Abstract

The incidence of occupational injuries and diseases associated with industrialization has declined markedly following developments in science and technology, such as engineering controls, protective equipment, safer machinery and processes, and greater adherence to regulations and labor inspections. Although the introduction of health and safety management systems has further decreased the incidence of occupational injuries and diseases, these systems are not effective unless accompanied by a positive safety culture in the workplace. The characteristics of work in the 21st century have given rise to new issues related to workers' health, such as new types of work-related disorders, noncommunicable diseases, and inequality in the availability of occupational health services. Overcoming these new and emerging issues requires a culture of prevention at the national level. The present paper addresses: (1) how to change safety cultures in both theory and practice at the level of the workplace; and (2) the role of prevention culture at the national level.

Keywords: change, health promotion, occupational health, prevention culture, safety culture

1. Management and culture

The incidence of occupational injuries and diseases associated with industrialization has declined markedly following developments in science and technology, such as engineering controls, protective equipment, safer machinery and processes, and adherence to regulations and labor inspections [1]. However, the decline in occupational injuries and diseases has only been minimal, leading to increased interest in health and safety management systems. Although the introduction of these systems has further reduced the incidence of occupational injuries and diseases, occupational safety and health management systems are not effective in workplaces with a poor safety culture [1]. The International Labour Organization (ILO) also noted that a key element for occupational safety and health management is promoting a culture of prevention within the enterprise [2]. Introduction of a positive safety culture can therefore achieve further reductions in occupational injuries and diseases.

The first time the term “safety culture” appeared in the literature was when the International Atomic Energy Agency introduced the term in its 1986 Chernobyl Accident Summary Report to describe how the thinking and behaviors of people in the organization responsible for safety in that nuclear plant contributed to the accident [3].

In 1993, the Advisory Committee on Safety of Nuclear Installation (ACSNI) investigated disasters such as the Chernobyl meltdown, the Kings Cross fire, the Piper Alpha explosion, and the train crash at Clapham Junction, concluding that safety systems in these workplaces had broken down. These breakdowns were not caused by the method of managing safety, but by problems with the “safety culture” of the responsible organizations. The lesson drawn from these disasters was that “it is essential to create a corporate atmosphere or culture in which safety is understood to be and is accepted as the number one priority” [4].

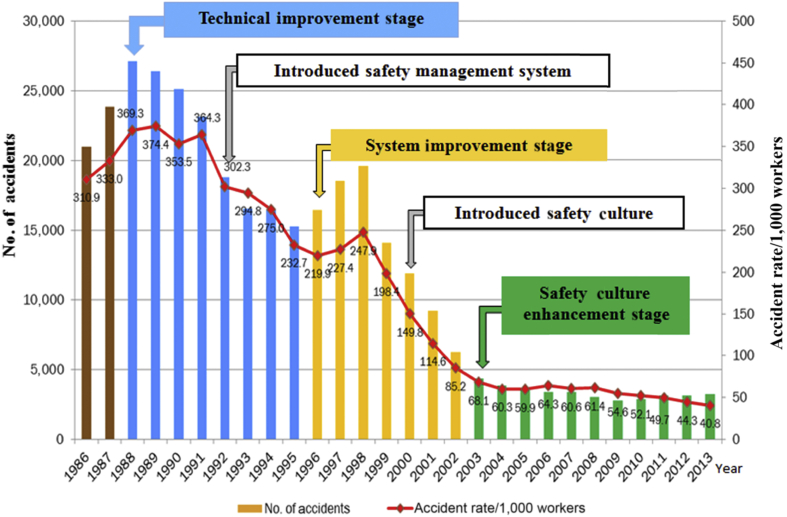

Fig. 1 displays accident statistics over time in the construction industry in Hong Kong from 1986 to 2013, showing that the development of a safety culture markedly reduced the number of accidents [5]. Although technology and occupational health and safety management systems have made great strides in creating a safer world, the introduction and enhancement of a safety culture within the workplace is the key to further improvements. The Hong Kong Occupational Safety & Health Council promoted work safety awareness in employers and employees of high-risk trades to promote safety culture in workplaces. This organization also cultivated safety culture at the community level and developed a “safety culture index” to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies that attempt to improve safety culture [5].

Fig. 1.

Accident statistics of the construction industry in Hong Kong.

An occupational safety and health management system is not effective unless it is accompanied by a positive safety culture in the workplace [1]. Many organizations that have introduced new occupational health and safety management strategies have failed to show improved effectiveness because these strategies did not consider the impact of the organizational culture.

Work in the 21st century has been characterized by expansions in the service and knowledge sectors, increases in the numbers of small businesses, nontraditional work schedules, precarious workers, worker mobility, and older-aged workers [6], [7]. These characteristics have resulted in new and emerging issues related to workers' health, including new types of work-related disorders, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), and inequality in the availability of occupational health services [8], [9]. Overcoming these new and emerging issues requires a culture of prevention at the national level.

The objective of the present paper is to address: (1) how to change safety cultures in both theory and practice at the level of the workplace; and (2) the role of prevention culture at the national level to deal with new and emerging work-related health issues as well as traditional occupational diseases in the rapidly changing work environment.

2. Definition of safety culture

In 1993, the ACSNI Human Factors Study Group defined safety culture as “the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies and patterns of behavior that can determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of an organization's health and safety management system” [4]. A safety culture has psychological, behavioral, and situational components. The psychological component consists of shared values, attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs that drive decisions and behaviors regarding safety [10]. The behavioral component can be defined as the methods regarding safety in the workplace, and the situational component as the policies, procedures, regulations, organizational structures, and management systems related to safety.

The International Atomic Energy Agency has described five characteristics of a positive safety culture [11]. First, leadership is the highly visible commitment to safety by top management, a characteristic vital for providing a positive safety culture. Second, safety should be clearly communicated as a value, not as a priority that can be traded off against cost and schedule. Third, decentralized decision-making and accountability of key groups responsible for safety is important for creating and maintaining a positive safety culture. Fourth, all employees should learn about safety and contribute ideas on improved safety. A positive safety culture is achieved when employees learn from insight and intuition rather than incidents, and change their ways of thinking and acting by sharing their experiences and addressing shared problems. Finally, a positive safety culture is one in which safety is a top priority and is integrated into every aspect of the company. In particular, among the five characteristics, the leadership of employers is the key to developing a positive safety culture.

Single organizations have unique organizational cultures and safety cultures. Safety culture can be divided into five levels of development, from “Pathological,” to “Reactive,” to “Calculative,” to “Proactive,” to “Generative” [12], [13], [14]. In a “Pathological” safety culture, employers and workers do not care about violating safety rules; this is often termed a “No care” safety culture. In a “Reactive” safety culture, safety becomes important only after an accident; this is often called a “Blame safety culture.” In a “Calculative” safety culture, systems are in place to manage all hazards; this is often called a “Planned safety culture.” In a “Proactive” safety culture, workers do not work on problems they find, but avoid problems in advance to improve the work environment. A “Generative” safety culture is a dynamic safety culture, in which safety is built into ways of working and thinking. Thus, a poor or pathological safety culture can develop into a positive or generative safety culture when a change in culture is properly managed.

3. A theory of culture change

The Cultural Web, developed by Jerry Johnson in 1992, provides an approach for changing an organization's culture. It identifies six interrelated elements that make up the “paradigm,” a term brought into common currency by Thomas Kuhn in his 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions [15]. According to the Cultural Web model [15], the paradigm is the set of core beliefs that maintain the unity of the culture. Stories, rituals and routines, symbols, control system, and power and/or organizational structures are the manifestations of culture that result from the paradigm. Most programs that seek to promote organizational change concentrate only on the superficial or visible aspects of a culture. Unless the central paradigm changes, long-lasting organizational change will not occur. The late Chinese political leader Mao Tse-Tung said, “People's attitudes and opinions have been formed over decades of life and cannot be changed by holding a few meetings or giving a few lectures” [16].

Many models of change have their roots in the work of Kurt Lewin. His book, Field Theory in Social Science, describes a three-step model of change that is often called the unfreeze–change–refreeze model [17]. This culture change theory was further developed by Professor Edgar Schein, a distinguished management consultant and organizational psychologist who developed the main model for understanding an organizational culture and also provided details on culture change [18], [19], [20]. According to the three-step model of change, change requires an old system to go through three steps of unfreezing–changing–refreezing stages in order to reach an improved new system that then becomes stabilized [20]. For change to occur, the present equilibrium needs to be destabilized (or unfrozen), so that old behavior can be discarded (unlearned) and new behavior can be adopted. Unfreezing is the most difficult and important stage in creating a motivation to change. The unfreezing process consists of three subprocesses—disconfirmation, survival anxiety, and creation of psychological safety—which are related to the readiness and motivation to change [20]. Disconfirmation refers to present conditions that lead to dissatisfaction, such as not meeting personal goals. Survival anxiety refers to the fear of the impact of an accident on the reputation of the company or unit. Creation of psychological safety refers to overcoming anxiety when alternative solutions are available. Once people are “unfrozen,” they can begin to change. This “changing” stage enables groups and individuals to move from a less acceptable to a more acceptable set of behaviors [21]. During the changing stage, people begin to learn new concepts, new meanings, and new standards. Activities that aid in making changes include following role models and looking for personalized solutions through trial-and-error learning. According to Schein [20], refreezing is the final stage, in which new concepts and meanings are internalized. Refreezing thus includes the development of a new self-concept and identity and the establishment of new interpersonal relationships. The new way of doing things are institutionalized and become part of the organization's and employees' normal activities. The refreezing step is especially important to ensure that people do not revert to their old ways of thinking or acting [21].

The work of Kurt Lewin dominated the theory and practice of change management for more than 50 years. However, during the 1980s and 1990s, Lewin's three-step model was criticized, especially the third step (refreezing) and a top-down management-driven approach to change. The first criticism is that the final stage of the process should not end up in a rigid state (status quo), but should instead be a part of the ongoing maintenance of culture change. This is because the modern business world is changing at a rapid pace, and there is no time to refreeze after a change process has been implemented [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. The other criticism is that Lewin advocated a top-down, management-driven approach to change [22], [23], [24]. However, Burnes [21] recently reappraised Lewin's model of change. When Lewin wrote of “refreezing,” his concern was about preventing individuals and groups from regressing to their old behaviors. The refreezing stage was not intended as a final, conclusive, and stable state, but as a state from which the following processes of change start [27]. In addition, he did not ignore the importance of bottom-up change, and clearly recognized that the pressure for change comes from many quarters, not just managers and leaders [21].

Understanding the dynamic of organizational change is essential to successfully change occupational safety and health culture. If not, “culture change” is likely to just be a slogan.

4. A case study of safety culture change

Park [28] analyzed methods of preventing noise-induced hearing loss in the workplace. More specifically, her thesis examined changes that occurred over 40 years in one company's hearing conservation program (HCP). This analysis illustrates the process of culture change in improving workplace health and safety according to Lewin's three-step model of unfreezing–changing–refreezing, which was adapted by Schein [20]. A brief history of hearing conservation activities in this workplace is given below.

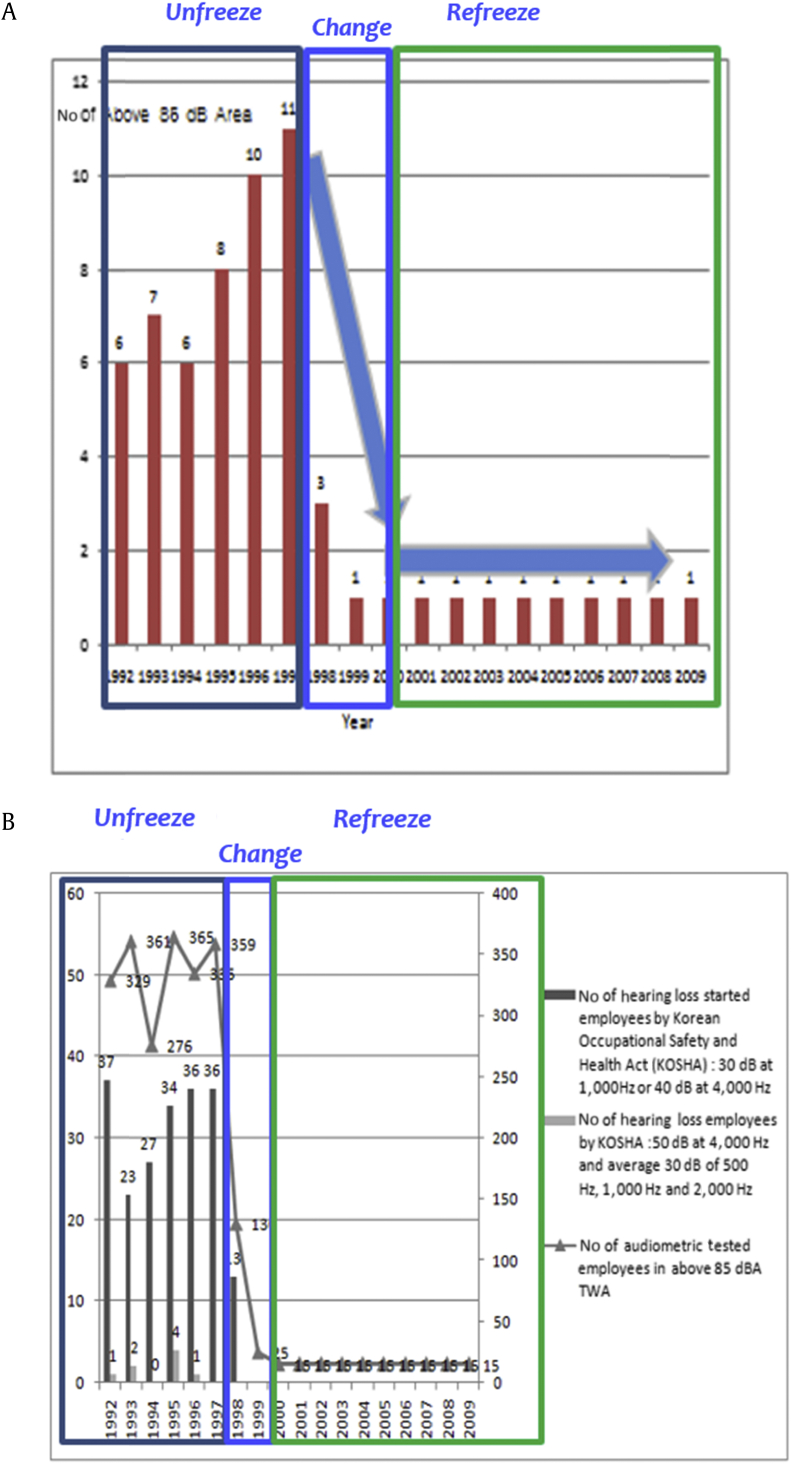

In 1967, a multinational electronics manufacturer established a large factory in Republic of Korea. From 1986 to 1992, mandatory noise monitoring and audiometry were initiated to comply with Korean regulations [29]. From 1992 to 1997, an HCP was implemented to comply with the U.S. Occupational Safety Health Act [30], because the U.S.-based parent company required this as corporate policy. From 1988 to 1999, a company-wide task force team implemented noise control activities using the action learning protocol. Since 2000, there have been continuing improvements in noise reduction. From the viewpoint of the three-stage model of change, the period of 1992 to 1997 corresponds to the unfreezing stage; 1998 to 1999 corresponds to the changing stage; and the period since 2000 corresponds to the refreezing stage [20]. In the unfreezing stage, the motivations for change included the increasing number of workers who experienced noise-induced hearing loss because of the noisy work area, the aging workforce, and the strong demand for an HCP by corporate headquarters in the United States. In the changing stage, a company-wide team with an action learning protocol identified 255 sources of noise, and implemented 148 noise-control measures. This led to a marked reduction in the number of workers in noisy areas. During the refreezing stage, the action learning team developed an awareness of the hazard of noise and skills to prevent noise exposure. The noise reduction status has been maintained continuously since 2000. The action learning team members were “learning by doing” on a weekly basis in their production field. They identified the sources of noise and measured noise themselves after learning how to use a sound pressure level meter. Then, they chose various effective control measures based on consultation with outside noise control professionals and implemented these changes. Various noise control measures were applied, depending on the type of noise sources (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Noisy areas and workers with signs occupational noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). (A) Number of noisy areas from 1992 to 2009 in the workplace. (B) Numbers of workers with definite or probable signs of NIHL from 1992 to 2009 in the workplace. TWA, time-weighted average.

In the stage prior to unfreezing, there were two technical programs—noise monitoring and audiometric testing—in line with the Occupational Safety and Health Act of Korea [29]. The management viewed occupational noise exposure as a hazard, but also as being inevitable for efficient production. During the unfreezing stage, the existing structure began to unfreeze because many workers experienced noise-induced hearing loss, and corporate headquarters in the United States strongly demanded an HCP. Management changed its view, accepting the need to reduce noise exposure. During the changing stage, a company-wide noise-control task force team using the action learning protocol performed a noise survey to identify all sources of noise and to implement noise-control measures. This led to a marked reduction in the number of employees working in noisy areas. Management developed the perspective that noise should be controlled as a risk. During the refreezing stage, all workers, including middle managers, in the production lines served as active monitors of the program. The noise reduction status has been maintained continuously since 2000. A company-wide “buy-quiet” policy was established, in which new machines were required to generate ≤80 dB noise at a distance of 50 cm. A company-wide perception developed that the risk of noise exposure should be prevented.

4.1. Implication of the case study

This study showed that HCPs were initiated by company headquarters, with specific technical and managerial details. However, the study found that the actual control of production-related noise was achieved by action learning. Thus, the two key factors for successful culture change in this case study were leadership and action learning. Leadership is the most important factor for changing the safety culture. Leadership triggered unfreezing, with leaders' attitudes regarding safety issues making a fundamental contribution to culture change. In the present case, the U.S.-based parent company established an HCP as corporate policy. Action learning accomplished cultural transformation.

The concept of action learning was introduced in the 1940s as an educational process, in which participants study their own actions and experiences to improve performance [31]. Action learning is an approach to solving real problems, which involves taking action and reflecting on the results with the support of a team. Revans [31] regarded the conventional methods of instruction in an organization as largely ineffective, leading to the development of action learning, as described by the equation, L = P + Q, where L is learning, P is programmed knowledge, and Q is questioning. Questioning helps create insights about what people see, hear, or feel, and is the cornerstone of the method [31]. The process of action learning involves acquisition of programmed knowledge, colearning in groups, and learning through experiences to solve complex, real-life problems. The key features of action learning are the actual implementation of solutions—not “just talking” about things; learning by doing, or more specifically, learning through reflection on doing. Other key factors are encouragement of an attitude of questioning and reflection and benchmarking or networking good practices [31]. Participatory action-oriented programs such as WISE (Work Improvement in Small Enterprises) have their roots in action learning [32].

The present case shows that leadership was the most important factor in the successful change of safety culture. Leadership triggered unfreezing, and the leaders' attitudes regarding safety issues made a fundamental contribution to culture change. The present study also found that the actual control of production-related noise was achieved by action learning. During the refreezing stage, all workers, including middle managers, in the production lines served as active monitors of the program. Through continuous action learning activities that involved all workers, there was continuous improvement, and the noise level has remained low since 2000. Thus, action learning accomplished cultural transformation. However, safety culture change is both difficult and time consuming. We have observed many more examples of failure than success in Republic of Korea. In these examples of failure, “unfreezing” was begun by the economic loss caused by penalties for noncompliance issued by labor inspection or the impact of a negative reputation caused by serious industrial accidents. However, these companies failed to obtain worker participation and did not achieve cultural changes or make continuous improvements.

5. National preventative safety and health culture

Previous sections have discussed positive safety cultures in the workplace. The following sections will address prevention culture at the national level.

Work in the 21st century is characterized as follows [6], [7], [33]. First, the service and knowledge sectors expanded worldwide. Second, many jobs were lost as a result of mechanization and robotics. Third, the number of small businesses is increasing. In addition, larger companies are reducing their workforces and subcontracting, outsourcing, and offshoring their activities to smaller subcontractors. Thus, almost all new enterprises are small or even smaller microenterprises. Fourth, atypical work schedules, such as shift/night work, and weekend work, are increasing. Fifth, there is increasing inequality among workers, with remarkable increase of precarious workers [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. Informal economy accounts for a large proportion of workers especially in developing countries. However, occupational safety and health legislation often does not apply to such workplaces or, if it does, it is not effectively implemented and enforced [40]. Sixth, the workforce is becoming globalized, with increased worker mobility [41], [42]. There is increasing evidence that migrant workers bear a disparate burden of occupational fatalities, injuries, and illnesses compared with the nonmigrant or native workforces [43]. Finally, the number of older workers is increasing as individuals are living and working longer [44], [45], [46], [47]. For example, Republic of Korea has a lower population of aged individuals than countries in Europe or Japan, but Republic of Korea is the most rapidly aging country in the world [48].

New and emerging issues related to workers' health in the 21st century include new types of work-related disorders, NCDs, and inequality in the availability of occupational health services [8], [9]. Emerging work-related disorders include work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSDs) and cardiovascular disorders (WRCVDs), as well as mental health issues [49]. For example, about two-thirds of compensated occupational claims in Republic of Korea are attributable to WRMSDs [50], [51]. Approximately 600 individuals are compensated yearly for WRCVDs in Republic of Korea [51], [52], and mental ill-health issues due to emotional strains at work are increasing. The incidence of NCDs is gradually increasing because of an aging workforce. Regarding inequality in the availability of occupational health services, only 10–15% of workers in developing countries and 50–90% of workers in most industrialized countries have access to occupational health services [9]. In addition, self-employed persons and workers with precarious employment lack occupational health services in virtually all countries [37], [38], [39]. These new and emerging issues require a prevention culture at the national level.

The ILO developed the Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention, which defined a national preventative safety and health culture as one in which the right to a safe and healthy working environment is respected at all levels, where governments, employers, and workers actively participate in securing a safe and healthy environment through a system of defined rights, responsibilities, and duties, and where the highest priority is accorded to the principle of prevention [53]. ILO Convention No. 187 complements Convention No. 155, which established the basic principles and methodology required for improvements in occupational safety and health management [54]. ILO Convention No. 187 introduced a national policy process for occupational safety and health to prevent accidents and injury to health, by minimizing, so far as is reasonably practicable, the hazards inherent in the working environment. For actions at the national level, the convention mentions implementation and periodic review of the policy, enforcement of relevant laws and regulations, and ensuring coordination among various relevant authorities and bodies. For actions at the enterprise level, the convention addresses employers' duties and responsibilities to ensure that the working environment is safe and without risk to health, and the rights and duties of workers and their representatives.

The goal of the ILO Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention is to promote a preventative safety and health culture through the application of an occupational safety and health management system approach at a national level. This convention applies an occupational safety and health management system approach. The key concept is to pursue continual improvement in occupational safety and health performance by applying the Plan–Do–Check–Act cycle [55]. The Convention prescribes how national policy, national systems, and national programs should be designed to promote continuous improvements in occupational safety and health.

The convention's approach at the national level was endorsed by the Seoul Declaration at the 18th World Congress on Safety and Health at Work in 2008 [56], and by the Istanbul Declaration of 2011 [57]. According to the Seoul Declaration, “promoting high levels of safety and health at work is the responsibility of society as a whole, and all members of society must contribute to achieving this goal by ensuring that priority is given to occupational safety and health in national agendas and by building and maintaining a national preventative safety and health culture. The continuous improvement of occupational safety and health should be promoted by a systems approach to the management of occupational safety and health, including the development of a national policy taking into consideration the principles in the ILO Convention (No. 155)” [56]. The adoption of the Istanbul Declaration by 33 ministers on the occasion of the Summit of Ministers of Labour for a Preventative Culture in September 2011 was another important milestone in recognizing the importance of active involvement of employers and workers in achieving prevention and compliance [57].

The International Social Security Association (ISSA), a co-organizer of the 18th World Congress with ILO and the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA) in 2008, set up a prevention culture section and issued ISSA prevention guidelines. These guidelines link risk management, health promotion, and return-to-work measures as a three-dimensional approach to prevention, and highlight the important role of social security institutions in building and maintaining a prevention culture [58].

6. Creation of a prevention culture

The concept of a prevention culture is implicitly based on the concept of a safety culture. Both utilize a cultural approach. A safety culture aims to reduce work-related risks, whereas a prevention culture aims to reduce both work-related and nonwork-related risks (Table 1). Safety culture is addressed mainly to the workplace level, whereas prevention culture is addressing the societal or national level as well. The targets of a safety culture are mainly industrial accidents and work-related diseases, although safety culture targets NCDs in some industries (e.g., firefighting); the targets of a prevention culture are NCDs, industrial accidents, and work-related diseases including mental ill health [8]. In a safety culture, the emphasis is on the protection of health, whereas a prevention culture emphasizes both the protection and promotion of health [59], [60]. In a safety culture, the covered population consists mainly of employees in high-risk industries, such as the nuclear and petrochemical industries and mass transportation, and small businesses with less risk, whereas a prevention culture includes all workers, including those who are self-employed and precarious workers at all workplaces. A competent authority, such as the Ministry of Labor, is involved in safety culture, whereas a prevention culture is built and maintained by the government as a whole, involving relevant ministries to ensure that workers' health is considered a priority in the national agenda [59], [60]. For example, precarious workers, both those who are employed part time and those working as small subcontractors, are usually regarded as outside the occupational health service system [9], [40]. Protecting and promoting their overall health requires cooperation between the Ministries of Labor and Health at the national level, as well as cooperation between the workplace and the community health center at the local level.

Table 1.

Comparisons of prevention and safety cultures

| Prevention culture | Safety culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension | National level and workplace level | Workplace level |

| Aim | Reduce work-related and nonwork-related risk | Reduce work-related risk |

| Target | Accident + WRD + NCD | Accident + WRD |

| Activities | Health protection + health promotion | Health protection |

| Coverage | All workers | Employees |

| Places | All workplaces | High-risk industries |

| Agent | Ministry of Labor, Ministry of Health, and other government entities | Ministry of Labor |

NCD, noncommunicable disease; WRD, work-related disease.

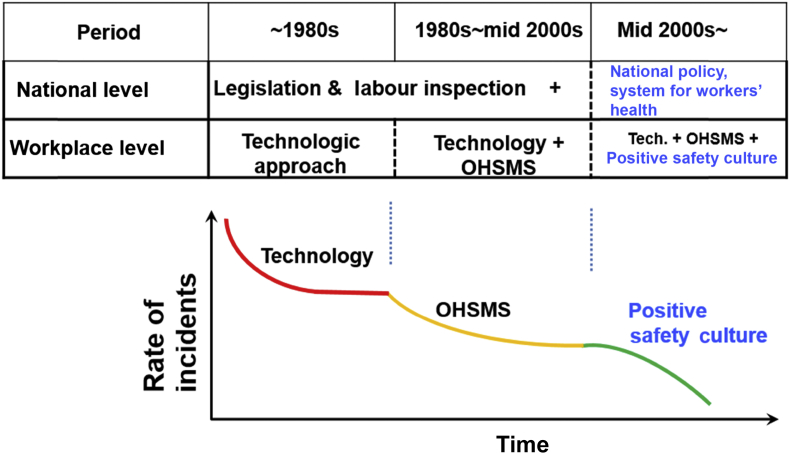

Fig. 3 shows a schematic layout of the change in the rate of safety incidents that accompanied changes in technology, the introduction of an occupational safety and health management system, and the development of a positive safety culture at the national and workplace levels. Technological improvements, compliance with regulations and labor inspections, and introduction of an occupational safety and health management system are required to reduce risks in the workplace. A positive safety culture developed through managed cultural change is crucial for further risk reduction. Establishment of policies and a system for workers' health at the national level is crucial for promoting a prevention culture.

Fig. 3.

Evolution to a prevention culture. OHSMS, occupational health and safety management system.

In conclusion, to promote a prevention culture, actions are needed at both the workplace and national levels. The workplace level requires technological improvements, such as engineering controls, compliance with regulations, and introduction of occupational safety and health management systems, as well as managed culture change to achieve a positive safety culture. The national level requires that priority be given to workers' health in the national agenda, and the need for a national approach to workers' health involving the government as a whole, thus promoting a prevention culture.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hale A.R., Hovden J. Management and culture: the third age of safety. In: Feyer A.-M., Williamson A., editors. Occupational injury: risk, prevention and intervention. Taylor & Francis; London (UK): 1998. pp. 129–166. [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Labour Organization (ILO) Office; Geneva (Switzerland): 2009. Information on decent work and a health and safety culture [Internet]http://www.ilocarib.org.tt/portal/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1138&Itemid=1141 [cited 2015 Sep 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Nuclear Safety Advisory Group (HSC) International Atomic Energy Agency; Vienna (Austria): 1986. Summary report on the post-accident review meeting on the Chernobyl accident, Safety Series No. 75-INSAG-1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health and Safety Commission (HSC) HSC; London (UK): 1993. ACSNI Study Group on Human Factors. 3rd Report: Organizing for Safety. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yau B. 2014. Occupational safety culture index – Measuring the community and employees awareness, attitude and knowledge towards workplace safety and health in Hong Kong [power point slides] XX World Congress on Safety and Health at Work 2014 – Global Forum for Prevention. Frankfurt (Germany) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neira M. 2010. Healthy workplaces: a model for action [Internet] [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/launch_hwp_22april.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paltiel F.L. Shifting paradigms and policies. In: Stellman J.M., editor. International Labour Office; Geneva (Switzerland): 2012. http://www.iloencyclopaedia.org/part-iii-48230/work-and-workers (Encyclopedia of occupational health and safety, online ed. [Internet]). Chapter 24. Work and workers, Part III. Management and policy. [cited 2015 Sep 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global strategy on occupational health for all: the way to health at work. In: Recommendation of the second meeting of the WHO Collaborating Centres in Occupational Health, 11–14 Oct 1994, Beijing, China [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization. 1995 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/globstrategy/en/index6.html.

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Geneva (Switzerland): 2013. The WHO Global Plan of Action on Workers’ Health (2008–2017): Baseline for Implementation [Internet]http://www.who.int/occupational_health/who_workers_health_web.pdf [cited 2015 Sep 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health and Safety Executive (HSE) HSE Books; Suffolk (UK): 2005. Research report 367. A review of safety culture and safety climate literature for the development of the safety culture inspection toolkit. Report No.: 367. [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Atomic Energy Agency. Application of the management system for facilities and activities. Safety Guide Series No. GS-G-3.1, 2006 [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www-pub.iaea.org/mtcd/publications/pdf/pub1253_web.pdf.

- 12.Hudson PTW, Parker D, Lawton R, Verschuur WLG, van der Graaf GC, Kalff J. The hearts and minds project: creating intrinsic motivation for HSE. SPE International Conference on Health, Safety and Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production, 26-28 June 2000, Stavanger, Norway. Stavanger (Norway): Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2000.

- 13.Fleming M. Safety culture maturity model. Offshore Technology Report 2000/049 [Internet]. Norwich (UK): Health and Safety Executive Books. 2001 [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: www.hse.gov.uk/research/otopdf/2000/oto00049.pdf.

- 14.Parker D., Lawrie M., Hudson P. A framework for understanding the development of organisational safety culture. Saf Sci. 2006;44:551–562. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seel R. Culture and complexity: new insights on organisational change. Org People [Internet] 2000 [cited 2015 Sep 21];7:2–9. http://www.new-paradigm.co.uk/culture-complex.htm 2000. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao T. Speech at the Chinese Communist Party's national conference on propaganda work [Internet]. 1957 [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-5/mswv5_59.htm.

- 17.Lewin K. Frontiers in group dynamics. Concept, method and reality in social science; equilibrium and social change. Human Relations. 1947;1:5–41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schein E.H. Models and tools for stability and change in human systems. Reflections. 2002;4:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schein E.H. 3rd ed. Prentice-Hall; London (UK): 1988. Organizational psychology. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schein E.H. Kurt Lewin's change theory in the field and in the classroom: notes towards a model of management learning. Syst Pract. 1996;9:27–47. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burnes B. Kurt Lewin and the planned approach to change: a re-appraisal. J Manage Stud. 2004;41:977–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson P. Paul Chapman Publishing; London (UK): 1994. Organizational change: a processual approach. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanter R.M., Stein B.A., Jick T.D. Free Press; New York (NY): 1992. The challenge of organizational change. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson D.C. Routledge; London (UK): 1992. A strategy of change. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotter J. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Bus Rev. 1995;73:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stickland F. Routledge; London (UK): 1998. The dynamics of change: insights into organisational transition from the natural world. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longo R. Is Lewin's change management model still valid? HR Professionals [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://rosariolongo.blogspot.com/2011/05/is-lewins-change-management-model-still.html.

- 28.Park M. Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University; Seoul (Republic of Korea): 2013. Hearing conservation culture change and noise control program implementation; a reflection on 40 years of hearing conservation history at a multinational company. Doctoral thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korean Ministry of Labor (KMOL) 2003. Regulation of Occupational Health Standard, KMOL Administrative Law 195 [Internet]http://www.law.go.kr/DRF/MDRFLawService.jsp?OC=molab&ID=7363 [cited 2015 Sep 16]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Occupational Safety and Health Administration Occupational noise exposure: Hearing conservation amendment, Final Rule, 29CFR1910.95. Fed Regist. 1983;48:9738–9785. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Revans R. Blond and Briggs; London (UK): 1980. Action learning: new techniques for action learning. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thurman J.E., Louzine A.E., Kogi K. International Labour Office; Geneva (Switzerland): 1988. Higher productivity and a better place to work: practical ideas for owners and managers of small and medium-sized industrial enterprises. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luxembourg Declaration on Workplace Health Promotion in the European Union [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.enwhp.org/fileadmin/rs-dokumente/dateien/Luxembourg_Declaration.pdf.

- 34.Kalleberg A.L. Nonstandard employment relations: part-time, temporary and contract work. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:341–365. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalleberg A.L., Reskin B.F., Hudson K. Bad jobs in America: standard and nonstandard employment relations and job quality in the United States. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;65:256–278. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinlan M., Mayhew C., Bohle P. The global expansion of precarious employment, work disorganization, and consequences for occupational health: a review of recent research. Int J Health Serv. 2001;31:335–414. doi: 10.2190/607H-TTV0-QCN6-YLT4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsurugano S., Inoue M., Yano E. Precarious employment and health: analysis of the Comprehensive National Survey in Japan. Ind Health. 2012;50:223–235. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoue M., Tsurugano S., Nishikitani M., Yano E. Full-time workers with precarious employment face lower protection for receiving annual health check-ups. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55:884–892. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim M.H., Kim C.Y., Park J.K., Kawachi I. Is precarious employment damaging to self-rated health? Results of propensity score matching methods, using longitudinal data in South Korea. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1982–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rantanen J. Occupational health services for the informal sector. Africa Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety, No. 2 [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.ttl.fi/en/publications/electronic_journals/african_newsletter/african_archives/Documents/african_newsletter2_2009.pdf.

- 41.Hogstedt C., Wegman D.H., Kjellstrom T. The consequences of economic globalization on working conditions, labor relations, and workers' health. In: Kawachi I., Wamala S., editors. Globalization and health. Oxford University Press; New York (NY): 2007. pp. 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawachi I. Globalization and workers' health. Ind Health. 2008;46:421–423. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.46.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shenker M. A global perspective of migration and occupational health. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:329–337. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casey CL. Safer and healthier at any age: strategies for an aging workforce. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [Internet] Georgia (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012. [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2012/07/19/agingworkforce/.

- 45.European Network of Heads of PES . 2011. Meeting the challenge of Europe’s ageing workforce-the Public Employment Service response [Internet]http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=7301&langId=en [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin J., Durand M. 2006. Older workers: Living longer, working longer. DELSA Newsletter Issue 2 [Internet]. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.www.oecd.org/social/family/35961390.pdf [cited 2015 Sep 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 47.Community Business . 2010. Ageing: impact on companies in Asia. Community business [Internet] [cited 2015 Sep 4]. Available from: http://www.communitybusiness.org/images/cb/publications/2010/Ageing.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lowe-Lee F. Is Korea ready for the demographic revolution? The world's most rapidly aging society with the most rapidly declining fertility rate [Internet]. The Korea Economic Institute of America. 2009 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.keia.org/sites/default/files/publications/04Exchange09.pdf.

- 49.Harnois G., Gabriel P. World Health Organization and International Labour Organization; Geneva (Switzerland): 2000. Mental health and work: impact, issues and good practices. In: Nations for Mental Health [Internet] [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/712.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang D., Kim Y., Lee Y., Koh S., Kim I., Lee H. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Korea provoked by workers' collective compensation claims against work intensification. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2014;26:19. doi: 10.1186/2052-4374-26-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency . 2014. Statistics on the compensated industrial accidents cases [Internet]http://www.kosha.or.kr/board.do?menuId=554 [cited 2015 Sep 20]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng Y., Park J., Kim Y., Kawakami N. The recognition of occupational diseases attributed to heavy workloads: experiences in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85:791–799. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.International Labour Organization. Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention (No. 187) [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE: C187.

- 54.International Labour Organization. Occupational Safety and Health Convention (No. 155) [Internet]. 1981 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE: C155.

- 55.International Labour Organization (ILO). The ILO Guidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems (ILO-OSH 2001) [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_107727.pdf.

- 56.Seoul Declaration on Safety and Health at Work [Internet]. Seoul(Republic of Korea): Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency. 2008 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.seouldeclaration.org.

- 57.Istanbul Declaration on Safety and Health at Work [Internet]. Istanbul (Turkey). 2011 [cited 2015 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.iali-aiit.org/resources/istanbul-declaration.pdf.

- 58.International Social Security Association . 2015. Social security and a culture of prevention: a three-dimensional approach to safety and health at work [Internet] [cited 2015 Dec 17]. Available from: http://www.issa.int/topics/occupational-risks/issa-publications. [Google Scholar]

- 59.European Commission . 2014. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on an EU Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work 2014–2020 [Internet]http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52014DC0332 [cited 2015 Sep 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 60.International Labour Organization . 2014. Creating safe and healthy workplaces for all [Internet]http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2014/ILO-safe_and_healthy_workplaces.pdf [cited 2015 Sep 16]. Available from: [Google Scholar]