Abstract

Introduction:

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s Multi-sectoral Partnerships Initiative, administered by the Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention (CCDP), brings together diverse partners to design, implement and advance innovative approaches for improving population health. This article describes the development and initial priorities of an action research project (a learning and improvement strategy) that aims to facilitate continuous improvement of the CCDP’s partnership initiative and contribute to the evidence on multi-sectoral partnerships.

Methods:

The learning and improvement strategy for the CCDP’s multi-sectoral partnership initiative was informed by (1) consultations with CCDP staff and senior management, and (2) a review of conceptual frameworks to do with multi-sectoral partnerships. Consultations explored the development of the multi-sectoral initiative, barriers and facilitators to success, and markers of effectiveness. Published and grey literature was reviewed using a systematic search strategy with findings synthesized using a narrative approach.

Results:

Consultations and the review highlighted the importance of understanding partnership impacts, developing a shared vision, implementing a shared measurement system and creating opportunities for knowledge exchange. With that in mind, we propose a six-component learning and improvement strategy that involves (1) prioritizing learning needs, (2) mapping needs to evidence, (3) using relevant data-collection methods, (4) analyzing and synthesizing data, (5) feeding data back to CCDP staff and teams and (6) taking action. Initial learning needs include investigating partnership reach and the unanticipated effects of multi-sectoral partnerships for individuals, groups, organizations or communities.

Conclusion:

While the CCDP is the primary audience for the learning and improvement strategy, it may prove useful for a range of audiences, including other government departments and external organizations interested in capturing and sharing new knowledge generated from multi-sectoral partnerships.

Keywords: multisectoral partnerships, collaboration, continuous improvement, learning

Highlights

Multi-sectoral partnerships for complex health issues are not new, yet our understanding of them is limited.

The authors created a learning and improvement strategy to maximize the knowledge and impact of PHAC’s multi-sectoral partnership initiative and to explore novel and time-sensitive questions not routinely captured through monitoring and evaluation.

The strategy highlights the importance of understanding partnership impacts, developing a shared vision, implementing a shared measurement system and creating opportunities for knowledge exchange.

This strategy will help collect relevant, timely data to improve PHAC efforts and contribute to the evidence base on multi-sectoral partnerships for use by a range of audiences.

Introduction

Co-operative and co-ordinated action across multiple sectors, including public and private institutions, is required to effectively address the most challenging public health issues, including the primary prevention of chronic diseases.1-4 These joint efforts are built on the premise that no individual organization or sector has the sole responsibility or capacity for improving population health. It is only through collaborative ventures that make best use of available resources, skills and talents that lasting advancements may be made in the prevention and control of chronic diseases such as cancers, heart disease and mental illness.4-8

Consistent with this perspective, the Public Health Agency of Canada’s (PHAC) Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention (CCDP) launched the Multi-sectoral Partnerships to Promote Healthy Living and Prevent Chronic Disease initiative in 2013 (http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/fo-fc/mspphl-pppmvs-eng.php). This initiative supports multiple partnership projects involving public and private organizations to advance the use of evidence-informed interventions that address common risk factors for chronic disease.9 To maximize the insights from this initiative, the CCDP has developed a learning and improvement strategy that will explore novel and time-sensitive questions not routinely captured through monitoring and evaluation.

This article describes the components of the learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships, the procedures used for its development, and the CCDP’s initial learning priorities.

Multi-sectoral Partnerships to Promote Healthy Living and Prevent Chronic Disease

The Multi-sectoral Partnerships to Promote Healthy Living and Prevent Chronic Disease initiative, administered by the CCDP, matches federal investments with those of private, not-for-profit and charitable sectors to diversify and increase the financial investments in chronic disease prevention, to share potential risks and mutual benefits among participating organizations and to increase the reach and impact of chronic disease prevention interventions. The initiative enables partners to co-create, co-invest and, increasingly, to co-manage projects.

To implement this initiative, the CCDP has transformed certain elements of its grants and contributions investments. For example, it has moved away from a traditional, time-limited solicitation, where applicants would be accepted only at certain times each year, to a two-step continuous intake that allows for ongoing partnership and project development. In addition, a pay-for-performance model has been implemented to improve program accountability: payments are made when jointly negotiated project milestones are reached. Milestone payments are based on project outputs and can include implementing an intervention in an agreed number of locations, completing evaluation requirements (e.g. submitting all baseline data) or developing project resources (e.g. a web portal, mobile app or trainer hub that support overall project goals). Further, to support the development of a strong evidence base for funded projects, the CCDP has put into place a way to consistently collect data on behaviour change, with options for projects to explore social return on investment.

Since launching in February 2013, the initiative has implemented 22 partnership projects (targeting physical activity, healthy living, tobacco use and injury prevention or addressing multiple risk factors) and has secured more than $38 million in leveraged funds.

Benefits and challenges of multi-sectoral partnerships

While multi-sectoral partnerships are important parts of the public health infrastructure in Canada and elsewhere,10-16 what remains challenging is defining what constitutes a partnership; managing their risks and benefits; assessing their structures, processes and outcomes; and improving their performance.

Partnerships are often considered to be dyadic connections between organizations that involve “the sharing of power, work, support and/or information with others for the achievement of joint goals and/or mutual benefits.”17 ,p.61 These connections are the foundations of other collaborative structures, including networks (“a group of three or more organizations connected in ways that facilitate achievement of a common goal”4); alliances (which “typically refer to dyadic partnerships that are simpler and short term in nature than is seen in networks”4); and community coalitions (which “represent defined communities and their memberships and reflect the diversity and wisdom of those communities at both grassroots and “grasstops” [professional] levels.”18 Within each collaborative structure, participating organizations demonstrate similarities and differences in three dimensions: the sectors they represent, the resources they bring and their particular area of focus.

Despite differences between these collaborative initiatives, partnerships share a range of benefits and risks. This is particularly the case with those partnerships that involve public and private organizations, such as Right to Play Canada, Partnership for a Healthier America, Canadian Active After School Partnership and Let’s Move! Active Schools.1-3,19-28 Cited benefits include a greater capacity to share risks and benefits; reaching more target individuals, organizations, sectors and communities; and, through partnership agreements, improved cross-sector engagement and accountability among all participating organizations.2 For partnerships that involve large private organizations, concerns exist over industry partners’ motivations and potential conflicts of interest; mismatches between private company products and community needs; distortion of government priorities by private sector interests; negative impacts on reputation, particularly for public or non-profit sectors; power imbalances between partner organizations; and loss of autonomy, particularly for less powerful partners.1,23 Developing, evaluating and sharing the experiences of those involved in brokering, managing and monitoring multi-sectoral partnerships is therefore an important step toward improving our understanding of how such partnerships operate in different settings and with different partners and their short- and long-term impacts on people and populations.

An opportunity for learning and improvement

On behalf of the Public Health Agency of Canada and consistent with its imperative for evidence-informed action, the CCDP is investing in a learning and improvement strategy to improve their understanding of multi-sectoral partnerships in public health for continuous improvement and to strengthen the evidence base related to partnerships. Other centres within PHAC; other departments, agencies, crown corporations or special operating agencies within the government; or other organizations (e.g. research funding agencies, universities, philanthropic foundations, private industries) with interests/responsibilities in learning about and improving multi-sectoral partnerships will also gain from this strategy. There are strong disciplinary traditions for this work, including organizational learning, that highlight the processes that enable individuals and institutions to change their mental models, norms, strategies and assumptions.29,30 As Senge29 noted, learning organizations are those … “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together.”29,p.3 Drawing on those factors known to influence learning organizations (e.g. team learning, systems thinking, building shared vision), this article describes the development and key elements of the CCDP’s learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships, and outlines initial priorities for implementation.29,30

Methods

The development of the learning and improvement strategy was informed by

CCDP staff involved in the initial design and implementation of the multi-sectoral partnerships initiative and

a review of conceptual frameworks of multi-sectoral partnerships.

Consultations with CCDP staff

Consultations with the CCDP staff, led by CDW and JKG, were conducted on 21 March, 2014. A consultation guide was developed based on discussions with project leads and reviews of CCDP orientation materials (i.e. Partnership Guide, Decision-Making Framework to Assessing Potential Partners, Guidance for Contribution Funding Recipients (Measuring Impact)), and recent PHAC and policy documents. The consultation guide contained a series of questions to elicit participants’ experiences with multi-sectoral partnerships, the intended impacts of PHAC’s multi-sectoral initiative, the strengths and challenges of the existing partnership’s monitoring and evaluation approaches, the areas of uncertainty that may be addressed through existing literature on multi-sectoral partnerships, the initial learning priorities, and the desirable characteristics of a learning and improvement initiative for the CCDP’s multi-sectoral partnerships.

Seventeen CCDP staff members participated in the consultations through four focus groups, each with two to ten participants. Relevant groups were identified as those with existing knowledge and experiences in implementing or evaluating the multi-sectoral partnership initiative. Based on these criteria, individuals from the following groups were invited to participate in focus groups: those with broad oversight of the program (Director General and Senior Director); members of the Partnerships and Strategies Division; members of the Performance Measurement Division; and members of the Interventions and Best Practices Division.

The notes from the four in-person focus group discussions, cofacilitated by CDW and JG, were consolidated into a single file. A thematic analysis was performed across all focus groups to eliminate redundancies and allow overarching themes to emerge. Key themes of interest were identified by multiple groups across the consultations or considered very important by senior leadership teams. These emerging themes were discussed and refined with a working group of eight CCDP employees who were also involved in the focus groups. These individuals were selected based on their different roles and responsibilities (e.g. partnership brokering, evaluation, ongoing management and monitoring, contracts), their depth of knowledge and experience; and their ability to foster change.

Review of conceptual frameworks relevant to multi-sectoral partnerships

With the findings from the consultations, the CCDP working group and researchers from the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact jointly developed the aim of the review: to identify and describe relevant frameworks and/or conceptual models useful for understanding and explaining the characteristics, functions and impacts (intended and unintended) of multi-sectoral partnerships. For the purpose of this review, partnerships could be dyadic connections between organizations (from any sector) as well as connections between more organizations (often considered an inter-organizational network.

Search strategy

We limited our search strategy to peerreviewed and grey literature published in English and in 2000 or later and searched five electronic databases: PubMed, Academic Search Premier, ABI/Inform, Scopus and Web of Science. The strategy, adapted to each database, used a combination of controlled vocabulary and free-text terms (see Table 1). Search terms were grouped into three broad categories to do with frameworks or models, multi-sectoral initiatives and organizational partnerships. Searches for each group were conducted individually and then combined to identify conceptual models relevant to partnerships with multi-sectoral representatives.

TABLE 1. Search term groupings.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|

| framework | multi-sectoral | partnership |

| model | multi-stakeholder | network |

| concept | inter-organizational | collaborative |

| method | interagency | platform |

| theory | inter-sectoral | alliance |

| theories | cross-sectoral | system |

| impact | ||

| effectiveness | ||

| outcome | ||

| performance |

A reviewer removed irrelevant articles based on an initial screen of article titles and two reviewers screened the abstracts of the remaining articles, resolving any disagreements via open discussion. (See Table 2 for the inclusion and exclusion criteria used.) Articles that did not describe a framework, conceptual model or theoretical model relevant to understanding multi-sectoral work and/or multi-organizational work or that had a sole focus on a clinical issue or group (e.g. disease specific, targeting a professional group) were excluded.

TABLE 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Document describes a framework, conceptual model or theoretical model relevant to understanding multi-sectoral work and/or multi-organizational work | Article does not describe a framework, conceptual model or theoretical model |

| Document describes a framework, conceptual model or theoretical model that was not related to understanding multi-sectoral or multi-organizational work | |

| Document focusses solely on a clinical issue or group (e.g. disease specific, targeting a professional group) |

We also conducted a grey literature search of the websites of the FSG, the National Collaborating Centre Methods and Tools, Stanford Social Innovation Review and Tamarack Institute for Community Engagement for reports and publications that described the application of relevant frameworks to multi-sectoral initiatives and/or the development of learning and improvement strategies for multi-sectoral partnerships. In addition, we did an Internet search using Google (https://www.google.ca/) and DuckDuckGo (https://duckduckgo.com/) for combinations of key terms from the database search. The team reviewed the first five pages of each search and identified relevant documents. We applied the same criteria used for screening peer-reviewed literature to the website review and Internet search (Table 2).

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted the following information from each of the relevant documents identified in the search: framework name; framework purpose and/or perspective; critical components/success factors; and domains of evaluation (including examples of respective indicators, where provided). We grouped frameworks according to macro-, meso- and micro-perspectives. Macro-level frameworks provide high-level guidance to understand the social impact of multi-sectoral collaboration. Meso-level frameworks describe how collaboration works and the factors that are important for organizing partnerships. Micro-level frameworks provide the broad domains necessary for understanding how partnerships work as well as more specific, individual indicators, tools or measures of partnership activity.

We categorized frameworks with elements from more than one level according to the highest level of application.

Information for each framework was extracted, tabulated and summarized using a narrative initiative.

Development of the learning and improvement strategy

During consultations, CCDP staff began to uncover the practical challenges of brokering, implementing and evaluating multisectoral partnerships and the broad areas where information is not routinely gathered during standard monitoring and evaluation activities. CCDP staff were also interested in improving their understanding of the critical success factors of interorganizational partnerships, key measurement domains and partnership performance assessment techniques. Based on these interests, the literature review focussed on partnership frameworks that summarized the concepts that relate to multi-sectoral partnerships. To blend the practical insights gained from the CCDP consultations with the conceptual insights from the literature review, we developed an overarching strategy that built on current knowledge of multisectoral partnerships and responded to the specific needs of CCDP staff. Information about learning cycles31 and continuous quality improvement32 helped generate a strategy that is flexible, iterative and tailored to the specific context of multi-sectoral partnerships, with 3- to 4-month long prioritized learning cycles that ensure responsiveness to time-sensitive issues and the best use of existing resources.

A draft strategy was developed by the joint CCDP–Propel team and refined through discussions with 33 members of the CCDP.

Results

Consultations

The consultations identified a range of concepts, ideas and needs related PHAC’s multi-sectoral partnership initiative, including understanding partnership impact, design, performance, development and improvement. In particular, the consultation process highlighted three key themes:

Some of the impacts of the multi-sectoral partnership initiative and its projects are captured in the short- and long-term outcomes measured by the initiative’s performance measurement system. Others may include leverage (e.g. resources, skills, reputation, credibility, funds), program reach, sustainability of interventions, support of social innovation, social return on investment and PHAC credibility (both internal and external to government). Multiple effects, both positive and negative, may exist, for example, greater capacity within partnering organizations (e.g. in generating social value); new staff skills built in partnering organizations (e.g. in evaluation skills); improved use of technology (e.g. improving data capture and monitoring techniques); potential widening of health inequalities based on socioeconomic conditions, culture or geographic location; and restrictive focus on individual health practices rather than population health approaches.

The CCDP (e.g. in the Partnerships and Strategies Division and the Executive Office, among senior managers) has a wealth of practice-based knowledge on types of partners and partnerships, what works for these partnerships (and what does not), for whom this is working, under what circumstances and why. This knowledge relates to how to initiate, establish, support, modify, measure, govern and assess multi-sectoral partnerships at different stages of development, as well as how the organizational structure or design of the CCDP and PHAC helps or hinders existing practice. Tools, templates and processes to inform decision-making exist; however, highly relevant practitioner knowledge is not being systematically captured, shared or used to explain, understand and improve multi-sectoral partnerships.

Given the current focus on implementing the multi-sectoral partnership initiative and its projects, there have been few opportunities to reflect, learn and act on the existing knowledge, assets and experiences within the CCDP. This includes identifying and filling gaps in knowledge, skills and training—and in a timely fashion. Given PHAC’s mandate, the natural experiment provided by the multi-sectoral initiative and the growing call for new knowledge on cross-sector engagement for population health improvement, the need to reflect on and learn about experiences in real time was considered particularly important.

Frameworks review

The search strategy identified 5363 articles, of which 5066 were screened out following a review of titles, leaving 297 for abstract/full text review. During the full text review, 204 were excluded, leaving 93. We screened search results a second time to identify the most relevant and recent articles and eliminate duplication and excluded 17 papers published before 2007. Finally, we reviewed the remaining 76 papers for relevancy and/or inclusion of the equivalent of a framework and excluded 56.

The grey literature search identified 26 documents, of which 12 were excluded as per set criteria, for a total of 14.

In total, we reviewed 34 articles on 19 unique frameworks relevant to developing a learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships. Table 3 lists the 19 macro, meso- and micro-level frameworks included in this review.

TABLE 3. Macro-, meso- and micro-level frameworks.

| Macro-level frameworks | Meso-level frameworks | Micro-level frameworks |

|---|---|---|

| Social innovation | Systems change framework | Propositional inventory for the design and implementation of cross-sectoral collaboration (specific application in leadership) |

| Shared value | Framework to guide strategy development for non-profit organizations | Framework and process for collaborative action in public health |

| Collective impact | Grounded model for analyzing formation in cross-sectoral work | RE-AIM framework for impact assessment of multi-sectoral partnerships |

| Propositional inventory for the design and implementation of cross-sectoral collaboration | The collaboration and evaluation and improvement framework | |

| An integrated framework for collaborative governance | Framework for understanding the performance effects of inter-organizational networks | |

| Framework of organizational outcomes for community collaboration | Framework for assessing effectiveness of health promotion networks | |

| Framework of antecedents, process and perceived effectiveness of inter-organizational collaborations for public service delivery | Multi-level performance indicators for multi-sectoral networks and management | |

| Collaborative value creation framework for analyzing non-profit and business partnerships | ||

| Key initiatives and frameworks for health and social care partnerships |

Macro-level frameworks

These frameworks describe the role of collaboration in driving positive social change and the factors critical to assessing large-scale change initiatives. Such frameworks may help capture and describe the broad goals of PHAC’s multi-sectoral initiative, which can then be linked to specific aspects of funded partnership projects. Macro-level frameworks include social innovation,33,34 shared value35-37 and collective impact.38-42 (Note: we have clustered collective impact with other macro-level frameworks; however, we recognize that it demonstrates characteristics consistent with meso- and micro-level frameworks.) While a full discussion of each framework is beyond the scope of this review, this summary highlights each framework’s key perspectives, how it positions multi-sectoral work and the insights it provides into learning and improvement strategies for multi-sectoral partnerships.

Social innovation is described as the pursuit of “a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, sustainable or just than existing solutions and for which the value created accrues primarily to society as a whole rather than private individuals.”43 Le Ber and Branzei34 illustrated that partnerships are a critical component of social innovation and highlight the importance of relational attachment between partners, partner complacency and partner disillusionment. Nurturing multi-sectoral relationships requires partners to continually re-align roles and relationships as contexts, circumstances and conditions change.

In contrast, shared value promotes investments in long-term business competitiveness while promoting social and environmental objectives.35 For those partnerships convened to generate shared value, multi-sectoral partnerships are thought to provide critical tools for achieving both business outcomes (e.g. increased revenue, market share, profitability) and social outcomes (e.g. improved care of patients, reduced carbon footprint, improved job skills).37

Compared to shared value and social innovation frameworks, collective impact focusses on multi-sectoral partnerships, which are thought to be influenced by five core conditions: a common agenda; shared measurement systems; reinforcing activities; continuous communication; and the support of a backbone organization.39-41 Underlying the success of collective impact initiatives is a continuous learning process built on shared measurement and ongoing evaluations, which capture process and outcome indicators matched to the stage of partnership evolution.41

Meso-level frameworks

In this review, we consider meso-level frameworks as those that focus explicitly on the workings of partnerships. The meso-level frameworks listed in Table 3 differ in their specific focus, such as the formation of partnerships, the success factors that drive them and the expected outcomes/impacts. Common themes across the frameworks relate to the importance of context; the need to clearly identify the problem; the processes necessary for building and maintaining partner engagement; the importance of understanding and interacting; and links to partnership outcomes.

Context

Context may be considered from both an outer and inner perspective. Outer context is the external setting, including the norms, resources, regulations and operations of societies, as well as existing policy, political and legal conditions that affect a partnership.12,44,45

Inner context includes existing corporate and organizational cultures, structures and policies that may be influenced by organizational members12 and how the characteristics of individual organizations and history of interactions influence partnerships and their outcomes.46

Identifying and framing the problem

Multiple meso-level frameworks highlight how important it is to understand the issue or problem the multi-sectoral partnership is addressing as well as its boundaries (i.e. what is contained in the given system, such as organizations, relationships, histories and cultures).44 Successful partnerships engage different stakeholder groups in an explicit process that aims to understand diverse perspectives; this may include developing purpose statements and mandates, committing resources and agreeing on decision-making structures.13,44

Partnership processes

Partnership processes form the daily activities of partnership work and involve forging agreements, building leadership and legitimacy, fostering trust among partners, managing conflict and planning for ongoing partnership activities.13 The collaborative value creation framework matches partnership processes with stages of partnership evolution; it suggests that, as collaborative structures move toward transformational forms, relationship structures shift to more sharing of resources, more intense interactions, higher strategic values and greater engagement in opportunities for innovation.10,11 Specific processes may include delivering educational/training sessions, marshalling external resources or monitoring implementation activities.45 Within the different stages of partnership development (e.g. formation, selection, implementation, design and operations, institutionalization), many subprocesses exist, such as mechanisms for mapping organizational fit, undertaking formal and informal risk management processes and exploring different structures and design features to enable experimentation in the pursuit of shared value (such as convening groups for joint decision making, building trust and navigating organizational autonomy47).

Interactions

Many frameworks recommend examining interactions between components of partnerships to understand and improve the function of the partnership. Interactions may be understood by examining inter-organizational alignment; relative strengths and weaknesses of organizations (competitors and collaborators); barriers between organizations; and power imbalances.12 The Systems Change Framework identifies distinct processes for examining interactions between system parts, including how these interactions may be used to identify points for leveraging change.44 Introducing processes that map interactions between organizations may be an important step towards a more sophisticated understanding of how multi-sectoral relationships operate within broader social contexts.

Partnership outcomes

Partnership outcomes may be considered as first order outcomes (short-term results of partnership work); second order outcomes (e.g. co-ordinated action, changes in practice or changes in perceptions); and third order outcomes (e.g. co-evolution, the formation of new institutions, and new norms).13 Outcomes may also include intentional and unintentional changes in desired states, the development of new social goods or technological innovations, improved inter-organizational learning, increased interaction among organizational members, greater capacity to access resources, increased ability to serve clients (if service provision is an activity) and improved problem-solving capacity.48 Given this diversity, it is critical that outcome measures are appropriate for a given partnership and its stage of development.

Micro-level frameworks

Micro-level frameworks provide the broad domains necessary for understanding partnership work as well as more specific indicators of partnership activity (including specific data-collection tools).

Of the micro-level frameworks reviewed, three relate to inter-organizational networks,49-51 while the remainder are more broadly relevant to collaboration and partnerships. From this broader perspective, the framework and processes for collaborative action in public health identify five domains necessary for partnership work: assessment and collaborative planning; implementing targeted actions, changing conditions in communities and systems, achieving change in behaviour, and improving health and health equity.52 These domains include explicit indicators of success, such as the presence of a common purpose, clearly articulated logic models, explicit roles, and designated and distributed leadership.

While long-standing challenges exist in establishing causal links between network co-ordination and performance, Gulati et al.49 proposed three domains for understanding network success—reach, richness and receptivity—and provide specific indicators for each, such as distance between partners, trust, commitment and tie multiplexity. In contrast, the Health Promotion Networks Framework focusses on structure, process and effectiveness,50 with potential indicators including age, size and network form; processes facilitated by the network, such as advocacy, training and raising public awareness; effects to do with organizational learning; and changes in practice. Finally, the Collaborative Evaluation Improvement Framework53 describes specific data-collection strategies for mapping network effectiveness: mapping team and decision-making procedures; conducting interviews, surveys and document analyses to better understand internal processes; and collecting data on the quality of team interactions through specific tools (e.g. Levels of Organizational Integration Rubric (LOIR)53 and the Team Collaboration Assessment Rubric (TCAR)53).

Learning and improvement strategy

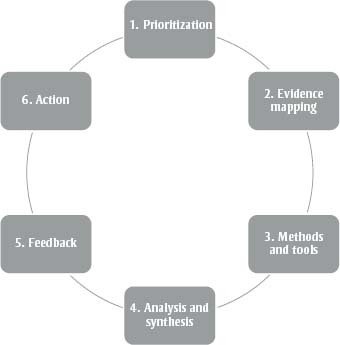

Figure 1 shows the CCDP’s six-phase learning and improvement strategy for the multi-sectoral partnerships initiative. These learning cycles, mapped to Kolb’s stages of learning (feeling, observing, thinking and doing),31 enable the CCDP to rapidly prioritize guiding questions relevant to multi-sectoral partnerships, collect and analyze necessary information informed by evidence-based practice and package information in formats useable to CCDP staff (and potentially others).

FIGURE 1. Components of a learning and improvement strategy.

1. Prioritization—Refining and prioritizing learning and improvement needs to do with multi-sectoral partnerships.

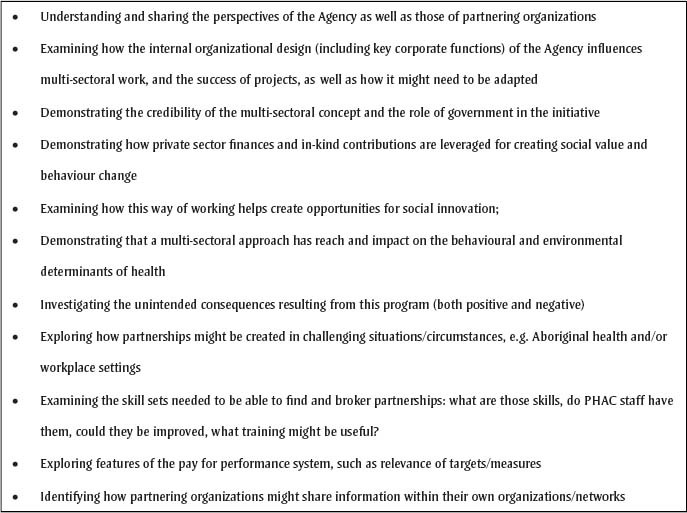

Initial consultations with CCDP staff provided an overview of the CCDP’s multi-sectoral initiative and helped identify a number of potential directions for learning and improvement (see Figure 2). These learning needs, informed by the initial assumptions guiding the multi-sectoral initiative (e.g. improving reach, use of resources and amplifying impact), provide useful starting points for developing specific questions to explore through a learning and improvement strategy. Ongoing development of these questions requires engaging with individuals and teams from the CCDP and, potentially, with organizations partnering with the CCDP through multi-sectoral partnership projects. Such prioritization processes may involve in-person workshops or modified Delphi processes for gathering large group perspectives.54

FIGURE 2. Initial learning needs.

2. Evidence mapping—Mapping of prioritized learning needs against existing partnership frameworks.

Phase 2 draws on relevant literature to help decide how the CCDP’s learning needs will be addressed, including how problems would be defined and solved. This involves mapping prioritized areas to relevant partnership frameworks using a number of alignment criteria, including the level at which information is desired, the stage of partnership evolution and the level of detail required. For example, a key learning need for the CCDP relates to understanding the reach of existing multi-sectoral partnership projects. Initial mapping to conceptual partnership frameworks helps identify different aspects of reach (e.g. to target individuals, organizations, sectors, communities), factors influencing the reach and how this knowledge may be used to continuously improve the CCDP’s partnership initiative.

3. Methods and tools—Identifying methods and tools for gathering information to address multi-sectoral partnership learning needs.

The reviewed frameworks provide direction on how a learning need of a multi-sectoral engagement might be framed, as well as the tools for gathering relevant data. Among the primary considerations are the levels at which information is sought (broad initiative, project and/or organization) and the stage of development of the partnership project. According to the literature on learning organizations, organizational-level information may focus on organizational roles, internal organizational structures and processes, organizational benefits from partnering or organizational learning culture. For example, for the CCDP’s initial learning priority, which focussed on reach, relevant information may be collected from existing assets, including existing project reports and key informant interviews with CCDP, PHAC staff and external partners.

For project-level information, key foci may include mapping inter-organizational relationships within partnership projects; identifying and mapping communities of practice within partnership projects; and monitoring stages of collaboration within partnership projects. These domains may be explored to understand how individuals and organizations within partnership projects work with each other; the available communication channels; and the frequency and intensity of communications within partnership projects.55 To gather information about these project-level foci, newer data-collection approaches (such as social network analyses) may be useful alongside traditional qualitative and quantitative techniques.53

At the broad initiative level, information from across the suite of partnership projects may be required to provide the CCDP with insights into the early stages of partnership formation, including the core conditions (and linked indicators) of collective impact, such as shared agenda setting and shared measurement. To capture information on the CCDP’s multi-sectoral initiative, relevant indicators may include how partners and the broader community understand and articulate the problem; the degree to which partners understand how they will participate in the shared measurement system; and observed changes in partners’ activities to align with the shared plan of action.41 In contrast, for partnerships at mid/late stages of development, initiative-level information may focus more on outcomes using techniques such as outcome mapping or “most significant change” to help describe initiative impacts.56 This learning and improvement strategy provides the CCDP with important opportunities to develop, test and refine indicators for measuring partnership effectiveness.

4. Analysis and synthesis—Analyzing and synthesizing information: using relevant analytical lenses.

Phase 4 of the strategy applies relevant and rigorous methods for analyzing and synthesizing diverse information from different settings and methodologies. For example, realist synthesis can help build an understanding of what works, as well as how and why different activities produce certain effects in specific settings.57 Applying a realist lens helps bring together a diverse set of evidence and generates policy guidance that may serve as a useful input into group sense-making discussions (the collective interpretation of new information) for the CCDP. Using feedback to connect information with relevant individuals and groups to promote understanding, questioning, problem solving and application to the CCDP’s partnership practice.

A key component of the learning cycle initiative is to ensure information is accessible to relevant audiences. While the primary audience of the learning and improvement strategy is the CCDP itself, the proposed learning cycles will allow feedback from other relevant groups and individuals (in and outside government). These options may involve writing technical reports, publications, interactive online maps, etc.; presenting to various CCDP team members as well as individuals in other sectors and other levels of government; and running workshops with different combinations of groups as information is interpreted and negotiated.

5. and 6. Feedback and Action—Including redesigning internal processes, structures, evaluation strategies and engagement options for multi-sectoral partnerships.

Through feedback sessions at the end of each learning cycle (Phase 5), individuals and groups at the CCDP can align new learning with potential organizational, policy and practice changes. These may include redesigning internal CCDP processes, modifying partnership brokering techniques, developing new training modules, implementing new or revised partnership governance mechanisms or revising impact and outcome assessment procedures. Each action may influence the priority learning domains (as noted in Phase 1), thereby shifting the focus for the next learning cycle. By being this flexible, the CCDP’s learning and improvement strategy will remain relevant to and useful for changes in multi-sectoral partnership projects.

Discussion

Inter-organizational partnerships are an important part of Canada’s initiative to address complex public health problems through preventing chronic diseases, improving healthy living and reducing health inequalities.1,9 These partnerships try to increase the reach of evidence-based programs, leverage new resources and foster change in the health and cultures of communities and partnering organizations. This focus on partnership engagement is consistent with a recent Speech from the Throne, which signalled the government’s intent to act “…on the opportunities presented by social finance and the successful National Call for Concepts for Social Finance.” 58

The CCDP’s multi-sectoral initiative, which involves many traditional and non-traditional partners, is trying to achieve social and economic gains by harnessing the expertise, resources and reach of diverse partners. In this article, we describe the CCDP’s approach to developing a learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships. While the intended user of this strategy is the CCDP itself, the strategy may be applied to other government and non-governmental groups and agencies.

The evidence-informed learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships we outline here is consistent with current perspectives of population health intervention research.59,60 The CCDP’s multi-sectoral partnership initiative carries the hallmarks of a population health intervention: action is preceding the science; innovations are being implemented by a team responsible for policy and practice; a broad range of relevant knowledge is used to shape and understand the initiative; the effort is underpinned by a desire for large-scale social change; and the outcomes of the initiative require time to emerge.61 Counter to hypothesis-driven research methodologies, this type of population health intervention calls for an embedded research design that is able to rigorously capture, assess and share how such practices work, under what conditions, for whom and why.61 It is this “learn as we go” philosophy that has informed the genesis of the CCDP’s learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships, and which is likely relevant to other government initiatives, including those of PHAC and other government departments. Initial learning priorities, which focussed on understanding partnership reach, intended and unintended effects, and capturing practice-based knowledge, stand to make important contributions to the scientific literature related to partnerships, as well as enhance the CCDP’s multi-sectoral partnership improvement efforts and the nascent efforts of other government departments in this area.

Strengths and limitations

This study has two primary limitations. First, consultations were restricted to CCDP staff and so the perspectives and experiences of others in the multi-sectoral partnership initiative have not been captured. As the learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships is implemented, it will be important to broaden the range of participants and include those from other branches and divisions of PHAC and from partnering organizations. Plans are in place to capture these perspectives, as they relate to reach, through data collection with external partners (from public and private sectors).

Second, the review of published frameworks, while systematic, may not be comprehensive, and there may be other relevant frameworks and models that we did not include in this study. Nevertheless, the frameworks we reviewed provide a diverse set of perspectives on the structures, functions and outcomes of multi-sectoral partnerships.

A first cycle of the strategy will focus on understanding the reach of existing partnership projects and a second on the unanticipated effects (positive and negative) of different partnership projects. Findings from both cycles will contribute to ongoing efforts to capture and learn from the practical experiences of those in the partnership initiative.

Conclusions

In this article, we outline the CCDP’s approach to learning from and improving its multi-sectoral partnership initiative projects. The strategy described here provides the CCDP, and potentially others, with an evidence-informed, practical and flexible means for identifying and addressing key learning needs related to multi-sectoral partnerships in ways that meet the time-sensitive demands of those seeking to influence public policy. Multi-sectoral partnerships for complex health issues are not new, yet our understanding of them is limited. Ideally, the learning and improvement strategy for multi-sectoral partnerships described in this article will help the CCDP and others identify and fill key knowledge gaps and advance the capacity of multi-sectoral initiatives to address pressing health concerns that affect Canadians.

References

- 1.Johnston LM, Finegood DT. Cross-Sector partnerships and public health: challenges and opportunities for addressing obesity and noncommunicable diseases through engagement with the private sector. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:255–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122802. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woulfe J, Oliver TR, Zahner SJ, Siemering KQ. Multisector partnerships in population health improvement. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7((6)):A119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reich MR. Cambridge (MA): Harvard Centre for Population Development Studies; 2002. Public-private partnerships for public health. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provan KG, Fish A, Sydow J. Interorganizational networks at the network level: a review of the empirical literature on whole networks. J Manage. 2007;33((3)):479–516. doi: 10.1177/0149206307302554. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Provan KG, Beagles JE, Leischow SJ. Network formation, governance, and evolution in public health: the North American Quitline Consortium case. Health Care Manage Rev. 2011;36((4)):315–26. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31820e1124. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31820e1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Provan KG, Lemaire R. Core concepts and key ideas for understanding public sector organizational networks: using research to inform scholarship and practice. Public Adm Rev. 2012;72((5)):638–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02595.x. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willis CD, Riley BL, Best A, Ongolo-Zogo P. Strengthening health systems through networks: the need for measurement and feedback. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27( Suppl 4):62–6. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis CD, Riley BL, Herbert CP, Best A. Networks to strengthen health systems for chronic disease prevention [Internet] Am J Public Health. 2013;103((11)):e39–e48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Health Agency of Canada . Multi-sectoral Partnerships to promote healthy living and prevent chronic disease. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. [cited 2014 May 23]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/fo-fc/mspphl-pppmvs-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin JE, Seitanidi MM. Collaborative value creation: a review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2. Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprof Volunt Sec Q. 2012;41((6)):929–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin JE, Seitanidi MM. Collaborative value creation: a review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 1. Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonpro Volunt Sec Q. 2012;41((5)):726–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Tabbaa O, Leach D, March J. (3) Vol. 25. Voluntas: Int J Volunt Nonprof Org; 2013. Collaboration between nonprofit and business sectors: a framework to guide strategy development for nonprofit organizations; pp. 657–78. doi: 10.1007/s11266-013-9357-6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryson JM, Crosby BC, Stone MM. The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: propositions from the literature. Public Admin Rev. 2006;66((SUPPL. 1)):44–55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman SR, Reynolds J, Quan MA, Call S, Crusto CA, Kaufman JS. Measuring changes in interagency collaboration: an examination of the Bridgeport Safe Start Initiative. Eval Program Plann. 2007;30((3)):294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kothari A, Sibbald SL, Wathen CN. Evaluation of partnerships in a transnational family violence prevention network using an integrated knowledge translation and exchange model: a mixed methods study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12((1)):25. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-25. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumaresan J, Heitkamp P, Smith I, Billo N. Global Partnership to Stop TB: a model of an effective public health partnership. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8((1)):120–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kernaghan K. Partnership and public administration: conceptual and practical considerations. Can Public Admin. 1993;36((1)):57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butterfoss FD. Coalitions and partnerships in community health. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asante AD, Zwi AB. Public-private partnerships and global health equity: prospects and challlenges. Indian J Med Ethics. 2007;4((4)):176–80. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2007.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barr DA. Ethics in public health research: a research protocol to evaluate the effectiveness of public-private partnerships as a means to improve health and welfare systems worldwide. Am J Public Health. 2007;97((1)):19–25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bate SP, Robert G. Knowledge management and communities of practice in the private sector: Lessons for modernizing the NHS in England and Wales. Public Administration. 2002;80:643–63. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00322. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaglehole R, Ebrahim S, Reddy S, Voute J, Leeder S. Prevention of chronic diseases: a call to action. Lancet. 2007;370((9605)):2152–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61700-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galea G, McKee M. Public-private partnerships with large corporations: setting the ground rules for better health. Health Policy. 2014;115((2-3)):138–40. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.02.003. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leenaars K, Jacobs-van der Bruggen M, Renders C. Determinants of successful public-private partnerships in the context of overweight prevention in Dutch youth. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E117.. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120317. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannar MG, van Ameringen M. Role of public-private partnership in micronutrient food fortification. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24((4 Suppl)):151–4. doi: 10.1177/15648265030244S213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rummery K. Healthy partnerships, healthy citizens? An international review of partnerships in health and social care and patient/user outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69((12)):1797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.004. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiner BJ, Alexander JA. The challenges of governing public-private community health partnerships. Health Care Manage Rev. 1998;23((2)):39–55. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Widdus R. Public-private partnerships: an overview. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99( Suppl 1):S1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senge PM. The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Currency; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senge PM, Sterman JD. Systems thinking and organizational learning: acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. Eur J Oper Res. 1992;59:137–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deming WE. Out of the crisis. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cajaiba-Santana G. Social innovation: moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technol Forecast Soc. 2014;82((0)):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Ber MJ, Branzei O. (Re)forming strategic cross-sector partnerships: Relational processes of social innovation. Bus Soc. 2010;49((1)):140–72. doi: 10.1177/0007650309345457. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter M, Kramer M. Harvard Bus Rev. 2011 Jan/Feb. Creating shared value. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porter ME, Hills G, Pfitzer M, Patscheke S, Hawkins E. Measuring shared value. How to unlock value by linking social and business results. Boston (MA): FSG; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bockstette V, Stamp M. Creating shared value: a how-to guide for the new corporate (r)evolution. Boston (MA): FSG; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanleybrown F, Kania J, Kramer M. Channeling change: making collective impact work [Internet]. Stanford Soc Innov Rev; ; 2012. [cited 2015 Apr 21]. Available from: http://ssir.org/articles/entry/channeling_change_making_collective_impact_work. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kania J, Kramer M. Embracing emergence: how collective impact addresses complexity. Stanford Soc Innov Rev [Internet]; 2013. [cited 2015 Apr 21]. Available from: http://www.ssireview.org/blog/entry/embracing_emergence_how_collective_impact_addresses_complexity. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact [Internet] Stanford Soc Innov Rev; 2011. [cited 2015 Apr 21]. Available from: http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preskill H, Parkhurst M, Splansky Juster J. Guide to evaluating collecting impact: assessing progress & impact. Boston (MA): Collective Impact Forum; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preskill H, Parkhurst M, Splansky Juster J. Guide to evaluating collecting impact: Learning and evaluation in the collective impact context. Boston (MA): Collective Impact Forum; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phills JA, Deiglmeier K, Miller DT. Rediscovering social innovation [Internet] Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2008;6((4)):34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foster-Fishman PG, Nowell B, Yang H. Putting the system back into systems change: a framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39((3-4)):197–215. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emerson K, Nabatchi T, Balogh S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J Public Admin Res Theor. 2011;22((1)):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seitanidi MM, Koufopoulos DN, Palmer P. Partnership Formation for Change: Indicators for Transformative Potential in Cross Sector Social Partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics. 2010;94((S1)):139–61. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen B. 2010;13((4)):381–407. Antecedents or processes? Determinants of perceived effectiveness of interorganizational collaborations for public service delivery. Int Public Manag J . [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nowell B, Foster-Fishman P. Examining mMulti-Sector Community Collaboratives as Vehicles for Building Organizational Capacity. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;48((3-4)):193–207. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9364-3. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gulati R, Lavie D, Madhavan R. The performance effects of interorganizational networks. Vol. 31. Res Organ Behav.; 2011. How do networks matter? pp. 207–24. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dietscher C. How can the functioning and effectiveness of networks in the settings approach of health promotion be understood, achieved and researched? Health Promot Int. 2013.. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dat067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herranz J. Multilevel performance indicators for multisectoral networks and management. Am Rev Public Admin. 2010;40((4)):445–60. doi: 10.1177/0275074009341662. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fawcett S, Schultz J, Watson-Thompson J, Fox M, Bremby R. Building multi-sectoral partnerships for population health and health equity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7((6)) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woodland RH, Hutton MS. Evaluating organizational collaborations: Suggested entry points and strategies. Am J Eval. 2012;33((3)):366–83. doi: 10.1177/1098214012440028. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi Technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12((10)):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glasby J, Dickinson H, Miller R. Int J Integr Care. 2011. Partnership working in England—where we are now and where we’ve come from. 11 Spec Ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McIsaac E, Van Ymeren J. Demonstrating the results of capacity building: Final report of the Partnerships Grant Learning Project. Toronto (ON): The Mowat NFP; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pawson R. The science of evaluation: a realist manifesto. London (UK): SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canada . Governor General. Speech from the Throne to Open the First Session of the 41st Parliament of Canada. 2013 Oct 16 [cited [cited 2015 Apr 21]. Available from: http://www.lop.parl.gc.ca/ParlInfo/Documents/ThroneSpeech/41-2-e.html. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hawe P, Potvin L. What is population health intervention research? Can J Public Health. 2009;100((1)): Suppl I8–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03405503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56((2)):119–27. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hobin E, Hayward S, Riley BL, Di Ruggiero E, Birdsell J. Maximising the use of evidence: exploring the intersection between population health intervention research and knowledge translation from a Canadian perspective. Evid Pol. 2012;8((1)):97–115. [Google Scholar]