NIH (T32ES013678). CCFR is supported by the National Cancer Institute, US NIH under RFA CA-95-011 and through cooperative agreements with members of the Colon Cancer Family Registry and principal investigators of the Australasian Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (US NIH, U01CA097735), the Familial Colorectal Neoplasia Collaborative Group (US NIH, U01CA074799) (University of Southern California), the Mayo Clinic Cooperative Family Registry for Colon Cancer Studies (US NIH, U01CA074800), the Ontario Registry for Studies of Familial Colorectal Cancer (US NIH, U01CA074783), the Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (US NIH, U01CA074794) and the University of Hawaii Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (US NIH, U01CA074806). The GWAS work was supported by a National Cancer Institute grant (US NIH, U01CA122839). OFCCR was supported by a GL2 grant from the Ontario Research Fund, Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Cancer Risk Evaluation (CaRE) Program grant from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. T.J. Hudson and B.W. Zanke are recipients of Senior Investigator Awards from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, through support from the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation. ASTERISK was funded by a Regional Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC) and supported by the Regional Council of Pays de la Loire, the Groupement des Entreprises Françaises dans la Lutte contre le Cancer (GEFLUC), the Association Anne de Bretagne Génétique and the Ligue Régionale Contre le Cancer (LRCC).

The authors are solely responsible for the scientific content of this paper. The sponsors of this study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the report or the decision for submission. We thank all study participants and research staff of all parent studies for their contributions and commitment to this project. We thank Vanderbilt staff members Jing He for data processing and analyses and Kimberly Kreth for editing and preparing the manuscript. We thank Dr. Bing Zhang, Vanderbilt University for his suggestions on protein validation. Sample preparation and genotyping assays at Vanderbilt University were conducted at the Survey and Biospecimen Shared Resources and Vanderbilt Microarray Shared Resource, which are supported in part by the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (P30CA068485). Imputation and statistical analyses were performed at the servers maintained by the Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education at Vanderbilt University. Studies (grant support) participating in the Asia Colorectal Cancer Consortium include the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (US NIH, R37CA070867), the Shanghai Men’s Health Study (US NIH, R01CA082729), the Shanghai Breast and Endometrial Cancer Studies (US NIH, R01CA064277 and R01CA092585; contributing only controls), Shanghai Colorectal Cancer Study 3 (US NIH, R37CA070867, R01CA188214 and Ingram Professorship funds), the Guangzhou Colorectal Cancer Study (National Key Scientific and Technological Project, 2011ZX09307-001-04; the National Basic Research Program, 2011CB504303, contributing only controls; the Natural Science Foundation of China, 81072383, contributing only controls), the Japan BioBank Colorectal Cancer Study (grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of the Japanese government), the Hwasun Cancer Epidemiology Study–Colon and Rectum Cancer (HCES-CRC; grants from Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, HCRI15011-1). The Aichi Colorectal Cancer Study (Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research, grant for the Third Term Comprehensive Control Research for Cancer and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 17015018 and 221S0001), the Korea-NCC (National Cancer Center) Colorectal Cancer Study (Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, 2010-0010276 and 2013R1A1A2A10008260; National Cancer Center Korea, 0910220), and the KCPS-II Colorectal Cancer Study (National R&D Program for Cancer Control, 1220180; Seoul R&D Program, 10526).

The paired colorectal tumor and adjacent normal tissues and data used for the gene expression analysis were provide by the Biobank of Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, a member of the Korea Biobank Network and General Department, Tangdu Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China.

We also thank all participants, staff and investigators from the GECCO, CORECT and CCFR consortia for making it possible to present results from populations of European ancestry for the new CRC-associated loci identified among East Asians. GECCO, CORECT and CCFR are directed by U. Peters, S. Gruber and G. Casey, respectively. Complete lists of investigators from the GECCO, CORECT and CCFR consortia are provided below.

Investigators (institution and location) in the GECCO consortium include (in alphabetical order): John A. Baron (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA), Sonja I. Berndt (Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, US NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), Stéphane Bezieau (Service de Génétique Médicale, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) Nantes, Nantes, France), Hermann Brenner (Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany), Bette J. Caan (Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program, Oakland, California, USA), Christopher S. Carlson (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA), Graham Casey (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Andrew T. Chan (Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA and Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), Jenny Chang-Claude (Division of Cancer Epidemiology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany), Stephen J. Chanock (Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, US NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), David V. Conti (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Keith Curtis (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), David Duggan (Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, Arizona, USA), Charles S. Fuchs (Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, USA and Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), Steven Gallinger (Department of Surgery, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada and Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), Edward L. Giovannucci (Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA and Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), Stephen B. Gruber (University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Robert W. Haile (Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, CA ), Tabitha A. Harrison (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Richard B. Hayes (Division of Epidemiology, Department of Environmental Medicine, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA), Michael Hoffmeister (Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany), John L. Hopper (Melbourne School of Population Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), Li Hsu (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA and Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA), Thomas J. Hudson (Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada and Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), David J. Hunter (Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), Carolyn M. Hutter (Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, US NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), Rebecca D. Jackson (Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA), Mark A. Jenkins (Melbourne School of Population Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), Shuo Jiao (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Sébastien Küry (Service de Génétique Médicale, CHU Nantes, Nantes, France), Loic Le Marchand (Epidemiology Program, University of Hawaii Cancer Center, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA), Mathieu Lemire (Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), Noralane M. Lindor (Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA), Jing Ma (Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), Polly A. Newcomb (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA and Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington, USA), Ulrike Peters (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA and Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington, USA), John D. Potter (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington, USA and Centre for Public Health Research, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand), Conghui Qu (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Robert E. Schoen (Department of Medicine and Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA), Fredrick R. Schumacher (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Daniela Seminara (Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, US NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), Martha L. Slattery (Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA), Stephen N. Thibodeau (Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA and Department of Laboratory Genetics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA), Emily White (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA and Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington, USA) and Brent W. Zanke (Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Investigators (institution and location) from the CORECT consortium include (in alphabetical order): Kendra Blalock (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Peter T. Campbell (Epidemiology Research Program, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia, USA), Graham Casey (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), David V. Conti (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Christopher K. Edlund (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Jane Figueiredo (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), W. James Gauderman (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Jian Gong (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Roger C. Green (Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada), Stephen B. Gruber (University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), John F. Harju (University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA), Tabitha A. Harrison (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Eric J. Jacobs (Epidemiology Research Program, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia, USA), Mark A. Jenkins (Melbourne School of Population Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), Shuo Jiao (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Li Li (Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA), Yi Lin (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Frank J. Manion (University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA), Victor Moreno (Institut d’Investigació Biomèdica de Bellvitge, Institut Catala d’Oncologia, Hospitalet, Barcelona, Spain), Bhramar Mukherjee (University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA), Ulrike Peters (Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA), Leon Raskin (University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Fredrick R. Schumacher (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA), Daniela Seminara (Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, US NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), Gianluca Severi (Melbourne School of Population Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), Stephanie L. Stenzel (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA) and Duncan C. Thomas (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA).

The CCFR consortium is represented by Graham Casey (Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA).

We also thank B. Buecher of ASTERISK; U. Handte-Daub, M. Celik, R. Hettler-Jensen, U. Benscheid and U. Eilber of DACHS; and P. Soule, H. Ranu, I. Devivo, D.J. Hunter, Q. Guo, L. Zhu and H. Zhang of HPFS, NHS and PHS, as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington and Wyoming. We thank C. Berg and P. Prorok of PLCO; T. Riley of Information Management Services, Inc.; B. O’Brien of Westat, Inc.; B. Kopp and W. Shao of SAIC-Frederick; the WHI investigators (see http://www.whi.org/researchers/Documents%20%20Write%20a%20Paper/WHI%20Investigator%20Short%20List.pdf) and the GECCO Coordinating Center. The authors acknowledge Dave Duggan and team members at TGEN (Translational Genomics Research Institute), the Broad Institute, and the Génome Québec Innovation Center for genotyping DNA samples of cases and controls in GECCO, and for scientific input for GECCO. Participating studies (grant support) in the GECCO, CORECT and CCFR GWAS meta-analysis are GECCO (US NIH, U01CA137088 and R01CA059045), DALS (US NIH, R01CA048998), DACHS (German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, BR 1704/6-1, BR 1704/6-3, BR 1704/6-4, CH 117/1-1, 01KH0404 and 01ER0814), HPFS (P01 CA 055075, UM1 CA167552, R01 137178, R01 CA151993 and P50 CA127003), NHS (UM1 CA186107, R01 CA137178, P01 CA87969, R01 CA151993 and P50 CA127003), OFCCR (US NIH, U01CA074783), PMH (US NIH, R01CA076366), PHS (US NIH, R01CA042182), VITAL (US NIH, K05CA154337), WHI (US NIH, HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C) and PLCO (US NIH, Z01CP 010200, U01HG004446 and U01HG 004438). CORECT is supported by the National Cancer Institute as part of the GAME-ON consortium (US NIH, U19CA148107) with additional support from National Cancer Institute grants (R01CA81488 and P30CA014089), the National Human Genome Research Institute at the US NIH (T32HG000040) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the US NIH (T32ES013678). CCFR is supported by the National Cancer Institute, US NIH under RFA CA-95-011 and through cooperative agreements with members of the Colon Cancer Family Registry and principal investigators of the Australasian Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (US NIH, U01CA097735), the Familial Colorectal Neoplasia Collaborative Group (US NIH, U01CA074799) (University of Southern California), the Mayo Clinic Cooperative Family Registry for Colon Cancer Studies (US NIH, U01CA074800), the Ontario Registry for Studies of Familial Colorectal Cancer (US NIH, U01CA074783), the Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (US NIH, U01CA074794) and the University of Hawaii Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (US NIH, U01CA074806). The GWAS work was supported by a National Cancer Institute grant (US NIH, U01CA122839). OFCCR was supported by a GL2 grant from the Ontario Research Fund, Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Cancer Risk Evaluation (CaRE) Program grant from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. T.J. Hudson and B.W. Zanke are recipients of Senior Investigator Awards from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, through support from the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation. ASTERISK was funded by a Regional Hospital Clinical Research Program (PHRC) and supported by the Regional Council of Pays de la Loire, the Groupement des Entreprises Françaises dans la Lutte contre le Cancer (GEFLUC), the Association Anne de Bretagne Génétique and the Ligue Régionale Contre le Cancer (LRCC). PLCO data sets were accessed with approval through dbGaP (CGEMS prostate cancer scan, phs000207.v1.p1 (Yeager, M et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat Genet 2007 May;39(5):645-9); CGEMS pancreatic cancer scan, phs000206.v4.p3 (Amundadottir, L et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Nat Genet. 2009 Sep;41(9):986-90, and Petersen, GM et al. A genome-wide association study identifies pancreatic cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 13q22.1, 1q32.1 and 5p15.33. Nat Genet. 2010 Mar;42(3):224-8); and GWAS of Lung Cancer and Smoking, phs000093.v2.p2 (Landi MT, et al. A genome-wide association study of lung cancer identifies a region of chromosome 5p15 associated with risk for adenocarcinoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 Nov;85(5):679-91), which was funded by Z01CP 010200, U01HG004446 and U01HG 004438 from the US NIH).

Abbreviations

- ACCC

Asia Colorectal Cancer Consortium

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CYP17A1

cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1

- EIF3H

Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3, Subunit H

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- RPS21

ribosomal protein S21

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SPSB2

splA/ryanodine receptor domain and SOCS box containing 2

- TFEB

transcription factor EB

- VTI1A

vesicle transport through interaction with t-SNAREs 1A

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing financial, professional, or personal interests.

Author Contributions

W.Z. conceived and directed the Asia Colorectal Cancer Consortium and the Shanghai-Vanderbilt Colorectal Cancer Genetics Project. W.H.J. and Y.X.Z., D.L., K. Matsuda, S.S.K., K. Matsuo, X.O.S., Y.B.X. and Y.T.G., A.S., S.H.J., D.H.K., U.P., S.B.G, and G.C. directed CRC projects in Guangzhou, Beijing, BBJ, HCES-CRC, Aichi, Shanghai, Korea-NCC, KCPS-II, Korea-Seoul, GECCO, CORECT, and CCFR, respectively. C.Z. and W.Z. wrote the paper with significant contributions from X.O.S., Q.C., J.L., W.W., B.L. and X.G. Q.C. coordinated the project and directed the lab operations. N.W. and J.W. performed the gene expression experiments. Q.C. and R.C. performed the Western blot analysis. J.W. and J.S. performed the genotyping experiments. C.Z., B.Z. and W.W. performed the statistical analyses. C.Z. and X.G. performed the bioinformatics analyses. A.T. conducted the statistical analyses and imputation for BBJ. C.Z. and J.L. managed the data. All authors contributed to data and biological sample collection in the original studies included in this project and/or manuscript revision. J.C. and C.W. contributed to data and biological sample collection for the study in Beijing. H.B., J.A.B., K.B., S.B., S.I.B., A.T.C., B.J.C., C.S.C., D.V.C., G.C., K.C., P.T.C., S.J.C., J.C.-C., D.D., C.K.E., C.S.F., J.F., E.L.G., J.G., R.C.G., S.G., S.B.G., W.J.G., C.M.H., D.J.H., J.D.H., J.F.H., J.L.H., L.H., M.H., R.B.H., R.W.H., T.A.H., T.J.H., E.J.J., M.A.J., R.D.J., S.J., S.K., L.L., M.L., N.M.L., Y.L., L.Le Marchand, B.M., F.J.M., J.M., V.M., P.A.N, J.D.P., U.P., C.Q., L.R., T.R., D.S., F.R.S., G.S., M.L.S., R.E.S., S.L.S., D.C.T., S.N.T., E.W., E.W. and B.W.Z. contributed to data and biological sample collection for the studies included in GECCO, CORECT and CCFR. All authors have reviewed and approved the content of the paper.

URLs

Illumina HumanEXome-12v1_A Beadchip: http://www.illumina.com/products/infinium_humanexome_beadchip_kit.html

Haplo.stats package: http://www.mayo.edu/research/labs/statistical-genetics-genetic-epidemiology/software

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer - Analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343:78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma X, Zhang B, Zheng W. Genetic variants associated with colorectal cancer risk: comprehensive research synopsis, meta-analysis, and epidemiological evidence. Gut. 2014;63:326–36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemire M, Qu C, Loo LW, et al. A genome-wide association study for colorectal cancer identifies a risk locus in 14q23.1. Hum Genet. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00439-015-1598-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schumacher FR, Schmit SL, Jiao S, et al. Genome-wide association study of colorectal cancer identifies six new susceptibility loci. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7138. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Tassan NA, Whiffin N, Hosking FJ, et al. A new GWAS and meta-analysis with 1000Genomes imputation identifies novel risk variants for colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10442. doi: 10.1038/srep10442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Burnett T, Kono S, et al. Trans-ethnic genome-wide association study of colorectal cancer identifies a new susceptibility locus in VTI1A. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4613. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang B, Jia WH, Matsuda K, et al. Large-scale genetic study in East Asians identifies six new loci associated with colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2014;46:533–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiffin N, Hosking FJ, Farrington SM, et al. Identification of susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer in a genome-wide meta-analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4729–37. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters U, Jiao S, Schumacher FR, Hutter CM, et al. Identification of Genetic Susceptibility Loci for Colorectal Tumors in a Genome-Wide Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:799–807. e24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia WH, Zhang B, Matsuo K, et al. Genome-wide association analyses in East Asians identify new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:191–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunlop MG, Dobbins SE, Farrington SM, et al. Common variation near CDKN1A, POLD3 and SHROOM2 influences colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2012;44:770–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houlston RS, Cheadle J, Dobbins SE, et al. Meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies identifies susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer at 1q41, 3q26.2, 12q13.13 and 20q13. 33. Nature Genetics. 2010;42:973–U89. doi: 10.1038/ng.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomlinson IPM, Webb E, Carvajal-Carmona L, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies colorectal cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 10p14 and 8q23. 3. Nature Genetics. 2008;40:623–630. doi: 10.1038/ng.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaeger E, Webb E, Howarth K, et al. Common genetic variants at the CRAC1 (HMPS) locus on chromosome 15q13. 3 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nature Genetics. 2008;40:26–28. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houlston RS, Webb E, Broderick P, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies four new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer. Nature Genetics. 2008;40:1426–1435. doi: 10.1038/ng.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenesa A, Farrington SM, Prendergast JGD, et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on 11q23 and replicates risk loci at 8q24 and 18q21. Nature Genetics. 2008;40:631–637. doi: 10.1038/ng.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomlinson I, Webb E, Carvajal-Carmona L, et al. A genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for colorectal cancer at 8q24. 21. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:984– 988. doi: 10.1038/ng2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broderick P, Carvajal-Carmona L, Pittman AM, Webb E, et al. A genome-wide association study shows that common alleles of SMAD7 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:1315–1317. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanke BW, Greenwood CMT, Rangrej J, et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:989–994. doi: 10.1038/ng2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomlinson IP, Carvajal-Carmona LG, Dobbins SE, et al. Multiple common susceptibility variants near BMP pathway loci GREM1, BMP4, and BMP2 explain part of the missing heritability of colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters U, Bien S, Zubair N. Genetic architecture of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2015 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, et al. MaCH: Using Sequence and Genotype Data to Estimate Haplotypes and Unobserved Genotypes. Genetic Epidemiology. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romanoski CE, Glass CK, Stunnenberg HG, et al. Epigenomics: Roadmap for regulation. Nature. 2015;518:314–6. doi: 10.1038/518314a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Consortium EP. A user’s guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lizio M, Harshbarger J, Shimoji H, et al. Gateways to the FANTOM5 promoter level mammalian expression atlas. Genome Biology. 2015;16 doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–81. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2013;Chapter 7(Unit 7):20. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvajal-Carmona LG, Cazier JB, Jones AM, et al. Fine-mapping of colorectal cancer susceptibility loci at 8q23.3, 16q22.1 and 19q13. 11: refinement of association signals and use of in silico analysis to suggest functional variation and unexpected candidate target genes. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20:2879–2888. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pittman AM, Naranjo S, Jalava SE, et al. Allelic Variation at the 8q23.3 Colorectal Cancer Risk Locus Functions as a Cis-Acting Regulator of EIF3H. Plos Genetics. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burset M, Seledtsov IA, Solovyev VV. Analysis of canonical and non-canonical splice sites in mammalian genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4364–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andolfo I, De Falco L, Asci R, et al. Regulation of divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) non-IRE isoform by the microRNA Let-7d in erythroid cells. Haematologica. 2010;95:1244–52. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.020685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin YS, Yasuda K, Assem M, et al. The major human pregnane X receptor (PXR) splice variant, PXR. 2, exhibits significantly diminished ligand-activated transcriptional regulation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1295–304. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Manley JL. Misregulation of pre-mRNA alternative splicing in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1228–37. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kile BT, Schulman BA, Alexander WS, et al. The SOCS box: a tale of destruction and degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:235–41. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuang Z, Lewis RS, Curtis JM, et al. The SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein SPSB2 targets iNOS for proteasomal degradation. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:129–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janakiram NB, Rao CV. iNOS-selective inhibitors for cancer prevention: promise and progress. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:2193–204. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:406–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuiper RP, Schepens M, Thijssen J, et al. Upregulation of the transcription factor TFEB in t(6;11)(p21;q13)-positive renal cell carcinomas due to promoter substitution. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1661–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis IJ, Kim JJ, Ozsolak F, et al. Oncogenic MITF dysregulation in clear cell sarcoma: defining the MiT family of human cancers. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:473–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Settembre C, De Cegli R, Mansueto G, et al. TFEB controls cellular lipid metabolism through a starvation-induced autoregulatory loop. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:647–58. doi: 10.1038/ncb2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White E. Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:401–10. doi: 10.1038/nrc3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pena-Llopis S, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Schwartz JC, et al. Regulation of TFEB and V-ATPases by mTORC1. Embo Journal. 2011;30:3242–3258. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faller WJ, Jackson TJ, Knight JR, et al. mTORC1-mediated translational elongation limits intestinal tumour initiation and growth. Nature. 2015;517:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature13896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin JH, Giovannucci E. Sex hormones and colorectal cancer: what have we learned so far? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1746–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu J, Lin X, Zhu H, et al. Genetic variation of the CYP17 and susceptibility to endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:5085–91. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao L, Fang F, Wu Q, et al. No association between CYP17 T-34C polymorphism and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis involving 58,814 subjects. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:221–7. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, Pan X, Hershey JW. Individual overexpression of five subunits of human translation initiation factor eIF3 promotes malignant transformation of immortal fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5790–800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahmood SF, Gruel N, Chapeaublanc E, et al. A siRNA screen identifies RAD21, EIF3H, CHRAC1 and TANC2 as driver genes within the 8q23, 8q24. 3 and 17q23 amplicons in breast cancer with effects on cell growth, survival and transformation. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:670–82. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu H, Yan Y, Deb S, et al. Cohesin Rad21 mediates loss of heterozygosity and is upregulated via Wnt promoting transcriptional dysregulation in gastrointestinal tumors. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1781– 97. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]