Abstract

Rationale: Adverse effects of exposures to ambient air pollution on lung function are well documented, but evidence in racial/ethnic minority children is lacking.

Objectives: To assess the relationship between air pollution and lung function in minority children with asthma and possible modification by global genetic ancestry.

Methods: The study population consisted of 1,449 Latino and 519 African American children with asthma from five different geographical regions in the mainland United States and Puerto Rico. We examined five pollutants (particulate matter ≤10 μm and ≤2.5 μm in diameter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide), derived from participant residential history and ambient air monitoring data, and assessed over several time windows. We fit generalized additive models for associations between pollutant exposures and lung function parameters and tested for interaction terms between exposures and genetic ancestry.

Measurements and Main Results: A 5 μg/m3 increase in average lifetime particulate matter less than or equal to 2.5 μm in diameter exposure was associated with a 7.7% decrease in FEV1 (95% confidence interval = −11.8 to −3.5%) in the overall study population. Global genetic ancestry did not appear to significantly modify these associations, but percent African ancestry was a significant predictor of lung function.

Conclusions: Early-life particulate exposures were associated with reduced lung function in Latino and African American children with asthma. This is the first study to report an association between exposure to particulates and reduced lung function in minority children in which racial/ethnic status was measured by ancestry-informative markers.

Keywords: air pollution, minority, children, lung function, ancestry

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Air pollution has been associated with adverse respiratory health effects, including reduced lung function. Few studies, however, have examined possible effects in minority populations, which may be more susceptible to adverse health outcomes owing to genetic susceptibility and/or increased social vulnerability.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We found associations between exposures to particulate matter and reduced lung function in Latino and African American children with asthma from different geographical regions in the United States. Our results suggest geographical heterogeneity of short-term effects of exposures to particulate matter and potential differences in early-lifetime exposure effects in children from different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Ambient air pollution has been consistently linked to respiratory outcomes (1–3), including risk of asthma (4, 5), asthma-related hospitalizations (6–8), poor asthma control (9, 10), overall lung function impairment (11, 12), and reduced response to bronchodilator medications (13), with many of these associations observed in pediatric populations. A recent study in Southern California communities found that long-term improvement in air quality was associated with positive effects on lung function growth in children from three different cohorts spanning three different time periods (14). This was an important finding concerning continuous improvement of air quality; although early life lung development and lung function growth do not necessarily manifest as immediate clinical events, they may still be predictive of future chronic disease (15).

Few studies, however, have focused their examination on air pollution effects in vulnerable populations, such as minority children. Minority populations are at higher risk of developing asthma and having more severe asthma relative to the general population (16). Potential reasons include reduced access and responsiveness to medication and other socioeconomic factors (17, 18). Regional variation in air pollution composition may also be an important factor leading to heterogeneous health effects (19). This can have important health implications, as minority populations are more likely to live in more polluted areas compared with white populations (20). Some of the limited literature on air pollution effects in minority children suggests that air pollution is associated with worse asthma symptoms and poorer lung function in minorities with asthma (21, 22). We have previously reported that early-lifetime exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is associated with increased risk of childhood asthma in Latinos and African Americans, with potentially greater risk in African Americans compared with Mexican Americans (4). In addition, we have shown that genetic African ancestry is associated with increased risk of asthma in Latino children, whereas, conversely, Native American ancestry was associated with lower odds of asthma, and that African ancestry was associated with reduced lung function among children with asthma (23). Furthermore, alleles protective for the risk of asthma have been found to be more common in Native American populations, and, among Latinos, have been found in greater frequency among Mexican populations compared with other Latinos (23–25). Specific gene variants have also been linked to increased susceptibility of asthma in the presence of air pollution (26–28). These findings suggest the possibility of population-specific responses to ambient air pollution and possible modification of air pollution effects by genetic ancestry. However, substantive evidence on how air pollution may have different effects in different minority groups remains scarce.

In the current study, we aimed to assess the effect of air pollution on overall lung function in a population consisting of African American and Latino children and adolescents from different geographical regions, and whether these associations are modified by genetic ancestry within this study population.

Methods

Study Population

The GALA II (Genes–Environments and Admixture in Latino Americans) study and the SAGE II (Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes, and Environments) are described in detail elsewhere (4). Briefly, they are parallel case–control studies representing the largest gene–environment study of asthma in minority children in the United States. GALA II recruited Latinos from five regions (Chicago, IL; Bronx, NY; Houston, TX; San Francisco Bay Area, CA; and Puerto Rico) and SAGE II recruited African Americans from the San Francisco Bay Area only. Participants in the two studies were 8–21 years old, had no history of other lung or chronic diseases, were self-identified Latino or African American, and had four Latino or African American grandparents, respectively. Asthma cases were defined as subjects with a physician diagnosis of asthma, plus two or more symptoms of coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath in the past 2 years. Subjects in the third trimester of pregnancy, current smokers, or those with at least 10 pack-years smoking history were excluded.

In the current study, analyses were restricted to the asthma cases from GALA II and SAGE II. The final sample size consisted of 1,968 subjects, with complete data on age, sex, height, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), current secondhand smoke exposure, and successful quality control measures for genotyping and spirometry.

Outcome Assessment and Covariates

We performed spirometry using KoKo PFT Spirometers (nSpire Health Inc., Louisville, CO) according to American Thoracic Society criteria (29). Participants were asked not to use their bronchodilator medication 8 hours before spirometry testing. We obtained up to eight tracings to collect five reproducible flow–volume loops with less than 5% variability in FEV1 (in liters). For analysis, we extracted the loop with the best performance. We evaluated three raw lung function metrics: FEV1, FVC (L), and forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity (FEF25–75, L/s).

We recorded information on age, sex, and height. Demographic information, medical histories, environmental exposures, and residential histories were obtained through questionnaires administered by trained bilingual (English–Spanish) interviewers. We created a composite SES variable as a function of annual household income, maternal level of education, and insurance type (18).

We evaluated genetic ancestry using methods described elsewhere (24). Briefly, we calculated the proportion of genetic ancestry by first genotyping all subjects with the Axiom LAT1 array (World Array 4; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) (30). We then obtained estimates of global genetic ancestry using an unsupervised analysis in ADMIXTURE (31) to determine the proportions of African, European, and Native American ancestry for Latinos, and the proportions of African and European ancestry for African Americans.

Exposure Assessment

We assigned each participant’s residence geographic coordinates using the TomTom/Tele Atlas EZ-Locate software (TomTom, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). We obtained regional ambient daily air pollution data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality System. To estimate pollution values for the participant’s residential geographic coordinate, we calculated the inverse distance-squared weighted average from the four closest air pollution monitoring stations within 50 km of the residence (4). In the case of Puerto Rico, pollution data were available from only two stations. We estimated daily average exposures for the day of spirometry testing (Lag 0). We calculated average exposures for the week (7 d) and month (30 d) before spirometry testing by averaging all available daily exposures during that time period. We also estimated average yearly exposure to each of the pollutants at the reported residential address (or a time-weighted estimate based on the amount of months spent at each different address in a given year where applicable) using all available daily pollutant measures. Average lifetime exposures were in turn estimated using the yearly average estimates. Not all pollutants were measured every day, resulting in location- and pollutant-dependent missing values. We estimated pollution exposures for NO2, sulfur dioxide (SO2), ozone (8-h daily maximum), and particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter less than or equal to 2.5 μm (PM2.5) and less than or equal to 10 μm (PM10).

Statistical Analyses

We fit generalized additive linear models to assess associations between pollutant concentrations and lung function for each recruitment region. We fit separate models for FEV1, FVC, and FEF25–75 as the outcomes of interest and for different windows of exposure for each pollutant. We entered log-transformed values of lung function parameters in all models, and estimated effects as percent change in the outcome. We used: penalized splines to control for age, height, and calendar time (entered as a continuous term to control for possible seasonal effects), thus allowing for nonlinear effects; indicator variables for sex and race/ethnicity; and continuous variables for SES (composite score variable) and number of smokers in the household. All models included percent genetic African ancestry, which has been shown to be strongly associated with lower lung function (23, 32, 33). We generated summary effect estimates from the five regions using random-effects meta-analysis with a restricted maximum-likelihood estimator, and heterogeneity of effects was assessed using the I2 statistic. We reassessed statistical significance for summary effect estimates after a post hoc adjustment for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni adjusted P value at 0.002 accounting for 25 tests per outcome, 5 pollutants × 5 windows of exposure).

For pollutants showing associations with lung function, we assessed possible effect modification by global African and Native American ancestry in the GALA II subjects with interaction terms. We also assessed effect modification by sex, obesity, SES, atopy, and parental asthma. Sensitivity analyses included models using percent predicted FEV1 based on Global Lung Initiative reference equations (34) for pollutants showing significant associations in the primary analysis. We also examined for nonlinearity of effects through use of penalized spline terms for pollutant effects. All analyses were performed using R version 3.2.0 software (R core team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

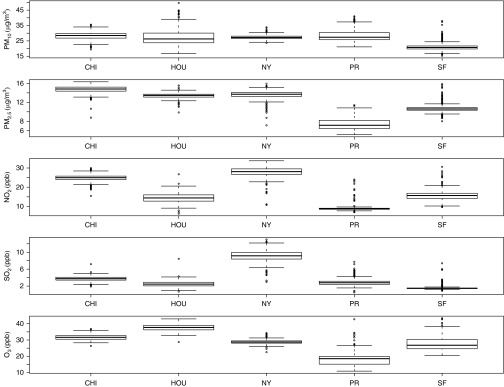

Analyses were performed on 1,968 children and adolescents with asthma from the GALA II (n = 1,449) and SAGE II (n = 519) studies. Demographic characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1, stratified by study. Briefly, the two studies were similar with respect to anthropometric variables as well as age and sex distribution. The average percent of African ancestry in SAGE II subjects was 79% with a range of 28–100%. Average percent African ancestry in GALA II subjects was 14% with a range of 0–85%, whereas the average percent Native American ancestry was 33% with a range of 1–100%. Ancestry estimates by self-reported ethnicity are summarized in Table 2. Boxplots of average lifetime air pollutant concentrations are summarized in Figure 1, and correlations among pollutant exposures are presented in Table 3. Air pollution concentrations for other exposure windows are summarized in Figures E1–E4 in the online supplement.

Table 1.

GALA II and SAGE II Cases (Combined N = 1,968) with Complete Demographic and Lung Function Characteristics

| Characteristics | GALA II (n = 1,449) | SAGE II (n = 519) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 12.6 ± 3.2 | 13.7 ± 3.5 |

| Male, n (%) | 818 (56.4) | 277 (53.4) |

| Height, cm, mean ± SD | 150.6 ± 14.0 | 157.0 ± 14.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 23.1 ± 6.4 | 24.5 ± 7.1 |

| SES,* mean ± SD | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 6.4 ± 1.4 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Puerto Rican | 655 (45.2) | — |

| Mexican | 506 (34.9) | — |

| Other Latino | 288 (19.9) | — |

| African American | — | 519 (100) |

| Region, n (%) | ||

| SF Bay Area | 266 (18.4) | 519 (100) |

| Puerto Rico | 560 (38.6) | — |

| Chicago | 259 (17.9) | — |

| New York | 184 (12.6) | — |

| Houston | 180 (12.4) | — |

| FEV1, L, mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| FVC, L, mean ± SD | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 0.9 |

| FEF25–75, L/s, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 1.0 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; FEF25–75 = forced expiratory flow between 25 and 75% of vital capacity; GALA II = Genes–Environments and Admixture in Latino Americans study; SAGE II = Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes, and Environments; SES = socioeconomic status; SF = San Francisco.

Composite socioeconomic index variable based on household income, maternal education level, and health insurance type, with a range of 3–9.

Table 2.

Percent African and Native American Ancestry* by Self-reported Ethnicity in the GALA II and SAGE II Cases

| Self-reported Ethnicity | % African Ancestry |

% Native American Ancestry |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| African American (SAGE II) | 78.9 (12.0) | 28.2–100.0 | — | — |

| Latino (GALA II) | ||||

| Mexican | 4.3 (3.0) | 0.0–36.0 | 55.4 (16.0) | 3.6–98.9 |

| Puerto Rican | 22.4 (11.7) | 5.1–73.2 | 10.4 (4.1) | 0.8–55.3 |

| Other Latino | 16.0 (15.2) | 0.0– 85.1 | 35.3 (23.7) | 1.0–100.0 |

Definition of abbreviations: GALA II = Genes–Environments and Admixture in Latino Americans study; SAGE II = Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes, and Environments.

Percent global ancestry in Latinos (GALA II) was assessed as the proportion of the sum of Native American, African, and European ancestry for each of the three ancestral populations, whereas in African Americans, it was assessed as the proportion of the sum of African and European ancestry for the two ancestral populations.

Figure 1.

Box plots of average lifetime pollutant concentrations stratified by recruitment region. CHI = Chicago; HOU = Houston; NY = New York; O3 = ozone; PM2.5 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM10 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm; PR = Puerto Rico; SF = San Francisco.

Table 3.

Pollutant Pearson Correlations for Same-Day 24-Hour Average Exposures, First Year of Life Average, and Lifetime Average Exposures

| Pollutant | PM10 | PM2.5 | NO2 | SO2 | O3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h average | |||||

| PM10 | — | 0.50* | 0.25* | 0.10* | 0.0 |

| PM2.5 | 0.50* | — | 0.35* | 0.16* | −0.01 |

| NO2 | 0.25* | 0.35* | — | 0.59* | −0.08* |

| SO2 | 0.10* | 0.16* | 0.59* | — | −0.08* |

| O3 (8-h max) | 0.0 | −0.01 | −0.08* | −0.08* | — |

| First year of life | |||||

| PM10 | — | 0.18* | 0.26* | 0.19* | 0.17* |

| PM2.5 | 0.18* | — | 0.81* | 0.39* | 0.19* |

| NO2 | 0.26* | 0.81* | — | 0.51* | 0.02 |

| SO2 | 0.19* | 0.39* | 0.51* | — | 0.15* |

| O3 | 0.17* | 0.19* | 0.02 | 0.15* | — |

| Average lifetime | |||||

| PM10 | — | 0.03† | 0.21* | 0.40* | −0.11* |

| PM2.5 | 0.03† | — | 0.84* | 0.39* | 0.73* |

| NO2 | 0.21* | 0.84* | — | 0.63* | 0.49* |

| SO2 | 0.40* | 0.39* | 0.63* | — | 0.04† |

| O3 | −0.11* | 0.73* | 0.49* | 0.04† | — |

Definition of abbreviations: O3 = ozone; PM2.5 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM10 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm.

Denotes statistically significant correlation (P < 0.001 for the test of null hypothesis that the correlation is 0).

Denotes statistically significant correlation (P < 0.05 for the test of null hypothesis that the correlation is 0).

Lifetime Average Exposures

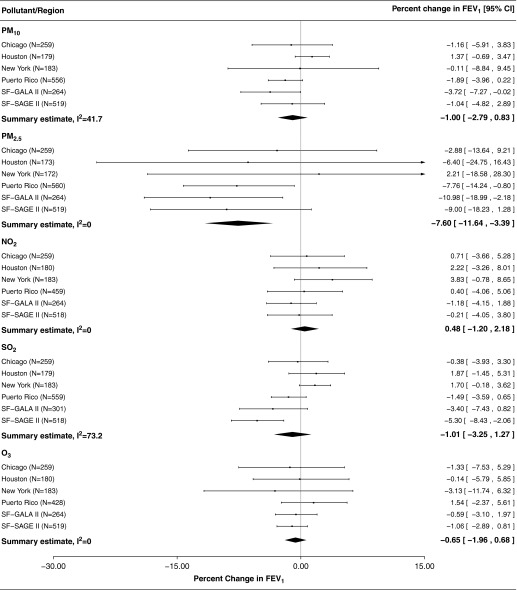

Forest plots for the associations between FEV1 and lifetime average exposure for each of the pollutants are presented in Figure 2. Average lifetime exposures to PM2.5 were associated with FEV1, with a 7.7% decrease (95% confidence interval [CI] = −11.8 to −3.5%) in FEV1 associated with each 5 μg/m3 increase in exposure when effect estimates were combined from all regions. No other pollutant yielded a significant association when exposure was averaged over the lifetime. Results for the associations between average lifetime PM2.5 and FEF25–75 were even greater in magnitude compared with FEV1, with a 13.8% decrease in FEF25–75 (95% CI = −20.9 to −6.0%) for each 5 μg/m3 increase in exposure. Although not statistically significant, the same trend was seen in the relationship between average lifetime exposure to PM2.5 and FVC (5.2% decrease in FVC [95% CI = −11.8 to 2.0%] per 5 μg/m3 increase in average lifetime PM2.5). P values for summary effect estimates for the association between lifetime PM2.5 and FEV1 (P = 0.0005) and FEF25–75 (P = 0.0008) were below the adjusted level for multiple comparisons. In the sensitivity analysis using percent predicted values for FEV1 based on Global Lung Initiative reference equations, results were qualitatively similar with a 4.5 decrease in percent predicted FEV1 (95% CI = −8.6 to −0.4%) associated with each 5 μg/m3.

Figure 2.

Forest plots for percent change in FEV1 associated with each 5 unit (μg/m3/ppb; results for SO2 presented for 1 ppb increases) increase in pollutant concentrations averaged over the lifetime. Sample sizes (N) for each association varied depending on availability of data by pollutant and exposure window in question. CI = confidence interval; GALA II = Genes–Environments and Admixture in Latino Americans study; O3 = ozone; PM2.5 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM10 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm; SAGE II = Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes, and Environments; SF = San Francisco.

First Year of Life Average Exposures

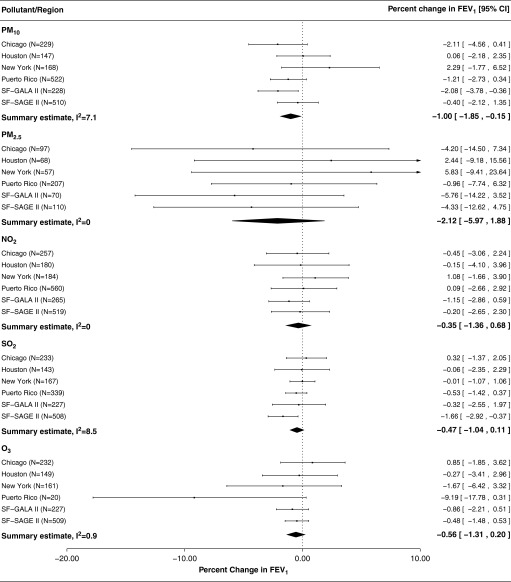

When looking at combined effect estimates from all regions, we observed a modest association between first year of life average exposure to PM10, with a 1.0% decrease in FEV1 (95% CI = −1.85 to −0.15%) associated with a 5 μg/m3 increase in exposure. We observed only suggestive associations for ozone and SO2 (Figure 3). The combined summary estimate for first year of life average exposures to PM2.5 was larger in magnitude than other pollutants, but was based on smaller sample sizes and was imprecise. Summary associations for the first year of life exposure did not meet the multiple comparisons adjusted level of significance for any of the pollutants. In region-specific analyses, the association for first year of life average exposure to PM10 and FEV1 was stronger in GALA II compared with SAGE II in the San Francisco Bay Area, whereas the opposite was true for first year of life average exposures to SO2.

Figure 3.

Forest plots for percent change in FEV1 associated with each 5 unit (μg/m3/ppb; results for SO2 presented for 1 ppb increases) increase in first year of life average pollutant concentrations. Sample sizes (N) for each association varied depending on availability of data by pollutant and exposure window in question. CI = confidence interval; GALA II = Genes–Environments and Admixture in Latino Americans study; O3 = ozone; PM2.5 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; PM10 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm; SAGE II = Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes, and Environments; SF = San Francisco.

Same-Day (Lag 0) 24-Hour Average Exposures

When all regions were combined, none of the summary estimates was statistically significant in the case of same-day 24-hour average exposure (Lag 0) to any of the pollutants (Figure E5). We observed the strongest association between same-day exposures and FEV1 in the case of PM10, but effects across regions were heterogeneous (I2 = 84%, P value for test of heterogeneity = 0.001). Analyses using spline terms for pollutant concentrations also yielded significant terms only for the San Francisco Bay Area and Puerto Rico regions, and effects in these regions appeared to be linear (Figure E6).

Other Time Windows and Interactions

Average weekly pollutant exposures were not strongly associated with FEV1, whereas suggestive associations were observed for average monthly exposures to particulates, but not for other pollutants (Figures E7 and E8).

Although African genetic ancestry was associated with lower lung function, inclusion of interaction terms in lung function models between pollutant exposures and global genetic ancestry did not improve model fit, nor did it result in any statistically significant interactions between pollutants and genetic ancestry as continuous variables (Table 4). In models for Puerto Rico, the change in FEV1 associated with an average lifetime PM2.5 exposure and percent Native American ancestry interaction was a 2.5% increase (95% CI = −1.1 to 6.2) for a 5 μg/m3 increase in exposure and a 10% increase in Native American ancestry. The corresponding numbers for exposure and percent African ancestry interaction represented a 0.4% decrease (95% CI = −5.8 to 5.2).

Table 4.

Estimates for Pollutant and Genetic Ancestry Interaction Terms in GALA II Subjects in the San Francisco Bay Area and Puerto Rico, Corresponding to a 5 μg/m3 Increase in Exposure and 10% Increase in Ancestry*

| % African Ancestry |

% Native American Ancestry |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change in FEV1 (95% CI) | P Value of Log Likelihood Test† | % Change in FEV1 (95% CI) | P Value of Log Likelihood Test† | |

| SF Bay Area | ||||

| Ancestry × average lifetime PM2.5 | −16.5 (−29.9 to 19.1) | 0.15 | −0.1 (−0.6 to 0.4) | 0.26 |

| Puerto Rico | ||||

| Ancestry × average lifetime PM2.5 | −0.4 (−5.8 to 5.2) | 0.76 | 2.5 (−1.1 to 6.2) | 0.12 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; GALA II = Genes–Environments and Admixture in Latino Americans study; PM2.5 = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm; SF = San Francisco.

Exposure and % ancestry modeled as continuous variables.

P value for the log likelihood test comparing model with main effect and interaction terms to model with main effect terms only. Null hypothesis is that interaction term does not improve model fit.

Assessment of potential effect modification of the effect of average lifetime PM2.5 exposures on lung function by additional variables considered did not yield any significant findings. Associations between FEV1 and the exposure were very similar between strata of the potential modifiers (Table E1).

Discussion

We observed associations between reduced lung function and average lifetime exposure to PM2.5 in Latino and African American youth with asthma from different regions in the United States and Puerto Rico. We observed suggestive associations with 24-hour and early-lifetime exposure to PM10 and reduced lung function. We did not observe a significant modifying effect by global genetic ancestry, or other variables. Our results indicate that particulate exposures are associated with reduced lung function in these minority populations.

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine the effects of air pollution on lung function and for possible modification by genetic ancestry in minority populations, which may be especially susceptible. We examined for possible air pollution effects on lung function across different regions controlling for genetic ancestry and self-reported race/ethnicity and assessed possible interactions with global genetic ancestry.

Global genetic ancestry did not appear to be a significant modifier of overall associations within Latinos in the same geographical region. This does not necessarily indicate that genetics should not be considered when assessing air pollution effects in minority children with asthma. Global ancestry measures the proportion of the genome inherited from one or more parental populations within an admixed individual (30, 31), and although they correlate highly with self-reported race/ethnicity, there is evidence that self-reported race is likely to leave a portion of the substructure within admixed populations, as race/ethnicity are sociopolitical constructs, the categories of which are fluid and subject to change along with societal and cultural trends (33, 35–37). Recent studies have shown that genetic ancestry was associated with pulmonary traits (asthma prevalence/severity, lung function) independent of self-reported race in African Americans and Puerto Ricans (23, 32, 33, 38). Therefore, to avoid potential confounding, it is important to consider both self-identified race/ethnicity and genetic ancestry when constructing statistical models to assess the relationship between lung function and exposures of interest in admixed populations, such as the population of interest in the present study.

As potential effect-modifying variables, measures of global ancestry are most powerful in situations in which a large number of genetic variants, with small effect sizes, preferentially inherited from a specific ancestral population(s), act in tandem to modify the relationship between phenotype and predictor. However, in cases where a small number of specific loci, with modest to large effects, derived preferentially from one ancestral group in an admixed individual, global ancestry proportions may be too crude of a measurement to detect these modifying effects, as their relatively small number would not greatly affect the overall proportion of the ancestral group from which they originated. Any ancestry modifying effects in our study may be too subtle to be captured by global genetic ancestry measurement; local genetic ancestry may be better suited to identify ancestry–air pollution interactions with respect to lung function in these minority populations. In addition, the current study was underpowered to detect significant interaction effects of small magnitudes in recruitment region–specific analyses.

We saw no significant associations for short-term PM2.5 exposures, but average lifetime exposures to PM2.5 appeared predictive of lung function, suggesting a potentially longer-term effect. Previous studies linking early-life particulate exposures to lung function report associations between fine particulate (PM2.5) exposures and chronic effects on lung function, as well as reductions in air pollution associated with improved lung development over time in children in Southern California (14, 39). Our findings for lifetime exposure to PM2.5 are consistent with these reports. Sensitivity analysis by Gauderman and colleagues (14) indicated that improvement in lung function growth associated with lower air pollution over time was greater in children with asthma compared with children without asthma, indicating potentially increased susceptibility. Decreased lung function associated with air pollution has also been reported in studies of children in Europe (40, 41). Previous studies have also reported associations between reduced lung function and exposures to NO2 (14, 40), but we only observed significant associations for particulate exposures.

Limitations of this study included missing air pollution data, particularly with respect to same-day exposures to PM10 and early-lifetime exposures to PM2.5. Analyses for different pollutants and different time windows of exposure were based on different sample sizes depending on availability of exposure data. PM10 was only sampled once every 6 days in the San Francisco Bay Area, and once every 3 days in Puerto Rico during the recruitment period, as opposed to other region and pollutant combinations. In addition, data on early-lifetime exposures to PM2.5 were limited, as some of the participants were born before PM2.5 was required to be systematically sampled by the Environmental Protection Agency in all locations. Air pollution data in Puerto Rico relied on only two monitoring stations; therefore, exposure misclassification is more likely in subjects from this region. Nondifferential misclassification of exposures for many subjects is likely, as no personal air pollution measurements were available, but any potential bias due to this misclassification is expected to be toward the null (42). Information on indoor air pollution levels was lacking. The use of residential addresses to determine exposures, however, is a strength compared with studies using community-level data. Given the varying regional distribution of the different racial/ethnic groups considered in this study, heterogeneity of effects is difficult to interpret. Effect modifiers, other than race and ethnicity, may also vary by region; however, stratification by race/ethnicity in all recruitment regions was not possible.

The cross-sectional nature of the comparisons considered in this study limits our ability to infer causality for observed associations, as they only represent a snapshot of the study population. The availability of extensive data on covariates on the individual level, such as socioeconomic factors that may be predictive of health disparities in minority populations, is, however, a considerable strength. Other strengths of this study include the minority populations, relatively large sample size for lung function as an outcome, individual exposure estimates, as well as the availability of genetic ancestry measurements in addition to self-reported race/ethnicity. Observed associations of spirometry and pollutant exposures were greater in magnitude for FEF25–75 as the outcome of interest; FEF25–75 has been shown in recent studies to be a highly sensitive marker of airway obstruction, and may be a more informative lung function parameter than FEV1 in children with asthma (43, 44). Results were also robust in sensitivity analysis using percent predicted FEV1 based on Global Lung Initiative reference equations. These predictions are subject to misclassification, however, as they do not take into account genetic ancestry (33, 34).

In conclusion, findings from the current study suggest that lifetime particulate exposures are associated with reduced lung function in minority youth with asthma in the United States and Puerto Rico. Future work using a more detailed exposure assessment, local chromosomal ancestry, specific alleles, and epigenetic traits may provide further insight into the biological and environmental factors underlying the heterogeneity of air pollution effects on lung function, as well as overall asthma prevalence and severity.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the participants and families of the GALA II and SAGE II studies and thank the numerous health care providers and community clinics for their support and participation. In particular, the authors thank the study coordinator, Sandra Salazar, and the recruiters who obtained the data: Duanny Alva, M.D., Gaby Ayala-Rodriguez, Ulysses Burley, Lisa Caine, Elizabeth Castellanos, Jaime Colon, Denise DeJesus, Iliana Flexas, Blanca Lopez, Brenda Lopez, M.D., Louis Martos, Vivian Medina, Juana Olivo, Mario Peralta, Esther Pomares, M.D., Jihan Quraishi, Johanna Rodriguez, Shahdad Saeedi, Dean Soto, Ana Taveras, and Emmanuel Viera.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01-ES015794, U19-AI077439, R01-HL088133, R01-HL078885, R25-CA113710, T32-GM007546, R01-HL004464, and R01-HL104608 R21 ES024844 (E.G.B.), K23-HL093023 (R.K.), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under award P60MD006902 (K.B.-D. and E.G.B.), M01-RR00188 to the Texas Children’s Hospital General Clinical Research Center, Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, R.W.J.F. Amos Medical Faculty Development Award, the Sandler Foundation (E.G.B.), the American Asthma Foundation (L.K.W. and E.G.B.); C.R.G. was supported in part by the University of California, San Francisco Chancellor’s Research Fellowship, Dissertation Year Fellowship, and NIH Training Grant T32 GM007175; J.M.G. was supported in part by NIH Training Grant T32 GM007546 and career development awards from the NHLBI (K23HL111636) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR000143), as well as the Hewett Fellowship; M.P.-Y. was funded by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from Fundación Ramón Areces (www.fundacionareces.es).

Author Contributions: A.M.N. was responsible for data analyses and manuscript preparation with input from M.J.W., S.S.O., N.T., J.M.G., K.K.N., F.L., M.P.-Y., E.A.E., J.R.B., and E.G.B. E.A.N. cleaned and recoded all residential history addresses. F.L. calculated all pollution measurements and contributed to the interpretation of these measurements. H.J.F., D.S., R.K., E.B.-B., A.D., M.A.L., K.M., W.R.-C., P.C.A., S.M.T., J.R.R.-S., and E.G.B. planned and supervised the collection of data from the various recruitment regions in the initial cohort. All coauthors contributed to interpretation of results, provided revisions, and approved the final manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1706OC on January 6, 2016

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Dockery DW. Health effects of particulate air pollution. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dockery DW, Pope CAI., III Acute respiratory effects of particulate air pollution. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunekreef B, Holgate ST. Air pollution and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura KK, Galanter JM, Roth LA, Oh SS, Thakur N, Nguyen EA, Thyne S, Farber HJ, Serebrisky D, Kumar R, et al. Early-life air pollution and asthma risk in minority children: the GALA II and SAGE II studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:309–318. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0264OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383:1581–1592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope CA., III Respiratory disease associated with community air pollution and a steel mill, Utah Valley. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:623–628. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.5.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delamater PL, Finley AO, Banerjee S. An analysis of asthma hospitalizations, air pollution, and weather conditions in Los Angeles County, California. Sci Total Environ. 2012;425:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malig BJ, Green S, Basu R, Broadwin R. Coarse particles and respiratory emergency department visits in California. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:58–69. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Poon R, Chen L, Frescura A-M, Montuschi P, Ciabattoni G, Wheeler A, Dales R. Acute effects of air pollution on pulmonary function, airway inflammation, and oxidative stress in asthmatic children. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:668–674. doi: 10.1289/ehp11813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng Y-Y, Rull RP, Wilhelm M, Lombardi C, Balmes J, Ritz B. Outdoor air pollution and uncontrolled asthma in the San Joaquin Valley, California. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:142–147. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.083576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tager IB, Balmes J, Lurmann F, Ngo L, Alcorn S, Künzli N. Chronic exposure to ambient ozone and lung function in young adults. Epidemiology. 2005;16:751–759. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000183166.68809.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barraza-Villarreal A, Sunyer J, Hernandez-Cadena L, Escamilla-Nuñez MC, Sienra-Monge JJ, Ramírez-Aguilar M, Cortez-Lugo M, Holguin F, Diaz-Sánchez D, Olin AC, et al. Air pollution, airway inflammation, and lung function in a cohort study of Mexico City schoolchildren. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:832–838. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández-Cadena L, Holguin F, Barraza-Villarreal A, Del Río-Navarro BE, Sienra-Monge JJ, Romieu I. Increased levels of outdoor air pollutants are associated with reduced bronchodilation in children with asthma. Chest. 2009;136:1529–1536. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauderman WJ, Urman R, Avol E, Berhane K, McConnell R, Rappaport E, Chang R, Lurmann F, Gilliland F. Association of improved air quality with lung development in children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:905–913. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dockery DW, Ware JH. Cleaner air, bigger lungs. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:970–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1415785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lara M, Akinbami L, Flores G, Morgenstern H. Heterogeneity of childhood asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican children bear a disproportionate burden. Pediatrics. 2006;117:43–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burchard EG, Oh SS, Foreman MG, Celedón JC. Moving toward true inclusion of racial/ethnic minorities in federally funded studies: a key step for achieving respiratory health equality in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:514–521. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1944PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thakur N, Oh SS, Nguyen EA, Martin M, Roth LA, Galanter J, Gignoux CR, Eng C, Davis A, Meade K, et al. Socioeconomic status and childhood asthma in urban minority youths: the GALA II and SAGE II studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1202–1209. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1016OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell ML, Dominici F, Ebisu K, Zeger SL, Samet JM. Spatial and temporal variation in PM(2.5) chemical composition in the United States for health effects studies. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:989–995. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mott L. The disproportionate impact of environmental health threats on children of color. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:33–35. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delfino RJ, Gong H, Jr, Linn WS, Pellizzari ED, Hu Y. Asthma symptoms in Hispanic children and daily ambient exposures to toxic and criteria air pollutants. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:647–656. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis TC, Robins TG, Dvonch JT, Keeler GJ, Yip FY, Mentz GB, Lin X, Parker EA, Israel BA, Gonzalez L, et al. Air pollution–associated changes in lung function among asthmatic children in Detroit. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1068–1075. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pino-Yanes M, Thakur N, Gignoux CR, Galanter JM, Roth LA, Eng C, Nishimura KK, Oh SS, Vora H, Huntsman S, et al. Genetic ancestry influences asthma susceptibility and lung function among Latinos. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galanter JM, Gignoux CR, Torgerson DG, Roth LA, Eng C, Oh SS, Nguyen EA, Drake KA, Huntsman S, Hu D, et al. Genome-wide association study and admixture mapping identify different asthma-associated loci in Latinos: the Genes–Environments & Admixture in Latino Americans study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hancock DB, Romieu I, Shi M, Sienra-Monge JJ, Wu H, Chiu GY, Li H, del Rio-Navarro BE, Willis-Owen SA, Weiss ST, et al. Genome-wide association study implicates chromosome 9q21.31 as a susceptibility locus for asthma in Mexican children PLoS Genet 20095e1000623[Published erratum appears in PLoS Genet 5(12).] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.London SJ. Gene–air pollution interactions in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:217–220. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-031AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerkhof M, Postma DS, Brunekreef B, Reijmerink NE, Wijga AH, de Jongste JC, Gehring U, Koppelman GH. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 genes influence susceptibility to adverse effects of traffic-related air pollution on childhood asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:690–697. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.119636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam T, Berhane K, McConnell R, Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Peters JM, Gilliland FD. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) P1, GSTM1, exercise, ozone and asthma incidence in school children. Thorax. 2009;64:197–202. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.099366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry, 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann TJ, Zhan Y, Kvale MN, Hesselson SE, Gollub J, Iribarren C, Lu Y, Mei G, Purdy MM, Quesenberry C, et al. Design and coverage of high throughput genotyping arrays optimized for individuals of East Asian, African American, and Latino race/ethnicity using imputation and a novel hybrid SNP selection algorithm. Genomics. 2011;98:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brehm JM, Acosta-Pérez E, Klei L, Roeder K, Barmada MM, Boutaoui N, Forno E, Cloutier MM, Datta S, Kelly R, et al. African ancestry and lung function in Puerto Rican children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1484–90.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar R, Seibold MA, Aldrich MC, Williams LK, Reiner AP, Colangelo L, Galanter J, Gignoux C, Hu D, Sen S, et al. Genetic ancestry in lung-function predictions. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:321–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Ip MSM, Zheng J, et al. ERS Global Lung Function Initiative. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziv E, John EM, Choudhry S, Kho J, Lorizio W, Perez-Stable EJ, Burchard EG. Genetic ancestry and risk factors for breast cancer among Latinas in the San Francisco Bay Area. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1878–1885. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriguez B, Kardia SLR, Zhu X, Brown A, Pankow JS, Province MA, Hunt SC, Boerwinkle E, et al. Genetic structure, self-identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case–control association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:268–275. doi: 10.1086/427888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burnett MS, Strain KJ, Lesnick TG, de Andrade M, Rocca WA, Maraganore DM. Reliability of self-reported ancestry among siblings: implications for genetic association studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:486–492. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menezes AM, Wehrmeister FC, Hartwig FP, Perez-Padilla R, Gigante DP, Barros FC, Oliveira IO, Ferreira GD, Horta BL. African ancestry, lung function and the effect of genetics. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1582–1589. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00112114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Gilliland F, Vora H, Thomas D, Berhane K, McConnel R, Kuenzli N, Lurmann F, Rappaport E, et al. The effect of air pollution on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:1057–1067. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gehring U, Gruzieva O, Agius RM, Beelen R, Custovic A, Cyrys J, Eeftens M, Flexeder C, Fuertes E, Heinrich J, et al. Air pollution exposure and lung function in children: the ESCAPE project. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:1357–1364. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oftedal B, Brunekreef B, Nystad W, Madsen C, Walker S-E, Nafstad P. Residential outdoor air pollution and lung function in schoolchildren. Epidemiology. 2008;19:129–137. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeger SL, Thomas D, Dominici F, Samet JM, Schwartz J, Dockery D, Cohen A. Exposure measurement error in time-series studies of air pollution: concepts and consequences. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:419–426. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lebecque P, Kiakulanda P, Coates AL. Spirometry in the asthmatic child: is FEF25–75 a more sensitive test than FEV1/FVC? Pediatr Pulmonol. 1993;16:19–22. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950160105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon MR, Chinchilli VM, Phillips BR, Sorkness CA, Lemanske RF, Szefler SJ, Taussig L, Bacharier LB, Morgan W Childhood Asthma Research and Education Network of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity and FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio in relation to clinical and physiological parameters in asthmatic children with normal FEV1 values. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:527–534.e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]