Abstract

Tumor microenvironments have a crucial role in cancer initiation and progression, and share many molecular and pathological features with wound healing process. Unless treated, tumors, however, do not heal in contrast to wounds that heal within a limited time framework. Wounds heal in coordination of a myriad of types of cells, particularly endothelial cells, leukocytes, and fibroblasts. Similar sets of cells also contribute to cancer initiation and progression, and as a consequence, anti-cancer treatment strategies have been proposed and tested by targeting endothelial cells and/or leukocytes. Compared with endothelial cells and leukocytes, less attention has been paid to the roles of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), fibroblasts present in tumor tissues, because their heterogeneity hinders the elucidation on them at cellular and molecular levels. Here, we will discuss the origin of CAFs and their crucial roles in cancer initiation and progression, and the possibility to develop a novel type of anti-cancer treatment by manipulating the migration and functions of CAFs.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Drug resistance, Extracellular matrix, Immune evasion, Transforming growth factor-β, Invasion, Metastasis

Core tip: Tumor microenvironments have a crucial role in cancer initiation and progression, and consist of various types of cells, such as endothelial cells, leukocytes, and fibroblasts. Compared with endothelial cells and leukocytes, less attention has been paid to the roles of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), fibroblasts present in tumor tissues, because their heterogeneity hinders the elucidation on them at cellular and molecular levels. Here, we will discuss the origin of CAFs and their crucial roles in cancer initiation and progression, and the possibility to develop a novel type of anti-cancer treatment by manipulating the migration and functions of CAFs.

INTRODUCTION

Dvorak proposed that tumors are wounds that do not heal[1], based on his discovery of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is produced in wound healing sites as well as tumor sites[2] and can account for chronic hyperpermeability-mediated fibrin deposition in solid tumors and in early stages of wound healing[3]. Moreover, solid tumors and wound healing process share many pathological and molecular features.

Irrespective of the causes and the severities of wounds, healing proceeds to repair the structure and functions of injured organs and tissues, through a series of processes; hemostasis, humoral inflammation with microvascular permeability and extravascular clotting, cellular inflammation with inflammatory cell infiltration, angiogenesis, and generation of mature connective tissue stroma[4]. These steps proceed through the interaction between the parenchymal cells and the stroma, a complex mixture of inflammatory cells, matrix proteins, and tissue cells such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Injured organs and tissues are completely replaced by proliferating parenchymal cells in the case of acute and mild wound, but if not replenished completely, they are filled with connective tissue. Tumor cells, regardless of their site of origin, behave like parenchymal cells in normal tissues and proliferate by interacting with the stroma[4].

Fibroblasts are a major cell type within the stroma and contribute to tissue remodeling in development and tissue homeostasis, by providing structural scaffolding and growth regulatory mediators. Moreover, following tissue injury, fibroblasts exhibit an activated and contractile phenotype with enhanced expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and are referred to as myofibroblasts[5]. Myofibroblasts synthesize increased amount of various types of collagens and extracellular matrix proteins (ECM) to provide scaffold and to eventually aid in wound repair[5]. Furthermore, the cells are important sources of many growth factors and cytokines that regulate wound healing processes[6].

Primary normal fibroblasts isolated from various human tissues, can restrict the in vitro cell proliferation of various types of human cancer cell lines, under co-culture condition[7]. Indeed, if Nod-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein 6 (NLRP6) is absent in fibroblasts within the stem cell niche in the colon, regeneration of the colonic mucosa and processes of epithelial proliferation and migration are impaired and consequently, colitis-associated tumorigenesis is accelerated in mice[8]. Thus, under normal conditions, fibroblasts work as a sentinel cell to maintain epithelial tissue homeostasis and to prevent initiation of tumorigenesis in colon, in a NLRP6-dependent manner.

Like fibroblasts in wound healing process, fibroblasts present in tumor tissues exhibit an activated and a myofibroblast-like phenotype with α-SMA expression and are referred as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)[9]. In contrast to fibroblasts in normal tissues, CAFs in most solid tumors are presumed to promote tumor development and progression by providing cancer cells with a myriad of growth factors[9,10]. However, in pancreatic ductal cancer, CAFs can deliver immune stimulating signals. As a result, depletion of CAFs induces immunosuppression with increased intra-tumoral regulatory T cells (Tregs) and eventually accelerates tumor progression with reduced survival[11]. Hence, it still remains elusive on the pathophysiological roles of CAFs in the development and progression of solid tumors.

We will herein discuss the pathophysiological roles of CAFs and their clinical relevance mainly in colorectal cancer (CRC), but will mention CAFs in other types of cancer if necessary.

CAFS IN COLITIS-ASSOCIATED COLON CARCINOGENESIS MODEL

Accumulating evidence indicates the crucial contribution of chronic inflammation to tumor development and progression[12]. Colitis-associated colon carcinogenesis (CAC) is one typical example of this pathological process. CAC frequently ensues from chronic intestinal inflammatory changes observed in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis (UC), particularly those with a long duration, extensive involvement, and severe inflammation[13]. Pathological features of UC include mucosal damage and ulceration with prominent leukocyte infiltration, and these changes involve rectum at first and extend proximally.

Oral administration of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) solution to rodents can cause acute inflammatory reaction and ulceration in the entire colon, similar to that observed in human UC patients, and therefore, is widely used to reproduce human UC[14]. Moreover, repeated DSS ingestion alone can cause a small number of colon carcinomas in about a half of mice[15], suggesting that inflammatory response alone can cause colon carcinoma. The incidence of DSS-induced colon carcinogenesis is accelerated and increased by a prior administration of azoxymethane (AOM)[16], which can alone cause colon cancer by inducing O6-methyl guanine formation and mutations of the β catenin gene[17]. Thus, the combined treatment with AOM and DSS is used frequently to recapitulate the molecular mechanisms underlying CAC.

A transcription factor, NF-κB, is a key player in inflammation and its activity is triggered by IκB kinase (IKK) complex, in response to a wide variety of pro-inflammatory stimuli such as infectious agents and pro-inflammatory cytokines[18]. Greten et al[19] demonstrated that IKKβ has crucial roles in AOM/DSS-induced CAC by two distinct pathways; prevention of apoptosis of epithelial cells and enhancement of growth factor expression by myeloid cells. Thus, these observations would indicate the crucial involvement of inflammatory cell infiltration in CAC development. Given the crucial roles of NF-κB in regulation of gene expression and biological functions of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and chemokines[18], we examined the AOM/DSS-induced colon carcinogenesis process by using mice deficient in the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF-R)p55 gene[20]. We revealed that genetic ablation of the TNF-Rp55 gene in myeloid cells resulted in reduction in intracolonic infiltration of inflammatory cells, particularly macrophages, and neovascularization, and subsequent tumor formation. Moreover, a TNF inhibitor reduced tumor progression even when it was administered after multiple tumors developed in colon. Similar phenotypes were observed by genetic inactivation of a macrophage-tropic chemokine receptor, the CCR2 gene, in myeloid cells or the administration of CCR2 inhibitors after multiple colon tumors developed[21].

These observations prompted us to further examine the roles of another macrophage-tropic chemokine, CCL3, and its receptors, CCR1 and CCR5[22]. Mice deficient in CCL3, CCR1, or CCR5 gene, did display marginal inflammatory reactions and subsequently develop few colon tumors when AOM was administered together with 3% DSS ingestion. All wild-type (WT) mice failed to survive 4.5% DSS ingestion, whereas CCL3-, CCR1-, or CCR5-deficient mice survived this high concentration of DSS solution with a prominent mucosal damage and leukocyte infiltration in colon. Interestingly, CCR1-deficient mice developed multiple colon tumors, whereas the same treatment caused only a small number of colon tumors in CCL3- or CCR5-deficient mice (Table 1)[22]. These observations would indicate that inflammatory cell infiltration is necessary but not sufficient for the development of CAC in this model.

Table 1.

Pathological changes in various mice after azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium treatment

| Ingested DSS concentration | Body weight loss (> 20%) | Granulocyte infiltration (> 400/field) | Fibroblast accumulation (> 20% type I collagen+ areas) | Tumor numbers | |

| Wild-type mice | 3.0% | + | + | + | > 20 |

| CCR1-deficient mice | 3.0% | - | - | - | < 5 |

| 4.5% | + | + | + | > 20 | |

| CCR5-deficient mice | 3.0% | - | - | - | < 5 |

| 4.5% | + | + | - | < 7 | |

| CCL3-deficient mice | 3.0% | - | - | - | < 5 |

| 4.5% | + | + | - | < 5 |

Table is prepared according to Sasaki et al[22]. DSS: Dextran sulfate sodium.

The most prominent difference in pathological change is that CCL3- or CCR5-deficient mice exhibited reduced accumulation of CAFs in colon, which was evident in the later phase of CAC in this model, compared with WT or CCR1-deficient mice (Table 1). Several groups including ours further demonstrated that CAFs expressed abundantly growth factors such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)[23], epiregulin[24], and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF)[22] to promote tumor cell proliferation in the later phase of this CAC model. Moreover, the deficiency of the CCR5 gene results in reduced growth of the tumors arising from either subcutaneous or orthotopic intracecum injection of a syngeneic mouse colon adenocarcinoma cell line, colon 26. Furthermore, this attenuated tumor growth was associated with a reduction in type I collagen-positive fibroblast numbers but not inflammatory cell infiltration[22]. These observations would indicate the crucial involvement of CAFs in rather progression of CAC than its development.

ORIGINS OF CAFS

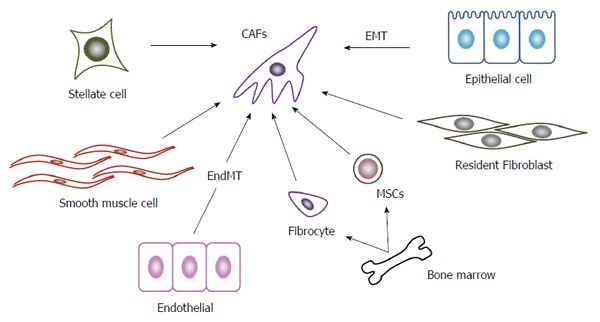

The lack of a specific marker to identify CAF[25] hampers the precise identification of the origin of CAF. α-SMA, a robust CAF marker, is also expressed by normal colonic fibroblasts under in vitro culture conditions[26] and other cell types such as pericytes and smooth muscle cells surrounding vasculature, and cardiomyocytes[27]. There are several additional candidate CAF markers including fibroblast activation protein (FAP)-α[28,29], S100A4/fibroblast specific protein-1[30,31], neuron-glial antigen-2, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor-β, and prolyl 4-hydroxylase[32]. However, these molecules can be expressed by other cell types than CAFs and therefore, are not specific to CAFs. The lack of a definitive maker for CAFs, imply the phenotypical and functional heterogeneity of CAFs in CRC and this assumption is further strengthened by global gene expression profiles[33] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Origin of cancer associated fibroblasts. A variety of cells can generate to CAFs. The most important cellular source of CAFs in CRC is presumed to be resident fibroblasts. Stellate cells in intestine may be able to transform into CAFs similarly as stellate cells in liver and pancreas do. Other potential sources include epithelial cells undergoing EMT, endothelial cells undergoing EndMT, smooth muscle cells, and bone marrow-derived cells including fibrocytes and MSCs. CAFs: Cancer associated fibroblasts; CRC: Colorectal cancer; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; EdnMT: Endothelial-mesenchymal transition; MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells.

The most possible cellular source of CAFs in CRC is resident fibroblasts in colon tissues. Supporting this notion, CAFs in liver metastatic foci of CRC exhibit the similar protein expression pattern as liver resident fibroblasts[34]. Kojima and colleagues demonstrated that resident human mammary fibroblasts progressively convert into CAF-like cells with enhanced α-SMA expression and pro-tumorigenic capacity, during the course of tumor progression in a breast tumor xenograft model[35]. Moreover, these cells express transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and a chemokine, stromal-derived factor (SDF)-1/CXCL12, the molecules which further initiate and maintain the differentiation of fibroblasts into CAF-like and the concurrent tumor-promoting phenotype in an autocrine and amplifying manner[35].

Stellate cells are vitamin A-containing and lipid droplet-containing cells in their quiescence state and are present in various tissues including liver, pancreas, kidney, and intestine[36]. These cells activate α-SMA expression under inflammatory and oncogenic conditions and acquire myofibroblast-like phenotypes as CAFs do. Most of hepatocellular carcinomas arise in a cirrhotic liver with prominent fibrosis. Activated hepatic stellate cells are the major source of extracellular proteins during fibrogenesis. Moreover, they can induce hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth, neovascularization, and immune evasion, to promote tumor progression[37]. Similar to hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer is characterized by a prominent desmoplastic/stromal reaction. Like hepatic stellate cells, activated pancreatic stellate cells can produce abundantly the collagenous stroma of pancreatic cancer. Moreover, these cells can also interact closely with cancer cells to facilitate local tumor growth and distant metastasis, to mediate angiogenesis, and to induce immune evasion[38]. However, it has to be yet determined whether stellate cells in intestine, can also behave in a similar manner in the course of colon carcinogenesis, as those in liver and pancreas do.

Other types of cells are proposed to be a cellular source of CAFs, based on the analyses on other types of cancers than CRC. Accumulating evidence indicates that under chronic inflammatory conditions, epithelial cells can undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to acquire myofibroblast-like phenotypes and to participate in the synthesis of the fibrotic matrix[39]. A breast carcinoma biopsy provided evidence to indicate the occurrence of EMT and a coincidental α-SMA-positive stromal reaction[40]. Moreover, when a mouse breast cancer cell line, MCF-7, was injected into nude mice, together with HBFL-1, a mammary gland epithelial cell line without tumorigenicity, HBFL-1 cells acquired myofibroblast-like phenotypes and conferred a significant 3.5- to 7-fold increase in MCF-7 tumor size in nude mice. Thus, breast cancer can transform its own nonmalignant stroma to facilitate its own growth[40]. Furthermore, when human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI)-resistant lung cancer cells were used as a xenograft model, EMT-derived tumor cells give rise to about a quarter of CAFs, which provide cancer cells with resistance to EGFR-TKI[41]. Meanwhile, several independent groups argue against EMT as the origin of CAFs[42,43].

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are proposed to be an another origin of CAFs, because MSCs and CAFs exhibit similar immunophenotypes and share the potential to differentiate to various types of cell lineages such as adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts[44]. Bone marrow-derived and circulating fibroblast progenitors, fibrocytes, also exhibit similar phenotypic and functional characteristics in chemically induced rat breast carcinogenesis model[45], suggesting that fibrocytes can be an origin of CAFs.

TGF-β1 can induce proliferating endothelial cells to undergo a phenotypic conversion into fibroblast-like cells with the emergence of mesenchymal markers and the reciprocal down-regulation of CD31[46]. Moreover, when endothelial cells were irreversible tagged by crossing Tie2-Cre mice with R26Rosa-lox-Stop-lox-LacZ mice, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) was evident at the invasive front of the tumors in the B16F10 melanoma model and the Rip-Tag2 spontaneous pancreatic carcinoma model[46]. Choi and colleagues further demonstrated that endothelial heat shock protein (a synonym of HSP27 in humans and HSP25 in rodents) has a crucial role in the maintenance of endothelial phenotypes and that its deficiency mediates the EndMT to accelerate fibrosis and eventually tumorigenesis in lungs[47]. Smooth muscle cells can be another source of CAFs in several cancers, particularly prostate cancer. Normal prostate stroma is enriched in smooth muscle cells, but during prostatic carcinogenesis in rats and humans, smooth muscle cells disappear with reciprocal appearance of CAFs, which can promote carcinogenesis in genetically abnormal but non-tumorigenic epithelial cells[48]. Thus, smooth muscle cells may be a source of CAFs in prostate cancer but it remains to be clarified whether CAFs originate from this population in other types of cancer, particularly CRC.

Evidence is accumulating to indicate functional heterogeneity of CAFs in various types of cancers including colon cancer[33]. This heterogeneity may arise from the differences in the origin of CAFs. Alternatively, CAFs are generated by the intricate interactions with tumor microenvironments consisting of cancer cells and other resident cells[10,25]. Thus, the heterogeneity of tumor microenvironments can induce a wide variation in CAFs. Nevertheless, this heterogeneity of CAFs can affect the clinical course of colon cancer patients[49].

RECRUITMENT AND ACTIVATION OF CAFS

Among chemokines, CCL2 and CCL3 can recruit fibroblasts[50], while CXCL12[51], CCL21[52], and CCL3[53] can recruit fibrocytes in chronic inflammation. We proved that CCL3 is produced locally at tumor sites and is associated with CAF accumulation[22,54]. Moreover, in a mouse gastric cancer model, a substantial proportion of CAFs originate from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, which are recruited to tumor site in a TGF-β and CXCL12-dependent manner[55]. Thus, CAF accumulation may be regulated by the cooperation with chemokines and other fibroblast-tropic factors such as TGF-β.

Normal fibroblasts can inhibit in vitro cell proliferation of cancer cells[7]. Moreover, normal intestinal fibroblasts can maintain epithelial homeostasis to prevent carcinogenesis[23]. Thus, malignant cells must reprogram normal fibroblasts into CAFs with protumorigenic activity. This process is mediated by cancer cell-derived factors including TGF-β, CXCL12[35], PDGF[56], and interleukin (IL)-6[57]. On the contrary, several lines of evidence indicate that CAF phenotype can persist in the absence of continued exposure to cancer cell-derived factors[58]. This may be explained by the observation that CAFs increasingly acquire the capacity to express TGF-β and CXCL12, the cytokines which can act to initiate and maintain the differentiation into CAFs in auto-stimulatory and cross-communicating manner[35]. Alternatively, CAF may acquire irreversible genetic and/or epigenetic changes during the course of the differentiation, as similarly observed on tumor endothelial cells[59].

CAFS IN CARCINOGENESIS

Cancer cell growth and stemness

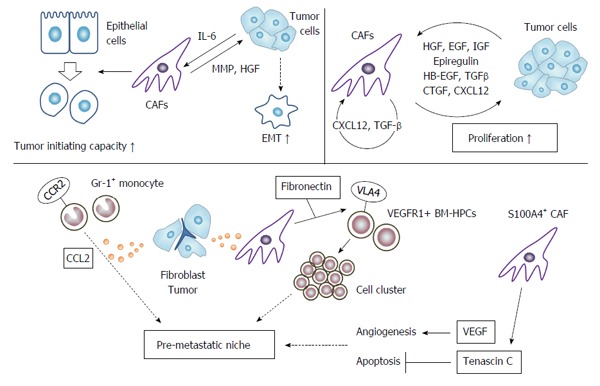

Human pre-malignant prostatic epithelial cells can transform to neoplastic cells when they are in vitro co-cultured with CAFs derived from human prostate cancer tissues[60]. Secreted factors from CAFs are believed to be responsible for this tumor-initiating capacity. Indeed, when human mammary epithelial cells are grafted into immunodeficient mice, together with fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β and/or HGF, the engrafted cells develop into a proliferating tissue that closely resembles human ductal carcinomas[61]. These observations raise the possibility that CAFs can initiate malignant transformation of epithelial cells by secreting these growth factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Action of cancer associated fibroblasts on tumor cells. CAF can induce tumor cells to enhance their tumor initiating capacity (stemness), and to undergo EMT. CAFs provide tumor cells with various growth factors to promote their growth. CAFs can also instigate pro-metastatic niche by inducing tumor cell cluster and angiogenesis, and suppressing tumor cell apoptosis. CAFs: Cancer associated fibroblasts; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor.

Under the influence of cancer cell-derived IL-6, CAFs can secrete metalloproteinases, to stimulate EMT and cancer stem cell phenotypes in prostate cancer[62]. CAFs in colon cancer secrete HGF, activate β-catenin-dependent transcription and subsequently induce cancer stem cell clonogenicity[63]. Moreover, CAF-derived HGF also restores the cancer stem cell phenotype in more differentiated tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, human colon cancer-derived and chemotherapy-treated CAFs produce abundantly interleukin-17A (IL-17A), which increases chemotherapy-resistant cancer stem cells[64].

CAFs produce various growth factors and cytokines, which can promote cancer cell proliferation; HGF[23], EGF[65], epiregulin[24], HB-EGF[22], insulin-like growth factor (IGF)[66], TGF-β[35] connective tissue growth factor[67], and CXC12[58]. Actually, most of these growth factors can be produced by cancer cells and can enhance the growth of CAFs. Moreover, CAF-derived TGF-β and CXCL12 affect CAF proliferation in an autocrine manner[35]. Thus, these growth factors form a vicious positive feedback loop between cancer cells and CAFs, and may eventually accelerate tumor progression.

Thus, CAFs can contribute to tumor development and progression by initiating malignant transformation, enhancing the proliferation of cancer cells, and inducing the cancer stem cell phenotype.

Cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis

Colon cancer cell lines exhibit enhanced migratory ability in a wound healing assay and increased clonogenic capacity in the presence of CAF-derived conditioned media, compared with normal fibroblast-derived conditioned media[26]. Moreover, co-injection of CAFs with a human colon cancer cell line into nude mice, significantly enhances tumor growth with increased tumor cell proliferation, compared with normal fibroblasts[26]. Gene ontology analysis further reveals that genes overexpressed in CAFs are associated with biological processes such as development (TGFB2, PDGFC, cMET, CADM1, WNT1) and cell-cell signaling (TFAP2C, NTF-3, SEMA5A, EFNB2, INHBA)[26]. These gene products can modulate the functions of cancer cells to promote their invasion and metastasis (Figure 2).

CAFs expressed various matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and MMP-mediated ECM degradation results in proteolytic destruction of basement membrane and aids tumor cells to invade surrounding tissues[68]. Moreover, MMP-mediated enhanced invasiveness also involves proteinase-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) expressed on cancer cell surface. CAF-derived MMP-1 cleaves PAR1 at its proper site to deliver PAR1-mediated signaling pathway in cancer cells, which is associated with cancer cell migration and invasion[69].

Fibroblasts as well as tumor cells produce abundantly CCL2, which recruits Gr-1-positive, CCR2-expressing inflammatory monocytes into lung[70]. Recruited inflammatory monocytes subsequently instigate a pre-metastatic niche, which favors lung metastasis of mouse mammary cancer. A pre-metastatic niche can be formed by direct actions by CAFs[71]. S100A4-positive CAFs produce abundantly VEGF-A, which plays an important role in the establishment of an angiogenic microenvironment at the metastatic site to facilitate colonization. Moreover, S100A4-positive CAFs produce tenascin-C to provide cancer cells with protection from apoptosis.

Gene expression-based classification systems have identified an aggressive colon cancer subtype with mesenchymal features, possibly reflecting EMT of tumor cells. Comparative analysis of stromahigh and stromalow CRC shows that the neoplastic cells in stromahigh tumors express specific EMT drivers including ZEB2, TWIST1, and TWIST2[72]. Moreover, type I collagen dominates the extracellular matrix in these aggressive colon cancer with EMT markers. Mimicking the tumor microenvironment, Matrigel enriched with type I collagen can induce colon cancer cells to express tumor-specific mesenchymal gene, to suppress gene expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4, a transcriptional activator of epithelial differentiation, and its target genes, and to invade collectively patient-derived colon tumor organoids[72]. Thus, CAF-derived type I collagen can induce EMT in cancer cells to promote their invasion.

Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells expressing VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR1) home to tumor-specific pre-metastatic sites[73]. Primary tumor-derived factors induce resident fibroblast in pre-metastatic sites to express fibronectin, which interacts with VLA-4 on VEGFR1-positive cells to induce cell clusters and to promote subsequently pre-metastatic niche formation. Fibronectin expression in fibroblasts is regulated by sphingosine-1-phosphate (SIP)-SIP receptor-STAT3 pathway[74].

CAFs can activate STAT3 pathway in cancer cells to promote malignant progression. CRCs frequently display mutational inactivation of the TGF-β pathway with elevated TGF-β production. Actually, cancer cell-derived TGF-β stimulates CAFs to secrete IL-11, which triggers gp130/STAT3 signaling in tumor cells[75]. This cross-talk can provide metastatic cells with a survival advantage.

Drug resistance

CAF-derived ECM has profound impact on cancer chemotherapy[76]. ECM forms a physical barrier and as a consequence, most anti-cancer drugs show limited penetration into solid tumors[77]. Moreover, cancer cells acquire chemoresistance through the activation of various pro-survival signal pathways including PI3K/Akt, Erk, Rho/Rock, and p53 after binding to ECM[76]. Adhesion of small cell lung cancer cells to ECM confers resistance to chemotherapeutic agents because the adhesion activates β1 integrin-stimulated tyrosine kinase to eventually suppress chemotherapy-induced apoptosis[78]. Similar mechanisms may also work in the case of resistance to radiotherapy in glioma cells[79].

In addition to ECM, CAF-derived soluble factors have been demonstrated to be involved in drug resistance. CAF-derived CXCL12 mediate drug resistance to conventional chemotherapeutics[80]. This resistance can arise from the ability of CXCL12 to promote cancer cell survival by activating focal adhesion kinase, Erk, and Akt, β-catenin and NF-κB, in CXCR4-expressing cancer cells[81].

The presence of driver mutations in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) pathways positions RTKs for potential targets for cancer therapy and accordingly, many anti-cancer drugs have been developed by targeting these RTKs[82]. However, RTK-mediated signals converge on common critical downstream cell-survival effectors such as PI3K and Erk, and consequently, most cells can be rescued from drug sensitivity by simply exposing them to one or more other unrelated RTK ligands. Among these RTK ligands, HGF confers resistance to the BRAF inhibitor in BRAF-mutant melanoma cells[83]. Likewise, CAF-derived HGF can confer the resistance to EGF-receptor inhibitors to human non-small cell lung cancer cells which is otherwise sensitive to the inhibitors[84].

CRC initiating cells (CICs) are resistant to conventional chemotherapy in cell-autonomous assays, but CIC chemoresistance is also increased by CAFs. Comparative analysis of matched CRC specimens from patients before and after cytotoxic treatment revealed a significant increase in CAFs after cytotoxic treatment[64]. Chemotherapy-treated human CAFs promoted CIC self-renewal and in vivo tumor growth associated with increased secretion of specific cytokines and chemokines, including IL-17A. Exogenous IL-17A increased CIC self-renewal and invasion, and targeting IL-17A signaling impaired CIC growth. Notably, IL-17A was overexpressed by colorectal CAFs in response to chemotherapy and this observation was validated directly in patient-derived specimens without culture[64]. These data suggest that chemotherapy induces remodeling of the tumor microenvironment through activating CAFs to secrete cytokines such as IL-17.

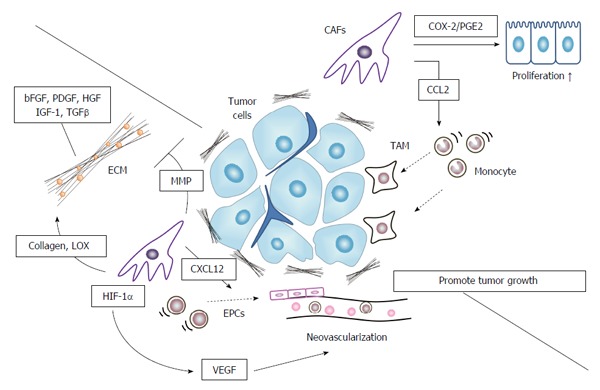

Tumor microenvironments

Inflammation, particularly chronic one, is closely associated with tumorigenesis of various types of cancer[12,85]. CAFs, as a major cellular component of cancer-associated inflammation, mediate tumor-enhancing inflammation by expressing a proinflammatory gene signature in an NF-κB-dependent manner[86]. NF-κB activation enhanced the expression of several chemokines such as CCL2 and proinflammatory genes such as cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) in CAFs. CAF-derived CCL2 mediates the recruitment of blood monocytes to tumor sites[87], favoring the generation of tumor-associated macrophages with a potent pro-tumorigenic activity. Simultaneously, COX-2 generates prostaglandin E2, which can promote both normal and malignant colonic epithelial cell proliferation[88,89] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cancer associated fibroblasts in tumor microenvironment formation. CAFs promote pro-tumorigenic microenvironment by producing extracellular matrix to provide tumor cells with a growth advantage, recruiting tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to foster tumor cell growth, and inducing neovascularization. CAFs: Cancer associated fibroblasts; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; ECM: Extracellular matrix proteins; EPCs: Endothelial progenitor cells; MMP: Matrix metalloproteinase; HIF-1α: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α.

Another prominent feature of CAFs is their ability to synthesize ECM, which can serve as a reservoir for various growth factors such as TGF-β, bFGF, PDGF, HGF, and IGF-1[90]. In response to mechanical stress present in tumor tissues, CAFs exhibit an increase in contractility, which can augment the production of collagen[91]. Moreover, CAFs synthesize the specific ECM including type I collagen, oncofetal nectin splice variants, periostin, and hyaluronan, and as a consequence, remodel ECM to promote tumor growth[90]. CAFs also express abundantly lysyl oxidase (LOX), an enzyme responsible for cross-linking type I collagen. LOX-mediated cross-linking and the resultant tumor tissue stiffness are associated with tumorigenesis[92]. Mechanical stress activates CAFs to express members of MMPs, which regulate the degradation of ECM[90]. MMP-mediated ECM degradation can also promote cancer cell invasion[68].

Tumor microenvironment is characterized by abundant neovascularization, and this process can be induced by CAFs. CAF-induced MMP activation degrades ECM and eventually causes neovascularization[68]. Moreover, CAFs, particularly those in invasive margins, are a rich source of a CXC chemokine, SDF-1/CXCL12[58], which mediates the recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells and subsequent tumor neovascularization. Furthermore, hypoxia can induces CAFs to express a transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, which in turn induces the expression of VEGF, a potent angiogenic factor[93]. VEGF production by CAFs can be further enhanced by CAF-derived IL-6, whose expression can be augmented in the presence of colon cancer cells[94].

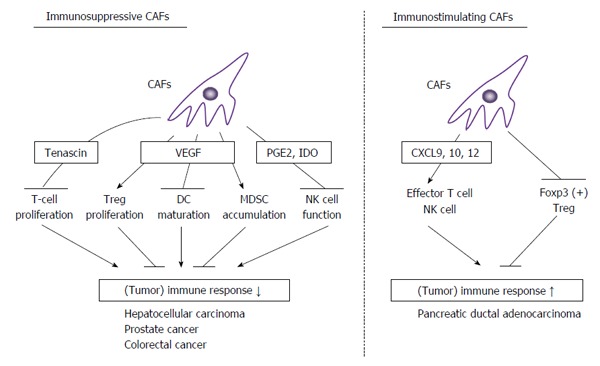

Tumor immunity

Direct evidence on the involvement of CAFs in suppressed tumor immunity, comes from the study, which revealed that deletion of FAP-positive stromal cells enhances tumor immunity[28]. This study, however, did not clarify the cellular and molecular mechanisms in detail, but several candidate mechanisms have been proposed. CAF-derived prostaglandin E2 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenease can inhibit natural killer cell functions, thereby contributing to immune escape and subsequent tumor progression[95]. CAF-derived tenascin also contributes to immune suppression at tumor sites. Soluble tenascin inhibits proliferation of human T cells induced by the combination of anti-CD3 antibody and fibronectin. Tenascin further attenuates T cell proliferation driven by IL-2, while it prevents high level induction of IL-2 receptor[96]. Prostate cancer stem-like cells present in the draining lymph nodes use tenascin-C to inhibit T-cell receptor-dependent T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine production, and as a consequence, cancer stem-like cells are protected from T cell-mediated immune surveillance[97] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Double-edged actions of cancer associated fibroblasts in tumor immunity. CAFs exhibit double-edged actions in tumor immunity. In most types of cancers, CAFs can dampen tumor immunity by suppressing T cell proliferation, NK cell activity, and DC maturation, and inducing Treg proliferation and MDSC accumulation. In some types of cancers such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, CAFs can enhance tumor immunity by enhancing effector T cell and NK cell functions and depressing Treg activities. CAFs: Cancer associated fibroblasts; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; MDSC: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells; NK: Natural killer.

CAFs abundantly express TGF-β1, which can suppress the functions of various immune cells, particularly effector T cells and natural killer cells[98]. TGF-β regulates Treg maturation and thereby suppresses immune responses. VEGF is also produced by CAFs and exhibits immunosuppressive effects[99]. VEGF can suppress the maturation of dendritic cell precursors, promote the proliferation of Tregs, and the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) in peripheral immune organs, and thereby inhibits T-cell immune responses.

In vivo vaccination with a DNA vaccine against FAP eliminates CAFs and eventually causes a shift of the immune microenvironment from a Th2 to Th1 polarization. This shift is characterized by increased protein expression of IL-2 and IL-7, suppressed recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), MDSCs, and Tregs, and decreased tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis[100]. These observations suggest the roles of CAFs in intratumor Th2 polarization and subsequent depression of tumor immunity. This Th2 polarization is mediated by CAF-derived thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), which induces in vitro myeloid DCs to up-regulate the TSLP receptor, secrete Th2-attracting chemokines, and acquire TSLP-dependent Th2-polarizing capability in vitro and in vivo[101]. Moreover, CD90-positive CAFs in colon cancer produce IL-6, which induces the polarization of tumor promoting inflammatory T helper 17 cells in infiltrating lymphocytes as well as the expression of cancer stem cell markers in colon cancer cells[102].

CAFs can produce a myriad of chemokines, which can attract and activate immunosuppressive cells, such as M2-polarized TAMs, MDSCs, and Tregs, thereby suppressing tumor immunity[103]. Simultaneously, CAFs can produce chemokines that promote the recruitment of effector T cells and natural killer cells, including CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL12[103]. If the latter chemokines are predominant chemokines produced by CAFs, they can enhance specific tumor immunity instead of suppressing it. Indeed, depletion of CAFs induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival in a mouse pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) model[11]. The immunosuppression is associated with increased Foxp3-positive Treg numbers and can be reversed by the immune checkpoint therapy using anti-CTLA4 antibody. Thus, in this model, CAFs restrain Tregs from expansion to keep tumor cells under immune surveillance.

CAFS AS A PROGNOSIS MARKER IN CRC

CAFs can be a useful marker to predict disease recurrence in patients with various type of cancer[10]. Similar observations are obtained on CAFs in CRC. Tumors with abundant α-SMA-positive CAFs are associated with shorter disease-free survival for stage II and III CRC after curative CRC surgery[104]. Likewise, high intra-tumor stroma proportion was associated with shorter overall and disease-free survival in stage II and stage III CRC patients after curative surgery[105]. CAFs express abundantly FAP-α and SDF-1/CXCL12. Colon cancer patients with high intra-tumor stromal FAP-α expression tend to have more aggressive disease progression and experience metastasis or recurrence[106]. Similarly, intra-tumor FAP-α and SDF-1 expression is shown to be involved in tumor re-growth and recurrence in rectal cancer patients treated with pre-operative chemo-radiation therapy[107].

The analysis was conducted on CAFs established from primary human colon cancer and revealed that CAFs exhibit significant differences in their promigratory effects on cancer cells upon co-culture with cancer cells[33]. Moreover, CAFs’ promigratory effects on cancer cells are associated with fibroblast activation and stemness markers. CAF signature is identified from the gene expression signature derived from the most protumorigenic CAFs and shows a remarkable prognostic value for the clinical outcome of patients with CRC. Berdiel-Acer and colleagues conducted a transcriptomic profile of normal colonic fibroblasts, CAFs at primary tumor and CAFs at liver metastasis sites, and they identified 19-gene classifier that can predict recurrence with high accuracy in patients with CRC and correlates with fibroblast migratory potential[108]. Moreover, this 19-gene classifier can identify low-risk patients very accurately, and this identification is of particular importance for stage II patients, especially T4N0 patients clinically classified as being at high risk, who would benefit from the omission of chemotherapy. The same group further developed a 5-gene classifier for relapse prediction in Stage II/III CRC by analyzing gene expression patterns in CAFs[109]. The 5-gene classifier in CAFs was significantly associated with increased relapse risk and death from CRC among stage II/III patients. These studies also proved the existence of heterogeneity in CAFs in terms of gene expression signatures.

Molecular classification of CRC based on global gene expression profiles have defined three subtypes; chromosomal-instable tumor (CCS1), microsatellite-instable/CpG island methylator (CIMP)-positive tumor (CCS2), microsatellite-stable/CIMP-positive tumor (CCS3)[110]. CCS3 subtype exhibits upregulation of genes involved in matrix remodeling and EMT and has a very poor prognosis. However, a more detailed analysis revealed that their predictive power arises from genes expressed by stromal cells rather than epithelial tumor cells[111]. Moreover, functional studies indicate that CAFs can increase the frequency of tumor-initiating cells and that this enhancing effect is further augmented by TGF-β signaling. Furthermore, poor-prognosis CRC displays a gene program induced by TGF-β in tumor stromal cells. These observations would indicate that CAF-mediated gene expression profiles can be used to predict the prognosis of colon cancer patients.

CAF AS A TARGET FOR CANCER TREATMENT

Kraman and colleagues demonstrated that genetic depletion of FAP-expressing cells causes rapid hypoxic necrosis of both cancer and stromal cells in Lewis lung carcinoma-bearing mice depending on interferon-γ and TNF-α. They also demonstrated that depleting FAP-expressing cells allows immunological control of tumor[28]. However, the same group demonstrated that FAP-positive cells of skeletal muscle are the major local source of follistatin and that those in bone marrow express CXCL12 and kit ligand. As a consequence, experimental ablation of these cells causes loss of muscle mass and a reduction of B-lymphopoiesis and erythropoiesis[29]. Thus, it is probable that depletion of FAP-positive cells in tumor tissue can cause cachexia and anemia, and as a consequence, it may be difficult to target FAP to deplete CAFs.

We demonstrated the crucial involvement of the CCL3-CCR5 axis on AOM/DSS-induced colon carcinogenesis by recruiting and activating CAFs. Systemic delivery of a CCR5-antagonist-expressing vector is well tolerated by tumor-bearing mice and reduces significantly tumor mass together with decreased CAFs, when it is given even after multiple tumors develop[22]. An antagonist to another chemokine, CXCL12, inhibits CAF-mediated integrin β1 clustering at the cell surface and eventually the invasive ability of gastric cancer cells, suggesting that the inhibition of CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling in gastric cancer cells may be a promising therapeutic strategy against gastric cell invasion[112]. Moreover, CAF-derived CXCL12 can provide prostate cancer cells with the chemoresistance to a cytotoxic drug, docetaxel, and a CXCR4 antagonist can sensitize cancer cells to this drug in a subcutaneous xenograft model of prostate cancer[80]. PDAC-bearing mice frequently does not respond to immune checkpoint therapy with anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody despite the presence of tumor-specific CD8-positive cells, but depletion of FAP-positive CAFs uncovers the antitumor effects of anti-PD-L1 antibody and inhibits tumor growth[113]. Moreover, FAP-positive CAFs express CXCL12 and as a consequence, a CXCR4 antagonist also induces rapid T-cell accumulation among cancer cells and acts synergistically with anti-PD-L1 to greatly diminish cancer cells in pancreatic cancer model[113].

Normalization of CAFs is proposed as the strategy targeting CAFs. CAFs in prostate cancer exhibit reduced miR-15 and miR-16 expression, which is associated with the reduced post-transcriptional repression of Fgf-2 and its receptor Fgfr1[114]. The Fgf-2-Fgfr1 axis acts on both stromal and tumor cells to enhance cancer cell survival, proliferation, and migration. Moreover, reconstitution of miR-15 and miR-16 impairs considerably the tumor-supportive capability of stromal cells in vitro and in vivo[114]. Downregulation of miR-31 and miR-214 is observed in CAFs in ovarian cancer and the expression of these miRNAs induces a functional conversion of CAFs into normal fibroblasts[115]. Similar observations were also obtained on miR-31 and miR-148a expression in CAFs[116,117]. Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (Pten) expression in stromal fibroblasts suppresses epithelial mammary tumors. Pten-deficient mammary fibroblasts exhibit reduced miR-320 expression and reciprocally enhanced ETS2 expression, and can accelerate tumorigenicity when co-injected into mice with mouse mammary cancer cells[118]. miR-320 overexpression in fibroblasts reduces their tumorigenic activity upon co-injection with cancer cells[118]. These observations would indicate that the modulation of miRNA expression can reduce the protumorigenic capacity of CAFs, by dedifferentiating CAFs into normal fibroblasts.

Nintedanib is a broad spectrum tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with the VEGF receptor, FGF receptor, and PDGF receptor as target by binding the ATP pocket in a competitively reversible manner and is used as monotherapy for the treatment of idiopathic lung fibrosis (IPF)[119]. Nintedanib reduces lung inflammation and fibrosis in IPF as evidenced by the reduced deposition of type I collagen and the inhibition of fibroblast activation. VEGF, FGF, and PDGF are secreted by CAFs as well as cancer cells and TAMs, and their receptors are expressed by CAFs, cancer cells, and endothelial cells[120]. Moreover, the mechanism of fibroblast activation in IPF closely resembles that in cancer[121]. Hence, nintedanib is proposed to be used as a second line therapy for non-small cell lung cancer in combination with docetaxel[122]. Another anti-fibrotic agent, pirfenidone, is used for the treatment of IPF although its exact molecular mechanisms remain enigmatic[123]. The combination of pirfenidone and cisplatin leads to increased CAF cell death and decreased tumor progression in a human non-small cell lung cancer xenografted model[124]. These observations would indicate that these anti-fibrotic agents may be used for the treatment of cancer with abundant fibrotic changes.

Given the capacity of TGF-β as a potent fibrotic molecule[98], anti-TGF-β monoclonal antibody was developed and tested in clinical trials for several types of cancer. It can induce anti-tumor effects but simultaneously cutaneous keratoacanthomas/squamous cell carcinomas[125]. This may arise from double-edged activities of TGF-β; a tumor suppressor for normal epithelial cells and a tumor driver in tumor microenvironments[98].

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Accumulating evidence indicates the crucial involvement of inflammation in cancer development and progression[12]. Inflammation is a dynamic host response, wherein various types of cells participate in a concerted manner[4]. However, until recently, much attention has been focused on two processes involved in inflammation; neovascularization and inflammatory cell infiltration. Various agents have been developed as anti-cancer drugs, by targeting neovascularization, but with limited success[126]. Despite the remarkable successes of immunotherapies that modulate the adaptive immune system consisting of lymphocytes and dendritic cells[127], the plasticity and the heterogeneity of inflammatory leukocytes, monocytes/macrophages and granulocytes, have hindered the elucidation of the precise roles of these cells in carcinogenesis, and eventually the development of anti-cancer agents targeting inflammatory leukocytes[128]. Under these circumstances, fibroblasts, another type of cells in inflammation, have emerged as an important player in cancer-related inflammation[10,25,129].

CAFs express a NF-κB-dependent gene signature in mouse tumor models of skin, pancreatic and breast cancer[86]. These observations incited two independent groups to conduct fibroblast-specific deletion of the gene of IKKβ, which is indispensable to NF-κB activation and to examine the effects of the gene deletion on AOM/DSS-induced colon carcinogenesis[130,131]. However, the results are completely opposite to each other; Koliaraki et al[130] demonstrated a pro-tumorigenic activity of IKKβ whereas Pallangyo identified IKKβ as a tumor suppressor. A remarkable difference between these two groups seems to arise from the use of the different gene promoters to delete the IKKβ gene. Koliaraki et al[130] used type VI collagen gene promoter whereas Pallangyo and colleagues used type I collagen gene promoter. The IKKβ gene deletion in type VI collagen-positive CAFs, decreased IL-6 production associated with decreased inflammation and suppressed tumor formation[130]. On the contrary, the IKKβ gene deletion in type I collagen-positive CAFs, resulted in enhanced HGF production and subsequent tumor growth promotion[131]. Thus, CAFs as a whole may act to promote carcinogenesis but a part of them, particularly type I collagen-positive ones, may still retain normal fibroblast-like phenotypes and functionality to suppress carcinogenesis, because normal intestinal fibroblasts can regulate intestinal homeostasis to suppress colitis-associated tumorigenesis[23].

Targeting CAFs can be a novel strategy to treat cancer, particularly inflammation-related cancer. In order to advance this strategy, however, more detailed and precise understanding of phenotypical and functional heterogeneity in CAFs is required to identify the CAF subpopulation and/or the molecules, which have crucial roles in cancer development and progression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Dr. Tomohisa Baba (Cancer Research Institute, Kanazawa University) for his critical comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no financial conflict of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 20, 2016

First decision: April 14, 2016

Article in press: May 23, 2016

P- Reviewer: Baba H, Hawinkels L S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983;219:983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM, Manseau EJ, Wiberg L, Churchill WH. Fibrin gel investment associated with line 1 and line 10 solid tumor growth, angiogenesis, and fibroplasia in guinea pigs. Role of cellular immunity, myofibroblasts, microvascular damage, and infarction in line 1 tumor regression. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979;62:1459–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal-redux. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1–11. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klingberg F, Hinz B, White ES. The myofibroblast matrix: implications for tissue repair and fibrosis. J Pathol. 2013;229:298–309. doi: 10.1002/path.4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:835–870. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaberg E, Markasz L, Petranyi G, Stuber G, Dicso F, Alchihabi N, Oláh È, Csízy I, Józsa T, Andrén O, et al. High-throughput live-cell imaging reveals differential inhibition of tumor cell proliferation by human fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2793–2802. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Normand S, Delanoye-Crespin A, Bressenot A, Huot L, Grandjean T, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lemoine Y, Hot D, Chamaillard M. Nod-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein 6 (NLRP6) controls epithelial self-renewal and colorectal carcinogenesis upon injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9601–9606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100981108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Servais C, Erez N. From sentinel cells to inflammatory culprits: cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumour-related inflammation. J Pathol. 2013;229:198–207. doi: 10.1002/path.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madar S, Goldstein I, Rotter V. ‘Cancer associated fibroblasts’--more than meets the eye. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Özdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR, Laklai H, Sugimoto H, Kahlert C, Novitskiy SV, et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713–1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1102942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okayasu I, Hatakeyama S, Yamada M, Ohkusa T, Inagaki Y, Nakaya R. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90290-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okayasu I, Yamada M, Mikami T, Yoshida T, Kanno J, Ohkusa T. Dysplasia and carcinoma development in a repeated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis model. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1078–1083. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okayasu I, Ohkusa T, Kajiura K, Kanno J, Sakamoto S. Promotion of colorectal neoplasia in experimental murine ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;39:87–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi M, Wakabayashi K. Gene mutations and altered gene expression in azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rodents. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:475–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh G, Wang VY, Huang DB, Fusco A. NF-κB regulation: lessons from structures. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:36–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popivanova BK, Kitamura K, Wu Y, Kondo T, Kagaya T, Kaneko S, Oshima M, Fujii C, Mukaida N. Blocking TNF-alpha in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:560–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI32453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popivanova BK, Kostadinova FI, Furuichi K, Shamekh MM, Kondo T, Wada T, Egashira K, Mukaida N. Blockade of a chemokine, CCL2, reduces chronic colitis-associated carcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7884–7892. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki S, Baba T, Shinagawa K, Matsushima K, Mukaida N. Crucial involvement of the CCL3-CCR5 axis-mediated fibroblast accumulation in colitis-associated carcinogenesis in mice. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1297–1306. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koliaraki V, Roulis M, Kollias G. Tpl2 regulates intestinal myofibroblast HGF release to suppress colitis-associated tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4231–4242. doi: 10.1172/JCI63917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neufert C, Becker C, Türeci Ö, Waldner MJ, Backert I, Floh K, Atreya I, Leppkes M, Jefremow A, Vieth M, et al. Tumor fibroblast-derived epiregulin promotes growth of colitis-associated neoplasms through ERK. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1428–1443. doi: 10.1172/JCI63748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Öhlund D, Elyada E, Tuveson D. Fibroblast heterogeneity in the cancer wound. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1503–1523. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berdiel-Acer M, Sanz-Pamplona R, Calon A, Cuadras D, Berenguer A, Sanjuan X, Paules MJ, Salazar R, Moreno V, Batlle E, et al. Differences between CAFs and their paired NCF from adjacent colonic mucosa reveal functional heterogeneity of CAFs, providing prognostic information. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:1290–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens GK. Regulation of differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:487–517. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraman M, Bambrough PJ, Arnold JN, Roberts EW, Magiera L, Jones JO, Gopinathan A, Tuveson DA, Fearon DT. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-alpha. Science. 2010;330:827–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1195300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts EW, Deonarine A, Jones JO, Denton AE, Feig C, Lyons SK, Espeli M, Kraman M, McKenna B, Wells RJ, et al. Depletion of stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-α from skeletal muscle and bone marrow results in cachexia and anemia. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1137–1151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Chen L, Liu X, Kammertoens T, Blankenstein T, Qin Z. Fibroblast-specific protein 1/S100A4-positive cells prevent carcinoma through collagen production and encapsulation of carcinogens. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2770–2781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okada H, Danoff TM, Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Early role of Fsp1 in epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F563–F574. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.4.F563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HM, Jung WH, Koo JS. Expression of cancer-associated fibroblast related proteins in metastatic breast cancer: an immunohistochemical analysis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:222. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0587-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrera M, Islam AB, Herrera A, Martín P, García V, Silva J, Garcia JM, Salas C, Casal I, de Herreros AG, et al. Functional heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblasts from human colon tumors shows specific prognostic gene expression signature. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5914–5926. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mueller L, Goumas FA, Affeldt M, Sandtner S, Gehling UM, Brilloff S, Walter J, Karnatz N, Lamszus K, Rogiers X, et al. Stromal fibroblasts in colorectal liver metastases originate from resident fibroblasts and generate an inflammatory microenvironment. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1608–1618. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kojima Y, Acar A, Eaton EN, Mellody KT, Scheel C, Ben-Porath I, Onder TT, Wang ZC, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA, et al. Autocrine TGF-beta and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) signaling drives the evolution of tumor-promoting mammary stromal myofibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20009–20014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013805107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kordes C, Sawitza I, Häussinger D. Hepatic and pancreatic stellate cells in focus. Biol Chem. 2009;390:1003–1012. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson AI, Conroy KP, Henderson NC. Hepatic stellate cells: central modulators of hepatic carcinogenesis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:63. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0291-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Z, Pothula SP, Wilson JS, Apte MV. Pancreatic cancer and its stroma: a conspiracy theory. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11216–11229. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guarino M, Tosoni A, Nebuloni M. Direct contribution of epithelium to organ fibrosis: epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1365–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petersen OW, Nielsen HL, Gudjonsson T, Villadsen R, Rank F, Niebuhr E, Bissell MJ, Rønnov-Jessen L. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human breast cancer can provide a nonmalignant stroma. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:391–402. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63834-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mink SR, Vashistha S, Zhang W, Hodge A, Agus DB, Jain A. Cancer-associated fibroblasts derived from EGFR-TKI-resistant tumors reverse EGFR pathway inhibition by EGFR-TKIs. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:809–820. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dvořánková B, Smetana K, Říhová B, Kučera J, Mateu R, Szabo P. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are not formed from cancer cells by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in nu/nu mice. Histochem Cell Biol. 2015;143:463–469. doi: 10.1007/s00418-014-1293-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang M, Wu CP, Pan JY, Zheng WW, Cao XJ, Fan GK. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in a human HEp-2 established laryngeal xenografted tumor are not derived from cancer cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition, phenotypically activated but karyotypically normal. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paunescu V, Bojin FM, Tatu CA, Gavriliuc OI, Rosca A, Gruia AT, Tanasie G, Bunu C, Crisnic D, Gherghiceanu M, et al. Tumour-associated fibroblasts and mesenchymal stem cells: more similarities than differences. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:635–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunaydin G, Kesikli SA, Guc D. Cancer associated fibroblasts have phenotypic and functional characteristics similar to the fibrocytes that represent a novel MDSC subset. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1034918. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1034918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeisberg EM, Potenta S, Xie L, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Discovery of endothelial to mesenchymal transition as a source for carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10123–10128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi SH, Nam JK, Kim BY, Jang J, Jin YB, Lee HJ, Park S, Ji YH, Cho J, Lee YJ. HSPB1 Inhibits the Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition to Suppress Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1019–1030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cunha GR, Hayward SW, Wang YZ, Ricke WA. Role of the stromal microenvironment in carcinogenesis of the prostate. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:1–10. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herrera M, Herrera A, Domínguez G, Silva J, García V, García JM, Gómez I, Soldevilla B, Muñoz C, Provencio M, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast and M2 macrophage markers together predict outcome in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:437–444. doi: 10.1111/cas.12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith RE, Strieter RM, Zhang K, Phan SH, Standiford TJ, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL. A role for C-C chemokines in fibrotic lung disease. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:782–787. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:438–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakai N, Wada T, Yokoyama H, Lipp M, Ueha S, Matsushima K, Kaneko S. Secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC/CCL21)/CCR7 signaling regulates fibrocytes in renal fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14098–14103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishida Y, Kimura A, Kondo T, Hayashi T, Ueno M, Takakura N, Matsushima K, Mukaida N. Essential roles of the CC chemokine ligand 3-CC chemokine receptor 5 axis in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis through regulation of macrophage and fibrocyte infiltration. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:843–854. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.051213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu Y, Li YY, Matsushima K, Baba T, Mukaida N. CCL3-CCR5 axis regulates intratumoral accumulation of leukocytes and fibroblasts and promotes angiogenesis in murine lung metastasis process. J Immunol. 2008;181:6384–6393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, Gonda T, Wang SS, Takashi S, Baik GH, Shibata W, Diprete B, Betz KS, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shao ZM, Nguyen M, Barsky SH. Human breast carcinoma desmoplasia is PDGF initiated. Oncogene. 2000;19:4337–4345. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doldi V, Callari M, Giannoni E, D’Aiuto F, Maffezzini M, Valdagni R, Chiarugi P, Gandellini P, Zaffaroni N. Integrated gene and miRNA expression analysis of prostate cancer associated fibroblasts supports a prominent role for interleukin-6 in fibroblast activation. Oncotarget. 2015;6:31441–31460. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, Carey VJ, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hida K, Klagsbrun M. A new perspective on tumor endothelial cells: unexpected chromosome and centrosome abnormalities. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2507–2510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tlsty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuperwasser C, Chavarria T, Wu M, Magrane G, Gray JW, Carey L, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Reconstruction of functionally normal and malignant human breast tissues in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4966–4971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401064101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giannoni E, Bianchini F, Masieri L, Serni S, Torre E, Calorini L, Chiarugi P. Reciprocal activation of prostate cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6945–6956. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vermeulen L, De Sousa E Melo F, van der Heijden M, Cameron K, de Jong JH, Borovski T, Tuynman JB, Todaro M, Merz C, Rodermond H, et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:468–476. doi: 10.1038/ncb2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lotti F, Jarrar AM, Pai RK, Hitomi M, Lathia J, Mace A, Gantt GA, Sukhdeo K, DeVecchio J, Vasanji A, et al. Chemotherapy activates cancer-associated fibroblasts to maintain colorectal cancer-initiating cells by IL-17A. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2851–2872. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubé PE, Yan F, Punit S, Girish N, McElroy SJ, Washington MK, Polk DB. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibits colitis-associated cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2780–2792. doi: 10.1172/JCI62888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sanchez-Lopez E, Flashner-Abramson E, Shalapour S, Zhong Z, Taniguchi K, Levitzki A, Karin M. Targeting colorectal cancer via its microenvironment by inhibiting IGF-1 receptor-insulin receptor substrate and STAT3 signaling. Oncogene. 2016;35:2634–2644. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kubota S, Takigawa M. Cellular and molecular actions of CCN2/CTGF and its role under physiological and pathological conditions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015;128:181–196. doi: 10.1042/CS20140264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boire A, Covic L, Agarwal A, Jacques S, Sherifi S, Kuliopulos A. PAR1 is a matrix metalloprotease-1 receptor that promotes invasion and tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2005;120:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang J, Campion LR, Kaiser EA, Snyder LA, Pollard JW. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Connell JT, Sugimoto H, Cooke VG, MacDonald BA, Mehta AI, LeBleu VS, Dewar R, Rocha RM, Brentani RR, Resnick MB, et al. VEGF-A and Tenascin-C produced by S100A4+ stromal cells are important for metastatic colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16002–16007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109493108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vellinga TT, den Uil S, Rinkes IH, Marvin D, Ponsioen B, Alvarez-Varela A, Fatrai S, Scheele C, Zwijnenburg DA, Snippert H, et al. Collagen-rich stroma in aggressive colon tumors induces mesenchymal gene expression and tumor cell invasion. Oncogene. 2016:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deng J, Liu Y, Lee H, Herrmann A, Zhang W, Zhang C, Shen S, Priceman SJ, Kujawski M, Pal SK, et al. S1PR1-STAT3 signaling is crucial for myeloid cell colonization at future metastatic sites. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Calon A, Espinet E, Palomo-Ponce S, Tauriello DV, Iglesias M, Céspedes MV, Sevillano M, Nadal C, Jung P, Zhang XH, et al. Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-β-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holle AW, Young JL, Spatz JP. In vitro cancer cell-ECM interactions inform in vivo cancer treatment. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;97:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trédan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1441–1454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sethi T, Rintoul RC, Moore SM, MacKinnon AC, Salter D, Choo C, Chilvers ER, Dransfield I, Donnelly SC, Strieter R, et al. Extracellular matrix proteins protect small cell lung cancer cells against apoptosis: a mechanism for small cell lung cancer growth and drug resistance in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:662–668. doi: 10.1038/9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cordes N, Seidler J, Durzok R, Geinitz H, Brakebusch C. beta1-integrin-mediated signaling essentially contributes to cell survival after radiation-induced genotoxic injury. Oncogene. 2006;25:1378–1390. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Domanska UM, Timmer-Bosscha H, Nagengast WB, Oude Munnink TH, Kruizinga RC, Ananias HJ, Kliphuis NM, Huls G, De Vries EG, de Jong IJ, et al. CXCR4 inhibition with AMD3100 sensitizes prostate cancer to docetaxel chemotherapy. Neoplasia. 2012;14:709–718. doi: 10.1593/neo.12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Singh S, Srivastava SK, Bhardwaj A, Owen LB, Singh AP. CXCL12-CXCR4 signalling axis confers gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic cancer cells: a novel target for therapy. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1671–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takeuchi K, Ito F. Receptor tyrosine kinases and targeted cancer therapeutics. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:1774–1780. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilson TR, Fridlyand J, Yan Y, Penuel E, Burton L, Chan E, Peng J, Lin E, Wang Y, Sosman J, et al. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature. 2012;487:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang W, Li Q, Yamada T, Matsumoto K, Matsumoto I, Oda M, Watanabe G, Kayano Y, Nishioka Y, Sone S, et al. Crosstalk to stromal fibroblasts induces resistance of lung cancer to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6630–6638. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Balkwill FR, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation: common themes and therapeutic opportunities. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Erez N, Truitt M, Olson P, Arron ST, Hanahan D. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Are Activated in Incipient Neoplasia to Orchestrate Tumor-Promoting Inflammation in an NF-kappaB-Dependent Manner. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Silzle T, Kreutz M, Dobler MA, Brockhoff G, Knuechel R, Kunz-Schughart LA. Tumor-associated fibroblasts recruit blood monocytes into tumor tissue. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1311–1320. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roulis M, Nikolaou C, Kotsaki E, Kaffe E, Karagianni N, Koliaraki V, Salpea K, Ragoussis J, Aidinis V, Martini E, et al. Intestinal myofibroblast-specific Tpl2-Cox-2-PGE2 pathway links innate sensing to epithelial homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E4658–E4667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415762111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sasaki Y, Nakatani Y, Hara S. Role of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1)-derived prostaglandin E2 in colon carcinogenesis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2015;121:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Malik R, Lelkes PI, Cukierman E. Biomechanical and biochemical remodeling of stromal extracellular matrix in cancer. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Breen EC. Mechanical strain increases type I collagen expression in pulmonary fibroblasts in vitro. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000;88:203–209. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.De Francesco EM, Lappano R, Santolla MF, Marsico S, Caruso A, Maggiolini M. HIF-1α/GPER signaling mediates the expression of VEGF induced by hypoxia in breast cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R64. doi: 10.1186/bcr3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nagasaki T, Hara M, Nakanishi H, Takahashi H, Sato M, Takeyama H. Interleukin-6 released by colon cancer-associated fibroblasts is critical for tumour angiogenesis: anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody suppressed angiogenesis and inhibited tumour-stroma interaction. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:469–478. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li T, Yang Y, Hua X, Wang G, Liu W, Jia C, Tai Y, Zhang Q, Chen G. Hepatocellular carcinoma-associated fibroblasts trigger NK cell dysfunction via PGE2 and IDO. Cancer Lett. 2012;318:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hemesath TJ, Marton LS, Stefansson K. Inhibition of T cell activation by the extracellular matrix protein tenascin. J Immunol. 1994;152:5199–5207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jachetti E, Caputo S, Mazzoleni S, Brambillasca CS, Parigi SM, Grioni M, Piras IS, Restuccia U, Calcinotto A, Freschi M, et al. Tenascin-C Protects Cancer Stem-like Cells from Immune Surveillance by Arresting T-cell Activation. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2095–2108. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Akhurst RJ, Hata A. Targeting the TGFβ signalling pathway in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huang Y, Goel S, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Vascular normalization as an emerging strategy to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2943–2948. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liao D, Luo Y, Markowitz D, Xiang R, Reisfeld RA. Cancer associated fibroblasts promote tumor growth and metastasis by modulating the tumor immune microenvironment in a 4T1 murine breast cancer model. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.De Monte L, Reni M, Tassi E, Clavenna D, Papa I, Recalde H, Braga M, Di Carlo V, Doglioni C, Protti MP. Intratumor T helper type 2 cell infiltrate correlates with cancer-associated fibroblast thymic stromal lymphopoietin production and reduced survival in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2011;208:469–478. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huynh PT, Beswick EJ, Coronado YA, Johnson P, O’Connell MR, Watts T, Singh P, Qiu S, Morris K, Powell DW, et al. CD90(+) stromal cells are the major source of IL-6, which supports cancer stem-like cells and inflammation in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1971–1981. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mukaida N, Baba T. Chemokines in tumor development and progression. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tsujino T, Seshimo I, Yamamoto H, Ngan CY, Ezumi K, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Matsuura N, Monden M. Stromal myofibroblasts predict disease recurrence for colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2082–2090. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Huijbers A, Tollenaar RA, v Pelt GW, Zeestraten EC, Dutton S, McConkey CC, Domingo E, Smit VT, Midgley R, Warren BF, et al. The proportion of tumor-stroma as a strong prognosticator for stage II and III colon cancer patients: validation in the VICTOR trial. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:179–185. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]