Abstract

Study Objectives:

To investigate the potentially bidirectional association between gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) and sleep disturbances/ insomnia disorders.

Methods:

We assessed the incidence of new-onset of self-reported GERS, sleep disturbances, and insomnia disorders in a population-based longitudinal cohort study (HUNT), performed in Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway. Modified Poisson regression was used to estimate risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, tobacco smoking, educational level, anxiety, and depression.

Results:

The study cohort included the 25,844 participants of the HUNT study who responded to health questionnaires in both 1995–1997 and 2006–2009. New-onset GERS, sleep disturbances, and insomnia disorders was reported in 396 (2%), 2,598 (16%), and 497 (3%) participants, respectively. Persistent sleep disturbances were associated with new-onset GERS (RR: 2.70, 95% CI: 1.93–3.76), persistent insomnia disorders were associated with new-onset GERS (RR: 3.42; 95% CI: 1.83–6.39) and persistent GERS was associated with new-onset sleep disturbances (RR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.14–1.75).

Conclusions:

Sleep disturbances and GERS seem to be bidirectionally associated, and sleep disturbances seem to be a stronger risk factor for GERS than the reverse.

Citation:

Lindam A, Ness-Jensen E, Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Åkerstedt T, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Gastroesophageal reflux and sleep disturbances: a bidirectional association in a population-based cohort study, the HUNT study. SLEEP 2016;39(7):1421–1427.

Keywords: gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, insomnia, sleep disturbances, epidemiology, HUNT

Significance.

The present study found that sleep disturbances and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) are bidirectionally associated, suggesting that sleep disturbances may lead to GERS and vice versa. The study indicates a stronger association between sleep disturbances and risk of GERS than the opposite. The results are supported by the longitudinal design that enabled assessment of new-onset sleep disturbances and GERS and an observed dose-response relation, with increased risk with longer exposure. The study highlights the need for research aiming at preventing or treating both of these disorders. Interventional studies addressing whether treatment of sleep disturbances decreases the risk of developing GERS and whether effective treatment of GERS counteracts sleep disturbances are warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Both gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) and sleep disturbances are major public health concerns. Troublesome and weekly GERS affect up to 30% of adults in Western populations, and are associated with adverse health-related quality of life, increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, and large costs for patients and society.1–6 Established risk factors for GERS are overweight, heredity, and tobacco smoking.3,7,8 Sleep disturbances affect up to one-third of the adult population, negatively influence health in general, and increase the risk of unintentional fatal injuries and traffic accidents.9–12 An association between sleep disturbances and GERS has been indicated,13,14 and it has been suggested that the association is bidirectional and stronger regarding GERS in relation to new-onset sleep disturbances/insomnia disorders than the opposite.15,16 However, to our knowledge, no population-based study including data on the incidence of these disorders has been conducted. Therefore, the present study addressed the direction of the association between GERS and sleep disturbances/insomnia disorders in a large, prospective, and longitudinal cohort study using data from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT).

METHODS

Design and Participants

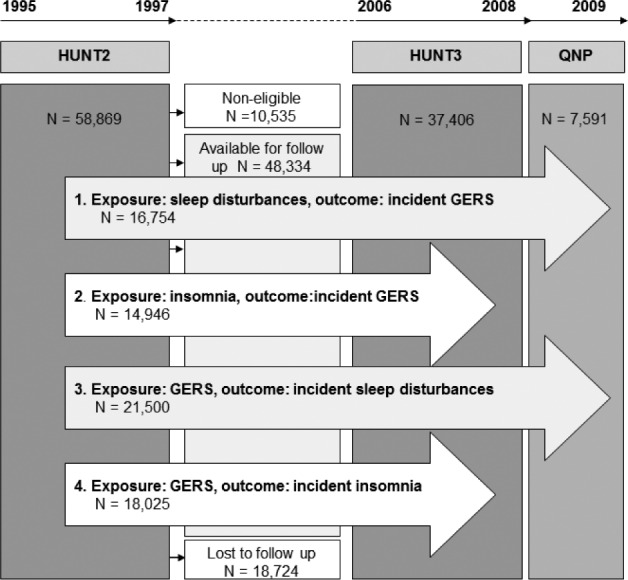

Data were assessed based on two HUNT surveys, i.e., HUNT2 conducted in 1995–1997 and HUNT3 conducted in 2006–2008, to design a longitudinal prospective cohort study with an average duration of 11 years between data collections in the 2 surveys. These population-based surveys contained questionnaires addressing health and diseases, including GERS and sleep disturbances, administered to all adults living in the entire county of Nord-Trøndelag in Norway. In HUNT2, all 93,898 residents of at least 19 years of age were invited to participate, and 58,869 (64% of the eligible) did.2 Participants older than age 67 (retirement age in Norway) were excluded since one of the sleep disturbance items in HUNT2 used for defining insomnia symptoms addressed impaired work performance due to sleep problems. In HUNT3, 37,406 out of 91,530 eligible (41%) individuals participated in a health survey similar to HUNT2. Due to the lower participation rate in HUNT3 compared to HUNT2, 45,500 non-participants were in 2009 invited to answer a short version of the health questionnaire (Questionnaire of Non-Participants [QNP]),17 including GERS and sleep disturbance items. In total 7,591 (17%) individuals participated in QNP, resulting in a total number of 44,997 (49%) participants in both HUNT3/QNP.2 All participants who responded to the items addressing GERS status and sleep disturbances in both surveys (HUNT2 and HUNT3/QNP) were included in the present study (n = 25,844). The main outcomes/exposure variables were severe GERS and 2 types of sleep problems; sleep disturbances and insomnia disorders. These 3 variables are defined below. The items used to assess insomnia disorders were not included in QNP, and therefore the analyses of insomnia disorders, either as outcome or exposure, were restricted to HUNT2 and HUNT3. Thus, 4 different cohorts were used including all combinations of outcomes and exposures (Figure 1):

Cohort 1 assessed the cumulative incidence of GERS in HUNT3/QNP among participants without GERS in HUNT2, and the exposure was prevalent sleep disturbances.

Cohort 2 assessed the cumulative incidence of GERS in HUNT3 among participants without GERS in HUNT2, and the exposure was prevalent insomnia disorders.

Cohort 3 assessed the cumulative incidence of sleep disturbances in HUNT3/QNP among participants without sleep disturbances in HUNT2, and the exposure was prevalent GERS.

Cohort 4 assessed the cumulative incidence of insomnia disorders in HUNT3 among participants without insomnia disorders in HUNT2, and the exposure was prevalent GERS.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the participants in HUNT2, HUNT3, and QNP and the four study cohorts. Cohort 1 assessed the cumulative incidence of severe gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) in HUNT3/QNP among participants without GERS in HUNT2 with sleep problems as exposure. Cohort 2 assessed the cumulative incidence of severe GERS in HUNT3 among participants without GERS in HUNT2 with insomnia symptoms as exposure. Cohort 3 assessed the cumulative incidence of sleep disturbances in HUNT3/QNP among participants without sleep disturbances in HUNT2 with severe GERS as exposure. Cohort 4 assessed the cumulative incidence of insomnia disorder in HUNT3 among participants without insomnia disorder in HUNT2 with severe GERS as exposure.

Assessment of GERS

GERS were assessed with the same questions in HUNT2 and HUNT3/QNP: “To what degree have you had heartburn and/or acid regurgitation during the previous 12 months?” and the response alternatives were: “no complaints,” “minor complaints,” or “severe complaints.” If an individual answered “severe complaints,” he or she was defined as having GERS. We have previously validated the GERS question used in HUNT in a separate study,18 comparing the HUNT GERS questions with a more extensive and well-established GERS questionnaire. This validation study showed that among individuals reporting severe complaints 72% experienced daily and 95% at least weekly symptoms.18 This corresponds well to the current definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease based on symptom assessment.19

Assessment of Sleep Disturbances and Insomnia Disorders

Sleep problems were defined as 2 separate outcomes/exposures: the more general sleep disturbances and the stricter insomnia disorders. Sleep disturbances were assessed with the questions “Have you had difficulty falling asleep during the last month?” and “During the last month, have you woken too early and not been able to get back to sleep?” in HUNT2, with response alternatives “almost every night,” “often,” “now and again,” or “never.” If participants answered “almost every night” or “often” on one of these items they were classified as having sleep disturbances. In HUNT3/QNP sleep problems were assessed with similar questions: “How often during the last 3 months have you had difficulty falling asleep at night?” and “How often during the last 3 months have you woken too early and couldn't get back to sleep,” with response alternatives “never/seldom,” “sometimes,” or “several times a week.” Participants who answered “several times a week” on either item (or both) were classified as having sleep disturbances. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria for primary insomnia include having difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or experiencing non-restorative sleep for at least one month.20 In addition, it is a prerequisite that the sleep disturbances have a clinically significant adverse impact on social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.20 We constructed an insomnia proxy based on the following questions in HUNT2: “Have you had difficulty falling asleep during the last month?” “During the last month, have you woken too early and not been able to go get back to sleep?” and “During the last year, have you been troubled by insomnia to such a degree that it affected your work?” A participant was defined as suffering from insomnia disorders if responding “almost every night” or “often” to initiating or maintaining sleep in combination with experiencing impaired work performance due to insomnia during the last year. In HUNT3 insomnia was assessed by the questions: “How often during the last 3 months have you had difficulty falling asleep at night?” “How often during the last 3 months have you woken up too early and couldn't go back to sleep?” and “How often during the last 3 months have you felt sleepy during the day?” If a participant answered “several times a week” on initiating or maintaining sleep and “feeling sleepy during the day,” that participant was considered to suffer from insomnia disorders. Since there was no question assessing any influence of sleep disturbance on daily life in QNP, the assessment of insomnia symptoms was restricted to HUNT2 and HUNT3. This definition of insomnia has been used in prior studies investigating the bidirectional associations between depression and insomnia, and insomnia and work performance.21,22

Assessment of Potential Confounders

The potential confounders considered in the study were sex, age, body mass index (BMI), tobacco smoking, educational level anxiety, and depression. These variables were assessed through questionnaires in HUNT3/QNP, except for education, anxiety, and depression, which were assessed in HUNT2. Depression and anxiety were measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),23 which consists of 7 questions assessing symptoms of anxiety during the last week and 7 regarding depression. Each item could be answered with a score 0–3, with 0 = no symptom present. The scales were summarized separately and a score ≥ 8 indicated presence of anxiety and depression, respectively. BMI was based on weight and height objectively measured during standardized conditions by trained personnel at screening stations in HUNT3, and self-reported in QNP.

Statistical Analyses

Modified Poisson regression was used to estimate risk ratios (RRs),24 and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), of the 3 outcomes, i.e., GERS, sleep disturbances, and insomnia disorders. The 4 sub-cohorts were analyzed separately (Figure 1). The multivariable models provided RRs adjusted for the potential confounders described above, categorized as follows: sex (women or men), age (< 40, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, or ≥ 70 years), BMI (< 25, 25–30, or ≥ 30), tobacco smoking status (current smoker, previous smoker, or never smoker), educational level (≤ 12 years or > 12 years), and anxiety and depression (none, anxiety, depression, both anxiety and depression). All exposures were coded in the same way: (1) no exposure, (2) exposure in the first assessment (HUNT2), but not in the second (HUNT3/ QNP), (3) exposure in the second assessment (HUNT3/QNP), but not in the first (HUNT2), and (4) exposure in both assessments (HUNT2 and QNP). SAS software 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Central Norway (number: 2013/390) and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (number: 2010/582-31/1). Written and oral informed consent was obtained from all participants in conjunction with the data collections.

RESULTS

Prevalence and Characteristics

The prevalence of sleep disturbances was 11% (n = 2,642) among the study population in HUNT2 and 18% (n = 4,289) in HUNT3/QNP, while the prevalence of insomnia disorders was 5% (n = 1,036) in HUNT2 and 5% (n = 1,006) in HUNT3. The prevalence of GERS was 5% (n = 1,203) in HUNT2 and 7% (n = 1,642) in HUNT3.

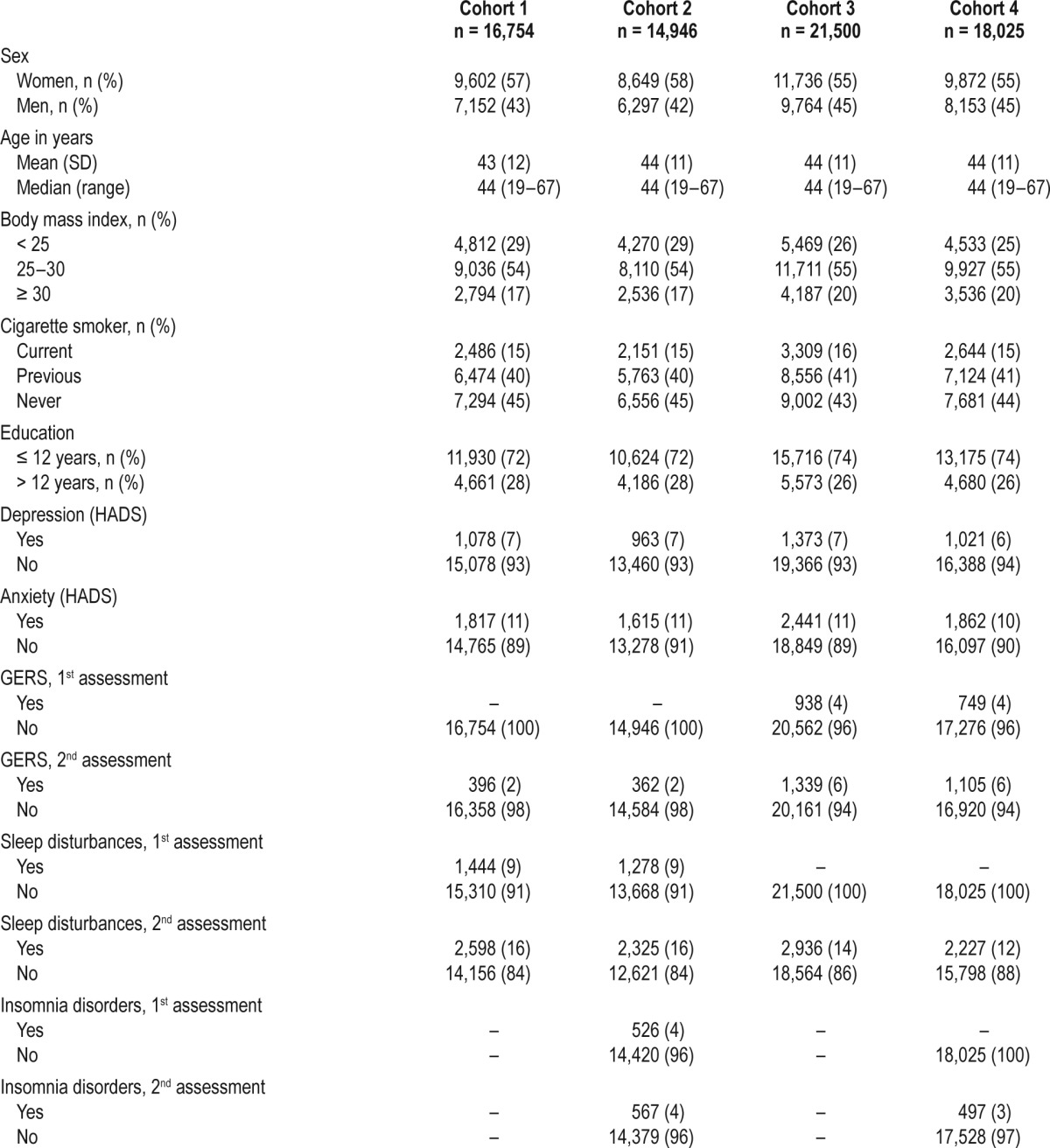

Characteristics of the participants in the 4 sub-cohorts are presented in Table 1. The cohorts were very similar in terms of age distribution, tobacco smoking, educational level, depression, and anxiety. The mean age range (measured in HUNT2) was 43–44 years, 15% to 16% were current smokers, and 26% to 28% had an educational level > 12 years. Depression was present in 6% to 7% of the participants, and 10% to 11% reported anxiety according to the HADS-scale. More women than men participated, particularly in cohort 1 and 2. The prevalence of obesity and overweight were slightly higher (20% compared to 17%) among participants in cohort 3 and 4 compared to cohort 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics over the study population in the four different cohorts.

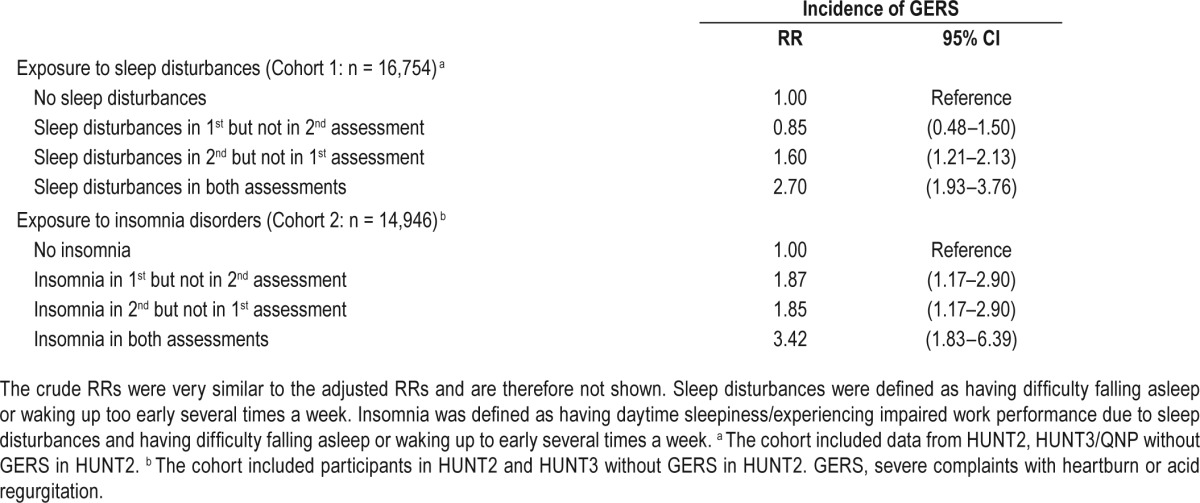

Sleep Disturbances and Insomnia Disorders as Risk Factors for Developing GERS

In total, 396 (2%) participants developed GERS between the first and second assessment (Table 1). Among participants with sleep disturbances in both assessments, the risk of new onset of GERS was 2.7 times higher than among those with no sleep disturbances (adjusted RR 2.70, 95% CI 1.93–3.76) and 60% higher among those with sleep disturbances at assessment 2 only (adjusted RR 1.60, 95% CI 1.21–2.13; Table 2). When the exposure was restricted to insomnia disorders, the risk of new onset of GERS was 3.4 times higher (adjusted RR 3.42, 95% CI 1.93–3.76) compared to those without insomnia disorders. Participants only exposed at first assessment or only exposed at the second assessment also had an increased risk of GERS than the none-exposed (RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.17–2.90 and RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.17–2.90 respectively). Since the crude RRs were similar to the adjusted RRs, only the adjusted RRs are shown (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exposure to sleep disturbances and insomnia disorders and relative risk of severe gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS). Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were adjusted for sex, age, body mass index (BMI), tobacco smoking, education, anxiety, and depression.

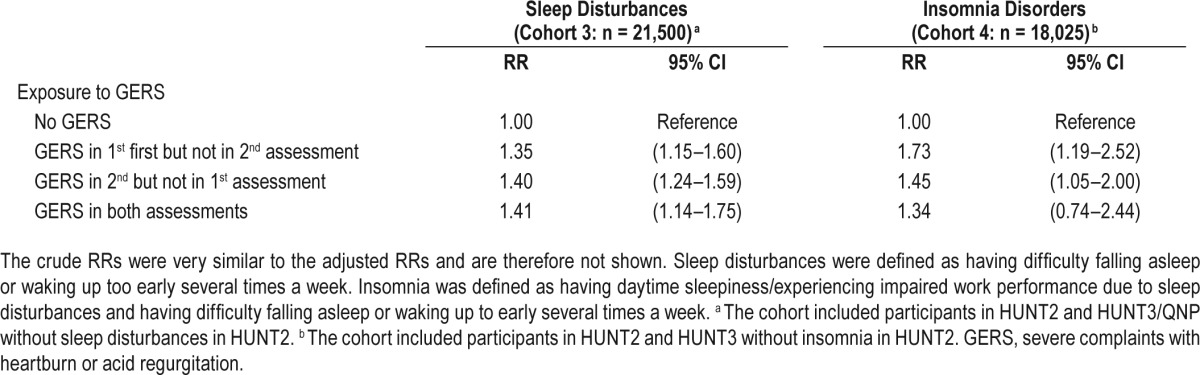

GERS as Risk Factors for Developing Sleep Disturbances and Insomnia Disorders

Between the 2 assessments, 2,936 participants (8%) developed sleep disturbances and 497 participants (3%) developed insomnia disorders (Table 1). Compared to those not reporting GERS, participants with GERS at both assessments had a 41% increased risk of sleep disturbances (adjusted RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.14–1.75; Table 3). Those who only experienced GERS at the first assessment had a 35% increased risk (adjusted RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.15–1.60), and those who only had GERS at the second assessment had a 40% increased risk (adjusted RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.24–1.59). The risk of insomnia disorders was 73% higher among those who were exposed to GERS at the first assessment (adjusted RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.19–2.52) and 45% higher among those who were exposed at the second assessment (adjusted RR 1.45, 95% CI 1.05–2.00), compared to non-exposed to GERS. There was no statistically significant increased risk for insomnia disorders among those exposed to GERS at both assessments (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.74–2.44). Since the crude RRs were similar to the adjusted RRs, only the adjusted RRs are shown (Table 3).

Table 3.

Exposure to severe gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) and risk of sleep disturbances and insomnia disorder. Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, smoking, education, anxiety, and depression.

DISCUSSION

This study indicates a strongly increased risk of developing GERS among individuals with sleep disturbances and insomnia disorders, and a moderately increased risk of developing sleep disturbances among persons with GERS. Those having a longer time (exposure present at both surveys) with sleep disturbances and insomnia disorders had a more strongly increased risk of developing GERS than those participants who reporting sleep disturbances in the first survey only.

Previous studies investigating the association between GERS and sleep disturbances have indicated that sleep disorders and GERS might aggravate the other, resulting in a vicious circle.15,16 In our previous study using HUNT data (HUNT1 and HUNT2), including 65,333 participants, an association between insomnia symptoms and GERS was found, but due to the cross-sectional design the direction of the association was impossible to estimate, as data on outcomes and exposures were only collected once (in HUNT2).13 A primary care intervention study including 1,388 patients showed that patients having sleep disorders when given a screening test for GERS and treated whenever GERS was found, experienced improvement of their sleep problems.25 A US population-based study of 11,685 participants with GERS showed that as many as 49.1% had difficulty initiating sleep and 58.3% had difficulty maintaining sleep.26 These studies, together with the present investigation, support an association between GERS and sleep disturbances. The dose-response patterns observed in the present study further strengthen these findings.

The main novel finding of the present study is the ability to estimate the bidirectional association between GERS and sleep disturbances. Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly, the present study indicates a stronger association between sleep disturbances or insomnia disorders as a risk factor for GERS than the opposite. However, several potentially relevant physiological differences between being asleep and being awake are well documented, including delayed gastric emptying, decreased transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation, decreased basal esophageal sphincter pressure, and decreased primary and secondary esophageal peristalsis during sleep.16 All these physiological changes increase the risk of reflux events at night.16 Moreover, sleep deprivation may lead to enhanced esophageal sensitivity to acidic exposure, which was found in a randomized controlled trial,27 and therefore individuals with insomnia might be more prone to experience GERS than individuals without insomnia. On the other hand, nocturnal reflux is known to cause arousals, both conscious and unconscious,28 and arousals from sleep lead to impaired sleep quality.29

Strengths of the present study include the longitudinal design (enabling assessment of cumulative incidence of GERS, sleep disturbances and insomnia disorders), the prospective data collection, the large sample size, and the ability to adjust the results for several potential confounders, particularly anxiety and depression. Some limitations include the different time windows of assessment of sleep disturbances in the first assessment (last month) and the second assessment (last three months), which might have introduced information bias. However, any such misclassification should be non-differential between exposure groups and therefore only dilute the risk estimates, and thus not explain the associations. Moreover, data were collected at two time periods and thus only cumulative incidence (incidence proportion) could be estimated, i.e., estimation of person-years and, thus, incidence rate ratios were not possible. Therefore, participants experiencing GERS or sleep disturbances between the two data collections might have been excluded or erroneously estimated as not having the outcome or exposure under study. Furthermore, the lack of information on diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in the study population might be a limitation since an association between OSA, sleep disturbances, and GERS has been suggested.30 However, while the evidence for OSA and sleep disturbances is strong, the evidence regarding OSA and GERS is conflicting with several studies showing no association.31,32 Another limitation might be the self-assessed nature of GERS and sleep disturbances. The use of questionnaires to define GERS is, however, considered the diagnostic method of choice,33 and is consistent with the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease.19 The sleep problems and insomnia items in HUNT have also successfully been used in previous studies,13,22 and the insomnia symptoms definition used meets to a high degree criteria stipulated for primary insomnia in DSM-IV.20

The findings of this study highlight the need for research aiming at preventing or treating both sleep disturbances and GERS. Interventional studies addressing whether treatment of sleep disturbances decreases the risk of developing GERS, and whether effective treatment of GERS counteracts sleep disturbances are warranted.

In conclusion, in this first large and longitudinal cohort study assessing the relation between incident GERS and sleep disturbances a bidirectional association has been observed. The association between sleep disturbances or insomnia disorders and incident GERS might be stronger than the association between GERS and incident sleep disturbances or insomnia disorders.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Funding was provided by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the Swedish Research Council (SIMSAM). The HUNT study is performed through collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Department of Public Health and General Practice, Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871–80. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ness-Jensen E, Lindam A, Lagergren J, Hveem K. Changes in prevalence, incidence and spontaneous loss of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a prospective population-based cohort study, the HUNT study. Gut. 2012;61:1390–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms and the influence of age and sex. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1040–5. doi: 10.1080/00365520410003498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiklund I. Review of the quality of life and burden of illness in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2004;22:108–14. doi: 10.1159/000080308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansson C, Wiberg M, Alexanderson K. Sickness absence due to gastroesophageal reflux diagnoses: a nationwide Swedish population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:17–26. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.737359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Z, Nordenstedt H, Pedersen NL, Lagergren J, Ye W. Lifestyle factors and risk for symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux in monozygotic twins. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:87–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivertsen B, Lallukka T, Salo P, et al. Insomnia as a risk factor for ill health: results from the large population-based prospective HUNT Study in Norway. J Sleep Res. 2014;23:124–32. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansson C, Alexanderson K, Kecklund G, Akerstedt T. Clinically diagnosed insomnia and risk of all-cause and diagnosis-specific sickness absence: a nationwide Swedish prospective cohort study. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41:712–21. doi: 10.1177/1403494813498003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laugsand LE, Strand LB, Vatten LJ, Janszky I, Bjorngaard JH. Insomnia symptoms and risk for unintentional fatal injuries--the HUNT Study. Sleep. 2014;37:1777–86. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander MA, et al. A population-based study showing an association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep problems. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:960–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindam A, Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Pedersen NL, Lagergren J. A population-based study of gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep problems in elderly twins. PloS One. 2012;7:e48602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung HK, Choung RS, Talley NJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep disorders: evidence for a causal link and therapeutic implications. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:22–9. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T, Fass R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and sleep. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langhammer A, Krokstad S, Romundstad P, Heggland J, Holmen J. The HUNT study: participation is associated with survival and depends on socioeconomic status, diseases and symptoms. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Obesity and estrogen as risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. JAMA. 2003;290:66–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. quiz 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sivertsen B, Overland S, Neckelmann D, et al. The long-term effect of insomnia on work disability: the HUNT-2 historical cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1018–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sivertsen B, Salo P, Mykletun A, et al. The bidirectional association between depression and insomnia: the HUNT study. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:758–65. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182648619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scan. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moayyedi P, Hunt R, Armstrong D, Lei Y, Bukoski M, White R. The impact of intensifying acid suppression on sleep disturbance related to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:730–7. doi: 10.1111/apt.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mody R, Bolge SC, Kannan H, Fass R. Effects of gastroesophageal reflux disease on sleep and outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:953–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schey R, Dickman R, Parthasarathy S, et al. Sleep deprivation is hyperalgesic in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1787–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poh CH, Allen L, Gasiorowska A, et al. Conscious awakenings are commonly associated with Acid reflux events in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:851–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orr WC, Goodrich S, Robert J. The effect of acid suppression on sleep patterns and sleep-related gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:103–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green BT, Broughton WA, O'Connor JB. Marked improvement in nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux in a large cohort of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:41–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim HN, Vorona RD, Winn MP, Doviak M, Johnson DA, Ware JC. Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and the severity of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome are not related in sleep disorders center patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1127–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuribayashi S, Massey BT, Hafeezullah M, et al. Upper esophageal sphincter and gastroesophageal junction pressure changes act to prevent gastroesophageal and esophagopharyngeal reflux during apneic episodes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2010;137:769–76. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, et al. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:52–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]