Abstract

How organisms adapt to new environments is of fundamental biological interest, but poorly understood at the genetic level. Chemosensory systems provide attractive models to address this problem, because they lie between external environmental signals and internal physiological responses. To investigate how selection has shaped the well-characterized chemosensory system of Drosophila melanogaster, we have analysed genome-wide data from five diverse populations. By couching population genomic analyses of chemosensory protein families within parallel analyses of other large families, we demonstrate that chemosensory proteins are not outliers for adaptive divergence between species. However, chemosensory families often display the strongest genome-wide signals of recent selection within D. melanogaster. We show that recent adaptation has operated almost exclusively on standing variation, and that patterns of adaptive mutations predict diverse effects on protein function. Finally, we provide evidence that chemosensory proteins have experienced relaxed constraint, and argue that this has been important for their rapid adaptation over short timescales.

Fruit flies gain valuable information about their environment by sensing chemicals. Here, Arguello et al. show strong signals of recent selection on the chemosensory system of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, consistent with the adaptation of populations to their local chemical environment.

Fruit flies gain valuable information about their environment by sensing chemicals. Here, Arguello et al. show strong signals of recent selection on the chemosensory system of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, consistent with the adaptation of populations to their local chemical environment.

Understanding how organisms adapt to new environments—local adaptation—is of fundamental biological interest. While there is extensive evidence for local adaptation based on phenotypic data, its genetic basis in natural populations is poorly understood1. Identifying the precise molecular change(s) that underlie the selected trait(s) remains challenging, as does answering general questions regarding the mutational sources (de novo, standing variation) and overall frequency of adaptive evolution2,3,4. Addressing these challenges demands both an in-depth characterization of population genetic variation and a detailed molecular understanding of the biological system under selection.

A particularly interesting question is how neural sensory perception is altered during local adaptation. Sensory systems interact directly with the environment, and are responsible for translating external visual, chemical, mechanical and thermosensory signals into changes in physiology and behaviour. The match between perceptual ability and behavioural outputs carries numerous fitness consequences, for example, the ability to locate food and breeding sites, avoid danger, identify mates and regulate body temperature. Because new environments can present novel stimuli, it is suspected that many sensory systems have experienced strong selective pressures to evolve quickly.

The chemosensory systems of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, underlying olfaction and gustation, provide attractive models to address the genetic basis of local adaptation. Laboratory studies have defined many molecular, physiological and anatomical properties of D. melanogaster's chemosensory circuits5,6,7,8. In nature, the environmental chemical universe relevant for D. melanogaster's survival is vast, encompassing both volatile and non-volatile signals. These can indicate sources of nutrition, oviposition sites and dangers such as poisonous microbes9 and predators10, as well as pheromones that control mating, aggression and aggregation behaviours11,12.

Environmental chemicals are detected in D. melanogaster by chemosensory neurons housed within porous cuticular hairs called sensilla5. Olfactory sensilla, which detect volatile chemicals, are located on two head appendages, the antenna and maxillary palp. Gustatory sensilla are distributed more widely, on the labellum of the proboscis, leg tarsi, wing margins and, in females, the ovipositor. Chemical detection by these sensory structures requires their direct (or close) contact with a substrate. The Drosophila larva also possesses a number of specialized olfactory and gustatory organs5.

The vast majority of receptors that detect chemical signals and convert ligand binding into neural activity belong to one of three repertoires, each comprising ∼60 genes: odorant receptors (ORs) and gustatory receptors (GRs), which encode related families of seven transmembrane domain ion channels5, and ionotropic receptors (IRs), which are distantly related to ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs)13. Olfactory organs express ORs and a subset of IRs (∼15 genes; termed ‘olfactory IRs'14), with most olfactory sensory neurons expressing a single ‘tuning' OR or IR that is the principal determinant of the odour-response profile. Gustatory sensory neurons express GRs and the complementary subset of ∼45 ‘non-olfactory' IRs, with individual neurons often expressing multiple GR and/or IR genes8,15,16. In addition to these transmembrane proteins, perireceptor proteins of the odorant-binding protein (OBP) family are secreted into the sensillum lymph that bathes chemosensory neuron dendrites. Despite their name, OBPs (encompassing ∼50 genes) are expressed in both olfactory and gustatory organs, usually in specific subsets of sensilla, where they are thought to contribute to chemosensory signal transduction by solubilizing, transporting and/or protecting chemical ligands from degradation within the aqueous lymph before reaching the sensory membranes17.

Previous comparative studies have highlighted the evolution of chemosensory gene families (Ors, Grs, Irs and Obps) as ‘dynamic', in terms of high protein divergence, expression differences and family member turnover15,18,19,20. Although these changes have occasionally been associated with ecological differences between species18,20,21, very little is currently known about the adaptive (and non-adaptive) function that these changes might have provided. Moreover, almost nothing is known about within-population variability for these families, as most evolutionary investigations have focused on inter-species comparisons. At these deeper timescales (that is, many millions of years), the short-lived DNA-based signals of selection are largely eroded22, and the accumulation of non-selected substitutions complicates the identification of the beneficial mutation(s).

To gain a broad understanding of the evolutionary forces governing the D. melanogaster chemosensory families and to identify specific targets of selection, we have analysed the genome-wide data (single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), indel and larger copy number variants (CNVs)) from the recently sequenced global diversity lines (GDLs)23. These 84 lines encompass an ancestral-like African D. melanogaster population (Zimbabwe) and four derived populations from North America (Ithaca, USA), Europe (Netherlands), Asia (Beijing) and the South Pacific (Tasmania). The African ancestral population of D. melanogaster is believed to have expanded ∼60,000 years ago and subsequent lineages have inhabited ecologically diverse localities world wide24. These genomic samples are therefore well suited for testing how local adaptation has impacted the chemosensory system, and to provide the first view into how these systems vary among distinct populations.

By placing genomic analyses of chemosensory protein families in the context of those of other large families, we demonstrate that chemosensory proteins as a group do not display exceptional rates of adaptive divergence. By contrast, more recent signals of historical selection arising from within-species analyses reveal striking evidence for selection in chemosensory protein families. Moreover, these analyses indicate that standing variation has provided the primary substrate for selection, and that this variation likely has diverse effects on protein function.

Results

Molecular divergence of large protein families

We were interested in quantifying the extent to which chemosensory proteins experience adaptive evolution over short time spans relative to other regions of D. melanogaster's genome. Because the main chemosensory gene families are large (∼60 members each) and often tandemly arranged, we used all other large multigene families (≥20 members) for our standard of comparison. Protein family definitions were based on PANTHER Database classifications25, and encompass 40 families (Supplementary Table 1) with known or predicted roles in diverse biological processes such as immune defence and metabolism.

Like chemosensory genes, members of these multigene families are broadly distributed across D. melanogaster's major chromosome arms and recombination environments (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, the use of protein families provides a more natural comparison across groups of genes with varying degrees of functional overlap than a random set of loci.

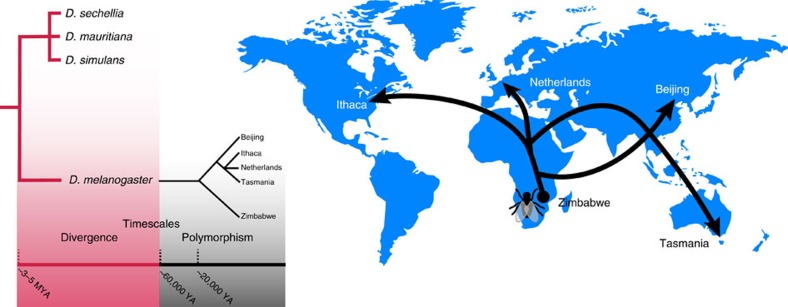

Our polymorphism data originated from the GDLs, for which there are validated calls for ∼5.8 million SNPs and 970,000 small indels23. In addition, we have incorporated CNV calls consisting of 2,221 duplications, 56,562 deletions and 3,850 insertions26. These polymorphism and divergence data allow us to test models of adaptive evolution at two different timescales, and provide information about adaptive changes that occurred as D. melanogaster was forming as a species, as well as local adaptation during its recent global expansion (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. D. melanogaster's recent global expansion.

Left: tree schematic illustrating D. melanogaster's relationship with its most closely related species, and the relationship between the five D. melanogaster populations from the global diversity lines. The most recent common ancestor shared with the D. simulans species trio was ∼3–5 million years ago (MYA). The non-African populations are estimated to have branched off ∼20,000 years ago (YA), and it is believed that the African ancestral population of D. melanogaster began to expand ∼60,000 YA. The separation between the two trees (red versus black) emphasizes the two timescales examined in this study. Right: cartoon representation of the expansion of the five populations from Africa around the globe.

Chemosensory genes are not outliers for adaptive divergence

We first investigated the occurrence of relatively old signals of selection within these large protein families along the branch leading to extant D. melanogaster after it split from its last common ancestor with the D. simulans triad (∼3–5 Myr ago27; Fig. 1). In particular, we tested whether chemosensory genes experienced a disproportionate number of positively selected protein changes along this branch when compared with the other large families. Central to our tests were the numbers of silent and replacement polymorphism (PS and PR, respectively) and silent and replacement substitutions (DS and DR, respectively). These can be compared through contingency tables, referred to as McDonald-Kreitman (MK) tables28. If positive selection has acted on protein structures, we would expect a significant excess of replacement changes between species (that is, an excess DR/PR relative to DS/Ps). Under a neutral model, we would expect equal ratios (DR/PR=Ds/Ps). From these data, it is also possible to estimate the fraction of amino-acid differences that were fixed between species by positive selection2,29.

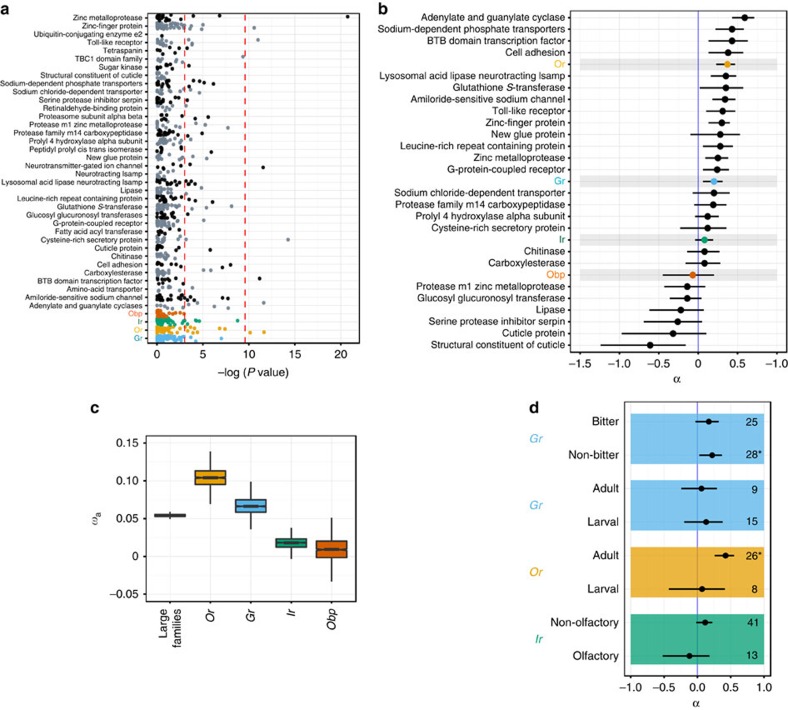

We calculated three related summary statistics based on our MK tables for the 29 large protein families having the most complete data: individual gene MK test P values28, a summary of the MK tests that controls for sparse data referred to as the direction of selection (DoS30), and the fraction of protein changes fixed by positive selection, α (refs 2, 29). Although we identified a small number of individual chemosensory genes as potential targets of positive selection (before and after correcting for multiple tests; Fig. 2a; Supplementary Data 1), the chemosensory families do not uniformly have a higher frequency of significant MK tests than the other large protein families nor are their α values concentrated in the upper tail (Fig. 2b; similar results were observed for DoS estimates; Supplementary Fig. 2). These data indicate that the chemosensory genes, as a group, are not outliers for having experienced adaptive divergence.

Figure 2. Adaptive divergence analyses.

(a) Manhattan Plot for large protein family MK test P values. Left-most red line denotes the 5% significance level; right-most red line denotes Bonferroni correction significance threshold. (b) Rank-ordered plot of the fraction of adaptive substitutions (α) inferred across the large protein families. Coloured spheres represent the maximum likelihood α estimates, with horizontal lines indicating the 2 units of log(L) confidence intervals. The total number of families included in the analyses was reduced to 29 due to data requirements. (c) Box plot comparing ωa (α divided by neutral diversity) among the chemosensory genes and the pooled non-chemosensory large protein families. The boxes show the interquartile range and bars extend to the highest and lowest outliers. (d) Comparisons of α between functional groupings within gene families. Numbers along the right margin indicate the number of genes included in the analyses, with asterisks indicating significantly positive α estimates (P<0.05; log likelihood ratio test). Black spheres represent the maximum likelihood α estimates, and horizontal lines indicate the 2 units of log(L) confidence intervals.

Adaptive divergence within chemosensory families

Within the four chemosensory families, Ors and Grs consistently carry the strongest family-wide signals of interspecific adaptive change. Notably, the confidence intervals for the Or and Gr α estimates are relatively small and do not overlap zero (Fig. 2b); in addition, Ors possess the fifth highest estimated α value among large protein families. By contrast, the Irs and Obps provide α estimates that are compatible with neutrality (confidence intervals overlap zero; Fig. 2b). A consistent result is obtained if we scale α by the rate of synonymous substitution (ωa), indicating that the observed trend among chemosensory loci, as well as the comparison of chemosensory loci and other large protein families, is not driven by systematic differences in the effectively neutral substitution rates among families31 (Fig. 2c).

A set of 17–21 genes (10 Ors, 4 Grs, 6 Irs and 1 Obp) shows an excess of nonsynonymous divergence before correcting for multiple tests, depending on whether the substitutions are polarized along D. melanogaster's branch (Supplementary Data 1). One of the Ors (Or67a) was independently identified as a target of selection within a more limited study of this family32. While caution must be applied to this set, as only two are significant after Bonferroni correction (Or33c and Or49a), several encode receptors with behaviourally relevant ligands. For example, OR49a is narrowly tuned to a Leptopilina wasp semiochemical, and is necessary for avoidance of this parasitoid10. A second intriguing candidate is GR63a, which is part of a receptor for CO2, a potent, but species-specific trigger of avoidance behaviours33. These data provide potential inroads for between-species studies of functional differences, to permit rigorous tests of adaptive protein changes.

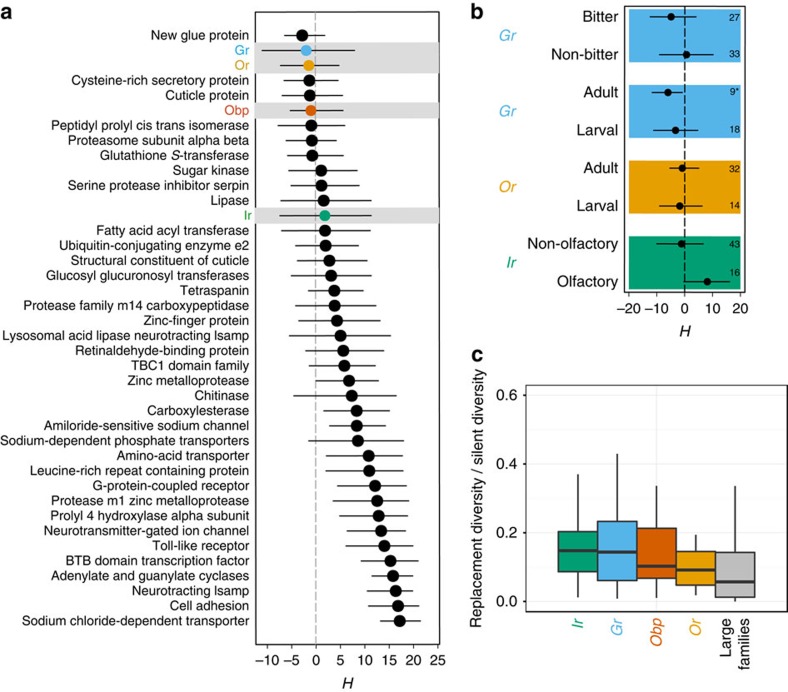

Within the Ir family, five of the six genes that individually carry signals of adaptive evolution are from the non-olfactory subfamily, many of which are expressed in taste organs8,15. This subfamily has experienced more extensive between-species changes than the olfactory Irs, many of which are deeply conserved in insects15. We therefore estimated α separately for the two Ir subfamilies to test whether this accelerated divergence was the result of relaxed constraint or adaptive protein changes. Indeed, the non-olfactory subfamily carries a positive α estimate, but its confidence interval does narrowly overlap zero (0.116, −0.01:0.23), while the olfactory subfamily possesses a negative α estimate (−0.12, −0.52:0.18; Fig. 2d).

To explore whether other subgroups of chemosensory gene families display different divergence properties, we additionally examined the Gr and Or α estimates with respect to the subsets of these genes expressed only in the adult or larva, and for the subset of Gr genes that encode receptors implicated in bitter tastant detection5,7 (sample size limits other types of categorization). Adult-specific Ors have a significantly positive α (0.42, 0.26:0.55; log likelihood ratio test: P<0.0001), in contrast to those expressed only in the larva (Fig. 2d). A similar relationship was not observed for the Grs. However, there is an indication that the receptors outside of the bitter clade (including those detecting pheromonal and sweet ligands) are more likely to have experienced adaptive divergence, as their α is significantly positive (0.22, 0.03:0.37; log likelihood ratio test: P<0.05), while the bitter clade's confidence interval overlaps zero (0.17, −0.03:0.32).

Together, these between-species analyses provide a broader protein family-wide context to interpret chemosensory protein divergence than has previously been available. Importantly, our results suggest that chemosensory families did not contribute disproportionately to adaptive evolution within the ancestral lineage leading to extant D. melanogaster. These findings support a more tempered view than has often been taken, in which chemosensory protein families are presented as ‘token' examples of rapid adaptive divergence. Consistent with previous results2,34, our data indicate that D. melanogaster's protein-coding genome as a whole experienced a large amount of adaptive divergence; chemosensory proteins fit within this greater trend. In this context, our analyses provide novel insights into other large protein families, and highlight those that warrant further investigation for between-species differences. Interestingly, the ‘adenylate and guanylate cyclase' family, which has the highest α value (0.59, 0.43:0.71; log likelihood ratio test: P<<0.01; Fig. 2b), includes genes implicated in behavioural responses to gustatory stimuli and hypoxia35.

Chemosensory families and rapid local adaptation

We next tested for selective events that have occurred over the past few thousand years within D. melanogaster populations. Do similar evolutionary patterns hold across this shallower timescale, and how might the global expansion out of Sub-Saharan Africa into new ecological niches impact the chemosensory protein families?

A common approach to scanning the genome for between-population signals of selection is to test for significant differences in allele frequencies among population samples (Fst-based approaches). Differences in the presence or strength of positive selection across populations can result in changes in allele frequencies, thereby elevating values of Fst. We applied two Fst-based approaches: a Bayesian model-based approach36 and a demographically informed empirical-distribution approach.

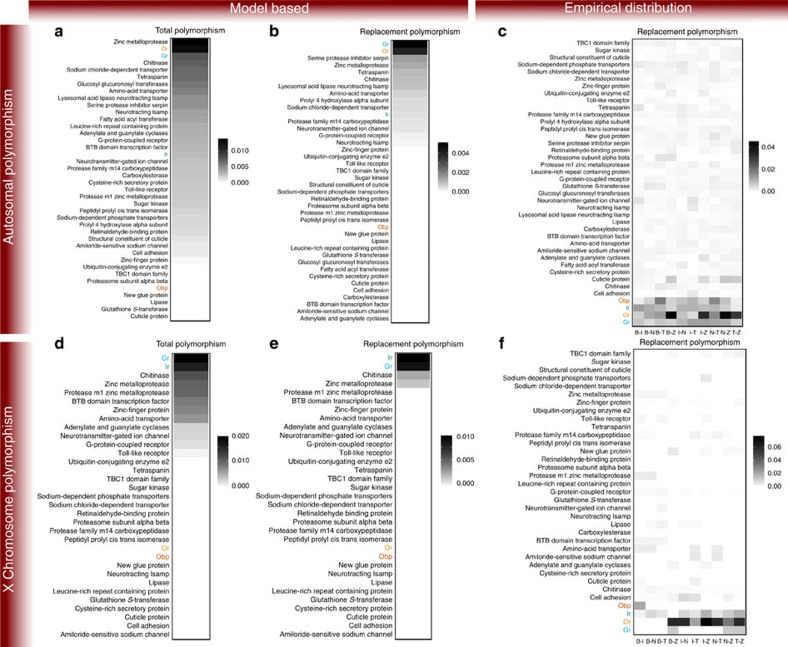

As our initial interest was in the relative rankings among the large protein families, we summarized the results from the Bayesian analysis as the fraction of SNPs identified as outliers, scaled by the total number of SNPs within each family. Due to the varying effective population sizes, these analyses were carried out separately for the autosomes and the X chromosome. The proportion of outlier SNPs for Ors and Grs on autosomes (0.013 and 0.009, ranking second and third, respectively), and for Grs and Irs on the X chromosome (0.021 and 0.018, ranking first and second) are among the largest (Fig. 3a,d). When focusing exclusively on protein-changing SNPs, the chemosensory families, except for the Obps, rise further in the rankings for the autosomal set (Grs are first (0.005), Ors are second (0.004) and Irs are eleventh (0.0005); Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Chemosensory families show strong population differentiation (Fst).

Heatplots summarizing the fraction of loci identified as positive selection candidates. The left two columns (a,b,d,e) display results from a model-based approach (BayeScan), summarizing either the total data (total polymorphism) or data for replacement polymorphism only (replacement polymorphism). The third column (c,f) displays results from an empirical-distribution outlier approach, using the 1% Fst tail as the cutoff. The top row displays results for the autosomal data; the bottom row displays data for the X chromosome. Values shown in the scale bars are the total number of outliers identified in the given analyses divided by the total number of SNPs in the same analysis.

These model-based Fst results are consistent with the contribution of the nonsynonymous Fst values in the extreme tails of the genome-wide empirical Fst distributions. If positive selection has operated disproportionally on the sensory protein families, we would expect there to be an enrichment of these genes in the upper tail of the Fst distribution. We calculated the 1% upper tails from all five pair-wise population nonsynonymous Fst distributions, and computed the number of nonsynonymous polymorphisms falling within these tails for each of the protein families. We then scaled these counts by the total number of nonsynonymous polymorphisms within each protein family. Notably, the chemosensory genes have a much higher proportion of protein-changing SNPs in the upper tails of the Fst distribution than most other protein families (Fig. 3c,f). As expected, all loci identified through the Bayesian analysis were identified within the 1% data set.

Our results from examining the empirical distribution of Fst are robust across both the autosomal and the X-chromosome loci, and are independent of the particular threshold used for identifying the tail (Fig. 3). Furthermore, we used coalescent simulations to explore how likely the observed Fst values in the extreme tails would be observed under selectively neutral models that include reasonable demographic parameters. Encouragingly, for most pair-wise comparisons, our values demarking the empirical 1 and 5% tails superseded those of the simulations (several Beijing scenarios are exceptions; Supplementary Data 2). These simulation results reinforce the conclusions that the extreme Fst tails are enriched for targets of positive selection and that chemosensory protein families are among the most quickly adapting proteins in the D. melanogaster genome among populations.

Integrating F st outliers with chemosensory protein function

Functional analyses of chemosensory receptors, in particular the ORs, have revealed a range of breadths of tuning profiles, from receptors that respond to only a single compound, to those that detect many chemically diverse molecules37,38. We asked whether the tuning breadth of the receptors has a relationship with their rate of between-population differentiation. One might suspect, for example, that broadly tuned receptors could more readily be selected upon, as a result of having a larger pool of potential ligands. Conversely, narrowly tuned receptors may be more crucial to the fly's fitness and thus be under stronger purifying selection. We used published receptor specificity data (measured by lifetime kurtosis) for a majority of ORs39. We then regressed Fst values onto these receptor specificity measures. We found a significantly negative correlation between Fst and the breadth of tuning (−0.24; P=0.03), suggesting that broadly tuned receptors differ between D. melanogaster populations more than narrowly tuned receptors (Supplementary Fig. 3). Although additional substantiating physiological data are needed, this observation might guide future investigations of the relationship between the specificities of receptors and their rates of evolution.

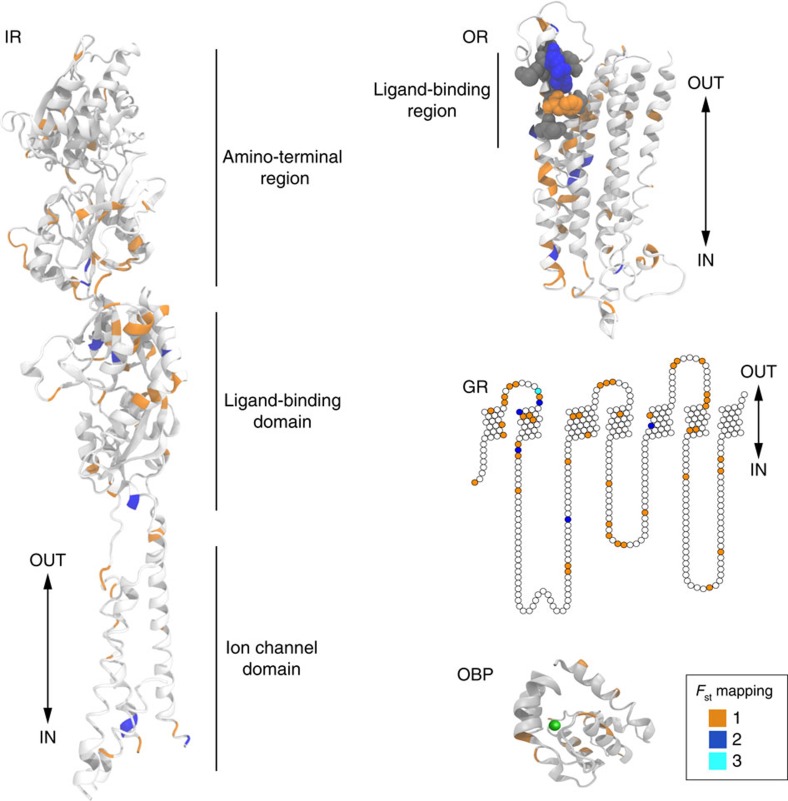

IRs, ORs and GRs are thought to be ligand-gated ion channels, whose binding of extracellular chemicals induces gating of a transmembrane pore40. To investigate whether selection candidate residues cluster within functional domains of these receptors, we mapped the top amino-acid-changing candidate SNPs (1% Fst outliers) onto reference protein models. The predicted domain organization of IRs is best understood because of their homology to iGluRs, and we found that many of the candidate residues are located within the ligand-binding domain (Fig. 4). However, many also map to the amino-terminal region (which has an important but unclear function in IRs6) and the ion-channel domain (Fig. 4). The three-dimensional structure of the heptahelical OR and GR ion channels is unknown, but an OR protein model has been built using amino-acid coevolution patterns and secondary structure predictions41. Within this model, many candidate residues map within the N-terminal half of the protein, which is thought to encompass the ligand-binding site (Fig. 4), but others are located more C-terminally (in transmembrane helices and intra- and extracellular loops) where ion conduction may occur42 (Fig. 4). A similar distribution was found for candidate sites mapped onto a two-dimensional representation of a GR (Fig. 4). These analyses predict that sites under positive selection can have diverse functional influences on these receptors, including both their ligand-binding and ion conduction properties. For OBPs, sites were mapped onto the X-ray crystal structure of LUSH43, revealing their location both in the internal ligand-binding cavity and on the external surface (Fig. 4). This distribution suggests that these sites could have either direct or indirect effects on interactions of these proteins with chemical cues.

Figure 4. Candidate protein-altering SNPs on chemosensory protein models.

Protein model templates for the four chemosensory families onto which residues identified as selection candidates (top 1% Fst) are mapped. The colour coding (bottom right box) indicates the number of times a particular residue was identified as a candidate in pair-wise population comparisons. Although monomeric proteins are shown, IRs and ORs form heteromeric complexes of ligand-tuning receptors with structurally related co-receptors6, and GRs are also likely to function in multimeric assemblies16. Double-headed arrows next to these protein models indicate the approximate position of the sensory neuron membrane. IR: residues are mapped onto the X-ray crystal structure of the AMPA iGluR (PDB 3KG2). The IR amino-terminal region is much shorter and highly divergent from that of iGluRs, leading to very poor alignment quality, so the precise three-dimensional position of the mapped residues in this region is not informative. OR: residues are mapped onto the OR85b model built by amino-acid coevolutionary and secondary structure analyses41. The large dark-grey spheres on the OR structure highlight the location of residues experimentally implicated in influencing ligand recognition properties. We have excluded the high Fst residues for OR22b and OR22c due to the complex nature of the locus (polymorphic chimeric). GR: residues are mapped onto a snake plot of GR10b, as no three-dimensional information is available. OBP: residues are mapped onto the LUSH (OBP76a) structure (PDB: 2GTE). The green sphere indicates the internal cavity where the ligand is expected to reside.

Chemosensory genes carry signatures of selective sweeps

Given the striking evidence for positive selection based on allele frequency differences between D. melanogaster populations, we reasoned that signatures of selective sweeps might also be borne out in the SNP site frequency spectra (SFS). We tested this hypothesis by computing Fay and Wu's H statistic (H) across all multigene families44; an excess of high-frequency-derived alleles is reflected by negative H values and is indicative of a selective sweep. Notably, of the nine families possessing negative H estimates, three of these were chemosensory families (Or, Gr and Obp; Fig. 5a). Coalescent simulations, conditioned on the number of segregating sites observed within individual chemosensory genes and over a range of recombination and demographic parameters, identified a number of outliers in all chemosensory families (Supplementary Data 1 and 3). Similar to our divergence analyses (Fig. 2d), we examined the distribution of H among stage- and function-specific subgroups of chemosensory families. Here the only functional grouping that alone had a significant signature of adaptation was the adult-specific Grs (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5. Analyses of nucleotide diversity.

(a) Rank-ordered distribution of Fay and Wu's H values across large protein families. Horizontal lines indicate 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. Negative values indicate an increase in the abundance of high-frequency-derived mutations, which are signals of selective sweeps. Additional coalescent simulations were carried out to test the significance of individual genes (Supplementary Data 3). (b) Fay and Wu's H values estimated for functional groupings within chemosensory families. Horizontal lines indicate 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. Numbers along the right margin indicate the number of genes included in the analyses, with the asterisk indicating significantly negative H (95% confidence interval excludes 0). (c) Box plots contrasting the ratio of replacement diversity to silent diversity (a population-level measure of functional constraint) among the chemosensory families and the pooled non-chemosensory protein families. Significant heterogeneity exists among PR/PS values (P values<<0.01; Kruskal–Wallis test). The only pair-wise comparisons remaining significant after correcting for multiple tests are the chemosensory versus large family comparisons (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests P values<0.005).

We additionally carried out a genome-wide selection scan using the composite likelihood ratio (CLR) test45. We again observed that chemosensory loci harboured significantly higher CLR values than the other protein families; this suggests that the former harbour a greater proportion of loci that have skews in the SFS, consistent with positive selection (Supplementary Fig. 4). These SFS-based results provide complementary lines of evidence to our Fst findings, further arguing that sensory protein families are experiencing directional selection at higher rates compared to other large protein families. This unique view of protein family population dynamics highlights the primary role that loci involved in chemosensory perception have had in acting as ‘first responders' when adapting to new ecologies as D. melanogaster expanded globally.

Of the proteins that are SFS-based selection candidates, only a few have known ligands, but several of these define sensory pathways linked to specific behavioural phenotypes (Supplementary Data 1). For example, OR47b, OR88a and GR68a are all necessary for the detection of fly-produced chemicals that control different sexual and/or attraction behaviours46,47, OR49a (introduced above) detects a parasitic wasp semiochemical to mediate avoidance10, and GR43a is an internal sensor of fructose involved in feeding regulation48. These and other characterized genes represent excellent candidates for future studies linking adaptive mutations to phenotypic consequences.

Chemosensory families adapt through standing variation

The extent to which adaptive selection acts on standing variation versus de novo mutations is a fundamental and debated topic because of its relevance for understanding rates of adaptation3,49. Having sampled the ancestral-like Zimbabwe population, we were able to address this issue for the D. melanogaster chemosensory system. Examination of the set of alleles inferred to be under positive selection (BayeScan based or 1% Fst tail) indicated that alleles with the derived state regularly segregate in the ancestral range (92%). In addition, most high-frequency-derived mutations within individual genes that carry significantly negative H values are variable within the Zimbabwe lines. These data imply that a classic hard sweep model—in which adaptive alleles originate as de novo mutations and are quickly fixed—is not supported for the chemosensory loci carrying signals of adaptation.

The observation that selection at chemosensory loci appears to occur rapidly, and predominantly on standing variation, prompted us to seek evidence for divergent selection at different protein-altering positions within the same gene. Instances of this phenomenon would potentially illustrate multiple selective events on the same protein (divergent selection), and may indicate that adaptation at these loci is not mutation limited. To address this question, we investigated genes within this same candidate set (BayeScan based or 1% Fst tail) that harboured two or more highly differentiated amino-acid-altering polymorphisms between populations. In total, 12 of these genes showed signals of divergent selection between populations for different amino-acid-changing SNPs: Or22a, Or22b, Or59a, Gr36b, Gr36c, Gr59d, Gr59e, Gr93d, Ir11a, Ir48b, Ir48c and Ir75b. Different populations may therefore have utilized different protein variants from the pool of standing variation to adapt locally.

Rarity of novel chemosensory genes within D. melanogaster

In addition to protein divergence, comparative genomic studies have demonstrated that gene gains and losses are frequent and important events for chemosensory families50,51. The causes for the changes in family sizes remain unresolved, but have occasionally been correlated with ecology and lifestyles18,20,21.

Using our polymorphism data, where signals of selection and mutational processes remain the strongest, we examined the earliest stages of family size change. For comprehensive quantification of the relative frequencies of functional gains (new gene duplicates) versus functional loss (gene-disrupting mutations), we utilized genome-wide SNP, indel and CNV variant calls23,26.

Within our set of 2,221 duplications, complete gene duplications of chemosensory loci are rare (4 Grs (7%); 5 Ors (8%); 0 Irs (0%); 2 Obps (4%)). Moreover, none of these duplications segregate in >16% of the individuals in one population and only one of the duplications (Or43b) segregates in multiple populations (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Data 4). These data indicate that recent functional diversification through whole-gene duplication within D. melanogaster is rare.

We did uncover, however, several instances of novel chemosensory gene structures resulting from CNVs joining nearby genes. In total, we observe 11 chimeric structures and 6 gene fusions involving chemosensory genes (Supplementary Data 4). While chimeric structures were as likely to involve genes on the same or on opposite strands, all six gene fusions were between chemosensory genes on the same strand. Similar to the whole-gene duplications, nearly all these novel structures are found at low frequencies and/or are unlikely to be functional based on intron/exon structures. The two exceptions are fusions of Or22a and Or22b (ref. 52) and a novel fusion of Or65b and Or65c (Supplementary Data 4).

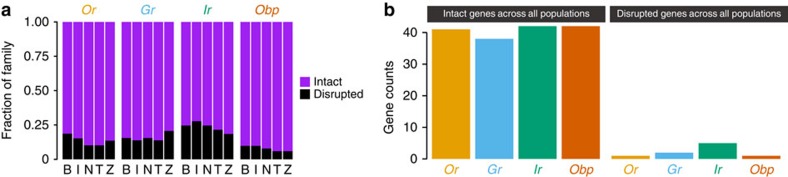

Polymorphic gene loss is common within chemosensory families

In contrast to the paucity of new genes and protein gene structures, we observed a high frequency of disrupted alleles of chemosensory loci. Among the total set of deletions, sensory genes are significantly overrepresented based on gene ontology functional enrichment tests (Supplementary Data 5; Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Contrasting the ratios of deletions to duplications, we estimate values ranging from ∼5:1 (Obps, Grs and Ors) to 19:0 (Irs). In an evolutionary context, if we assume that the deletions in this set that segregate at >10% are effectively neutral, we would expect drift alone to reduce each of these protein families at 4–14 times the rate that they expand (Grs: 14:0; Irs: 7:0; Ors: 6:1; Obps: 4:1). This trend would be consistent with the reduction in the Or, Gr and Ir families that has been inferred using between-species data15,20.

In addition to the CNV data, nonsense mutations within Grs and Irs were roughly twice as frequent compared with other large protein families; a similar trend was not seen for the Ors or Obps (Supplementary Data 6; Supplementary Table 5). We did not observe any enrichment in small frameshifting indels within the chemosensory loci (Supplementary Table 5). To provide an estimate for the fraction of each of the chemosensory families that harbours loss-of-function mutations, we combined these SNPs and small indels with the CNV disruptions. We additionally required at least one of these disruptive mutations to be segregating ≥10% of the individuals in one population (because mutations were collapsed, there are multiple instances of genes harbouring several null mutations). Summarized in this way, all chemosensory families carry appreciable numbers of null alleles; in some cases, these can be quite high (for example, ∼25% for the Irs) (Fig. 6a). While many chemosensory genes remain intact across all populations, there is a small fraction of each gene family that segregates nulls in all populations (Fig. 6b). Notably, there is no trend with respect to the populations. For example, the Zimbabwe sample does not systematically possess the fewest null alleles, which might have been expected if an out-of-Africa bottleneck was principally responsible for the relaxed constraint in the derived populations.

Figure 6. Polymorphic disruptive mutations are common.

Summaries for the counts and fraction of the chemosensory families that have null mutations segregating at frequencies ≥10% in the populations. (a) The fraction of the gene families that harbour null alleles segregating at ≥10% in the populations. B, Beijing; I, Ithaca; N, Netherlands; T, Tasmania, Z, Zimbabwe. (b) Counts of genes that contain either no high-frequency null mutations across the five populations or contain high-frequency mutations in all five populations.

The mutational target size for gene loss is much larger than for gene gain, and the observed excess of polymorphic disruptive mutations compared with new genes is unsurprising. However, the significant enrichment specifically for chemosensory genes suggests that some are likely to be under relatively relaxed purifying selection, potentially allowing weakly deleterious mutations to persist in the population for longer and at higher frequencies. Overall, selective constraint based on the nucleotide diversity at replacement sites scaled by nucleotide diversity at silent sites (PR/PS) indicates that purifying selection is the predominant force acting across all protein families (PR/PS<1 for all gene families; Fig. 5c). However, chemosensory genes do have PR/PS distributions that are slightly elevated compared with the background estimate provided by the large protein data set, consistent with weaker purifying selection (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

The immense molecular and functional diversity of sensory systems between species is increasingly well appreciated. Beyond documenting these differences, however, understanding how such variation emerges within a population, and how it is fixed between species, requires knowledge of the evolutionary forces that govern these changes. Because the genetic signatures required to test models of adaptive evolution are quickly lost22, this aim necessitates population genetic data sets.

We have leveraged a population genomic dataset for geographically diverse samples of D. melanogaster to investigate the role of adaptive evolution in the recent history of this species' chemosensory system. A striking result that emerged is the contrast between the signatures of adaptive evolution between the divergence (interspecific) and polymorphic (intraspecific) timescales. Chemosensory genes are not outliers for adaptive changes between species in the context of other multigene families. However, within D. melanogaster, these genes carry some of the most pronounced signatures of positive selection. Moreover, we have shown that selection has operated predominantly on standing variation, and that there is evidence for multiple advantageous alleles segregating at some loci. In addition, there is strong evidence that the chemosensory protein families are under weaker purifying selection relative to other large protein families, with a higher than expected number of disruptive mutations segregating within them, and elevated PR/PS distributions.

Our detection of signatures of both positive selection and relaxed constraint suggests hypotheses for the modes of evolution experienced by the chemosensory protein families. We propose that chemosensory genes are under weaker purifying selection as a result of: (i) a high level of functional redundancy (overlapping ligand recognition38,53 or chemosensory-evoked behavioural functions), (ii) fluctuating purifying selection over diverse ecological niches (spatially varying selection) and (iii) a relative freedom from pleiotropic constraints (their action on downstream processes is accomplished solely by the activation of specific classes of chemosensory neurons, and loss of function of these genes does not directly cause lethality or extreme phenotypes). The confluence of these attributes creates a class of genes that would be expected to respond rapidly to selective pressures: there would be ample genetic variation segregating at appreciable frequencies, and little genetic correlation with non-selected traits to impede the direction of selection3,54. Our demographically diverse D. melanogaster samples appear to have provided an opportune timeframe to observe this swift adaptive response to new environments.

Over longer time periods, we propose that signatures of adaptation at other loci ‘catch up' with the initial rapid bout of adaptation of chemosensory genes. This could explain why comparative studies spanning longer time periods would tend to average out selective signals. An additional contributing factor might be that the environmental fluctuations within Africa during the D. melanogaster speciation event did not match those that the species endured during its global expansion.

In conclusion, we have shown that the peripheral chemosensory system of D. melanogaster shows strong signatures of selection over short timescales. These results, together with the existing and emerging molecular and neurogenetic tools, provide an exciting foundation for investigating the genetics of adaptation at the functional level.

Methods

Genomic data

The genomic data used for the study originated from the GDLs23, a reference panel consisting of 84 lines derived from five world populations: Beijing–China (15 lines), Ithaca–USA (19 lines), Netherlands (19 lines), Tasmania (18 lines) and Zimbabwe (13 lines)55. These lines were inbred for 12 generations and are mostly homozygous, except for regions associated with inversions, which could not be inbred (referred to as ‘heterozygous blocks'23). GDLs were fully sequenced to an average depth of 12.5 × per line, and independent validation for both SNP and small indels were generated. These high-quality SNP and small indel calls are publicly available (SRA study SRP050151). In this work, we used the SNP calls that remained after applying the IBD and callability masks23. The SNP annotations that were generated by SNPeff56 are the same as in the original GDL publication23. Nonsense mutations used in the analyses of null alleles were based on these annotations. For the null alleles resulting from small indels, we crossed exon BED files for our gene families with the GDL's small indel VCF file. Frameshifting indels that fell within exon sequences were considered disruptive. SNP diversity estimates per site for our gene sets were generated using vcftools57 (v0.1.11). Divergence statistics were based on the available alignment of the GDL SNPs to D. melanogaster (dm3), D. simulans (droSim2), D. sechellia (droSec1), D. erecta (droEre2) and D. yakuba (droYak2); probabilistic ancestral calls exist for all variable sites. Estimations for the total number of nonsynonymous (ns) and synonymous (s) positions within our gene sets were based on the degeneracy of the codons as annotated by SNPeff: lengthns=L1+2/3(L2)+1/3(L3) and lengths=L4+1/3(L2)+2/3(L3), where Lx is the number of x-fold degenerate sites.

CNV data sets

CNVs were identified by integrating the results of three independent CNV detection pipelines: Pindel58 (v2.07.11; split-read detection), an in-house pipeline designed around BLAT59 (split-read detection) and Delly60 (v0.0.7; paired-end detection). The initial set of calls was subjected to several filters and its quality was evaluated by PCR (6–12% false discovery rate depending on whether read depth further supported the call). The final CNV data set consists of 2,221 duplications, 56,562 deletions and 3,850 insertions relative to the reference genome and varying in size between 25 bp and 25 kb (the chosen size limits)26. For the gene structure analyses, we defined ‘chimeric' structures as duplication events that partially duplicate two genes to produce a novel gene structure (the original two loci remain unaltered, leading to family size expansion). We defined ‘gene fusions' as genic structures arising by a deletion event that brought together portions of two tandem genes into a single structure (leading to family size reduction).

Definition of protein families

Protein family groupings were based on the evolutionary and functionally informed classification scheme implemented in the PANTHER database25. To extract the large protein families, we downloaded the total set of ‘Protein Classes' from the database. We removed redundant members from these classes and we retained only those families that had ≥20 members. We then cross-referenced the gene IDs within the PANTHER database entries with gene IDs from FlyBase to ensure correct naming convention. Any PANTHER entry that did not identify a gene within FlyBase was removed. We also excluded the chemosensory protein families and replaced them with our own manually curated set. In total, our ‘large protein family' data set (including chemosensory genes) comprises 40 families, encompassing ∼1,200 genes (Supplementary Data 8).

Polymorphism-divergence tests of selection

Silent and replacement polymorphism was defined by crossing BED files of genes within our large protein family data set with the GDL SNP annotation results23 outputted by SNPeff56. Divergences were counted based on published probabilistic calls23; only positions within the alignments having ≥85% posterior probability were retained. MK based tests28 (using a Fisher's exact test) utilized only the African polymorphism data. To avoid tests on genes with too few divergences or too little polymorphism, we required the marginal counts of the MK tables to be >6. We additionally carried out polarized MK tests with these data using the inferred ancestral state calls described above. DoS calculations30 were made based on the MK tables using an R script. To estimate the fraction of amino-acid substitutions driven to fixation by positive selection (α), and α scaled by the synonymous substation rate (ωa), we used the DoFE package (www.lifesci.susx.ac.uk/home/Adam_Eyre-Walker/Website/Software.html). Divergence, polymorphism, lengthns and lengths counts that were input for DoFE were calculated using the SNPeff annotations as described above. To create equal sample sizes across the African loci for the ωa estimate, we imputed missing data based on the African-specific allele frequencies.

F st analyses

Genome-wide Fst estimates were generated using the approach of Weir and Cockerham61, which allows for unequal sampling between populations. Fst values for each gene within our large protein family data set were extracted by crossing our BED files with the Fst files. Similarly, assigning the positions as silent or replacement was achieved with the SNPeff annotations described above.

For input to BayeScan36 (v2.1), we filtered all polymorphic sites from our large protein family data set that had a minor allele frequency ≤0.15. We converted our data files from VCF to 012 format using vcftools57 (v0.1.12a). We used this resulting 012 file to produce the BayeScan input file using a custom R script. To run BayeScan on each gene family, we modified the default settings so that the ‘-pr_odds' switch was set to 10 and outputted the full trace data.

SFS scan for selection

We applied the method of Nielsen et al.45, implemented in SweeD62 (v3.2.11), to the full folded SNP data set for each of the five populations independently. For each data set, the CLR was calculated over a grid of 60,000 (-grid 60,000), which resulted in estimates over ∼400 bp. To compare CLRs between gene families (Supplementary Fig. 4), we extracted CLR estimates for each gene family based on the coordinates within the BED files (see above).

Coalescent simulations

Coalescent simulations to determine outlier Fst values were carried out using msms63.

The topology of the model was based on the previously computed genome-wide Fst23, but with a forced polytomy between the short terminal branches of the Netherlands, Ithaca and Tasmania populations. We additionally allowed for migration between the African and ancestral out-of-Africa branch (see Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 8 for the simulation parameters).

The coalescent simulations used to investigate the significance of Fay and Wu's H were run using ms64. For each chemosensory family, our simulations were based on the median length of the genes (Ors and Grs=1,500 bp; Irs=2,000 bp; Obps=600 bp). We ran 10,000 simulations for three demographic models (Supplementary Data 8), for three recombination rates (ρ=1, ρ=50, ρ=250), and conditioning on the number of segregating sites within each candidate gene. We calculated summaries of the distribution of Fay and Wu's H using the ‘sample_stats' utility within ms64. Simulation commands are available in Supplementary Data 7.

SNP-based summary statistics

Fay and Wu's H44 was calculated using the ‘stats' utility within the ms distribution64. For input into ‘stats', we treated each gene sample as a haplotype by randomly selecting one of two alleles if a given gene contained heterozygous sites. In addition, missing data were imputed based on the population-specific allele frequency of the site.

Lifetime kurtosis

We obtained lifetime kurtosis (KL) estimates by first merging available olfactory receptor response data sets within the Database of Odorant Responses39 (DoOR). DoOR is an R-based65 database, with accompanying data processing functions, and implements a model-based approach for combining heterogeneous receptor response data sets. We used DoOR's ‘modelRP' function to merge data sets where more than one existed for a given receptor. We then estimated the KL on this merged response data using formula (1):

|

where M is the number odorants tested, ri is the receptor response to the ith odorant,  is the overall mean response for the receptor and σr is the s.d. of responses the given receptor66. To relate KL to Fst estimates, we took the average Fst across all SNPs within a given receptor's gene, and overall 10 pair-wise population comparisons.

is the overall mean response for the receptor and σr is the s.d. of responses the given receptor66. To relate KL to Fst estimates, we took the average Fst across all SNPs within a given receptor's gene, and overall 10 pair-wise population comparisons.

Mapping residues onto protein models

The most extreme amino-acid-changing SNPs (top 1% Fst or BayeScan candidates) in chemosensory proteins were mapped onto three-dimensional protein model ‘templates' by generating protein alignments of each family, including the template sequence, using PROMALS3D67, locating the equivalent position in the template sequence to each of the candidate selection residues, followed by graphical visualization using VMD68. This mapping approach provides a coarse-grained view of the location of candidate selection residues within the proteins, as it is limited by the quality of the alignment of these divergent protein families, and the quality and accuracy of the template structure. For IRs, we aligned all D. melanogaster IRs, as well as D. melanogaster and selected mammalian iGluRs, and used the X-ray crystal structure of the AMPA family iGluR GluA2 (PDB 3KG2) as a template69. For ORs, we used an alignment of D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. erecta and D. yakuba ORs20 with the evolutionary coupling-based model of OR85b (version 140_12) as template41. For GRs, we used an alignment of D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. erecta and D. yakuba GRs20; because neither three-dimensional structure nor models exist, candidate residues were mapped onto a snake plot representation using GR10b as template. For the OBPs, we aligned all drosophilid OBPs70 (excluding Obp84a, Obp56c, Obp59b, Obp59a, Obp83ef and Obp83c because of their unusual length), and used the X-ray crystal structure of LUSH as the template (PDB: 2GT3)43 within PROMALS3D67.

PCR sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted by crushing single flies in 50 μl of DNA extraction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaCl, 200 μg ml−1 Proteinase K), incubating for 30 min at 37 °C, before inactivation of Proteinase K with a 5-min incubation at 95 °C. Primers sequences are available in Supplementary Table 6. PCR amplification followed standard protocols followed by Sanger sequencing of the PCR amplicon.

Data availability

The sequence and annotation data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in NCBI's Sequence Read Archive, with the project identifier SRP050151 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/sra.cgi?study=SRP050151) (refs 23, 26).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Arguello, J. R. et al. Extensive local adaptation within the chemosensory system following Drosophila melanogaster's global expansion. Nat. Commun. 7:11855 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11855 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1 - 5, Supplementary Tables 1 - 6 and Supplementary References

Summary of selection candidates and functional data. The tables list all protein members within the four main chemosensory families, a subset of functional data ascribed to them, and the selection tests that have identified them as "selection candidates". For the MK-test columns we have separated the tests for which all substitutions between D. melanogaster and its last common ancestor have been included (non-polarized), or for only the substitutions along the D. melanogaster branch (polarized). We list all genes that have an MK-test p<0.05 with "*" indicating those loci that remain significant after Bonferroni correction. For the two Fst approaches ("1% Fst Candidate" and "BayeScan Candidate") we have listed only those genes that contain protein-altering SNPs identified as outliers. For the genes listed in the "Fay and Wu's H Candidate" column, we required that a given gene remain significant (p<0.05) across all three of the demographic settings we simulated under, and for at least the two higher recombination rates that examined (ρ = 50 and 250; Supplementary Table 4). Due to the heterogeneity in the methods used to measure tissue expression, we have simplified the classification for this table. In addition to the individual cases cited within the manuscript, we also acquired functional information from published resources.

Fst results based on coalescent simulations under three demographic models. The table provides the empirical 1% threshold for genome-wide Fst values over all 10 pair-wise population comparisons as well as the 1% and 5% thresholds resulting from the coalescent simulations under three demographic scenarios. The right-most columns indicate whether the empirical thresholds superseded those observed in the simulations.

Coalescent simulations results for Fay and Wu's H under three demographic models and three recombination parameters. The tables provide lists of genes from each of the main chemosensory families inferred to have a negative Fay and Wu's H value. Coalescent simulations were carried out using three recombination parameters (Rho), and conditioning on the number of segregating sites observed for each gene, with a gene length set to the median gene length for the family (Methods). The right most columns indicate if a given gene's H value is significant ("**" indicates significance at the 2.5% level; "*" indicates significance at the 5% level) for the three demographic models examined (Supplementary Fig. 5; Methods). Blank cells indicate that the H value was not found to be significant under the given parameters.

Chemosensory CNVs. Detailed information for the chemosensory gene CNVs. Sheet 1 provides the set of coordinates for all CNVs described in the paper (columns A-H), their annotation status details (I-P), their overall frequencies in the total dataset (Q), their presence or absence (1 or 0, respectively) for the CNV within each of the 84 lines (R-DB), whether coverage was used for calling their presence (DC), and their pair-wise population Fst values. Sheets 2-4 are subsets of sheet 1, to easily access information on the novel gene structures found with the data (gene duplications, chimeric gene structures, and gene fusions).

Population-level summary of duplication and deletion mutations with the chemosensory families. The tables list all members for the four main chemosensory families, color-coded to indicate the presence and frequencies of deletion mutations (color key is in the upper right corner of table). A figure within a cell indicates the number of independent deletions. Bold face gene names indicate that the locus also contains a duplication. The column titled "Shared Between Populations" indicates whether the mutations are also found in other populations. Population abbreviations: B=Beijing; I=Ithaca; N=Netherlands; T=Tasmania; Z=Zimbabwe.

Population-level summary of SNP-based and small indel protein disruptive mutations. The tables list all members for the four main chemosensory families. Color is used to indicate the presence of disruptive mutations given either no frequency cut-off (left tables), or conditional on a 10% frequency cut-off (right tables; color key is in upper right corner of the table). Both SNP and indel mutations are included in the tables, thus some genes harbor more than one class of disruptive mutation. The frequency cut-off was based only on a single class of mutation (we did not sum mutations for the frequency cut-off). Abbreviations for the populations: B=Beijing; I=Ithaca; N=Netherlands; T=Tasmania; Z=Zimbabwe.

Commands for Fst and Fay and Wu's H simulations.

Bed files for the protein families used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Benoîte Bargeton for her assistance with the protein model analyses, and Thomas Auer, Tim Connallon, Angela M. Early, Greg Ewing, Jeff D. Jensen, Stefan Laurent, Jaaved Mohammed, and Benjamin Prud'homme and members of the Benton laboratory for discussion and/or comments on the manuscript. The computational work was performed at the Vital-IT (http://www.vital-it.ch) Center for high-performance computing of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. J.R.A. was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from Novartis Foundation for medical-biological Research (12A14). Research in R.B.'s laboratory is supported by the University of Lausanne, an ERC Consolidator grant (615094), an HFSP Young Investigator Award (RGY0073/2011) and the SNSF Nano-Tera Envirobot project (20NA21_143082).

Footnotes

Author contributions J.R.A. conceived the project; J.R.A. and M.C.M. designed and carried out the analyses with input from A.G.C. and R.B.; J.R.A., M.C.M., J.K.G., S.G. and A.G.C. generated the genomic data; J.R.A. and R.B. wrote the paper with input from all co-authors.

References

- Hereford J. A quantitative survey of local adaptation and fitness trade-offs. Am. Nat. 173, 579–588 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A. The genomic rate of adaptive evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 569–575 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett R. D. H. & Schluter D. Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 38–44 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. A. Theories of adaptation: what they do and don't say. Genetica 123, 3–13 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosshall L. B. & Stocker R. F. Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 505–533 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuin L. et al. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron 69, 44–60 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J. Y., Dahanukar A., Weiss L. A. & Carlson J. R. Molecular and cellular organization of the taste system in the Drosophila larva. J. Neurosci. 31, 15300–15309 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh T.-W. et al. The Drosophila IR20a clade of ionotropic receptors are candidate taste and pheromone receptors. Neuron 83, 850–865 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensmyr M. et al. A conserved dedicated olfactory circuit for detecting harmful microbes in Drosophila. Cell 151, 1345–1357 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim S. A. M. et al. Drosophila avoids parasitoids by sensing their semiochemicals via a dedicated olfactory circuit. PLoS Biol. 13, e1002318 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer T.O. & Benton R. Sexual circuitry in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 38, 18–26 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast J. D. et al. Evolved differences in larval social behavior mediated by novel pheromones. eLife 3, e04205 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton R., Vannice K. S., Gomez-Diaz C. & Vosshall L. B. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell 136, 149–162 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytz R., Croset V. & Benton R. Ionotropic receptors (IRs): chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors in Drosophila and beyond. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 888–897 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croset V. et al. Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLOS Genet. 6, e1001064 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman E. G. & Dahanukar A. Molecular neurobiology of Drosophila taste. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 34, 140–148 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal W. S. Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 373–391 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H. & Wanner K. The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family. Genome Res. 16, 1395 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp A. et al. Evolution of gene expression in the Drosophila olfactory system. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1081–1092 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride C. S. & Arguello J. Roman. Five Drosophila genomes reveal nonneutral evolution and the signature of host specialization in the chemoreceptor superfamily. Genetics 177, 1395–1416 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad Y., Wiebe V., Przeworski M., Lancet D. & Pääbo S. Loss of olfactory receptor genes coincides with the acquisition of full trichromatic vision in primates. PLoS Biol. 2, E5 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski M. The signature of positive selection at randomly chosen loci. Genetics 160, 1179–1189 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier J. K. et al. Global diversity lines—a five-continent reference panel of sequenced Drosophila melanogaster strains. G3 (Bethesda) 5, 593–603 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan W. & Li H. The recent demographic and adaptive history of Drosophila melanogaster. Heredity 98, 65–68 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H., Muruganujan A. & Thomas P. D. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D377–D386 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Moreira M. et al. Evidence for the fixation of gene duplications by positive selection in Drosophila. Genome Res. 10.1101/gr.199323.115 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliman R. M. et al. The population genetics of the origin and divergence of the Drosophila simulans complex species. Genetics 156, 1913–1931 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. H. & Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature 351, 652–654 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierne N. & Eyre-Walker A. The genomic rate of adaptive amino acid substitution in drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1350–1360 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoletzki N. & Eyre-Walker A. Estimation of the neutrality index. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 63–70 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossmann T. I., Keightley P. D. & Eyre-Walker A. The effect of variation in the effective population size on the rate of adaptive molecular evolution in eukaryotes. Genome Biol. Evol. 4, 658–667 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceição I. C. & Aguadé M. Odorant receptor (or) genes: polymorphism and divergence in the D. melanogaster and D. pseudoobscura lineages. PLoS One 5, e13389 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W. D., Cayirlioglu P., Kadow I. G. & Vosshall L. B. Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila. Nature 445, 86–90 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sella G., Petrov D. A., Przeworski M. & Andolfatto P. Pervasive natural selection in the Drosophila genome? PLoS Genet. 5, e1000495 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermehren-Schmaedick A., Scudder C., Timmermans W. & Morton D. Drosophila gustatory preference behaviors require the atypical soluble guanylyl cyclases. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol. 197, 717–727 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foll M. & Gaggiotti O. A genome-scan method to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a Bayesian perspective. Genetics 180, 977–993 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallem E. & Carlson J. Coding of odors by a receptor repertoire. Cell 125, 143–160 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbering A. F. et al. Complementary function and integrated wiring of the evolutionarily distinct Drosophila olfactory subsystems. J. Neurosci. 31, 13357–13375 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galizia C. G., Münch D., Strauch M., Nissler A. & Ma S. Integrating heterogeneous odor response data into a common response model: A door to the complete olfactome. Chem. Senses 35, 551–563 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbering A. F. & Benton R. Ionotropic and metabotropic mechanisms in chemoreception: ‘chance or design'? EMBO Rep. 11, 173–179 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf T. A. et al. Amino acid coevolution reveals three-dimensional structure and functional domains of insect odorant receptors. Nat. Commun. 6, 6077 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T., Pellegrino M., Sato K., Vosshall L. B. & Touhara K. Amino acid residues contributing to function of the heteromeric insect olfactory receptor complex. PLoS One 7, e32372 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse S. W., Zhao R., Smith D. P. & Jones D. N. M. Structure of a specific alcohol binding site defined by the odorant binding protein LUSH from Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 10, 694–700 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay J. C. & Wu C.-I. Hitchhiking under positive darwinian selection. Genetics 155, 1405–1413 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R. et al. Genomic scans for selective sweeps using SNP data. Genome Res. 15, 1566–1575 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar S. et al. The neuropeptide tachykinin is essential for pheromone detection in a gustatory neural circuit. eLife 4, e06914 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweck H. K. M. et al. Pheromones mediating copulation and attraction in drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E2829–E2835 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman E. G., Wisotsky Z. & Dahanukar A. Detection of sweet tastants by a conserved group of insect gustatory receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 1598–1603 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. D. On the unfounded enthusiasm for soft selective sweeps. Nat. Commun. 5, 5281 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smadja C., Shi P., Butlin R. K. & Robertson H. M. Large gene family expansions and adaptive evolution for odorant and gustatory receptors in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 2073–2086 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. M. et al. Extensive copy-number variation of the human olfactory receptor gene family. The American Journal of Human Genetics 83, 228–242 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguadé M. Nucleotide and copy-number polymorphism at the odorant receptor genes Or22a and Or22b in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 61–70 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallem E. A., Dahanukar A. & Carlson J. R. Insect odor and taste receptors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51, 113–135 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S. P. Two steps forward, one step back: the pleiotropic effects of favoured alleles. Proc. Biol. Sci. 271, 705–714 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg A. J., Hackett S. R., Harshman L. G. & Clark A. G. A hierarchical bayesian model for a novel sparse partial diallel crossing design. Genetics 185, 361–373 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, snpeff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Fly 6, 80–92 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P. et al. The variant call format and vcftools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K., Schulz M. H., Long Q., Apweiler R. & Ning Z. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 25, 2865–2871 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Moreira M., Arguello J. & Clark A. Mutation spectrum of Drosophila CNVs revealed by breakpoint sequencing. Genome Biol. 13, R119 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch T. et al. Delly: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics 28, i333–i339 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir B. S. & Cockerham C. C. Estimating f-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38, 1358–1370 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis P., Živkovic D., Stamatakis A. & Alachiotis N. Sweed: likelihood-based detection of selective sweeps in thousands of genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2224–2234 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing G. & Hermisson J. Msms: a coalescent simulation program including recombination, demographic structure and selection at a single locus. Bioinformatics 26, 2064–2065 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics 18, 337–338 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R. Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at www.R-project.org/ (2015).

- Willmore B. & Tolhurst D. J. Characterizing the sparseness of neural codes. Network 12, 255–270 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J., Kim B.-H. & Grishin N. V. Promals3d: a tool for multiple sequence and structure alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2295–2300 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W., Dalke A. & Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolevsky A. I., Rosconi M. P. & Gouaux E. X-ray structure, symmetry and mechanism of an AMPA-subtype glutamate receptor. Nature 462, 745–756 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosophila 12 Genomes Consortium. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature 450, 203–218 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1 - 5, Supplementary Tables 1 - 6 and Supplementary References

Summary of selection candidates and functional data. The tables list all protein members within the four main chemosensory families, a subset of functional data ascribed to them, and the selection tests that have identified them as "selection candidates". For the MK-test columns we have separated the tests for which all substitutions between D. melanogaster and its last common ancestor have been included (non-polarized), or for only the substitutions along the D. melanogaster branch (polarized). We list all genes that have an MK-test p<0.05 with "*" indicating those loci that remain significant after Bonferroni correction. For the two Fst approaches ("1% Fst Candidate" and "BayeScan Candidate") we have listed only those genes that contain protein-altering SNPs identified as outliers. For the genes listed in the "Fay and Wu's H Candidate" column, we required that a given gene remain significant (p<0.05) across all three of the demographic settings we simulated under, and for at least the two higher recombination rates that examined (ρ = 50 and 250; Supplementary Table 4). Due to the heterogeneity in the methods used to measure tissue expression, we have simplified the classification for this table. In addition to the individual cases cited within the manuscript, we also acquired functional information from published resources.

Fst results based on coalescent simulations under three demographic models. The table provides the empirical 1% threshold for genome-wide Fst values over all 10 pair-wise population comparisons as well as the 1% and 5% thresholds resulting from the coalescent simulations under three demographic scenarios. The right-most columns indicate whether the empirical thresholds superseded those observed in the simulations.

Coalescent simulations results for Fay and Wu's H under three demographic models and three recombination parameters. The tables provide lists of genes from each of the main chemosensory families inferred to have a negative Fay and Wu's H value. Coalescent simulations were carried out using three recombination parameters (Rho), and conditioning on the number of segregating sites observed for each gene, with a gene length set to the median gene length for the family (Methods). The right most columns indicate if a given gene's H value is significant ("**" indicates significance at the 2.5% level; "*" indicates significance at the 5% level) for the three demographic models examined (Supplementary Fig. 5; Methods). Blank cells indicate that the H value was not found to be significant under the given parameters.

Chemosensory CNVs. Detailed information for the chemosensory gene CNVs. Sheet 1 provides the set of coordinates for all CNVs described in the paper (columns A-H), their annotation status details (I-P), their overall frequencies in the total dataset (Q), their presence or absence (1 or 0, respectively) for the CNV within each of the 84 lines (R-DB), whether coverage was used for calling their presence (DC), and their pair-wise population Fst values. Sheets 2-4 are subsets of sheet 1, to easily access information on the novel gene structures found with the data (gene duplications, chimeric gene structures, and gene fusions).

Population-level summary of duplication and deletion mutations with the chemosensory families. The tables list all members for the four main chemosensory families, color-coded to indicate the presence and frequencies of deletion mutations (color key is in the upper right corner of table). A figure within a cell indicates the number of independent deletions. Bold face gene names indicate that the locus also contains a duplication. The column titled "Shared Between Populations" indicates whether the mutations are also found in other populations. Population abbreviations: B=Beijing; I=Ithaca; N=Netherlands; T=Tasmania; Z=Zimbabwe.

Population-level summary of SNP-based and small indel protein disruptive mutations. The tables list all members for the four main chemosensory families. Color is used to indicate the presence of disruptive mutations given either no frequency cut-off (left tables), or conditional on a 10% frequency cut-off (right tables; color key is in upper right corner of the table). Both SNP and indel mutations are included in the tables, thus some genes harbor more than one class of disruptive mutation. The frequency cut-off was based only on a single class of mutation (we did not sum mutations for the frequency cut-off). Abbreviations for the populations: B=Beijing; I=Ithaca; N=Netherlands; T=Tasmania; Z=Zimbabwe.

Commands for Fst and Fay and Wu's H simulations.

Bed files for the protein families used in this study.

Data Availability Statement