Abstract

Introduction:

Given the proposed changes to nutrition labelling in Canada and the dearth of research examining comprehension and use of nutrition facts tables (NFts) by adolescents and young adults, our objective was to experimentally test the efficacy of modifications to NFts on young Canadians’ ability to interpret, compare and mathematically manipulate nutrition information in NFts on prepackaged food.

Methods:

An online survey was conducted among 2010 Canadians aged 16 to 24 years drawn from a consumer sample. Participants were randomized to view two NFts according to one of six experimental conditions, using a between-groups 2×3 factorial design: serving size (current NFt vs. standardized serving-sizes across similar products) × percent daily value (% DV) (current NFt vs. “low/med/high” descriptors vs. colour coding). The survey included seven performance tasks requiring participants to interpret, compare and mathematically manipulate nutrition information on NFts. Separate modified Poisson regression models were conducted for each of the three outcomes.

Results:

The ability to compare two similar products was significantly enhanced in NFt conditions that included standardized serving-sizes (p ≤ .001 for all). Adding descriptors or colour coding of % DV next to calories and nutrients on NFts significantly improved participants’ ability to correctly interpret % DV information (p ≤ .001 for all). Providing both standardized serving-sizes and descriptors of % DV had a modest effect on participants’ ability to mathematically manipulate nutrition information to calculate the nutrient content of multiple servings of a product (relative ratio = 1.19; 95% confidence limit: 1.04–1.37).

Conclusion:

Standardizing serving-sizes and adding interpretive % DV information on NFts improved young Canadians’ comprehension and use of nutrition information. Some caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to all Canadian youth due to the sampling issues associated with the study population. Further research is needed to replicate this study in a more heterogeneous sample in Canada and across a range of food products and categories.

Keywords: adolescents, young adults, nutrition policy, food labelling

Key findings

Our study provides preliminary evidence, the first in Canada, supporting the efficacy of modifications to the nutrition facts table (NFt) on consumer understanding and use of nutrition information.

Results suggest that both standardizing serving-sizes and providing descriptors or colour coding to interpret percent daily values (% DVs) on NFts help young Canadians interpret, compare and mathematically manipulate nutrition information. Some caution should be exercised to generalize these findings to all Canadian youth due to sampling issues associated with the study population.

These findings can be used to support an ongoing review of proposed changes to the NFt.

Introduction

Poor diet is a leading risk factor for chronic disease and premature death in Canada.1 A higher intake of calories, saturated fat and sodium is linked to a greater risk of obesity, diabetes mellitus and heart disease.2-4 The development of nutrition-related conditions, such as obesity and diabetes, is increasingly evident in adolescents and young adults in Canada and internationally.5-8 Adolescence and young adulthood are dynamic stages of human development associated with increasing independence, a growing role in food shopping and preparation, and the development of long-term eating patterns that can remain relatively stable throughout life.9-11 Population-based nutrition interventions should aim to support the development of healthy eating habits among young people in Canada.

Providing clear and accurate nutrition information is one way to support healthier and more informed food choices. Mandatory nutrition labelling on prepackaged food was implemented in Canada in 2005 so that consumers can compare the nutritional value of foods and make informed choices.12 This legislation requires the nutrition facts table (NFt) to be displayed on most prepackaged foods. The NFt provides information about the number of calories and the quantities of 13 nutrients per serving as well as the percentage of these amounts in terms of nutrient recommendations for a 2000-calorie adult diet (daily value [% DV]).

NFts are the most common source of nutrition information in Canada: more Canadians report using nutrition information from food labels on prepackaged foods than from any other source, including the Internet, dietitians and mass media.13 Moreover, Canadian consumers prefer the NFt over other front-of-package nutrition labelling systems with respect to liking, helpfulness, credibility and influence on purchase decisions.14 This is consistent with a large body of evidence from a number of countries that demonstrates that mandatory food labels have a broad reach and are sustainable and credible as a health education tool.15

Despite their widespread use, recent research has exposed several limitations in Canadian adults’ comprehension and use of NFts.16 First, although the majority of Canadian adults indicate that NFt information is important, they find comparing nutrition information across similar foods to be difficult when serving sizes on NFts are not the same. While the Canadian Food Inspection Agency outlines product-specific ranges for a serving size, food manufacturers ultimately determine the serving size displayed on NFts.17 Since nutrient disclosures on NFts are based on serving size, consistent use of sizes could help compare the nutrient content of similar foods.

Moreover, most Canadian adults are unable to understand or use % DV listed on NFts.16 Listing the % DV on NFts is intended to simplify comparisons across foods and assist consumers in determining whether a food has a little or a lot of a nutrient.18 However, almost one-third of Canadian adults do not understand that the % DV can help them compare foods, and 74% are unable to interpret the % DV on NFts to determine if a food is high or low in a nutrient.16 Research suggests that enhancing % DV information on NFts with simple descriptors (“low,” “medium” or “high”) and/or colour may enhance comprehension and, as a result, the use of nutrition information.15,19 Such interpretational formats to present nutrition information is also well supported in examinations of front-of-package food-labelling systems.20

To our knowledge, not a single published study in Canada has examined adolescents’ and young adults’ comprehension and use of NFts on prepackaged food. The few studies conducted among adolescents internationally suggest that understanding and use of nutrition labels within this group is low.19,21 Nutrition labelling regulations are currently under review in Canada, providing the opportunity to develop labelling requirements that better support healthier food choices.22 The objective of our study was to experimentally test the efficacy of modified NFts with the current NFt in terms of comprehension and use of nutrition information by adolescents and young adults. The NFt modifications tested included standardized serving-sizes, and the addition of interpretive information (i.e. simple descriptors or colour coding) to % DV values. These modifications were selected because unequal serving-sizes and challenges in interpreting the % DV have been identified as important barriers to comprehension and use of NFts among Canadian adults.16 Specifically, we examined the impact of these NFt modifications on participants’ ability to interpret, compare and mathematically manipulate nutrition information on prepackaged food.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

An online survey of 2010 participants aged 16 to 24 years from across Canada was conducted in August 2014. Participants were recruited from an established national online consumer panel provided by Nielsen, a market research company (Nielsen: http://www.nielsen.com/ca/en.html). The panel was recruited through online advertisements and social media, targeted emails, online co-registration offers and telephone recruitment. For this study, a stratified random sample of Nielsen panellists of eligible age was sent an email invitation to complete the survey. An equal number of males and females, and an equal number of adolescents (16 to 18 years) and young adults (19 to 24 years) were recruited. Participants residing in the territories were excluded from the sampling frame.

Upon completion of the survey, participants were paid approximately $2.00 to $3.00. Surveys were in English only, and participant consent was obtained.

Ethical approval for the study was received from the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Waterloo.

Study design

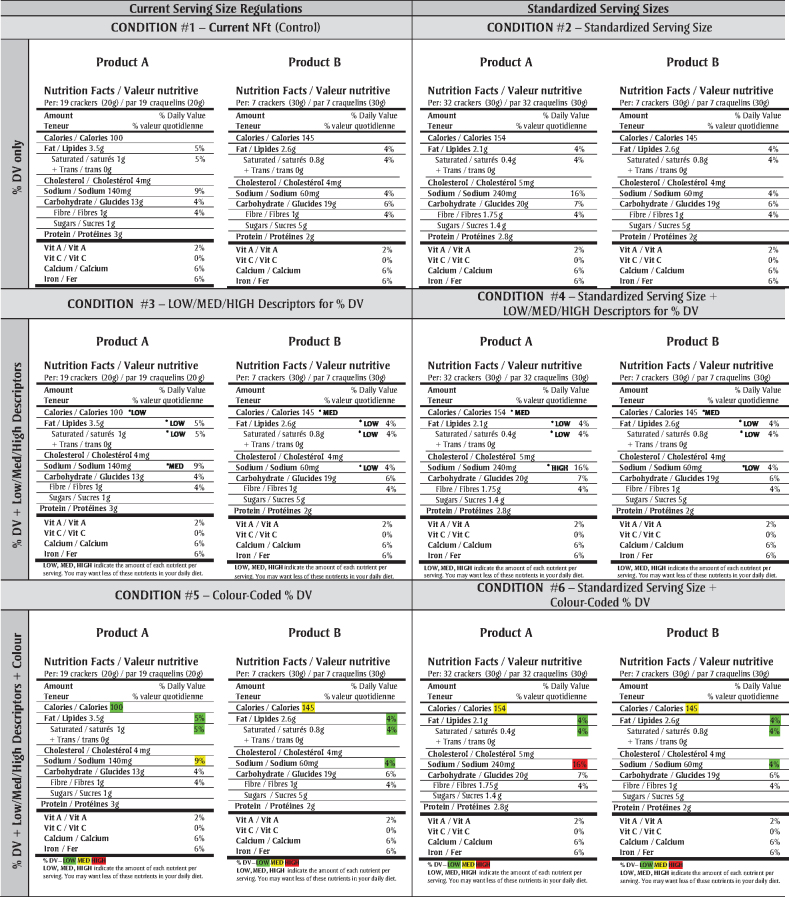

We used a between-groups experimental design to test comprehension and use of modified formats of the NFt compared to the current NFt in Canada. Participants were randomly assigned to simultaneously view images of two fictitious brands of crackers displaying an NFt systematically altered according to one of six labelling conditions (Figure 1). The labelling conditions were based on a 2 × 3 factorial design: serving size (current NFt vs. standardized serving-sizes across similar products) × % DV information (current NFt vs. “low”/“medium”/“high” descriptors vs. colour coding). Standardized serving-sizes were selected based on recommendations in Canada’s Food Guide. Criteria for categorizing % DV were consistent with Health Canada’s online educational materials,18 where 5% DV or less of a nutrient is marked “low” or green, 6% to 14% DV of a nutrient is marked “medium” or yellow and 15% DV or more of a nutrient is marked “high” or red. While standardization of serving sizes affects all nutrients shown on the NFt, the additional interpretive aids (simple descriptors or colour coding) were applied to calories and negative nutrients only (i.e. total fat, saturated fat and sodium) as consumers consult NFts for negative nutrients more frequently than for positive nutrients,23 and stronger evidence supports associations between negative nutrients and increased risk for disease.20

FIGURE 1. Six nutrition facts table conditions.

The nutritional values displayed on the NFts were similar to those on commercial cracker brands, but were manipulated so that one option was high (≥ 15% DV) or moderate (6%–14% DV) and one option was low (≤ 5% DV) in sodium per serving, based on the adequate intake level of 1500 mg/day.24 The sodium levels in the six conditions were counterbalanced so that for half of the participants, the first cracker box was the low sodium option and for the other half, the second box was the low sodium option.

Crackers were used for this study because they are a widely consumed snack with broad appeal and because their nutritional quality is perceived as neither extremely healthy nor unhealthy. The NFts were displayed on images of actual cracker boxes using fictional brand names, with a consistent product weight of 225 g. The cracker boxes appeared onscreen as two-dimensional images with views of the side and front of the package to enable participants to view product information including brand, product weight and the NFt. The boxes remained onscreen until the survey items were completed.

Survey measures

Sociodemographics and nutrition-related behaviours

We assessed sociodemographic variables, including gender, age, region, education level (recoded as “high school or less,” “college or some university” or “university degree or higher”), employment status and ethnicity. In addition, we asked participants to rate their diet quality and indicate their weight goals and food shopping and preparation responsibilities.

We assessed participants’ weight goals by asking “Which of the following are you trying to do about your weight: lose weight, gain weight, stay the same weight, and not trying to do anything about your weight?” This question was adapted from a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) measure that asked participants if they would like to weigh more or less or stay the same.25

We examined food shopping and preparation responsibilities using the question, “Which one of the following statements most accurately reflects your role in your household?” The response options were “I am the person who is most responsible for grocery shopping,” “I am the person who is most responsible for meal preparation,” “I am the person who is most responsible for both grocery shopping and meal preparation” and “I am not primarily responsible for either grocery shopping or meal preparation.”

Finally, similar to previous studies, we assessed participants’ knowledge of recommended calorie intake by asking, “On average, how many calories should a healthy, moderately active adult [male/female] consume each day to maintain a healthy weight?”26-28 Numeric responses (limited to between 0 and 100 000) were coded as correct if the response fell within the range of 1500 to 3000 calories per day (based on Health Canada recommendations for daily energy requirements among young adults for varying levels of physical activity29).

Outcome measures

We used an online survey to assess participants’ ability to interpret, compare and mathematically manipulate nutrition information on NFts. The survey included seven performance tasks that required understanding and use of the NFt information listed on food products. The seven performance tasks were developed based on a tool used in a Health Canada–commissioned study16 and research by Mackison et al.,30 who tested the validity and reliability of tasks measuring consumer understanding, use and perceptions of nutrition labels.

Interpreting % DV information on NFts

Two performance tasks assessed participants’ ability to interpret % DV information. First, participants were shown one cracker box and asked: “Does this product contain a lot of sodium, a moderate amount of sodium, or a little sodium?” Next, participants were asked: “Looking at this box, is the amount of total fat per serving in this product high, a moderate amount, or low?”

Comparing information between two NFts

Three performance tasks assessed participants’ ability to compare nutrition information between two NFts. First, we asked participants: “Looking at Products A and B, which product do you think would be the best option for someone trying to reduce their risk of high blood pressure by lowering their sodium intake?” Next, we asked: “Looking at Products A and B, which product do you think would be the best option for someone trying to eat fewer calories?” Finally, participants were asked: “Looking at both Product A and Product B, how do they compare in terms of their sodium content?” Response options were “a lot in both,” “a little in both,” “Product A has a little and Product B has a lot,” “Product A has a lot and Product B has a little,” “Product A has a little and Product B has a moderate amount” and “Product A has a moderate amount and Product B has a little.”

Mathematically manipulating nutrition information on NFts

We used two performance tasks to examine participants’ ability to mathematically manipulate nutrition information on NFts. First, participants were asked: “If you consumed one-half of this box, what percentage of your recommended % Daily Value of total fat would you consume?” Next, participants were asked: “How many servings of this product would you have to eat in order to get all of the fibre you need in one day?”

Data analysis

We used chi-square tests to examine differences in participant characteristics between NFt conditions, and differences in the proportion of participants who correctly responded to the survey items for each of the seven performance tasks across the NFt conditions. Next, we conducted separate modified Poisson regression models using combined scores for tasks related to each of the three outcomes: interpret (2 items), compare (3 items), and mathematically manipulate (2 items) to assess the number of correct responses for each NFt condition compared to the control condition. We examined associations between covariates of interest (education, ethnicity, employment status, region, weight goal, food shopping and preparation responsibilities, knowledge of calorie recommendations, and perceived diet quality) and each of the three outcomes in models that included the main effect (condition) and adjusted these for age and gender. Covariates with a p value less than .2 or that altered the beta coefficient of the main effect by more than 20%, were included in the final model. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC, US).

Results

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences (p < .05) were observed across NFt conditions for sociodemographic and most nutrition-related behaviours, with the exception of knowledge of calorie recommendations, indicating successful randomization.

TABLE 1. Distribution of participant characteristics by nutrition facts table conditions.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 2010) | Current NFt (control) (n = 336) | Standardized serving-size (n = 335) | Low/medium/high descriptors for % DV (n = 336) | Standardized serving-size + low/medium/high descriptors for % DV (n = 334) | Colour-coded % DV (n = 335) | Standardized serving-size + colour-coded % DV (n = 334) | Chi-square | p value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | |||

| Age, years | ||||||||||||||||

| 16–18 | 50.0 | (1004) | 53.9 | (181) | 49.0 | (164) | 52.7 | (177) | 46.7 | (156) | 49.9 | (168) | 48.2 | (161) | 5.0 | .42 |

| 19–24 | 50.1 | (1006) | 46.1 | (155) | 51.0 | (171) | 47.3 | (159) | 53.3 | (178) | 50.2 | (167) | 51.8 | (173) | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | 50.2 | (1008) | 43.5 | (146) | 52.2 | (175) | 50.3 | (169) | 52.4 | (175) | 52.2 | (175) | 50.3 | (168) | 7.9 | .16 |

| Male | 49.9 | (1002) | 56.6 | (190) | 47.8 | (160) | 49.7 | (167) | 47.6 | (159) | 47.8 | (160) | 49.7 | (166) | ||

| Education level | ||||||||||||||||

| Low (high school or less) | 56.7 | (1139) | 54.8 | (184) | 56.7 | (190) | 56.9 | (191) | 58.7 | (196) | 56.4 | (189) | 56.6 | (189) | 2.3 | .99 |

| Medium (college or some university) | 31.0 | (624) | 32.4 | (109) | 31.0 | (104) | 29.8 | (100) | 29.3 | (98) | 32.5 | (109) | 31.1 | (104) | ||

| High (university degree or higher) | 12.3 | (247) | 12.8 | (43) | 12.2 | (41) | 13.4 | (45) | 12.0 | (40) | 11.0 | (37) | 12.3 | (41) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| White | 58.4 | (1174) | 55.4 | (186) | 59.4 | (199) | 59.5 | (200) | 57.2 | (191) | 57.3 | (192) | 61.7 | (206) | 3.4 | .63 |

| Other | 41.6 | (836) | 44.6 | (150) | 40.6 | (136) | 40.5 | (136) | 42.8 | (143) | 42.7 | (143) | 38.3 | (128) | ||

| Region | ||||||||||||||||

| Atlantic | 8.8 | (173) | 8.2 | (27) | 11.6 | (38) | 10.3 | (34) | 7.3 | (24) | 7.3 | (24) | 7.9 | (26) | 19.8 | .18 |

| Western | 42.5 | (838) | 43.8 | (144) | 45.3 | (148) | 41.5 | (137) | 43.2 | (142) | 38.5 | (127) | 42.6 | (140) | ||

| Ontario | 42.5 | (839) | 40.1 | (132) | 37.0 | (121) | 43.6 | (144) | 44.1 | (145) | 45.5 | (150) | 44.7 | (147) | ||

| Quebec | 6.3 | (124) | 7.9 | (26) | 6.1 | (20) | 4.6 | (15) | 5.5 | (18) | 8.8 | (29) | 4.9 | (16) | ||

| Employment | ||||||||||||||||

| Full-time | 24.1 | (474) | 22.3 | (73) | 24.8 | (81) | 22.5 | (74) | 25.6 | (84) | 23.2 | (76) | 26.4 | (86) | 16.8 | .67 |

| Part-time | 32.9 | (646) | 31.2 | (102) | 34.3 | (112) | 33.7 | (111) | 30.2 | (99) | 33.3 | (109) | 34.7 | (113) | ||

| Unemployed (looking for work) | 13.2 | (260) | 13.5 | (44) | 10.7 | (35) | 14.3 | (47) | 14.6 | (48) | 14.4 | (47) | 12.0 | (39) | ||

| Unemployed (not looking, includes full-time students) | 28.5 | (559) | 30.6 | (100) | 28.1 | (92) | 28.6 | (94) | 29.3 | (96) | 28.1 | (92) | 26.1 | (85) | ||

| Unable to work | 1.3 | (25) | 2.5 | (8) | 2.1 | (7) | 0.91 | (3) | 0.3 | (1) | 0.92 | (3) | 0.92 | (3) | ||

| Food shopping and meal preparation responsibilities in household | ||||||||||||||||

| Most responsible for food shopping in household | 6.4 | (126) | 5.8 | (19) | 6.4 | (21) | 5.4 | (18) | 7.9 | (26) | 6.4 | (21) | 6.5 | (21) | 19.2 | .20 |

| Most responsible for meal preparation in household | 7.4 | (145) | 4.6 | (15) | 8.5 | (21) | 8.8 | (29) | 7.6 | (25) | 8.2 | (27) | 6.5 | (21) | ||

| Most responsible for both food shopping and meal preparation in household | 16.2 | (320) | 20.5 | (67) | 17.3 | (57) | 18.1 | (60) | 12.2 | (40) | 16.4 | (54) | 12.9 | (42) | ||

| Not responsible for either | 70.0 | (1379) | 69.1 | (226) | 67.8 | (223) | 67.7 | (224) | 72.3 | (238) | 69 | (227) | 74.2 | (241) | ||

| Knowledge of calorie recommendations | ||||||||||||||||

| Correct understanding of recommended calorie intake | 60.0 | (1194) | 60.2 | (200) | 62.4 | (206) | 63.8 | (213) | 51.7 | (171) | 60.0 | (197) | 62.7 | (207) | 13.5 | .02 |

| Incorrect understanding of recommended calorie intake | 40.0 | (797) | 39.8 | (132) | 37.6 | (124) | 36.2 | (121) | 48.3 | (160) | 41.0 | (137) | 37.3 | (123) | ||

| Self-reported diet quality | ||||||||||||||||

| Fair or poor | 38.1 | (766) | 38.7 | (130) | 36.4 | (122) | 39.6 | (133) | 40.4 | (135) | 36.1 | (121) | 37.4 | (125) | 3.6 | .97 |

| Good | 34.9 | (702) | 34.8 | (117) | 35.8 | (120) | 35.1 | (118) | 31.4 | (105) | 36.4 | (122) | 35.9 | (120) | ||

| Excellent or very good | 27.0 | (542) | 26.5 | (89) | 27.8 | (93) | 25.3 | (85) | 28.1 | (94) | 27.5 | (92) | 26.7 | (89) | ||

| Personal Weight Goal | ||||||||||||||||

| To gain weight | 15.6 | (310) | 16.6 | (55) | 15.2 | (50) | 12.4 | (41) | 12.7 | (42) | 17.4 | (58) | 19.6 | (64) | 22.2 | .10 |

| To lose weight | 40.3 | (799) | 35.1 | (116) | 40.0 | (132) | 42.2 | (140) | 43.7 | (145) | 43.8 | (146) | 36.7 | (120) | ||

| To maintain weight | 23.5 | (467) | 23.3 | (77) | 25.8 | (85) | 24.7 | (82) | 21.7 | (72) | 22.2 | (74) | 23.6 | (77) | ||

| Not trying to do anything about weight | 20.6 | (409) | 25.1 | (83) | 19.1 | (63) | 20.8 | (69) | 22.0 | (73) | 16.5 | (55) | 20.2 | (66) | ||

Abbreviations: NFt, nutrition facts table; % DV, percent daily value.

Notes: Totals may not sum to final sample size, reflecting missing values for some respondents. In each case, missing values represent < 3% of the total sample. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Interpreting % DV information on NFts

In the first of two interpretation tasks, significantly more participants accurately interpreted sodium information in four modified NFt conditions (low/medium/high descriptors, standardized serving-size+ low/medium/high descriptors, colour-coded % DV information, standardized serving-size + colour-coded % DV; p < .005 for all) compared to the control condition (Table 2). Correctly interpreting total fat information was more likely in all five modified NFt conditions compared to the control condition (p ≤ .001 for all; Table 2).

TABLE 2. Distribution of participant characteristics by nutrition facts table conditions (N = 2010).

| Current NFt (control) (n = 336) | Standardized serving-size (n = 335) | Low/medium/high descriptors for % DV (n = 336) | Standardized serving-size + low/medium/high descriptors for % DV (n = 334) | Colour-coded % DV (n = 335) | Standardized serving-size + colour-coded % DV (n = 334) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | p | % | n | p | % | n | p | % | n | p | % | n | p | |

| Interpret | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Does this product contain: a lot, a moderate amount, or a little sodium? | 43.8 | (147) | 37.6 | (126) | .11 | 57.7 | (194) | < .001 | 68 | (227) | < .001 | 55.5 | (186) | .002 | 54.8 | (183) | .004 |

| 2. Is the amount of total fat per serving in this product high, a moderate amount, or low? | 34.2 | (115) | 47.5 | (159) | < .001 | 72.0 | (242) | < .001 | 70.4 | (235) | < .001 | 67.5 | (226) | < .001 | 71.0 | (237) | < .001 |

| Compare | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Which product is the best option for someone who is trying to reduce their risk of high blood pressure by lowering sodium intake? | 63.7 | (214) | 68.4 | (229) | .20 | 79.8 | (268) | < .001 | 72.2 | (241) | .02 | 74.3 | (249) | .003 | 76.7 | (256) | < .001 |

| 2. Which product is the best option for someone trying to eat fewer calories? | 25.0 | (84) | 54.6 | (183) | < .001 | 21.4 | (72) | .27 | 56.6 | (189) | < .001 | 24.2 | (81) | .81 | 57.2 | (191) | < .001 |

| 3. How do these two products compare for sodium? | 28.0 | (94) | 39.7 | (133) | .001 | 19.1 | (64) | .006 | 57.8 | (193) | < .001 | 23.6 | (79) | .19 | 57.8 | (193) | < .001 |

| Mathematically manipulate | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. If you consumed one-half of this box, what % DV total fat would you consume? | 10.4 | (35) | 18.5 | (62) | .003 | 9.8 | (33) | .80 | 19.2 | (64) | .001 | 9.9 | (33) | .81 | 16.8 | (56) | .02 |

| 2. How many servings would you have to eat to get all the fibre you need in a day? | 56.6 | (190) | 56.1 | (188) | .91 | 60.7 | (204) | .27 | 57.5 | (192) | .81 | 57.3 | (192) | .84 | 59.9 | (200) | .38 |

Abbreviations: NFt, nutrition facts table; % DV, percent daily value.

Note: Chi-square tests were used to determine significant differences in correct responses between each NFt condition and the control.

As shown in Table 3, the adjusted modified Poisson regression model indicates that participants exposed to NFt conditions with low/medium/high descriptors (relative ratio [RR] = 1.67; 95% CL: 1.48–1.89), standardized serving-size + low/medium/high descriptors (RR = 1.80; 95% CL: 1.60–2.03), colour-coded % DV information (RR = 1.61; 95% CL: 1.42–1.82), and standardized serving-sizes + colour-coded % DV information (RR = 1.63; 95% CL: 1.44–1.84) were significantly more likely to correctly interpret NFt information compared to the control condition. In contrast, the NFt condition with standardized serving-sizes only did not significantly improve participants’ ability to correctly interpret NFt information (p=0.14; Table 3).

TABLE 3. Results of modified Poisson models assessing participants’ ability to interpret, compare and mathematically manipulate nutrition facts table information within each nutrition facts table condition compared to the current nutrition facts table (control condition).

| Standardized serving-size | Low/med/high descriptors for % DV | Standardized serving-size + low/med/high descriptors for % DV | Colour-coded % DV | Standardized serving-size + colour-coded % DV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CL) | RR (95% CL) | RR (95% CL) | RR (95% CL) | RR (95% CL) | |

| Interpreta | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) | 1.67 (1.48–1.89) | 1.80 (1.60–2.03) | 1.61 (1.42–1.82) | 1.63 (1.44–1.84) |

| Compareb | 1.41 (1.24–1.59) | 1.03 (0.92–1.15) | 1.60 (1.53–1.80) | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) | 1.64 (1.46–1.83) |

| Manipulatec | 1.14 (0.99–1.31) | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 1.19 (1.04–1.37) | 1.03 (0.90–1.18) | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) |

Abbreviations: % DV, % daily value; RR, relative ratio; 95% CL, 95% confidence limits.

Adjusted for age, gender, education level, ethnicity, region, weight goal, food shopping and preparation responsibilities, knowledge of calorie recommendations.

Adjusted for age, gender, employment, region, weight goal, food shopping and preparation responsibilities, perceived diet quality, knowledge of calorie recommendations.

Adjusted for age, gender, education level, employment, ethnicity, region, weight goal, food shopping and preparation responsibilities, perceived diet quality, knowledge of calorie recommendations.

Comparing information between two NFts

In the first of the three comparison tasks, significantly more participants were able to correctly compare two NFts and identify the product with lower sodium in all modified NFt conditions, with the exception of the condition modifying standardized serving-size only, as compared to the control condition (p ≤ .02 for all; Table 2).

For the second comparison task, comparing and correctly identifying the product with fewer calories was significantly higher for NFt conditions with standardized serving-size (p < .001), standardized serving-size + low/medium/high descriptors (p < .001) and standardized serving-size + colour-coded % DV information (p < .001 ).

Finally, in the third comparison task, correctly comparing sodium information between two products was significantly higher in three NFt conditions, standardized serving-size (p = .001), standardized serving-size + low/medium/high descriptors (p < .001) and standardized serving-size + colour-coded % DV information (p < .001) compared to the control condition. Correct comparison of sodium information was significantly lower when participants were exposed to low/med/high descriptors (p = .006).

In the adjusted modified Poisson regression model, significantly more participants in the NFt conditions with standardized serving-size (RR = 1.41; 95% CL: 1.24–1.59) and standardized serving-size in combination with low/medium/high descriptors (RR = 1.60; 95% CL: 1.53–1.80) or colour-coded % DV information (RR = 1.64; 95% CL: 1.46–1.83) were able to correctly compare between two NFts relative to participants in the control condition (Table 3).

Mathematically manipulating nutrition information on NFts

Participants’ ability to mathematically manipulate total fat information was low overall, falling below 20% across all conditions. However, accuracy was significantly higher for three NFt conditions (standardized serving-size, standardized serving-size + low/medium/high descriptors, standardized serving-size + colour-coded % DV information; p < .05 for all) compared to the control condition (Table 2). More than half of the participants were able to correctly mathematically manipulate fibre information across all five NFt conditions including the control condition; no overall effect by condition was detected (p = .79).

Results of the adjusted modified Poisson regression model indicate that the NFts with standardized serving-size plus low/medium/high descriptors had a modest but significant effect on participants’ ability to correctly mathematically manipulate nutrition information compared to the control NFt (RR = 1.19; 95% CL: 1.04–1.37; Table 3). No other labelling conditions significantly improved participants’ ability to mathematically manipulate NFt information.

Discussion

This is one of the first peer-reviewed studies in Canada to examine the effect of NFt modification on young people’s comprehension and use of nutrition information. It is also among the first empirical studies of NFts conducted among young people internationally.19,21 Our findings show that standardizing serving-size information and providing simple descriptors or colour coding to interpret % DV information on NFts improves adolescent and young adults’ ability to interpret, compare, and mathematically manipulate nutrition information.

Standardized serving-sizes on NFts strongly enhanced young peoples’ ability to compare two similar food products. Previous evidence suggests that inconsistencies in the serving sizes listed on NFts across products can bias perceptions and purchase intent in favour of the product with the smaller serving-size, which may not necessarily be the nutritionally superior product.31 Requiring manufacturers to use standardized serving-sizes across similar products may be a promising strategy for facilitating understanding and accurate use of nutrition information on food labels.

Adding descriptors or colour coding next to calories and nutrient amounts on NFts proved critical for young people to correctly interpret % DV information on products. These findings are consistent with results from expert reports and studies examining front-of-package food-labelling systems.32 Applying descriptors or colour coding gives consumers interpretational aids to translate complex numeric nutrition information, reducing the nutritional knowledge, cognitive effort and processing time required. Experts have underscored the importance of identifying strategies to communicate complicated nutrition information to consumers in meaningful ways, rather than relying exclusively on numeric data (e.g. kilocalories, grams, milligrams, percentages).33 The current study tested the application of interpretational aids on calories and negative nutrients only; further research is needed to identify if and how this approach could be applied to positive nutrients.

Similar to a previously published study,34 a large proportion of participants had difficulty manipulating nutrition information to calculate the nutrient content of multiple servings of a product, particularly when the task required complex math as well as understanding % DV information. Listing standardized serving-sizes and simple descriptors on NFts improved the participants’ ability to mathematically manipulate nutrition information, particularly in the task requiring them to calculate multiple servings of a product and estimate the corresponding % DV for the larger amount; however, the effect was modest and the majority of participants were still unable to correctly mathematically manipulate and use numeric information presented on labels. One explanation for the overall difficulty in manipulating nutrition information is that these tasks require a relatively substantial amount of time, motivation and effort as well as nutrition knowledge and math skills. To enable quick and easier access to nutrition information, previous studies have suggested adding a second column to the NFt presenting nutrient and calorie information for an entire package.35 This potential modification may help consumers estimate the nutrient profile of products containing multiple servings. However, Roberto and Khandpur36 noted that providing additional information may increase label complexity. Additional research should compare the dual and single column labels with simpler presentation formats that provide less information, including listing the total number of servings in an entire package on the NFt.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study did not use probability sampling techniques to select a representative sample of young people from Canada. The sample was intended to provide a heterogeneous cross-section of participants from across Canada for random allocation across NFt conditions. Research has shown that higher levels of income and education are generally associated with better performance on nutritional labelling tasks.19 The proportion in our sample of young adults (19–24 y) with more than a high school education was 76%. Poor performance on these tasks among a highly educated sample suggests that consumer understanding and use of serving size and % DV information could be even lower in other population groups. Although the findings may be generalizable to other Canadians of a similar age, further research is necessary to assess whether similar results would be found among subgroups of young people not captured in this survey, including non-English speakers or those less likely to participate or be recruited onto an online panel. To better simulate a real-world situation, the NFts were displayed on two boxes of hypothetical brands of crackers. Crackers are an appropriate product to test various formats of nutrition labels as they offer many nutritive variations and are not necessarily perceived as healthy or unhealthy. There are numerous studies that use a single pre-packaged product to test the efficacy of various formats of nutrition labels and generalize the findings across products16,36-38. However, replicating this study with other products and categories is recommended, as results may vary. Finally, the current study uses a conventional method for evaluating communication materials and concepts prior to implementation; however, online, experimental studies cannot replicate a real-world shopping experience. Future research should aim to evaluate the effectiveness of changes to NFts on food selection and dietary behaviours in real-world settings.

Conclusion

Both academics and health organizations have recommended improvements to nutrition labelling, including standardizing serving-sizes and adding interpretative labels to % DV information, and these changes are supported by consumers.22,39,40 Proposed changes to nutrition labels are under review in Canada and include standardizing serving-size information within similar product categories and adding an interpretational statement defining what is a little or a lot of the % DV.22 Our research suggests that both of these modifications to the NFt may help young Canadians interpret NFt information when choosing foods, compare information between similar products, and mathematically manipulate numeric information to understand the nutritional content of multiple servings of a product.

Our findings provide preliminary evidence supporting the efficacy of modifications to the NFt on consumer understanding and use of nutrition information. Further research is needed to better understand the efficacy of NFt modifications for supporting more informed food choices across a range of food categories and among adults of other age groups in Canada.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by the Canadian Foundation for Dietetic Research.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 . Country Profiles – GBD Profile Canada [Internet] Washington (DC): Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; [cited 2015 Jul 8]. Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/country_profiles/GBD/ihme_gbd_country_report_canada.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper L, Martin N, Abdelhamid A, Davey Smith G. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD011737. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011737. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strazzulo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdullaha A, Peetersa A, de Courtena M, Stoelwinder J. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89((3)):309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amed S, Dean HJ, Panagiotopoulos C, et al. Type 2 Diabetes, medication-induced diabetes, and monogenic diabetes in Canadian children: a prospective national surveillance study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33((4)):786–91. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shields M. Overweight and obesity among children and youth [Internet]. Health Reports. 2006;17((3)):27–42. [cited 2015 Jul 08] Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-003-x/2005003/article/9277-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health Agency of Canada . Chief Public Health Officer's report on the state of public health in Canada: youth and young adults — life in transition [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2011. [cited 2015 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cphorsphc-respcacsp/2011/index-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribiero RC, Coutinho M, Bramorski MA, Giuliano IC, Pavan J. Association of the waist-to-height ratio with cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents: the Three Cities Heart Study. Int J Prev Med. 2010;1:39–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson MC, Story M, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lytle LA. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: an overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity. 2008;16((10)):2205–11. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson NI, Story M, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Food preparation and purchasing roles among adolescents: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and diet quality. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106((2)):211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn JE, Liu K, Greenland P, Hilner JE, Jacobs DR., Jr Seven-year tracking of dietary factors in young adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18((1)):38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Canada Regulations amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Nutrition Labelling, Nutrient Content Claims and Health Claims) [Internet]. Canada Gazette, Part 2. 137((1)):154. 2003 Jan 1 [cited 2015 Jul 15] Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/gazette/archives/p2/2003/2003-01-01/pdf/g2-13701.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman S, Hammond D, Pillo-Blocka F, Glanville T, Jenkins R. Use of nutritional information in Canada: national trends between 2004 and 2008. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43:356–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emrich TE, Qi Y, Mendoza JE, Lou W, Cohen JE, L’abbe MR. Consumer perceptions of the Nutrition Facts table and front-of-pack nutrition rating systems. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39((4)):417–24. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowburn G, Stockley L. Consumer understanding and use of nutrition labelling: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8((1)):21–8. doi: 10.1079/phn2005666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Strategic Counsel . Canadians' understanding and use of the nutrition facts table: baseline national survey results. 2011;. POR 031-10(HCPOR-10-06) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canadian Food Inspection Agency . Information within the nutrition facts table. Mandatory information and serving size [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Canadian Food Inspection Agency; [modified 2015 Apr 10; cited 2015 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.inspection.gc.ca/food/labelling/food-labelling-for-industry/nutrition-labelling/information-within-the-nutrition-facts-table/eng//1389198568400/1389198597278?chap=1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Government of Canada . Food labels: the percent daily value [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; [modified 2015 May 29; cited 2015 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/eating-nutrition/label-etiquetage/daily-value-valeur-quotidienne-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campos S, Doxey J, Hammond D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14((8)):1496–506. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wartella EA, Lichtenstein AH, Boon CS. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2010. Committee on Examination of Front-of-Package Nutrition Ratings Systems and Symbols; Institute of Medicine Institute of Medicine (IOM) Editors; Phase 1 Report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wojcicki JM, Heyman MB. Adolescent nutritional awareness and use of food labels: results from the National Nutrition Health and Examination Survey. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health Canada . Health Canada’s proposed changes to the format requirements for the display of nutrition and other information on food labels [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2014. Jul 14, [cited 2015 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/consult/2014-format-requirements-exigences-presentation/document-consultation-eng.php#a1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balasubramanian SK, Cole C. Consumers' search and use of nutrition information: the challenge and promise of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act. J Marketing. 2002;66((3)):112–27. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health Canada . Sodium in Canada: recommended intake of sodium [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2012. Jun 08, [cited 2015 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/sodium/index-eng.php#a2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) – Weight history – WHQ: Target group: SPs 16+ [Internet] Atlanta (GA): NHANES; 2011. [cited 2015 Jul 14]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/whq.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleich SN, Pollack KM. The publics’ understanding of daily caloric recommendations and their perceptions of calorie posting in chain restaurants. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elbel B. Consumer estimation of recommended and actual calories at fast food restaurants. Obesity. 2011;19:1971–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krukowski RA, Harvey-Berino J, Kolodinsky J, Narsana RT, Desisto TP. Consumers may not use or understand calorie labeling in restaurants. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:917–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health Canada . Food and nutrition: estimated energy requirements [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; [modified 2014 Mar 20; cited 2015 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/basics-base/1_1_1-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackison D, Wrieden WL, Anderson AS. Validity and reliability testing developed to assess consumers' use, understanding, and perceptions of food labels. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64((2)):210–7. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohr GS, Lichtenstein DR, Janiszewski C. The effect of marketer-suggested serving size on consumer responses: the unintended consequences of consumer attention to calorie information. J Marketing. 2012;76((59)):75. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wartella EA, Lichtenstein AH, Yaktine A, Nathan R. Front-of-package nutrition rating systems and symbols: promoting healthier choices. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2011. Oct, Committee on Examination of Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols (Phase II) editors; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Herpen E, Hieke S, van Trijp H, C.M Inferring product healthfulness from nutrition labelling. The influence of reference points. Appetite. 2014;72:138–49. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31((5)):391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antonuk B, Block LG. The effect of single serving versus entire package nutritional information on consumption norms and actual consumption of a snack food. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38((6)):365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hieke S, Wilczynski P. Colour me in – an empirical study on consumer responses to the traffic light signposting system in nutrition labelling. Public Health Nutr. 2013;15((5)):773–82. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrews J, Burton S, Kees J. Is simpler always better? Consumer evaluations of front-of-package nutrition symbols. J Public Policy & Marketing. 2011;30((2)):175–90. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamlin R, McNeill L, Moore V. The impact of front-of-pack nutrition labels on consumer product evaluation and choice: an experimental study. Public Health Nutr. 18((12)):2126–34. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberto CA, Khandpur N. Improving the design of nutrition labels to promote healthier food choices and reasonable portion sizes. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38( Suppl 1):S25–33. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverglade B, Ringel Heller I. Food labeling chaos: the case for reform [Internet] Washington (DC): Center for Science in the Public Interest; 2010. [cited 2015 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.cspinet.org/new/pdf/food_labeling_chaos_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]