Summary

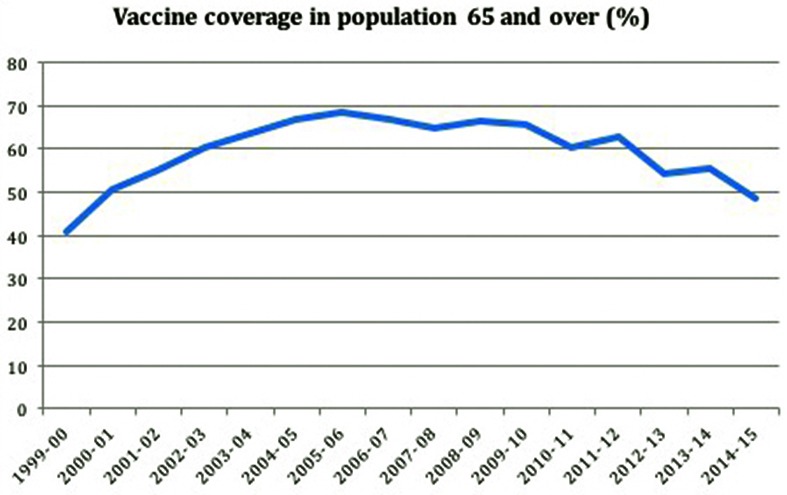

Influenza constitutes an annually recurring threat to society, from both the clinical and economic points of view. The impact of influenza is often underestimated, especially among frail elderly people, who are at increased risk of serious complications, including hospitalization and death. In Italy, around 10 million individuals aged 65 years and older are at risk of contracting influenza, and it can be estimated that the lack of a vaccination strategy would lead to more than 2 million cases and about 30,000 deaths. However, adherence to routinely recommended adult immunizations remains suboptimal despite the availability of safe and effective vaccines. Indeed, a monitoring program from the National Institute of Health in Italy has shown that influenza vaccination coverage in the elderly dropped to 49% in the 2014-2015 season, which is far below the maximum values (68%) recorded in the 2005-2006 season. The current situation in Italy imposes a need for greater sustainability in order to face the challenges related to the changing epidemiological situation, demographic transition and social transformations. Our review sums up the key elements of influenza vaccine sustainability and makes suggestions for improving the organizational structure of the present initiatives.

Key words: Influenza, Vaccine sustainability, Elderly

Introduction

Influenza is considered a highly contagious respiratory illness, mainly because unstable viruses periodically drift and shift their antigens from one season to another to evade the immune system.

Annual winter outbreaks of influenza are a major cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among frail elderly people, who are at increased risk of serious complications, including hospitalization and death [1].

Although the public perception in many countries is that seasonal influenza is a mild illness, with a low to negligible impact on health and economies, annual influenza attack rates range from 5-10% in adults to 20-30% in children, generating high healthcare costs and placing a significant clinical and economic burden on patients and society [2].

Worldwide, these annual epidemics are estimated to result in about 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness, and about 250,000 to 500,000 deaths [3]. From 1976 to 2007, individuals aged ≥ 65 years accounted for approximately 90% of all influenza-related deaths in the USA. Furthermore, during the period 1999-2010, it was estimated in the UK that 2.5-8.1% of deaths among those aged ≥ 75 years were due to influenza [4].

Founded in 1999, Influnet is an Italian network of sentinel physicians, it aims to monitor seasonal trends in influenza-like syndromes (influenza-like illness, ILI) in the population. According to the estimates made from the data gathered, ILI affects 4-12% of the population each year, with an average of 7.5% recorded in the period 2011-2014 [5].

The clinical impact of seasonal influenza epidemics in Europe has recently been extrapolated from American data. According to these estimates, in Italy about 6,000 deaths and 38,000 excess hospitalizations are attributable to influenza [6].

The economic impact of influenza primarily involves healthcare resource utilization by elderly and high-risk groups and work absenteeism among otherwise healthy working adults [7]. In 2013, the costs attributable to the four main adult Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (VPD) in the United States were estimated to be around $ 26 billion, with influenza accounting for the majority of cases of adult VPD (81% of adults aged 50 and older and 77% of adults aged 65 and older). Moreover, the highest annual costs (medical and indirect costs) were indeed related to influenza. Influenza accounted for $ 16,0 billion (60%) of the cost among adults older than 50 years and $ 8,3 billion (54%) among those aged 65 and older [8].

From the patient perspective, an average episode of ILI and clinically diagnosed influenza in the out-of-hospital Belgian general population costs € 51-53 in direct medical costs, 4 days of absence from work or school and the loss of 0.005 quality-adjusted life-years [9]. In Italy, the average length of absence from work or school is around 4.8 days, and 10% of all work absences are due to influenza. The total cost of each case of influenza is estimated to be about € 330 [10], with indirect costs accounting for a further € 364-774 (values from 2011) [11].

Considering that in Italy there are nearly 10 million individuals aged 65 years and older who are at risk of contracting influenza, it can be estimated that the lack of a vaccination strategy would lead to more than 2 million cases and about 30,000 deaths. Indeed, vaccination has the potential to reduce the number of cases to 1,3- 1,5 million. Hence, the reduction in the number of hospital admissions would eventually lead to a reduction in healthcare costs of up to € 80 million (specifically, after administration of vaccines containing adjuvants) [10]. In this regard, one Italian study analyzed data gathered from the cohort of elderly individuals in the Liguria Region; the authors estimated that the costs resulting from hospitalization due to influenza were 5 times higher among non-vaccinated subjects than vaccinated subjects [12].

Moreover, vaccination targeting people from 50 to 64 years old in Italy has the potential to avoid about 100,000 cases of ILI (about 10% of the total), 3,000 hospitalizations (60%), 232 deaths (out of a total of 989) and more than 110,000 days of lost work [6].

European and national strategies and sustainability of influenza vaccination

Bearing in mind the clinical, economic and social impacts of influenza, the World Health Organization has proposed vaccination as a cost-effective and a cost-beneficial tool for preventing serious forms and complications of influenza, and reducing premature mortality in groups at increased risk of serious illness.

In Italy, the 2012-2014 National Immunization Prevention Plan introduced influenza vaccination for the elderly (65 years and over), with coverage targets of 75% (minimum achievable goal) and 95% (optimal goal in the target population). The objective was to reduce individual risk of illness, hospitalization and death, and the related social costs. In addition, several countries have lowered the age threshold to 60 or 50 years for free-of-charge influenza vaccination. These decisions were based on pharmacoeconomic evaluations, which proved that this age-based approach was sustainable, cost-effective and also cost-saving, owing to the increased probability of adherence to vaccination by the population. This approach, together with the analysis published in 2012 by the Italian Society of Hygiene (SItI) [13], prompted the Italian Ministry of Health to launch a thorough discussion among all stakeholders, in order to assess the possibility of progressively reducing the age threshold in the upcoming national anti-influenza recommendations.

Although infectious diseases in older adults have a huge burden, adherence to routinely recommended adult immunizations across Europe remains suboptimal, despite the availability of safe and effective vaccines [1]. Still, vaccination is considered the most efficacious public health tool currently available to protect elderly individuals against influenza [4].

European data indicate that vaccination coverage in groups at risk (patients with concomitant disease) is around 35% [10]. In Italy, monitoring carried out by the National Institute of Health has shown a progressive decline in coverage from the maximum value (68%) recorded in the 2005-2006 season. The lowest levels, reached in the 2014-2015 influenza season, indicated that national coverage had dropped to 49%, another 5 percentage points below the previous season (Fig. 1). This decline in coverage is affecting all Italian regions, with reductions ranging from a minimum value in Lombardy (-3.3%) to a maximum value in Abruzzo (-28.0%), and is depressing Italian coverage rates to the levels estimated fifteen years ago. This situation is making it increasingly difficult for Italy to achieve the European target coverage [14] and must surely prompt profound reflection. Indeed, it is essential to implement measures aimed at turning this situation around; a prerequisite to achieving this is understanding why vaccination, which has been unquestionably successful, is shunned by so many people.

Fig. 1.

Influenza vaccination: vaccination coverage in the elderly (age > = 65 years) (per 100 inhabitants) Seasons 1999-2000/2014- 2015 (Source: Ministry of Health – ISS, based on the summaries submitted by the Regions and Autonomous Provinces of Italy).

While disaffection with vaccination can be partly attributed to the growing number of anti-vaccination campaigns, it stems in large part from the difficulties that the National Health System has in allocating the human/financial resources needed to carry out effective information campaigns directed towards citizens and healthcare workers. The problem of resource allocation is common to many prevention activities that involve immediate costs but yield medium/long-term results. Moreover, these results are often hardly visible, as the success of such initiatives lies in the non-occurrence of a negative event, and therefore a "non-event". This presumably explains why the funding of prevention programs in Italy has traditionally been even lower than the already limited 5% established in the planning documents.

While the European Union has more than doubled its funds for immunization worldwide, from € 10 million to € 25 million for the period 2014-2020, Italy is experiencing a decrease in expenditure on vaccines and a series of difficulties in approving a new national preventive vaccination plan [10]. Indeed, last year's data from OSMED (National Observatory on Drug Use) indicated a 21.2% reduction in spending on influenza vaccines: around € 39 million in total [15, 16]. At the same time, however, around 41.0% of subjects diagnosed with a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract (influenza, cold, acute laryngotracheitis) received an inappropriate antibiotic prescription. This exemplifies how the initial failure to pay for vaccine administration later impacts on patients in terms of increased disease risk and treatment costs.

Bearing in mind the need for the widespread administration of influenza vaccine and the complexities of its distribution, it is obvious just how crucial it is to have a comprehensive communication plan and well-designed infrastructure in order to ensure a maximally effective system of influenza prevention [17]. A clear influenza vaccination policy is essential and the lack of one is a key obstacle to influenza programs. Each country currently handles its own vaccination program/policy, and the lack of international coordination results in the wide variability of vaccine supplies and population targets, thereby potentially exacerbating inequalities at the international and national levels. Furthermore, discrepancies in several choices may be difficult for citizens to understand and could facilitate the activities of the antivaccination movements.

Communication supports the development and implementation of these policies and transforms them into a language that will resonate with policy-makers, partners and the public. A recent study on vaccine programs for European citizens aged 60 years and older showed that, in addition to improved access to vaccines, communication and the awareness of vaccine-preventable diseases, as promoted through an efficient system of reminders, recalls and information, are the main parameters leading to success in establishing a vaccine program [18]. Strategies targeted at increasing positive attitudes, such as health education by means of educational videos, may enhance vaccine acceptance and improve knowledge and attitudes in the elderly [19].

Strengthening the communication capacities of the various contributors to influenza programs should ensure that all stakeholders, especially the public and the media, have access to available resources, tools and scientific expertise. Also, promoting communication between scientists and practitioners should create a suitable environment for transparent information sharing with all the stakeholders. Moreover, communication needs to be adapted to the various local and cultural situations (language, content of information, and means of communication). Not only should communication be go beyond pure messaging and providing information; monitoring and evaluation of the communication process is also critical. Various tools could be used for these purposes, such as social network analysis, surveys, interviews etc., and the results should be used to adjust decision-making processes at the political, programmatic and technical levels.

Reaching out to the subjects that need to be involved is generally not enough to gain public support for prevention programs. The training of health workers, who ought to be motivated and committed to the individual and collective interests of vaccinations, is essential. Indeed, non-adherence to vaccination often stems more from the lack of motivation of educational trainers than from opposition on the part of families. The key role of healthcare workers in promoting access to and awareness and acceptance of, influenza vaccination should not be taken for granted, and strengthening the role of healthcare providers is of the highest importance. At the same time, it is very important that people living with or caring for aging adults get vaccinated. Healthcare personnel are in regular contact with at-risk populations, and strategies for improving vaccination rates among health employees are absolutely essential [20].

Vaccine services should have an efficient organizational structure in order to satisfy the needs of the population and ensure the success of vaccination programs. In this regard, the evaluation of vaccination coverage enables identification of the areas where infectious diseases may occur more easily. Therefore, the influenza vaccination coverage is a key indicator for assessing the effectiveness of vaccine supply, especially in such target population groups as the elderly.

Implementing a computerized system of vaccine registries (computerized immunization registries) connected with municipal registry offices should be seen as a prerequisite to increasing the quality of immunization services, and should be integrated with other existing databases, such as those of sentinel sites, population-based studies, hospitals and out-patient clinics and regional authorities. Indeed, the absence of an accurate surveillance system is considered one of the main obstacles to establishing evidence-based policies to reduce the impact of influenza nationally.

Conclusions

Influenza constitutes a serious health threat, especially for vulnerable populations such as older adults. The importance of promoting healthy aging and increasing vaccination coverage, by sustaining a life-course immunisation approach to limit the burden of the disease, is evident. The current economic and socio-political climate, which is characterized by scant resources and cost-cutting, imposes on our healthcare system the need for a new model of sustainability – one which would be able to face the new challenges related to the changing epidemiological situation, demographic transition and great social transformations. In this regard, financial difficulties could be seen as an opportunity to enhance vaccine prevention as part of a system that makes good health investments that impact positively on direct and indirect healthcare costs.

In addition, not only should the costs of a vaccination campaign be programmed; they could also be notably lower than the unpredictable costs of the disease that is to be avoided, thus confirming that investment in prevention promotes the efficient use of human and financial resources.

The need to support public health and to stress the social and economic value of vaccination is now greater than ever. Communication and the awareness of vaccine-preventable diseases in the general community is an important starting point, and all healthcare professionals and public health/social workers can play a key role in this regard.

Acknowledgments

No funding declared for this overview.

References

- 1.Michel J. Updated vaccine guidelines for aging and aged citizens of Europe. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9:7–10. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peasah SK, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Breese J, Meltzer MI, Widdowson MA. Influenza cost and cost-effectiveness studies globally- a review. Vaccine. 2013;31:5339–5348. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Influenza (Seasonal), 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/ [Accessed 15/01/2016]

- 4. World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological record. Report No.:47;2012 Nov. Available at: http://www.who.int/wer [Accessed 15/01/2016].

- 5.Manso M, Rota M.C, Declich S, Giannitelli S, Nacca G, Rizzo C. Bella A per il Gruppo di lavoro INFLUNET. Rapporto sulla stagione influenzale 2013-2014, INFLUNET: sistema di sorveglianza sentinella delle sindromi influenzali in Italia, 2015. Report number: 15/48. Available at: http://www.iss.it/binary/ publ/cont/15_48_web.pdf. [Accessed 15/01/2016] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gasparini R, Amicizia D, Lai PL, Panatto D. Clinical and socioeconomic impact of seasonal and pandemic influenza in adults and the elderly . Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:21–28. doi: 10.4161/hv.8.1.17622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Postma MJ, Baltussen RP, Palache AM, Wilschut JC. Further evidence for favorable cost-effectiveness of elderly influenza vaccination. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2006;6:215–227. doi: 10.1586/14737167.6.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin JM, McGinnis JJ, Tan L, Mercatante A, Fortuna J. Estimated human and economic burden of four major adult vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States, 2013. J Prim Prev. 2015;36:259–273. doi: 10.1007/s10935-015-0394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bilcke J, Coenen S, Beutels P. Influenza-like-illness and clinically diagnosed flu: disease burden, costs and quality of life for patients seeking ambulatory care or no professional care at all. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102634–e102634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avolio M, Pietro ML, Marino M, Sabetta T, Solipaca A. Prevenzione come garanzia di sostenibilità e sviluppo del Servizio Sanitario Nazionale. I Report – Prevenzione Vaccinale. Roma. Istituto di Sanità Pubblica-Sezione Igiene, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 2015. Available at: http://www.avis.it/userfiles/file/News/giugno 2015/Report Prevenzione Vaccinale.pdf. [Accessed 15/01/2016].

- 11.Colombo GL, Ferro A, Vinci M, Zordan M, Serra G. Cost-benefit analysis of influenza vaccination in a public healthcare unit. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2006;2:219–226. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.2006.2.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasparini R, Lucioni C, Lai P, Maggioni P, Sticchi L, Durando P, Morelli P, Comino I, Calderisi S, Crovari P. Cost-benefit evaluation of influenza vaccination in the elderly in the Italian region of Liguria. Vaccine. 2002;20(Suppl 5):B50–B54. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonanni P, Gasparini R, Greco D, Mennini FS, Rossi A, Signorelli C. Abbassamento dell'età di raccomandazione della vaccinazione anti-influenzale a 60 anni: una scelta per la salute e per l'economia del Paese. Societa Italiana di Igiene (SITI). Available at: http://www.societaitalianaigiene.org/site/new/images/docs/gdl/vaccini/201360enni.pdf [Accessed 15/01/2016]

- 14. Direzione Generale della Prevenzione. Coperture vaccinali. Ministero della Salute. Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_tavole_19_allegati_iitemAllegati_0_fileAllegati_itemFile_3_file.pdf [Accessed 16/01/2016]

- 15. Osservatorio Nazionale sull'Impiego dei Medicinali, Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. L'uso dei farmaci in Italia. Rapporto Nazionale, Roma 2015 Jan-Sept. Available at: http://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/sites/default/files/Rapporto_OsMed_gennaio_settembre_2015.pdf [Accessed 16/01/2016]

- 16. Osservatorio Nazionale sull'Impiego dei Medicinali, Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. L'uso dei farmaci in Italia. Rapporto Nazionale 2014, Roma 2015. Available at: http://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/sites/default/files/Rapporto_OsMed_2014_0.pdf [Accessed 16/01/2016]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enhancing Communication around Influenza Vaccination. Workshop. Atlanta (USA), 2013 June. Available at: http://www.who.int/influenza_vaccines_plan/resources/Summary_report_communication_workshop_GAP_2013.pdf [Accessed 17/01/2016]

- 18.Michel JP, Chidiac C, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Johnson RW, Lambert PH, Maggi S, Moulias R, Nicholson K, Werner H. Coalition of advocates to vaccinate of Western European citizens aged 60 years and older. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21:254–257. doi: 10.1007/BF03324911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Worasathit R, Wattana W, Okanurak K, Songthap A, Dhitavat J, Pitisuttithum P. Health education and factors influencing acceptance of and willingness to pay for influenza vaccination among older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:136–136. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0137-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Influenza Vaccination of Health Care Personnel. National action plan to prevent health care-associated infections: road map to elimination. Dept. of Health & Human Services (US), 2013 Apr. Available at: http://health.gov/hcq/pdfs/hai-action-planhcp-flu.PDF [Accessed 18/01/2016].