Abstract

LAY ABSTRACT

Autism research indicates that there may be similar brain circuits affected in both individuals with autism and individuals with mood disorders such as major depression. However, psychotropic medications, while widely prescribed in individuals with autism, have been largely unsuccessful in treating core autism symptoms, indicating that etiology of co-existing psychiatric and autism symptoms may differ.

In this fMRI study, the relationship between brain activity in the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure located deep within the brain, and activity in other parts of the brain were examined in 25 individuals with autism and 28 individuals without autism, during rest. This study provides the first evidence that connections between the amygdala and other brain regions are not uniformly atypical in autism, but differ depending on the subregion under investigation. In autism we observed weaker connections from the laterobasal subregion of the amygdala, a group of nuclei involved in social behavior and emotion, and, stronger connections from the centromedial and superficial subregions, which are involved in emotional arousal and olfaction. Additionally, we found that connectivity patterns related to autism symptoms were different from connectivity patterns related to mood symptoms. This finding suggests that despite occurring frequently in individuals with autism, mood disorders may involve separate neural mechanisms. This finding may also help explain why psychotropic medications are generally ineffective at treating autism symptoms.

SCIENTIFIC ABSTRACT

Background

The amygdala is a complex structure with distinct subregions and dissociable functional networks. The laterobasal subregion of the amygdala is hypothesized to mediate the presentation and severity of autism symptoms, although very little data are available regarding amygdala dysfunction at the subregional level.

Methods

In this study, we investigated the relationship between abnormal amygdalar intrinsic connectivity, autism symptom severity, and anxiety and depressive symptoms. We collected resting state fMRI data on 31 high functioning adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder and 38 typically developing (TD) controls aged 14–45. 25 participants with ASD and 28 TD participants were included in the final analyses. ASD participants were administered the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Adult participants were administered the Beck Depression Inventory II and the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Functional connectivity analyses were conducted from three amygdalar subregions: centromedial (CM), laterobasal (LB) and superficial (SF). In addition, correlations with the behavioral measures were tested in the adult participants.

Results

In general, the ASD group showed significantly decreased connectivity from the LB subregion and increased connectivity from the CM and SF subregions compared to the TD group. We found evidence that social symptoms are primarily associated with under-connectivity from the LB subregion whereas over-connectivity and under-connectivity from the CM, SF and LB subregions are related to co-morbid depression and anxiety in ASD, in brain regions that were distinct from those associated with social dysfunction, and in different patterns than were observed in mildly symptomatic TD participants.

Conclusions

Our findings provide new evidence for functional subregional differences in amygdala pathophysiology in ASD.

Keywords: autism, amygdala, resting state fMRI, laterobasal, superficial, centromedial, depression, anxiety

INTRODUCTION

Core deficits of ASD involve impaired social-communication and restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association 2013) that persist throughout the lifespan and diagnostically differentiate ASD from other neurodevelopmental disorders. Beyond core ASD symptoms, evidence suggests that ASD is also characterized by broad impairments in emotional expression and regulation (Mazefsky, Borue, Day, & Minshew, 2014) and higher than expected rates of comorbid depression and anxiety (Kim, Szatmari, Bryson, Streiner, & Wilson, 2000; Mazefsky, Folstein, & Lainhart, 2008; Richey et al., 2015; Sterling, Dawson, Estes, & Greenson, 2008). Multiple brain systems are likely affected in ASD, however, converging evidence from structural, biochemical, functional, and post-mortem studies indicates that amygdalar abnormalities are fundamentally involved. Given the key role that the amygdala plays in domains impaired in ASD such as social cognition, processing and regulating emotions, and evaluating the social value of stimuli (Bzdok, Laird, Zilles, Fox, & Eickhoff, 2013), obtaining a greater understanding of amygdalar abnormalities in ASD and their relation to behavioral symptoms may be critical to identifying the pathophysiology of ASD and associated psychiatric comorbidities.

Very limited information is available on how subregions of the amygdala are differentially affected in individuals with ASD or how regionally specific abnormalities are related to core autism symptoms and mood symptoms. Most reports, including previous work by our group (Kleinhans et al., 2009; Kleinhans et al., 2011; Kleinhans et al., 2008), evaluated the amygdala as a unitary structure despite its complex anatomy and multiple functions (Sah, Faber, Lopez De Armentia, & Power, 2003). The amygdala has numerous, diverse nuclei and dense connectivity to cortical and subcortical brain regions. In addition to social cognition, the amygdala is involved in other functions, including pain, motivation, learning and memory, anxiety, depression and sensory processing (Sah et al., 2003). A volumetric study by our group found that the LB subregion specifically was enlarged in children with ASD, and that the degree of LB enlargement correlated with social and communication skills (Kim et al., 2010). A postmortem study reported evidence that the lateral nucleus of the amygdala, which is crucial for socioemotional processing, is the most consistently impacted in ASD (Schumann & Amaral, 2006). However, neuronal abnormalities were reported in all subregions to varying degrees, raising the possibility that individual differences in clinical severity and behavioral subtypes may be linked to abnormalities in specific amygdalar subregions and connectivity patterns.

The relationship between subregional amygdalar pathophysiology and depression and anxiety symptoms in ASD has been understudied, although we previously reported that greater social anxiety was associated with increased activation in the right amygdala and left middle temporal gyrus, and decreased activation in the fusiform face area (Kleinhans et al., 2010). Studies of individuals with primary diagnoses of mood disorders indicate that the neural substrates of anxiety and depression share many of the same limbic and social brain abnormalities (Drevets, Price, & Furey, 2008) that have been linked to ASD symptoms. However, psychotropic medications, while widely prescribed (Esbensen, Greenberg, Seltzer, & Aman, 2009; Mandell et al., 2008), have been largely unsuccessful in treating core autism symptoms (Siegel & Beaulieu, 2012), suggesting that etiology of co-morbid psychiatric symptoms and autism symptoms may differ.

The main goal of this study was to determine whether individuals with ASD showed subregional differences in intrinsic functional connectivity within the amygdala subregions compared to typically developing individuals, and to link aberrant connectivity to symptom profiles of core ASD deficits, depression and anxiety. Functional connectivity of large scale networks in ASD has been broadly studied. Although initial reports overwhelmingly described reduced connectivity in ASD (Muller, 2007; Muller et al., 2011), more recent work has demonstrated that ASD is characterized by both over connectivity and under connectivity (Di Martino et al., 2014; Venkataraman, Duncan, Yang, & Pelphrey, 2015) and a higher degree of interaction between cortical and subcortical networks than is observed in typically developing individuals (Cerliani et al., 2015). However, amygdala subregions are rarely used as seed point in studies of intrinsic connectivity and little to no information is available on large-scale differences between individuals with ASD and typically developing peers. To comprehensively examine amygdala connectivity, amygdalar subregions were segmented with the parcellation approach developed by Amunts and colleagues (2005): the centromedial subregion (CM), the laterobasal subregion (LB), and the superficial subregion (SF). We used linear regression explore the association between symptoms of autism, anxiety, and depression and functional connectivity in individuals with and without ASD. Previous work in the animal and human literature suggests that these subregions are functionally distinct with different anatomical connections. The CM subregion has been strongly associated with anxiety (Grijalva, Levin, Morgan, Roland, & Martin, 1990; Oler et al., 2010), the LB subregion has been associated with core autism symptoms(Kim et al., 2010), social and sensory processing (Sah et al., 2003), and depression (Rubinow et al., 2014), and the SF subregion has been associated with olfaction (Sah et al., 2003) and social information processing including reward related information (Bzdok et al., 2013). Consistent with previous work on amygdala subregions in ASD (Kim et al., 2010; Schumann & Amaral, 2006) and known anatomical connectivity (Sah et al., 2003), we predicted that atypical connectivity in ASD would be observed between the LB subregion and the orbital frontal cortex and prefrontal cortex, based on the role these brain regions play in regulating emotion (Banks, Eddy, Angstadt, Nathan, & Phan, 2007), as well as for the superior temporal gyrus, reflecting its role in social cognition, and for the nucleus accumbens which has a putative role in reduced social motivation in ASD (Assaf et al., 2013; Birn, Diamond, Smith, & Bandettini, 2006). In addition, we predicted that more severe levels of social impairment and depression would be associated with reduced connectivity from the LB subregion to these areas. We also hypothesized that SF connectivity to limbic structures would be associated with core autism symptoms, and reduced connectivity between the CM and the prefrontal cortex would be associated with increased anxiety in ASD.

METHODS

Participants

Thirty-one adolescents and adults with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and 37 typically developing (TD) controls matched on age, gender, motion, and IQ participated in the fMRI protocol. Fifteen participants were excluded from further analysis because of scanner artifacts (3 ASD, 5 TD), an incidental finding on MRI (1 TD), and excessive motion (3 ASD, 3 TD). All participants had FSIQ and VIQ≥80. ASD diagnoses were confirmed with the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised™, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule™, and clinical judgment based on all available information and DSM-IV criteria. Eight ASD participants reported taking psychotropic medication on the day of the scan (clonidine, topiramate, fluoxetine, lorazepam, bupropion XL, methylphenidate, sertraline, citalopram, gabapentin, adderall, oxcarbazepine). Current levels of anxiety and depression were assessed in our adult participants using a standard administration of the Beck Depression Inventory–II™ (BDI-II) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory™ (BAI). General intelligence was assessed using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence™ (WASI) and the Differential Abilities Scale™ (DAS). Clinical and demographic information is reported in Table 1. During a semi-structured interview, TD participants were screened and excluded for current and past psychiatric disorders, history of a developmental learning disability, and contraindications to MR imaging. TD participants were not excluded on the basis of the BDI-II or BAI.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| ASD (n=25)1 | TD (n = 28)2 | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | ||

| Age | 22.53 | (5.98) | 25.57 | (8.99) | .166 |

| Full scale IQ3 | 110.28 | (12.31) | 111.71 | (10.86) | .660 |

| Verbal IQ3 | 106.24 | (17.75) | 111.57 | (11.29) | .202 |

| Performance IQ3 | 111.12 | (10.35) | 108.89 | (11.73) | .478 |

| Beck Depression Inventory4 | 11.22 | (9.63) | 4.18 | (4.22) | .004 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory4 | 9.50 | (7.88) | 3.55 | (3.51) | .003 |

| ADOS subscales | |||||

| Communication | 2.60 | (1.50) | |||

| Social | 5.44 | (1.96) | |||

| ADI-R subscales | |||||

| Communication | 14.68 | (5.64) | |||

| Social | 18.72 | (4.03) | |||

| Repetitive Behavior | 5.40 | (2.22) | |||

Note.

nine females,

six females,

adults only

IQ = Intelligence Quotient, ADOS= Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, ADI-R= Autism Diagnostic Interview - Revised

Based on Differential Abilities Scale for participants age 13–17 and the WASI for participants age 18–40

ADOS = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule

ADI-R = Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised

This study was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Informed written consent was obtained from all study participants.

Procedure

fMRI Data Acquisition

Structural and functional MRIs were collected on a 3T Phillips Achieva MR system (version 1.5, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) with dual Quasar gradients using an 8-channel SENSE head coil. A T1-weighted MPRAGE (magnetization prepared-rapid gradient echo; TR=7.7 ms; TE=3.7 ms; flip angle=8; FOV=220 mm; matrix 200×200; 180 slices; acquisition voxel size (mm)=1.00/1.00/1.00; reconstruction voxel size (mm) 0.86/0.86/1.00; TFE shots=144; TFE durations=1633.0; Inversion delay (TI) 823.8 ms; slice orientation axial, foldover direction RL; REST slab 57.1 mm slice thickness) was collected for co-registration and anatomical localization. Whole-brain T2*-weighted images were acquired using a single-shot gradient-recalled echo planer imaging (EPI) sequence (TR=2000 ms; TE=21 ms; flip angle=76°; FOV=220 mm) with a matrix size of 64×64 (in-plane resolution=3.4375×3.4375 mm). Thirty-eight axial slices (slice thickness=3.5 mm, 0 mm gap) were acquired per volume. Five dummy scans followed by 200 volumes were collected. Participants were instructed “close your eyes, relax, and let your mind wander.” The B0 field map was acquired using a fast field echo sequence (TR=200 ms; TE1=4.6 ms; TE2=5.6 ms; flip angle=30°; FOV=220 mm) with a matrix size of 64×64 (in-plane resolution=3.44×3.44 mm, slice thickness = 3.5mm, 0 mm gap). Scan duration=53 s. The B0 field map was reconstructed by subtracting the phase images from the two TE image acquisitions. The output contained a magnitude map and a B0 map.

Physiological Monitoring

Physiological monitoring data were collected to examine and control for low-frequency cardiac and respiratory contamination and possible aliasing on the BOLD functional connectivity analyses (Birn et al., 2006; Shmueli et al., 2007). A pulse-oximeter placed on the left hand index finger and a respiratory belt was placed around the chest. These devices were implemented with a sampling rate of 500 Hz and provide a pulsed output for each heartbeat and a scaled respiratory waveform. Data were recorded using LabVIEW™.

fMRI Processing and Statistical Analysis

FMRI data preprocessing was performed using the FMRIB Software Library version 4.1.7 (FSL; http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/) and Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI; http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/). Our preprocessing pipeline consisted of 1) artifact denoising using MELODIC 2) motion correction in conjunction with brain extraction and B0 unwarping with FUGUE 3) removal of spike artifacts using 3dDespike 4) physiological correction using 3dRETROICOR (Glover, Li, & Ress, 2000) or by filtering out the signal from the cerebral spinal fluid when physiological data were unusable 5) filtering motion parameters and single point motion regressors (Lemieux, Salek-Haddadi, Lund, Laufs, & Carmichael, 2007) when the frame-to-frame displacement exceeded .5 mm or .5 degrees on any axis 6) temporal high-pass filter of sigma=100 s and 7) spatial smoothing (FWHM=5 mm).

Seed point times series extraction

Parcellation of the amygdala was based on the Julich histological atlas (Amunts et al., 2005), which segments the amygdala into three subregions: CM subregion, the LB subregion, and the SF subregion. Timeseries were extracted from the right and left LB, CM, and SF subregions of the amygdala according to previously published studies (Roy et al., 2013). Amygdala sub-regions were defined using probabilistic maps of cytoarchitectonic boundaries (Amunts et al., 2005). Amygdala sub-region masks were defined in standard space using a 50% probability threshold then warped into native space. Each amygdala voxel was assigned to one subregion (LB, CM, or SF) and the mean time series were extracted by averaging across all voxels within each subregion.

Statistical processing

Time series analyses were carried out using FMRIB’s Improved Linear Model (FILM) with local autocorrelation correction. For the right and left amygdala, all of the time series (LB, CM, and SF) were simultaneously included in the first-level model. Statistical effects were estimated at each voxel for each subregion (LB, CM, SF; right and left hemispheres separately). Individual FMRI data were registered to the high resolution MPRAGE and then warped to the MNI152 standard image with an affine transformation using FLIRT (FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool) and resampled to 2 mm3 voxels. No between-group differences in the root mean square of the motion parameters were present: TD=0.28 (0.26), ASD=0.33 (0.2); p = .42; range of motion for ASD = (0.09–0.89) and for TD = (0.10–1.49).

Analysis of group-wise effects were conducted using FLAME (FMRIB’s Local Analysis of Mixed Effects), a mixed-effects method. Statistical corrections for multiple comparisons were conducted by using cluster-thresholding based on Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling set at z>2.3 (voxel height) and p<.05 (cluster extent), ROI or whole brain volume corrected. In addition to the whole brain analyses, we employed an ROI approach to test for connectivity differences in the right and left nucleus accumbens because these structures are small relative to the whole brain. The nucleus accumbens masks were obtained from Harvard-Oxford Subcortical Structural Atlas (Desikan et al., 2006).

RESULTS

Depression and Anxiety Measures

Independent t-tests were conducted on the BDI-II and the BAI data. The ASD group had significantly greater symptoms of anxiety (p=.003) and depression (p=.004) than the TD group. Three ASD participants reported mild depression, two reported moderate depression, one reported severe depression, nine reported mild anxiety, one reported moderate anxiety and one reported severe anxiety. In addition, two included TD individuals reported symptoms consistent with mild anxiety and one individual reported symptoms consistent with mild depression. (see Table 1)

fMRI Between Group Comparisons

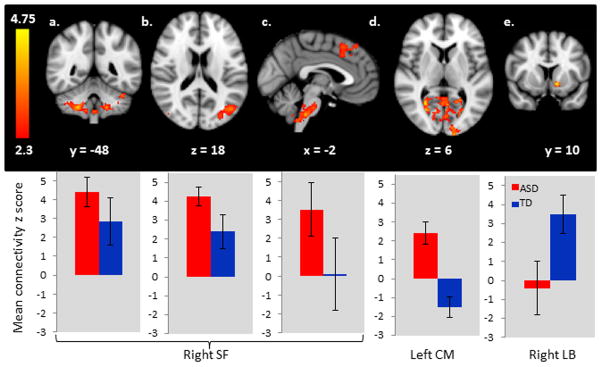

Comprehensive results of the between-group comparisons are reported in Table 2 and Figure 1. The ASD group showed reduced connectivity between the LB amygdala and the nucleus accumbens and increased connectivity between the CM subregion and the occipital cortex and between the SF amygdala and the cerebellum, occipital cortex, inferior temporal lobes, prefrontal cortex and brain stem. In order to investigate whether medication was driving the reported group-differences, post-hoc, we separated the ASD group into medicated and unmedicated subgroups and looked at subgroup means within the significant clusters. We found that medicated participants with ASD were either indistinguishable from the ASD participants without medication, or had connectivity patterns that were different, in the direction of being more similar to the TD participants. Thus, overall, our data indicates that psychotropic medication may attenuate group differences. See supplementary figure 1 for these results.

Table 2.

Group differences in intrinsic connectivity

| seed | contrast | R/L | Peak Region | voxels | p value | z-max | MNI (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| L CM | ASD>TD | L | occipital pole | 1316 | .0000 | 3.72 | −18 | −98 | 0 |

| R,L | (lingual gyrus, intracalcarine) | ||||||||

| R LB | TD>ASD | L | nucleus accumbens1 (putamen, caudate) | 47 | .0359 | 3.63 | −12 | 10 | −8 |

| R SF | ASD>TD | R | VIIIb (pons, medulla, VIIIa, Vllla) | 1705 | .0000 | 4.46 | 24 | −46 | −48 |

| R | occipital fusiform gyrus (lateral occipital cortex, crus I, occipital pole) | 546 | .0052 | 3.48 | 30 | −86 | −20 | ||

| R | frontal pole (superior frontal gyrus, paracingulate gyrus) | 437 | .0196 | 3.32 | 8 | 38 | 60 | ||

| L | lateral occipital cortex (crus I, occipital pole) | 445 | .0177 | 3.4 | −44 | −70 | 16 | ||

| L | lateral occipital cortex, inferior division | 407 | .0293 | 3.49 | −46 | −78 | −22 | ||

Note. R = right, L = left. CM = centromedial, LB = laterobasal, SF = superficial. Regions are labeled using the Harvard-Oxford Cortical Structural Atlas, the Harvard-Oxford Subcortical Structural Atlas, and the Probabilistic Cerebellar Atlas according to the peak p value within a contiguous cluster. Regions listed in parentheses were additional regions within the significant cluster.

Region of interest analysis. Unless noted, p-values are based on a whole-brain cluster correction for multiple comparisons.

Figure 1.

Areas of abnormal intrinsic functional connectivity in ASD. Panels a–c show increased connectivity in ASD from the right superficial subregion of the amygdala to the cerebellum, lateral occipital cortex, brainstem, and superior frontal gyrus. Panel d shows increased connectivity in ASD from the left centromedial subregion to the occipital pole and panel e shows decreased connectivity in ASD from the right laterobasal subregion to the nucleus accumbens. The bar charts depict group means and standard deviations for the significant clusters shown in the upper panel. Data are presented in radiological orientation (R=L). See Table 2 for detailed results.

fMRI Correlations with diagnostic measures

Correlational analyses were conducted on the ASD group only. Correlational analyses were conducted on the adults only to maintain a consistent sample with the anxiety and depression correlations for comparison purposes. (Participants under the age of 18 were not administered the BDI-II or BAI.)

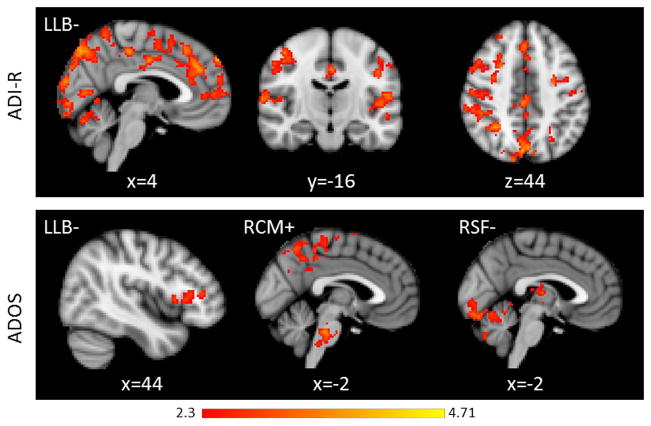

ADI-R

Reduced connectivity from the LB subregion to the cingulate gyrus, bilateral prefrontal cortex, superior temporal gyrus, and cerebellar vermis was associated with higher scores on the ADI-R social subscale. See Table 3 and Figure 2 for detailed results.

Table 3.

Correlations between intrinsic amygdala connectivity and early developmental social impairment

| seed region | +/− | R/L | region | voxels | p value | z-max | MNI (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| L LB | - | L | supracalcarine cortex (cingulate gyrus, posterior division, inferior frontal gyrus, pars opercularis, intracalcarine cortex, lateral occipital cortex, inferior division, lateral occipital cortex, superior division, lingual gyrus, occipital fusiform gyrus, occipital pole, precuneous cortex, superior parietal lobule, parietal operculum, angular gyrus, central opercular cortex, frontal pole, heschl’s gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, pars triangularis, middle frontal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, temporooccipital part, planum temporale, superior temporal gyrus, posterior division, supramarginal gyrus, anterior division, supramarginal gyrus, posterior division, vermis VI, VI, Crus I) | 13462 | .0000 | 4.34 | −4 | −88 | −10 |

| L LB | - | R | frontal pole (superior frontal gyrus, paracingulate gyrus, juxtapositional lobule cortex, cingulate gyrus, anterior division, inferior frontal gyrus, pars triangularis) | 2903 | .0000 | 3.99 | 4 | 58 | 38 |

| L LB | - | L | superior temporal gyrus, posterior division (supramarginal gyrus, anterior division, supramarginal gyrus, posterior division, planum temporale, middle temporal gyrus, posterior division, middle temporal gyrus, temporooccipital part, inferior temporal gyrus, temporooccipital part, heschl’s gyrus, angular gyrus, central opercular cortex) | 2011 | .0000 | 4.16 | −64 | −42 | 14 |

| L LB | - | L | inferior frontal gyrus, pars opercularis (middle frontal gyrus, precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus) | 998 | .0000 | 3.88 | −58 | 14 | 16 |

Note. R = right, L = left. LB = laterobasal. Regions are labeled using the Harvard-Oxford Cortical Structural Atlas, the Harvard-Oxford Subcortical Structural Atlas, and the Probabilistic Cerebellar Atlas according to the peak p value within a contiguous cluster. Regions listed in parentheses were additional regions within the significant cluster. P-values are based on a whole-brain cluster correction for multiple comparisons.

Figure 2.

Relationship between intrinsic amygdala connectivity and social impairment (top row = ADI-R Social Score, bottom row = ADOS social score) in the ASD group. Data are presented in radiological orientation (R=L). All clusters depicted on the figure were significant at p < .05, whole brain cluster threshold corrected. The relationship between reduced connectivity from the LB region and greater social impairment was observed from both measures. Current social dysfunction, measure by the ADOS, was also correlated with increased connectivity from the CM subregion and decreased connectivity from the SF subregion. See Tables 3 and 4 for detailed results.

ADOS

Higher social impairment was associated with increased connectivity from the left and right CM subregion, and decreased connectivity from the left LB to the inferior frontal gyrus and right SF subregion to the thalamus, cerebellum, and occipital cortex. See Table 4 and Figure 2 for detailed results.

Table 4.

Correlations between intrinsic amygdala connectivity and current social impairment

| seed region | +/− | R/L | region | voxels | p value | z-max | MNI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| L CM | + | R | precuneous cortex | 503 | .0027 | 3.68 | 10 | −46 | 58 |

| R | (precentral gyrus, superior parietal lobule, postcentral gyrus) | ||||||||

| R CM | + | precuneous cortex (cingulate gyrus, posterior division, temporal occipital fusiform cortex, lateral occipital cortex, inferior division, lateral occipital cortex, superior division, occipital pole) | 2524 | .0000 | 3.90 | −10 | −52 | 44 | |

| R CM | + | R | crus II | 1449 | .0000 | 3.67 | 36 | −78 | 38 |

| R CM | + | L | lateraloccipital cortex, inferior division | 657 | .0003 | 3.75 | −46 | −68 | −16 |

| L | (precuneous cortex, lateral occipital cortex, superior division, cingulate gyrus, posterior division, middle temporal gyrus, temporooccipital part, precentral gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, temporooccipital part) | ||||||||

| R CM | + | R | superior frontal gyrus (precentral gyrus, juxtapositional lobule cortex) | 462 | .0044 | 3.35 | 12 | 4 | 64 |

| R CM | + | R | brain stem | 414 | .0090 | 4.00 | 2 | −30 | −32 |

| R CM | + | R | frontal pole | 325 | .0360 | 3.40 | 32 | 60 | 16 |

| R CM | + | R | inferior temporal gyrus, temporooccipital part | 314 | .0430 | 3.91 | 54 | −52 | −24 |

| L LB | - | R | frontal operculum cortex | 358 | .0363 | 3.69 | 36 | 26 | 8 |

| R | (frontal pole, inferior frontal gyrus, pars triangularis) | ||||||||

| R SF | - | L | crus I | 2674 | .0000 | 4.71 | −52 | −68 | −32 |

| L | (crus II, I–IV, V, VI, VIIb, VIIIa, VIIIb, vermis VI, vermis VIIIa) | ||||||||

| R SF | - | L | cingulate gyrus, posterior division | 873 | .0001 | 4.03 | −8 | −38 | 6 |

| R,L | (thalamus) | ||||||||

| R SF | - | R | middle temporal gyrus, posterior division | 668 | .0012 | 4.05 | 60 | −24 | −20 |

| R | (middle temporal gyrus, anterior division, inferior temporal gyrus, posterior division, superior temporal gyrus, anterior division, inferior temporal gyrus, temporooccipital part) | ||||||||

| R SF | - | R | crus II | 475 | .0117 | 3.54 | 28 | −88 | −42 |

| R | (crus I,I–IV,V,VI) | ||||||||

| R | (occipital pole, lingual gyrus, lateral occipital cortex, inferior division, occipital fusiform gyrus) | ||||||||

Note. R = right, L = left. CM = centromedial, LB = laterobasal, SF = superficial. Regions are labeled using the Harvard-Oxford Cortical Structural Atlas, the Harvard-Oxford Subcortical Structural Atlas, and the Probabilistic Cerebellar Atlas according to the peak p value within a contiguous cluster. Regions listed in parentheses were additional regions within the significant cluster. P-values are based on a whole-brain cluster correction for multiple comparisons.

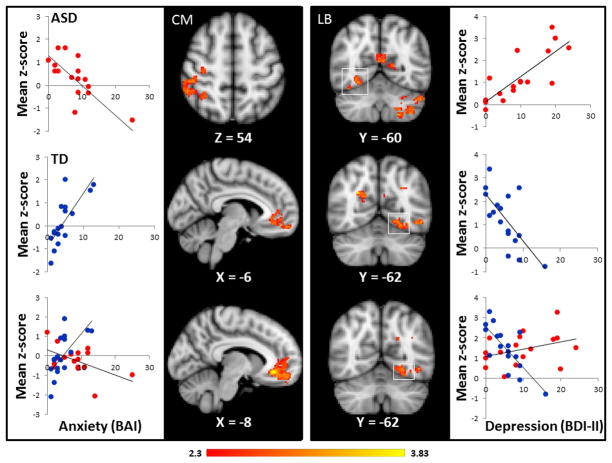

fMRI Correlations with depression and anxiety measures

One participant with ASD was a major outlier in all analyses (because of severe anxiety and depression) and was excluded from the correlational analyses. In addition, results that contained one or more major outlier, identified using stem-and-leaf plots in PASW Statistics 18, were not reported.

Correlations in ASD group

Higher levels of anxiety, as measured with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), were associated with reduced right SF– left superior temporal gyrus connectivity and increased right SF–left temporal pole and right SF- hypothalamic connectivity. Higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory –II (BDI-II) were correlated with higher connectivity between the LB subregion and the insular cortex and SF subregion and the parahippocampal gyrus, thalamus, hypothalamus, and the midbrain. Decreased connectivity was observed between the LB and the cerebellum and SF and the planum temporale. See Supplementary Table 5 for detailed results.

Correlations in TD group

Higher scores on the BAI were positively correlated with connectivity from the CM to the frontal, cerebellar and temporal lobe regions and negatively correlated with connectivity from the right LB to the cerebellum, precuneous, brain stem, temporal pole and occipital cortex, and from the SF to the precuneous, cingulate gyrus, paracingulate gyrus, lateral occipital cortex, and middle frontal gyrus. Higher scores on the BDI-II were negatively correlated with the CM subregion and occipital cortex, cingulate gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, and the temporal pole, and from the LB subregion to the occipital cortex and paracingulate cortex, and positively correlated with the SF subregion to the parahippocampal gyrus, subcallosal gyrus, and the occipital cortex. See Supplementary Table 6 for detailed results.

Group by measure interaction effect

We tested whether the relationship between the BDI-II and BAI and connectivity was dependent on group and we found numerous significant interaction effects. For the BAI, a significant interaction effect was found between the CM subregion and the paracingulate gyrus and supramarginal gyrus (see Figure 3), the right LB subregion and the cerebellum, occipital cortex, and the medial temporal lobe, and the SF subregion and the precuneous, middle temporal gyrus, insular cortex, occipital cortex, and the cerebellum. Interaction effects with the BDI-II were found between the right CM subregion and the occipital cortex, cerebellum, superior parietal lobule, and the brain stem, the LB subregion and the precuneous, occipital cortex, postcentral gyrus, and the cerebellum, and the SF subregion and the prefrontal cortex. See Supplementary Table 7 for additional details.

Figure 3.

Relationship between depression (BDI, right side) and anxiety (BAI, left side) in the ASD and TD groups. Group by measure interaction effects were presented in the bottom row. Data are presented in radiological orientation (R=L). Clusters signify brain regions showing a significant (p < .05, whole brain corrected) correlation or interaction effect. Scatter plots depicting the relationship between mood symptoms and amygdala connectivity are provided for descriptive purposes. TD participants are labeled in blue, ASD participants are labeled in red. For each subject, a mean z-score was obtained by averaging the z-score of all voxels for that participant within the mask, which was defined by a significant cluster on the regression analyses or the interaction analyses (see Supplementary Table 7).

DISCUSSION

Intrinsic connectivity and core social dysfunction in ASD

Our study investigated intrinsic functional connectivity of amygdala subregions in high functioning ASD. Overall, several notable atypical connectivity patterns emerged from this study. First, consistent with previously reported reduced numbers of neurons in the lateral nuclei of the amygdala (Schumann & Amaral, 2006), our study demonstrated that reduced intrinsic connectivity at the group level in ASD was only observed from the LB subregion, which is involved in evaluating the emotional significance of all stimuli including social signals (Mosher, Zimmerman, & Gothard, 2010). Compared to the TD group, our participants with ASD showed reduced intrinsic connectivity between the LB subregion and the nucleus accumbens. This result is consistent with a fundamental impairment in the neural circuitry supporting social motivation (Dawson, Webb, & McPartland, 2005) in individuals with ASD. In addition, the correlations between the ADI-R social score, which probes the early development of social symptoms in ASD, and amygdala connectivity were limited to the LB subregion and showed a negative relationship, indicating that more severe social impairment was associated with reduced connectivity. The brain regions that were sensitive to individual differences in the ADI-R suggest that more severely affected individuals have poorer connectivity between the LB amygdala and cortical regions involved in self-referential thought, inhibition, mood regulation, cognitive control, social cognition, attention, and sensory processing. The regions that were sensitive to the relationship between connectivity and the ADOS social score were more limited than the ADI-R and somewhat inconsistent with the brain regions that were sensitive to between-group differences. Instead, individuals with the most severe current social dysfunction showed lower connectivity between the LB amygdala and the inferior frontal gyrus, a region involved in externally-directed cognition, and increased connectivity between the CM amygdala and brain stem and primary motor-sensory regions, suggesting the presence of higher autonomic arousal.

Our study builds upon a growing body of evidence demonstrating that abnormal social brain circuitry is a critical etiological mechanism associated with ASD and provides physiological evidence that reward circuitry is aberrant in ASD. Available data imply that a collusion of brain and experiential mechanisms result in aberrant neurodevelopment and social dysfunction in ASD (Dawson, 2008). The emergence of social dysfunction may develop as a consequence of a failure of individuals with autism to find faces rewarding, which results in an impoverished social environment during critical developmental periods. For example, recent evidence shows that infants who eventually develop autism show a decline between 2 and 6 months of age in attention to the eyes, which has a key role directing typical social development. The etiological mechanism for this reduced drive to interact with people or look at faces is poorly understood. However, several lines of evidence suggest that the amygdala, nucleus accumbens, orbital frontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) support reward processing in TD individuals, and evidence is building that these brain regions are abnormal in ASD (Delmonte, Gallagher, O’Hanlon, McGrath, & Balsters, 2013; Schmitz et al., 2008; Scott-Van Zeeland, Dapretto, Ghahremani, Poldrack, & Bookheimer, 2010). This study demonstrated reduced intrinsic functional connectivity between the LB amygdala and nucleus accumbens, two brain regions intimately involved in reward processing with direct, anatomical projections (McDonald, 1991; Sah et al., 2003). In addition, we found that reduced LB-ACC and reduced LB-inferior frontal cortex were correlated with more severe developmental history of social dysfunction. As such, our data indicates that abnormalities in the intrinsic neural circuitry underlying social cognition and reward processing may contribute to the persistence of social impairment in high functioning adolescents and adults despite intact intellectual functioning.

In contrast, increased connectivity in ASD was observed from the CM, a subregion involved in allocating attention to important stimuli and initiating appropriate autonomic responses, to primary visual and visual association areas. This is notable given that prior research has reported increased activation in visual cortex during visual and language tasks (Gaffrey et al., 2007; Kana et al., 2013; Keehn, Brenner, Palmer, Lincoln, & Muller, 2008; Kleinhans et al., 2010; Sahyoun, Belliveau, Soulieres, Schwartz, & Mody, 2010), and suggests that heightened arousal related to the CM amygdala may play a role in atypically enhanced recruitment of visual cortex during task performance in ASD. Higher connectivity between the CM and the brainstem was also correlated with more severe levels of current social dysfunction. Although sensory symptoms were not explicitly probed in this study, this finding begets the question of whether the link between social impairment and heightened sensory sensitivity in autism (Hilton et al., 2010) may be related to aberrant connectivity between the brain stem and the amygdala.

The SF subregion of the amygdala is typically associated with olfactory processing; however, a growing body of evidence shows that it is also strongly involved with processing socially relevant and reward related information (Bzdok et al., 2013). Our exploratory hypotheses, based on the available information related to the SF, was that SF-limbic connectivity would be significantly different in ASD compared to TD and that it would be related to social dysfunction. Increased connectivity from the SF subregion showed the largest, most robust between-group differences, but not to limbic regions. Instead, the SF subregion showed increased connectivity to visual areas, a somatosensory region of the cerebellum, the paracingulate gyrus and the brainstem. While these findings were unexpected, and were not found in our correlational analyses of autism symptoms or of depression and anxiety symptoms, it is of note that a study of adolescent generalized anxiety disorder (Roy et al., 2013) found group differences in connectivity from the SF to almost identical regions of the brainstem and the paracingulate gyrus that were found in our analyses of between-group differences. However unlike our ASD group, individuals with generalized anxiety disorder showed decreased, not increased, connectivity to the brainstem (Roy et al., 2013). Increased connectivity between the right SF amygdala and the paracingulate gyrus was observed in both ASD and generalized anxiety disorder. The similarities across the two different populations suggest that further work focused on understanding the role of the SF subregion of the amygdala and psychiatric disorders may provide insight into shared developmental mechanisms.

Amygdala connectivity and symptoms of depression and anxiety in ASD

Because of the known links between the amygdala and mood and anxiety symptoms (Myers-Schulz & Koenigs, 2012), we conducted a series of analyses probing the relationship between amygdala connectivity and symptoms of depression and anxiety to explore similarities and differences in the neural circuitry affected in ASD. Correlations and interaction effects were tested for the BDI-II and BAI across TD and ASD adults. In general, co-morbid symptoms of anxiety and depression do not appear to be driving the between-group differences found in our study. Like with ASD symptoms, we found correlations between the LB subregion and depression, but in the opposite direction. Increased connectivity was correlated with increased levels of depression. Furthermore, there was little overlap between the brain regions involved in depression and social dysfunction. The two exceptions were the cerebellum and the fusiform gyrus. Level of depression was correlated with increased LB-cerebellar hemispheric connectivity, a relationship that has been reported previously in depression (albeit in the opposite direction) (Ramasubbu et al., 2014) while social dysfunction was related to reduced connectivity between the LB amygdala and vermal lobule IV, a region that has long been noted to be abnormal in autism (Courchesne, Yeung-Courchesne, Press, Hesselink, & Jernigan, 1988; Hashimoto et al., 1995; Kaufmann et al., 2003; Webb et al., 2009). There were no similarities between mood/anxiety and social dysfunction and connectivity from the CM and SF seed regions.

Our findings indicate that symptoms of depression and anxiety in individuals with ASD involve similar brain networks as individuals with primary mood and anxiety disorders; however, patterns of connectivity in ASD are differentially related to mood symptoms in individuals with primary mood and anxiety disorders or in TD individuals with subclinical symptom levels. We tested interaction effects in our sample and found that even with our very mildly symptomatic cohort, the relationship between mood/anxiety symptoms and connectivity was different in TD individuals and ASD individuals. Previous studies have identified CM subregion of the amygdala as a structure that plays a key role in the neural mechanisms involved in anxiety. In primates, the central nucleus was shown to be strongly predictive of anxious temperament (Oler et al., 2010) and, in rats, lesions to the CM subregion of the amygdala increase exploratory behavior, which may suggest reduced fear (Grijalva et al., 1990; Roy et al., 2013). In particular, studies in humans have found alterations in CM connectivity to the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a region that is involved in emotion regulation and fear extinction and has physiological connections to the CM amygdala. Our study of adults exhibiting minimal to moderate anxiety symptoms on the Beck Anxiety Inventory, found a significant interaction effect (p<.0001), such that in TD individuals, greater anxiety was associated with increased connectivity between the CM and the ACC, while in ASD, anxiety was associated with decreased CM-ACC connectivity (see Figure 3). Though this analysis is limited by a small sample and limited ranges of clinical symptoms, findings suggest that the neural mechanisms underlying the severity level of anxiety symptoms may be different in ASD.

We previously reported reduced connectivity between the amygdala and fusiform face area during an fMRI study of face processing, with higher levels of connectivity associated with milder social dysfunction (Kleinhans et al., 2008). Notably, the current analyses using resting-state data indicate that higher levels of intrinsic connectivity within of this neural circuit may also be associated with higher levels of depression in ASD (p<0.0001), while in TD participants; the lower levels of intrinsic connectivity are associated with higher levels of depression (p= 0.003; see Figure 3). These results provide the first neural evidence that higher levels of depression in ASD are associated with more intact limbic system circuitry, which may contribute to the relationship between level of functioning and depression in ASD (Vickerstaff, Heriot, Wong, Lopes, & Dossetor, 2007).

In conclusion, our findings provide new evidence of subregional differences in amygdala pathophysiology in ASD. These differences do not appear to be driven by co-morbid symptoms of depression and anxiety, suggesting distinct pathophysiological substrates underlying social dysfunction and mood symptoms. ASD diagnostic status and individual differences in symptom severity were associated with significantly decreased connectivity from the LB subregion and increased connectivity from the CM and SF subregions compared to typically developing controls. Co-morbid symptoms of depression and anxiety in the ASD participants were associated with both increased and decreased connectivity from the CM subregion and increased connectivity from the LB and SF subregions, in brain regions that were distinct from the correlations with core autism symptoms. In light of these results, it appears possible that anxiety and depression in ASD involve a true, biologically distinct co-morbidity with similar, but not identical, neural dysfunction as what is observed in individuals with primary anxiety and depression. Future studies should include individuals with a larger range of clinically significant symptoms, which will help determine whether or not these findings extend to individuals with more severe levels of clinical impairment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by:

Grant sponsor: NINDS/NIH; Grant number: 5K01NS059675

Grant sponsor: NICHD/NIH; Grant number: 5P50HD055782

Grant sponsor: Autism Speaks; Grant number: 3628

Footnotes

Authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Amunts K, Kedo O, Kindler M, Pieperhoff P, Mohlberg H, Shah NJ, Zilles K. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human amygdala, hippocampal region and entorhinal cortex: intersubject variability and probability maps. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2005;210(5–6):343–352. doi: 10.1007/s00429-005-0025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf M, Hyatt CJ, Wong CG, Johnson MR, Schultz RT, Hendler T, Pearlson GD. Mentalizing and motivation neural function during social interactions in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;3:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks SJ, Eddy KT, Angstadt M, Nathan PJ, Phan KL. Amygdala-frontal connectivity during emotion regulation. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2(4):303–312. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Diamond JB, Smith MA, Bandettini PA. Separating respiratory-variation-related fluctuations from neuronal-activity-related fluctuations in fMRI. Neuroimage. 2006;31(4):1536–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok D, Laird AR, Zilles K, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB. An investigation of the structural, connectional, and functional subspecialization in the human amygdala. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(12):3247–3266. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerliani L, Mennes M, Thomas RM, Di Martino A, Thioux M, Keysers C. Increased Functional Connectivity Between Subcortical and Cortical Resting-State Networks in Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, Yeung-Courchesne R, Press GA, Hesselink JR, Jernigan TL. Hypoplasia of cerebellar vermal lobules VI and VII in autism. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(21):1349–1354. doi: 10.1056/nejm198805263182102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20(3):775–803. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Webb SJ, McPartland J. Understanding the nature of face processing impairment in autism: insights from behavioral and electrophysiological studies. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;27(3):403–424. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2703_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmonte S, Gallagher L, O’Hanlon E, McGrath J, Balsters JH. Functional and structural connectivity of frontostriatal circuitry in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:430. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A, Yan CG, Li Q, Denio E, Castellanos FX, Alaerts K, Milham MP. The autism brain imaging data exchange: towards a large-scale evaluation of the intrinsic brain architecture in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(6):659–667. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets W, Price J, Furey M. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Structure and Function. 2008;213(1–2):93–118. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen A, Greenberg J, Seltzer M, Aman M. A Longitudinal Investigation of Psychotropic and Non-Psychotropic Medication Use Among Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(9):1339–1349. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0750-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffrey MS, Kleinhans NM, Haist F, Akshoomoff N, Campbell A, Courchesne E, Muller RA. Atypical [corrected] participation of visual cortex during word processing in autism: an fMRI study of semantic decision. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(8):1672–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Li TQ, Ress D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(1):162–167. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<162::aid-mrm23>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grijalva CV, Levin ED, Morgan M, Roland B, Martin FC. Contrasting effects of centromedial and basolateral amygdaloid lesions on stress-related responses in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1990;48(4):495–500. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90289-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Tayama M, Murakawa K, Yoshimoto T, Miyazaki M, Harada M, Kuroda Y. Development of the brainstem and cerebellum in autistic patients. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF02178163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton CL, Harper JD, Kueker RH, Lang AR, Abbacchi AM, Todorov A, LaVesser PD. Sensory responsiveness as a predictor of social severity in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(8):937–945. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0944-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana RK, Liu Y, Williams DL, Keller TA, Schipul SE, Minshew NJ, Just MA. The local, global, and neural aspects of visuospatial processing in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51(14):2995–3003. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Cooper KL, Mostofsky SH, Capone GT, Kates WR, Newschaffer CJ, Lanham DC. Specificity of cerebellar vermian abnormalities in autism: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. J Child Neurol. 2003;18(7):463–470. doi: 10.1177/08830738030180070501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keehn B, Brenner L, Palmer E, Lincoln AJ, Muller RA. Functional brain organization for visual search in ASD. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14(6):990–1003. doi: 10.1017/s1355617708081356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Szatmari P, Bryson SE, Streiner DL, Wilson FJ. The Prevalence of Anxiety and Mood Problems among Children with Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Autism. 2000;4(2):117–132. doi: 10.1177/1362361300004002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, Lyoo IK, Estes AM, Renshaw PF, Shaw DW, Friedman SD, Dager SR. Laterobasal amygdalar enlargement in 6- to 7-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1187–1197. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans NM, Johnson LC, Richards T, Mahurin R, Greenson J, Dawson G, Aylward E. Reduced neural habituation in the amygdala and social impairments in autism spectrum disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):467–475. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans NM, Richards T, Johnson LC, Weaver KE, Greenson J, Dawson G, Aylward E. fMRI evidence of neural abnormalities in the subcortical face processing system in ASD. Neuroimage. 2011;54(1):697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans NM, Richards T, Sterling L, Stegbauer KC, Mahurin R, Johnson LC, Aylward E. Abnormal functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders during face processing. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 4):1000–1012. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans NM, Richards T, Weaver K, Johnson LC, Greenson J, Dawson G, Aylward E. Association between amygdala response to emotional faces and social anxiety in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(12):3665–3670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux L, Salek-Haddadi A, Lund TE, Laufs H, Carmichael D. Modelling large motion events in fMRI studies of patients with epilepsy. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(6):894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AC, Doshi J, Polsky DE. Psychotropic Medication Use Among Medicaid-Enrolled Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e441–e448. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Borue X, Day TN, Minshew NJ. Emotion regulation patterns in adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: comparison to typically developing adolescents and association with psychiatric symptoms. Autism Res. 2014;7(3):344–354. doi: 10.1002/aur.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Folstein SE, Lainhart JE. Overrepresentation of mood and anxiety disorders in adults with autism and their first-degree relatives: what does it mean? Autism Res. 2008;1(3):193–197. doi: 10.1002/aur.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Topographical organization of amygdaloid projections to the caudatoputamen, nucleus accumbens, and related striatal-like areas of the rat brain. Neuroscience. 1991;44(1):15–33. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90248-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CP, Zimmerman PE, Gothard KM. Response characteristics of basolateral and centromedial neurons in the primate amygdala. J Neurosci. 2010;30(48):16197–16207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3225-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RA. The study of autism as a distributed disorder. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(1):85–95. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RA, Shih P, Keehn B, Deyoe JR, Leyden KM, Shukla DK. Underconnected, but How? A Survey of Functional Connectivity MRI Studies in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21(10):2233–2243. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers-Schulz B, Koenigs M. Functional anatomy of ventromedial prefrontal cortex: implications for mood and anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(2):132–141. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oler JA, Fox AS, Shelton SE, Rogers J, Dyer TD, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH. Amygdalar and hippocampal substrates of anxious temperament differ in their heritability. Nature. 2010;466(7308):864–868. doi: 10.1038/nature09282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasubbu R, Konduru N, Cortese F, Bray S, Gaxiola-Valdez I, Goodyear B. Reduced intrinsic connectivity of amygdala in adults with major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richey JA, Damiano CR, Sabatino A, Rittenberg A, Petty C, Bizzell J, Dichter GS. Neural Mechanisms of Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2359-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Fudge JL, Kelly C, Perry JS, Daniele T, Carlisi C, Ernst M. Intrinsic functional connectivity of amygdala-based networks in adolescent generalized anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(3):290–299.e292. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow MJ, Mahajan G, May W, Overholser JC, Jurjus GJ, Dieter L, Stockmeier CA. Basolateral amygdala volume and cell numbers in major depressive disorder: a postmortem stereological study. Brain Struct Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0900-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(3):803–834. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahyoun CP, Belliveau JW, Soulieres I, Schwartz S, Mody M. Neuroimaging of the functional and structural networks underlying visuospatial vs. linguistic reasoning in high-functioning autism. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(1):86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Rubia K, van Amelsvoort T, Daly E, Smith A, Murphy DG. Neural correlates of reward in autism. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(1):19–24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann CM, Amaral DG. Stereological analysis of amygdala neuron number in autism. J Neurosci. 2006;26(29):7674–7679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1285-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Dapretto M, Ghahremani DG, Poldrack RA, Bookheimer SY. Reward processing in autism. Autism Res. 2010;3(2):53–67. doi: 10.1002/aur.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli K, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Horovitz SG, Fukunaga M, Jansma JM, Duyn JH. Low-frequency fluctuations in the cardiac rate as a source of variance in the resting-state fMRI BOLD signal. Neuroimage. 2007;38(2):306–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Beaulieu A. Psychotropic Medications in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Synthesis for Evidence-Based Practice. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(8):1592–1605. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling L, Dawson G, Estes A, Greenson J. Characteristics associated with presence of depressive symptoms in adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(6):1011–1018. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0477-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman A, Duncan JS, Yang DY, Pelphrey KA. An unbiased Bayesian approach to functional connectomics implicates social-communication networks in autism. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;8:356–366. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerstaff S, Heriot S, Wong M, Lopes A, Dossetor D. Intellectual ability, self-perceived social competence, and depressive symptomatology in children with high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(9):1647–1664. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SJ, Sparks BF, Friedman SD, Shaw DW, Giedd J, Dawson G, Dager SR. Cerebellar vermal volumes and behavioral correlates in children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;172(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.