Abstract

Background

New five-tiered Gleason grade groups (GGGs) were recently proposed, in which Gleason 6 is GGG 1, Gleason 3+4 is GGG 2, Gleason 4+3 is GGG 3, Gleason 8 is GGG 4, and Gleason 9-10 is GGG 5.

Objective

To examine the performance of the new GGGs in men with prostate cancer from a nationwide population-based cohort.

Design, setting, and participants

From the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden, we identified 5880 men diagnosed with prostate cancer from 2005 to 2007, including 4325 who had radical prostatectomy and 1555 treated with radiation therapy.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, Cox proportional hazards models, and concordance indices were used to examine the relationship between the GGGs and biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy.

Results and limitations

Among men treated with surgery, the 4-yr biochemical recurrence-free survival rates were 89%, 82%, 74%, 77%, and 49% for GGG 1–5 on biopsy, and 92%, 85%, 73%, 63%, and 51% based on prostatectomy GGG, respectively. For men treated by radiation therapy, men with biopsy GGG of 1–5 had 4-yr biochemical recurrence-free survival rates of 95%, 91%, 85%, 78%, and 70%. Adjusting for preoperative serum prostate-specific antigen and clinical stage, biopsy GGGs were significant independent predictors of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy. The new 5-tier system resulted in virtually no change in predictive accuracy compared with the current 3- and 4-tier classifications. Limitations include a median follow-up of 4.6 yr, precluding the ability to examine long-term oncologic outcomes.

Conclusions

The newly proposed GGGs offer a simplified, user-friendly nomenclature to aid in patient counseling, with similar predictive accuracy in a population-based setting to previous classifications.

Patient summary

The new Gleason grade groups, ranging from 1–5, provide a simplified, user-friendly classification system to predict the risk of recurrence after prostatectomy and radiation therapy.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Gleason grade, Pathology, ISUP, Epstein

1. Introduction

A new prostate cancer grading scheme has recently been proposed in an effort to better reflect true biologic aggressiveness and guide clinical management [1]. Unlike contemporary Gleason scores which range from 6–10, the new prognostic grade groups use a scale of 1–5. Specifically, Gleason grade group (GGG) 1 is Gleason 6, GGG 2 is 3+4 = 7, GGG 3 is 4+3 = 7, GGG 4 is Gleason 8, and GGG 5 is Gleason 9–10. Thus, using this new system, tumors with the most favorable features are now considered a "1" rather than a "6," and Gleason 7 is split into two separate categories.

As yet, there are limited published data evaluating the new GGGs. A single-institution series of 7869 men undergoing radical prostatectomy (RP) at Johns Hopkins showed that GGGs predicted biochemical recurrence (BCR) at a median follow-up of 2 yr [2]. The 5-yr rates of BCR-free survival were 95%, 83%, 65%, 63%, and 34% for men with GGG 1–5 on biopsy, and 97%, 88%, 70%, 64%, and 34% for GGG 1–5 at prostatectomy, respectively (p < 0.001).

More recently, Epstein et al [3] examined the GGGs in 20–845 men undergoing RP at five academic centers and 5501 men treated with radiation therapy at two academic centers, with a median follow-up of 3 yr. On multivariable analysis, the new GGGs predicted a higher risk of BCR after both RP and radiation therapy.

To date, there are no published studies evaluating the GGGs in a population-based setting, and their predictive value for men undergoing radiation therapy has not yet been examined in an independent population. The objective of our study was to examine the newly proposed grade groups in men undergoing RP and radiation therapy in The National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden.

2. Materials and methods

Since 1998, the NPCR of Sweden has data on 98% of all prostate cancer cases diagnosed nationwide compared with the Swedish Cancer Register to which registration is mandatory [4,5]. As previously described, in the Prostate Cancer data Base, the data from NPCR have been cross-linked to other national health care registers and demographic databases using each individual's personal identity number. As such, Prostate Cancer data Base contains detailed information on both cancer features and primary treatment, as well as data on other important patient characteristics such as Charlson comorbidity index based on discharge diagnoses from the patient register, and educational level, income, and marital status from the Longitudinal Integration Database for health insurance and labor market.

For cases diagnosed in 2003–2007, the NPCR performed a follow-up study of men aged ≤70 yr diagnosed with localized prostate cancer (serum prostate-specific antigen [PSA] < 20 ng/ml, clinical stages T1/T2). Due to changes in Gleason grading at the 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) meeting [6], we limited the current study to men from the follow-up study diagnosed with prostate cancer from 2005 to 2007 (n = 7596), as in the recent study by Epstein et al [3]. Of these men, 6119 underwent RP or radiation therapy. We excluded 114 men with missing biopsy Gleason grade, an additional 64 men with incomplete data on prostatectomy Gleason grade and 61 men with missing date of treatment. Following these exclusions the final study population included 5880 men, including 4325 who had RP and 1555 who received radiation therapy (Supplementary Fig. 1). Outcomes were assessed uniformly in all men by chart review at 5 yr after diagnosis.

Gleason scores were assigned by local pathologists across Sweden. For prostate biopsy, common practice in Sweden is to submit each specimen in a separate container and to separately embed each specimen. Each core is assigned a Gleason score and a global Gleason score is reported in the bottom line. For RP, the specimen is completely embedded with a whole mount preparation to facilitate identification of individual tumor foci.

Biopsy Gleason scores were classified into GGGs as described above: Gleason score 6 is GGG 1, Gleason 3+4 = 7 is GGG 2, Gleason 4+3 = 7 is GGG 3, Gleason 8 is GGG 4, and Gleason 9–10 is GGG 5 [1,2]. For men who underwent RP, the final Gleason scores were also categorized in the same way. BCR was defined as two PSA measurements ≥0.2 ng/ml for men undergoing RP, and two PSA measurements ≥2 ng/ml over the nadir for radiation therapy, with the first of these considered the date of BCR.

Among men in the RP subset, the chi-square test was used to examine associations between biopsy GGG with the following individual pathology features: RP GGG, organ-confined disease, positive surgical margins, and lymph node metastasis. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between biopsy GGG and a composite definition of adverse pathology after prostatectomy (defined as the presence of extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, or lymph node metastases). Additional covariates in the main multivariable models were PSA (continuous, in 1 ng/ml units) and clinical stage (T2 vs T1).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to examine progression-free survival after prostatectomy (using biopsy and prostatectomy GGG) and after radiation therapy (using biopsy GGG), and curves were compared using the log-rank test. We also created Kaplan–Meier curves for prostate cancer specific survival based on biopsy and RP GGG. Follow-up for mortality was complete through December 31, 2013.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were also used to examine BCR, with separate models for patients undergoing RP and radiation therapy. In the main analysis, these models were adjusted for serum PSA (continuous, in 1 ng/ml units) and stage (clinical stage T2 vs T1 in models using biopsy GGG, and organ-confined vs non organ-confined the model with RP GGG). In order to adjust for the age distribution in different grade groups, age was used as the time scale. Separate models were performed adjusting for marital status (not currently married vs married), education level (low, middle, high), Charlson comorbidity index (0, 1, 2+), and hospital type (nonuniversity vs university). In men undergoing radical prostatectomy, a separate Cox model was performed adjusting for pathologic stage and surgical margin status. In the radiation therapy cohort, separate models were performed adjusting for use of neoadjuvant hormonal therapy.

Finally, we also calculated the concordance index for the following Gleason grade classifications for BCR using 10-fold cross-validation: 3-tier system (≤6, 7, and 8–10), 4-tiered system (≤6, 7, 8, and 9–10), and the 5-tier GGG. R version 3.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for all statistical analysis. The study was approved by the research ethics board at Umeå University Hospital.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the demographics of the study population. Overall, 3953 (67%) men had GGG 1 (former Gleason score 6), 1181 (20%) had GGG 2 (Gleason score 3+4), 417 (7%) had GGG 3 (Gleason score 4+3), 255 (4%) had GGG 4 (Gleason score 8), and 74 (1%) had GGG 5 (Gleason score 9–10) on biopsy. The proportion of biopsies positive for cancer is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographics by Gleason grade group for men diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2005–2007 within the 5 yr follow-up study in PCBaSe 3.0 who underwent primary radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy

| Biopsy GGG | GGG 1 (%) | GGG 2 (%) | GGG 3 (%) | GGG 4 (%) | GGG 5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of men | 3953 (100) | 1181 (100) | 417 (100) | 255 (100) | 74 (100) |

| Yr of diagnosis | |||||

| 2005 | 1687 (43) | 445 (38) | 162 (39) | 101 (40) | 25 (34) |

| 2006 | 1352 (34) | 426 (36) | 149 (36) | 87 (34) | 24 (32) |

| 2007 | 914 (23) | 310 (26) | 106 (25) | 67 (26) | 25 (34) |

| Age (yr) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 62.9 (59–66) | 63.5 (60–67) | 64.6 (61–68) | 64.6 (61–68) | 64.3 (61–68) |

| Serum PSA (ng/ml) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 6.4 (4.8–9.1) | 7.0 (5.0–10.0) | 8.1 (5.8–12.0) | 8.0 (5.6–12.0) | 8.6 (5.9–12.8) |

| Clinical stage | |||||

| T1 | 2915 (74) | 718 (61) | 216 (52) | 149 (58) | 29 (39) |

| T2 | 1038 (26) | 463 (39) | 201 (48) | 106 (42) | 45 (61) |

| No. of biopsy cores | |||||

| <6 | 57 (1) | 15 (1) | 12 (3) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) |

| 6–9 | 2475 (63) | 745 (63) | 266 (64) | 163 (64) | 52 (70) |

| 10–12 | 941 (24) | 299 (25) | 89 (21) | 51 (20) | 16 (22) |

| >12 | 24 (1) | 6 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing data | 456 (12) | 116 (10) | 49 (12) | 33 (13) | 6 (8) |

| No. of positive cores | |||||

| 1 | 1246 (32) | 171 (14) | 43 (10) | 66 (26) | 10 (14) |

| 2 | 964 (24) | 199 (17) | 83 (20) | 52 (20) | 8 (11) |

| 3 | 626 (16) | 219 (19) | 110 (26) | 43 (17) | 12 (16) |

| 4–6 | 573 (14) | 394 (33) | 107 (26) | 49 (19) | 29 (39) |

| >6 | 88 (2) | 82 (7) | 25 (6) | 12 (5) | 9 (12) |

| Missing data | 456 (12) | 116 (10) | 49 (12) | 33 (13) | 6 (8) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 2873 (73) | 863 (73) | 293 (70) | 194 (76) | 50 (68) |

| Not married | 1080 (27) | 318 (27) | 124 (30) | 61 (24) | 24 (32) |

| Educational levela | |||||

| Low | 1125 (28) | 351 (30) | 129 (31) | 89 (35) | 33 (45) |

| Middle | 1691 (43) | 492 (42) | 182 (44) | 88 (35) | 28 (38) |

| High | 1124 (28) | 337 (29) | 104 (25) | 77 (30) | 13 (18) |

| Missing data | 13 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||||

| CCI 0 | 3529 (89) | 1033 (87) | 354 (85) | 223 (87) | 58 (78) |

| CCI 1 | 285 (7) | 92 (8) | 41 (10) | 24 (9) | 6 (8) |

| CCI 2+ | 139 (4) | 56 (5) | 22 (5) | 8 (3) | 10 (14) |

| Type of hospital | |||||

| University | 1974 (50) | 636 (54) | 184 (44) | 134 (53) | 43 (58) |

| Nonuniversity | 1979 (50) | 545 (46) | 233 (56) | 121 (47) | 31 (42) |

| Primary treatment | |||||

| Radical prostatectomy | 2992 (76) | 845 (72) | 292 (70) | 162 (64) | 34 (46) |

| Radiotherapy | 961 (24) | 336 (28) | 125 (30) | 93 (36) | 40 (54) |

| Neo-adjuvant ADTb | |||||

| No | 588 (75) | 137 (49) | 40 (37) | 22 (27) | 6 (15) |

| Yes | 196 (25) | 143 (51) | 67 (63) | 59 (73) | 34 (85) |

ADT = androgen-deprivation therapy; CCI = Charlson comorbidity index; IQR = interquartile range; GGG = Gleason grade group; PSA = prostate specific antigen.

Educational levels: low = compulsory school (<10 yr), middle = upper secondary school (10–12 yr), high = college or university (>12 yr).

Only available for men undergoing radiotherapy 2006–2007, any ADT during a 3-mo period before radiotherapy was considered to be neo-adjuvant.

Table 2 shows the relationship between GGG in biopsy and prostatectomy specimens as well as the pathology features per biopsy GGG. On univariable analysis, biopsy GGG had a statistically significant association with RP GGG, pathologic stage, margin status, and lymph node metastases (all p < 0.001). On multivariable analysis, there was a statistically significant relationship between the GGG on biopsy with the presence of one or more adverse features at RP (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Pathology features in prostatectomy specimen by Gleason grade group on biopsy

| Biopsy GGG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| GGG 1 (%) | GGG 2 (%) | GGG 3 (%) | GGG 4 (%) | GGG 5 (%) | |

| No. of men | 2992 (100) | 845 (100) | 292 (100) | 162 (100) | 34 (100) |

| Pathology features | |||||

| Organ confined disease | 2126 (80) | 480 (66) | 159 (62) | 81 (58) | 16 (55) |

| Extracapsular extension | 435 (16) | 197 (27) | 62 (24) | 41 (29) | 4 (14) |

| Seminal vesicle invasion | 93 (4) | 49 (7) | 34 (13) | 18 (13) | 9 (31) |

| Lymph node metastasis | 11 (0) | 9 (1) | 9 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (9) |

| Surgical margin status | |||||

| Negative | 2024 (80) | 493 (74) | 158 (70) | 85 (66) | 16 (55) |

| Positive | 492 (20) | 169 (26) | 68 (30) | 44 (34) | 13 (45) |

| Prostatectomy GGG | |||||

| GGG 1 | 1902 (64) | 184 (22) | 28 (10) | 11 (7) | 2 (6) |

| GGG 2 | 846 (28) | 484 (57) | 97 (33) | 28 (17) | 2 (6) |

| GGG 3 | 192 (6) | 143 (17) | 134 (46) | 66 (41) | 5 (15) |

| GGG 4 | 46 (2) | 24 (3) | 21 (7) | 41 (25) | 3 (9) |

| GGG 5 | 6 (0) | 10 (1) | 12 (4) | 16 (10) | 22 (65) |

GGG = Gleason grade group.

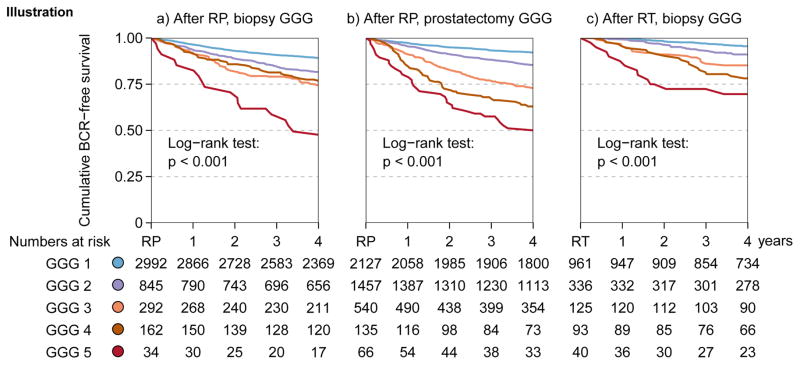

The median follow-up after treatment for men without biochemical recurrence was 4.6 yr (interquartile range, 4.4–4.8). Figure 1A shows significant differences in BCR-free survival after prostatectomy based on GGG 1–5 assessed on biopsy with 4-yr BCR-free survival rates of 89%, 82%, 74%, 77%, and 49% respectively, (p < 0.001, log rank test). On multivariable analysis with PSA and clinical stage, the biopsy GGG remained significant independent predictors of BCR (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for biochemical recurrence-free survival (A) after radical prostatectomy based on biopsy Gleason grade groups (GGG), (B) after radical prostatectomy based on prostatectomy GGG, and (C) after radiation therapy based on biopsy GGG.

BCR = biochemical recurrence; GGG = Gleason grade group; RP = radical prostatectomy; RT = radiotherapy.

Table 3.

Biochemical recurrence after primary treatment according to Gleason grade group in biopsy or prostatectomy specimen

| After RP, biopsy GGG | After RP, prostatectomy GGG | After RT, biopsy GGG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HRa | 95% CIa | HRa | 95% CIa | HRa | 95% CIa | |

| Gleason Grade Group | ||||||

| GGG 1 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| GGG 2 | 1.63 | (1.35–1.97) | 1.72 | (1.41–2.10) | 1.90 | (1.20–3.01) |

| GGG 3 | 2.08 | (1.62–2.67) | 2.86 | (2.28–3.58) | 2.72 | (1.55–4.79) |

| GGG 4 | 2.11 | (1.54–2.90) | 3.43 | (2.47–4.76) | 4.04 | (2.36–6.93) |

| GGG 5 | 4.24 | (2.62–6.86) | 5.75 | (3.96–8.36) | 6.03 | (3.13–11.63) |

| Serum PSA (per 1 ng/mL) | 1.09 | (1.07–1.12) | 1.08 | (1.06–1.10) | 1.08 | (1.04–1.12) |

| T stage b | 1.45 | (1.24–1.71) | 2.40 | (2.04–2.82) | 1.96 | (1.35–2.82) |

CI = confidence interval; GGG = Gleason grade group; HR = hazard ratio; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; RP = Radical prostatectomy, RT = Radiotherapy.

Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals from multivariable Cox regression models.

In the models with biopsy GGG, clinical stage T2 was compared with T1 (reference) and in the model with prostatectomy GGG, non-organ confined disease was compared to organ confined disease (reference).

Similarly, there were also significant differences in BCR-free survival based on assessment of the prostatectomy specimen with 4-yr recurrence-free survival rates of 92%, 85%, 73%, 63%, and 51% (p < 0.001, log rank test; Fig. 1B). On multivariable analysis with PSA and pathologic stage, the prostatectomy GGG remained significant independent predictors of BCR (Table 3).

There were also significant differences in recurrence-free survival based on biopsy GGG for the 1555 men who received radiation therapy (Fig. 1C). The 4-yr recurrence-free survival rates after radiation therapy were 95%, 91%, 85%, 78%, and 70% for GGG 1–5, respectively (p < 0.001, log rank test). On multivariable analysis with PSA and clinical stage, GGG was a significant independent predictor of BCR (Table 3).

In multivariable models adjusting for marital status, education, comorbidity, and hospital type in addition to PSA and clinical stage, GGG remained significantly associated with biochemical recurrence after both prostatectomy and radiation therapy (Supplementary Table 3). For men who underwent surgery, GGG was also significantly associated with BCR after adjusting for prostatectomy pathology (Supplementary Table 4). For men undergoing radiation therapy, GGG remained significant predictors of BCR after additional adjustment for hormonal therapy use (Supplementary Table 5).

Among the 4325 men who underwent RP, there were 36 (0.8%) deaths from prostate cancer and 193 (4.5%) deaths from other causes during follow-up. Of the 1555 men who had radiation therapy, 51 (3.3%) men died from prostate cancer and 118 (7.6%) died from other causes. Biopsy GGGs were significant predictors of prostate cancer death after RP and radiation therapy, as was prostatectomy GGG (all p≤0.001, log-rank).

Finally, we compared the concordance indices of GGG with a 3-tier and 4-tier classification system (Table 4). The new GGG system resulted in very virtually no change in predictive accuracy (improvement in concordance index by 0–0.02), compared with alternate classifications.

Table 4.

Concordance indices for different Gleason grade categorizations

| RP subset, biopsy Gleason | RP subset, prostatectomy Gleason | RT subset, biopsy Gleason | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorization | Univariable | Multivariablea | Univariable | Multivariablea | Univariable | Multivariablea |

| ≤6 vs 7 vs 8–10 | 0.593 | 0.658 | 0.640 | 0.771 | 0.675 | 0.738 |

| ≤6 vs 7 vs 8 vs 9–10 | 0.591 | 0.658 | 0.637 | 0.771 | 0.677 | 0.730 |

| ≤6 vs 3+4 vs 4+3 vs 8 vs 9 | ||||||

| 10 | 0.593 | 0.659 | 0.659 | 0.771 | 0.680 | 0.727 |

RP = radical prostatectomy; RT = radiotherapy.

Multivariable biopsy Gleason Cox models include preoperative prostate-specific antigen and clinical stage (T1 vs T2), and prostatectomy Gleason Cox model includes preoperative prostate-specific antigen, surgical margin status, and pathology stage (pT2 vs pT3a vs pT3b vs pT4). The concordance index has been corrected for optimism using 10-fold cross-validation.

4. Discussion

Using data in a population-based cohort from the NPCR of Sweden, we confirmed that the new GGGs predicted BCR after RP and radiation therapy. These findings support including GGG as part of the pathology report for prostate biopsy and RP, as suggested at the 2014 ISUP meeting.

One of the main reasons that this new system was proposed is to deal with the significant burden of prostate cancer overdiagnosis. Although use of active surveillance is increasing worldwide [7,8], a considerable proportion of low-risk men continue to undergo curative treatment. Some clinicians have suggested removing the label of “cancer” from Gleason score 6 disease as potential way to reduce overtreatment [9]. Although Gleason score 6 prostate cancer rarely metastasizes, it does have the ability to invade locally [10,11]. Moreover, since prostate biopsy samples a limited proportion of the prostate, more than a third of men diagnosed with Gleason score 6 disease on biopsy are subsequently upgraded upon resampling [12]. For example, our group previously reported that among Swedish men with clinically localized Gleason score 6 cancer on biopsy, approximately 50% had adverse pathology features at RP [13]. Consequently, there is a potential risk of misclassification by renaming Gleason score 6 as a noncancer. Epstein et al [3] suggested that men may incorrectly assume that a Gleason score 6 out of 10 is intermediate in aggressiveness and proposed a modification of the Gleason grading scale beginning at 1 in order to reduce overtreatment due to this erroneous assumption.

Another important feature of the new classification is separating Gleason scores 3+4 = 7 and 4+3 = 7 into different groups. Numerous previous studies have shown worse treatment outcomes in men with Gleason score 7 with primary pattern 4 versus 3. Moreover, from a clinical perspective some men with low-volume Gleason score 3+4 disease are managed with active surveillance, so to distinguish this from Gleason score 4+3 may also facilitate discussions at the point-of-care.

It is noteworthy that the recurrence-free survival for men in GGG 4 on biopsy was 77%, but merely 63% for men with GGG 4 assessed on the prostatectomy specimen. This discrepancy was due to the fact that the concordance between biopsy and prostatectomy grouping among was lowest for GGG 4. In men with GGG 4 cancer on biopsy a smaller proportion of biopsies were positive for cancer than for GGG 2, GGG 3 and GGG 5, and a larger proportion were downgraded to GGG 3 at prostatectomy. Overall, prostate cancer risk stratification is rapidly evolving, including increasing use of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging as well as several new genomic tissue tests [14,15]. Although tumor grade is merely one of several factors that forms the basis for management decisions, the new GGG present this information in a straightforward fashion and will be a cornerstone for treatment decisions in the foreseeable future. Although the new GGG system resulted in virtually no change in predictive accuracy compared with alternate classifications, the primary goal of adopting this system was not to improve predictive accuracy but rather to provide a simplified and user-friendly classification to aid in patient counseling.

This study has several limitations. Although our median follow-up of 4.6 yr was longer than the previous studies by Pierorazio et al [2] (2 yr) and Epstein et al [3] (3 yr), it was insufficient to evaluate important endpoints such as development of metastasis and prostate cancer death. In all three studies, the limited follow-up was primarily due to excluding cases diagnosed before the 2005 ISUP meeting. Future studies are needed to confirm the utility of the GGGs with long-term oncologic endpoints; however, given our results, it seems unlikely that that the GGGs would be less accurate in prediction of long-term outcome than previously used classifications. Another limitation of our study is that the NPCR follow-up study only included men with PSA < 20 ng/ml.

Correspondingly, very few men had lymph node metastases and there were too few men with GGG 5 to compare the 5-tier system with a 6-tiered system with separation of Gleason 9 and 10. It was also not possible to clearly distinguish adjuvant and salvage therapy in our dataset. In addition, the Gleason grade assessment in our analysis was made by pathologists across Sweden without central review, which is one potential explanation for the lower concordance-indices using GGG in our real-world setting compared with the previous study by Epstein et al [3] which was restricted to academic centers of excellence. Although substantial efforts have been made to standardize Gleason grading across Sweden [16], we cannot confirm that all pathologists had adopted the ISUP 2005 changes at study inception and the large number of pathologists that assigned grade decreased the predictive precision. Since the only other data on GGG to date are from academic centers of excellence, we believe that the multi-center assessment of grading is in fact a strength as it validates the utility of the new GGGs in a population-based, real-world setting and additional adjustment for hospital type did not change the results. Another strength of the study was the uniform follow-up assessment of BCR by chart review at 5 yr after diagnosis.

5. Conclusion

This nationwide, population-based cohort show the ability of the simplified, user-friendly GGGs to predict BCR after RP and radiation therapy with virtually no change in predictive accuracy compared with previous classifications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: The Swedish Research Council 825-2012-5047 and The Swedish Cancer Foundation 11 0471, Västerbotten County Council, and Lion’s Cancer Research Foundation at Umeå University. Loeb is supported by the New York University Cancer Institute (P30 CA016087), the Louis Feil Charitable Lead Trust, and the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K07CA178258. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Yasin Folkvaljon had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Loeb, Egevad, Stattin.

Acquisition of data: Robinson, Lissbrant, Egevad, Stattin.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Loeb, Folkvaljon, Stattin.

Drafting of the manuscript: Loeb, Folkvaljon, Egevad, Stattin.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Loeb, Egevad, Stattin, Robinson, Lissbrant, Folkvaljon.

Statistical analysis: Folkvaljon.

Obtaining funding: Loeb, Stattin.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Stattin.

Supervision: Stattin.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Stacy Loeb certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Loeb: Bayer (advisory board, honorarium for lecture), Sanofi (reimbursed travel to PCF meeting). Stattin: Ferring (participation in an advisory meeting) and Astra Zeneca (honorarium lectures).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carter HB, Partin AW, Walsh PC, et al. Gleason score 6 adenocarcinoma: should it be labeled as cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4294–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierorazio PM, Walsh PC, Partin AW, Epstein JI. Prognostic Gleason grade grouping: data based on the modified Gleason scoring system. BJU Int. 2013;111:753–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein JI, Zelefsky MJ, Sjoberg DD, et al. A contemporary prostate cancer grading system: A validated alternative to Gleason score. Eur Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.046. In press. http://dx.doi.org/101016/jeururo201506046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Van Hemelrijck M, Wigertz A, Sandin F, et al. Cohort profile: The National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden and Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden 2. 0. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:956–67. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Prostate Cancer Register Sweden. www.npcr.se

- 6.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228–42. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loeb S, Berglund A, Stattin P. Population based study of use and determinants of active surveillance and watchful waiting for low and intermediate risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1742–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Womble PR, Montie JE, Ye Z, et al. Contemporary use of initial active surveillance among men in michigan with low-risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;67:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sartor O, Loriaux DL. The emotional burden of low-risk prostate cancer: proposal for a change in nomenclature. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2006;5:16–7. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2006.n.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haffner MC, Mosbruger T, Esopi DM, et al. Tracking the clonal origin of lethal prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4918–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI70354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berman DM, Epstein JI. When is prostate cancer really cancer? Urol Clin North Am. 2014;21:339–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro RH, Johnstone PA. Risk of Gleason grade inaccuracies in prostate cancer patients eligible for active surveillance. Urology. 2012;80:661–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vellekoop A, Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Stattin P. Population based study of predictors of adverse pathology among candidates for active surveillance with gleason 6 prostate cancer. J Urol. 2014;191:350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein EA, Yousefi K, Haddad Z, et al. A genomic classifier improves prediction of metastatic disease within 5 years after surgery in node-negative high-risk prostate cancer patients managed by radical prostatectomy without adjuvant therapy. Eur Urol. 2015;67:778–86. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence EM, Gnanapragasam VJ, Priest AN, Sala E. The emerging role of diffusion-weighted MRI in prostate cancer management. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:94–101. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egevad L. Reproducibility of Gleason grading of prostate cancer can be improved by the use of reference images. Urology. 2001;57:291–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00922-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.