Abstract

Background

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma is a rare tumor with a poor prognosis. The purpose of this study is to examine the oncologic outcomes of this disease as they relate to surgical treatment and use of adjuvant therapies.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed all patients treated at our institution for high-grade extraskeletal osteosarcoma of the limb or chest wall. We recorded demographic data, presenting stage, surgical margin, use of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, incidence of local recurrence, metastases, and death. Overall and event-free survival were calculated using Kaplan-Meier survival methods.

Results

There were 12 patients treated with primary wide resection or re-excision of a previously operated tumor bed. Four patients presented with metastases. Seven patients received chemotherapy and four patients received radiation therapy. There were two local recurrences, six patients developed new metastases, and nine patients died. There was no difference in overall survival in patients who received chemotherapy. There was, however, a trend towards increased length of survival in patients who received chemotherapy compared to those who did not (16.4 months vs. 9.3 months, p=0.16).

Conclusions

Despite no difference in overall survival, patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy have a trend towards increased length of survival. We suggest that extraskeletal osteosarcoma be treated with standard osteosarcoma chemotherapy regimens in addition to wide resection.

Introduction

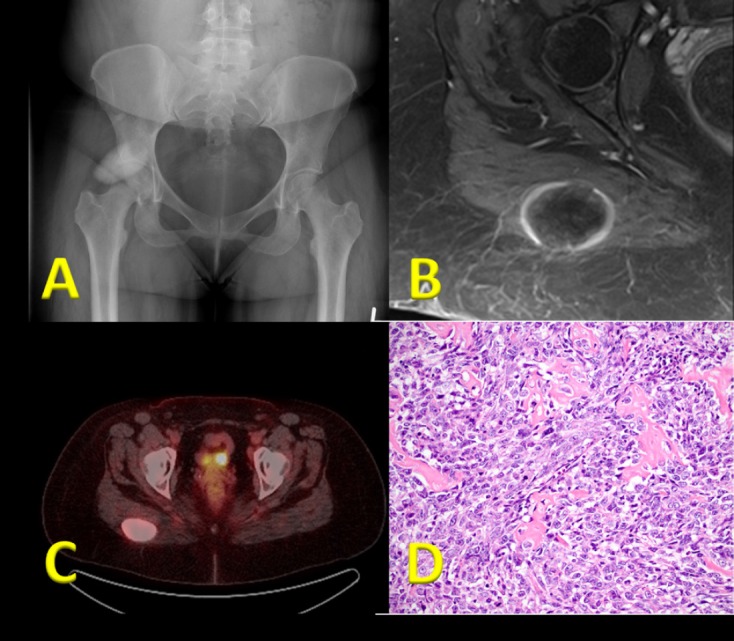

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for approximately 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas and 4% of all osteogenic sarcomas1-4. Unlike conventional osteosarcoma, the extraskeletal variant more commonly affects adults, with most patients being diagnosed after age 405. The lower extremity is the most common location5. The lesion typically demonstrates a central pattern of ossification (Figure 1A) which demonstrates contrast enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography (PET) avidity (Figures 1B and 1C) and histologically mimics its bony counterpart (Figure 1D). The prognosis has been demonstrated to be quite poor with a five-year overall survival rate reported as low as 28%5, with more recent series demonstrating five year disease-specific survival of only 45% for patients presenting with localized disease6,7. There is a paucity of literature regarding this disease and few have attempted to address the role of adjuvant therapies on outcomes8.

Figure 1.

(a) Plain radiographic image demonstrating an ossific mass in the region of the right hip. (b) Axial T1 post-contrast MRI demonstrating the mass arising from the right gluteal musculature with a thin peripheral rim of enhancement. (c) Positron emission tomography scan demonstrating the mass with very high standardized uptake value. (d) Hematoxylin and eosin slide demonstrating immature osteoid formation by malignant appearing spindle cells.

Given the relative rarity of the disease, there is no universally accepted treatment algorithm for extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Unlike its conventional counterpart, the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of extraskeletal osteosarcoma is unclear. Current literature reflects this lack of consensus, with most patient series appearing quite heterogeneous in terms of their treatment algorithms. Recent evidence, however, suggests that outcomes may be improved if extraskeletal osteosarcoma is treated similarly to conventional osteosarcoma with an aggressive chemotherapeutic regimen8,9. A retrospective series of 17 patients published in 2005 found that three year overall survival was 77% when patients were treated with multiagent chemotherapy and surgery; however, this study was limited by short follow-up8. Another report of 20 patients, 15 of which were treated with chemotherapy, noted a 5 year overall survival of 66%9. In contrast, and further strengthening the argument for chemotherapy, a series of 40 patients, in which only two were treated with chemotherapy, reported a 5 year overall survival of 37%10.The objective of the current study is to evaluate the experience of a large referral institution and add to the current literature regarding the multidisciplinary treatment of extraskeletal osteosarcoma.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of our orthopedic oncology database to identify all patients with extraskeletal osteosarcoma treated at our institution. The database contains prospectively collected data on all surgically treated patients treated from 1960 through 2012. The study protocol was approved for a waiver of informed consent by our Institutional Review Board prior to the beginning of data collection. We included all patients treated for high-grade extraskeletal osteosarcoma of the limb or chest wall. All diagnoses were made by a pathologist specializing in musculoskeletal oncology. Surgical notes, radiology reports and actual images, when available, and pathology reports were reviewed to confirm that the mass occurred exclusively in the soft tissues. Exclusion criteria were patients with incomplete charts, those with low-grade tumors, those with periosteal or juxtacortical locations, those who were treated surgically at other institutions, those with unclear survival outcome, or those documented as living but with less than 12 months of clinical follow-up.

We recorded patient demographic data, tumor size and presenting stage, surgical interventions prior to referral to our institution, final surgical margin status after surgery at our institution, use of chemotherapy or radiation, presence of metastatic disease on presentation, development of new metastatic disease during follow-up, development of local recurrence, and death.

Statistical analysis was performed utilizing SPSS software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) was assessed using Kaplan-Meier survivorship methods. Survival was defined from the date of surgery to the date of last followup. Univariate analysis was utilized to assess differences in OS based upon tumor size, prior unplanned excision, type of adjuvant therapy, and presence of local recurrence or metastatic disease. Variables were compared utilizing the Mann-Whitney U test and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We identified 18 patients in our database with extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Three patients were excluded due to having all of their treatment exclusively at outside institutions; three additional cases were excluded, including one case that refused further treatment, a second case that transferred care to another institution prior to treatment, and a third case that did not have clinical follow-up or outcome data beyond one month postoperatively. Twelve patients were available for analysis, with an average age of 60 years ± 16 years. The demographic, treatment, and final outcome data for the 12 patients comprising our case series are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Patient and tumor characteristics, treatment and outcomes for the entire patient cohort.

| Patient | Gender | Age (yrs) | Location | Size (cm) | Volume (cc) | MSTS stage | Prior unplanned excision |

Final Margins | Limb Salvage | Chemo-therapy | Radiation | Status | Follow-up (mos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 72 | distal thigh | 19x7x7 | 931 | IIB | Y | wide | N | N | N | DOD | 2 |

| 2 | M | 76 | chest wall | unknown | unknown | IIA | Y | wide | Y | N | Y | DOD | 9 |

| 3 | M | 83 | proximal thigh |

1.5x2.4x1.4 | 5 | IIA | Y | wide | Y | N | Y | NED | 64 |

| 4 | F | 64 | buttock | 8x5x1.5 | 60 | III | Y | wide | Y | Y | N | DOD | 1 |

| 5 | F | 32 | proximal thigh |

7x6.5x3 | 137 | IIB | N | radical | N | Y | N | DOD | 18 |

| 6 | F | 52 | buttock | 14x14.9x14.8 | 3087 | IIIA | N | wide | Y | Y | N | DOD | 28 |

| 7 | M | 58 | chest wall | 15x17x10 | 2550 | IIIB | N | wide | Y | Y | Y | DOD | 12 |

| 8 | F | 71 | proximal thigh |

13x10x7 | 910 | IIB | N | wide | N | N | N | DOD | 9 |

| 9 | M | 57 | proximalthigh | 10x10x8 | 800 | IIB | Y | wide | N | N | N | DOD | 17 |

| 10 | F | 40 | buttock | 4.3x5.3x5.1 | 116 | III | N | wide | Y | Y | N | NED | 12 |

| 11 | M | 69 | calf | 7x5x3.5 | 123 | IIA | N | wide | Y | Y | N | DOD | 23 |

| 12 | M | 43 | thigh | 4x3.8x2.5 | 38 | IIB | Y | wide | Y | Y | Y | AWD | 12 |

There were six males and six females. Ten tumors were in the lower extremity (6 thigh, 3 buttock, 1 lower leg), and the remaining two tumors were in the chest wall. All were high-grade osteosarcoma at presentation. Two cases are believed to be radiation-associated secondary osteosarcomas in patients who had radiation treatment for unrelated malignancies greater than 15 years prior to extraskeletal osteosarcoma being diagnosed at the margin of their radiation field. The average tumor volume was 796 cc ± 1070 cc (range 5 – 3087 cc).

All of the remaining 12 patients were managed surgically. Surgical intervention at our institution consisted of either a wide or radical resection of the mass or wide or radical re-excision of a previously operated tumor bed. Limb-sparing surgery was performed in eight patients, and four patients were treated with amputation. Seven patients received chemotherapy and four received radiation therapy. Two patients were treated with both chemotherapy and radiation. Three patients were managed with surgery alone. Of those who received chemotherapy, one of the regimens was unknown as that patient was treated at an outside institution with no available records regarding the specifics of their treatment. The other six patients all had doxorubicinbased chemotherapy regimens. Four patients received therapy only in the adjuvant setting and two received both neo-adjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. Of the four patients who were treated with radiation therapy, one was treated pre-operatively with the remaining three being treated post-operatively. All patients treated with adjuvant radiation therapy were treated with a minimum dose of 5040 centigrey (cGy).

There were six unplanned resections prior to referral to our institution. The average tumor volume in patients with an unplanned resection was 367cc, compared to 1154cc in those with no prior unplanned resection (p=0.24).

Of the twelve patients, four (33.3%) had metastatic disease on presentation. Five patients without metastases at diagnosis subsequently developed metastatic disease. There were two local recurrences, at an average of 6 months post-operatively. At the time of final analysis, there were three patients living at an average follow up of 29.3 months (range 12 – 64 months). Two of the three living patients received chemotherapy as part of their treatment. All three patients treated with surgery alone died of disease at 2, 9, and 17 months after surgery.

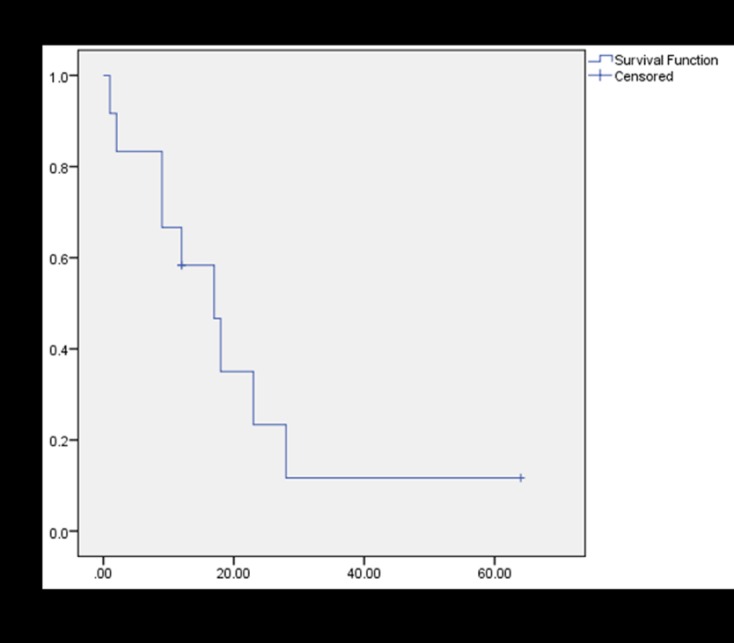

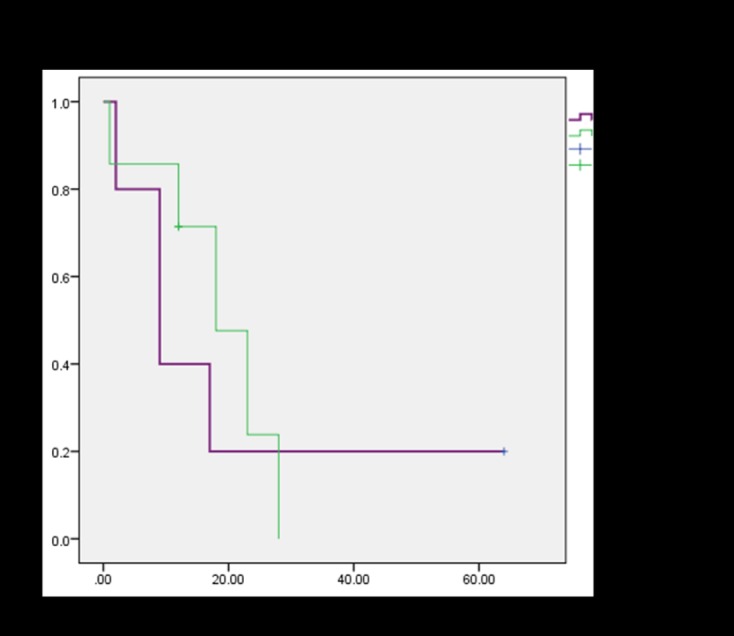

In total, nine patients died of disease at an average of 13 months post-operatively. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated a median survival of 17 months and a 5-year OS of 11.7% (Figure 2). When evaluating OS stratified by patients who received chemotherapy compared to those who did not, there was no significant difference in survival (Figure 3). 5-year EFS was 10.4% (Figure 4). Among the patients who died, there was a trend towards increased length of survival in patients who received chemotherapy compared to those who did not receive chemotherapy (16.4 months vs. 9.3 months, p=0.16), and in those who were managed with primary wide excision compared to unplanned excision prior to referral (18.0 months vs. 7.3 months, p= 0.07). Univariate analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences in survival among tumor volume, previous unplanned excision prior to referral, presentation with metastatic disease, development of new metastases, local recurrence, and use of chemotherapy or radiation (Table II).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of overall survival (OS) for the twelve patients in this series.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of OS in patients who received chemotherapy compared to those who did not.

Figure 4.

kaplan-meier analysis of event-free survival (efs) for the entire patient cohort.

Table II.

Univariate analysis of individual tumor and treatment factors on overall survival.

| Group | Mean Survival (mos) |

95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | ||||

| >500cc | 13.6 | (-4.2, 31.4) | 0.47 | |

| 500cc | 21.7 | (5.4, 38.0) | ||

| Previous Un planned Excision |

0.96 | |||

| Yes | 17.5 | (1.6, 33.4) | ||

| No | 17.0 | (1.1, 32.9) | ||

| Metastases on Presentation |

0.58 | |||

| Yes | 13.3 | (-5.9, 32.4) | ||

| No | 19.3 | (5.7, 32.8) | ||

| New Metastatic Disease |

0.38 | |||

| Yes | 12.8 | (-2.4, 28.1) | ||

| No | 21.7 | (6.4, 36.9) | ||

| Local Recurrence | 0.56 | |||

| Yes | 10.5 | (-16.5, 37.5) | ||

| No | 18.6 | 6.5, 30.7) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.63 | |||

| Yes | 15.1 | 5.4, 21.4) | ||

| No | 20.2 | 0.6, 29.7) | ||

| Radiation Therapy | 0.33 | |||

| Yes | 24.3 | (5.8, 42.7) | ||

| No | 13.8 | (0.7, 26.8) |

Discussion

The largest reported series on extraskeletal osteosarcoma in the literature includes 53 patients over a 30 year time period from a large urban referral institution, highlighting the rarity of this disease7. This is further supported by the fact that the database at our large referral institution identifies only 15 cases spanning a period of over 50 years. Incidence and outcomes from prior reports are summarized in Table III. The rarity of the disease likely contributes to difficulty in making the diagnosis of extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Corroborating this claim, six of the 12 patients in our series had unplanned excisions prior to referral to our institution. Review of the records indicates that several of these patients were erroneously thought to have myositis ossificans. Furthermore, our data indicate that those with unplanned excisions had tumor volumes that were approximately one third the size (367cc vs. 1154cc, respectively) of those who were treated with primary wide or radical excision, which may indicate that the more aggressive behavior was not anticipated based on the modest size of the lesion.

Table III.

Comparison of oncologic outcomes between the current investigation and previously published results of extraskeletal osteosarcoma.

| Study | Years of Enrollment |

# patients | Chemotherapy | Median Survival (mos) |

Overall Survival |

Event Free Survival |

Metasasis Rate |

Local Recurrence Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chung et al. 19874 1946-1982 | 65* | NR | NR | NR | NR | 63% | 43% | |

| Bane et al. 19905 | 1950-1987 | 26 | 13/26 | NR | ~28% | NR | 61.50% | 50% |

| Lee et al. 19959 |

1915-1988 | 40 | 2/40 | NR | 37% | NR | 65% | 45% |

| Ahmad et al. 20026 | 1960-1999 | 30** | NR | NR | 46% 5-year |

47% 5-year |

30% | 20% |

| Goldstein-Jackson et al. 20058 (Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group) |

1986-2002 | 17 | 16/17 | NR | 77% 3- and 5-year |

56% 3- and 5-year \ |

17.60% | 23.50% |

| Torigoe et al. 20079

(Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group) |

1991-2003 | 20 | 15/20 | NR 66% | 5-year | NR | NR | 15.80% |

| Choi et al. 20147 | 1982-2012 | 42*** | 13/42 | 45.8 | 39% 3 year cumulative incidence of death from disease |

50% 3-year | 38% | 19% |

| Current Study | 1960-2012 | 12 | 7/12 | 17 | 11.7% 5-year |

10.4% 5-year |

75% | 16.70% |

Our study noted two cases of local recurrence. The small numbers in our series make definitive conclusions impossible, however, this number compares favorably to other reports in the literature noting recurrence from 45- 50%5,10. Comparatively, the time to local recurrence in our series (mean 6 months) was similar to that reported in the previously noted studies (7-9 months).

Four patients in our series presented with metastatic disease, and there were six cases of new metastatic lesions that developed after or during treatment. One of these new metastatic lesions was a brain metastasis that occurred in a patient who presented initially with only pulmonary metastatic disease. In total, 9/12 (75%) patients developed metastases. This rate is again similar to others reported in the literature which noted rates of metastatic disease to be 62-65%5,10.

The five-year overall survival in this series was 11.7%. This is lower than previously reported8-11. Although no statistically significant difference was found with respect to overall or disease-free survival, two of the three patients who remained living received chemotherapy as a part of their treatment regimen. Furthermore, of those who died, survival was increased at 16.4 months compared to 9.3 months for those who received adjuvant chemotherapy, although this finding did not achieve statistical significance. Previous literature has suggested that survival is improved when extraskeletal osteosarcoma is treated with conventional chemotherapy regimens8. In a 2005 retrospective study from the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group, 17 patients from 17 different institutions were identified with extraskeletal osteosarcoma. All patients, except for one, were treated with chemotherapy according to high-grade conventional osteosarcoma protocols and surgical resection. This study reported an overall survival of 77% at three years and event-free survival of 56% at three years8. Limitations of this investigation include small patient numbers, retrospective design, poor margin descriptions, and short overall time of follow-up. A 2007 study from the Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group inferred that chemotherapy may be beneficial in this disease9. This conclusion was reached by noting a 5 year overall survival of 66% in their series where 15 of 20 patients were treated with chemotherapy, compared to other series noting a significantly lower overall survival rate of 25% when treated without chemotherapy11.

Tumor size has previously been reported to be a major predictor of survival in this disease5. Among the patients who were living, it was noted that their tumor size tended to be smaller at the time of initial presentation, with an average volume of 57 cc. Our analysis showed that tumor volume less than 500 cc had a mean overall survival of 18.7 months, compared to 13.6 months for tumors greater than 500 cc. However, this again failed to reach statistical significance.

As previously noted, the small number of patients in this series, as with many before it, precludes the ability to make any definitive statements regarding the treatment of this exceedingly rare disease. However, our data, when taken together with the modest current literature, suggests that when treated as conventional osteosarcoma, this disease may have an improved prognosis. Standardized treatment protocols and larger scale studies are needed to delineate the role of chemotherapy in this disease.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Dr. MaryBeth Horodyski for her assistance with statistical analysis, and to Jennifer Steshyn for assistance with data accrual.

References

- 1.Wurlitzer F, Ayala L, Romsdahl M. Extraosseous osteogenic sarcoma. Arch Surg. 1972;105(5):691–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180110016006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpert LI, Abaci IF, Werthamer S. Radiationinduced extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1973;31(6):1359–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197306)31:6<1359::aid-cncr2820310609>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sordillo PP, Hajdu SI, Magill GB, Golbey RB. Extraosseous osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1983;51(4):727–34. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830215)51:4<727::aid-cncr2820510429>3.0.co;2-i. A review of 48 patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung EB, Enzinger FM. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1987;60(5):1132–42. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870901)60:5<1132::aid-cncr2820600536>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bane BL, Evans HL, Ro JY, Carrasco CH, Grignon DJ, Benjamin RS, Ayala AG. Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma: A Clinicopathologic Review of 26 Cases. Cancer. 1990;66(12):2762–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900615)65:12<2762::aid-cncr2820651226>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad SA, Patel SR, Ballo MT, Baker TP, Yasko AW, Wang X, Feig BW, Hunt KK, Lin PP, Weber KL, Chen LL, Zagars GK, Pollock RE, Benjamin RS, Pisters PW. Extraosseous osteosarcoma: response to treatment and long-term outcome. J ClinOncol. 2002;20(2):521–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi LE, Healey JH, Kuk D, Brennan MF. Analysis of outcomes in extraskeletal osteosarcoma: a review of fifty-three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):e2. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson Goldstein SY, Gosheger G, Delling G, Berdel WE, Exner GU, Jundt G, Machatschek JN, Zoubek A, Jurgens H, Bielack SS. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma has a favourable prognosis when treated like conventional osteosarcoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131(8):520–6. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0687-7. Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torigoe T, Yazawa Y, Takagi T, Terakado A, Kurosawa H. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma in Japan: multiinstitutional study of 20 patients from the Japanese Musculoskeletal Oncology Group. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12(5):424–9. doi: 10.1007/s00776-007-1164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JSY, Fetsch JF, Wasdhal DA, Lee BP, Pritchard DJ, Nascimento AG. A Review of 40 Patients with Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1995;76(11):2253–59. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2253::aid-cncr2820761112>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen Lidang M, Schumacher B, Jensen Myhre O, Nielsen Steen O, Keller J. Extraskeletal osteosarcomas: a clinicopathologic study of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(5):588–94. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199805000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]