Abstract

Coronary heart disease (CHD) represents a major global health burden. However, despite the well-known influence that dietary habits exert over the progression of this disease, there are no well-established and scientifically sound dietary approaches to prevent the onset of clinical outcomes in secondary prevention. The objective of the CORonary Diet Intervention with Olive oil and cardiovascular PREVention study (CORDIOPREV study, clinical trials number NCT00924937) is to compare the ability of a Mediterranean diet rich in virgin olive oil versus a low-fat diet to influence the composite incidence of cardiovascular events after 7 years, in subjects with documented CHD at baseline. For this purpose, we enrolled 1002 coronary patients from Spain. Baseline assessment (2009–12) included detailed interviews and measurements to assess dietary, social and biological variables. Results of baseline characteristics: The CORDIOPREV study in Spain describes a population with a high BMI (37.2% overweight and 56.3% obesity), with a median of LDL-cholesterol of 88.5 mg/dL (70.6% of the patients having <100 mg/dL, and 20.3% patients < 70 mg/dL). 9.6% of the participants were active smokers, and 64.4% were former smokers. Metabolic Syndrome was present in 58% of this population. To sum up, we describe here the rationale, methods and baseline characteristics of the CORDIOPREV study, which will test for the first time the efficacy of a Mediterranean Diet rich in extra virgin olive oil as compared with a low-fat diet on the incidence of CHD recurrence in a long term follow-up study.

Keywords: Mediterranean Diet, Coronary Secondary Prevention, Public Health Interventions, Coronary Heart Disease

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of death in Western countries, and according to current estimates, its overall prevalence will continue growing1. The development of this disease is linked to the presence of several risk factors, among them high blood pressure, high low-density cholesterol (LDL), low high-density cholesterol (HDL), Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, smoking and physical inactivity. Of these, the first four are closely related to the type of diet, and their appearance is often associated with the presence of overweight or obesity2. Dietary interventions to reduce the incidence or recurrence of cardiovascular events have been tested, mainly by substituting saturated fatty acid diets for high-carbohydrate or high polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) diets3–10. A third dietary model, the so-called Mediterranean diet, is characterized by a relatively high proportion of fruit, cereals and vegetables; fish and poultry as the main sources of protein, and the use of virgin olive oil as the main source of fat. This dietary pattern is relatively high in total fat (35%) but low in saturated fats (<10%)11. Although the epidemiological evidence points towards a reduction of the incidence of cardiovascular events resulting from this diet 12–19, no evidence from large-scale, long-term clinical trials exists. A recent study, the PREDIMED trial, showed that, after an average of 4.8 years’ follow-up, two slightly different Mediterranean diet models reduced the incidence of a composite of major cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke or death from cardiovascular causes) versus a control diet (following AHA dietary recommendations) in a Spanish population of 7000 participants in primary prevention in subjects at high cardiovascular risk20. However, evidence of the favorable effect of the Mediterranean diet in secondary prevention is much less established. The Lyon study reported a decrease of 50–70% in the recurrence of cardiovascular events after 4 years’ follow-up of a “Mediterranean diet”21. However, this study used canola oil as the main source of fat, a food that is not commonly used in Mediterranean countries. In fact, some of the potential favorable effects of the Mediterranean Diet have been ascribed to the extra virgin olive oil, due to its combination of a high MUFA (MUFA) fat content with minor compounds with various biological properties, such as polyphenols. These include compounds which affect cardiovascular risk factors like blood pressure, lipids, inflammation, oxidation and those which even modulate favourably the relative expression of certain genes22–27.

With the above background, it becomes evident that there is a need for long-term follow up studies evaluating the efficacy of this dietary model on cardiovascular outcomes in secondary prevention. We report here the methods and baseline characteristics of the CORDIOPREV study, which was designed to investigate the efficacy of the Mediterranean diet in the secondary prevention of CHD as compared with a low-fat diet.

OBJECTIVES

The primary outcome of the CORDIOPREV study is to compare the appearance of a composite of cardiovascular events after an average follow-up of 7 years in secondary prevention with two dietary models: a Mediterranean diet (rich in olive oil) and a low-fat diet. The composite outcome includes the following cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction, revascularization, ischemic stroke, documented peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular death.

Pre-specified secondary outcomes include clinical, biochemical and biological factors, and are defined below in the section entitled “Measuring the Effectiveness”.

METHODS AND DESIGN

Overall Design

The CORDIOPREV study (Clinicaltrials.gov number NCT00924937) is a randomized, single blind, controlled dietary intervention trial in CHD patients with high cardiovascular risk, with an intention to treat analysis basis.

The study is being conducted at the Instituto Maimonides de Investigacion Biomedica de Cordoba (IMIBIC), a scientific institute which carries out research into biomedical areas for the Reina Sofia University Hospital, and the University of Cordoba, Spain. The lipids and atherosclerosis unit, internal medicine unit, is also a member of the CIBER Fisiopatologia de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERobn), a national research organization studying obesity and nutrition and their impact on health and disease. Moreover, the leading researchers have established collaboration agreements with national and international research groups to conduct additional ancillary studies.

Study Population

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 1. To sum up, patients were eligible if they were over 20 years old, but under 76, had established CHD without clinical events in the last six months, were believed to be following a long-term dietary intervention and had no severe illnesses or an expected life expectancy of under five years. All the patients gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for CORDIOPREV study.

| Inclusion Criteria in the CORDIOPREV study: |

|

1.- Informed Consent: All participants will agree to being included in the study by signing the protocol approved by the Reina Sofia University Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee. In this written statement of consent, it will state that patients will be chosen for inclusion in the groups on a random basis. 2.- Diagnostic Criteria: The patients were selected with acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction) and high-risk chronic coronary heart disease, according to the following criteria:

|

| Exclusion Criteria |

|

Randomization

The procedure of randomization was carried out so that the assignment to both diets is well-balanced. The randomization was based on the following variables: sex (male, female), age (under and over 60 years old) and previous myocardial infarction (yes, no). With this distribution, eight distinct groups were created, with all the possible combinations of the above factors, and eight different blocks were created to assign the diets (en-bloc randomization). The process of randomization was performed by the Andalusian School of Public Health. The procedure for assigning a diet was as follows: when there was a candidate for randomization, the study dietitians phoned the person in charge of the study in the Andalusian School of Public Health, which communicated the assigned diet to the dietitian. The dietitians were the only members of the intervention team to be aware of the dietary group of each participant. The School of Public Health gave the head of the dietary staff weekly reports with the progress of randomization, and the assigned diets were crossed between each other to validate the correctness of each assignment.

Interventions, subsequent care and follow up visits

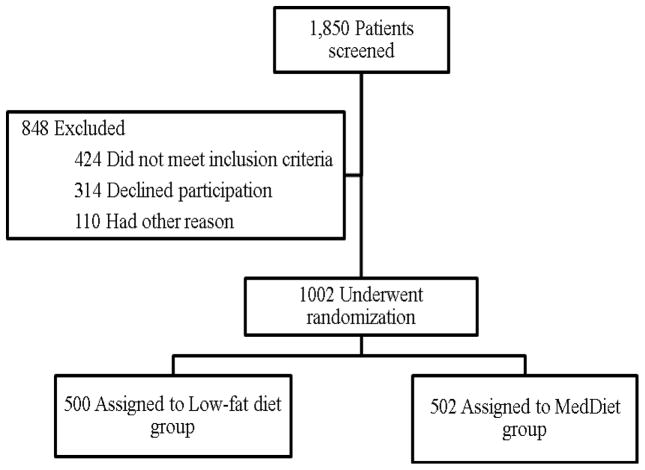

A total of 1002 patients, aged between 20 and 75 years old, were included between July 2009 and February 2012 (Fig 1). The intervention phase is still in progress, and will have a median follow up of seven years. Dietary and clinical monitoring will be carried out by nutritionists and dietitians, as well as internists and cardiologists.

Fig 1.

Screening and randomization of the CordioPrev study

Study diets and dietary assessment: The models of healthy diet are: 1) the Mediterranean diet, with a minimum 35% of calories as fat (22% MUFA fat, 6% PUFA fat and <10% saturated fat), 15% proteins and a maximum of 50% carbohydrates, and 2) the low-fat high complex carbohydrate diet recommended by the National Cholesterol Education Program and the American Heart Association, comprising of <30% total fat (<10% saturated fat, 12–14% MUFA fat and 6–8% PUFA fat), 15% protein and a minimum 55% carbohydrates. In both diets, the cholesterol content was adjusted to <300 mg/day (summarized in Table 2). The objective was not to compare the two different diets defined by a certain percentage of nutrients, but to compare two different dietary models or patterns or two different food pyramids: the dietary pattern of the Mediterranean diet food pyramid versus the dietary pattern recommended by the American Heart Association. Both therapeutic diets should provide a wide variety of foods, including vegetables, fruit, cereals, potatoes, legumes, dairy products, meat and fish. Participants in both intervention groups receive the same intensive dietary counselling. Dietitians administered personalized individual interviews at inclusion and every 6 months, and quarterly group education sessions with up to 20 participants per session and separate sessions for each group. These sessions consisted of informative talks accompanied by written information with detailed descriptions of typical foods for each dietary pattern, seasonal shopping lists, meal plans and recipes. In brief, on the basis of the initial assessment of individual scores of adherence using a 14-item questionnaire, dietitians gave personalized dietary advice to participants randomly assigned to the Mediterranean Diet, with instructions directed to increasing the score, by including, among others, 1) abundant use of olive oil for cooking and dressing, 2) increased consumption of fruit, vegetables, legumes, and fish, 3) reduction in total meat consumption, with white meat recommended instead of red or processed meat, 4) preparation of homemade sauces with tomato, garlic, onion, and spices with olive oil to dress vegetables, pasta, rice and other dishes, 5) avoidance of butter, cream, fast food, sweets, pastries and sugar-sweetened beverages, and 6) in alcohol drinkers, a moderate consumption of red wine. The participants assigned to the Mediterranean Diet were given free extra virgin olive oil (1 litre/week). This amount was not intended to be for the exclusive use of the participant, but for the family to use at home if needed. The participants were not told to use all the oil, but just as much as they needed in their regular diet. The extra virgin olive oil was provided by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero, and always contained >75% of MUFA, > 300 ppm of phenolic compounds and <12% saturated fats (laboratory authorization number A-033-AU, Consejeria De Agricultura, Pesca Y Desarrollo Rural, Junta de Andalucia). The participants randomized to the low-fat diet received recommendations focused on limiting all types of fat, from both animal and vegetable sources, and on increasing the intake of complex carbohydrates. The participants also received free food packs incorporating the main food components of this dietary pattern. No energy restriction was administered, nor was physical activity promoted specifically by the study team. Energy and nutrient intakes were calculated from Spanish food composition tables28–29. A table of interventions and follow-up is described in Table 3. Baseline and annuals visit included: 1) collection of biological samples: 2) a short questionnaire about lifestyle variables, medical conditions, and use of medication, 3) a 14-item questionnaire of adherence to the Mediterranean Diet30 4) a 137-item validated food frequency questionnaire31–32, and 5) the validated Spanish version of the Minnesota Leisure-Time Physical Activity questionnaire33 and the validated SF36 quality of life questionnaire34. Weight, height and waist circumference were measured using standardized procedures. Regular medical visits to ascertain the existence of clinical, prescription drugs or other health changes of the patients are carried out (see Table 3), or additionally on demand, when the patients attend dietary visits and report any changes in their health or treatment.

Table 2.

Energy composition of the two dietary models.

| NUTRIENTS | MEDITERRANEAN DIET | LOW FAT DIET |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | Usual intake, no energy restriction | Usual intake, no energy restriction |

| Carbohydrates | <50 % of total calories | > 55 % of total calories |

| Proteins | 15 % of total calories | 15 % of total calories |

| Total Fat | >35 % of total calories | < 30% of total calories |

| SAFA | < 10% of total calories | < 10% of total calories |

| MUFA | 22 % of total calories | 12–14 % of total calories |

| PUFA | 6 % of total calories | 6–8 % of total calories |

| Cholesterol | < 300 mg | < 300 mg |

SAFA: saturated fatty acid; MUFA: monounsatured fatty acid; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid; mg: milligrams

Table 3.

Table of interventions and follow up. BP, blood pressure. (a) includes direct measurements of weight, height and waist circumference, and (b) only if necessary.

| Item/Measurements | Brief description | Baseline | Number of yearly measurements

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | |||

| Eligibility questionnaire | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General questionnaire a | Personal and family history, medical conditions, medications, anthropometry, BP, smoking, alcohol intake | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Informed Consent | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Randomization | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Follow-up questionnairea | Symptoms and conditions, marital status, job, medications, anthropometry, BP | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Review prior/concomitant medications and Event Questionnaire b | |||||||

| Tolerance questionnaire | Adverse experiences | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Socio-economic questionnaire | Socio-demographic and economic characteristics, marital status, job, level of education | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Circadian chronotype questionnaires | Horne-Östberg Morningness- Eveningness Questionnaire (Spanish version), sleep diaries | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) | Validated tool for screening cognitive function | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) or Yesavage | Validated tool for identifying depression in the elderly (Spanish version) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Health related quality of life | Validated 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Physical activity questionnaire | Validated Minnesota questionnaire | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) | Validated 137-item FFQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14-item MedDiet questionnaire | MedDiet adherence tool | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 9-item Low Fat Diet questionnaire | Low-fat Diet adherence tool | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Dietary reinforcement | Face-to-face and telephone interviews | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Group education sessions | Separate sessions for each group (20 participants/session) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Dispensing study foods | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Blood sample | Lipids, glucose, renal function, transaminases, blood count and others | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Urine sample | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Stool sample | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Insulin resistance test/Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Postprandial lipaemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Intima-media thickness (IMT) study | Carotid-Wall Intima–Media Thickness measurement | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Brachial Artery Reactivity study | Ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow- mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ankle-brachial index (ABI) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Microvascular endothelial function | Laser doppler flowmetry | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Echocardiography | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

Measuring the Effectiveness

The primary outcome of the CORDIOPREV study is to compare the appearance of a number of cardiovascular events after a median follow-up of 7 years in secondary prevention with two dietary models: a Mediterranean diet (rich in olive oil) or a low-fat diet. The composite outcome includes the following cardiovascular events: myocardial infarction, revascularization, ischemic stroke, documented peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular death.

Pre-specified secondary outcomes are: incidence of intermittent claudication; concentration of LDL cholesterol; lipid-related atherogenic ratios: total cholesterol/HDL and LDL/HDL; metabolic control of carbohydrates (assessed by glycemic and insulin responses to tolerance tests to glucose); metabolic control of lipids and postprandial lipaemia; blood pressure; incidence of malignancy; incidence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; incidence of metabolic syndrome; arrhythmias; an extended composite of heart events (cardiac death, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, revascularization, heart failure, heart transplantation and cardiac arrest), an extended composite of cardiovascular disease progression (cardiac death, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, revascularization, heart failure, heart transplantation, cardiac arrest, stroke and peripheral artery disease), progression of cognitive decline and changes in microbiota. (Supplemental material) Additional secondary outcome measures will be performed in the light of present and/or future knowledge about CHD risk factors, prognostic factors and patho-physiological pathways, and will include, but not be limited to, endothelial function, inflammation, cell biology, molecular biology, proteomics, genetics and epigenetics.

Statistical Methods

Sample Size and Power Calculations:

The sample size and power calculation have been calculated on the following assumptions: an incidence rate in the control group (Low Fat) of 4 events/100 person-years that will amount to 24.9% of absolute cumulative incidence after 7 years, a hazard ratio of 0.7 and a statistical power of 80%, with two tailed alpha=0.05. Under these assumptions, the required sample size was 491 patients in each of the two groups.

The size of the sample for the CORDIOPREV study was initially calculated for a cardiovascular disease recurrence of 35% in the control group (Low Fat) and of 25% in the intervention (Mediterranean Diet) in 5 years, with an annual loss of 2%, an alpha error = 0.05 and a power of 0.90 (minimum sample size: 874 patients) of a composite endpoint that included cardiac death, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, revascularization, heart failure, heart transplantation, cardiac arrest, stroke, peripheral artery disease or any other manifestation of cardiovascular disease. In the meeting of the external advisory board in the third year of the study, and according to recent cardiovascular studies, the advisory board recommended limiting the definition of cardiovascular events to those finally included in the study, and which are defined above. Subsequently, based on the lower number of expected events, the final calculations for sample size and power were set as above.

Primary statistical analysis

This study will be analyzed under the principle of “intention-to-treat”

Statistical comparisons will be performed using 2-sided significance tests.

The primary statistical comparison will be the log-rank analysis using the Kaplan-Meier survival estimates, and the “time-to event” analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model. To adjust for heterogeneity among the subjects, the Cox model will be adjusted for several baseline covariates including age and sex. The level of significance for all the analyses will be α=0.05. If the study does not meet the superiority significance criterion, the non-inferiority of the Mediterranean Diet will be tested and established if the upper 95% CI for the estimated hazard ratio falls below 1.10.

Secondary statistical analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of the secondary outcomes, statistical tests will be chosen individually for each outcome. As an example, recently published papers from CordioPrev dealing with genetics or postprandial lipemia used ANOVA tests for quantitative variables and Chi-square for qualitative variables35–40. As a general rule, all levels of significance for regular tests will be set at α=0.05, and Parametric tests will be used whenever possible. Individual specific statistical tests will be performed when needed. An example of this could be the case of large-scale genetic tests or GWA (genome wide analysis). These types of tests are dependent on the specific hypothesis and cannot be pre-specified.

Intermediate analysis

The interim analysis has been planned for October 2016 and 2017. Following the O’Brien Fleming rule, the pre-specified ps for the anticipated end of the study are 0.014 and 0.045 respectively.

Rationale for collaborations, ascertaining events and ethics

The excellent characterization and control of the CORDIOPREV study, with biological, psychological, vascular, genetic, metabolic and socio-economic tests will allow us to study the effects of the dietary intervention in CHD patients using an integrated approach. This wealth of data and the uniqueness of the study will draw the interest of other researchers and facilitate collaborations to investigate other aspects of the study which were not contemplated in the original design.

The existence of primary and secondary outcomes will be monitored by the information provided by the researchers in the case report forms, the scheduled visits in Table 3 and the institutional computer records. In any case, all patients who do not attend a programmed visit will be contacted to find out the cause of the absence, and to carry out a final study visit. The outcomes are ascertained on a yearly basis by a Clinical Events Committee whose members are blinded to the intervention group. During the programmed visits, patient compliance is checked, based on the scores of adherence to the Mediterranean and low-fat dietary patterns, and by measuring selected biological plasma variables, such as the fatty acids profile. The dietary patterns are based on those used in the PREDIMED study 20, 30. The characteristics of the CORDIOPREV study have been previously released in Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00924937). The local Ethics Committee approved the trial protocol, which follows the Helsinki declaration and the charter of good clinical practices. The experimental protocol conforms to international ethical standards and written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

RESULTS OF BASELINE MEASUREMENTS

Up to February 2012, a total of 1002 participants were included in the CORDIOPREV study. Table 4 shows baseline characteristics. The mean age was 59.5 years. The subjects were predominantly male (83.5%), former smokers (64.6%) and consumers of alcohol (82.6%), mostly in moderatation (<14 g/d, mainly red wine). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and the low-fat scores were 8.78 and 3.81 for the whole sample (regardless of the randomization group to which they were assigned), on scores that ranged from 0–14 for the Mediterranean20, 30 and 0–9 for the low fat20 diet. The prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome was 58% (n=581) in this set of patients, which is in accordance with similar studies41.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of the CORDIOPREV study.

| All patients (n=1002) | Mediterranean Diet group (n=502) | Low-Fat Diet group (n=500) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.5 (0.2) | 59.7 (0.4) | 59.5 (0.4) | NS |

| Male/Female, n | 837/165 | 420/82 | 417/83 | NS |

| Metabolic Syndrome, % | 58.0 | 55.6 | 60.4 | NS |

| SBP, mmHg | 138.8 (0.6) | 138.5 (0.9) | 139.0 (0.9) | NS |

| DBP, mmHg | 77.2 (0.3) | 77.2 (0.5) | 77.3 (0.5) | NS |

| Weight, Kg | 85.1 (0.4) | 84.9 (0.6) | 85.4 (0.7) | NS |

| Height, m | 1.7 (0.0) | 1.7 (0.0) | 1.7 (0.0) | NS |

| Waist circumference, cm | 105.1 (0.3) | 104.9 (0.5) | 105.4 (0.5) | NS |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.1 (0.1) | 31.0 (0.1) | 31.2 (0.2) | NS |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dl | 159.0 (1.0) | 159.1 (1.5) | 159.0 (1.3) | NS |

| HDL-c, mg/dl | 42.2 (0.3) | 42.3 (0.5) | 42.1 (0.5) | NS |

| LDL-c, mg/dl | 88.5 (0.8) | 88.9 (1.2) | 88.2 (1.1) | NS |

| APO-A, mg/dl | 129.6 (0.7) | 129.7 (1.0) | 129.5 (0.9) | NS |

| APO-B, mg/dl | 73.6 (0.5) | 73.6 (0.8) | 73.7 (0.8) | NS |

| TG, mg/dl | 135.4 (2.2) | 134.8 (3.1) | 136.0 (3.2) | NS |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose, mg/dl | 113.7 (1.2) | 114.7 (1.8) | 112.8 (1.6) | NS |

| Family history of premature coronary artery disease, % | 14.9 | 14.9 | 14.8 | NS |

| Family history of DM, % | 46.7 | 45.6 | 47.8 | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 32.3 | 31.9 | 32.8 | NS |

| Hypertension, % | 68.5 | 69.2 | 67.9 | NS |

| Normal systolic function (LVEF ≥50%), % | 94.9 | 94.3 | 95.6 | NS |

| History of myocardial infarction, % | 61.9 | 62.2 | 61.6 | NS |

| History of CABG, % | 3.2 | 3.8 | 2.6 | NS |

| history of PCI, % | 91.5 | 91.2 | 91.8 | NS |

| Current smoker, % | 9.7 | 8.7 | 10.7 | NS |

| Former smoker, % | 64.6 | 63.9 | 65.2 | NS |

| History of stroke or TIA, % | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.0 | NS |

| History of peripheral vascular disease, % | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.8 | NS |

| History of prior malignancy, % | 2.6 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 0.04 |

| Baseline medication, % | ||||

| Antiplatelets | 96.6 | 96.9 | 96.4 | NS |

| Statins | 85.6 | 84.9 | 86.4 | NS |

Data are given as Mean (SE) value or percentage of participants unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations:APO-A, apolipoprotein A1; APO-B, apolipoprotein B; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, Coronary artery bypass grafting; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NS, not significant (p-value>0.05); PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TG, triglycerides. SI conversion factors: To convert to millimol per liter, multiply by 0.0259 for HDL-C, by 0.0113 for triglycerides, and by 0.0555 for glucose; to convert insulin to picomol per liter, multiply by 6.945.

We used unpaired T-tests for quantitative variables and Chi-Square for categorical.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The evidence for the influence of the Mediterranean diet on the clinical course of CHD is sparse. Despite the well-established healthy effects of this dietary pattern on multiple cardiovascular risk factors, either traditional ones such as lipids or hypertension, or new emerging ones (endothelial function, oxidative stress, inflammation, obesity, metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes mellitus)14–15, 24, 42–44, there is a paucity of studies evaluating its effectiveness in reducing the onset of cardiovascular complications in coronary patients. The CORDIOPREV study will explore the ability of the Mediterranean diet to reduce the progression of CHD, comparing its results with the low-fat model, in a long-term (7 years) intervention study. The results of the CORDIOPREV study may test the existence of a causal link between the Mediterranean diet and the reduction in cardiovascular events observed in epidemiological studies. Although, due to the longitudinal character of CORDIOPREV, the clinical outcomes will not be unveiled until the end of the intervention periods, several papers have been already published from baseline data from the CORDIOPREV study which have yielded useful insights about genetics, human metabolism or inflammation.35–40 From the conceptual point of view, this study will fill the gap in long-term studies on secondary prevention using dietary approaches. Moreover, it will contribute to our understanding of the use of more personalized strategies. In terms of the methodological components, we should highlight the randomization process carried out by an external body, the large sample size of the study, the strict follow-up protocols and the array of biological samples collected and stored, ranging from microbiota to urine, DNA or endothelial cells, etc. The main weaknesses of the study are those inherent to all long-term intervention studies. On the one hand, it is impossible to guarantee that no patients tell their doctor what their dietary intervention group is; although the standard operation procedures of the study prohibits patients from telling their GP about the diet and from telling those involved in the study (except dietitians) what their dietary intervention group is, it could occur. On the other hand, it is difficult to maintaining the initial sample size, due to losses in the follow up. This is especially important in the subset of patients randomized to the low-fat diet, as this is not a usual dietary pattern in a Mediterranean setting. Although we have established several layers of internal controls to ascertain adherence to the diet, the nature of the study in the “real world setting” contributes to potential deviations from a strict dietary adherence. However, they will also provide more useful results, as they will be applicable to real-life scenarios.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We present the rationale and methods of the CORDIOPREV study.

Mediterranean versus Low-fat diet on cardiovascular outcomes, secondary prevention.

1st large (n=1002), long-term (median 7 years) study with these characteristics.

Acknowledgments

Funding and acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública (EASP), and especially Dr. Antonio Daponte for performing the randomization process. We also want to thank Dr. Miguel Angel Martinez González for his valuable help in the statistical approach. The CORDIOPREV study is supported by the Fundacion Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero. The main sponsor agreed to participate in the study because when it started, there were no full-length studies evaluating the effect of an olive oil-based Mediterranean diet on coronary secondary prevention, although there were many observational studies and studies evaluating risk factors which indicated that it could have a favourable effect. The sponsor was not involved in the design or carrying out the study, and its participation was limited to funding and providing the olive oil used in the study. We also received additional funding from CITOLIVA, CEAS, Junta de Andalucia (Consejeria de Salud, Consejeria de Agricultura y Pesca, Consejeria de Innovacion, Ciencia y Empresa), Diputaciones de Jaen y Cordoba, Centro de Excelencia en Investigacion sobre Aceite de Oliva y Salud and Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Medio Rural y Marino and the Spanish Government. It was also partly supported by research grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion (AGL2009-122270 to J L-M, FIS PI10/01041 to P P-M, FIS PI13/00023 to J D-L); Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (AGL2012/39615 to J L-M); Consejeria de Salud, Junta de Andalucia (PI0193/09 to J L-M, PI-0252/09 to J D-L, and PI-0058/10 to P P-M, PI-0206-2013 to A G-R); Proyecto de Excelencia, Consejería de Economía, Innovación, Ciencia y Empleo (CVI-7450 to J L-M); Francisco Gomez-Delgado is supported by an ISCIII research contract (Programa Rio-Hortega). The study was also co-financed by the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). The CIBEROBN is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. The authors have declared no conflict of interest. There are no ties with industry regarding this paper. We would like to thank to the Cardiology Unit at IMIBIC/University Hospital Reina Sofia, for their valuable help in the recruitment for the present study.

Footnotes

RCT# NCT0092493741

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren WM, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012): The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Atherosclerosis. 2012;223(1):1–68. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1083–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, Rogers S, Holliday RM, Sweetnam PM, et al. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART) Lancet. 1989;2(8666):757–61. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Mamelle N, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, et al. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1994;343(8911):1454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hjermann I, Velve Byre K, Holme I, Leren P. Effect of diet and smoking intervention on the incidence of coronary heart disease. Report from the Oslo Study Group of a randomised trial in healthy men. Lancet. 1981;2(8259):1303–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leren P. The Oslo diet-heart study. Eleven-year report. Circulation. 1970;42(5):935–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.42.5.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, Armstrong WT, Ports TA, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet. 1990;336(8708):129–33. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91656-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turpeinen O, Karvonen MJ, Pekkarinen M, Miettinen M, Elosuo R, Paavilainen E. Dietary prevention of coronary heart disease: the Finnish Mental Hospital Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1979;8(2):99–118. doi: 10.1093/ije/8.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts GF, Jackson P, Mandalia S, Brunt JN, Lewis ES, Coltart DJ, et al. Nutrient intake and progression of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73(5):328–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts GF, Lewis B, Brunt JN, Lewis ES, Coltart DJ, Smith LD, et al. Effects on coronary artery disease of lipid-lowering diet, or diet plus cholestyramine, in the St Thomas’ Atherosclerosis Regression Study (STARS) Lancet. 1992;339(8793):563–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90863-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, de Jesus JM, Houston Miller N, Hubbard VS, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S76–99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babio N, Bullo M, Basora J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fernandez-Ballart J, Marquez-Sandoval F, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of metabolic syndrome and its components. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19(8):563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diez-Espino J, Buil-Cosiales P, Serrano-Martinez M, Toledo E, Salas-Salvado J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and HbA1c level. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;58(1):74–8. doi: 10.1159/000324718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estruch R. Anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet: the experience of the PREDIMED study. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69(3):333–40. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estruch R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Corella D, Salas-Salvado J, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Covas MI, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(1):1–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Corella D, Salas-Salvado J, Ros E, Covas MI, Fiol M, et al. Cohort Profile: Design and methods of the PREDIMED study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):377–385. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salas-Salvado J, Bullo M, Babio N, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Ibarrola-Jurado N, Basora J, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):14–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Mediterranean diet and health status: an updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(12):2769–82. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013003169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, Covas MI, Corella D, Aros F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99(6):779–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giugliano D, Esposito K. Mediterranean diet and metabolic diseases. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(1):63–8. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282f2fa4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kontou N, Psaltopoulou T, Panagiotakos D, Dimopoulos MA, Linos A. The mediterranean diet in cancer prevention: a review. J Med Food. 2011;14(10):1065–78. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Miranda J, Perez-Jimenez F, Ros E, De Caterina R, Badimon L, Covas MI, et al. Olive oil and health: summary of the II international conference on olive oil and health consensus report, Jaen and Cordoba (Spain) 2008. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20(4):284–94. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solfrizzi V, Panza F, Frisardi V, Seripa D, Logroscino G, Imbimbo BP, et al. Diet and Alzheimer’s disease risk factors or prevention: the current evidence. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(5):677–708. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tangney CC, Kwasny MJ, Li H, Wilson RS, Evans DA, Morris MC. Adherence to a Mediterranean-type dietary pattern and cognitive decline in a community population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(3):601–7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.007369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett WC. The Mediterranean diet: science and practice. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(1A):105–10. doi: 10.1079/phn2005931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Cuadrado C. Tablas de composición de alimentos y guía de prácticas. Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide (Grupo Anaya, SA); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mataix J, García L, Mañas M, Martínez E, Llopis J. Tabla de composición de alimentos españoles. Granada: Universidad de Granada; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fernandez-Jarne E, Serrano-Martinez M, Wright M, Gomez-Gracia E. Development of a short dietary intake questionnaire for the quantitative estimation of adherence to a cardioprotective Mediterranean diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(11):1550–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez-Ballart JD, Pinol JL, Zazpe I, Corella D, Carrasco P, Toledo E, et al. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(12):1808–16. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin-Moreno JM, Boyle P, Gorgojo L, Maisonneuve P, Fernandez-Rodriguez JC, Salvini S, et al. Development and validation of a food frequency questionnaire in Spain. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(3):512–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Jr, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(12):741–55. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Rajmil L, Rebollo P, Permanyer-Miralda G, Quintana JM, et al. The Spanish version of the Short Form 36 Health Survey: a decade of experience and new developments. Gac Sanit. 2005;19(2):135–50. doi: 10.1157/13074369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanco-Rojo R, Alcala-Diaz JF, Wopereis S, Perez-Martinez P, Quintana-Navarro GM, Marin C, et al. The insulin resistance phenotype (muscle or liver) interacts with the type of diet to determine changes in disposition index after 2 years of intervention: the CORDIOPREV-DIAB randomised clinical trial. Diabetologia. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomez-Delgado F, Garcia-Rios A, Alcala-Diaz JF, Rangel-Zuniga O, Delgado-Lista J, Yubero-Serrano EM, et al. Chronic consumption of a low-fat diet improves cardiometabolic risk factors according to the CLOCK gene in patients with coronary heart disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59(12):2556–64. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Martinez P, Alcala-Diaz JF, Delgado-Lista J, Garcia-Rios A, Gomez-Delgado F, Marin-Hinojosa C, et al. Metabolic phenotypes of obesity influence triglyceride and inflammation homoeostasis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44(11):1053–64. doi: 10.1111/eci.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alcala-Diaz JF, Delgado-Lista J, Perez-Martinez P, Garcia-Rios A, Marin C, Quintana-Navarro GM, et al. Hypertriglyceridemia influences the degree of postprandial lipemic response in patients with metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease: from the CORDIOPREV study. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez-Delgado F, Alcala-Diaz JF, Garcia-Rios A, Delgado-Lista J, Ortiz-Morales A, Rangel-Zuniga O, et al. Polymorphism at the TNF-alpha gene interacts with Mediterranean diet to influence triglyceride metabolism and inflammation status in metabolic syndrome patients: From the CORDIOPREV clinical trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58(7):1519–27. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Rios A, Gomez-Delgado FJ, Garaulet M, Alcala-Diaz JF, Delgado-Lista FJ, Marin C, et al. Beneficial effect of CLOCK gene polymorphism rs1801260 in combination with low-fat diet on insulin metabolism in the patients with metabolic syndrome. Chronobiol Int. 2014;31(3):401–8. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.864300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Prevalence and profile of metabolic syndrome in patients following acute coronary events and effects of therapeutic lifestyle change with cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(1):50–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fito M, Guxens M, Corella D, Saez G, Estruch R, de la Torre R, et al. Effect of a traditional Mediterranean diet on lipoprotein oxidation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(11):1195–203. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M, Serra-Majem L, Lairon D, Estruch R, Trichopoulou A. Mediterranean food pattern and the primary prevention of chronic disease: recent developments. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(Suppl 1):S111–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez-Tainta A, Estruch R, Bullo M, Corella D, Gomez-Gracia E, Fiol M, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet and reduced prevalence of clustered cardiovascular risk factors in a cohort of 3,204 high-risk patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15(5):589–93. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328308ba61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.