Abstract

This status report on the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP), an emergency department-based injury and poisoning surveillance system, describes the result of migrating from a centralized data entry and coding process to a decentralized process, the web-based eCHIRPP system, in 2011. This secure system is improving the CHIRPP’s overall flexibility and timeliness, which are key attributes of an effective surveillance system. The integrated eCHIRPP platform enables near real-time data entry and access, has user-friendly data management and analysis tools, and allows for easier communication and connectivity across the CHIRPP network through an online collaboration centre. Current pilot testing of automated data monitoring and trend analysis tools—designed to monitor and flag incoming data according to predefined criteria (for example, a new consumer product)—is revealing eCHIRPP’s potential for providing early warnings of new hazards, issues and trends.

Keywords: injury surveillance, injury prevention, informatics, syndromics, epidemiology, public health

Highlights

Multi-sectoral partnerships for complex health issues are not new, yet our understanding of them is limited.

The authors created a learning and improvement strategy to maximize the knowledge and impact of PHAC's multi-sectoral partnership initiative and to explore novel and time-sensitive questions not routinely captured through monitoring and evaluation.

The strategy highlights the importance of understanding partnership impacts, developing a shared vision, implementing a shared measurement system and creating opportunities for knowledge exchange.

This strategy will help collect relevant, timely data to improve PHAC efforts and contribute to the evidence base on multi-sectoral partnerships for use by a range of audiences.

Introduction

Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death among Canadians aged 1 to 44 years and the fifth leading cause of death among all ages combined.1 Most injury events are not unavoidable accidents but are predictable and preventable.2

Health surveillance is the systematic, ongoing collection of health information and its analysis, interpretation and dissemination to make it meaningful and accessible.3,4 Injury surveillance is vital to understanding the circumstances leading to the injuries; knowing these circumstances leads to their prevention via early warnings of new hazards and trends, public awareness campaigns and product safety legislation. Surveillance systems must therefore be dynamic3 and evolve with changing behaviours, hazards, environments, technology and other factors. Flexibility and timeliness are key attributes of a good surveillance system.3 Flexibility means that “[t]he system should be easy to change, especially when ongoing evaluation shows that change is necessary or desirable,” and timeliness signifies that “[t]he system should be able to generate up-to-date information whenever that information is needed.”3,p.16-17

Before 1990, national injury surveillance relied mainly on mortality and hospital administrative data. Despite their importance for measuring the incidence of the most serious injuries, these data are limited in their capture of less serious cases and the details of some injury contexts. The Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP) is an emergency department (ED)-based injury and poisoning surveillance system established in 1990 in response to the need for enhanced and timelier injury surveillance information in Canada.

The CHIRPP operates in 11 pediatric and 6 general hospitals across Canada (see Table 1) and is funded and administered by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). It collects patients’ accounts of pre-event injury circumstances (narratives of “what went wrong”) using the Injury/Poisoning Reporting form, a questionnaire completed during a patient's visit to the ED. The attending physician or other staff add clinical data to the form, and data coders extract other information found in patients’ narratives. The CHIRPP captures a more complete picture of the injury event, one that includes risk and protective factors, than do hospital administrative or mortality data alone, and also identifies less serious injury cases that do not require hospitalization.

TABLE 1. Current CHIRPP sites.

| Site | Location | Joined the CHIRPP |

|---|---|---|

| BC Children’s Hospital | Vancouver, B.C. | April 1990 |

| Kelowna General Hospital | Kelowna, B.C. | April 2011 |

| Alberta Children’s Hospital | Calgary, Alta. | April 1990 |

| Stollery Children’s Hospital | Edmonton, Alta. | June 2009 |

| The Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg | Winnipeg, Man. | April 1990 |

| Arctic Bay Health Centre | Arctic Bay, Nun. | January 1991 |

| Children’s Hospital at London Health Sciences Centre | London, Ont. | April 1990 |

| The Hospital for Sick Children | Toronto, Ont. | April 1990 |

| Kingston General Hospital | Kingston, Ont. | June 1993 |

| Hotel Dieu Hospital | Kingston, Ont. | June 1993 |

| Children’s Outpatient Centre, Hotel Dieu Hospital | Kingston, Ont. | September 2011 |

| Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario | Ottawa, Ont. | April 1990 |

| Montreal Children’s Hospital | Montréal, Que. | April 1990 |

| CHU Sainte-Justine, Centre hospitalier universitaire mère-enfant | Montréal, Que. | April 1990 |

| Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus, CHU de Québec | Québec, Que. | July 1991 |

| IWK Health Centre | Halifax, N.S. | April 1990 |

| Janeway Children’s Health and Rehabilitation Centre | St. John’s, N.L. | April 1990 |

| Carbonear General Hospital | Carbonear, N.L. | April 2011 |

Abbreviations: CHIRPP, Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program; CHU, centre hospitalier universitaire.

Since 1990, the CHIRPP database has accumulated nearly three million records, of which approximately 80% are pediatric.

Throughout the program’s 25 years, in collaboration with Health Canada’s Consumer Product Safety Directorate and other organizations, CHIRPP data have been used to develop product safety standards and legislation.5-9 Over 100 scientific papers on a wide variety of topics cite these data.10-16 The CHIRPP on-site directors and co-ordinators are also routinely consulted on shaping injury surveillance and prevention.

Examples of other hospital-based, sentinel injury surveillance systems include the United States’ National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), which produces near real-time data via a network of nearly 100 hospitals,17 and the European Union’s Injury Database (EU-IDB), which provides standardized cross-national information on the external causes of injuries treated in 100 EDs in the European Union.18 Both of these systems can be publicly queried online and have been shown to be flexible.19

In this paper, we describe the CHIRPP’s recent modernization to meet demands for timelier information, continued flexibility, and dynamic and integrated informatics technology that is flexible to changing business needs. (The history of the CHIRPP is described elsewhere.20-22) The evolution of the CHIRPP is also in keeping with the Government of Canada’s agenda to strive to use “new technologies to improve networking and access to data” via “efficient, interconnected and nimble processes, structures and systems.”23

Following a brief description of recent changes to the CHIRPP codebook (a reference manual describing the variables and codes), we discuss the innovative, web-based eCHIRPP platform and its key successes and future directions. Beyond published evaluations of some systems, including the CHIRPP, the information on modernizing injury surveillance systems is scarce.18,19,21,24 The scarcity of knowledge on new technological tools for injury surveillance has also only recently been acknowledged,25 so this is a timely contribution to the discussion.

The CHIRPP codebook

The CHIRPP codebook has remained flexible with changing program needs and information demands. Specifically, the CHIRPP has evolved to reduce redundancies, increase comparability to national and international injury classification and provide more detailed and timely data on essential variables and targeted topics including emerging hazards or issues and changing trends. One example, created in 2010, is an aggregated version of the external cause of injury variable based on the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision,26 which has been useful for producing summary statistics on environmental events and circumstances on the cause of injury. A validation study is planned to assess the comparability of the proportions of CHIRPP’s external cause of injury data to other Canadian and international ICD-10 coded health data. Around the same time, the sports and recreation (SPAR) variable was also created for a more detailed and timely capture and analysis of any SPAR-related activity related to the injury, especially for tracking more severe injuries among youth, especially head injuries. Many new factor codes were also created to identify additional consumer products, including emerging hazards. These are just some of the examples of how the CHIRPP codebook has been modified to remain flexible over time.

CHIRPP gets connected: eCHIRPP

The most significant enhancement to the CHIRPP’s flexibility and timeliness has been an electronic application. Established in 2011, eCHIRPP is one of many integrated, web-based health surveillance applications developed by PHAC’s Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence (CNPHI). CNPHI is “a comprehensive framework of applications and resources designed to fill critical gaps in Canada’s national public health infostructure.”27,p.353 The ultimate goal of the CNPHI is to enhance day-to-day public health delivery by empowering public health stakeholders with innovative scientific public health informatics resources;27 additional objectives of the CNPHI and initiatives to enhance public health surveillance are described elsewhere.28,29

eCHIRPP was designed for much more than data entry alone; it was developed as a single integrated platform to produce timely injury data, user-friendly data management and analysis tools, and easier communication and connectivity across the CHIRPP network and to optimize local injury surveillance at each CHIRPP site. True to CNPHI values, eCHIRPP was developed using a collaborative, program-centric, iterative approach with its end users contributing ideas to increase the application’s functionality.27

The timeliness of data entry has vastly improved because of eCHIRPP. Its online,* dynamic nature enables data entry in near real-time at the CHIRPP hospitals, compared to historically, when this was centralized at national headquarters. PHAC coders then verify the data, code patients’ narratives, complete data quality inspections and error handling, all online. This online, collaborative process allows considerably more data to be simultaneously entered into the system and is gradually decreasing lag time between data entry and information dissemination, resulting in near real-time injury information being available for analysis locally and nationally within a few days of patients presenting to the emergency room. (With the previous system of centralizing data entry at national headquarters, the lag time between data collection and data entry was up to two years given a data entry backlog that had accumulated.)

eCHIRPP also has integrated data management tools that have greatly enhanced its flexibility and timeliness. For instance, authorized CHIRPP staff can directly manipulate eCHIRPP’s linked codebook to periodically add new data elements (for example, a code for a new consumer product), and the rationale and history of changes are also automatically logged directly in eCHIRPP. These features greatly simplify and enhance autonomy over change management, ensure that historical documentation of the CHIRPP codebook is consistent and up-to-date and enable more timely capture and analysis of new issues and trends as the injury landscape evolves. Before CHIRPP became electronic, these tasks required separate and time-consuming manual change procedures and documentation and relied on technical services personnel to manipulate data elements in the CHIRPP database. Now CHIRPP staff can make these changes and update their documentation instantaneously in eCHIRPP.

The CHIRPP sites (see Table 1) now have greater autonomy over their information: they can extract eCHIRPP data and produce statistical reports using integrated eCHIRPP data analysis and query tools, making them less reliant on national headquarters to provide data extracts and conduct analyses. In a recent poll, 82% (9 out of 11; two “undecided”) of the CHIRPP sites that responded agreed/strongly agreed that they are now better equipped to efficiently respond to local information requests from media, researchers and others with an interest in injury statistics, as well as advance their own injury prevention, surveillance and research initiatives such as scientific studies and public awareness campaigns about injury prevention.

An integrated collaboration centre provides survey tools, documents management, and discussion and news forums that are simplifying access and sharing of injury surveillance knowledge across the CHIRPP network. The system also includes an integrated print management tool that allows each eCHIRPP site to print blank Injury/Poisoning Reporting forms, eliminating the need to ship forms, and the eCHIRPP dashboard also displays dynamic data entry and coding productivity statistics.

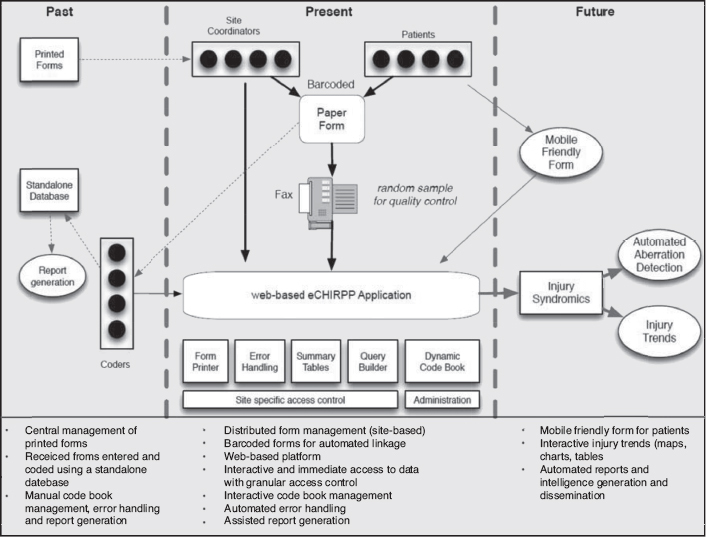

Figure 1 illustrates the CHIRPP process flow now and in the past, as well as how it is envisaged for the future.

FIGURE 1: The evolution of CHIRPP: from manual data collection to innovative insights.

Future directions

Timely information is critical for syndromic surveillance, the early identification of emerging hazards and changes in trends. Syndromic surveillance is “… the process of collecting, analysing and interpreting health-related data to provide an early warning of human or veterinary public health threats, which require public health action.”30,p.1 Pilot testing of CNPHI’s automated data monitoring and trend analysis tools—designed to monitor and flag incoming data according to predefined criteria and thresholds (for example, a new consumer product, or a rare but serious hazard)—is showing eCHIRPP’s potential for injury syndromics surveillance. In the case of rare events, a single case will generate a verifiable alert. An example of this are eye injuries caused by hockey sticks in organized minor hockey. No cases are expected because of the requirement to wear a full face shield and any generated alerts are likely to be false positives; so far, three false positives have been detected by eCHIRPP.

Syndromics surveillance was also applied to eCHIRPP data in a proof-of-concept study to analyze the effectiveness of monitoring and predicting laundry detergent packet-related injuries in Canada.31

Current and historical CHIRPP statistics are also provided to government and non-governmental organizations, media, academia and other stakeholders for injury prevention initiatives, and eCHIRPP has improved the timeliness of this information. Examples of injury topics that have recently been analyzed in response to such information requests include team sports, window and balcony falls, concussions, and hoverboard use statistics from the years 2015 and 2016, rather than pre-eCHIRPP statistics that were up to two years old. It was also possible to efficiently update CHIRPP sports injury statistics from 2004 to 201432 with estimates for 2015, in response to stakeholders’ requests for the most current information.

Future directions also include piloting a mobile-friendly version of eCHIRPP to collect data using hand-held devices, exploring the feasibility of integrated knowledge sharing across other CNPHI surveillance platforms, continuing assessment of applying injury syndromics for early detection of changes in trends and emerging issues, estimating denominators to calculate population rates, enhancing capture of intentional injuries, and increasing adult data collection by expanding to more general hospitals. Moreover, the interest in using eCHIRPP to enhance injury surveillance in the North is strong, which would provide a valuable opportunity to assess the unique circumstances and injury patterns of northern injuries.33

Limitations

Like all injury surveillance systems, the CHIRPP is not without limitations. As the program comprises a sample of Canada’s hospital EDs, the data should not be used to draw conclusions about injury patterns across the entire Canadian population. However, some studies, have shown CHIRPP data to be a representative of the profile of injuries in sports and recreation in Calgary, compared to regional health administrative data; 34,35 injury cases at Montreal Children’s Hospital that did not require admission, did not present to the ED overnight, or were not poisonings;21 and children with severe injuries and younger children presenting at the Children’s Hospital of Ontario.36

Because most of the CHIRPP hospitals are pediatric (usually located in major cities), certain groups are under-represented in the data, including rural inhabitants (including some Aboriginal peoples), older teens and adults. Also, while CHIRPP captures people who are dead-on-arrival at the hospital, those who died at the scene or later in hospital are not included. Patients who bypass the ED registration desk for immediate treatment may not be captured as well as those who do not complete an Injury/Poisoning Reporting form. On average, the CHIRPP capture rate (percentage of eligible patients who complete a CHIRPP form) is 68%, and is even as high as 90% to 100% at some hospitals.

The process of establishing the new eCHIRPP system itself also had various limitations. Additional time and effort was invested by CHIRPP personnel at national headquarters and the hospital sites to develop eCHIRPP training materials and protocols, undergo training and hospitals’ ethics review, and the sites also had to adapt to the increased workload of performing data entry. Network delays at the sites have also occurred periodically, and as with any system, brief, periodic service interruptions are required when system updates are performed.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to the knowledge on modernizing injury surveillance systems.

It demonstrates the CHIRPP’s flexibility, showcasing recent years. Changes to the codebook reflect evolving information demands, and eCHIRPP’s implementation has enabled the program to make great strides in enhancing its dynamic and flexible nature, while improving the timeliness of its information. The eCHIRPP system is also in keeping with the Government of Canada’s modernization agenda, and new knowledge about injuries and their protective and risk factors will also continue to influence the CHIRPP’s evolution as health surveillance must continue to adapt to changes in the populations being monitored, new knowledge and technology, and changing information demands.

Acknowledgements

The dedication of the following individuals and organizations to the CHIRPP is deeply appreciated: James Cheesman, Nicole Courville, Fernande Dupuis, Margaret Herbert, Joy Laham, Patrick McGuire, Joan McGuire-Slade, Brynn McLennan, Melinda Tiv and Brian Wray. Past and present CHIRPP directors and co-ordinators at the following sites are also acknowledged: BC Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, B.C.; Kelowna General Hospital, Kelowna, B.C.; Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Alta.; Stollery Children’s Hospital, Edmonton, Alta.; Winnipeg Children’s Hospital, Winnipeg, Man.; Arctic Bay Health Centre, Arctic Bay, Nun.; Children’s Hospital at London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ont.; The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ont.; Kingston General Hospital, Kingston, Ont.; Hotel Dieu Hospital, Kingston, Ont.; Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ont.; Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montréal, Que.; CHU Ste. Justine Mother and Children University Hospital Centre, Montréal, Que.; Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus du CHU de Québec, Québec, Que.; IWK Health Centre, Halifax, N.S.; Janeway Children’s Health and Rehabilitation Centre, St. John’s, N.L.; Carbonear General Hospital, Carbonear, N.L.; and the Newfoundland Centre for Health Information, St. John’s, N.L.

Footnotes

Access to the eCHIRPP platform is restricted to users whose registration is vetted and approved by the Public Health Agency of Canada and participating hospitals, and the sign-on in process is secure and password-protected.

References

- 1.Statistics Canada. Table 102-0561. Leading causes of death, total population, by age group and sex, Canada, annual [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; [cited 2016 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang = eng&id = 1020561. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parachute . The Cost of Injury in Canada. Toronto (ON): Parachute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holder Y, Peden M, Krug E, Lund J, Gururaj G, Kobusingye O., editors. Injury surveillance guidelines. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2001.. Joint publication of the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naylor D, editor. Learning from SARS: renewal of public health in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2003. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CSA Group . Children’s playspaces and equipment. Catalogue number CAN/CSA-Z614-14. Toronto (ON): Canadian Standards Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Canada . Injury data analysis leads to baby walker ban [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; [modified 2007 Oct 10; cited 2014 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/sr-sr/activ/consprod/baby-bebe-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 7.ATV youth injuries down, Halifax MD says [Internet] HaliCBC News Nova Scotia; 2011 Aug 8 [cited 2014 Jan 28] Available from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/atv-youth-injuries-down-halifax-md-says-1.1007280. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Off-highway vehicles act. R.S., c. 323, s. 1 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackenzie SG. Injuries associated with hooks in retail displays. Chronic Dis Can. 1992;13(6):116–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forward KE, Seabrook JA, Lynch T, Lim R, Poonai N, Sangha GS. A comparison of the epidemiology of ice hockey injuries between male and female youth in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19((8)):418–22. doi: 10.1093/pch/19.8.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsay H, Brussoni M. Injuries and helmet use related to non-motorized wheeled activities in paediatric patients. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34:74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keays G, Dumas A. Longboard and skateboard injuries. Injury. 2014;45((8)):1215–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.03.010. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherniawsky H, Bratu I, Rankin T, Sevcik WB. Serious impact of handlebar injuries. Clin Pediatr. 2014;53((7)):672–76. doi: 10.1177/0009922814526977. doi: 10.1177/0009922814526977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickett W, Kukaswadia A, Thompson W, et al. Use of diagnostic imaging in the emergency department for cervical spine injuries in Kingston, Ontario. CJEM. 2014;16((1)):25–33. doi: 10.2310/8000.2013.131051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanlaar W, McAteer H, Brown S, Crain J, McFaull S, Hing MM. Injuries related to off-road vehicles in Canada. Accident Anal Prev. 2015;75:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2014.12.006. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fridman L, Fraser-Thomas JL, McFaull S, MacPherson A. Epidemiology of sports-related injuries in children and youth presenting to Canadian emergency departments from 2007–2010. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2013;5:30. doi: 10.1186/2052-1847-5-30. doi: 10.1186/2052-1847-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) [Internet] Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control; c. 2012 [cited 2015 February 26]. Available from http://www.cpsc.gov/en/Safety-Education/Safety-Guides/General-Information/National-Electronic-Injury-Surveillance-System-NEISS/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Injury database [Internet] Brussels: European Commission; c. 2015 [cited 2015 March 4] Available from http://ec.europa.eu/health/data_collection/databases/idb/index_en.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang K, Wang J, Mikami Y. Evaluations on several national injury surveillance systems. Appl Mech Mater. 2013;321-324:2596–601. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackenzie SG, Pless IB. CHIRPP: Canada’s principal injury surveillance program. Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program. Inj Prev. 1999;5:208–13. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macarthur C, Pless IB. Evaluation of the quality of an injury surveillance system. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149((6)):586–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbert M, Mackenzie SG. Injury surveillance in paediatric hospitals: the Canadian experience. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9((5)):306–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Government of Canada. Blueprint 2020: Getting started – getting your views. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkwood G, Hughes TC, Pollock AM. Injury surveillance in Europe and the UK. BMJ. 2014;349:g5337. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5337. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClure RJ, Mack K. Injury surveillance as a distributed system of systems. Inj Prev. 2015;0:1–2. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041788. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . International classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mukhi S, Aramini J, Kabani A. Contributing to communicable diseases intelligence management in Canada: CACMID meeting, March 2007, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2007;18((6)):353–56. doi: 10.1155/2007/386481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukhi SN, Chester TL, Klaver-Kibria JD, et al. Innovative technology for web-based data management during an outbreak. Online J Public Health Inform. 2011;3((1)):1–13. doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v3i1.3514. doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v3i1.3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukhi SN, Meghnath K, Kuschak TI, Chu M, Ng LK. A web-based system for mapping laboratory networks: analysis of GLaDMap application. Online J Public Health Inform. 2012;4((2)):1–11. doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v4i2.4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syndromic surveillance . . London (UK): Public Health England; systems and analyses [Internet] [cited 2015 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/syndromic-surveillance-systems-and-analyses. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Do MT, Cheesman J. Injury ‘syndromics’: a proof-of-concept using detergent packets. Inj Prev. 2015;21(Suppl 2):A1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McFaull S, Subaskaran J, Branchard B, Thompson W. Emergency department surveillance of injuries and head injuries associated with baseball, football, soccer and ice hockey, children and youth, ages 5 to 18 years, 2004 to 2014. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36((1)):13–4. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.1.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Do MT, Fréchette M, McFaull S, Denning B, Ruta M, Thompson W. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013. Injuries in the North – analysis of 20 years of surveillance data collected by the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program. p. 72. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickett W, Brison RJ, Mackenzie SG, Garner M, King MA, Greenberg TL, et al. Youth injury data in the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program: do they represent the Canadian experience? Inj Prev. 2000;6((1)):9–15. doi: 10.1136/ip.6.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang J, Hagel B, Emery CA, Senger T, Meeuwisse W. Assessing the representativeness of Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Programme (CHIRPP) sport and recreational injury data in Calgary, Canada. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2013;20((1)):19–26. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.656315. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.656315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macpherson AK, White HL, Mongeon S, Grant VJ, Osmond M, Lipskie T, et al. Examining the sensitivity of an injury surveillance program using population-based estimates. Inj Prev. 2008;14:262–5. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.018374. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.018374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]