Abstract

Rationale: The incidence and risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to the intensive care unit (ICU) experience have not been reported in a mixed veteran and civilian cohort.

Objectives: To describe the incidence and risk factors for ICU-related PTSD in veterans and civilians.

Methods: This is a prospective, observational, multicenter cohort enrolling adult survivors of critical illness after respiratory failure and/or shock from three Veterans Affairs and one civilian hospital. After classifying those with/without preexisting PTSD (i.e., PTSD before hospitalization), we then assessed all subjects for ICU-related PTSD at 3 and 12 months post hospitalization.

Measurements and Main Results: Of 255 survivors, 181 and 160 subjects were assessed for ICU-related PTSD at 3- and 12-month follow-up, respectively. A high probability of ICU-related PTSD was found in up to 10% of patients at either follow-up time point, whether assessed by PTSD Checklist Event-Specific Version (score ≥ 50) or item mapping using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV). In the multivariable regression, preexisting PTSD was independently associated with ICU-related PTSD at both 3 and 12 months (P < 0.001), as was preexisting depression (P < 0.03), but veteran status was not a consistent independent risk factor for ICU-related PTSD (3-month P = 0.01, 12-month P = 0.48).

Conclusions: This study found around 1 in 10 ICU survivors experienced ICU-related PTSD (i.e., PTSD anchored to their critical illness) in the year after hospitalization. Preexisting PTSD and depression were strongly associated with ICU-related PTSD.

Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder, intensive care unit, veterans

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can occur in patients after the traumatizing events in the intensive care unit (ICU), but the specific epidemiology of ICU-related PTSD remains unclear, with wide-ranging estimates of 1-year prevalence rates. Furthermore, preexisting PTSD has rarely been systematically assessed in prior cohorts, which parallels the infrequent reporting and assumption of ICU-related PTSD incidence. Civilian populations have dominated the literature of PTSD after critical illness (i.e., as opposed to inclusion of the expanding and aging veteran population), and post-ICU PTSD determinations have been primarily based on single screening instruments neither anchored to the critical illness nor mapped to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This multicenter, prospective cohort study, which assessed preexisting PTSD and included veterans and civilians from mixed medical and surgical ICU populations, demonstrated that around 1 in 10 survivors experienced ICU-related PTSD (i.e., PTSD anchored to their critical illness) in the year after hospitalization. Preexisting PTSD and depression are strong markers for ICU-related PTSD risk, and healthcare providers caring for these patients should be cognizant of the possible presence of this condition.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is defined as persistent difficulty processing previously experienced extreme life-threatening situations, such as combat violence, natural disasters, assault, or critical illness. An individual with PTSD may reexperience the traumatic event through persistent memories, nightmares, or flashbacks (intrusion); may try to avoid reminders of the event and demonstrate emotional “numbness” (avoidance); and/or may have sleeplessness, anger, hypervigilance, and an exaggerated response to startling events (hyperarousal) (1). Survivors of critical illness have reported PTSD symptoms months to even years after critical illness, possibly related to nightmare-like experiences, safety restraints creating communication barriers, and protective mechanical ventilation causing feelings of breathlessness and fear of imminent death (2, 3). Preexisting psychiatric problems, including depression and prior PTSD, have a strong potential to exacerbate intensive care unit (ICU)-related PTSD (i.e., PTSD symptoms anchored to the ICU experience), but the detailed assessment of prior PTSD is rarely done (4, 5), and prior PTSD remains unmeasured in many mixed-population ICU studies (1, 6–8).

Studies assessing for the risk of PTSD after critical illness have reported prevalence rates ranging from 0 to 64%, depending on the population and intervention studied, the time interval between the ICU admission and assessment, and the instrument for screening or diagnosis used (e.g., Impact of Event Scale, Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome screening tool, Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, PTSD Checklist Event-Specific Version [PCL-S]) (4, 5, 9–11). Most prior studies have used PTSD screening instruments rather than diagnostic instruments and have seldom mapped symptoms to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which can be done using the PCL-S (6, 10–12). Even among current era studies, a 2015 metaanalysis of more than 500 ICU patients reported a 22% pooled PTSD prevalence at 1 year (11), which contrasts with our recently published large civilian ICU cohort showing a threefold lower PTSD prevalence of 7% at 1 year using the PCL-S instrument with DSM-IV mapping (13). Additionally, no multicenter studies have concurrently enrolled veteran and civilian patients during their critical illness, systematically evaluated them for preexisting PTSD and traumatic life events, and followed them longitudinally to evaluate the incidence and unique risk factors for ICU-related PTSD in these potentially very different populations.

In this study using the PCL-S instrument and DSM mapping, we describe the incidence of ICU-related PTSD risk and its underlying symptom clusters of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal among veterans and civilians who had survived a critical illness. We also examine the potential preexisting (e.g., age, prior depression, prior PTSD) and hospital (e.g., severity of illness, delirium, analgosedative exposure) risk factors for ICU-related PTSD. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of a published abstract (14) and unpublished distributed abstracts (15–17).

Methods

The study methods are detailed in the online supplement.

Institutional Review Board Approval

The Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors (BRAIN-ICU, NCT00392795) and Measuring the Incidence and Determining Risk Factors for Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors (MIND-ICU, NCT00400062) studies obtained ethics approval from the Vanderbilt University Human Research Protection Program (institutional review board numbers 060593 and 040542). Participants and/or legally authorized representatives (i.e., surrogates) gave informed consent before taking part.

Study Design, Population, and Patients

This prospective, observational, multicenter cohort study was nested within two studies with identical eligibility criteria (e.g., inclusion of those with respiratory failure and/or shock). Veteran patients were enrolled in the MIND-ICU study, and civilian patients were enrolled in the BRAIN-ICU study (18). To be included into this nested PTSD cohort study, patients were required to complete preexisting PTSD assessments (see Figure E1 in the online supplement), which were incorporated into the parent cohorts from February 15, 2009 onward. Although the overall prevalence rates and risk factors of PTSD from the BRAIN ICU (civilian patients) study have already been published (13), this cohort is unique and substantially improves on prior reports in three ways: the cohort comprises veteran patients (MIND-ICU) and civilian patients (BRAIN-ICU), allowing comparisons; the cohort used had an enhanced and rigorous assessment for preexisting PTSD as described below; and the cohort uses PCL-S threshold and DSM mapping methods to ascertain the incidence of ICU-related PTSD. Informed consent was obtained from patients or their healthcare proxy. If consent was initially obtained from a healthcare proxy, the patient provided informed consent when deemed competent.

Preexisting PTSD Assessments

Preexisting PTSD was used as another demographic characteristic for this cohort and potential risk factor for ICU-related PTSD but did not exclude subjects from this study. Before hospital discharge, we screened patients for preexisting PTSD (Figure E1). When patients reported a previous history or diagnosis of PTSD, we identified the traumatic event and then confirmed the probability of ongoing sequelae due to that prior traumatic event with the PCL-S (19). We categorized patients with a PCL-S score of 50 or greater as having a high probability of preexisting PTSD (i.e., PTSD before the ICU) (13, 20).

Patients with no prior diagnosis of PTSD were asked about their prior exposure to traumatic stressors using a modified Traumatic Life Event Questionnaire (TLEQ) (21, 22). Patients who reported one or more traumatic stressors on the modified TLEQ (score ≥ 1) were also evaluated with the PCL-S anchored around the most significant traumatic event; those with PCL-S scores of 50 or greater had high probability of preexisting PTSD.

PTSD Assessments Associated with Critical Illness (ICU-related PTSD)

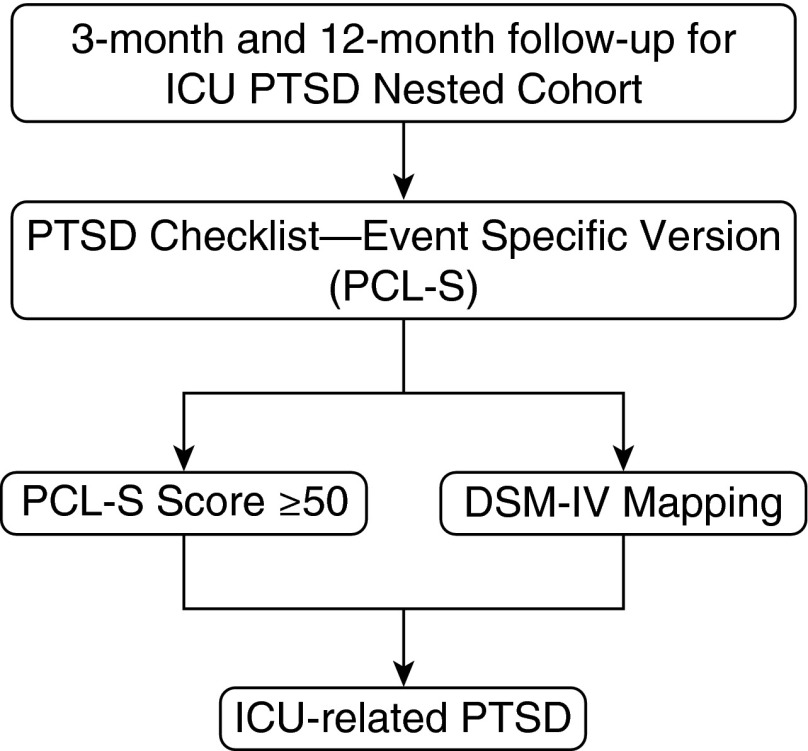

At 3 and 12 months after hospital discharge, we used the PCL-S anchored to the ICU experience as the traumatic event to evaluate survivors for new PTSD related to their ICU stay (Figure 1). We categorized patients as having a high probability of PTSD using two methods: a cut-off–based threshold approach relying on PCL-S score of 50 or greater and an item-mapping approach based on DSM-IV criteria (13, 23).

Figure 1.

Assessment of intensive care unit (ICU)-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). At 3 and 12 months after hospital discharge, we used the PTSD Checklist Event-Specific Version (PCL-S) anchored to the ICU experience as the traumatic event to evaluate survivors for new PTSD related to their ICU stay. We categorized patients as having a high probability of PTSD using two methods: a cut-off–based approach relying on PCL-S score of 50 or greater and an item-mapping approach based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) criteria (13, 22).

Statistical Analysis

We present continuous data as medians (interquartile ranges) and categorical variables as percentages. To assess the relationships of baseline and in-hospital characteristics with ICU-related PTSD, we used a proportional odds logistic regression model with the PCL-S scores as the continuous outcome for each time point. The following risk factors were included: age at enrollment, sex, preexisting PTSD, preexisting depression, short Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly score, mean daily modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, delirium duration, mean daily dose of benzodiazepines in the ICU, mean daily dose of opiates in the ICU, and veteran status. To minimize bias in multivariable models due to missingness in covariates or outcomes, we included in our main analysis all patients who survived and remained in the study at each time point, using multiple imputation to account for missing data (24). Imputation of ICU-related PCL-S scores was required in 31 of 212 (15%) subjects at 3 months and in 27 of 187 (14%) subjects at 12 months. We used R version 3.1.2 for all analyses. We used the lrm function from the rms package (version 3.14-6) for proportional odds logistic regression, in conjunction with the aregImpute and fit.mult.impute functions from the Hmisc package (0.9-5) for multiple imputation.

Results

ICU Cohort Enrollment

We enrolled 255 survivors of critical illness in this study, including 72 veteran patients and 183 civilian patients, between February 15, 2009 and March 27, 2010 (Table 1). Between enrollment and 3-month follow-up, 29 patients (11%) died and 14 (5%) withdrew from the study, leaving 212 patients eligible for the 3-month ICU-related PTSD assessments. Between 3- and 12-month follow-ups, an additional 23 subjects (11% of 3-month survivors) died and 2 (1%) withdrew, leaving 187 patients eligible for the 12-month ICU-related PTSD assessments. The 16 patients who withdrew were similar to those who did not withdraw with respect to demographics (e.g., age, sex, severity of disease, length of ICU stay, history of depression).

Table 1.

Enrollment and Follow-up for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Intensive Care Unit Survivor Cohort

| Veteran | Civilian | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital survivors in PTSD cohort, n | 72 | 183 | 255 |

| Died between discharge and 3 mo | 8 (11) | 21 (11) | 29 (11) |

| Withdrew between discharge and 3 mo | 1 (1) | 13 (7) | 14 (5) |

| Available for PTSD assessment, 3 mo | 63 (88) | 149 (81) | 212 (83) |

| Died between 3 and 12 mo | 11 (17) | 12 (8) | 23 (11) |

| Withdrew between 3 and 12 mo | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Available for PTSD assessment, 12 mo | 51 (81) | 136 (91) | 187 (88) |

Definition of abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise noted. Veteran indicates Veterans Affairs ICU survivors; Civilian indicates civilian ICU survivors.

Baseline ICU Cohort Characteristics

Among the 212 survivors eligible for follow-up, the veteran and civilian group characteristics differed slightly, as shown in Table 2. Compared with civilian participants, veterans tended to be older but had lower severity of illness. Delirium was common in both groups but slightly less common among veterans. Among those with delirium, the median duration of delirium was 3 (1–6) days. Preexisting PTSD history or trauma exposure information was obtained from 178 (84%) of the 212 survivors; 21 (12%) of these self-reported a preexisting PTSD diagnosis, 149 patients had a TLEQ score of 1 or more, and 8 had no traumatic life events per the TLEQ. Among the 170 patients with a history of PTSD or traumatic exposure (TLEQ score ≥ 1), 168 completed the PCL-S, and 17 (10%; 7 veterans, 10 civilians) met criteria for high probability of preexisting PTSD based on a PCL-S score of 50 or greater. No patient with preexisting PTSD identified warfare or life-threatening illness as his or her main prior traumatic event. No patient who withdrew met criteria for high probability of preexisting PTSD.

Table 2.

Baseline and In-Hospital Characteristics for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Cohort Eligible for 3-Month Follow-up

| Veteran (n = 63) | Civilian (n = 149) | Overall (N = 212) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age at enrollment, yr | 64.6 (61.3–73.7) | 56.6 (46.4–65.2) | 60.9 (50.0–68.2) |

| Race, white | 58 (92) | 128 (86) | 186 (88) |

| Sex, male | 58 (92) | 78 (52) | 136 (64) |

| IQCODE at enrollment | 3.06 (3.00–3.19) | 3.00 (3.00–3.12) | 3.00 (3.00–3.12) |

| Depression history | 20 (32) | 58 (39) | 78 (37) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| ICU type | |||

| Medical | 48 (76) | 73 (49) | 121 (57) |

| Surgical | 15 (24) | 76 (51) | 91 (43) |

| APACHE II at ICU admission | 17.0 (12.5–22.0) | 24.0 (17.0–30.0) | 21.0 (16.0–27.2) |

| Preexisting PTSD | 7 (15) | 10 (8) | 17 (10) |

| In-hospital characteristics | |||

| Mean ICU modified SOFA | 4.3 (3.4–6.0) | 5.4 (4.3–7.4) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) |

| Delirium | 36 (57) | 110 (74) | 146 (69) |

| ICU length of stay | 4.4 (2.2–6.9) | 4.0 (1.9–10.0) | 4.2 (1.9–9.7) |

| Hospital length of stay | 9.1 (6.6–13.2) | 9.0 (6.0–17.1) | 9.1 (6.0–16.2) |

| Benzodiazepine exposure | 35 (56) | 106 (71) | 141 (67) |

| Opiates exposure | 43 (68) | 132 (89) | 175 (83) |

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ICU = intensive care unit; IQCODE = short Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; modified SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score excluding the Glasgow Coma Scale score component; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%).

ICU-related PTSD Incidence and Symptom Clusters

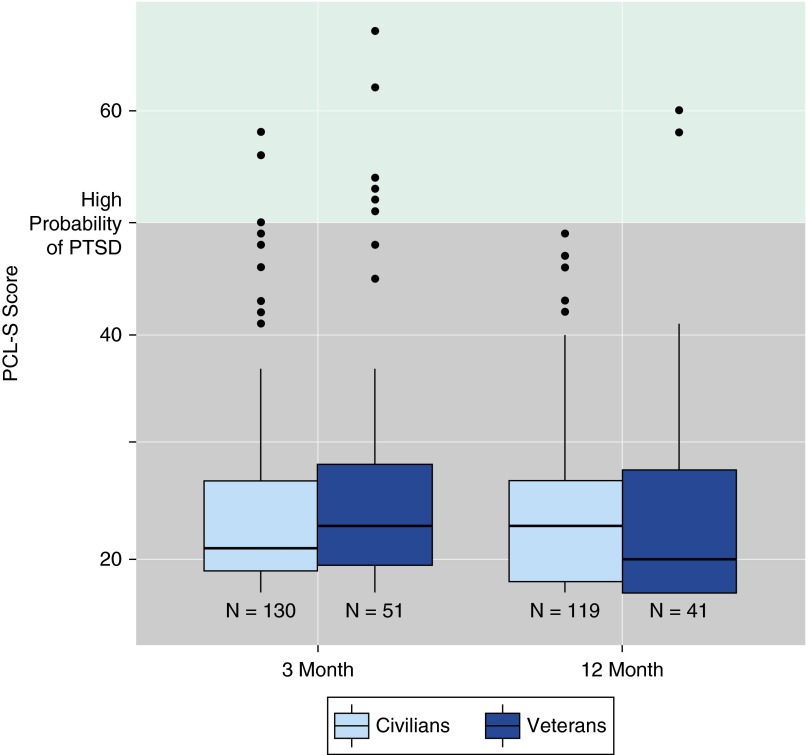

Of the 212 patients who were alive and still in the study at 3-month follow-up, 181 completed the ICU-related PTSD assessment, with a median PCL-S score of 22 (19–28); the median scores were 23 (20–28) among veterans and 21 (19–27) among the civilian patients (Table 3, Figure 2). Similarly, among 187 who were alive and still in the study at 12 months, 160 completed ICU-related PTSD assessment, with a median PCL-S score of 22 (18–28); median scores were 20 (17–28) among veterans and 23 (18–27) among the civilian patients (Table 3, Figure 2). In general, up to 10% had a high probability of ICU-related PTSD, whether assessed by PCL-S score or DSM-IV mapping, at either follow-up time point (Table 3). Of the 194 subjects assessed at 3 and/or 12 months, the cumulative incidence of ICU-related PTSD over 12 months was 6% (11 of 194) based on PCL-S scores of 50 or greater and 12% (23 of 194) based on DSM-IV PTSD criteria. PTSD symptom clusters of avoidance and hyperarousal were observed in 40% of our patients at both time points (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intensive Care Unit–related Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Incidence and Symptom Clusters

| 3 Months after Hospitalization | 12 Months after Hospitalization | |

|---|---|---|

| PCL-S score, median (IQR) | 22 (19-28) | 22 (18-28) |

| ICU-related PTSD incidence, n (%) | ||

| By PCL-S score ≥ 50 | 10 (6) | 2 (1) |

| By DSM-IV mapping | 15 (8) | 10 (6) |

| ICU-related PTSD symptom clusters, n (%) | ||

| Intrusion | 25 (14) | 25 (16) |

| Avoidance | 78 (43) | 60 (38) |

| Hyperarousal | 82 (45) | 71 (44) |

| No ICU-related PTSD symptom clusters, n (%) | ||

| No intrusion, no avoidance, no hyperarousal | 69 (38) | 74 (46) |

Definition of abbreviations: DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; PCL-S score = PTSD Checklist Event-Specific version; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise noted. At 3 and 12 months after hospitalization, 181 and 160 subjects were assessable, respectively.

Figure 2.

Intensive care unit (ICU)-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (i.e., PTSD symptoms related to the ICU experience) at 3- and 12-month follow-up. The box-and-whisker plots show the PTSD Checklist Event-Specific version (PCL-S) score related to the ICU experience at 3 months and 12 months separately for the civilian and veteran populations. The horizontal line within each box indicates the median PCL-S score, the upper and lower limits of the boxes indicate the 25th to 75th interquartile range, the ends of the vertical whiskers indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the black dots indicate values outside these ranges. A score of 50 or greater on the PCL-S denotes high probability of ICU-related PTSD.

Risk Factors for ICU-related PTSD

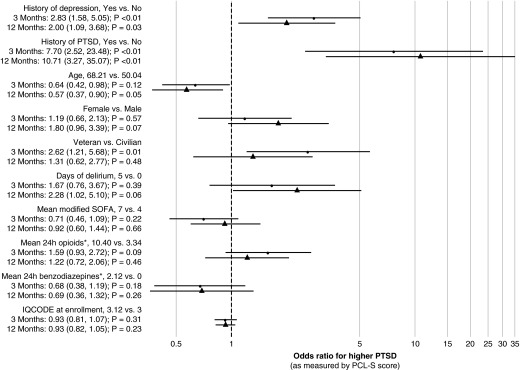

After adjusting for covariates, at both 3 and 12 months, preexisting PTSD was independently associated with higher odds of greater PCL-S scores (3-month odds ratio [OR], 7.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5–23.5; P < 0.001; 12-month OR, 10.7; 95% CI, 3.3–35.1; P < 0.001), as was preexisting depression (3-month OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.6–5.1; P < 0.001; 12-month OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.1–3.7; P = 0.03) (Figure 3). Delirium duration was not significantly associated with greater PCL-S scores at either 3 or 12 months. Although being a veteran ICU survivor was a risk factor for ICU-related PTSD at 3 months (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2–5.7; P = 0.01), it was not a risk factor at 12 months after accounting for other confounders (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.6–2.8; P = 0.48) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk factors for intensive care unit–related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at 3- and 12-month follow-up. This forest plot denotes the association between risk factors of interest and the odds of having a higher PTSD Checklist Event-Specific version (PCL-S) score at 3 and 12 months. For each risk factor, the point estimate and 95% confidence interval (CI) are shown. Interpretative example: at both 3 and 12 months, preexisting PTSD was independently associated with higher odds of greater PCL-S scores (3-month odds ratio [OR], 7.7; 95% CI, 2.5–23.5; P < 0.001; 12-month OR, 10.7; 95% CI, 3.3–35.1; P < 0.001) as compared with a patient without preexisting PTSD. IQCODE = short Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; SOFA = modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score excluding the Glasgow Coma Scale score component. *Benzodiazepine and opiate doses were cube-root transformed to reduce the influence of extreme outliers.

Discussion

Our investigation was the first to rely on validated methods to identify ICU-related PTSD incidence in a multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study of veteran and civilian survivors of critical illness. We demonstrated that the cumulative incidence of PTSD associated with the ICU experience was 6 to 12% in the year after hospital discharge and that approximately two in five ICU survivors developed clinically significant PTSD symptoms of avoidance or hyperarousal, which both occurred twice as frequently as intrusion symptoms. This study found preexisting PTSD and depression were both strongly associated with ICU-related PTSD, whereas no association was detected between PTSD risk and duration of delirium, opiate dose, or benzodiazepine dose. Veterans were not consistently at a higher risk of developing ICU-related PTSD.

A major strength of this study was our multicenter cohort design that included both veteran and civilian participants from mixed medical and surgical ICU populations. Additionally, we used a rigorous approach to identify preexisting PTSD. First, we asked patients about a prior diagnosis of PTSD. Second, we evaluated patients who did not carry a formal diagnosis for exposure to traumatic events and assessed which of those experiences were most stressful. Third, we further tested those with a prior diagnosis of PTSD or exposure to traumatic life events with the PCL-S anchored to the greatest prior traumatic event to ascertain whether they had a high probability of preexisting PTSD. Even though some patients had a life-threatening illness in the past, none of the patients with preexisting PTSD identified critical illness as their stressor. This enabled us to determine the incidence of ICU-related PTSD, which we accomplished using two methods: the established cutoff approach to the PCL-S and DSM-IV mapping of PTSD criteria.

Our results demonstrate the cumulative incidence of ICU-related PTSD risk at 1 year to be in the 10% range, which is similar to some previously published prevalence rates (4, 13, 25) and incidence rates (4, 5) and extends those findings to include veterans who survive a critical illness. In contrast, our observed incidence rates of PTSD risk at 3 and 12 months are lower than those of other reported prevalence rates of up to 64% (9–11). Many of these prior studies used brief screening questionnaires or clinician diagnosis (10), sought to identify PTSD without attempting to anchor it explicitly to critical illness, and did not use DSM-IV mapping of PTSD symptoms. Our study is similar in size to the largest post-ICU PTSD studies that have demonstrated a similar point prevalence of 8 to 9% and incidence of 9 to 13% based on follow-up times of 3 months or less (4, 5, 25). Other post-ICU PTSD studies with a follow-up time of at least 12 months have reported wider prevalence ranges but included fewer than 100 subjects (26–32). No study has used detailed self-report assessments for prior PTSD among enrolled veterans; thus, our study is the first to report PTSD incidence related to the ICU experience in a cohort of both veteran and civilian patients. To put our results in perspective, the definitive National Comorbidity Survey Replication used DSM-IV criteria to determine the 12-month prevalence of PTSD among the general U.S. adult population and found that only 3.5% had PTSD (33), which is about one-third of our cumulative incidence rate in patients 12 months after a critical illness. Thus, despite lower rates of PTSD related to critical illness in our cohort, the rates we observed are still significantly greater than the population at large.

Although the PTSD symptom clusters of intrusion and avoidance have been found in survivors up to 1 year after critical illness, these have been quantified using elements of the Impact of Event Scale and Davidson Trauma Scale in small populations with limited follow-up rather than using DSM-IV criteria (11, 34). In our combined veteran and civilian cohort, we mapped each of the three PTSD symptom clusters based on DSM-IV criteria and only considered a symptom positive if a patient had a score on any of the corresponding questions of 3 or more, which reflects clinically significant impairments. Almost half of our patients had hyperarousal and avoidance symptoms, with a lower but substantial proportion of 20% exhibiting intrusion symptoms. Although we did not explore these intrusive symptoms, these repeatedly experienced memories in ICU survivors have been reported to be hallucinatory or delusional (i.e., consistent with ICU psychosis) rather than reality based and linked to classic PTSD (35). A weakness of our symptom cluster determination is its basis on a three-factor DSM-IV–based model; we did not examine four- or five-factor PTSD models that incorporate the dimensions of dysphoria and anxious arousal (36).

In contrast to older studies (25, 37, 38) but in line with recent studies (11), we found that benzodiazepine dose had no association with ICU-related PTSD after adjusting for severity of illness, preexisting depression, preexisting PTSD, and other risk factors. Although more than 65% of our ICU patients received a benzodiazepine, the total exposure by dose was small (6.3 mg median 24-h dose) and may have resulted in a lack of variance. There have been additional pharmacologic associations with exogenous hydrocortisone (39), the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (40), and lower PTSD rates, but we did not quantify this medication class or the associated genetic polymorphisms in our study (41). In concordance with prior work, systematic reviews, and metaanalyses (6, 10–12), we found that sex and severity of illness did not influence outcomes, whereas a history of depression was strongly associated with ICU-related PTSD. Aligning with our group’s prior work (13, 37) and with another well-done long-term study of survivors of acute lung injury (32), delirium duration did not affect ICU-related PTSD in this mixed cohort composed of veterans and civilians.

Patients, families, coworkers, outpatient mental health practitioners, and primary care providers should be vigilant about the possibility of PTSD and the prominent constellation of avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms after critical illness. We want the readership to be clear that these ICU-related PTSD symptom clusters are truly problematic signs and not measurement artifact, although they represent a forme fruste of PTSD, rather than full-blown PTSD. As compared with other PTSD symptoms, avoidance is associated with functional impairment and disability after a medical illness, as patients often ignore significant subsequent health demands given they are reminders of the inciting medical event. For example, PTSD anchored to an initial myocardial infarction results in nonadherence to cardiac medications (42). PTSD treatment strategies targeting avoidance symptoms, such as prolonged exposure and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, may need to be considered for the ICU survivor (43). For those patients with PTSD-related hyperarousal, pharmacologic antidepressants targeting norepinephrine reuptake inhibition may induce anxiolysis, calm the sympathetic nervous system, and limit future cardiovascular consequences (44). It is possible that antipsychotics, particularly of the atypical classes, may decrease rates of intrusion (45). Although PTSD may not represent a very frequent psychological consequence after a critical illness, a history of PTSD and depression are strong markers for ICU-related PTSD risk, and healthcare providers caring for these patients should be cognizant about the possible presence of this condition.

A similar PTSD prevalence of 8% exists in current and former service members deployed to the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, steering the U.S. Department of Defense and VA hospitals to construct numerous screening, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation programs to address this condition (46). The civilian sector, on the other hand, has no coordinated PTSD strategy for the 5 million annual survivors of critical care illness. Currently, the international psychological aftercare for ICU survivors is not organized proactively; rather, it is largely reactive in response to disabling reports from survivors, caregivers, and primary care providers. The Institute of Medicine in the United States has recommended a systematic collection, analysis, and dissemination of data assessing the quality of postconflict PTSD care in the military and veteran populations (47). We suggest that the same should apply to the large civilian and veteran populations of critically ill survivors.

Our study had many strengths, as outlined earlier, but it also has some limitations. One major limitation is that our measurement of preexisting PTSD during the hospital phase may have been contaminated by current psychological distress and early ICU-related acute stress phenomena. We do not know if our preexisting PTSD assessments are robust to such post-ICU reporting biases. This study limitation could be partly conquered in future work on elective surgical populations, where preexisting PTSD could be properly measured before the acute hospitalization and ICU stay. We do note the small number of patient withdrawals uniquely lacked preexisting PTSD, perhaps speaking to their implicit bias against further follow-up and evaluation for ICU-related PTSD. Another study limitation is that one of our PTSD determinations was DSM-IV based, as study inception occurred before the interim two-decade revision, the DSM-5 (48), which now makes no differentiation between acute and chronic PTSD when symptoms last at least 1 month. It is important to note both of our PTSD measurements related to PTSD risk, not PTSD diagnosis (49–51). Furthermore, as is the case with most observational studies, no claims of causality can be made. Finally, although we included as many variables as possible (without overfitting our models) that we believed to have strong scientific evidence as risk factors, it is possible that we did not account for all confounders; for example, PTSD genetic markers (41, 52), veteran deployment classification (53), or ICU steroid usage (39) could have a potentially confounding association with our risk factors and PCL-S scores. Even with our robust follow-up at 3 and 12 months, some patients had missing history and outcomes data. Given that excluding such patients would bias our results, we used multiple imputation to account for missing data in our multivariable modeling per published recommendations (24).

The long-term consequences of ICU-related PTSD symptom clusters and PTSD diagnosis on quality of life, return to work, and societal reintegration remain unclear, as does the neurobiological basis for distinct prevention and treatment strategies in this population (52). Further epidemiologic work on ICU-related PTSD should strive to use the most current, reliable, and validated DSM-5–based screening and diagnostic tools as well as untangle the intertwined roles of preexisting psychiatric disorders and posthospitalization mental health recovery (54). Future ICU-related PTSD work may focus on expanded and novel ICU multidisciplinary interventions, such as ICU diary usage for prevention, pharmacologic prophylaxis for PTSD, psychological treatment, and combined cognitive with physical therapy (47, 55, 56), as well as conducting earlier in-hospital mental health screening and raising awareness of this disease among the individuals caring for ICU survivors.

Footnotes

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1158OC on January 6, 2016

Supported by the Veterans Affairs (VA) Clinical Science Research and Development Service (P.P.P., R.S.D., and E.W.E.); the VA Tennessee Valley Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (T.D.G., R.S.D., and E.W.E.); the Vanderbilt Faculty Research Scholars Program (M.B.P.); National Institutes of Health grants UL1TR000445 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/Clinical and Translational Science Award), AG027472 and HL111111 (P.P.P., C.G.H., R.S.D., and E.W.E.), AG035117 (P.P.P., R.S.D., and E.W.E.), AG034257 (T.D.G.), and AG031322 (J.C.J.); and a Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research Mentored Research Training Grant (C.G.H.). None of the study sponsors had any role in study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication. The researchers are independent from sponsors.

Author Contributions: M.B.P., J.L.T., and R.C. analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted and critically revised the article. J.C.J., E.W.E., R.S.D., and P.P.P. designed and implemented the cohort and acquired data (Nashville), analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted and critically revised the article. A.M. and A.L.K. acquired and interpreted the data and drafted and critically revised the article. T.D.G., C.G.H., and J.C.B. interpreted the data and drafted and critically revised the article. M.R.E., M.L.W., and R.B.G. designed and implemented the cohort and acquired data (Seattle and Salt Lake City), interpreted the data, and drafted and critically revised the article. All authors approved the final version for submission and publication. All authors have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Stevens RD, Sharshar T, Ely EW. Brain disorders in critical illness. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peitz GJ, Balas MC, Olsen KM, Pun BT, Ely EW. Top 10 myths regarding sedation and delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:S46–S56. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a168f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wade DM, Brewin CR, Howell DCJ, White E, Mythen MG, Weinman JA. Intrusive memories of hallucinations and delusions in traumatized intensive care patients: an interview study. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20:613–631. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M, Flaatten H, Rylander C, Griffiths RD. Precipitants of post-traumatic stress disorder following intensive care: a hypothesis generating study of diversity in care. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:978–985. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0600-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M, Egerod I, Flaatten H, Granja C, Rylander C, Griffiths RD RACHEL group. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R168. doi: 10.1186/cc9260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, Young JD. The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1506–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothenhäusler H-B, Grieser B, Nollert G, Reichart B, Schelling G, Kapfhammer H-P. Psychiatric and psychosocial outcome of cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a prospective 12-month follow-up study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schelling G, Richter M, Roozendaal B, Rothenhäusler H-B, Krauseneck T, Stoll C, Nollert G, Schmidt M, Kapfhammer H-P. Exposure to high stress in the intensive care unit may have negative effects on health-related quality-of-life outcomes after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1971–1980. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069512.10544.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, Hopkins RO, Girard TD, Ely EW. Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms following critical illness in medical intensive care unit patients: assessing the magnitude of the problem. Crit Care. 2007;11:R27. doi: 10.1186/cc5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wade D, Hardy R, Howell D, Mythen M. Identifying clinical and acute psychological risk factors for PTSD after critical care: a systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79:944–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Brummel NE, Thompson JL, Hughes CG, Pun BT, Vasilevskis EE, Morandi A, Shintani AK, et al. Bringing to light the Risk Factors And Incidence of Neuropsychological dysfunction in ICU survivors (BRAIN-ICU) study investigators. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369–379. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel M, Jackson J, Morandi A, Girard T, Hughes C, Kiehl A, Thompson J, Chandrasekhar R, Ely E, Pandharipande P. Post-traumatic stress disorder prevalence and subtypes among survivors of critical illness. Crit Care. 2015;19:555. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel MB, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Girard TD, Hughes CG, Kiehl AL, Thompson JL, Chandrasekhar R, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP. PTSD prevalence and risk factors among veteran and non-veteran survivors of critical illness. Presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the Association of VA Surgeons 2015 Meeting. May 3, 2015, Miami, FL. Abstract QS15.

- 16.Patel MB, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Girard TD, Thompson JL, Chandrasekhar R, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP. PTSD prevalence and risk factors among veteran and non-veteran survivors of critical illness. Presented at the 5th Annual American Delirium Society Meeting. June 2, 2015, Baltimore, MD. Session XII, B.

- 17.Patel MB. PTSD prevalence, symptom clusters, and risk factors among veterans and non-veteran survivors of critical illness. Presented at the Southern Society of Clinical Surgery. March 24, 2015, Nashville, TN.

- 18.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK, et al. BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, Norman SB. Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:596–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald SD, Calhoun PS. The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD checklist: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peirce JM, Burke CK, Stoller KB, Neufeld KJ, Brooner RK. Assessing traumatic event exposure: comparing the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:210–218. doi: 10.1037/a0015578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groenwold RHH, Donders ART, Roes KCB, Harrell FE, Jr, Moons KGM. Dealing with missing outcome data in randomized trials and observational studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:210–217. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuelson KAM, Lundberg D, Fridlund B. Stressful memories and psychological distress in adult mechanically ventilated intensive care patients: a 2-month follow-up study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrins J, King N, Collings J. Assessment of long-term psychological well-being following intensive care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1998;14:108–116. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(98)80351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schelling G, Stoll C, Kapfhammer H-P, Rothenhäusler H-B, Krauseneck T, Durst K, Haller M, Briegel J. The effect of stress doses of hydrocortisone during septic shock on posttraumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life in survivors. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2678–2683. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199912000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schelling G, Briegel J, Roozendaal B, Stoll C, Rothenhäusler H-B, Kapfhammer H-P. The effect of stress doses of hydrocortisone during septic shock on posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:978–985. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scragg P, Jones A, Fauvel N. Psychological problems following ICU treatment. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:9–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kress JP, Gehlbach B, Lacy M, Pliskin N, Pohlman AS, Hall JB. The long-term psychological effects of daily sedative interruption on critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1457–1461. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-455OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rattray JE, Johnston M, Wildsmith JAW. Predictors of emotional outcomes of intensive care. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bienvenu OJ, Gellar J, Althouse BM, Colantuoni E, Sricharoenchai T, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Dennison CR, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year prospective longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2013;43:2657–2671. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davydow DS, Katon WJ, Zatzick DF. Psychiatric morbidity and functional impairments in survivors of burns, traumatic injuries, and ICU stays for other critical illnesses: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21:531–538. doi: 10.3109/09540260903343877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schelling G, Kapfhammer H-P. Surviving the ICU does not mean that the war is over. Chest. 2013;144:1–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harpaz-Rotem I, Tsai J, Pietrzak RH, Hoff R. The dimensional structure of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in 323,903 U.S. veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;49:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Girard TD, Shintani AK, Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Pun BT, Henderson MS, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms following critical illness requiring mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R28. doi: 10.1186/cc5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wade DM, Howell DC, Weinman JA, Hardy RJ, Mythen MG, Brewin CR, Borja-Boluda S, Matejowsky CF, Raine RA. Investigating risk factors for psychological morbidity three months after intensive care: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R192. doi: 10.1186/cc11677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schelling G, Roozendaal B, Krauseneck T, Schmoelz M, DE Quervain D, Briegel J. Efficacy of hydrocortisone in preventing posttraumatic stress disorder following critical illness and major surgery. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:46–53. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauer D, Weis F, Krauseneck T, Vogeser M, Schelling G, Roozendaal B. Traumatic memories, post-traumatic stress disorder and serum cortisol levels in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Brain Res. 2009;1293:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davydow DS, Kohen R, Hough CL, Tracy JH, Zatzick D, Katon WJ. A pilot investigation of the association of genetic polymorphisms regulating corticotrophin-releasing hormone with posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in medical-surgical intensive care unit survivors. J Crit Care. 2014;29:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bienvenu OJ, Neufeld KJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder in medical settings: focus on the critically ill. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0166-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Berg DPG, de Bont PAJM, van der Vleugel BM, de Roos C, de Jongh A, Van Minnen A, van der Gaag M. Prolonged exposure vs eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs waiting list for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with a psychotic disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:259–267. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pietrzak RH, Gallezot J-D, Ding Y-S, Henry S, Potenza MN, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Carson RE, Neumeister A. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with reduced in vivo norepinephrine transporter availability in the locus coeruleus. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1199–1205. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Han C, Pae C-U, Wang S-M, Lee S-J, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Serretti A. The potential role of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;56:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.PTSD care, out of service. Lancet. 2014;383:2186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Efforts in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations: final assessment. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Tøien K, Karlsson S, Stokland O. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression symptoms in patients during the first year post intensive care unit discharge. Crit Care. 2010;14:R14. doi: 10.1186/cc8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, Skirrow PM. Memory, delusions, and the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:573–580. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Granja C, Amaro A, Dias C, Costa-Pereira A. Outcome of ICU survivors: a comprehensive review. The role of patient-reported outcome studies. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:1092–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hauer D, Kaufmann I, Strewe C, Briegel I, Campolongo P, Schelling G. The role of glucocorticoids, catecholamines and endocannabinoids in the development of traumatic memories and posttraumatic stress symptoms in survivors of critical illness. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2014;112:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friedman MJ. Risk factors for suicides among army personnel. JAMA. 2015;313:1154–1155. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:642–653. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ullman AJ, Aitken LM, Rattray J, Kenardy J, Le Brocque R, MacGillivray S, Hull AM. Intensive care diaries to promote recovery for patients and families after critical illness: a Cochrane Systematic Review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MACE. CE: critical care recovery center: an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs. 2015;115:24–31. [Quiz pp. 34, 46]. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000461807.42226.3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]