Abstract

In FY 2015, Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program began rewarding hospitals for both their spending and quality performance. This is a sharp departure from the program’s original efforts to reward quality alone. How this change has redistributed hospital bonuses and penalties is unknown. Using data from 2,679 participating hospitals in FY 2014 and FY 2015, we found that the new emphasis on spending in FY 2015 not only rewarded low-spending hospitals, but also some low-quality hospitals. Among low-spending hospitals, 38% received bonuses in FY 2014, and 100% received bonuses in FY 2015. However, low-quality hospitals also became more likely to receive bonuses (0% in FY 2014 vs. 17% in FY 2015). All high-quality hospitals received bonuses in both years. The program should consider incorporating a minimum quality threshold to avoid rewarding low quality, low spending hospitals.

Introduction

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is incentivizing hospitals to provide high-quality, low-cost care.1 In FY 2013, the national Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program linked acute care hospitals’ Medicare payments to performance on quality measures, as authorized by the Affordable Care Act.2–4 In FY 2015, the program added its first spending measure, the Medicare Spending per Beneficiary (MSPB), as a new input in determining if hospitals would receive any of the $1.4 billion in value-based incentive payments.5,6 The addition of this measure, which is comprised of Medicare Part A and B payments from three days prior to hospitalization through 30 days after discharge, is a major shift in CMS’ approach to rewarding and penalizing hospitals.7,8 This marks the first time that most US hospitals have received financial incentives based on both their quality of care and episode-based spending.

With the introduction of this measure, CMS wanted “to identify hospitals involved in the provision of high quality care at a lower cost to Medicare.”6 We do not know how rewarding low-cost care in addition to high-quality care has changed which hospitals are winners or losers in HVBP. If high-quality hospitals are also low-spending hospitals, then rewarding low-spending hospitals would not change which hospitals receive bonuses (or penalties). High-quality hospitals would continue to receive bonuses and low-quality hospitals would continue to receive penalties. On the other hand, some work suggests that quality of care has a weak and inconsistent association with spending.9–13 These studies, however, have not evaluated spending in the context of a longitudinal episode of care that incorporates both pre-admission and post-discharge care. If there is a weak association between quality and episode spending, then the current program may reward those low-quality hospitals that have low episode spending. It may also penalize high-quality hospitals if their episode spending is sufficiently high.

In this analysis, we sought to address the impact of the HVBP program changes on hospital penalties and bonuses. First, what is the relationship between hospital episode spending and other hospital characteristics, such as quality, size, and ownership? Second, what was the effect of adding the new spending measure and decreasing the overall weight given to quality measures, on the distribution and magnitude of hospital bonuses and penalties?

Study Data and Methods

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program Design

Hospitals are eligible to participate in this program if they are acute care hospitals included in the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS), participating in the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program during the performance periods, that do not have citations of deficiencies by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and that meet the required number of cases, measures, or surveys to be accurately measured in each domain.3 This program is unique in that it scores hospitals by both their improvement over time as well as their achievement on individual measures.14

In FY 2014, hospital performance in HVBP was measured across three quality domains, each with different weights: clinical process of care (45%), patient experience of care (30%), and outcomes (25%). In fiscal year 2015, CMS added what they call an efficiency domain (20%) based only on episode-spending, and decreased the overall weight applied to the quality domains to 80% (clinical process of care (20%), patient experience of care (30%), and outcomes (30%)).14

The MSPB, the only input to the new efficiency domain in FY 2015, is based on price-standardized, risk-adjusted Medicare Part A and B payments for all hospitalized patients for an episode of care that starts 3 days prior to admission through 30 days after discharge. In order for a hospital to receive an efficiency domain score, it must have a minimum of 25 eligible episodes of care (more detail in online Appendix).15,16

Data Sources and Sample

We used data from CMS’ Hospital Compare and the Medicare Impact Files to evaluate hospital-level performance on the spending and quality measures in the program, as well as the magnitude of their actual bonus or penalty adjustment factors for both FY 2014 and 2015. We also obtained hospital characteristics using American Hospital Association Annual Survey data from 2013. Our sample included 2,679 hospitals that were eligible to participate in the HVBP program in both FY 2014 and 2015 and that had all pertinent data for our analyses.

Quality and Spending Categories

CMS uses the following method to assign hospitals points for each measure in the program. Hospitals with performance equal to or better than the mean of the top decile receive all possible points, those with rates below the median receive 0 points, and hospitals in the middle of these two cutoffs are assigned a score between 0 and 10.7 We apply the same general approach to categorize hospitals as high quality (performance equal to or better than the mean of the top decile), low quality (performance below the median), or medium quality (all other performance). We applied the same approach for spending. The online Appendix provides more detail.16 In sensitivity analyses, we varied the definitions of low, medium, and high quality or spending (tertiles, quartiles, above or below 1 standard deviation from the mean). For the quality measures, CMS’ achievement distribution cutoffs are based on hospital performance in a baseline period (data from 2010/2011 for FY 2015 penalties and bonuses), while for the spending measure, they are based on scores from the performance period (data from 2012/2013 for FY 2015 penalties and bonuses).6,7

Statistical Analyses

To describe hospital performance on the new CMS measure of episode spending and to provide a sense of where spending differs across hospitals, we compared the pre-admission, index admission, post-acute care, and total episode costs across hospitals by their spending category. We then described how hospitals in each spending category differed across several structural characteristics: number of beds (<200, 200–349, 350–499, 500+), teaching status (none, minor, major), ownership (for profit, non-profit, government), location (urban/rural), and region (Northeast, West, Midwest, and South). We ran bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions to describe the relationship between these hospital characteristics and their odds of being high-spending. To examine the relationship between episode spending and quality in FY 2015, we compared the quality performance of hospitals in different spending categories. Using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple-comparison tests, we evaluated the differences in individual measure performance between high- and low-spending hospitals. We also estimated the correlation coefficients between CMS’ quality and spending domain scores.

To describe the effects of adding a spending measure on the distribution and magnitude of hospital bonuses and penalties in FY 2015, we first ran bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions to characterize the relationship between structural hospital characteristics and the probability of receiving a penalty in FY 2014, and then in FY 2015. We then calculated the percentage of low, medium, and high spending hospitals that received bonuses in FY 2014, and then did the same for FY 2015. We repeated this process using the quality categories. To compare the percent of hospitals receiving bonuses by spending or quality category across the two years, we used a two sample t-test of proportions. Finally, to quantify the magnitude of hospital penalties and bonuses, we summarized actual bonus and penalty amounts for hospitals in FY 2015, by quality and spending categories. We used a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni multiple comparison test to compare the bonus and penalty amounts. This study was declared exempt by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we limit our analysis to hospitals that have complete quality and spending data in both FY 2014 and FY 2015. However, the 2,679 hospitals included in this study comprise 87% of all HVBP participants in FY 2015. Second, CMS does not explicitly label hospitals as low, medium, or high quality/spending hospitals. Nonetheless, we categorize hospitals using the same cutoffs that CMS applies to assign performance points to hospitals.14 We also ran sensitivity analyses using different threshold of low, medium, and high, to determine the robustness of our findings. Finally, our analyses are based on the latest data available for the current fiscal year. It is possible that the relationship between quality and spending will change, either due to the introduction of new measures or due to changes in performance on current measures.

Results

High-spending hospitals spent $5,657 more during an episode of care than low-spending hospitals (Exhibit 1). Post-acute care spending varied widely between low- and high-spending hospitals ($5,473 vs. $9,100), accounting for 64% of the difference in total episode spending across these hospitals. Large hospitals (500+ beds) were more likely to be high-spending than small hospitals (<200 beds) (OR: 2.60, 95% CI: 1.99, 3.38). Major and minor teaching hospitals were also more likely to be high spending than non-teaching hospitals (OR: 1.86 for major, 95% CI: 1.41, 2.45; 1.43 for minor, 95% CI: 1.21, 1.69). A hospital was less likely to be high-spending if it was non-profit (OR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.51, 0.75) or rural (OR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.40). These relationships stayed substantively the same in the multivariate regression, although the association between spending and teaching became insignificant (online Appendix Exhibit A2).16

Exhibit 1.

Total and Component Episode Payments and Hospital Characteristics, by HVBP Spending Categories in FY 2015

| Spending Category | Odds Ratio of being High- Spending |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Low (N=68) |

Medium (N=1,473) |

High (N=1,138) |

||||

| Episode Components | ($) | (%) | ($) | (%) | ($) | (%) | |

| Preadmission | 442 | (3) | 567 | (3) | 618 | (3) | - |

| Index Admission | 8,157 | (58) | 9,590 | (54) | 10,011 | (51) | - |

| PAC | 5,473 | (39) | 7,526 | (43) | 9,100 | (46) | - |

| Total | 14,072 | (100) | 17,683 | (100) | 19,729 | (100) | - |

| Hospital Characteristics | |||||||

| Beds (%) | |||||||

| <200 | 4 | 62 | 33 | Reference | |||

| 200–349 | 1 | 46 | 54 | 2.35 | |||

| 350–499 | 0 | 49 | 51 | 2.10 | |||

| 500+ | 0 | 44 | 56 | 2.60 | |||

| Teaching (%) | |||||||

| None | 3 | 58 | 38 | Reference | |||

| Minor | 2 | 51 | 47 | 1.43 | |||

| Major | 0 | 46 | 54 | 1.86 | |||

| Ownership (%) | |||||||

| For Profit | 1 | 46 | 53 | Reference | |||

| Non-Profit | 3 | 56 | 41 | 0.62 | |||

| Government | 5 | 63 | 33 | 0.43 | |||

| Region (%) | |||||||

| Northeast | 1 | 45 | 54 | Reference | |||

| West | 5 | 64 | 31 | 0.37 | |||

| Midwest | 3 | 59 | 38 | 0.53 | |||

| South | 2 | 53 | 46 | 0.72 | |||

| Location (%) | |||||||

| Urban | 2 | 54 | 44 | Reference | |||

| Rural | 10 | 72 | 17 | 0.26 | |||

SOURCE – Authors’ analysis of Fiscal Year 2015 HVBP Data from CMS Hospital Compare and 2013 AHA Annual Survey Data. NOTES- Low Spending means the Efficiency Domain score is equal to or greater than the mean of the 90th percentile, Medium Spending means that the Efficiency Domain score is greater than or equal to the 50th percentile and less than the mean of the 90th percentile. High Spending means the Efficiency Domain score is smaller than the 50th percentile. Rows may not add up to 100 because of rounding. Odds Ratio shown are from bivariate analysis. All p<0.001 except for “South,” which is p<0.01.

We found a weakly positive relationship between episode spending and overall quality performance (ρ=0.064, p=0.0009). Compared to high-spending hospitals, low-spending hospitals had modestly better patient experience (online Appendix Exhibit A3).16 For example, more patients at low-spending hospitals gave the highest possible rating to their doctors’ communication (81.8% vs. 79.3%, p<0.001). Despite this, the percentage of patients who rated their hospital as being close to the “best hospital possible” were not significantly different (68.7% at low-spending hospitals vs. 68.4% at high-spending hospitals, p=1.00). High-spending hospitals had significantly higher rates of adherence to clinical processes for 7 out of the 12 measures. Outcomes were slightly better at high-spending hospitals compared to low-spending hospitals, but the differences in 30-day mortality rates were not statistically significant. Overall, the magnitude of the differences between high- and low-spending hospitals in terms of quality were modest (online Appendix Exhibit A3), with the differences being more pronounced when stratifying hospitals by their quality (online Appendix Exhibit A4).16

For many types of hospitals, there were substantial changes over time in both the absolute as well as the relative likelihood of receiving a penalty (Exhibit 2). Large hospitals (500+ beds) increased their probability of receiving a penalty by 7 percentage points from FY 2014 (53% received a penalty) to FY 2015 (60% received a penalty). Similarly, there were large increases in the probability of receiving a penalty for major teaching hospitals (9 percentage points), and for-profit hospitals (9 percentage points). Examining data from just FY 2015, large hospitals were more likely to receive a penalty compared to small hospitals (500+ beds OR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.79, 3.05). The odds of receiving a penalty were also much higher in FY 2015 for teaching compared to non-teaching hospitals (minor teaching OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.40, 1.96; major teaching OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.60, 2.82), for-profit compared to non-profit hospitals (non-profit OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.43, 0.64), and urban compared to rural hospitals (rural OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.25, 0.51). In multivariate analyses, our results were qualitatively similar (online Appendix Exhibit A5).16

Exhibit 2.

Probability of Receiving a Penalty by Structural Characteristics in FY 2014 and FY 2015

| FY 2014 | FY 2015 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics |

Percent Receiving Penalty (%) |

Odds Ratio of Receiving Penalty |

95% CI |

Percent Receiving Penalty (%) |

Odds Ratio of Receiving Penalty |

95% CI |

| Beds | ||||||

| <200 | 53 | Ref | - | 39 | Ref | - |

| 200–349 | 54 | 1.03 | 0.86,1.24 | 58 | 2.11 | 1.75,2.54 |

| 350–499 | 56 | 1.13 | 0.88,1.45 | 60 | 2.30 | 1.78,2.96 |

| 500+ | 53 | 0.99 | 0.76,1.29 | 60 | 2.34 | 1.79,3.05 |

| Teaching Status | ||||||

| None | 53 | Ref | - | 42 | Ref | - |

| Minor Teaching | 56 | 1.11 | 0.94,1.31 | 55 | 1.66 | 1.40,1.96 |

| Major Teaching | 52 | 0.97 | 0.74,1.28 | 61 | 2.13 | 1.60,2.82 |

| Ownership | ||||||

| For Profit | 51 | Ref | - | 60 | Ref | - |

| Non-Profit | 53 | 1.08 | 0.89,1.31 | 44 | 0.52 | 0.43,0.64 |

| Government | 63 | 1.66 | 1.26,2.18 | 49 | 0.64 | 0.49,0.83 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 55 | Ref | - | 53 | Ref | - |

| West | 66 | 1.62 | 1.25,2.10 | 54 | 1.05 | 0.82,1.36 |

| Midwest | 45 | 0.66 | 0.52,0.83 | 40 | 0.59 | 0.47,0.75 |

| South | 53 | 0.93 | 0.75,1.16 | 48 | 0.82 | 0.66,1.02 |

| Location | ||||||

| Urban | 54 | Ref | - | 49 | Ref | - |

| Rural | 54 | 1.01 | 0.73,1.38 | 26 | 0.36 | 0.25,0.51 |

SOURCE – Authors’ analysis of Fiscal Years 2014 & 2015 Data from CMS Impact File and 2013 AHA Annual Survey Data. NOTES – Ref means this category was the reference group in the regression. Odds Ratios shown from bivariate analysis.

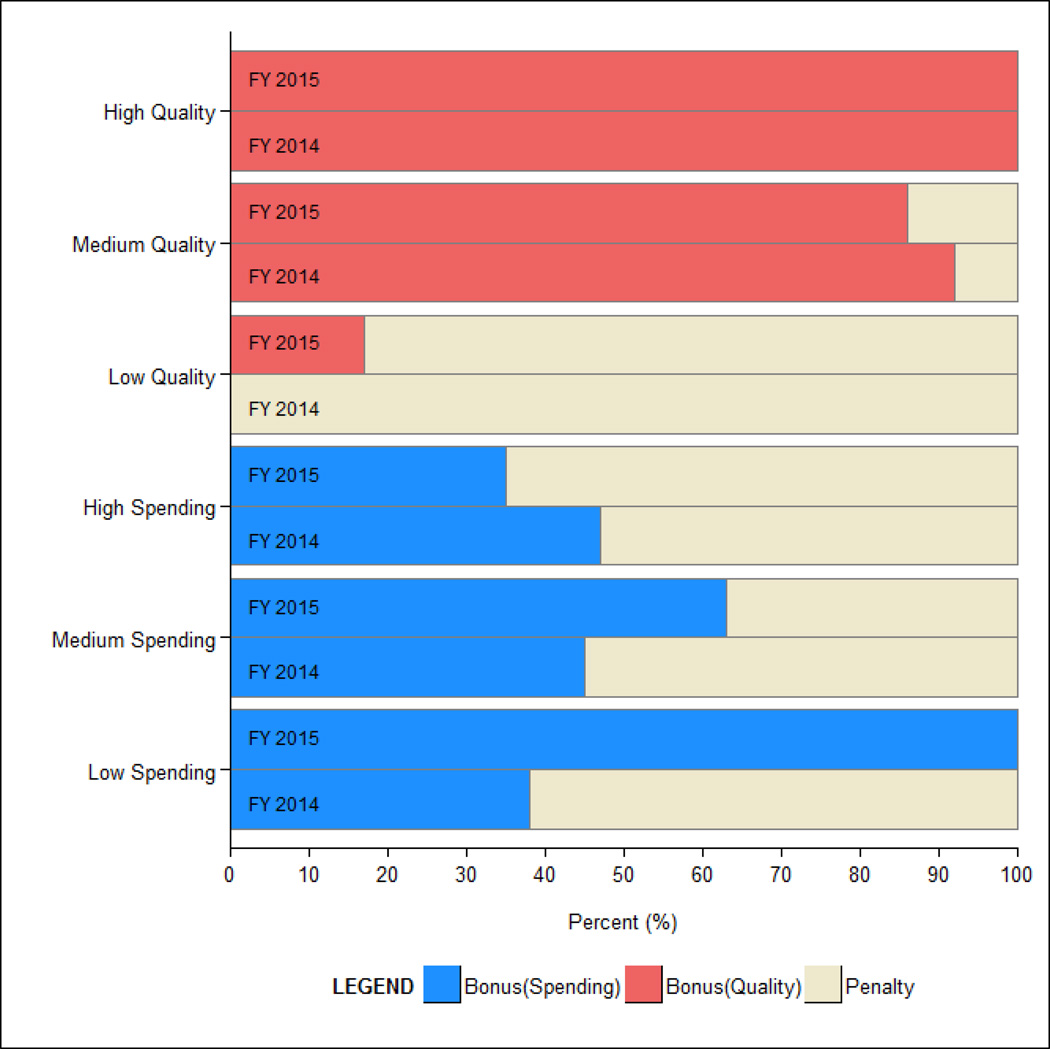

We found that there were large differences in the probability of low-spending hospitals receiving bonuses and penalties between FY 2014 and FY 2015 (Exhibit 3). For example, in FY 2014 prior to the addition of a spending measure, only 38% of 32 low-spending hospitals received a bonus in the program, while all 68 low-spending hospitals received bonuses in FY 2015. With the addition of the spending measure, medium-spending hospitals had a substantial increase in their probability of receiving a bonus (45% of 1,228 hospitals in FY 2014 vs. 63% of 1,473 hospitals in FY 2015), while high-spending hospitals had a lower likelihood of receiving bonuses (47% of 1,419 hospitals in FY 2014 vs. 35% of 1,138 hospitals in FY 2015).

EXHIBIT 3.

Proportion of Hospitals Receiving Bonuses or Penalties in FY 2014 and FY 2015 by Spending Category and Quality Category in Each Year

SOURCE/NOTES: SOURCE – Authors’ analysis of Fiscal Years 2014 & 2015 data from CMS Impact File and Hospital Compare. NOTES - All p<0.001, except for High Quality.

With the addition of a spending measure and the corresponding decrease in weight applied to quality measures, hospital quality became a less uniform predictor of bonuses and penalties. All high-quality hospitals received bonuses in both years of our analysis (Exhibit 3). However, while no low quality hospitals received a bonus in FY 2014, 17% of 1,339 low-quality hospitals (231 hospitals) received a bonus in FY 2015 (p-value <0.001). Among hospitals that received a bonus in FY 2015, there were significant differences in quality of care. The low-quality hospitals that received bonuses performed significantly worse on almost all measures of quality compared to the medium- and high-quality hospitals (online Appendix Exhibit A6).16 In sensitivity analyses with a more restrictive definition of low quality, we found that low quality hospitals were still more likely to receive bonuses in FY 2015 compared to FY 2014 (Online Appendix Exhibit A7).16

Evaluating the magnitude of the bonuses and penalties received by hospitals in FY 2015, we find that the best performers in the program (low-spending or high-quality) had the largest bonuses (0.75% and 0.94%, respectively) (Exhibit 4). These values represent the increase or decrease in a hospitals’ base-DRG amount. For the 231 hospitals that were low-quality and received a bonus in FY 2015, their average bonus was 0.18%, while for the other low-quality hospitals, their penalty was on average −0.33%. All average bonus and penalty amounts were significantly different across spending or quality categories. The seven hospitals that were both low-spending and high-quality in FY 2015 had bonuses ranging from 1.40% to 1.77%.

Exhibit 4.

Average Hospital Bonus and Penalty Awarded in FY 2015, by Performance Category

| Type of Incentive | Best | Medium | Worst | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Spending |

High Quality |

Medium Spending |

Medium Quality |

High Spending |

Low Quality |

|

| Bonus, % change in Medicare payments |

+0.75 | +0.94 | +0.39 | +0.34 | +0.24 | +0.18 |

| Penalty, % change in Medicare payments |

0 | 0 | −0.26 | −0.06 | −0.31 | −0.33 |

SOURCE – Authors’ analysis of Fiscal Years 2014 & 2015 data from CMS Impact File and Hospital Compare. NOTES - For example, on average, in FY 2015, low-quality hospitals awarded a bonus received a 0.18% increase in their base-operating DRG payment for each Medicare discharge. Low-quality hospitals that were penalized received a 0.33% decrease in their base-operating DRG payment for each Medicare discharge. Both the bonuses and penalties in this table are significantly different (p<0.001) when compared across either spending or quality categories.

Discussion And Conclusion

We found that larger, for-profit, urban, or major teaching hospitals were more likely to have high episode spending. Because of this, the addition of a spending measure to HVBP increased the likelihood that such hospitals would receive penalties. Overall, hospital quality had a weak and inconsistent association with spending. For this reason, adding a spending measure to the program as currently designed increased the probability that both low-spending and low-quality hospitals would receive bonuses.

Our analysis is one of the first to evaluate the effects of rewarding both quality and spending in a nationwide pay-for-performance program. Prior work has examined what types of providers have gained or lost in large-scale pay-for-performance programs focused on quality.17,18 Others have examined whether or not pay-for-performance incentives have improved quality.19–25 We extend this research and find that in a major new effort to reward both high quality and low spending, there are a different set of winners and losers. The consequences of this redistribution of penalties and bonuses are still unknown.

Our results reflect both the relationship between quality and episode-spending, as well as program design. We found that the overall correlation between quality and episode spending was low. High-spending hospitals, which tended to be larger, performed modestly better on clinical process of care measures; while low-spending hospitals fared better in the patient experience of care domain. Our findings align with previous research that demonstrates that larger hospitals do better on clinical processes of care, while smaller hospitals do better on patient experience measures.26,27 Adding the Medicare Spending per Beneficiary measure and decreasing the overall relative weight of quality measures changed the types of hospitals that earned bonuses far more than if CMS had included another measure that was highly correlated with current quality measures.

While the weak relationship between hospital quality and episode spending contributed to low-quality hospitals receiving bonuses, program design was another necessary factor. HVBP requires no minimum performance threshold for receiving a bonus, so low-quality hospitals could improve their probability of receiving a bonus with low-spending. The effects of the addition of a new spending measure and the subsequent decrease in the weight placed on quality were mitigated by the size of the bonus, with low quality hospitals on average receiving smaller bonuses than high quality hospitals.

Our results demonstrate that CMS’ effort to reward both high quality and low spending in the HVBP program has changed the distribution of bonuses and penalties awarded to many US hospitals. High-quality, low-spending hospitals received the greatest financial benefit from the program. In this respect, CMS achieved its goal with the new spending measure: “to identify hospitals involved in the provision of high quality care at a lower cost to Medicare.”6 On the other hand, some low-quality hospitals received bonuses because of their lower spending. The bonuses given to low-quality hospitals are concerning. Other CMS programs offer viable solutions to address this concern. In the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier (PVBPM) program’s “quality-tiering approach,” incentives are based on a cross-tabulation of provider performance on cost and quality. Low-quality providers are not eligible for bonuses, regardless of spending performance. Similarly, high-cost providers are not eligible for bonuses, regardless of quality performance.28 In the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), accountable care organizations (ACOs) must meet both quality performance standards along with expenditure benchmarks in order to receive a share of savings.29 If the relationship between HVBP quality and spending measures continues to be weak and inconsistent, adopting either of these approaches would eliminate rewards to low quality hospitals and limit incentives hospitals currently have to trade off reductions in spending for improvements in quality. If CMS chooses to incorporate a minimum quality threshold for bonuses, it might also consider whether or not it would be beneficial to establish a separate threshold for each of the three HVBP quality domains.

In summary, we find that adding a measure of spending to the HVBP program and decreasing the overall weight of quality has changed the types of hospitals receiving bonuses or penalties. Although the program rewards the best performers appropriately, some hospitals receive bonuses despite their low quality. CMS should consider adding a minimum quality threshold to avoid rewarding low-quality hospitals that are also low-spending.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals--HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Jul 15]. Hospital value-based purchasing 2014 [Internet] Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html?redirect=/Hospital-Value-Based-Purchasing/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Jul 15]. Frequently asked questions hospital value-based purchasing program [Internet] Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/downloads/HVBPFAQ022812.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111–148, 124 Stat. 353, Sec. 3001. 2010 Mar 23; [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway P. CMS releases data on quality to help patients choose providers [Internet] [cited 2015, Jul 15];The CMS Blog. 2014 Available from: http://blog.cms.gov/2014/12/18/cms-releases-data-on-quality-to-help-patients-choose-providers/

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long-term care hospital prospective payment system and fiscal year 2013 rates; hospitals' resident caps for graduate medical education payment purposes; quality reporting requirements for specific providers and for ambulatory surgical centers; final rule. Fed Regist. 2012;77(170):53257–53750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Jul 15]. National provider call: hospital value-based purchasing [Internet] Available from: https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/outreach/npc/downloads/hospvbp_fy15_npc_final_03052013_508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.QualityNet. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Jun 30]. Medicare spending per beneficiary (MSPB) measure overview [Internet] Available from: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier3&cid=1228772053996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasaitis L, Fisher ES, Skinner JS, Chandra A. Hospital quality and intensity of spending: is there an association? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w566–w572. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Dobson A, Book RA, Epstein AM. Measuring efficiency: the association of hospital costs and quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):897–906. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussey PS, Wertheimer S, Mehrotra A. The association between health care quality and cost: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):27–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2013 Jun 30]. Hospital value-based purchasing program fact sheet 2013 [Internet] Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/Hospital_VBPurchasing_Fact_Sheet_ICN907664.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.QualityNet. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Jul 1]. MSPB measure information form 2015 [Internet] Available from: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228890455405&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DMSPB_MeasInfoForm_May2015.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Editor, please insert appendix verbiage.

- 17.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the hospital readmissions reduction program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.94856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajaram R, Chung JW, Kinnier CV, Barnard C, Mohanty S, Pavey ES, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with penalties in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services hospital-acquired condition reduction program. JAMA. 2015;314(4):375–383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. The effect of financial incentives on hospitals that serve poor patients. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(5):299–306. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-5-201009070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, Rothberg MB, Benjamin EM, Ma A, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):486–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glickman SW, Ou FS, DeLong ER, Roe MT, Lytle BL, Mulgund J, et al. Pay for performance, quality of care, and outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297(21):2373–2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristensen SR, Meacock R, Turner AJ, Boaden R, McDonald R, Roland M, et al. Long-term effect of hospital pay for performance on mortality in England. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(6):540–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Polsky D. The effect of pay-for-performance in nursing homes: evidence from state Medicaid programs. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(4):1393–1414. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jha AK, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. The long-term effect of premier pay for performance on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1606–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1112351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan AM, Burgess JF, Jr, Pesko MF, Borden WB, Dimick JB. The early effects of Medicare's mandatory hospital pay-for-performance program. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):81–97. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehrman WG, Elliott MN, Goldstein E, Beckett MK, Klein DJ, Giordano LA. Characteristics of hospitals demonstrating superior performance in patient experience and clinical process measures of care. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(1):38–55. doi: 10.1177/1077558709341323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliott MN, Cohea CW, Lehrman WG, Goldstein EH, Cleary PD, Giordano LA, et al. Accelerating improvement and narrowing gaps: trends in patients' experiences with hospital care reflected in HCAHPS public reporting. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1850–1867. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2015 Jul 10]. Summary of 2015 physician value-based payment modifier policies [Internet] Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeedbackProgram/Downloads/CY2015ValueModifierPolicies.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyarsky V, Parke R. The Medicare shared savings program and the pioneer accountable care organizations [Internet] [cited 2015 Jul 10];Milliman Healthcare Reform Briefing Paper. 2012 May; Available from: http://us.milliman.com/insight/healthreform/The-Medicare-Shared-Savings-Program-and-the-Pioneer-Accountable-Care-Organizations/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.